Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

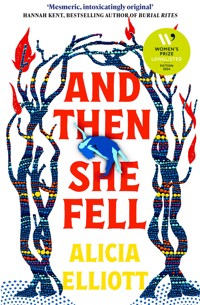

'Mesmeric, intoxicatingly original' Hannah Kent, bestselling author of Burial Rites 'Haunting and surreal... With its sharp wit and beautiful writing, this book had me flying through the pages.' Ana Reyes, New York Times bestselling author of The House in the Pines 'A towering achievement, stunningly good storytelling.' Melissa Lucashenko, Miles Franklin Award winning author of Too Much Lip On the surface, Alice is exactly where she should be in life: she's just given birth to a beautiful baby girl; her ever-charming husband - an academic whose area of study is conveniently her own Mohawk culture - is nothing but supportive; and they've moved into a home in a wealthy neighbourhood. But strange things have started happening. Alice finds herself hearing voices she can't explain and speaking with things that should not be talking back to her, all while her neighbours' passive aggression begins to morph into something far more threatening... Told in Alice's raw and darkly funny voice, and infused with Native American myth and legend, And Then She Fell is a wild, fierce novel.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 506

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Alicia Elliott is a Mohawk writer and editor living in Brantford, Ontario. Her short fiction was selected for Best American Short Stories 2018 and she won the 2018 RBC Taylor Emerging Writer Award. Her first book, A Mind Spread Out On The Ground, is a Canadian bestseller.

First published in the United States in 2023 by Dutton, an imprint ofPenguin Random House LLC.

Published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2023 byAllen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published by Atlantic Books in 2024.

Copyright © Alicia Elliott, 2023

The moral right of Alicia Elliott to be identified as the author of thiswork has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright,Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination.Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 942 5

Interior art: Night sky © Khaneeros T./Shutterstock.com;Feather © veronchick_84/Shutterstock.comBOOK DESIGN BY KRISTIN DEL ROSARIO

Allen & UnwinAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Missy and Melita,

and

For all thosewho have seen and heard what others can’t.

As evidence of the Western world’s fascination with the Iroquois, it is widely held that anthropology as an academic field of study began with Lewis Henry Morgan’s League of the Ho-De’-No-Sau-Nee, or Iroquois, published in 1851. While an overwhelming amount of scholarship has been devoted to the Haudenosaunee since that time . . . Haudenosaunee people have had very little opportunity to analyze our own history, culture, and traditions.

— RICK MONTURE,WE SHARE OUT MATTERS:TWO CENTURIES OF WRITING AND RESISTANCEAT SIX NATIONS OF THE GRAND RIVER

PROLOGUE

Around the Riverbend, Mostly

Alice never seemed to hear the microwave beeping— not even when she was three feet away from it, feet propped on the kitchen table as she painted her toenails neon green. It didn’t matter how loud or how insistent her ma was when she called her to dinner, either. She’d saunter into the kitchen whenever she felt like it, even if it meant her food was cold and congealed on her plate. At first, her aunt Rachel thought Alice’s hearing was to blame; she did sit alarmingly close to the speakers at pow-wows, after all, and her music pounded through her headphones so loud even the people she passed could hear each note. But a free hearing test confirmed her problem was not and had never been her ears. She could hear the microwave perfectly. She could hear everything perfectly.

Quite simply, Alice deliberately chose to ignore what she didn’t want to hear. Either the most teenage of all ailments, or the most human: for who wants to hear an incessant hammer banging down on one’s carefully constructed version of “real life”? Who wants to admit there was a moment when they saw disaster coming but chose to do nothing, only for the impending wave to crest and crash, forcing their carefully constructed version of “real life” to give way and collapse entirely?

This is probably why, despite the trail of girls Mason Jamieson left behind him like bread crumbs in the forest of masculinity— girls with mascara rippling down their teenage cheeks, with heartbreak and hatred now trapped in their very marrow— Alice still desperately wanted to follow that trail straight to him. What choice did she have? She was months away from becoming a faceless freshman, and he was once the coolest boy at J. C. Hill Elementary. There was something very chic about the idea of holding hands through the halls and getting pulled against his chest while he smoked, even if she knew from other girls that he repeated the most boring stories and his cigarette ash got caught in their hair. It might not be fulfilling, but it’d be validating, the way male attention could be. That was good enough. Probably.

Before this year Alice had been mostly ignored. She’d watched each of her friends fall victim to the onslaught of puberty: entering grade six with sweatshirts and pudgy cheeks and emerging from the other side with breasts and blackheads and skintight leggings that shouted every dimple to the world. Alice’s chest remained stubbornly flat, her hips defiantly narrow. When she walked down the street in a pair of shorts it was unremarkable. When her friends walked down the street in shorts it was an event. There were hoots and hollers from windows or porches, beeps from rusted-out rez cars, deep frowns from disapproving elders. There was something almost insidious about puberty— the way it slammed shut the door to childhood, never to be reopened, and shoved you face-first into this strange, dangerous place called womanhood.

But on the eve of her thirteenth birthday, puberty came for Alice, too. It molded her chest into tits, her butt into an ass, carved cheekbones out of her face. She tried to stifle her body with oversized shirts and poor posture, but it was no use. Those rebellious curves were still there, pushing out from the fabric, demanding their due. Both her ma and Aunt Rachel had tried to explain to Alice how her period connected her to our mother, the earth; our grandmother, the moon; how she was one in a line of women who could be traced all the way back to Sky Woman, the mother of our nations. They were trying to be nice, Alice knew, but it was too late. She saw the way men looked at her now. Women, too. As if she were land to claim, a rival to kill. She’d already resigned herself to the idea that her body was no longer hers: just flesh and bone on extended loan, bound to be collected by some man sooner or later. After that she would be his to own, his to decide what to do with, to sit on some pedestal or throw in some corner to cry.

That summer, Alice got a job selling 50/50 tickets at the speedway with her cousin Melita. She didn’t need a résumé. The boss, Helen, looked her up and down and told her she started Friday.

“Just dress sexy,” Helen said. Alice immediately summoned up the most beautiful woman she could think of: Jennifer-Lopez-as-Selena, in sequined jumpsuits and glitter bustiers, smiling with bright red lips.

“Um, I don’t think I have anything—”

“Trust me, we’ll make it work.”

And they did. Apparently, anything could be made sexy when you were a thirteen-year-old girl. Helen would roll up Alice’s shorts if they were too long, or strategically tie up her shirts to show off her flat stomach. She even kept an emergency stash of lip gloss at the concession stand so Alice could do touch-ups whenever dirt careened from the racetrack onto her sticky lips, temporarily ruining the underage bombshell fantasy with ugly, inconvenient reality. It smelled like cotton candy.

The customers, mostly older white men, would stare at her long tan limbs and smile at her like they knew something she didn’t. It bothered Alice, but the other 50/50 girls seemed resigned to it. Even adapted to it. They knew how to divide into two selves: the one that smiled sweetly to the men’s faces and laughed at their bad jokes, and the one that grimaced as soon as their backs were turned, collecting the interactions like baseball cards to trade with the other girls at the food stand. It became a game for them: the girls would share their encounters with these desperate old men, and at the end of the night whoever had the grossest story— the one that made the other girls groan and squirm with unease— was the girl who won.

Most of the time the stories were pretty tame. A wink here, a sudden unsolicited hand grab there. But one time a regular named Chuck followed Alice into the porta potty, rushing in before she could lock it, his body pushing hard against her backside. He was so close she could smell the damp of his deodorant, which barely covered the harsh stink of his old, sweating man body. She turned fast and looked up at him. His eyes were entirely black. He looked like he was possessed. Alice was too shocked to scream, to move. There was a long silence that stretched on, during which Alice could feel the walls of the porta potty vibrating with the race cars on the track. She closed her eyes, hoping that whatever came next would be quick.

Chuck laughed, the sharp honk of it forcing her watering eyes back open. “The look on your face!” he howled as he turned around and stumbled back to the stands.

Alice stayed in the porta potty until her breathing was normal again. She decided to hold her pee until she got home.

“What happened to you?” Melita asked her when she walked up, jittery. Alice told her.

“Ever gross! Oh my god, you gotta tell the girls. You’ll totally win tonight.”

“Should I tell Helen?”

“No point. As long as they’re spending money, she don’t care. Anyway, that’s the job, innit? Look cute so dirty old men buy tickets from us?”

Melita was right. That was the job. But after the races, after the eyes and the hands and “sweeties” and “dolls,” after Chuck and the porta potty, as she stared at the limp bills in her hand, she understood how little value they had. What’s more, she sensed that her own value was tied up in the whole transaction, only instead of watching it grow week by week like the small stash of bills she hid from her ma in her sock drawer, she felt it slowly diminishing, as if it were being pressed hard against a sieve.

Still, money was money, and Creator knows her mom didn’t have much to spare since her dad died in a car accident a couple years before. So Alice showed up promptly at seven every Friday night, shorts hiked up, lips smeared shiny and pink.

You’ll never guess who’s hanging around the food stand,” Melita said one night.

Alice was under the bleachers, tearing apart the strips of 50/50 tickets she and Melita had sold. The repetitive motion calmed her, so she offered to do it for her cousin, who was, it must be said, pretty lazy, at least when it came to work. Gossiping, on the other hand, Melita took very seriously. Alice stopped ripping tickets and looked at her cousin. Melita’s ears turned a red that rivaled her already blushed cheeks, the way they did when she knew something you didn’t.

“I don’t know. Nelly Furtado?”

“Don’t be stupid, Alice. What would a queen like that be doing in a place like this?”

“Watching the races?”

Melita ignored that and smiled. “Mason Jamieson,” she said, savoring the words as they rolled off her tongue, weighing the effect of every syllable.

Alice immediately felt light-headed. “No way. He’d never waste a Friday night here.”

“Go look for yourself.”

She peeked out from the bleachers and there he was, leaning against the food stand, smoking. Her breathing stopped as she croaked out two words: “Holy. Shit.”

Alice stared. She obviously remembered him— who wouldn’t?— puffing his chest on playgrounds and in parking lots, demanding and commanding eyes with every step of his nearly six-foot-tall frame. It’d been two years since he’d left J. C. Hill for Pauline Johnson Collegiate Vocational School. He was definitely taller now. His movements were smooth and confident, almost feline, as he lifted his cigarette to his lips. When she got older, she would realize how much of this was performance, how much was lifted from James Dean and early Marlon Brando movies, which, unbeknownst to all but his mother and sister, Mason studied fastidiously, even practicing the movements in front of the mirror, the way Alice herself practiced smiling in the perfect way to hide her snaggletooth. The self-consciousness that came with puberty pushed them both into odd shapes and awkward poses, but at thirteen, Alice didn’t notice the effort it took other people to look effortless, just her own, and so she only hated herself for it. Alice also had no way of knowing at the time that Mason’s stock had fallen considerably since he’d made the leap to high school, as happened with all Native kids once they stepped off the rez and into the mostly white high schools they were forced to attend in neighboring cities. Had she known all of this, it’s hard to say whether she would have proceeded in quite the way she did.

“He just broke up with Nancy, so I bet he’s looking for a new snag,” Melita said, needling.

“I don’t know . . . ,” she started.

“Well, I do. What are the odds your crush would end up here right after a breakup? It’s fate! You gotta go over there and ask him for a smoke. Now.” She grabbed Alice’s arm and dragged her toward the food stand. Alice tried to pry her fingers off, but it was no use. The Creator himself couldn’t stop Melita once her mind was made up.

“But I don’t smoke,” Alice whispered. “Or snag.”

Melita cackled. “You do now, honey.” She pushed Alice toward Mason, who was, thankfully, staring down at his black Razr phone. Alice managed to catch herself on a big blue metal garbage can before running into him, making a terrific clang in the process. Mason looked up, saw Alice, then took another drag of his cigarette.

“Hey,” he said.

“Hey,” Alice said, her throat raspy and dry. “Got a smoke?”

“I’m down to my last one.”

“Oh.”

“But we Hauds are trading people, innit?”

Alice looked down at her shoes, her heart racing. “What do you want for it?”

“That depends. You busy tomorrow night?”

Everything was happening so fast. Alice couldn’t think. Was she busy? Probably not. She was never busy. But she couldn’t tell Mason that.

“I could make time.” That sounded pretty cool. Like something the sort of girl Mason wanted to hang out with would say.

“Then this is yours.” He pulled out a pack of Sago Menthols and handed her his last cigarette. His hands were so big they looked like they could crush her head between them. Stop thinking and just be cool, Alice told herself as she placed it between her lips and pursed them expectantly. Mason produced a lighter and flicked the head ablaze. Luckily, Alice remembered Melita once told her the secret to faking smoking: don’t inhale.

“Put your number in here.” Mason handed over his cell phone. He was saving her number under the name “hot racetrack girl.” She debated typing her actual name in, but decided against it at the last minute. She didn’t want to look pushy.

“See you tomorrow,” he said as he took his phone and backed away, smiling at her. She watched him spin around and continue toward the bleachers. God, she thought. Even the way he walks is sexy.

Melita was beside her almost immediately.

“So? What happened?”

“We’re gonna hang out tomorrow night.”

“Are you KIDDING ME? You’re hanging out with Mason Jamieson tomorrow night? The girls are never gonna believe this.”

At that exact moment Alice remembered she’d agreed to babysit for her aunt Rachel.

“Fuck. I forgot. I’m babysitting Dana tomorrow.”

“I swear to fucking god, Al, if you throw away the chance to lose your virginity to Mason Jamieson for a babysitting gig I will kill you myself.”

“Do you really think we’ll have sex?”

“Of course! Guys like Mason basically need sex to live.”

Her friends had all lost their virginity by the time they graduated eighth grade—an event they felt compelled to share because tradition dictated they should, but which they described with little more than a shrug. It seemed to Alice that a woman’s virginity was a man’s trophy: they placed it on a shelf for all the other men to see, high-fiving one another as they celebrated how totally secure and super masculine they were. Women, on the other hand, threw their hymens to men like an old chicken bone to shut them up. There was nothing inherently valuable about virginity, or nothing she or her friends knew how to name. Having sex was just checking off another box, and at this point, Alice just wanted it over with. But the idea of losing her virginity at Aunt Rachel’s house kind of weirded her out. What was she supposed to do with Dana? Send her outside?

“Can you babysit for me?”

“No way! I’ve got a date with Corey. Anyway, isn’t Dana, like, five? Just put her to bed before he gets there.”

“Will that work?”

Melita shrugged.

Aunt Rachel’s house was small and cluttered and looked like a pow-wow vendor threw up on the walls. There were at least thirty dream catchers, twenty medicine wheels, and a dozen posters that read NATIVE PRIDE in a dozen different fonts. Seed beads of every color sat in plastic cups like hidden treasure around the house. Alice never knew when she’d step backward and knock a hundred tiny beads deep into the fibers of the carpet. It stressed her out.

But it was the one place where she felt like time hadn’t passed, might never pass. Her aunty and her little cousin’s love for her was eternal, unchanging. Her name even sounded different when they said it— precious, musical, like that one word was its own small ceremony. It sounded like that when Aunt Rachel was with Dana’s dad, even though her arms were bruised and her lips were swollen; it sounded like that when Aunt Rachel was pregnant and lived at Gano˛hkwásra, where she had to sign Alice and her ma in and out during visits, her eyes constantly trained on the door, as though Dana’s dad would barrel through at any moment; it sounded like that now, even though Alice’s period had started and wiry black hairs were sprouting everywhere faster than she could shave them. She needed that love without expectation. She needed it bad. Her ma had always referred to them as a “team”— which meant Alice was making dinner for herself by age nine, doing her and her ma’s laundry by age ten, and babysitting for extra cash by age eleven. And after her dad died, her mother expected her to pull more than her own weight. It was like she wasn’t allowed to be a kid at all anymore. Alice’s free time was always being judged, and so Alice herself was being judged. Strangely, she could feel the strain of her mother’s expectations even more strongly when she wasn’t around. But Aunt Rachel never judged her, never would.

That night, Alice and Dana were watching Pocahontas for what felt like the fiftieth time that month. Alice used to watch it obsessively when she was a child, too, wide-eyed with disbelief that someone who looked even remotely like her was the star of a Disney film. She made her mom buy her a Pocahontas costume for Halloween when she was six, only instead of a Native girl on the package modeling the cheap imitation buckskin, there was a little blond white girl. Her Pocahontas obsession waned significantly after that.

Alice was busy trying to craft the perfect text to respond to Mason’s rather lackluster “k” after she sent him her aunt’s address. She settled on “c u soon,” then immediately reported back to each of her friends to get their reactions. She barely noticed when Dana sat up and cocked her head to the side, her parroting of every word silenced as she stared in confusion at the screen.

“That’s wrong,” she said.

“What?” Alice asked, distracted.

“Pocahontas sang the wrong thing.”

“You probably just heard it wrong.”

“No,” Dana said, her lower lip protruding. “She said it wrong. She’s supposed to sing, ‘Should I marry Kocoum?’ This time it was something . . . weird.”

Alice’s eyes were glued to her phone screen. There were happy texts congratulating her; there were snide texts pointing out Alice was last at everything, from getting boobs to losing her virginity; there were conciliatory texts warning her it wouldn’t hurt that bad, that even if it did, it probably wouldn’t last long anyway. There were some very exaggerated— and somehow very sexual— emoticons.

“Alice. Alice. ALICE! You’re not even listening.”

“Yes, I am.” She looked up to find her cousin standing in front of her, her tiny face scrunched in indignation. “Pocahontas sang the song wrong. What’s the big deal? She probably just forgot.” Alice liked making outrageous comments like that to her baby cousin. Even at her young age, Dana had surprisingly good bullshit radar, which made it even more funny when seemingly adult comments came out in her childish voice.

“Oh, for crying out loud. Now you’re being ridiculous,” Dana said in a perfect imitation of her mother, rolling her eyes and turning back to the screen. Alice stifled her laughter. She didn’t realize Dana knew how to roll her eyes. She made a mental note to tell her aunt about this development later.

Even with that little outburst, it didn’t take long until Dana was snoring, arching her small body across Alice’s lap, her belly swollen with sugar and soda. It was eight p.m. and Mason was due to show up in an hour. Open bags of Cheetos and plates still thick with ketchup lined the floor like offerings to some prediabetic god. Alice didn’t eat any of it, she was too worried. What if she had bad breath when Mason kissed her? He’d tell all his friends, who’d tell all their friends, and it’d mark her as gross and undatable. She couldn’t risk it. She popped gum into her mouth instead and chewed with purpose.

She carried Dana to bed, cocooned her in her faded Mickey Mouse comforter, then gazed down at her, brushing a stray black hair from her face. She looked so serene, like she knew she was completely safe. Alice wondered when she last looked like that herself, if she’d ever look like that again.

She kissed her cousin on the forehead. “Don’t grow up,” she whispered as she pulled the door closed.

In the living room, Alice gingerly picked up bags of chips and chewed cookies, half worried she’d contract their calories like a virus and become bloated and ugly. Her stomach groaned with each whiff of salty grease or baked sweets. It felt empty, wrung out, a hunger past pain. She chewed her gum, checked her phone.

“Put your phone down. We need to talk.”

Alice spun around, terrified.

No one was there. But from the sound of the voice, the speaker was close.

“Hello?” she called.

“You’re about to make a big mistake.”

The words were harsh, accusing; the voice familiar but strange. There was water on the TV screen, making the entire room glow blue. It was the part of the movie where John Smith first saw Pocahontas: a sexless silhouette in the fog, a target for his gun, another body to brag about to his shipmates once his trigger finger squeezed.

Slowly, Alice backed up toward the kitchen. She needed to get her hands on one of her aunt’s knives. They were all so dull they could barely peel a potato, but at least they looked menacing.

“Is someone there?” Alice asked, her heart beating fast.

“Of course someone’s here. I talked to you, didn’t I?”

At that, Alice ran to the knife drawer, yanked it open, pulled out the biggest one, then nervously walked back in the direction of the voice in the living room.

“I— I’ve got a knife, but if you leave right now, I won’t use it.” She wasn’t sure she’d be able to use it. She was a kid, not a killer. But if it came down to this weird person or her and Dana, she knew who she’d pick. Theoretically.

Just then, Pocahontas laughed and leaped toward her, stopping just short of the thirty-two-inch TV screen that held her in a handdrawn prison. “And how, exactly, are you gonna use that big old thing on me?”

“What the fuuuuuuck!” Alice yelled as she ran back to the kitchen and dove under the table. Her breathing got short and fast, almost as quick as her heartbeat. “Whatthefuckwhatthefuckwhatthefuck. This isn’t real. This can’t be real.”

“Well, it is. Deal with it,” Pocahontas called back.

Alice screamed, dropped the knife, and started rubbing furiously at the tears pooling in her eyes. She rubbed until they hurt. If she could feel pain, that meant this wasn’t a dream. Right?

“Is he cute?” Pocahontas called, softer now, across the distance.

“What?” Alice asked as she poked her head out from the table, too startled by the question and the sudden change in tone to realize she was taking the bait. “Who?”

“The boy you’re cleaning up for.”

Shit. Mason. What if he got here and this . . . whatever this was . . . was still happening? Alice looked out at the microwave clock. 8:32 p.m. Twenty-eight minutes before Mason got here. Twentyeight minutes for her to deal with whatever was happening and get her shit together. She took a deep breath and stood up on shaky legs, then approached the TV.

“He’s okay, yeah.”

Pocahontas watched her approach curiously, something nearing a grin playing at the corner of her lips. Her voice like poisoned honey.

“Oh, come on. He must be better than ‘okay.’ I saw this place a few minutes ago. Total disaster. You don’t put in this kind of effort for a guy who’s just ‘okay.’”

“I mean, I wouldn’t betray everyone I’ve ever loved for him, but I’d really strongly consider it.” Alice was trying to play it cool, using her sarcasm like a mallet to flatten all other emotions. She found that once she accepted that the situation was happening, it became much less scary, almost normal, even. It didn’t cross her mind that what she should be scared of was how quickly she adjusted to something so strange and terrifying. It wouldn’t for some time.

“He’s not named John, is he? I’ve known two Johns. Both of them ruined my life.” Pocahontas delivered the words casually, dispassionately, as if she weren’t talking about herself at all but some hypothetical self in some hypothetical universe.

“Oh, please. I’ve seen this movie a million times. John Smith doesn’t ruin your life. You go your separate ways at the end, but he would have stayed if you asked him to. He loves you.”

Pocahontas chuckled. “The only thing John Smith loves is killing savages. Didn’t you watch the opening scene? He sings a whole song about it.”

“Well, yeah, but that was before. He doesn’t kill you.”

Pocahontas smiled bitterly. “There’s more than one way to kill a person.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

Pocahontas opened her mouth, then closed it quick. As Alice watched, waiting for an explanation, she saw Pocahontas’s face twist and grow into an otherworldly mask, her eyes crooked and sliding down her cheek like egg yolks. She squeezed her own eyes shut, shaking.

“Alice?”

How does she know my name? Alice wondered. She felt sick. All of this was wrong. Some sort of cruel game, maybe. Yes, her instincts told her, a game. And in this game she couldn’t let Pocahontas know the effect she was having on her.

“Who the hell are you? I know you’re not really Pocahontas,” Alice said defiantly, popping her eyes back open. She tried to make her face blank.

The princess’s laugh rang out in Dolby Digital surround sound— pitch-perfect, slightly manic. But then, as it went on one beat, two beats, three beats too long, it shifted. The sound became louder, shr iller, and more supernatural, less a laugh and more a punishment.

“Shhhhhhhh!” begged Alice, worried the noise would wake Dana.

“That’s true,” she quietly replied in a calm though amused tone. “I’m definitely not Pocahontas.” She straightened her spine, then lengthened her neck. “Matoaka. That was what everyone in my village called me. This was back before John Smith and his stupid little stories. Don’t bother trying to pronounce it, by the way. Your clumsy English tongue will ruin the rhythm.”

There was a certain music to the princess’s real name, something that reminded Alice of oceans she’d never seen, waters she’d never swum. It was a peculiar feeling, one she instinctively knew no English word could replicate. But all things considered, she didn’t want to play nice. She preferred to make the princess wince.

“Pocahontas is better.”

“You would think that name’s better.” The princess rolled her eyes. “I remember you. Back from when you were that girl’s age,” she gestured in the general direction of Dana’s room. “You watched this perverted version of my story all the time. Just loved it. Knew the words to all the songs. Even ‘Savages.’ I’ll never understand why Native kids sing along to that one.”

“I didn’t know what the song meant back then,” Alice said defensively. “I was a little kid.”

“And I was a little kid when I met John Smith. All of ten years old. Did you know that?”

“No,” Alice replied, startled. “Does that mean he’s, like, a pedophile?”

“I don’t know about that. He’s a liar. I was never in love with him. I just played with the kids at his camp. But once I got famous in England he made up this dramatic story about me falling for him and saving his life. Really tired tragic romance stuff. Anyway, enough people believed it and now I’m stuck here”—she threw her arms wide—“painting with all the colors of the wind.”

Alice paused, considering.

“You said two Johns ruined your life. Who’s the second one?”

“John Rolfe. My second husband. I met him after the English kidnapped me.”

“Wait, they kidnapped you?”

“Sure did. It was awful. When John Rolfe came along proclaiming his love, it was the best protection I could get at the time, so when he proposed I said yes. Then I got baptized and had to change my name to Rebecca. Rebecca Rolfe.” She made a face. “Can you believe that alliteration? I prefer Pocahontas to that monstrosity. After that, my husband paraded me around England like a circus attraction for a few years. I gave birth to his brat and died of pneumonia in some ugly English town at twenty-one. The producers left all that out of the sequel, for obvious reasons.”

Alice felt overwhelmed by the many contradictions to the story she thought she knew. How could so many people see such injustice and consciously rewrite it as triumph and romance? But she had to remember: Pocahontas was playing a game. Alice couldn’t let any creeping empathy slide in. She had to cut herself off emotionally from this person and her claimed tragedies, no matter how horrific. So she scoffed at the screen, the terrifying way teenagers can when they want to show how little they care about anything outside themselves. “Okay, your life sucked. Am I supposed to feel bad for you now?”

Pocahontas shrugged. “I can’t tell you how to feel. Enough about me. I want to know more about this guy coming over. He’s totally going to ruin your life, you know.”

“He won’t ruin—”

“Oh, believe me, he will. He can’t help it. He’s your John.”

“Mason isn’t white, so he can’t be my John.”

“You think white guys are the only ones capable of ruining a Native girl’s life?”

Alice felt her stomach contract in disappointment and embarrassment, but also in recognition. She was absolutely right. Mason’s race didn’t really matter in the long run. He could still be her John. The one who took her story and changed it to best fit his narrative, oblivious to any impacts it might have on her. In fact, judging by the state of his many ex-girlfriends and ex-snags, he’d already been the John in many of their young lives. Why would it be any different for her? She couldn’t say that, though. She couldn’t even really allow herself to think it. Not after all the expectations she’d set up. This boy coming over was the weak peg Alice had hung all her selfconfidence on. Even the smallest jostle would send it tumbling to the floor, and where would she be then? The same stupid virgin wishing for a boyfriend she’d been since forever.

“You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Why else do you think I’m here? I have a message for you. About him.”

Alice couldn’t believe the difference in Pocahontas’s tone. How exasperated she sounded. How jaded. As if she was the one exhausted by this game. And even though Alice, in true Alice form, didn’t want to hear what she didn’t want to hear, there was also a part of her aching to know what it was that made Pocahontas come to her, a random girl on Six Nations. If that was in fact what was happening; Alice couldn’t really be sure. Whatever it was that Pocahontas wanted to say, though, it had its hooks in her.

“Who’s the message from?”

“Sorry, can’t say. It’s against the rules.”

“What rules?”

“Can’t say. That’s against the rules, too.”

“Are you serious?” Alice asked. “How am I supposed to . . .” But even as the words left her mouth, she knew there was no point in asking any further. She wouldn’t get the clarity she wanted. Each answer was like opening a closed door, only to find ten closed doors behind that one, and ten more closed doors behind the next, questions endlessly becoming more questions, a maze forever expanding. Alice simply didn’t have it in her to puzzle any of this out.

Pocahontas smiled with pity, then carefully sat on top of some rocks, ever regal. Her face had no wrinkles, but she looked old and anguished all the same. Her eyes clenched shut. The confidence, the sarcasm, the bravado— it dawned on Alice that it was all an act. Maybe the spirit of a little Powhatan girl really was trapped in this movie, inside a story that was never hers, stuck replaying the lies other people told about her over and over. And maybe she really was trying to connect with Alice, another Native girl who felt in many ways trapped in the stories people told about her. In this way, Pocahontas brought to mind every woman Alice had ever known: her aunt with her seed beads and bruises, her mother with her bloodshot eyes and constant work, her friends with their push-up bras and pushy boyfriends. Herself. Women like porcelain dolls with hairline cracks trying to smile and smile as hammers came down all around. When Alice thought about it, even the Haudenosaunee Creation Story wasn’t free from this grief; in some versions Sky Woman only fell to earth because her angry husband had pushed her. Was it always like that for women? Would the story, the cycle, ever stop repeating? Mason didn’t even know her name, and here she was, ready to give him anything he wanted. What did she really know about him, anyway?

“What’s the message?” Alice asked, still cautious.

“Stay away from Mason. He is your John. One of them. You’re meant for other things— better things, even— but if you don’t start being more careful with men now . . . things will get very, very bad for you.”

Alice sank into the cushions of the old couch and let her head fall back. As she stared at the ceiling, she started to think about what this choice would cost her. How Mason would trash-talk her at school if she flaked out on him. How he’d tell everyone what happened and she’d be called something stupid that would sting nevertheless. Something like a cold pussy or a prude or a pathetic little virgin. She’d have to figure out some excuse to make to her friends, who would definitely roast her for letting the same guy she talked to them about incessantly for years get away. It was minutes before Mason was supposed to arrive, and the idea of turning him down was in many ways inconceivable. It already felt like a mistake, and she hadn’t even made it yet.

“Why should I believe you? You could be making all this up,” Alice said as she rolled her head forward. “What am I even saying? You are made up. You’re a fucking cartoon.”

“That’s not all I am.”

Pocahontas’s face warped and grew again. It took up the whole screen, the strands of her black hair whipping around, her brown face melting like wax, a sickening dripdripdrip sound coming from the speakers. The black strands kept squirming, and Alice realized they weren’t hair at all but great black snakes. Each one’s eyes glowed yellow as their heads turned to the screen, to Alice, and began stabbing their noses against the glass—BANG! BANG! BANG!—until the screen finally cracked, and then the snake heads were out in her world, were real, their tongues darting in and out from between their fangs. Alice cried out, frozen, as words were whispered into the conch of her ear: Turn it off. Yes. She would turn it off. She had to. Her eyes raced around the living room; she saw the remote resting on top of the side table, and she grabbed it.

“Wait—”

She clicked it off just as Dana screamed from her bed.

Alice didn’t even think. She ran to her cousin’s room, worried the black snakes had somehow burst through her window and started attacking her. As soon as she turned the corner, though, she saw the room was the same as she had left it. There was little Dana, holding the stuffed parrot she’d named Meeko. She had her blankets pulled up to her eyes and she was crying, but there was nothing hurting her.

“Why were you yelling?” Dana’s little lower lip trembled.

Alice moved into the room and threw her arms around her fast.

“I’m so sorry, Danabear. I was watching a scary movie, and the bad guy jumped out from the dark. It right spooked me,” Alice lied, hoping her laughter didn’t sound too fake. “I almost fell off the couch.”

“I told you not to watch those,” Dana said, her indignation slowly taking over from her fear. “They’re bad.”

“I know. You’re right. Give me a sec and I’ll go turn that silly movie off and come cuddle with you.”

Alice stepped out of the bedroom, then leaned against the wall. She was sweating heavily, and her heart was thrashing inside her, but Dana was fine. They were both fine. Whatever was happening to her had seemingly stopped. She took one long, steadying breath, then cautiously walked back to the living room.

Things looked normal. No snakes. No cracked TV screen. Alice picked up the remote control, tension threaded through her muscles, and turned the TV back on.

The DVD menu was on its familiar loop.

It was like the whole thing never happened. Maybe it didn’t, she thought. Maybe I’m crazy. A rush of shame and guilt overcame her. Alice knew people had said her grandma, who died when she was still a toddler, was crazy. Not often. Most people seemed to not want to talk about her grandma at all, not even Ma or Aunt Rachel.

But it felt so real.

She stared at her phone: 8:55 p.m. Five minutes until Mason was supposed to get there.

Alice had a choice to make, and the quivering anxiety she felt told her she had already made it. She took a deep breath, then focused back on her phone. She could practically hear Melita screaming at her as she typed the text out: “sorry change of plans. can’t meet up after all. babysitting.”

This time Mason replied quickly.

“fuckin cock teaze”

Then: “didn’t want u anyway u fat ugly bitch”

Then a slew of more messages Alice couldn’t bear to even open.

Underneath the crushing certainty that her worst fears about a future with Mason were now realized, leaving her single and inexperienced as she entered high school, and well beneath the nausea worming its way through her still-empty stomach at what this whole experience meant for her and her sanity, there remained a small part of Alice that couldn’t help but think, couldn’t help but wonder, couldn’t help but hope: maybe Pocahontas was right, after all. Maybe Mason was her John.

CHAPTER 1

The Last Exit Out of Alice

Yes, this is technically called “The Creation Story,” but it’s not the beginning, so let’s get that little misconception out of the way right now. There never was a beginning. There was a before, and before that was another before, and another before before that. I know that’s probably confusing to a modern mind like yours. Colonialism and so-called linear time have ruined us. We can’t even wrap our heads around our own stories because we’ve been trained to think in good, straight, Christian lines.

But the world doesn’t work like that. It never has.

Anyway, before before, this world was covered in water. A deep ocean that held water creatures like pearls. An endless sky that bore witness to the brilliance of the birds. Now, when I say “sky,” some outer space is included in there, too. A lot of outer space, actually. Pretty much anything that can be seen from earth counts as “sky”—but that’s not to be confused with Sky World, which is even higher than the sky. It’s its own world with its own problems, as you’ll see pretty clearly once we get into Sky Woman and her life. Though when you really stop and think about it, Sky World and its problems aren’t that different from our world or our problems, so it might as well be just plain old “the World.”

Aaaand there I go, getting ahead of myself again. Sorry. Bad storyteller! (Let me ask you a quick question: When I say that—“Bad storyteller!”—do you imagine a white lady with a pursed butthole of a mouth wagging her finger in your face, too? Maybe like a nun? “Bad storyteller!” Wag. “Bad Indian!” Wag wag. “Bad woman bad human bad subhuman bad unreal unholy object bad possession my possession his possession everyone’s possession but your own bad bad bad bad badddd!” Wag wag wag wag wag. No? Just me? All right, I’ll remember that for later. See? Not that bad a storyteller.)

So. Basically. The order of things went, from top down:

And at the very, very bottom of the ocean, the animals heard, there was something called clay.

They weren’t sure, mind you, but they most certainly suspected. Heard from a friend’s sister’s boyfriend’s cousin, and they all but confirmed it. The animals have always been a gossipy bunch.

No one had ever seen this “clay” or felt this “clay” or taken grainy, possibly doctored pictures of this “clay” to pass around and praise or debunk, however—so most of the animals laughed the whole thing off. Everyone knew there was only sea and sky. Sink or swim.

Or fly, I guess.

“Somebody’s hungry . . .”

I jump in my seat, nearly choking on a gasp. My hand automatically flies to my chest, as if to hold in my thundering heart, and I whip around.

Steve stands there, Dawn wriggling uneasily in his arms.

“Oh. It’s you,” I say, exhaling with a little laugh.

“Didn’t mean to scare you.”

“It’s okay. I was . . . in the zone, I guess,” I say, turning back to look at the computer screen, at the pitiful number of words I’ve managed to squeeze out. I’ve been writing and rewriting and erasing and editing this opening section for weeks and nothing seems right. I want to get it perfect, to capture the way my dad used to tell our traditional stories when I was a kid. It’s only now, as I labor over even the smallest word, wondering if it’s the right kindling to stoke the fire of the reader’s mind, that I understand how much talent and effort it took him to make our stories seem so urgent and relevant, even hundreds, thousands of years later. I doubt I’ll ever come close to the bar he set. I mindlessly tap the space bar on my laptop, as if that will add anything substantial to the story.

I have no idea how the hell Steve and Dawn snuck up on me. For one thing, I can usually smell his cologne from ten feet away. His mother, Joan, bought it for him. She thinks because she spent more than five hundred dollars on it and its heavy bottle is bedazzled with enough Swarovski crystals to make a drag queen feel faint, that it must smell good. It doesn’t. It smells like an unwashed-for-a-couple-days-patchouli-loving douchebag. Like what I imagine Jared Leto smells like. Plus, I’m pretty sure I’m allergic to it because my nose starts to run whenever he sprays, delays, and walks away. (“Learned that one from Queer Eye,” he told me once, smiling with characteristic earnestness.)

I know he’s wearing it as a tribute to his doting mother, an act of olfactory love, and that if I even suggest I don’t like it he’ll stop immediately. But I also know Joan has been passive-aggressively planting the idea that I unfairly hate her ever since she and I first met, seeds of doubt that were no doubt fertilized and watered by my insistence on having a wedding that centered my rez family and friends. Even saying that I hate the cologne she bought him could subconsciously confirm these suspicions. They’re accurate—I absolutely hate her. But I don’t want him to know that, so I suffer both the smell and the snot, smiling like a good little wife.

The other thing: I definitely should have heard Dawn. She’s not quite crying but making an agitated sort of mewling sound I’m all too familiar with. It usually signals that she’s about to start another hours-long crying spree. I’m so attuned to that sound I can already feel my breasts leaking. They clearly heard her long before I did. But, if I feed her fast enough, before she starts really getting her little lungs going, maybe we’ll avoid a fit this time.

I turn back to the two of them and hold my hands out for Dawn. “Give her here.”

Steve plops her into my arms. I pull up my shirt, pull down the flap on my breastfeeding bra, and pray that Dawn will latch on this time. Miraculously, she does, her little cheeks moving in and out like a goldfish. Her face fades from burgundy to a calm light brown as I rub her velvet cheek, soft the way only brand-new baby skin is. Relief floods my muscles, and I close my eyes, letting this small victory loosen my too-tense body. We sit like this for some time, our shared exhaustion making us unlikely allies.

“I like how the animals are all conspiracy theorists.”

Shit. He’s talking about my writing. I left it up. Stupid mistake. I immediately open my eyes, see Steve leaning over me, and cringe. Not because I don’t want him near me. I do. There’s this amazing warmth he emits, which makes any room he’s in feel like the temperature has risen a few degrees from his mere presence, the exact opposite of the way demons and ghosts are said to make rooms colder.

No, I cringe because his seeing my writing at this stage feels too revealing. Like a stranger walking in on me half naked in a fitting room. Even his praise prickles. The writing is too fresh, too close, my meandering through it too sensitive for scrutiny.

“Thanks, babe. That’s sweet of you to say. But it’s not good. And it’s definitely not ready to be read yet.”

I slam my laptop shut, and he stands up quick.

“Oh. Sorry. Didn’t realize you were keeping it secret.”

Steve moves away from me, hurt, and my once warm neck becomes cold again. I feel a pang of shame—so deep and sharp and fleeting I can’t possibly follow it back to its roots—quickly swallowed up by regret. I’m doing it again. Pushing Steve away. He’s excited about my writing. He wants to encourage me, he wants me to succeed, he’s told me as much, said we need to set goals for ourselves as individuals and as a family so we maintain our autonomy. He doesn’t deserve this.

“It’s not that it’s a secret. It’s just . . . ,” I start, searching for a way to invite him back in again. “I’m worried about the tone,” I finally say, looking up at him through lowered eyelashes, hoping my face is soft and feminine instead of hard and masculine. It takes conscious effort for me to do that—look helpless, vulnerable, innocent—in a way I’m sure would come naturally to so many white women.

“Maybe it’s too flippant?” I add for emphasis.

Steve smiles very slightly, almost imperceptibly. “I like the tone,” he says, his voice tentative. “It’s ballsy,” he continues. “Totally different from the old sage Indian everyone thinks of whenever anybody says the words ‘creation story.’”

Not everyone thinks of that, I want to say. White people think of that.

I look down at Dawn, trying to see parts of my family members’ faces in her tiny features, but I fail. She’s asleep now. Fighting naps all day has finally caught up with her. I pull myself out of her mouth and fix my bra and shirt.

“I don’t know if Ma would like it,” I confess quietly. “Or Dad.”

“What are you talking about? They’d both love it,” Steve says as he bends down and kisses my hairline. He gently pulls Dawn away from me and sets her into her car seat in the corner of the office. I’m not sure when I put it there.

I get up, move over to the window. Glance out through the blinds to see the driveway and cream siding of our neighbor’s house. People don’t exactly live here for the views, I have to remind myself.

“Anyway, don’t worry about anyone else’s opinion. Only Shonkwaia’tison can judge you,” he says, grinning with obvious pride.

I pause.

Shonkwaia’tison.

Today was Steve’s first language class, I remember. He was there, in some yellow-tinged classroom reading handouts and forcing his hard English tongue to make soft Mohawk sounds, while I was here, pretending I know how to write Mohawk stories in English words. It’s difficult not to be jealous of him, embarrassed of myself. He slid the Mohawk in so seamlessly, so confidently. The same way he approaches everything, including me, as he slips behind me once more, his hot hands skating over my hips, my abdomen.

And suddenly I’m in the upper corner of the room, looking down at Steve and me, as the empty shell of myself leans into the delicious heat of his body. I try not to panic. This isn’t exactly new: my consciousness peeling away from the inconvenient reality of my body and floating into the strange, almost liquid-feeling air nearby. But I’m more determined now than ever before: I can’t let old demons ruin my new life. They’re trying, the demons. Pushing against the mental membrane I’ve been fortifying since I was a teenager.

Just last week I was making dinner, standing in the kitchen in the sleek little dress I’d grabbed from the closet and shimmied into so Steve would see how well I was handling everything. I’d thrown my hair into an updo I learned from Instagram but decided against makeup. That seemed too try-hard. I had just placed some handbreaded chicken cutlets into the oven when my eyes caught on the terra-cotta-colored walls. I started thinking about how much I hated them. Steve had chosen the paint. Steve had chosen everything. He’d asked for my input when we first moved in, but I’d shrugged. I couldn’t consider the world outside my grief. Ma was newly dead, and I was spending most of my time back at my childhood home on the rez, preparing for her funeral. I’d passed a few sleepless nights in her bed, her sheets pressed to my nose as I breathed in her scent of menthol cigarettes and Chanel No5, sobbing. In the mornings, I’d wandered through the trailer, covering the mirrors and reluctantly bagging her belongings to give away after the burial. I’d originally wanted a house with a granny suite so I could look after Ma, make sure she wasn’t pushing herself too hard. She’d been struggling with the long-term effects of an injury then, and I wasn’t sure how well she’d adjust to living without me for the first time. Once I found out Joan was paying for the house, though, I didn’t feel comfortable mentioning it, or any of my preferences. She made it clear the only opinion that mattered was her own. I couldn’t help but focus on this fact after Ma died—she could have been living with us, we could have saved her—letting it curdle into resentment for both my mother-in-law and the house she’d gifted us. Devoting any thought to decorating it in the weeks and months that followed seemed impossible, even cruel.

And now, thanks to Steve, our entire house looks like it was ripped from an IKEA catalog—all clean lines and no character. White cupboards and chrome pendant lamps and black cube couches. I’m scared to move inside it, scared to dirty it, to disrupt its sanitary perfection. My stylish yet affordable Swedish-designed prison. My first place off the rez, and yet not mine at all.

I don’t belong here. Even though it was just a thought, it boomed loud in my mind as I watched the water in the pasta pot come to a boil. I trembled at the truth of it. I don’t belong anywhere. Not anymore.

Then another voice, not my own: It’s all burning.

It startled me, this voice, and for a moment I was so scared I couldn’t move. I saw it first: dark smoke reaching from the oven door and up toward the ceiling like an angry, vengeful hand. Holy shit, I thought. Something really is on fire. As soon as the thought popped in my head, the sound of the fire alarm echoed in my ears, then the sound of Dawn’s confused yelps started in the living room like high-pitched harmonies. I knew logically those sounds must have been going for a while by that time, but for some reason I hadn’t heard them.

It was like my body suddenly went on autopilot. I grabbed oven mitts, opened the oven door, snatched the baking sheet, slammed the door shut, and dropped the baking sheet into the sink with a clatter. I turned on the taps, anxiety sharp in my chest as I watched the steady stream of water rush over the charred remains. As I ran to grab a broom so I could turn off the smoke alarm with the end of its handle, it occurred to me that Steve was due back any minute. He couldn’t see this. He couldn’t see any of it.

Once I’d stopped the alarm, I unclipped Dawn from her car seat and held her to my chest, shushing her as I plotted. If I called Steve and told him we were out of diapers but insisted he had to buy a specific brand that he would have to drive across town for, that could buy me another half hour. I could order some chicken on a delivery app, set it out on our plates at the dinner table, then tie up the garbage with the burned chicken and run the dishes through the dishwasher. No evidence. It’d be like it never even happened.

Everything went according to plan. I thought I was in the clear. But then, while we were eating dinner, the demons came back for more. At first, everything seemed normal. Steve had launched into the minutiae of his day—how the head of the department invited him out for lunch, which he thought would help with his tenure. Then he went on about the progress of his colleague Scott’s home reno, then his department head Lou’s wife Sheila’s latest publication. He didn’t ask me how my day was in all that time. Part of me was relieved since I didn’t have to lie. The other part of me was nearly vibrating with so much swallowed rage. If Sheila’s day mattered, and Scott’s day mattered, why the fuck didn’t mine?

“Well, Steve,” I might have said if I had any spine, “I nearly burned down the house while you were gone. This dress I threw on just for you now stinks like baby puke and sweat. Your daughter doesn’t want the milk from my tits, so I’m always sore and she’s always crying. I can’t sleep at all. And I never want to fuck you or anyone again.”

He’d probably still find a way to excuse my rudeness, to paint it as some endearing joke. He’s that type of person. Endlessly optimistic, incredibly loving. The type of person who genuinely tries to get to know people, and once he does, focuses almost exclusively on the good in them, using their past circumstances to explain away what others might refer to as shitty behavior. The type of person who listens deeply to everything everyone says to him, remembers the tiniest, most otherwise inconsequential details of each conversation, then asks about them whenever he sees you next, whether that’s in a week or six months. His attitude toward others made everything infinitely more interesting, like each interaction had the possibility to unfold into a fascinating short story, complete with rich characters and unearthed complexities. By the time I was getting ready to move off the rez, my cousin Tanya joked people were going to miss Steve’s visits more than they were gonna miss me. I admired that he was so likable, with his constant kindness and focused interest. I still do.

But that night, after the fire scare and the rush to figure out dinner and the droning conversation, I couldn’t think about any of that. I was silently simmering, unsure how to put out the blaze inside me. Maybe that played a role, like a key unlocking a door.

Steve finished his meal and shouted, “Nya:wen!” Exaggerating the last syllable the way he always does because he knows it makes me laugh. Or it did. Before Ma died and Dawn was born and I disappeared.

“Nyoh,” I replied quietly, shoveling a forkful of salad into my mouth.

“Oh, guess what?” he asked as he swept my plate into the dishwasher. “U of T is offering a beginner Mohawk class this year. I talked to the head of my department and they’re going to pay for me to enroll. I managed to convince him it’ll benefit the department to have staff who speak Mohawk. Isn’t that great?”