9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Oldcastle Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

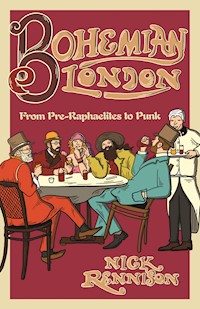

London has always been home to outsiders. To people who won't, or can't, abide by the conventions of respectable society. For close to two centuries, these misfit individualists have had a name. They have been called Bohemians. This book is an entertaining, anecdotal history of Bohemian London. A guide to its more colourful inhabitants. Rossetti and Swinburne, defying the morality of high Victorian England. Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley in the decadent 1890s. The Bloomsburyites and the Bright Young Things. Dylan Thomas, boozing in the Blitz, and Francis Bacon and his cronies, wasting time and getting wasted in 1950s Soho. It's also a guide to the places where Bohemia has flourished. The legendary Café Royal, a home from home to artists and writers for nearly a century. The Cave of the Golden Calf, a WW1 nightclub run by the Swedish playwright August Strindberg's widow, The Colony Room, the infamous drinking den presided over by the gloriously foul-mouthed Muriel Belcher, and the Gargoyle Club in Dean Street where the artistic avant-garde mixed with upper-crust eccentrics. The pubs of Fitzrovia where the painters Augustus John and Nina Hamnett rubbed shoulders with the occultist Aleister Crowley and the short-story writer Julian Maclaren-Ross, wearing mirror sunglasses and clutching a silver-topped Malacca cane, held court for his acolytes and admirers. The story of Bohemian London is one of drink and drugs, sex and death, excess and indulgence. It's also a story of achievement and success. Some of the finest art and literature of the last two centuries has emerged from Bohemia. Nick Rennison's book provides a lively and enjoyable portrait of the world in which Bohemian Londoners once lived.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

BOHEMIAN LONDON

London has always been home to outsiders. To people who won’t, or can’t, abide by the conventions of respectable society. For close to two centuries these misfit individualists have had a name. They have been called Bohemians.

This book is an entertaining, anecdotal history of Bohemian London. A guide to its more colourful inhabitants. Rossetti and Swinburne, defying the morality of high Victorian England. Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley in the decadent 1890s. The Bloomsburyites and the Bright Young Things. Dylan Thomas, boozing in the Blitz, and Francis Bacon and his cronies, wasting time and getting wasted in 1950s Soho.

It’s also a guide to the places where Bohemia has flourished. The legendary Café Royal, a home from home to artists and writers for nearly a century. The Cave of the Golden Calf, a First World War nightclub run by the Swedish playwright August Strindberg’s widow. The Colony Room, the infamous drinking den presided over by the gloriously foul-mouthed Muriel Belcher, and the Gargoyle Club in Dean Street where the artistic avant-garde mixed with upper-crust eccentrics. The pubs of Fitzrovia where the painters Augustus John and Nina Hamnett rubbed shoulders with the occultist Aleister Crowley and the short-story writer Julian Maclaren-Ross, wearing mirror sunglasses and clutching a silver-topped Malacca cane, held court for his acolytes and admirers.

The story of Bohemian London is one of drink and drugs, sex and death, excess and indulgence. It’s also a story of achievement and success. Some of the finest art and literature of the last two centuries has emerged from Bohemia. Nick Rennison’s book provides a lively and enjoyable portrait of the world in which Bohemian Londoners once lived.

About the author

Nick Rennison is a writer, editor and bookseller. He has published books on a wide variety of subjects from Sherlock Holmes to London’s blue plaques. He is a regular reviewer for the Sunday Times and for BBC History Magazine. His titles for Pocket Essentials include Sigmund Freud, Peter MarkRoget: The Man Who Became a Book,Robin Hood: Myth, History & Culture and A Short History of Polar Exploration. He has edited three collections of short stories for No Exit Press, The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes, The Rivals of Dracula and Supernatural Sherlocks. He lives near Manchester.

Contents

Introduction

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Epilogue

Bibliography

Copyright

Introduction

‘“Bohemia”… is both a state of mind and a place’

Robert Hewison,Under Siege

Londonhas always been home to outsiders. To people who won’t, or can’t, abide by the conventions of respectable society. For close to two centuries these misfit individualists have had a name. They have been called bohemians. This book aims to provide a short introduction to bohemian London. It opens with a chapter devoted to those writers and artists, from the Renaissance to the Romantic era, who were bohemians before the word, in its current sense, was invented. It moves on to the creation of modern ‘bohemia’ in 1830s and 1840s Paris and to its incarnation across the Channel a few years later. The chapters that follow explore the world of London bohemians across a dozen decades. Rossetti and Swinburne, defying the morality of High Victorian England. Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley in the decadent 1890s. The Bloomsburyites and the Bright Young Things. Dylan Thomas, boozing in the Blitz, and Francis Bacon and his cronies, wasting time and getting wasted in 1950s Soho. It concludes with the punks of the 1970s and a chapter that looks at what has happened to London’s bohemia in the last forty years.

This is a story of places as well as people, a matter of topography as well as biography. The history of bohemian London can be traced across a map of the capital from Chelsea and Bloomsbury to Soho and Fitzrovia. And just as no such history should omit, say, Francis Bacon or Nina Hamnett, no record of it can ignore the pubs and clubs in which they and their fellows drank, talked and swapped ideas. The legendary Café Royal, a home from home to artists and writers for nearly a century. The Cave of the Golden Calf, a First World War nightclub run by the Swedish playwright August Strindberg’s widow. The Colony Room, the infamous drinking den presided over by the gloriously foul-mouthed Muriel Belcher, and the Gargoyle Club in Dean Street where the artistic avant-garde mixed with upper-crust eccentrics. The Fitzroy Tavern and the Wheatsheaf where the painter Augustus John rubbed shoulders with the occultist Aleister Crowley, and the short-story writer Julian Maclaren-Ross, wearing mirror sunglasses and clutching a silver-topped Malacca cane, held court for his acolytes and admirers.

The history of bohemian London is one of drink and drugs, sex and death, excess and indulgence. It’s also one of achievement and success. Some of the finest art and literature of the last two centuries has emerged from bohemia. It is a complicated history which a book of this length can only outline in its essentials, but it is also, as I hope I have made clear in the following pages, endlessly fascinating.

Chapter One

BOHEMIA BEFORE IT HAD A NAME

Shakespearean Rogues and Restoration Roisterers

To Shakespeareand his contemporaries, the word ‘Bohemia’ would have signified nothing more than the name of a faraway country of which they knew little. InThe Winter’s Tale, the Bard famously gets his geography in a muddle and gives Bohemia a coast on the sea when it had none. During the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, the use of ‘bohemian’ to describe the unconventional or the artistic was 250 years in the future. Yet many of the playwrights of Shakespeare’s day lived lives that would have undoubtedly been labelled ‘bohemian’ in later centuries. Indeed, some were far more extreme in their flouting of ordinary morality than their descendants in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Later bohemians mostly contented themselves with sex, drugs, drink and not paying their bills. More than one Elizabethan dramatist committed murder. John Day, who had already been expelled from Caius College, Cambridge for stealing books, stabbed to death his fellow playwright Henry Porter in a quarrel in Southwark in 1599. He pleaded guilty to manslaughter, but seems later to have gained a Royal Pardon for his offence. Ben Jonson, author ofVolponeandThe Alchemist, who once described Day as a ‘rogue’ and ‘base fellow’, had himself killed a man the previous year. During a duel in Hoxton, Jonson ended the life of an actor named Gabriel Spenser. He spent time in jail, but was able to escape worse punishment by pleading ‘benefit of clergy’, taking advantage of an old law which excluded the clergy (or, in Jonson’s case, a literate man who could prove his knowledge of Latin) from condemnation by a secular court. He emerged from Newgate Prison with no more than a branded thumb. The most famous of all Shakespeare’s contemporaries, Christopher Marlowe, led a notably rackety life. Accused in his lifetime of atheism, he was also reported to have said that ‘all they who love not tobacco and boys are fools’. He met his end in May 1593 in a Deptford drinking den. Stabbed in the head during what was said to be a brawl over payment of the bill, the greatest dramatist before the advent of Shakespeare may have been a victim of the shady world of espionage in which he sometimes operated.

Although he died at the age of only 29 and his fame was rapidly eclipsed by that of Shakespeare, Marlowe’s gifts were not forgotten and his plays have continued to be regularly performed. The same cannot be said of the man who, more than any other writer of the day, embodied the characteristics we would now call ‘bohemian’. Today, Robert Greene is primarily remembered, if he is remembered at all, for a single disparaging comment about Shakespeare that he made in a pamphlet.Greene’s Groatsworth of Wit, Bought with a Million of Repentanceincludes a description of an unnamed dramatist, assumed to be Shakespeare, as an ‘upstart crow’. It was published in the September of 1592, two weeks after its author had died, allegedly of a surfeit of pickled herring and Rhenish wine, at the age of 34. (Scholarly debate still continues over the question of whether Greene wrote the words for which he is most famous or they were put posthumously into his pamphlet by someone else, probably fellow writer Henry Chettle.) During his lifetime, Greene was renowned both for his writing and his dissolute way of life. A graduate of Cambridge, he nonetheless revelled in the low life of London, spending much of his time in the city’s least reputable taverns and taking as his mistress the sister of a notorious criminal known as ‘Cutting Ball’ who was hanged at Tyburn.

Unknown 21-year old man, supposed to be Christopher Marlowe, 1585, artist unknown

The years of the Civil War and Oliver Cromwell’s rule were not ones likely to encourage bohemianism, although they did see the emergence of several groups who advocated what might today be called ‘alternative lifestyles’. The Diggers, for example, under the leadership of Gerrard Winstanley, established what was, in effect, a commune on land at St George’s Hill, Surrey until the violent opposition of local landlords forced them to abandon it. When the monarchy was restored under Charles II, free rein was given to the kind of aristocratic bad behaviour which can be retrospectively labelled ‘bohemian’. The court was filled with upper-class reprobates such as those Samuel Pepys met on 30 May 1668 when he ‘fell into the company of Harry Killigrew… and young Newport and others, as very rogues as any in the town who were ready to take hold of every woman who come by them’. According to Pepys, ‘their mad bawdy talk did make my heart ache’, but there is no mistaking the prurient delight with which the diarist reported how his new chums told him of a ‘meeting of some young blades… and my Lady Bennet and her ladies and their there dancing naked, and all the roguish things of the world’. ‘Lord, what loose cursed company was this that I was in tonight,’ Pepys concludes, although admitting that it was ‘full of wit; and worth a man’s being in for once, to know the nature of it, and their manner of talk, and lives.’

One of Charles II’s favourites was the dissolute poet and courtier, John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester, who, in the resounding words of Dr Johnson, ‘blazed out his youth and health in lavish voluptuousness’. What Johnson actually meant was that Rochester, like so many bohemians to come, devoted enormous amounts of his time and energy to sex and drink. A poem of the era, written either by or about him, gives a picture of his dissipations which is graphic even by modern standards. The poet describes his typical day: ‘I rise at eleven, I dine about two/I get drunk before seven, and the next thing I do/I send for my whore, when for fear of a clap/I spend in her hand and I spew in her lap.’ The day goes from bad to worse as, unsurprisingly, the woman decides she has had enough of her ungallant lover and disappears with the contents of his purse. ‘I storm and I roar, and I fall in a rage/And missing my whore, I bugger my page/Then, crop-sick all morning, I rail at my men/And in bed I lie yawning till eleven again.’ When not bedding whores and pages or boozing the day away, Rochester was indulging in vendettas and dubiously ethical pranks. He is alleged to have arranged for thugs to beat up rival poet John Dryden, whom he wrongly suspected of writing an anonymous satire in which he was lampooned. (The attack took place near the Lamb and Flag pub in Rose Street, Covent Garden and the site is still marked by a plaque.) On several occasions he adopted the persona of a charlatan healer named Dr Bendo, with premises near Tower Hill, whose specialisation in gynaecological health gave him privileged access to married women. Worn out by his indulgences, and suffering from the combined effects of syphilis, gonorrhoea and alcoholism, Rochester died in 1680 at the age of 33.

portrait of John Wilmot, 2ndEarl of Rochester by Jacob Huysmans, 1665-1670

Among Rochester’s fellow poets and companions in aristocratic hell-raising were Charles Sackville, 6thEarl of Dorset, and Sir Charles Sedley, who outraged public opinion in June 1663 by getting appallingly drunk at a pub in Bow Street called, appropriately enough in view of what happened, the Cock Tavern. According to Samuel Johnson, in his eighteenth-century life of Dorset, the two men went on to the pub’s balcony and ‘exposed themselves to the populace in very indecent postures’. As people booed and bayed for their blood in the street below, Sedley stripped himself entirely naked and harangued the crowd ‘in such profane language that the public indignation was awakened’. Amidst riotous scenes, the drunken poets were driven from the balcony by a shower of stones and later had to face the wrath of the magistrates, who fined Sedley the then huge sum of £500.

Grub Street

In the eighteenth century poverty-stricken poets and writers were not called ‘bohemians’; they were denizens of ‘Grub Street’. Grub Street was a street in Moorfields, which, in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, was, in the words of Samuel Johnson, ‘much inhabited by writers of small histories, dictionaries and temporary poems’. Renamed Milton Street in the nineteenth century, it has now been swallowed up by the Barbican development. In Johnson’s day, Grub Street had not only a topographical reality, but a metaphorical meaning. It became the term applied generally to hack writers and their work, to those who scrabbled and scribbled to make a living in the margins of the literary world. Most of what they churned out was terrible dross, although representative Grub Street figures like the proto-journalist and satirist Tom Brown (1662–1704) and the publican-turned-versifier Ned Ward (1667–1731) sometimes chronicled the urban spectacle of early eighteenth-century London with energy and vigour. Brown’sAmusements Serious and Comical, Calculated for the Meridian of Londonpresents the city as seen through the eyes of both the narrator and an imaginary visitor from India. Ward’sThe London Spyoffers an entertaining panorama of contemporary London life from coffee-house wits to Billingsgate fishwives, from the inhabitants of Bedlam to the courtiers at St James’s Palace.

The greatest contemporary portrait of Grub Street comes inThe Dunciad, Alexander Pope’s scathing denunciation of a literary world presided over by the goddess Dullness, first published in 1728 and revised over the next 15 years. In blisteringly witty verse, Pope holds up a succession of hacks and poetasters for ridicule. It’s the same world conjured up by William Hogarth’s image ofThe Distrest Poet, which he produced first as an oil painting in 1736 and published as an engraving a few years later. Indeed, the artist may well have been inspired by a reading ofThe Dunciad. In a garret room, the harassed versifier struggles to put pen to paper, distracted by the presence of his wife, a crying baby and a milkmaid just arrived at the door to demand payment of her bill. Like Pope, Hogarth has a moral purpose in depicting the scene as he does, but there is no reason to believe thatThe Distrest Poetdoes not reflect something of the reality of Grub Street in its heyday.

Nearly all those unfortunates lambasted by Pope have long been forgotten, their only memorials the lines with which he excoriated them. However, two distinguished literary figures, at least, did emerge from Grub Street. One was Oliver Goldsmith. Later famous as the author of the novelThe Vicar of Wakefieldand the playShe Stoops to Conquer, the Irishman produced tens of thousands of words for very little money during his early days in London. On several occasions he was reduced to staying within the confines of his grubby garret room where the only furniture was a single wooden chair and a window-bench because, in the words of an early biographer, ‘his clothes had become too ragged to submit to daylight scrutiny’. Samuel Johnson tells the story of receiving a frantic message from Goldsmith whose landlady had had him arrested for non-payment of rent. Johnson took possession of the manuscript ofThe Vicar of Wakefieldand sold it to a publisher for £60 which rescued Goldsmith from his debt.

Dr Samuel Johnson reading the manuscript of Oliver Goldsmith’s ‘The vicar of Wakefield’, whilst a baIliff waits with the landlady. Mezzotint by S. Bellin, 1845, after E.M. Ward

Johnson was himself the other great survivor of Grub Street in eighteenth-century literature. He arrived in London from his native Lichfield in 1737. He is now remembered as the imposing figure created by Boswell in his biography, but, before he established his name with the publication of his monumentalDictionary of the English Languagein 1755, he was obliged to churn out vast reams of poems, essays and journalism, all of it for very little money. One of these Grub Street works, first published anonymously in 1744, was hisLife of Richard Savage. If Johnson was a Grub Street escapee, able through luck and his own talents and endeavours to move beyond it, Richard Savage was a man who (metaphorically) lived his entire life there. Johnson knew him and, indeed, developed a close friendship with the older man soon after he came to London. The two spent entire nights pacing the city, engaged in lengthy discussions of poetry and politics. Savage was probably born in London and probably in 1697, although the circumstances of his birth are as disputed as many of the rest of the details of his ramshackle life. (In later years, he became obsessively convinced that he was the bastard son of the Countess of Macclesfield, abandoned soon after his birth, and he pursued his alleged mother relentlessly in person and in print.) As a young man, he earned a precarious living by writing poetry and plays, some of which were staged at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. In 1727, Savage, always quarrelsome and short-tempered, became embroiled in a sword fight in a Charing Cross brothel and killed a man. Convicted of murder, but pardoned through the intercession of an aristocratic admirer, he entered a period of comparative fame and wealth, lauded for a long poem entitledThe Wanderer, but soon managed to sabotage his own good fortune and re-enter a world of poverty and exile from decent society.

Johnson’s words about his ill-fated friend could well be applied to thousands of bohemian souls as yet unborn when Savage died in 1743, a penniless debtor, in a prison in Bristol. The poet was abon vivantwho was never ‘the first of the company that desired to separate’. He was always short of cash and yet always prepared to spend other people’s. ‘It was the constant practice of Mr Savage to enter a tavern with any company that proposed it,’ Johnson wrote, ‘drink the most expensive wines with great profusion, and when the reckoning was demanded, to be without money.’ Like all bohemians past and present, he was an enemy of domesticity. ‘Being always accustomed to an irregular manner of life,’ his friend Johnson concluded, ‘he could not confine himself to any stated hours, or pay any regard to the rules of a family, but would prolong his conversation to midnight, without considering that business might require his friend’s application in the morning; and, when he had persuaded himself to retire to bed, was not, without equal difficulty, called up to dinner; it was therefore impossible to pay him any distinction without the entire subversion of all economy, a kind of establishment which, wherever he went, he always appeared ambitious to overthrow.’

Richard Savage : a romance of real life, Charles Whitehead, 1844

One of the areas through which Johnson and Savage regularly walked during their nocturnal perambulations was Covent Garden, which has some claims to being London’s first bohemian quarter. In the eighteenth century, it was a place of sexual freedom where prostitution flourished.Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies, first published in 1757 and updated annually for some years thereafter, listed the names, addresses, physical charms and sexual specialities of more than 100 women who worked as prostitutes in the area. ‘This accomplished nymph has just attained her eighteenth year,’ runs one typical entry, ‘and fraught with every perfection, enters a volunteer in the field of Venus. She plays on the pianoforte, sings, dances, and is mistress of every maneuver in the amorous contest that can enhance the coming pleasure.’ The poetically elevated language cannot ultimately disguise the basic financial transaction that is being advertised. The accomplished nymph’s entry in the list ends: ‘Her price, two pounds.’ Although it was published under the name of Jack Harris, a well-known pimp of the day,Harris’s Listwas almost certainly compiled by an archetypal inhabitant of Grub Street named Samuel Derrick. Derrick reputedly produced the first edition of the book and sold it to a publisher as a means of getting the money to release himself from debtors’ prison. For some time he was the lover of a well-known actress named Jane Lessingham and was considered something of a womaniser, although, as one unfriendly journalist wrote, ‘he was of a diminutive size, with reddish hair and a vacant countenance; and he required no small quantity of perfume to predominate over some odours that were not of the most fragrant kind.’

Covent Garden was also home to many of the era’s molly houses, meeting places for gay men. These were intended to be safe spaces in which they could dress and behave as they wished. A witness to a costume ball in one of the molly houses reported that, ‘The men were calling one another “my dear” and hugging, kissing and tickling each other as if they were a mixture of wanton males and females, and assuming effeminate voices and airs… Some were completely rigged in gowns, petticoats, headcloths, fine laced shoes, furbelowed scarves, and masks; some had riding hoods; some were dressed like milkmaids, others like shepherdesses…’ Of course, they were not always safe. The most notorious of the molly houses (which was actually in Holborn rather than Covent Garden) was Mother Clap’s and it gained its fame because of a raid on its premises in 1726. Forty men were arrested and, in a series of trials at the Old Bailey which followed, the ‘alternative lifestyle’ pursued by the ‘mollies’ was revealed. One witness, who had gone undercover at Mother Clap’s, described what he had seen: ‘I found near fifty men there, making love to one another as they called it. Sometimes they’d sit in one another’s laps, use their hands indecently, dance and make curtsies and mimic the Language of Women – “O Sir! - Pray Sir! - Dear Sir! Lord how can ye serve me so! - Ah ye little dear Toad!” Then they’d go by couples, into a room on the same floor to be married as they called it.’ It all sounds perfectly harmless, but the consequences, for some unlucky men, were terrible. As a result of the raid on Mother Clap’s and the series of trials that followed, at least three were hanged and others endured the ordeal of standing in the pillory.

Like Soho in years to come, Covent Garden in the eighteenth century was not just the prime London venue for illicit sex. The area also attracted artists and writers. Some, like JMW Turner, who was born in Maiden Lane, the son of a hairdresser, and continued to lodge in the neighbourhood during his early success as a painter, were famous; others were more obscure. Many of them were ferocious drinkers. Francis Hayman, who began his career as a scene painter in the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane and became a founding member of the Royal Academy in 1768, was a regular six-bottles-a-day man. One night, crossing Covent Garden Piazza with his friend, the actor James Quin, both men were so drunk that, when they fell into the gutter, they were unable to get out of it and had to wait for the night watchmen to haul them out. Figure and landscape painter John Hamilton Mortimer, another Covent Garden regular, made the mistake of eating a wine glass during one of his many drinking bouts – ‘of which act of folly he never recovered’, according to a contemporary. He died at the age of only 39 in 1779.

Nearby Soho also had its drunken and impoverished artists in these years. Samuel Collings, a caricaturist who was a friend of Thomas Rowlandson, died on the steps of a tavern while in his cups. Atrompe l’oeilpainter named Capitsoldi, probably an Italian who had moved to the city, was so penniless he couldn’t afford to furnish his lodgings in Warwick Street. Ingeniously, he ‘proceeded to paint chairs, pictures and window curtains on the walls of his sitting room… so admirably executed that, with an actual table and a couple of real chairs, he was able to entertain on occasion a friend in an apartment that appeared adequately furnished’. Some artists of the day suffered even worse fates than near destitution. The Swiss-born Théodore Gardelle murdered his landlady, a Mrs Anna King, in Leicester Square in 1761. He left her body lying in the house for several days, telling visitors that she was away in the West Country, but eventually had to undertake what theNewgate Calendarcalled ‘the horrid employment of cutting the body to pieces, and disposing of it in different places’. It was not an easy job. ‘The bowels he threw down the necessary,’ the anonymous author in theCalendarcontinued, ‘and the flesh of the body and limbs cut to pieces, he scattered about the cock-loft, where he supposed they would dry and perish without putrefaction’. He was wrong and his crime was eventually discovered more than a week after poor Mrs King had died. Gardelle was tried at the Old Bailey, found guilty and hanged in the Haymarket.

Romantics and Rebels

Nearly a decade after Richard Savage died in Bristol, another forerunner of English bohemianism was born in the same city. Thomas Chatterton was the son of a schoolmaster and musician who had died some months before the future poet arrived in the world on 20 November 1752. He and his mother and sister lived in genteel poverty near the medieval church of St Mary Redcliffe which became Chatterton’s favourite haunt as he grew up. Obsessed by the Middle Ages – or, at least, the version of them he created in his imagination – he began writing verse when still a child. He moved to London in 1770, already the author of a series of pseudo-archaic poems he had attributed to an imaginary, fifteenth-century monk named Thomas Rowley. His intention was to earn a living with his pen, but his poems and articles for the capital’s press did not bring in enough money to support him. He continued to write, but he was soon starving and desperate. In August 1770, after only a few months in London and still not 18 years old, he committed suicide by taking arsenic in the attic room he rented in Brooke Street, Holborn.

Chatterton made little impact on his contemporaries, but his short life and despairing death at his own hand had a powerful effect on generations to come. ‘The marvellous boy’, as Wordsworth called him, became an iconic figure in the Romantic imagination. Throughout the nineteenth century, perhaps most famously in the paintingThe Death of Chattertonby Henry Wallis (now in Tate Britain), he was depicted as the epitome of doomed bohemianism, a youthful genius fated to die in a garret, his brilliant talents unrecognised. (The model for Chatterton in Wallis’s painting was the poet and novelist George Meredith. Wallis later repaid Meredith by running off with his wife, providing the writer with material for his 1859 novelThe Ordeal of Richard Feverel, considered unspeakably shocking in its sexual frankness by its mid-Victorian audience. ‘I am tabooed from all decent drawing-room tables,’ Meredith wrote.) There was something about Chatterton’s death that was both appalling and inspiring to those aspiring to literary greatness. The attraction was not restricted to Britain. The novelist, poet and dramatist, Alfred de Vigny, a major figure in the French Romantic Movement, wrote a play about Chatterton which was very successful in the 1830s and formed the basis for a later opera by the Italian composer Ruggero Leoncavallo.

The Death of Chatterton, henry wallis, 1856

The first generation of English Romantics, admirers all of ‘the marvellous boy’, flirted with bohemianism themselves in their youth. Robert Southey and William Wordsworth, both of whom became Poet Laureate, exuded conservatism and respectability in later life, but were more adventurous as young men. Southey dreamed of utopia and planned, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, to establish an egalitarian community on the banks of the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. The dream soon foundered on the rocks of everyday practicalities and Southey’s growing realisation that he wouldn’t be able to employ servants to do the dirty work once he was in the New World. After a reduced plan to run a communal farm in Wales also came to nothing, Pantisocracy (as the two poets dubbed their political ideas) was abandoned. Wordsworth initially hailed the French Revolution (‘Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive/But to be young was very heaven,’ he later remembered), lived in France for some time and fathered a child with his French lover Annette Vallon. Southey’s fellow Pantisocrat Coleridge was later plunged into dissipation and despair by his addiction to opium.