Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Huia Publishers

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

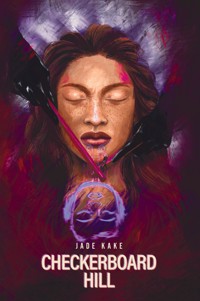

Checkerboard HilI is a story of belonging, dislocation, misunderstandings, identity and fractured relationships. When a family member dies in Australia, Ria flies from New Zealand and returns to the family and home in Australia she suddenly left decades before as a teenager. Waiting for her return are her husband and son in New Zealand. Neither family has met the other, and Ria has always kept her Māori, Australian, New Zealand identities and lives separate. But the family tensions, unfinished arguments, connections to places and meeting of former friends, lead Ria to revisit her memories and reflect on the social and cultural tensions and racism she experienced, and the decisions she made. The novel confronts the complexities of families, secrets and trauma and the way these play out across generations. It also explores the ways in which Māori cultural traditions and tikanga are transmuted and transformed across the Tasman, across time and space.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 372

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in 2023 by Huia Publishers39 Pipitea Street, PO Box 12280Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealandwww.huia.co.nz

ISBN 978-1-77550-808-3 (print)

ISBN 978-1-77550-799-4 (ebook)

Copyright © Jade Kake 2023

Cover image copyright © Rehua Wilson 2023

This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the prior permission of the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

Published with the support of the

Ebook conversion 2023 by meBooks

For my cousin Michael Main(30 November 1997–9 July 2020)

CHAPTER 1

Ria’s feet hit the ground with a soft steady thud. Her white trainers flick up crumbs of sandy soil. She runs without music, listening, listening to her breathing, the rasp of air pumping in and out as she tries to sync it with the rhythm of her muted feet. The dark scent of rotting leaf litter is everywhere. Her nostrils flare, pulling in the air. She passes under the canopy. The narrow path is in dappled shade. The pattern of light is similar to what she’s been trying to reproduce on canvas: a tremor of perpetual movement, a fragile temporality. Her eyes settle on a spray of clematis, white flowers bursting on a thin vine as it winds up the limbs of a young māhoe tree. She studies the splotchy pattern of the bark as she jogs past and makes a mental note to try it out in the studio. A litter of kawakawa lines the track. The leaves have been eaten away, leaving negative space.

She ducks underneath a branch without slowing. In her mind, she’s still in the studio. She works over the canvas, puzzling it out. The consistency of the paint isn’t right; it’s too viscous. Or the colour is wrong. What she wants is for the image in her mind to be made real. A neat transference. She only loves the messy bits after the work is done. Her calves start to ache as she jogs up steps of rough-cut timber and compacted earth. Her face is flushed. Her breathing intensifies as she gets higher. The fresh air pushes through her body, flushing out the paint and earth. She grits her teeth as she pushes forward and zigzags up the steep incline. A tūī calls out. The low murmur of waves rumbles in the distance, beneath the muffled sounds of the forest.

At the top of the steps, she skids to a halt. Drenched in a pool of light where the canopy opens to the sky, a wooden barrier has been erected across the path. Closed for maintenance. She pictures the track that skirts the cliff edge and plunges down to the beach, a path she’s jogged along countless times, her feet wearing deep grooves into the sand. She rolls her eyes. She glances around and darts through the gap between the sign and the bush. She breaks into a jog, then a run, and now she’s sprinting. She pushes hard as she busts through the break in the trees. Strands of native grasses whip her bare legs as she closes the final twenty metres to the top. A cloud of tiny seeds sticks to her legs. She’s exhilarated. She lets out a whoop as she reaches the summit.

The small bones in her back make a satisfying crackle as she flops down onto the hard ground. Her heart hammers, and her lungs feel stiff and full. The air feels good against her skin. Her mouth breaks open as a loud, blissful sigh escapes her. A small, hard tree root juts into her back and she squirms, trying to get comfortable. She peers up at the shifting sky. The clouds have an almost tactile quality, stretched out and brittle like candy floss, and she wonders how she can reproduce it with paint. Her skills as a painter have been honed through close observation of what is. She can’t look at things any more without perceiving a vast, vibrating field of infinitely varying colours that shudder and glisten and shimmer in the light. The light is the constant, the infinite variety of forms and textures drawn together by the consistent, unifying effects of the light. She yawns. It’s a lazy thought, barely formed, and she lets it drift away. Little bubbles pop and wriggle on the surface of her eyes. Then nothing. Her mind is bleached clean, clear and bright.

The sea crashes below, and the hum of bees fills the air. The sun sears, and as she closes her eyes against it, she’s enveloped in a warm yellow. The smell of salt and something else, faintly sweet and unidentifiable, meanders on the breeze. Cool air skims her face and her throat feels dry. She sits upright and gropes for her metal water bottle where it lies abandoned beside her. She unscrews the cap and gulps back water. It’s cool and slightly metallic. Droplets escape the edges and spill onto her shirt. She frowns and runs her thumb absently over the wet patch as it sinks into the light synthetic material and dissipates.

She gazes across the sea. The sun hovers somewhere above the horizon, and she takes a guess at the time—6.30 p.m., maybe? She doesn’t wear a watch, and her phone is in the car. She prefers to be unshackled from time here. Still, she pictures Ari and James. Ari sits on the couch and watches wrestling videos on YouTube. The sound is up too high. James sits at the table with his laptop open. A frothing glass of beer sits on a coaster next to him. He takes a sip and lets out a satisfied sigh. There’s froth on his upper lip, and he licks it off. His eyes dart back and forth across the screen.

‘You okay, tama?’ he calls out.

Ari turns and nods.

‘Turn the TV down a bit, okay?’

Ari nods again.

The image disperses with the sound of the waves crashing on the rocks below. The sunlight glints and sparkles on the crests. Each highlight is a sun in miniature. A few boats sit on the horizon, and they pass in and out of focus like an optical illusion. Another thought drifts into her mind, shadowy and formless, and she brushes it away with a slight shiver. It feels intrusive. It always seems to find her here. She presses her eyelids shut and wills herself to think of nothing: only the rhythm of the tide, the rhythm of her breathing, the cacophony of bird calls. She focuses on her breathing and wills her mind to remain empty, formless.

The sun sinks towards the sea. Her euphoria fades as blackness seeps into the sky. The ocean has turned choppy, dark and ominous. Fear creeps in at the edges, and something else, hollow and slippery. Her stomach gives a small growl, and for the first time she remembers that she hasn’t eaten since breakfast. She rises unsteadily, her legs stiff. She licks her lips and tastes salt. Her cooling skin is mottled with dried sweat, and she wriggles her body and tries to shake off the heavy feeling in her limbs. Slowly, her body grinds into motion and she descends in a sluggish jog that slips into a smoother gait.

When Ria reaches the carpark, she sees that her black SUV is the last one left in the lot. She pauses at the driver’s side door and gazes towards the horizon. Sea mist rises from the sand in the dim, slate light of dusk. Sweat gathers on her brow, and she rubs it away impatiently. She unscrews her water bottle and takes a swig. She swills the now lukewarm water around in her mouth and empties it, then swallows with a slight grimace. She puts her water bottle down beside the front tyre and stretches. Her muscles feel rubbery. She presses forward and pulses, shifting her weight onto her bent right leg and feeling the strain in her left calf. She pushes onto her toes and springs forward, sprinting through the dunes and out onto the sand. She closes her eyes, her face damp with sea mist and sweat. Chalky sand squeaks beneath her feet. She strips off her singlet and her shorts, then kicks off her shoes and discards them like sea litter. She bristles as the water skims her toes, the shock of the cold prising her eyes open. She recoils at it then lurches forward. She wades through the shallows and throws herself into the inky waves.

The water prickles her like thousands of needles. Beneath the waves, it pounds and churns around her ears, and everything is dark and cool. There’s no room for thoughts, only the harsh immediacy of the water. She gasps as she re-emerges into the crisp air of early evening, her head rising and bobbing above the waves. She feels the tug of the current and lets herself be dragged for a few moments, until she feels the edge of fear, razor thin and sharp like a knife. What if she just let go? She waits a moment longer before cutting against the rip and wading back towards shore. Her arms slice through the water in clear, firm arcs and drive her forward. She hauls herself out. Rivulets run from her shoulders as she sloshes into shore. At the line where the sea sheers away from the land, the tide drags over her feet. She wriggles her toes and buries them in the sand. She closes her eyes and draws in a deep breath. The smell of salt rises from her skin. She pads back towards the parking lot. The hard wet sand softens and gives way beneath her bare feet. She shakes her hair, heavy drops spinning onto the sand.

A handful of dry sand puffs out as she picks up her shorts and flicks them. She pauses and gazes out at the horizon. The colour is dazzling, making her gasp. She steps a leg through her shorts and then looks up again. The colour is shifting. The dying embers of the sun explode in a riot of colour, splashing against the bottoms of slender stratus clouds—salmon pink blends into sunset orange blends into soft lilac. She steps into the other leg of her shorts and pulls them up. They cling to her damp skin. She ties a loose bow in the draw-string as her eyes skate over the dunes. The breeze has left ripples at the dune’s edges, the sunset casting a warm crimson glow onto the blue-black sand. How are such extremes of the colour spectrum existing side by side without obvious contrast? Maybe it’s the yellow in the spindly grass that peeks through the sand that makes the blue seem so vivid. What is this sand, anyway, she wonders? She falls to her knees and grabs a handful, then splays her fingers beneath her nose. Translucent whites, pale silvers, oxide blacks. No, she corrects herself, it’s blue: so blue it’s almost black as it bleeds into the white. A memory hits her: blistering heat, bare skin scorched. It’s iron ore threaded through black sand! Her mind reels at the revelation, the possibilities for reproduction on canvas. She tilts her hand and the sand shifts again, evading easy definition. She feels a sigh escape her lips. It would be near impossible to try to capture this texture from memory. Maybe there’s a Ziploc bag inside the glove box? After a quick mental calculation, she shakes her head, sighs again and lets the sand slip through her fingers. She looks back to the sky, but it’s no longer there. The sunset has already begun to fade.

Back at the car, she fishes the key out of her pocket. She clicks the button and the car rumbles to life, a flash of warm yellow lighting up the interior. She climbs in, her body wet and slick like a seal. She kicks off her shoes, crusted with black sand, and throws them onto the floor of the passenger side. She opens the glove box and rifles through parking tickets, receipts and muesli bar wrappers until her fingers collide with the hard body of her phone. She presses the button and the lock screen flashes up. Three missed calls. She feels a flicker of annoyance, and her mood turns dark. Surely whatever it is can wait? She’s claustrophobic, like she’s in a small box and it’s getting smaller. She tosses her phone back into the centre console and starts the car. The stereo connects to the Bluetooth, and Tanerélle fills the cabin. The chords thrum through her chest and drown out the sea, her breathing, everything.

Pools of yellow light spill onto the sandy track, muted against the grey of dusk, deepening into the purple of night. The light is a hazy lilac-grey. The wash is like a diminishing waterfall, and the colour is broken and vibrating. It’s not static; nothing is. Like all colour it’s an illusion, a shimmering trick of the light. She imagines a thin wash of colour, paint derived from clay. She drives past the surf club and through the village. She passes the tiny houses embedded in the bank like lanterns as she winds up the hill and away from the ocean, towards the glow of the city. The moon rises overhead as she passes through the shadowy forest. She accelerates through the corners. She enjoys her car and how it smooths out the bends. Ria sings along, her voice a murmur beneath the ethereal sound of Tanerélle’s voice. She pushes her damp hair back. Her eyes gleam as she breathes out, heavy. She’s a person without a past, bleached clean like coral.

Ria pulls into the drive and parks next to James’s silver station wagon. She shuts down the engine, slips on her shoes and gathers her things as she climbs out of the car. The rotten steps sag beneath her. She stares at the door, clutching her keys.

From the back porch, she can see through to the kitchen. The light inside is warm. James stands at the bench, chopping something. A pot simmers. He turns towards the dining area, and she sees his face in profile. He says something. He smiles and laughs, showing his teeth. Ari leans over the bench. His loose curls spill over his face. He looks at James and giggles. His eyes sparkle, and dimples form. His smile is like Ria’s. It’s unfair, their casual ease with each other. She takes a deep breath as she twists the door handle.

James and Ari freeze like game animals. Their eyes pivot towards the door as it cracks open. James’s smile returns as he sees Ria, his face softening as he returns to the stove. She plasters on a bright smile as she steps into the light.

‘Māmā!’

Ari jumps off his stool and launches himself towards her, enveloping her in a warm hug. She wraps her arms around him and buries her face in his silky hair. Ari lingers and looks up at her through his dark lashes, his eyes shining and expectant. Ria kisses him on the cheek. James intercepts before Ari can start his endless chatter about his day—snippets he has saved up for her.

‘Ari, haere atu: shower time. Before kai. After dinner, I’ll read you a story.’

Ari disentangles himself. A pout forms on his small face as he marches down the hall towards the bathroom. Ria sets her things on the bench, and James pulls her into the kitchen for a quick hug. He frowns slightly at the touch of her cool face against his. She leans into him and inhales the cooking smells on his clothes.

‘Hey, love,’ James whispers. His breath is hot, and Ria feels something stir inside her. James pulls away and pours her a glass of red wine. He waggles his eyebrows as he passes it to her. Ari is singing in the shower. She takes a sip of her wine and tries to flatten the edges of her mouth as they creep up. Her eyes dart in the direction of the hall and return to James. He bites his lip and suppresses a smile too. She opens her mouth and a bleat of laughter escapes. She clamps her hand over her mouth. James’s eyes twinkle, and deep lines form at the edges.

The sound of the shower running falls silent.

‘Pāpā, homai tētahi tāora,’ Ari calls out.

James sighs as he walks down the hall.

Ria lifts the lid of the pot. It’s a curry of some kind; she’s not sure, but she recognises the bay leaves. She raises a second lid—steaming basmati rice. There’s a knob of ginger on top, and condensation pools on the inside of the lid. On the bench, the shape of a dish is discernible beneath a blue gingham tea towel. She pulls up the corner. Warm roti slathered with garlic. She spots other side dishes: a bowl of raita. Fresh coriander. The table is set, and there’s nothing left for Ria to do. She sits at the dining table, sips her wine and waits for James and Ari.

She looks at the photos lining the walls. Ari as a newborn, his tiny scrunched-up face and Ria’s pale, tired one. Ari at age four. His school photo from the previous year. Ari with his nana, James’s mum. Ria and James on their wedding day. James’s big, raucous family at their reunion three years ago. James and Ari at the beach: Ari holding the fish he caught with his pāpā, smiling, his small chest puffed out. There’s a photo of Ria with her mum and sister, wedged behind a photo of Ari. It’s small and out of focus. Ria is young: it was taken before James, before Ari. There’s Ria at her marae. She’s alone, standing beneath the tomokanga. She hasn’t been back since. Something hard and tight pinches inside.

The photographs are punctuated with taonga. The carved taiaha James received for his twenty-first birthday. A kete woven by James’s sister. A heru that belonged to James’s grandmother. A prized piece of pounamu gifted to Ari by James’s whānau. A piece of whalebone—half-carved, unfinished, inherited from her koro—is Ria’s sole contribution, and the taonga feels lonely, out of place. A painting of an abstract landscape hangs above the mantelpiece. The brushstrokes are naïve, and the colour is flat, lacking in depth. The hue is turgid, too similar in both the light and the shadow. Ria feels faintly embarrassed by it. A flicker of a memory dislodges and rises to the surface: the grit of silty clay between her fingers, ripples of light cutting through warm, murky water.

Ari and James burst into the room, into life, and she’s jolted out of her memories. James methodically shifts the pots from the stove to the table. Ari takes his usual place opposite Ria and beside James. As they sit to eat, James nudges Ari.

‘Go on, tama. Like you learnt at kura.’

Ari looks small and serious as he recites the karakia. ‘Nau mai e ngā hua …’

Ria looks down and follows along in a gentle murmur, feeling grateful as she says ‘Tāiki e’ at the end of the prayer.

‘Ka pai, tama,’ says James as he reaches over to pull off the lids.

James serves Ari first, then Ria and then himself, filling their plates with rice and curry. Ria and Ari take turns sprinkling and spooning toppings over the kai. Ria loads her fork and looks at James. He feels her watching him and looks up, the dark pools of his eyes boring into hers. She looks away. What does he see there? What dim shapes rise to the surface? He stares at her for a moment too long. She squirms, and he looks away.

After dinner, she showers, scrubbing the salt away. James has set out a clean towel, and she wraps herself in it, feeling the soft fuzz against her bare skin. She drops the towel and steps into her worn cotton pyjama pants. She pulls an old T-shirt over her head. She slides her fingers down her hair and squeezes out the remaining droplets of water. She lets the water drip onto the worn timber floor. The damp strands graze her shoulders. She flosses and brushes her teeth.

When she enters the bedroom, she sees that James has turned down the cover on her side of the bed. She climbs in. The sheets smell fresh and clean. She sinks her head into the soft down pillow and rolls onto her side. She can hear James reading to Ari in the next room. She chuckles as he puts on different voices for each of the characters in Ari’s story. A squeal of laughter rings out.

The story ends. She hears the patter of footsteps and a tap on the door. The door opens and Ari’s small face peers through the gap. Ria beckons him with a smile, and he tumbles through the door like a puppy. She opens the duvet and Ari buries himself under the covers. She presses his warm, small body against hers and breathes in his scent. She closes her eyes, teetering on the edge of wakefulness and sleep, and falls into a warm slumber.

When she wakes up, Ari is gone, and the room is dark. James snores gently. The clock displays a blur of bright red numbers in the darkness. 3.11 a.m. She gets out of bed, slipping out of the door that they keep half-open in case Ari has nightmares. She peeks into Ari’s room. She can just make out the shape of his body: he’s sleeping curled up with his arms wrapped around himself. Moonlight floods the kitchen, and she notices the dishes have been washed and cleared away, and everything is clean and clear and perfect.

Sunlight streams through the blinds. Ria feels groggy and doesn’t know where she is. Someone raps on the door, and she sinks back in relief at the familiar sound. It’s James. He carries two mugs of coffee. He pushes the door shut and waits for the click. He sets one of the mugs on the bedside table, then swivels and hands the other one to Ria as he wedges a pillow behind her. She leans back and takes a sip of the coffee. It tastes great, and she moans with pleasure. She sets her mug down and brushes James’s lips with hers.

‘Mōrena, ātaahua,’ James says, biting his lip.

‘Morning.’ She pulls him towards her and slips her tongue between his teeth. He slides his hands underneath her shirt and grazes her nipples, before moving his hands around her back. She’s hot with anticipation, waiting for James to tug her shirt over her head, when the alarm blares into the moment.

‘Shit,’ James curses. ‘Sorry, babe; I’ve got to get ready for mahi.’

Ria kisses him again. She slides her tongue between his lips, seeing if she can tempt him. He kisses her back and pulls away. When she opens her eyes, he’s up and dressing. She watches as he steps into his stiff work pants and threads a leather belt through the loops.

‘Where’s Ari?’ she asks as he pulls on a dress shirt and straightens the starched collar.

‘He was having breakfast when I was making us coffee,’ James responds, as he pulls his tie from the open wardrobe door. He loops it around his neck and tucks it under his collar. ‘So he should be washing his face and brushing his teeth by now.’

James looks into the mirror on the inside of the closet door, his eyebrows furrowed. Ria watches his reflection as he wraps his tie into a Windsor knot.

‘But I’d better go check on him. You know how sometimes he gets lost in his own thoughts. Like his māmā.’ He kisses her on the forehead and walks out of the room.

Ria slides her feet into her slippers. She picks up her coffee and wanders through the hall and into the kitchen. Ari sits at the table, wearing his school uniform. He’s reading something and frowning. She leans against the door frame. ‘Ata mārie,’ she says.

‘Morning, Māmā,’ Ari responds without looking up.

She walks up to him and slings her arms around his shoulders. She rests her chin on his left shoulder. ‘What are you reading? You looked so serious just now.’

‘It’s from kura. Whaea Mere gave it to me for homework,’ Ari says. He screws up his face and lets out an exaggerated sigh. ‘But I keep getting my words mixed up, Mum.’

‘Can I help?’ Ria asks.

Ari shakes his head. ‘Kāhore, Māmā. It’s okay. Pāpā can help.’

Ria frowns. ‘Okay. Ka pai, tama.’

‘Ari!’ James’s voice reverberates down the hall. ‘Time to wash your face and brush your teeth.’

Ari puts down his book and climbs off his chair. He marches to the bathroom, his limbs floppy. The placemat is splattered with milk, an empty bowl of Weet-Bix pushed to the side. She picks up the book, which Ari has laid face-down clear of the milk, and flicks through the pages. She picks a page at random and puzzles through the text in te reo. There’s no English translation, and the illustrations are scarce, unhelpful. When did his reading become so advanced? She screws up her face as she tries to piece together a sentence, picking out the kupu she knows and trying to match the unfamiliar and semi-familiar words with the images that shuffle through her mind. James and Ari are talking in the bathroom, in te reo too, the way they do when she’s not around, and those kupu trickle down the hall and into her ears. They’re speaking too quickly; she can’t translate fast enough to catch their meaning, though isolated words pop and swim, bold in her mind.

When James and Ari come into the kitchen, they’re both fresh and shining. Ria gulps the rest of her coffee. She’ll make a fresh pot once James and Ari leave.

‘He aha tōu mahi i tēnei rā?’ Ria asks, her voice shaky.

Ari looks to his dad before turning to her. ‘We’re learning about native spiders and insects in Matua Rawiri’s class. Did you know there are twenty-five hundred types of spiders native to New Zealand, and only three of them are venomous?’

Ria nods, urging him to go on.

‘And? What else?’ James prompts.

Ari nods, and his body shakes with excitement. ‘And Katene’s dad’s going to teach us mau rākau.’

‘Don’t worry,’ James says to Ria. ‘It’s just a demonstration, Ari knows he’s not allowed to enrol until he turns—’ James breaks off and turns to Ari. ‘How old, tama?’

‘Ten,’ Ari responds glumly.

‘Āe,’ says James. He glances at his watch, gulps down the dregs of his coffee and puts the mug down on the bench. ‘Whoops! Time to go.’

Ria crouches and hugs Ari goodbye, and he hugs her back, a quick press into her body, and then runs out the door, impatient for the day to come.

James moves past Ria into the kitchen. He pours some coffee into a mug and pushes it into the microwave. As he waits for it to heat, he leans into her. His cheek grazes hers, and the smell of aftershave surrounds her. He smells good, and a wave of desire passes through her like a fever. Then the microwave dings, and he decants the steamy coffee into a travel cup and grabs his keys off the bench. He picks up Ari’s backpack, slings his own satchel bag over his shoulder and turns to follow Ari out the door. Then he pauses, as though he’s forgotten something, and Ria wraps her arms around his waist, pressing her nose into his back. He turns to face her and kisses her softly.

‘Love you,’ he says, his face close to hers, the smell of coffee on his breath. ‘Kia pai tō rā e ipo.’

Ria bites her lip. ‘Bye, love,’ she says to James’s back as he saunters down the steps to the car.

She stands on the back steps and watches them leave. The scent of James lingers, but the heat of his body has already dissipated. The open sky makes her feel brittle and exposed, and she wraps her arms tightly around herself before walking back into the house.

The door creaks and closes behind her with a click. The old house smells faintly musty. Light filters in through the kitchen window, illuminating a cloud of dust. The sound of the clock ticking fills the room. Finally alone, Ria feels something inside her drop and soften. She never knows she’s been on edge until the tension has fallen away.

The scent of coffee fills the room as she sips from her second steaming mug. She sits down in Ari’s place at the table and drags her laptop closer, wiping away milk streaks with her thumb. She takes a bite of her toast, thick and grainy, with butter soaked through and peanut butter on top. One of her oily fingers greases the trackpad. The computer is taking its time to wake up. She examines her breakfast. In theory, the toast and peanut butter should be the same consistent, even-brown colour, but the oil in the topping is slick, reflecting the morning sun and lace curtains. The computer wakes to her inbox, and she frowns at the subject lines, barely reading them. Her coffee needs more milk. She grasps the handle of the fridge. Ari’s artwork plasters its door, held in place by magnets and arranged at random. The artwork is peppered with pānui from his school, and she pauses to read one before opening the fridge to retrieve a carton of oat milk.

She sips her coffee and answers a few emails. An invitation to speak at an event. A reminder of a grant application due in a few days. An email from her dealer updating her on the sales from her recent show. An email from the curator of a public gallery that owns a number of her works, notifying her of a request from a government department to purchase her work. The painting will hang in the foyer of a building. The large-scale works require a bigger studio, or to be painted in situ—she hasn’t done many of these. This one was completed on residency: they gave her a warehouse space in the Waitākere Ranges to work from, as well as a generous stipend. The painting is twelve by six metres and in portrait format, which is unusual for her. Her work is mostly landscape. It took her four weeks of painting full-time to complete, and she had to use a scissor lift to do it. She’s not sure how they’ll get it into the building—a crane, maybe?

She takes small, absent bites of her toast. She checks her personal email—a note from Ari’s school, which she deletes without opening. James will handle it, or else has already handled it. She closes her laptop. The chair scrapes the floor as she pushes back and propels herself away from the table. She leaves the remains of her toast on the table, half eaten, forgotten.

She wanders down the hall and into the bedroom. Her movements are brusque as she dresses in loose pants and a soft cotton T-shirt. She crosses the hall into the bathroom and looks at herself in the mirror. Her work clothes are almost identical to her sleep clothes. At least they’re clean. She pushes her short wavy hair back and ties it at the base of her neck. She washes her face and brushes her teeth. She spits, baring her teeth and revealing pink gums. She examines her face for a moment: pale skin, a smattering of dark freckles, hazel grey eyes. She frowns and rubs at the dark circles underneath.

In the kitchen, she refills her cup and heads towards the door. She steps over the threshold. From the back porch, she sees an elderly Pākehā woman, her neighbour, standing in their shared driveway. Her hair is a cloud of white, and her loose dress billows in the wind. Ria waves.

‘Kia ora,’ she calls out, keeping her voice bright.

The woman stares at Ria for a few moments before turning and toddling away. As Ria closes the door behind her she finds a note, handwritten on yellow lined paper, the edge lifting up in the breeze. Spidery letters spill across the page: ‘Hello. Please consider others and keep your yard TIDY. Next time we will have no choice but to report you to Council.’

Ria looks over the yard. The lawns have been clipped and the edges trimmed. The garden hose is coiled, mounted on the wall next to the tap, and without looking she knows the pots, bags of potting mixture, loose pavers and garden implements mounted on the walls of the locked potting shed are all in order. The only signs of disorder are a bike—Ari’s—lying on the grass, and a lone basketball on the concrete drive.

Ria rolls her eyes, and then grits her teeth and rips the note off the door. She crumples the paper into a tight ball in her fist and tosses it over the handrail and into the open wheelie bin. She clomps down the steps. She feels someone watching her over the fence and keeps her eyes forward. She won’t mention this to James. It’s better if he doesn’t know. Sometimes she can’t deal with his gentle concern, his patient explanations and endless excuses for other people; his willing the world to be different to the way it is. Wake up! She wants to scream it in his face. But she won’t do it. She never does.

Her hand trembles as she crosses the yard and walks towards her studio. Droplets of coffee spill onto the concrete and leave dark grey splotches, like a Rorschach pattern.

She opens the door to the studio. The room is unlined, the back of the timber weatherboards visible beneath the exposed studs, nogs and cross bracing. On winter mornings, her breath fogs the air, mingling with the steam of her coffee. Today, the weather is crisp but not cold, and she leaves the electric heater switched off. Blank canvases and unfinished paintings line the walls. The air feels cool and earthy. She closes her eyes; breathes in the pungent smell of cedar. She surveys the familiar space. Her paint and tools are lined up and each item is in its place. She walks around the edges of the room and opens the windows to let the air circulate. She turns on the radio, permanently tuned to Radio New Zealand Concert, her daily ritual as she readies herself for work.

A new canvas, which she prepped the day before, waits on the easel at the centre of the room. The smell of gesso fills the air as she primes it. As the gesso dries, she prepares the oil colours. She prefers to make her own paint, combining the oil and raw pigment to create the right shade and consistency. She doesn’t name the colours she mixes, resisting easy categorisation. She believes that the naming of seen colour desensitises and diminishes her powers of perception.

She works the canvas in layers. She draws a guide in pencil, followed by a base layer of oil paint and a super layer. In her last series, she used oil pastel. In her new works, for her upcoming solo show, she has been experimenting with natural pigments, using clays, sands and crushed rocks. From the whenua; from Papatūānuku. With each new attempt, she learns the limits and boundaries of the material, of herself. She enjoys the failures and the successes: finding the boundaries, the edges of what’s possible.

The catalogue from her most recent show is fanned out on her desk. Her work has been captured by the photographer’s expert eye. The text is bilingual: te reo Māori and te reo Pākehā, approved by her and written with a fluency she does not possess. It has been translated from her own original text, written in English and peppered with kupu Māori. She picks up the catalogue now and turns it over, remembering the opening. Ria did a short mihi to the gathered crowd, and she spoke with confidence, thanks to James’s patient coaching. She enunciated each syllable without errors before breaking into English.

After the applause died and a hubbub of conversation rippled through the room, a Pākehā woman, the owner of a well-known private gallery in the city, approached her. Ria’s eyes flashed with fear as the woman attempted to talk to her in te reo. The woman’s face was animated as she spoke. Ria struggled to hear the sounds, and her tongue was heavy. James walked over and interrupted the woman.

‘Aroha mai—can I borrow my wife?’

He whisked her away, out onto the balcony and out of sight, and she leaned into him, her face burning.

‘I—I didn’t mean to freeze like that,’ Ria stammered. She felt frustrated with herself; foolish at the pride she had in her catalogue text, her brief mihi. ‘She caught me off guard. I knew what she was saying but I panicked. I—I wasn’t expecting that from her.’

James enveloped her in a hug, crushing her small body into his larger one. She submitted, her heart flapping like the wings of a tīrairaka. She pressed her ear to his chest. His heartbeat was slow, steady. She looked up at him and attempted a small smile to show her gratitude. When he looked away, she allowed the smile to die on her lips.

Safe in her studio, Ria works between two canvases, and sketches her ideas for a third. She gets lost in her work, and by the time she re-emerges, the sun is high in the sky. She breaks for lunch and returns to the house. Before James, before Ari, she could work all day, forgetting to eat or rest. Her body felt ephemeral, impermanent, then. James’s fussy prepared lunches and gentle reminders impose a sense of order, of necessary restriction, and she submits to his care. She follows his instructions as she follows the guidelines she draws onto her canvas. It’s easier this way; it’s easier to let go and just accept things.

Inside the kitchen, she pulls a Tupperware container out of the fridge. James prepares the family’s lunches for the week ahead every Sunday, and although she protests weakly, she accepts it.

She warms her lunch in the microwave and then walks outside to sit on the back steps, eating directly out of the container like a hungry wolf. It’s really good. It’s hard to hold onto small slights when he makes food like this. Sated, she drops the container onto the step and closes her eyes for a moment, feeling the warmth of the sun.

She gazes out over the garden, and is surprised by the showing of purple and red flowers. She never remembers any build-up, is forever missing the signs, and the appearance of the bold blooms feels sudden and unexpected.

She rises to her feet and goes back into the house. She tosses the empty container in the sink without rinsing it and returns to her studio, where she’ll stay and work until Ari and James return. As she crosses the yard for the second time that day, she notices that although the sky is mostly blue and white, light grey clouds are gathering near the horizon and threatening rain.

Three shrill chirps ring out from the blue Formica telephone mounted on the wall of the studio. Ria’s skin prickles at the sound.

She looks up from her canvas and sucks in a deep breath, then waits a moment before she exhales and walks across the black and white checked linoleum floor. There’s a fine layer of dust on the surface of the phone. She never gives out this number; doesn’t want people to call. It was installed at James’s insistence.

She picks up the receiver. ‘Kia ora,’ she breathes into the mouthpiece.

She wedges the handset between her ear and her shoulder. A dull flat tone rings through her ears as she waits for the person on the other end to speak. The patter of rain on the studio roof is audible beneath the static, and the window is now foggy with condensation. The scattered light through the overcast sky casts softly edged shadows. The kōwhai tree outside her window sways in the wind, heavy with yellow blooms. A tīrairaka flits against the glass. The bird dips, and Ria worries it will fly through the open window. It changes course at the last minute and disappears.

There’s a click, followed by a muffled sound.

After another slight pause, the voice on the other end of the line speaks.

After the call, Ria sets down the receiver, crosses the room and sits on her stool. She doesn’t pick up her brush. She sits there for a long time, the paint congealing on her palette. The sky through the window darkens, and lights from the neighbouring houses begin to twinkle through the trees.

There’s the sound of a car in the driveway, the flash of lights and, as if by clockwork, Ria springs into motion. Her limbs are rigid as she walks over to the house. James looks up as she opens the door, surprised. His satchel is on the floor and his keys are on the kitchen bench. He’s still wearing his work clothes, and his jacket is draped over the back of a dining chair.

‘I thought you must have gone for a run. Have you been in your studio this whole time?’

Ria doesn’t answer and stands still in the doorway.

James walks over to the fridge and pulls out a beer, cracking the top and pouring it into a glass.

‘Ari’s at soccer practice. Kathy—you know her girl Te Āniwaniwa—said she’d feed the kids afterwards and get them ready for school tomorrow. Ari’s sleeping over.’

James pauses. ‘I did text you—’ he says, as his eyes dart to Ria’s phone, which has sat on the dining room table since breakfast.

‘I’m sorry I didn’t wait for you to get back to me, but when you didn’t text back, I just figured you wouldn’t mind. But I told Kathy to call us if he wants to come home.’

James picks up his phone and flicks through an app as he takes small sips of his beer. ‘I was thinking of getting takeaways. What do you feel like? I was thinking pizza.’ Silence. It takes James a moment to notice Ria hasn’t responded.

They sit and listen to the hum of the car engine.

‘We’ll come with you. I’ll book a flight for tomorrow. I’ll let work know, and Ari’s school.’

Ria shakes her head, slight but firm. ‘No, it’s all right. I don’t want Ari missing school, and I know you have that important presentation coming up.’

James stares at her for a moment, uncomprehending. Ria feels his unspoken questions; they hit against that hard and steely part of her.

As they arrive at Auckland Airport, she asks James to drop her off. He insists on parking; on paying the exorbitant fee and accompanying her to the gate. He presses the button at the entry gate and takes the card. Other times, Ria would protest, and she knows James expects her to. This time, she accepts; she lets her body slump like a sack in the passenger seat as she gazes out the window.

The barrier lifts, and they enter the short-term carpark and circle the lot. They find an empty space. James kills the engine. He reaches down and pulls the lever to pop open the boot. He walks around and pulls her suitcase out of the back of the car. He grips her hand tightly as he wheels her suitcase across the parking lot and towards the terminal.

‘You’ll only be allowed as far as security,’ Ria reminds James, as though she’s just remembered herself. She sees his face soften slightly. He seems reassured that she’s spoken to him at all, and Ria feels something harden in her gut in response.

She checks herself in at the kiosk and scans her passport as James tags her bag, scans it and deposits it at the automated bag drop. They ride the escalator to the upper level. At the entry to the security screening, she fills out the departure card and tucks it inside her passport. She pretends to rummage in her bag for something, and then reconsiders, giving up the pretence.

‘You should go,’ she says plainly.

James looks pained and says again, ‘Please, let us come with you.’

‘I’ll be getting in late, so I won’t call you tonight, but I’ll call tomorrow, okay?’ She looks down, avoiding his gaze.

‘Okay,’ James says, his face creased with worry.

A call cuts through the silence.

‘Flight NZ187 to the Gold Coast will soon be boarding. Passengers are asked to go through security and directly to the gate.’

‘I have to go,’ she says.