Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

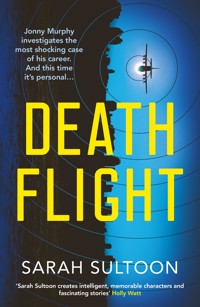

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: The Jonny Murphy files

- Sprache: Englisch

Cub reporter Jonny Murphy is in Buenos Aires interviewing families of victims of Argentina's Dirty War, when a headless torso has washed up on a city beach, thrusting him into a shocking investigation… `Jarringly authentic, pulsatingly engrossing, granular frontline reporter's eye – her finest thriller yet´Peter Hain `A tense political thriller that veritably thrums with menace. Clever, ambitious and utterly compulsive´ Kia Abdullah `Gripping, intriguing, action-packed and powerful, I raced through this hard-hitting thriller in just two days! ´ Philippa East _______________ Argentina. 1998. Human remains are found on a beach on the outskirts of Buenos Aires – a gruesome echo of when the tide brought home dozens of mutilated bodies thrown from planes during Argentina's Dirty War. Flights of death, with passengers known as the Disappeared. International Tribune reporter Jonny Murphy is in Buenos Aires interviewing families of the missing, desperate to keep their memory alive, when the corpse turns up. His investigations with his companion, freelance photographer Paloma Glenn, have barely started when Argentina's simmering financial crisis explodes around them. As the fabric of society starts to disintegrate and Argentine cities burn around them, Jonny and Paloma are suddenly thrust centre stage, fighting to secure both their jobs and their livelihoods. But Jonny is also fighting something else, an echo from his own past that he'll never shake, and as it catches up with him and Paloma, he must make choices that will endanger everything he knows… _______________ `Sarah Sultoon creates intelligent, memorable characters and fascinating stories´ Holly Watt `A powerhouse writer´ Jo Spain `A must-read, high-octane political thriller that does not let up … a heart-stopping and deeply touching read. Superb´ Eve Smith `With Argentina back in the headlines, this is a timely thriller exploring one of the darkest chapters in the country's history … a gripping read´ Martin Patience, BBC News `Non-stop, breathless, harrowing, who-can-we-trust thriller, all the more powerful for being based on real tragic events´ Anthony Dunford Praise for Sarah Sultoon **Longlisted for the John Creasey (New Blood) Dagger** **WINNER of the Crime Fiction Lover Debut Thriller Award** `A first-class political thriller´ Steve Cavanagh `A bitingly sharp, pacy thriller. Devilishly good. I inhaled it´ Freya Berry `A brave and thought-provoking debut novel´ Adam Hamdy `A taut and thought-provoking book that's all the more unnerving for how much it echoes the headlines in real life´ CultureFly `A tense thriller, a remarkable debut, heartbreaking, but ultimately this is a story of resilience and survival´ NB Magazine `A powerful, compelling read that doesn't shy away from some upsetting truths … written with such energy´ Fanny Blake `A powerful story of the brutality of front-line journalism. Authentic, provocative and terrifyingly relevant´ Will Carver `An extraordinary piece of writing from a political thriller writer at the very top of her game´ Victoria Selman `Brilliant and gripping´ S J Watson `Full of danger and pulsating characters´ Louise Beech

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 359

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iArgentina. 1998. Human remains are found on a beach on the outskirts of Buenos Aires – a gruesome echo of when the tide brought home dozens of mutilated bodies thrown from planes during Argentina’s Dirty War. Flights of death, with passengers known as the Disappeared.

International Tribune reporter Jonny Murphy is in Buenos Aires interviewing families of the missing, desperate to keep their memory alive, when the corpse turns up. His investigations with his companion, freelance photographer Paloma Glenn, have barely started when Argentina’s simmering financial crisis explodes around them.

As the fabric of society starts to disintegrate and Argentine cities burn around them, Jonny and Paloma are suddenly thrust centre stage, fighting to secure both their jobs and their livelihoods.

But Jonny is also fighting something else, an echo from his own past that he’ll never shake, and as it catches up with him and Paloma, he must make choices that will endanger everything he knows…

DEATH FLIGHT

Sarah Sultoon

vTo my parents, who are always there. And to Noa, Emma and Clare.vi

Contents

Prologue

La Plata, Argentina November 1998

The body was almost invisible at first, the same colour as the dawn sea, nudged up the wide sands by the gentle swell of the water. Was it blue, grey or white? That it was a curious combination of all three hardly mattered once it became obvious what it actually was.

A female torso. Bloated and headless. Only identifiable as a torso because it still had arms, even if the hands on the ends were missing their fingers. Ragged stumps where there had once been legs, sawn off rather than sewn up, no doubt as to how brutally they’d been removed. No identifying marks save the faded outline of a tattoo over the long-silenced heart.

The men looking on all appeared the same at first, too. Smudged fatigues, tall jackboots, flat caps. Four military officers marching in step along the deserted beach, any differences between them as camouflaged as their uniforms. Only when they paused to regard the water’s edge did any variations in their posture emerge. Was one standing prouder than the next, or was it that another was recoiling? Suddenly, they didn’t seem aligned at all.

The coast wind was blowing hard enough to whip away any sharp intakes of breath. The early-morning light was still murky enough to justify any squinting and blinking in disbelief. But nothing could justify the orders and instructions that followed, centred on one man in particular, who was hunching lower and 2lower as if to hide his shame. The only voices crying foul were those of the seagulls, wailing as they circled in the clouds overhead.

Could the Flights of Death have joined these birds in the skies once again? The abominable legacy of Argentina’s Dirty War, supposedly ended fifteen years earlier, a military repression unprecedented in scale. Planes loaded with human cargo. Thousands of shackled prisoners disposed of mid-air. Dead bodies destined to disappear forever in the icy depths of the sea. It was only thanks to the inescapable rhythm of the tides that some remains were ever found. But the former military regime was yet to be fully brought to justice.

Only when the jackboots finally marched away did the gulls swoop and feast. But by then there was little left to enjoy.

Chapter One

Buenos Aires, Argentina Two Weeks Later

His coffee cup rattles in its saucer as the dancers spin. Thick white china, too small for its earthy measure of espresso – a cortado, they call it, bigger than its Italian cousin; no, better, the Argentinians insist, always with a knowing wink, despite the fact they’re yet to manufacture a satisfactory cup to put it in. Another aromatic splash trembles over the brim but Jonny Murphy is miles away, transfixed by the couple whirling across the cobblestones directly in front of his table. Beyond, the candy-striped corrugated-iron houses that distinguish the Buenos Aires district of La Boca from anywhere else in the world shimmer in the afternoon sun, blocks of colour popping between the dancers with every clack of their patent heels. Half his coffee is pooled in the saucer by the time the performance ends, still Jonny stands to applaud, an appreciatory ripple through the jacaranda trees dripping blossom overhead.

Street tango. This most-famed symbol of Argentinian culture was forced underground during military rule along with all forms of artistic and intellectual expression. It’s a moment of joyous abandon every time it reclaims its rightful place even fifteen years later. And Jonny Murphy has a whole lot of time for moments like these. He’s still clapping long after his companion has sat down.

‘Shall I get you another one?’ Paloma arches an eyebrow at his spilled coffee.

Jonny frowns as he notices the thick black camera strap still slung undisturbed over the back of her folding chair.

4‘You didn’t take any pictures? How could you not?’

She regards him from under a pair of heavy black eyelashes. ‘Since when do you think we are going to earn any money from a lifestyle feature?’

‘Since when are we going to earn any money, full stop,’ Jonny mumbles, staring down the lane, brightly coloured little houses blurring into one. They both work in news – he’s a reporter, she’s a photographer – but they are struggling even when they join forces. The currency of freelance journalism is ephemeral at the best of times, but with Argentina’s economy rapidly tipping into decline, it is fast becoming as devalued as the peso.

Paloma sighs, snapping open her battered tin of blonde leaf. ‘Ironic, isn’t it? We can barely cover our costs even when we’re covering a financial crisis.’

‘Not sure that’s entirely ironic.’ Jonny shoves his chair back under their table a little too hard. ‘Unlike the fact that everyone on the newsdesk apparently has the memory of a fucking goldfish. I still have to explain almost every word I file on the bloody thing. What don’t they understand? Debt is astronomic, inflation is off the chart, it’s only thanks to the International Monetary Fund that the financial system is still functioning, and I haven’t even got started on unemployment. “Follow the money” is all I’ve been told to do since I got here and that was almost a year ago. Even the newsdesk interns should get the basics by now.’

‘It’s all those big words you’re using,’ Paloma replies with a grin. ‘“The International Tribune’s Jonny Murphy” is quite a mouthful, too.’

Jonny despairs at the blush instantly heating up his neck. ‘Well, then the desk should try giving me more than three column inches to explain it in. Sometimes I think it would be easier if I was filing for a daily rag.’

‘It would be a thousand times worse, is the truth. You’re lucky to have the backing of a major international newspaper. We 5wouldn’t stand a chance with any of the other stories we pitch otherwise. You’re not just some nobody from New Mexico with bleak pictures of deserts in her portfolio. You’ve got an international profile. You can make a case for investigating something other than the financial crisis once in a while, even without a lead.’

Jonny sighs, even as his heart rate ticks up at the mention of their lead. The Trib may be the most widely circulated English-language newspaper in the world. But the truth is his profile is nowhere near high enough to warrant the kind of trust and investment this particular lead is going to need. He’s spent most of his two years as a reporter trying to reinvent himself after his first journalism gig in the Middle East came to an abrupt end. He only got that gig in the first place courtesy of his fluent Hebrew – his Israeli single mother still insisted on speaking it at home long after they moved to the UK when he was a baby. As for Paloma – she has way more experience of Buenos Aires than he does, but is still scraping together a living off the back of flogging the odd good shot. The fact that she speaks the language this time is more use to him than it is to her. She doesn’t need to speak to shoot.

He looks pointedly at her camera. ‘Well we haven’t got enough to actually pitch anything yet. Let alone successfully.’

Paloma’s cigarette sparks with a hiss. ‘And wasting a roll of film on pavement tango isn’t going to help with that.’

Disheartened, Jonny waves for the bill rather than reply. He knows no journalist is stationed in Buenos Aires these days for the beauty shots. And he and Paloma are secretly looking into a far uglier matter. It’s been fifteen years since Argentina broke free from a military dictatorship so brutal it went to unimaginable lengths to hide the evidence of its crimes. Lengths that have, so far, made it impossible to assemble enough proof to bring justice to bear, despite the growing clamour from politicians, journalists and human-rights groups the world over. The Dirty War, the 6repression was called, so named for the scale of its depravity. Jonny eyes the two burly men banked in a nearby doorway, arms folded, eyes darting around until the small packages openly changing hands in front of them are safely stowed and the scooter paused conspicuously ahead fires up and zooms away. Is it any wonder that former military commanders are still free to mix in Argentinian society regardless of accusations so horrific the details are almost unprintable? This exhibitionist city – its riotous colours, its intoxicating smells, its raucous and infectious energy – just demands to be seen. Even its underbelly operates in plain sight.

He drops a couple of crumpled banknotes on the table. ‘I need to get back if we’re going to have a chance of following up any leads tomorrow. There’s loads more phone calls that I still need to make.’

There go those eyelashes again. Jonny briefly wonders if Paloma can actually see anything properly with them hanging in the way. She probably wouldn’t bother looking so hard if she could.

‘Fine. So let’s go. But you don’t get another coffee.’

Jonny tries not to watch her readying to leave. Paloma seems to be able to make even the simplest of tasks look elegant and sophisticated.

‘I’ve got some sausages back at the ranch instead if you’re interested,’ he adds hopefully. ‘My calls will only take a few minutes.’

‘Thanks but I didn’t realise it was so late. My film should be ready by now. The technician said twenty-four hours on the nose. If I hurry I can make it before the shop closes.’

Jonny brightens at the prospect, looking up. ‘So bring it over afterwards, if you want. It’ll help with working out what to do next if we can go through the pictures together.’

Paloma shakes her head, slinging the camera strap firmly around her body. Jonny commands his gaze away from how it cleaves across her chest.

7‘You know how I hate having someone ogling over my shoulder. I’ll call you later, when I’ve had a chance to look. You can fill me in on the plan for tomorrow then too.’

Ogling? Jonny fixes his gaze on the pavement as he musters up a weak nod. He’d settle for enough money shots on that roll of film to give their investigation some momentum.

‘Oh, and …’ She pauses. ‘Sausages?’

‘I meant choripanes,’ he replies lamely, regretting having mentioned them. ‘You know, the ones like chorizo hot dogs —’

‘My favourite,’ Paloma interrupts archly. ‘Save them for tomorrow, OK? Who knows, we might have something to actually celebrate then.’

Jonny settles for another meek nod rather than try and say anything else. Paloma falls in step beside him as they walk towards the bus station.

‘It’s amazing how much it’s changed around here,’ she muses, gesturing towards the football ground a few blocks ahead.

‘How old were you?’ Jonny gazes at the stadium’s iconic silhouette. Boca Juniors, one of Argentina’s so-called Big Five and one of the best-known football clubs in the world. ‘When you first visited with your parents, I mean? I know you came loads.’

‘Two or three, I think? There’s a cool photo of me in a baby football shirt in front of the stadium. I only really remember the later trips. We never went anywhere else, so they all kind of blur into one.’

‘Wow.’ Jonny pictures Paloma as a baby – all inquisitive dark eyes and frown in the unmistakable navy-and-yellow Boca Juniors football kit. ‘And visiting during the war, too. Hard to believe the military were happy to allow tourists in and out. Your parents were committed, huh.’

‘To what?’ Paloma flicks a glance at him.

‘To Boca Juniors, obviously. You’d have to be, all the way from New Mexico.’

8‘It was a national shirt. Argentina all the way. But yes, I guess you’re right. We lived in DC then, I don’t remember anything about that either. They had US government jobs at the time. There won’t have been much that fazed them.’

‘I’m sure,’ Jonny replies, still wondering. ‘I suppose I just can’t imagine holidaying here while the repression was in full swing.’

‘It’s a big place. It takes two full days and nights of driving to get from here to Tierra Del Fuego. And that isn’t even the length of the whole country. It takes almost as long to get to the resorts in the Andes mountains. I keep telling you – you need to get out more.’

‘Tierra Del Fuego.’ Jonny tries and fails to pronounce the words properly. ‘The land of fire?’

‘It’s actually covered in ice that far south, but yes. It’s not much further to get to the Antarctic itself. But you don’t have to go all that way to do some exploring. Get out there – dress it up as work. You know the financial crisis is worse in the provinces. When I was a kid we spent most of our time over in the mountains by the lakes. They call it Little Switzerland.’

Jonny snorts. ‘Well the crisis is hardly biting down there. That place isn’t known as Little Switzerland just because of its alpine lakes and twee chocolate shops.’

Paloma throws him another look. ‘So you’ve been?’

‘To Switzerland?’

She swats him. ‘You know what I mean. I guess when I found out it was better known for all the Nazi war criminals who hid there for years I didn’t want to stay there either. But my parents couldn’t wait to get out of Buenos Aires. They wouldn’t even leave the airport after a while. We would just hang around until the next available connecting flight out west. They were always so busy at home, we hardly spent any time together outside of those holidays. But then all they wanted to do was go for long walks on their own. And still they wouldn’t let me stay behind in the city. It drove me nuts.’

9‘Is that why you won’t leave the place too now, like me?’

‘Nice try, buster. Stick to broadening your own horizons.’

‘Speaking of horizons.’ Jonny pauses by the stadium, distracted by the sight of the spectator stands stretching perilously high into the sky. ‘Are those the new bits, then? Those top tiers? They’re insanely tall. They can’t be legal in this day and age.’

‘You’ve obviously not been living here long enough if you think they would need to be legal to get built anyway.’

‘But you said everything had changed so much around here.’

She waves a dismissive hand. ‘I just meant that it used to be so much more rundown. The poorest, most deprived neighbourhood in the city. Sure, it’s still shady as hell, but at least it doesn’t look like it now.’

Jonny tries and fails not to eye her bulky camera case. Paloma rolls her eyes.

‘What? I haven’t said anything.’

‘You didn’t have to.’

‘I just wish you wouldn’t carry it so visibly, that’s all.’

‘Don’t be so paranoid.’

Jonny blanches. A fancy, expensive piece of equipment on display in times like these? In a location that, by her own admission, is still hiding its reputation as one of the most deprived parts of the city behind its fancy colours? Worse, in a country where only fifteen years ago the former military regime lumped journalists into the same category as the underground revolutionaries waging a guerrilla war? Too influential to be trusted. Too much power to mislead the public. Dissidents by a different name.

‘Paranoid?’ he repeats.

‘Yes. Five minutes ago you were disappointed I hadn’t taken yet another shot of dancing in the street. Now you’re wishing I’d left the camera behind.’

‘OK, OK, OK.’ Jonny holds up his hands. ‘I just don’t like 10flaunting it, that’s all. Especially not around here. Carry it in a different bag or something …’

‘Lugging around an enticingly bulging rucksack doesn’t sound like a better idea.’

‘It wouldn’t take much to make it look less like a very expensive camera.’

‘What about when I actually have to get it out? I can hardly hide the lens.’

Jonny sighs, fingering the notebook and pen stashed safe below the wallet in his trouser pocket. ‘Look, I realise that sometimes it isn’t as easy for you to do the job as it is for me. That I get to be a bumbling Englishman apologising for every question, whereas you have to stick a camera in people’s faces. But money is getting tighter and tighter around here. Weren’t we just talking about exactly that? The only stories I can get into the bloody paper are the ones about a full-blown financial crisis, which, by the way —’

‘—don’t necessarily lend themselves to good pictures,’ Paloma finishes. ‘I don’t need reminding that I’m the one with more to prove than you at the moment.’

They start to walk again. Jonny finds himself shivering even as they leave the shadow of the stadium behind them. He can’t help but ask. ‘Are you honestly sure you’ll be OK getting home by yourself?’

Now shadows of a different kind are passing across Paloma’s face.

‘I can look out for myself, Jonny. I’m used to taking risks, you know. Sometimes I have to, to get the job done properly.’

He scuffs a boot into a crack in the pavement. Instantly he’s reliving the moment they met, at his first cacerolazo – an exclusively South American form of popular protest involving the deafening bashing of saucepans. Thousands of Argentinians had taken the contents of their kitchens to the streets that day to demonstrate their frustration at the government’s kamikaze handling of its economy. A few pots and pans had slammed 11directly into Paloma’s face while she was busy proving herself on a story about the financial crisis which did, in fact, lend itself to good pictures. There was so much blood pouring down her face by the end of it that he could see it even from his stupid safe distance away. The fact that those pictures eventually trebled the impact of his reporting is one he still feels uncomfortable with. She’s the one with the scars as a result, not him.

‘Don’t remind me.’

Her tone softens. She runs an unconscious finger down the angry red mark on the side of her face. ‘It wasn’t your fault. How could it be? We’d never met before, I didn’t even know you were there at first.’

Jonny tries not to stare. ‘That’s not what I’m talking about right now. This particular film of yours isn’t full of pictures of kitchen utensils. Whoever has developed it now knows precisely what’s on it. And it isn’t exactly pretty, is it? All I’m saying is that maybe both of us should go and pick it up instead of you going in by yourself. Just in case there’s an issue. Then I can see you safely to your door afterwards.’

‘It’s in the opposite direction.’

‘That’s my problem, not yours.’

‘And what about all those calls you have to make? The pictures on that film are worth nothing without some more interviews, and you know that.’

Jonny sighs. A tin can clatters as it rolls into their path on a draught of purple petals. The interruption seems to be enough to make Paloma relent.

‘How about I call you as soon as I’m back home? You do your job, I do mine. And we can have your choripanes tomorrow when we put all the pieces together.’

She flashes a smile and Jonny’s resolve instantly crumples. He makes a show of checking his watch to save face.

‘Fine, then,’ he mutters, still uncomfortable. She won’t be 12travelling in the dark, at least. But this particular film of Paloma’s can’t fall into the wrong hands. The problem is they are a long way from working out exactly who is incriminated by its most horrifying content.

Almost at the bus station, Jonny only realises he’s lagging when a warm hand tugs at his. Usually they would take the same route from here – Paloma’s apartment unit in the Congreso neighbourhood is a few bus stops before Jonny’s. He finds himself reflecting on how soon his lease is up for at least the eightieth time. There are vacant apartments in her building. Can he make a reasonable case for moving in there, since they are almost always working on something together? A reporter needs a photographer and a photographer needs a reporter, otherwise their work is only ever two halves of a whole. And with that the dream takes hold – apartment doors a floor apart, fairy lights strung over their identical wrought-iron balconies, the smell of choripanes beckoning from his open window up to hers – Jonny sways on his feet just imagining it until he gets a very real whiff of the acrid fumes belching from the vehicles inside the terminal.

He pauses, reluctantly pulling his hand from hers. ‘You’ll call me?’

Paloma nods. ‘And I’ll be careful. Go on.’

Joining the back of the horde boarding his bus, Jonny has to resist the urge to look back. But by the time he’s squeezed inside, the vehicle’s small oblong windows are already thickly misted over – the tell-tale mark of at least a dozen too many passengers, as usual. Peering through the fog, Jonny is sure he can spot Paloma’s bus idling a few stands down. At least she won’t have long to wait, he thinks, squinting. Has she already boarded? But all he can make out is a blur as his vehicle pulls away, yawing on its way out of the terminus and into the traffic.

Jonny steadies himself with a hand on the metal bar overhead and tries to pick out some words from the streams of rapid 13Spanish humming all round him. Once Jonny prided himself on his grasp of languages, fluent in both Hebrew and English. But his mother tongue, as he used to call it, now only serves as a reminder of all he has lost. His first job in the Middle East wasn’t just Jonny’s first journalism gig, it was also a ticket into his past. By the time Jonny actually arrived in Jerusalem, having only just finished school in the UK, his Israeli mother had been dead for over ten years. But she’d been dead to her own parents for far longer than that – over something she never had the guts to tell Jonny she’d done.

He fidgets in the crowded aisle. Is that why, after more than a year scraping together a living in Buenos Aires, literally thousands of miles away from anything to do with his past, Jonny is still resolutely bad at speaking the local language? Because he associates speaking anything other than English with his mother’s betrayal? All he was ever told about their move to the UK was that it had to happen. That they had to start again after his mother brought unthinkable shame upon her family by marrying his father who, incidentally, also abandoned them both when Jonny was a baby. He sighs as he considers the real reason, so much more twisted than that. The fact is that Jonny was never meant to be alone – he wasn’t even in the fucking womb alone: he once had a twin sister who his mother willingly gave up to his father on the condition he left her and Jonny behind for good. And now Jonny is the one left alone, with no way of finding this fabled twin sister, with no memories of ever having a sibling in the first place – unlike his mother, who couldn’t live with the guilt in the end. She took her own life, he thinks, reliving a conversation that, almost fifteen years later, still makes no sense to him. As a bewildered and terrified nine-year-old boy, he hadn’t realised what the social workers meant when they came to break the news to him. They had to explain she had killed herself before he understood.

14He’s stuck so far in the past that he misses the clamour building behind him until a rough hand jerks at his collar.

Jonny looks down at another tug on his sleeve – it’s a woman, in traditional Bolivian dress, unmistakable with its vividly coloured shawls and bell-shaped petticoats crowned incongruously with a shiny-black bowler hat. The bus lurches the moment he feels for his wallet – yep, still stashed safe in his pocket – as if to physically reprimand him. Quite right too: was Jonny’s first instinct really to assume that as an indigenous woman she could only be out to rob him? The woman tips her face towards him, hat still somehow balanced perfectly on her head even though she’s craning her neck. But the next thing that happens is so unexpected that he has to crane his own, bending down to catch her every word.

‘Subversivos,’ she whispers urgently. ‘You understand? Subversivos.’

The bus lurches again before Jonny can reply, his mind spinning along with it.

‘Subversivos,’ she repeats. ‘They …’ she trails off, eyes darting, makes the sign of people walking with her tiny fingers.

‘Follow?’ Jonny finds himself whispering. He can’t believe what he’s hearing. The woman nods back, so vigorously that the hat should slip, but it doesn’t, polished dome blazing with conviction.

Jonny reels even as the bus steadies. Does this woman honestly mean to tell him he is being followed? Who is she? How on earth would she know? And what the fuck is the Spanish word for ‘follow’? He thinks of the notebook in his pocket, the scribbles that would surely make sense to no one but him unless paired with the pictures on the roll of film currently coming into focus in a deliberately random darkroom.

By the time he’s collected himself the woman is hunched away from him, an impossibly small mound in a sea of people, showing only the top of her bowler hat.

15‘I don’t understand,’ he whispers as if she can hear him, but the hat doesn’t flinch. ‘No … No entiendo. I’m being followed? How do you know that?’

And now she’s just gazing at him with an expression as nonplussed as he’d have expected from a native Bolivian woman being harangued by a sweaty Englishman on a packed public bus.

He raises his voice, he can’t help himself. ‘Do you understand me? What do you mean?’

But not even a flicker of recognition crosses her impassive face. An elbow now, digging into his ribs. Is it any wonder? Jonny knows he’s making a scene. Then another, followed by a shove. A swarthy man, as squat as he is burly, forcing himself between them. A stream of invective that Jonny doesn’t need to understand to know exactly what it means: Lower your voice. Leave her alone.

‘I’m sorry,’ he gabbles, straining to see over the man’s shoulder to find the hat has already been swallowed up by the rest of the crowd on the bus. The man glares at him, more unmistakable invective, puts in a shoulder for good measure. Jonny holds up his hands, finally musters up some comprehensible Spanish, manages to edge round the man towards the doors sighing open as the bus pulls into a stop. Up ahead, the bowler hat finally reappears, its patent shine bobbing in the gaggle dispersing across the pavement.

‘Wait!’ Jonny cries out, stumbling off the bus into a jolt of petrol. She’s moving quickly now, are there more hats in the crowd? He concentrates on following a flash of brightly coloured shawl. Ducking off the pavement and into the adjacent square, he realises the bus had made it as far as Plaza Miserere. Good, his unit is only a short walk away; but it’s almost impossible to locate anyone amidst the jumble of street-market stands.

Breathing hard, he pulls up short, scanning the plaza for the shiny-black bowler hat he knows will have long disappeared. While it isn’t exactly common to find native Bolivian women in some parts of the city, Plaza Miserere is one place they can blend 16in. It’s usually impossible not to spot their distinctive hats and skirts – sometimes even a live chicken flies out from under a tumble of petticoats. But here, jostling with the street vendors that come from all over the South American continent, even birds don’t register. Plaza Miserere is one place where the only people that can’t disappear are people like him.

Jonny drops on to a bench parked in the shade of a giant rubber tree. This woman was as identifiable as she was forgettable. Which means she took a risk, a big one. There is a certain amount she must have known – but how? And why? He rubs his temples as if he can physically push the different theories scudding through his head into a single, coherent whole. A sudden draught of candied peanuts wafts up his nose, so sweet he can almost feel the sugar rush coursing through his body.

Digging into his pocket for some change, he finally realises what is missing.

His wallet is still there.

But his notebook is gone.

Chapter Two

Even though it is pointless, Jonny retraces his steps: back out of the plaza on to one of the city’s main arterial avenues, pavements littered with discarded cigarettes, crushed tin cans and bottle-tops – everything except his damned reporter’s notebook with its distinctive buff cover, the one that gives him a pathetic thrill every time he notes the word ‘reporter’ on the front. He kicks at a crack underfoot, digging around in his empty pocket as if he can physically reconstitute its pages.

His notebook had to have been deliberately filched, otherwise why would his wallet still be in place? Is it possible it was a mistake, made by an incompetent petty thief? Jonny pulls into a doorway, turning the wallet between his fingers. In the cramped space and dim light of the bus, he supposes they could have felt the same. And it is more likely that someone rooted around for the first thing they could find and came up with something completely useless. If so his precious notebook is probably disintegrating somewhere in the drains halfway to the bay by now.

A sudden, sharp rattle from behind prompts him to stash the wallet again, but it’s only two elderly gentlemen squeezing past with folding chairs and a camping table, ready to set up on the pavement for a game of draughts. Something snags in Jonny’s mind as he watches them chunter back and forth. That mystery Bolivian woman knew to speak to him in English. Jonny’s been in Buenos Aires long enough to know that most people dressed so traditionally usually speak one of the many indigenous languages of the South American continent over the Spanish of 18their colonisers, and certainly over English. That woman clearly had a point to make. So was she the one who took the notebook? Was that her play all along? Distract him while she went into his pocket for something far more valuable to her than his stupid wallet?

Jonny dashes past the elderly gentlemen and sprints back into the plaza, trying to remember exactly what he wrote down. There were names and dates, different theories and possibilities. Feeling suddenly winded, he stumbles back to the bench under the rubber tree. But just as he sits, he remembers.

She said Jonny was being followed. And if she was right, he’s done nothing over the past few minutes other than meander around in stupid, misguided circles.

Suddenly grateful for his wallet over his notebook, Jonny hurries to a curio stand, bursting with vibrantly coloured knitted hats and scarves. Grabbing a random handful, he proffers a clutch of crumpled peso notes to the vendor, and despite the heat of the late-spring afternoon – spring in November, Jonny still can’t get used to it – he jams a knitted hat on his head and wraps himself in a scarf. Cornering the sprawling train station on the plaza’s northern tip, the smell of candied peanuts gives way to the acrid belch of fuel. Jonny speeds round the last few corners to the heavy wrought-iron gates of his apartment unit a few blocks away.

The familiar chorus of street patois greets him as Jonny fumbles for his keys – yep, still safely in his pocket with his wallet. He’d hand over the keys in a flash if he could just find his precious notebook. The usual cluster of men are crouched on the pavement outside searing something unidentifiable on a small, makeshift grill. When Jonny last asked, this group had numbered a Colombian, a Peruvian, two Bolivianos and a Paraguayan. At the time he’d been sure they were making it up as they went along just to mess with him. He’d even played the dumb gringo, given them a laugh at his own expense – these were men he’d rather have on 19his side than not, parked on the street outside his apartment block every day and night. But now he finds himself wondering whether they’re not just using this stretch of pavement as a kitchen, but are here for another reason. Fitting his key into the lock, the heavy iron security gate clangs opens into the small shared courtyard. Checking behind him, to make sure no one’s looking through the gate, Jonny is finally able to rip off his knits, taking the iron staircase two steps at a time, up to his small studio on the top floor and dropping his pile of fabric just inside the door.

The phone line rings out for a full minute after Jonny’s picked up the receiver and dialled Paloma’s number. She’s not there yet, of course; the shop where she left her film to be developed is in the opposite direction to where they both live. He peels off his sweat-soaked shirt, flinging it on to the bare floorboards in frustration. The open window doesn’t do him the courtesy of ushering in even a puff of fresh air. Squeaking open the tap, he draws a glass of water, trying to steady himself for long enough to consider what he knows.

It’s been nearly two weeks since Jonny started investigating something other than Argentina’s looming financial crisis. Nearly two weeks since the grisly discovery of a woman’s body washed up on a city beach – no, Jonny is already correcting himself, dropping into one of his two rickety dining chairs. That’s only what they were told. What Paloma was told. He kicks at a table leg, instantly regretting it as water slops all over the place. Jonny is the reporter in this relationship. By now he should be the one fluent enough to do some of the talking instead of letting his Mexican-American colleague translate for him all the time.

He takes a gulp of water, starts again. What he knows is that it’s been nearly two weeks since the body was found – or since Paloma and Jonny found out about it. Body parts, rather than an intact corpse. Headless, the police-issue crime-scene photograph had confirmed, with no fingerprints because there were no fingers 20left either, the only identifying mark a faded tattoo of a bird on the chest. Jonny twists round to consult the map pinned on the wall behind him, running a sweaty fingertip the short distance down the coast from Buenos Aires to the beach in question at the community of La Plata, known as the city’s southernmost suburb.

The horrifying crime-scene photograph reassembles in Jonny’s mind with inescapable clarity. These beaches are not virgin sands. Argentina’s Dirty War saw to that some fifteen years ago. He reaches over to his tiny bookcase to consult the threadbare historical textbook he seems to spend all his time re-reading. Argentina’s military dictatorship terrorised the country for almost a decade, propped up by the might of the United States, more terrified of the rise of Communism than the rest of the South American continent put together. Death squads stalked the streets with impunity. Thousands of alleged political dissidents were arrested, tortured and killed – many on the so-called Flights of Death.

Los Vuelos de Muerte, Jonny thinks, the sweat on his back turning cold. Whole planeloads of prisoners spirited away, drugged and hogtied, to be flung out into the open skies over the sea. Where better to hide the evidence of a killing machine as brutally efficient as Argentina’s former military dictatorship than the icy depths of the Atlantic Ocean? No one would ever have been able to prove what really happened were it not for the ocean tides inexorably moving some human remains back on to dry land. But the burden of proof is still the size of the Andes. Thousands of bodies simply disappeared.

Jonny considers this, flipping back and forth through the well-thumbed pages. The Dirty War ended fifteen years ago. He doesn’t need a textbook to tell him that bodies don’t survive intact in water for that long. And there are plenty of other reasons why a corpse might find its way into the water in a city like Buenos Aires. Drugs. Gangs. Money. Revenge. People getting angry. People getting even. People sending messages in the vilest of ways.

21Jonny’s finger stills on a random page. The echoes of the Dirty War in this case seem far too convincing not to be at least partly deliberate. The similarities to the most inflammatory period of Argentinian history are, in fact, glaringly obvious. And yet this latest discovery hasn’t hit even the local news headlines. Why? He flicks to a more recent chapter, reminds himself how influential the military remained even once the war had ended. Democracy was only restored after the economy collapsed. But the incoming president had to waive the prosecution of crimes committed by the former military regime to hold off another coup. The amnesty is still in place, leaving commanders accused of the most heinous of crimes free to mix in Argentinian society.

Jonny snaps the book shut. Is that the reason local journalists are keeping the news off the front pages? Human remains showing up on a popular city beach is a top story whichever way it is spun. But Jonny’s been scouring the papers for days now and come up blank. Evidence of an attempted disappearance fifteen years after the end of the Dirty War would mean elements of the former military junta are still operating underground, with state-sponsored impunity, sending gruesome messages of their own. That’s the real news story here. But Jonny has to prove it.

Dropping the book on the table, he paces back to the window. In order to get anywhere with this he needs to identify the victim. The police haven’t made any headway yet, or at least, aren’t willing to tell Paloma and Jonny if they have. In fact they were hustled out of the local police station after barely ten minutes of looking through the state’s official files on missing people. How exactly is he expecting to do it alone? Drugs. Gangs. Money. Revenge – these are the fearsome criminal enterprises he’ll have to discount from the equation, and that’s only if he’s right.

Jonny digs around for his notebook only to turn his empty pocket inside out with a howl. Despite the growing campaign for justice, the Dirty War is still a difficult matter to research openly. 22International outrage at the continued whitewash is one thing. But asking questions with the Argentinian military still at such close hand is quite another. And for those answering, it is clear there is still danger. The complex where most alleged dissidents were imprisoned and tortured remains operational as a military training facility in a fancy Buenos Aires suburb. The woman Paloma and Jonny quietly met with earlier even admitted to using a fake name, despite discussing her missing children for hours on end. The yellowing photos shaking in her gnarly brown hand flash into Jonny’s mind – her daughter Mercedes, only seventeen years old when she was arrested on a street corner on a charge of consorting with the wrong people. The same for Pablo, her son, six years older and labelled a dissident just for being an academic. And now he’s lost his record of their entire conversation.

Jonny eyes the movements on the street below the window, trying to remember every last detail scribbled into his missing notebook. Who could be interested in the scant information he has so far accumulated about this most recent body on the beach? And why? That’s not all that’s bothering him. Paloma and Jonny can’t be the only ones the local police tipped off about the corpse. The information practically landed in Paloma’s lap. And all so-called exclusive news leaks come with an agenda attached to them, especially when handed out to junior reporters like Jonny Murphy from the International Tribune.