7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Bastei Lübbe

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

At some stage, Wilson Lowery’s life took a wrong turn. When he finds himself in the hospital after an alcohol and drug-fueled binge, the doctor gives him an ultimatum to either turn his life around, or die.

Depressed and without a safety net, he signs up to become a Green Beret in the U.S. Army. Soon after he enters basic training, he realizes that he isn’t cut out for the army and tries to quit, but he isn’t allowed to leave. The especially demanding first weeks of training put him over the edge. Constant ridicule, lack of sleep, and excruciating group exercises at any hour of the day become his dark reality. Wilson’s outlook worsens when his basic marksmanship training begins. When he shoots at targets, he knows that in his heart he could never kill someone. Wilson refuses to train again, but is still kept on base without an end in sight. His punishment for trying to quit is so intense that he attempts suicide. However, even that doesn’t allow him to be immediately discharged from the army and the road is long and full of obstacles until he finally finds his freedom.

About the author

Wilson F. Lowery is a freelance writer and a first-time novelist specializing in creative nonfiction. Wilson's work has appeared on blogs and in independent online magazines. His creativity and passion for writing comes from his personal observations, successes, and failures that he experienced while growing up in Jacksonville, IL, through his formative years after graduating from college. Wilson obtained a B.A. in English from the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, where he currently resides.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 307

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

About the book

About the author

Title

Copyright

Chapter One — First Resistance

Chapter Two — Hell Week Begins

Chapter Three — The Phone Call

Chapter Four — Total Control

Chapter Five — Gas

Chapter Six — Giving It a Go

Chapter Seven — Kill Shot

Chapter Eight — Here Comes My Captain

Chapter Nine — Seclusion

Chapter Ten — Closer to Home

Chapter Eleven — Decisions

Chapter Twelve — Welcome Back, Private

Chapter Thirteen — The Warmth of Forgiveness

Chapter Fourteen — Father’s Forgiveness

About the book

At some stage, Wilson Lowery’s life took a wrong turn. When he finds himself in the hospital after an alcohol and drug-fueled binge, the doctor gives him an ultimatum to either turn his life around, or die.

Depressed and without a safety net, he signs up to become a Green Beret in the U.S. Army. Soon after he enters basic training, he realizes that he isn’t cut out for the army and tries to quit, but he isn’t allowed to leave. The especially demanding first weeks of training put him over the edge. Constant ridicule, lack of sleep, and excruciating group exercises at any hour of the day become his dark reality. Wilson’s outlook worsens when his basic marksmanship training begins. When he shoots at targets, he knows that in his heart he could never kill someone. Wilson refuses to train again, but is still kept on base without an end in sight. His punishment for trying to quit is so intense that he attempts suicide. However, even that doesn’t allow him to be immediately discharged from the army and the road is long and full of obstacles until he finally finds his freedom.

About the author

Wilson F. Lowery is a freelance writer and a first-time novelist specializing in creative nonfiction. Wilson’s work has appeared on blogs and in independent online magazines. His creativity and passion for writing comes from his personal observations, successes, and failures that he experienced while growing up in Jacksonville, IL, through his formative years after graduating from college. Wilson obtained a B.A. in English from the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, where he currently resides.

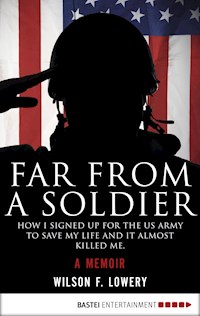

FAR FROM A SOLDIER

How I Signed Up for the USArmy to Save My Life and ItAlmost Killed Me

A Memoir

byWilson F. Lowery

BASTEI ENTERTAINMENT

Digital original edition

Bastei Entertainment is an imprint of Bastei Lübbe AG

Copyright © 2016 by Bastei Lübbe AG, Schanzenstraße 6-20, 51063 Cologne, Germany

Written by Wilson F. Lowery

Edited by Gail Werner

Cover illustration and design: Christin Wilhelm, www.grafic4u.de; © shutterstock/Marko Marcello

E-book production: SatzKonzept, Düsseldorf

ISBN 978-3-7325-1554-7

www.bastei-entertainment.com

Chapter OneFirst Resistance

At some point during the day, without fail, I feel completely ashamed. It doesn’t matter what I’m doing, where I’m situated, or what time it is. Something always seems to pass by me. A shirt. A person in uniform. A gun-supporting bumper sticker. A magnet made in China, supporting our American troops.

During these moments, I wish I were dead. Or at least living alone in a town where no one knows my past. Instead I’m stuck here in this strange skin of mine, living with my decisions and my regret, always carrying an immense sense of shame.

At times I hate myself because of two decisions I made when I was twenty-two, two years after two planes slammed into the Twin Towers.

I was living in Chicago nine months after the 9-11 attacks. Having pumped my body full of alcohol and drugs, I found myself in an intensive care unit with a case of acute pancreatitis. Lying there in a hospital bed, I was delivered an ultimatum by a doctor: turn my life around or die.

When they released me, I didn’t know what to do. Depressed and without a safety net, I considered staying in Chicago, returning to my old ways. Instead, I called my parents and begged to come home. A few months later, I was sitting next to Dan, both of us wearing U.S. Army sweats, carefully watching a drill sergeant pace in front of a stage.

***

“I think it won’t be so bad once we get down there.”

“Fuck that, man. I’m not going and I’m not filling out this paperwork,” Dan whispered to me.

“I think that’s a big mistake. You have to go to the training before you can get out of here.”

“I don’t give a shit. I’m not going.”

As the drill sergeant moved from one side of the auditorium to other, he shouted out directions about what papers to sign and what stickers to place on the empty containers lying on the desks in front of us. Dan and I were front and center in the first row, my left leg shaking from nerves.

“Look, man,” I said, “I think you should just fill this stuff out. You’ll never get out of here if you don’t do the paperwork. If they’re gonna process you out, you have to be processed in first.”

I made a poor attempt to act as if I knew what I was talking about, even though I didn’t know a damn thing. I was only repeating some of the bullshit I’d heard from other kids who’d previously tried escaping from basic training.

“I’m not going to fill out a goddamn thing. Fuck this army and fuck this paperwork. They can’t make me do a fucking thing.”

“Dan, I’m telling you, it’ll be in your best interest if …”

Right about then, I looked up to see the instructor glaring at Dan.

“That’s a nice pink vest you have on there, private.”

Dan looked down at the pink vest he was ordered to wear as a result of expressing resistance to training two days earlier. He had been sent to see a mental health professional and was deemed “high risk.” They made all the guys who fell into that category wear those vests. Easier for the drill sergeants to keep their eyes on them, I guess.

“What the fuck is so funny? Who the fuck gave you that pretty little vest?”

Dan didn’t say a word. The drill sergeant studied him with disdain.

“Private! Why haven’t you filled out any paperwork?”

In a low, shivering voice, Dan replied, “I don’t have to.”

The drill instructor drew in a huge breath. “YOU DON’T WHAT?!?!”

Everyone in the room dropped their pens, their eyes and ears focused on the front row.

“I said I’m not going to fill it out. I don’t want to be here,” Dan replied, his voice suddenly timid.

“Private, if you don’t want to be here, why the fuck did you sign up to be a soldier in the United States Army?”

“I don’t know.”

“Bullshit, private! You want to escape, don’t you, you little fuck? That’s why you’re wearing that pretty pink fucking vest, huh?”

Dan didn’t say anything, but I could see the tears forming in his eyes. His hands were shaking. He was mad and terrified at the same time, on the verge of losing control. Being so close to the situation, I wanted to jump out of my chair but couldn’t move, nor could I act like I was interested in what was happening next to me. I knew if I paid any attention to the situation, the drill sergeant would see my sympathy for Dan and make an example out of me too.

“Private, you have to fill out that paperwork before you can even begin to be processed out, so you better get to work on them right fucking now!”

“I’m not going to fill anything out,” Dan replied loudly. “I don’t have to.”

“Fine private, be a stupid fucking jackass! Sit there you worthless piece of shit! That’s right—you don’t have to do a fucking thing! Just see where that gets you, goddamnit!”

Silence filled the room. The drill instructor had our attention but still commanded, “Listen up!”

We all stopped writing.

“This piece of shit right here in front of me is refusing to fill out his paperwork!” He bent closer to Dan and even though he was staring at him, addressed every one of us. “This little piece of shit thinks he can just walk the fuck out of here. But it sure as shit isn’t that easy! He’ll be down here for the rest of his life if I have anything to say about it!”

He stood back up.

“Now, if any of you pansy-ass privates want to follow in his footsteps, be my fucking guest!”

No one made a sound.

“That’s what I thought! You all know you signed up to defend your country, not to be a quitter like this piece of shit!”

He bent back down in front of Dan. “Isn’t that right?”

From my peripheral vision, I could see Dan shaking uncontrollably, tears pouring down his face. He lifted his hand to wipe them away, on the verge of hyperventilating.

Again the drill sergeant went off, lambasting him in front of all of us before telling him to leave. After the drill sergeant said his final words to Dan, he took a deep breath and held his head high as he stood and walked past us all.

After that, I never talked to Dan again. He was removed from our barracks, his bunk left empty. I often turned my head in its direction, hoping to see his face, but all that remained was a set of tucked-in sheets, too taut to welcome any history of him.

Sometimes I would see him moping around the barracks, hanging his head, possibly contemplating his decision to quit, but I never had a chance to say hi. He was kept away from the rest of us, isolated with the other recruits wearing those pink vests. Some said Dan had been relegated to the barracks set up for those with psychological problems, but I knew Dan wasn’t crazy.

The group he walked with was filled with kids who all had their paperwork in process to go home. Some had injured themselves on purpose, while others had been removed from training due to their lack of compliance. Then there were those who weren’t mentally fit for the army. One guy supposedly ran straight at a wall, his head leading the way. (The wall won.) How these kids were even recruited, I’ll never understand. Regardless, they were there—just like me. Miserable, lethargic, basically catatonic, they might have been ashamed or even ordered to behave that way. Still, I could see the strange sense of satisfaction they wore on their faces. I knew they were thinking about going home.

Chapter TwoHell Week Begins

Two days after Dan was removed from our group, I received word from a drill sergeant to have my platoon ready at 0300 hours in the morning. We were headed “down range” into our first day of true training and into the beginning of “hell week.” He gave me a list of things we had to do:

Clean the barracks top to bottom

Remove all bedding and place in pile outside barracks

Take all mattresses to room 302

All belongings packed into army-issued duffle bags

Battle Dress Uniforms on

Platoon seated on duffel bags by 0500

I went straight to my barracks and asked for attention. Before I could even say anything, someone yelled, “This is it! We’re fuckin’ goin’ down range boys!!!” Everyone in the room started yelling like they’d won some huge prize. No one acknowledged how stupid we were to be excited about entering hell week. We just wanted out of the boredom associated with the reception hall we had been stationed in for more than a week.

“Alright! Alright! Alright!” I shouted above the throng’s noise. “Before you get too fucking happy, you’ve all got a ton of shit to do!”

“Go fuck yourself,” one of them yelled with a laugh. Everyone else joined in.

“I’m fucking serious. If we don’t do this shit, we’re not going down range!”

“Oh, bullshit!”

“I’m dead fucking serious, so shut the fuck up!”

They paid closer attention as I read through the list. I was expecting their smiles to droop as I read off each task.

But instead of defiance, they wore looks of eagerness. It pissed me off a little, so I said with sarcasm: “Well, isn’t this fucking nice? Before I couldn’t get your lazy asses to clean a toilet or do a fire watch, but now look at you. You’d give me a blow job if I told you to!”

“Fuck you, Lowery!” another private yelled, his words met with more laughter, louder this time.

“Fuck you too!” I yelled back. “Now get to fucking work!”

By 0500, the outdoor corridor leading up to the reception station was a cacophony of profanity and speculation. There were hundreds of green duffel bags stacked together with a human companion by their side. The bags stretched from the entrance of the corridor back to the first set of barracks, nearly 150 yards in length. It kind of looked like a cemetery, except the headstones were bodies sitting on top of the bags.

The weather worsened, the temperature dropping ten degrees. We could see the tops of the dense evergreens swaying as the wind picked up and the rain started blowing. Fortunately the thick concrete ceiling of the corridor provided us cover, but it wasn’t enough. Soon we were all shivering, waiting for the morning sun to come up.

Since we’d been told to wait on our duffel bags at dawn, we thought for sure we’d leave before breakfast, but that wasn’t the case. We sat on our bags, watching new loads of recruits file past us in their sweats as they made their way towards the smell of bacon, hash browns, and syrup inside. Even though we were a little jealous of them, we still felt naively better than them. We were about to go into training while they had to sit and wait in a holding area before they’d get their chance. What they had ahead of them—getting their uniforms, their hair cut off—it was nothing prepared for what would come when the march into hell really began.

Eventually, we headed to the dining hall for breakfast. We lined up as usual, but no one cared to eat. There was so much excitement and apprehension that quite a few privates were forced to do push-ups for talking too loud about going down range. After breakfast, we marched back to our duffel bags, parking our asses on them for four more hours. When we stood to stretch, we were told to sit back down. When a drill sergeant or officer walked by, we had to stand. Over and over again this took place: stand, sit, get yelled at, do push-ups, stand, sit, get yelled at, do jumping jacks, etc. Morale started to sink to an all-time low.

We tucked our hands into our camouflage pants and wiggled our toes in our boots as the temperature dropped to around forty degrees. As I wiggled my toes I began noticing my boots were probably too big for me. I started to panic. Fortunately, a young, confident, yet somewhat nerdy guy named Roger who I’d met on the second day at the reception area was sitting next to me. Like me, he had the 18X military occupation specialty, or MOS as they called it, so we were both designated as potential Special Forces candidates. This meant we would need to help each other through training. He was sitting next to me, trying to close his eyes, so I startled him a bit.

“What?” he asked.

“I think my boots are too big.”

“Are you serious?” He stared at me through the enormous lenses of his military-issued glasses.

“Yes, I’m serious. Here, feel.” I stuck my left foot over towards him. “I’m surprised those glasses don’t come with x-ray vision.”

“Fuck you, man,” he said, reaching towards my foot. “Holy shit!” His eyes widen. “Those are enormous.”

“I know. What the fuck should I do?”

“How the fuck didn’t you notice they were too big?”

“Shit, man. When I tried them on, I hadn’t slept in a day. I probably wouldn’t have realized if they’d given me a pair of roller skates.”

“Didn’t you try them on again?”

“Fuck no. Why would I do that when I had tennis shoes?”

“To break them in.”

“Well, I didn’t, so what do I do now?”

“You better do something,” Roger said. “If you don’t, you’ll be seeing a doctor.”

I trusted his opinion. Roger had been preparing for Special Forces training well before me. He’d done his research and had even practiced marching with a weighted backpack. He may have looked like a skinny chemist, but he knew his shit: what to do without toilet paper; how to get creases out of uniforms without an iron; how to clean a weapon and take care of your damn feet, which I knew absolutely nothing about.

I told him I was going to get someone to look at them. I begged him to come find me if we got called to attention; he promised he would. I knew I could trust him and ran off to the reception battalion, down into the basement where the storeroom was located.

Luckily the civilian employees weren’t too busy to help. They laughed condescendingly when I showed them my boots, then asked why the fuck I hadn’t said anything. I didn’t tell them I was too tired to have noticed. Instead I shrugged my shoulders. Said I thought I wasn’t allowed an opinion at the time.

Without having to explain myself further, I watched the employee reluctantly walk off to retrieve another pair of boots. He returned shortly with a pair in my size. I put them on.

“You sure they fit this time, private?”

I smiled, nodding before running back up the stairs.

Roger was shaking his head as I rejoined our formation. As I started to explain how it went, three huge army trucks called deuce-and-a-halves pulled into the parking lot.

“Holy shit, man!” Roger exclaimed. “This is it!”

All I could do was nervously swallow and try not to shit myself. My mouth filled with saliva. I didn’t know what to think or do. I wanted to run.

We were ordered to our feet and roll call sounded off. Each of us shouted out our names with great pride, but you could still hear the hint of fear in our voices.

We were told to pick up our duffel bags and place them on our backs. They weighed about eighty pounds each. The first two rows of privates to my right were issued to move forward. The next two rows—the rows containing Roger and me—were to follow. After that, the remaining rows brought up the rear.

As we waited to march forward, we watched each private toss their duffel bags up into the arms of the camouflaged men standing at the backs of the trucks. We marched like ants around a picnic, the lines of new recruits curving past the reception battalion, around the massive trucks, and out towards the flagpole in the front yard. The flag was barely moving in the slow drizzle and slight wind.

None of the drill sergeants were yelling at us, because they didn’t have to. We knew what to do as we followed one another in apprehensive silence. Once we settled around the flag, we recited an oath similar to the oath we had recited just before we hopped a plane to head to basic training. This oath was vitally important, but I’m not sure any of us could tell what we were saying. We were too worried about our first day down range, having all heard stories about hell week. Sure we each had some vision of what it was going to be like, but we wouldn’t know for certain until we arrived there.

Immediately after the oath, each side of the square, which contained four rows of recruits, was ordered to march out behind a drill instructor and a flag bearer. Mine was the second side of the square to go. I heard the cadence being called, “Left …left …left, right, left,” ahead of our group.

“All right, men,” the drill sergeant shouted, staring us down. “Right …face!” We all turned awkwardly to the right. “Forward …march!”

“Left …left …left, right, left,” the drill sergeant kept repeating. We clumsily followed, trying to keep rhythm. The drill sergeant marched perfectly, yet his eyes remained on us, making sure we were keeping the cadence. About thirty seconds would go by before he’d yell, “Heads up, men!” All of our heads would rise, too many of us watching our feet. A few more seconds would pass before he would yell, “Shoulders back!”

I nervously checked the area as we marched, not wanting to tip off the drill sergeant I was curious about our surroundings. The road beneath my feet was formed of sand crushed into the asphalt, washed off the loamy southern soil. There might have been a dearth of happiness in that camp, but there sure wasn’t a shortage of sand. It seemed to be everywhere, as if old sand bags had been torn open and dropped from Apache helicopters. It seeped through the grass, clung to curbs, embraced the bases of brick buildings and buffeted the trees.

The trees were pervasive, primarily evergreens. They blocked the horizon, imprisoning us as we marched on. It was an eerie, depressing, and ominous march, each step bringing me closer to something I wasn’t ready to face. At the same time, I felt free, somewhat entwined with nature, yet trapped, lost and highly confused. I thought about bolting off to the left, into the thick wood of pines in search of a free city, one with taxis that could take me away from this mess.

There was nowhere to run though, especially without the sun to guide me. The rainclouds overhead made it impossible to tell which direction we were going. I was trapped in the woods of the army base, marching without a clue of where I was headed.

My feet were starting to ache after the first mile. I now realized why Roger had worked on his boots so much back in the reception battalion. When I first met him, he’d been methodically rubbing the leather, working them in like a baseball glove. He looked small and feeble, somewhat out of place, but as he messed with his boots, he asked how I was doing and if he could help me out at all with platoon duties.

Even though I could barely see his eyes through the thick lens of his glasses, I could tell he was a trustworthy guy. He had all kinds of tips about how to break our boots in, but I told him I’d let it happen naturally. He laughed, and now I knew why.

The leather wasn’t forgiving and I could feel blisters forming on my toes and heels. The burning got worse as we marched on, heightening my fears. All I could think about with each step was how it would hurt worse than the previous one. I tried walking a bit awkwardly, but that wouldn’t fly for long, because the drill sergeants marching alongside us were making sure we kept in line, acting as one unit.

We continued to march, making our way past some type of small medical building, then what looked to be a store. No one was outside. Everything seemed deserted.

We continued down to a four-way stop and then up a steep incline. I spied a large rectangular brick structure slowly presenting itself through a sparsely-populated clump of pines up ahead and to the right. There was an immense flag waving in the cold breeze, swaying back and forth above two antiquated tanks, firmly implanted in concrete platforms outside the company’s barracks. I wasn’t certain where we were, but I knew we were close to wherever we were going because the drill sergeant quit calling out his cadence. Instead, he dropped back to speak with another instructor and we kept marching to the top of the hill. One drill sergeant suddenly ran to the front, commanding us to halt.

Our company had been divided into four marching sections, each led by a drill sergeant. All of them came together, standing in a closed circle thirty feet from us. One of them had a walkie-talkie and they all seemed to be listening to it closely. Within seconds the drill sergeants broke from their circle and went back to each block of soldiers. We were ordered to march again, off to our right.

We marched past the tanks and headed along the right side of the barracks for Charlie (C) Company. The massive brick structure had an administrative center and, from what I could tell, two separate wings on each side. The building stood four stories high, stretching two hundred yards across and nearly the same to the rear, which wasn’t altogether visible at that point. As we passed, I noticed it had no windows, just bricks mortared together, trapped and immovable.

Off to the right was some sort of training course, complete with rope ladders, wooden towers, sand pits, and obstacles resembling adult jungle gyms. Beyond the course stood a forest of impenetrable evergreens. No life, other than ours, could be seen. The rain fell harder with each step we took, soaking through our camouflaged uniforms.

I saw the first group of new recruits round the corner and then heard yelling like I’d never heard before.

“Move it, you fucking pussies! Move, goddamnit!”

“Fuck you, motherfuckers!”

“Your ass is mine now, bitch!”

“What the fuck do you think you’re fucking looking at, you fucking piece of shit?!”

Oh no, I thought to myself. What the fuck did I do? Each step I took meant a step closer to the yelling behind the wall. I wanted to run, but I knew I would be caught and life would be hell. Besides, where was I going to go? To hide in the trees? That wouldn’t work. The army’s infrared goggles and heat-seeking missiles would find me. I was fucked.

“What the fuck, private? If you look at me again, you’re fucking dead!”

“Get your mother fucking asses over here! Do it now, motherfuckers!”

We rounded the corner and saw nearly sixteen drill sergeants standing with their arms akimbo, shouting obscenities as water cascaded off the brim of their hats.

The first group of privates was already lying on the ground, rolling around in the mud, trying to do push-ups, sit-ups, or whatever else was being ordered of them. Beyond them were the large trucks carrying our gear. Camouflaged men were tossing the bags into huge piles, rain soaking everything. It was impossible to focus on anything but the fear I was feeling.

“What the fuck, private?” a drill sergeant asked me directly. “You just going to fucking stand there or are you going to move like the rest of them?!”

“I’ll move, sir,” I yelled best I could. I attempted to take off in a sprint, needing to line up in the mud for my push-ups. Before I could take two steps, he grabbed hold of my shirt, stopping me.

“You didn’t move fast enough, you mother fucking slow-ass pussy! Your ass is mine now! Get the fuck down on the ground and don’t stop pushing until I say stop!”

I dropped to the ground and started doing push-ups as he continued to cuss at me. Rain poured over the back of my head, the water running into my eyes and up my nose.

“I don’t fucking here you counting, motherfucker!” he yelled.

“Ten. Eleven. Twelve …” I let my chest drop almost to the ground and then he ordered me to stop.

“No, no, no, no, no, you lying piece of shit! You can’t just start counting at eleven. You have to count over starting at one. Do you understand me, private?”

“Sir, yes, sir!”

“Now start fucking counting!”

I didn’t even think about the strain or the cold. All I could do was worry if this asshole was going to hit me, or possibly place his foot on my back. I wasn’t sure what all these drill sergeants could do to me and I sure as hell didn’t want to find out, so I started my push-ups all over again. As I did, he kept yelling at me, calling me a dick, bitch, fucker, shithead, pussy, and faggot.

I caught a break when the entire company was ordered into ten rows. We all labored to gain perspective on our surroundings. Our rows drunkenly formed as we bounced off one another, stunned from the physical toll taken, mixed with the stead rain.

We were told to keep our arms out to our sides and to stay that length apart from one another. The rows stretched at least two hundred feet in length. With each blink, rain fell from our eyelashes.

“I’m sure you privates think this is going to be easy, don’t you?” asked one drill sergeant.

“Sir, no, sir!” we shouted back.

“I can’t fucking hear you, privates!”

“Sir, no, sir!”

“I bet you all think the army isn’t as tough as the marines, don’t you?”

“Sir, no, sir!”

“What did you say, you pieces of shit?”

“Sir, no, sir!” we yelled louder.

“Let me tell you something, privates,” he said as he walked between rows, his figure barely visible in the falling rain. “You have been misled if you thought this was going to be easy! You have been misled if you think the army isn’t as tough as the marines! Shit—” he chuckled—“we’re definitely not the air force or the navy!” The other sergeants laughed. “The marines are some tough motherfuckers, but they’re not as tough, not as strong, and not as large as the army! Do you hear me, privates?”

“Sir, yes, sir!”

“What, motherfuckers?”

“Sir, yes, sir!”

“I can’t fucking hear you! Now sound the fuck off!”

“Sir, yes, sir!” we shouted this time, our cries absorbed by the trees surrounding the battalion.

“You know what time it is, Sanchez?” the drill sergeant asked the meanest looking sergeant on the lawn. You could sense the man was evil.

“I’m thinking it’s time to smoke these little bitches,” Sanchez replied with a hungry grin.

“That’s right, motherfuckers! It’s time to get smoked!”

If anyone had asked me three months prior if I’d wanted to get smoked, I would have emphatically responded “Hell yeah!” Until this moment, those words had meant getting high. The army’s version, however, wasn’t what I was used to.

If people ever question the ingenuity of the army, I’ll tell them about how the army has engineered what’s probably the most brilliant physical fitness facility ever created. They don’t use weights, and yet they still manage to make you feel as though you’ve torn every muscle in your body within a matter of minutes. We were ordered to clap our hands over our heads. Easy enough, right? All we had to do was extend our arms out to our sides, palms down, then lift them above our heads to meet in a clap. I think we all felt a little ridiculous, doing something so simple. What we didn’t know was how long we’d have to do it. Instead of doing this for a minute, we must have exceeded ten minutes of these to start. We did hundreds of overhead arm claps, possibly thousands. I’ll never be sure. All I know is I could hardly lift my arms after we were done.

This “getting smoked” business went on and on and on. We did hundreds of crunches and leg lifts. Some guys would tire out, but if they dropped their legs to the ground, or fell back gasping for air, within seconds drill sergeants would make their lives a living hell by yelling at them without indiscretion. Every word in the book of cuss words and slang would be shouted. I don’t think there was a single person on the receiving end of it who wasn’t crying or, at the very least, on the verge of tears. It appeared as if all of us had come from some type of damaged past or broken home. All of the yelling took us back in time to a specific episode we were desperately trying to forget. It didn’t matter how strong any of us were by that day; we all fell at some point.

The worst exercise of all was called a pike push-up. To do one, you get down in regular push-up form, then keep your feet in place and walk your hands back toward you a few feet. Once your ass is up in the air, you try to dip your face to the ground, between your hands. Once there, you pause before pushing your body back to the starting position. When we did these, I know I cried a little because of the pain. I thought I actually tore muscles and tendons in my shoulders. When I fell, I was picked back up by drill sergeants and forced to do them again. I usually landed flat on my face; I’m surprised I didn’t break my nose.

Everyone struggled at some point. Whenever anyone fell, within seconds, they were attacked with the same vulgarities leveled at me, spit flying from the mouths of the drill sergeants as they screamed and yelled. No one could escape. No one was able to mask the pain. At times the drill sergeants would allow us to stand, which is when we’d notice how dejected and miserable we all looked. Rain and mud saturated our battle dress uniforms(BDUs). Luckily the rain masked the tears we all knew were there.

After what seemed like two hours of this torture, we were ordered to run to the piles of bags, grabbing one a piece—it didn’t matter whose—before running with it to the courtyard at the barracks. We all moved as fast as we could, almost trampling each other to reach them. The bags, which had once felt manageable to bear, now felt like they had the corpse of John Candy inside them. Most of the guys ended up dragging theirs back through the rain-soaked lawn.

The opening of the barracks was wide enough for a large vehicle to drive into. The ground floor had two areas to stand under and keep protected from the elements. We were split in half and ordered to line up in equal number on either side of the area meant for vehicles. The captain’s office, the main staircase, a recreation room, and a storeroom were opposite the opening to the lawn. There was an administrative desk outside of the captain’s office, just to the left of the main stairs. Two or three sergeants were leaning against it, eyeing all of us, hedging their bets as to who would be the first to try and quit.

Some of us stood at attention while others hunched over in pain. One drill sergeant stepped forward and shouted our next order: We had one minute to find our own bag. That was the only instruction given us before a whistle was blown. Most of us began scurrying around, while some simply stood by the bag they’d carried in, calling out the name listed on its side. It was extremely chaotic and loud. People were shouting names, others were running into one another, and some were even arguing over a bag or two. The whistle blew about thirty seconds later. Bags were everywhere and the once neat rows looked like damaged cars in an interstate pileup.

“You motherfuckers can’t do anything right!” a large black drill sergeant yelled. “Get the fuck back out in the yard!”

We all ran outside, lining up like we had when we arrived. We were ordered to do twenty minutes’ worth of more exercises. Before this moment, most of us could do at least twenty push-ups in a row. Now we could barely get in five. If one of us dropped, the drill sergeants were on top of us; yelling, screaming, and cussing. After our smoking was through, we ran back into the barracks. Again we were given one minute to find our bags and to stand beside them. We failed again, but nearly half of us had our own bags this time.

Again we were ordered back out into the yard. Again we endured a great deal of exercises and obscenities. After our quick workout, we once again ran back into the barracks, trying to accomplish the task of finding our own bags. But of course, once again we failed. The exercise was designed to make us work together and deal with failure. It was our first take at working as a team, being able to deal with our frustrations while under stress. The thing is, at the time, we couldn’t see the point of it since we were so tired. This “exercise” took place two more times until finally we succeeded. What was our reward? Another workout.