Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

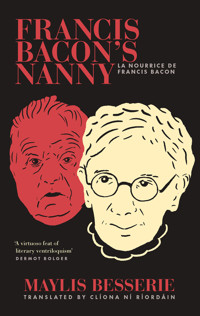

At the very centre of the life of one of the twentieth-century's greatest artists was the most unexpected of life-long influences. The aptly named Jessie Lightfoot shielded the young Francis Bacon from the brutish violence of his bullying father, as well as from his worst self-immolating excesses later in life. The tenderness, wit and warmth of this inimitable Nanny stands in illuminating relief to the sulphurous palette that defined Bacon's work. Beyond the humour and heart of this extraordinary woman – who finds herself confronted with the shade and guile of the artworld – Maylis Besserie also gives us a glimpse of Ireland in the first half of the twentieth century, both a powder keg and a place apart from the rest of the world, whose landscapes, imagery and animals haunted the famous painter's canvases. In the final of Maylis Besserie's Irish-French trilogy, her preoccupation with the art and lives of artists who crossed borders between France and Ireland has a fitting climax as Bacon confronts the boundaries between the real and the imagined. 'In a virtuoso feat of literary ventriloquism, Maylis Besserie follows the advice of the Greek poet Cavafy to approach the world from unique and strange angles. Through the eyes of Bacon's nanny and close companion, she gives us brilliant insights into the conflicting personal, sexual, and artistic impulses that shaped a remarkable artist, rendered in the steadfast voice of someone who understood and loved the complex man behind the art. It marks a wonderful conclusion to a remarkable Irish trilogy.' Dermot Bolger

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 304

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FRANCIS BACON’S NANNY

By the same author

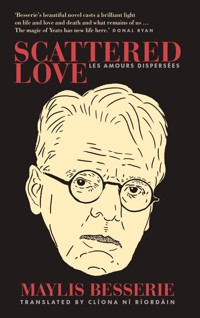

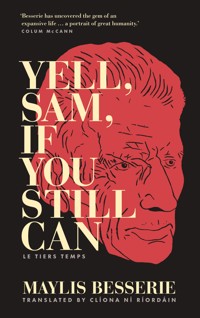

Yell, Sam, If You Still Can Scattered Love

FRANCIS BACON’S NANNY

L A NOURRICE DE FRANCIS BACON

MAYLIS BESSERIE

TRANSLATED BY CLÍONA NÍ RÍORDÁIN

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

First published in English in 2024 by

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

62–63 Sitric Road, Arbour Hill

Dublin 7, Ireland

www.lilliputpress.ie

First edition, La Nourrice de Francis Bacon © Éditions Gallimard, Paris 2023

Copyright © 2024 Maylis Besserie

Translation © 2024 Clíona Ní Ríordáin

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher.

Quotation from T.S. Eliot’s poem ‘Fragment of an Agon’ (1927) reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber.

A CIP record for this title is available from The British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84351 888 4

eISBN 978 1 84351 927 0

The Lilliput Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon.

Set in 10.25pt on 18.25pt LeMonde Livre by Compuscript. Printed and bound in Sweden by ScandBook.

What remains in the end? A pile of bones and a few teeth.

FRANCIS BACON

PROLOGUE

Portrait of Jessie Lightfoot, Nanny

When it soliloquizes, Jessie Lightfoot’s mouth scarcely opens – a tight trap on a mouse’s snout. Not really a mouth, more of a line, a slit on a money box, a wave of flesh drawn inwards. Difficult to determine what will go in and what may come out. Difficult to distinguish between an ordinary mouth and a vampire’s ghoulish maw or an oracle’s orifice. The only thing needed is an opening, with jaws ajar for it to become something else entirely, for a hilly landscape in shades of pink to appear in a sky of serrated ivory. It all depends on the chosen moment. A mere yawn in the middle of a feast and you are plunged into the abyss, into the dark den of massacres, into the kingdom of the carrion-eaters where the juices from bites are sprayed, where bones and cartilage creak. In the case of extreme pain or imminent danger, the view of the mouth is not the same of course: it opens as widely as possible with lips ready to split, and sharpened teeth bared just in case. As for the black depths of the orifice, it shakes to the vibrations of the shriek that escapes from it like ether into the skies, thundering alongside them. The mouth is so changeable, so chatty; it’s the maw of all humanity, all for one contained within it. A mystery.

What can Jessie Lightfoot say in the present day? Now that she is frozen on canvas, immortalized. Her teeth one day may have the better over the meat that envelops them. The mouth may be eaten by itself like the rind exposed, forever opened – maxillary on show, incisors on offer. Unless the reverse happens and the skin becomes leathery when it comes into contact with the hard teeth, a leather mouth on a hippopotamus, a rustic cow’s rump. Another possibility is that the damp mandible might gather speed and end up spitting out miles of chops as thick as a tongue. No. Not this mouth. Not Jessie Lightfoot’s mouth. The painter’s nanny, his mother, is forever suspended over the swing of his childhood. Bathed in an ocean of green. A naked goddess, with an open mouth, every night it tells anyone willing to listen, what teems between the weft of this canvas, what the granular painting has revealed and covered up. The winds of memory blow over the portrait of the nanny whom the painter has made eternal. They still blow over the injured child lying on the straw to warm himself up. The child whose father left him bloodied, who braved hatred before meeting Nanny. Who spent his whole life dodging the whip.

First Tragedy

THE FATHER

NANNY

I seem to be there still, feeling the rain lashing down on my cape, water seeping into my bones as I walk through the door of Cannycourt House, introducing myself like a drowned rat to Mr and Mrs Bacon – ‘Jessie Lightfoot, I’ve come for the job as a nanny …’ No sooner had I finished greeting them than my boots, which were full of holes, began to spew out all the Irish mud I had picked up on the paths, soiling the carpet in the great hall at Cannycourt House. I can tell you that I felt ‘as guilty as that cat who just ate the canary’, as my mother used to say! Ah, I can assure you that I didn’t dawdle, I took my leave and scuttled off towards the children’s quarters, and the servants who showed me the way followed me like shadows, mopping away my errors. Talk about making an entrance, having to slink away, slithering like a snail all the way down until I reached the corridor when I could finally take off my bloody boots. And then who did I see coming towards me? Two little fellows, as tiny and handsome as could be: one standing up, the other on the floor, Harley trotting along with his head down like a damned soul while my baby Francis crawled at his feet, polishing the floor with his saliva, wiping it with his belly. A beautiful baby, he is, I can’t believe it – lamb’s eyes, face as round as an apple. And such cheeks. But mind you, he’s quite something, he never looks down. When he holds out his arms to me and says, ‘Carry Nanny,’ he knows what he wants, I’m telling you, and you can’t expect him to give up. He’s right there up against my leg, patiently waiting for me to give in. And he gets his way, I give in, of course I do. I carry him. Sometimes I even carry him around for hours. He’s so cute, my little one, and so sensitive. If it makes him feel better, I carry him – why wouldn’t I? He’s calm with me and very affectionate; he hides his face in my neck, rests his head on my shoulder. You should see what life is like here: the children have no right to anything, they’re herded like animals upstairs, and even then, to the back of the house. They hardly recognize their own parents when they see them at teatime or at Sunday lunch. The parents call them down to give a toothy smile for their guests, shake their hands as if they’re strangers and give them back to me just as quick, as if they had the plague. Ah, with these people there are no displays of emotion, you can rest easy. When I think of Mr Bacon’s affection for his dogs, the petting he gives them.

To come back to the story about the boots, I was furious, you see, I was forced to borrow boots from the stables until the following day. And those grooms, I don’t like them at all, oh no. They’re brutes and smart alecs. Always snotting their sleeves or squatting behind bushes. And when you rub their noses in it, they dare to say it’s the dogs. Well, they wouldn’t dare pull that one with me. I was brought up in England, in Cornwall, in the hamlet of Burlawn, and I’m not going to learn manners from the Irish. In fact, I found it hard to get used to Ireland at first – the change of air and all that – but the wages on offer were more than fair, there was no question of being picky. I said to myself, they want a nanny, I’ll be the nanny, why wouldn’t I be? As long as they don’t expect me to be a wet nurse – I’m still a maiden! – everything will be fine.

I haven’t told you about Cannycourt House. Lord, it’s grand and smart, and such a luxurious house! Eighteen rooms, plus the outbuildings. Ah, what a change of scene for me. Yet when I arrived in 1911, I’d already been a maid in London for twenty years, and yes, Miss Lightfoot was no longer a spring chicken. You can imagine, I was almost the same age as Mr Bacon – ‘the Captain’, as we call him – well, retired Captain, now his hobbies are hunting and racehorses. Some Captain he is, a bloody puritan, more like, who laughs when he burns himself! He forbids everything in his house, no alcohol, no this or that. But it doesn’t stop him from being as mad as a Christian, a real beast, always ranting, spitting his complaints, spitting his venom at his sons and at the whole world. It’s like hell coming out of that mouth, out of those entrails. Rotten from the inside out. And yet the devil looks good, swan-like in his elegance, always with his tie around his collar, and strong as an oak with it. A great swindler when you get to know him. This man has every fault in the world. He’s got a temper, he’s a brawler and he bets his money at the races on top of everything else. When he’s not gambling. Well, when I say his money, I should say Madame’s dowry, mind you, that’s why he married her, the bugger. He sucks her dry, even puts her into debt. Ah, what a wonderful marriage, when you see Madame, who is so young, with that sinister old fox, what a waste. It’s easy to understand why her cousin didn’t want him. You have to have strong nerves to put up with that animal. He’s a real despot, everyone stands to attention in front of him, as stiff as soldiers, waiting for the orders to be issued, for things to snap if they don’t respect his commands and the strict timetables he imposes. A hurricane, a storm. Always bellowing or biting, bitter (that’s putting it mildly) and bad. Bad. Nobody does anything good, anything worthwhile. They’re all a bunch of losers, with the exception of His Honour the Captain and His Honour the horse trainer. None of his comrades, even those from the racecourse, last long; he always ends up arguing with them or they leave, worn to the bone. He becomes all the angrier for it. Angry with them, with everyone, with God and his creatures. When he feels like it, when he bumps into a chair and hurts his toe, when he finds his boots badly polished, the blood goes to his head above his moustache and then nothing stops him, except his own tiredness when the sack of malice is emptied and his victim lies inert. And Madame is regally calm and unflappable. As long as the house is ‘im-ma-culate’ and he lets her entertain all her friends in their beautiful dresses and cloche hats, she couldn’t care less. How do you expect her to deal with an animal like that anyway? You’ll say to me, with what I’m telling you, that his ears must be burning pretty badly right now, don’t you think? Ah, I say good enough for him, he earned it all.

You know, when I took up my job at Cannycourt House, I had no idea where I was going, what was happening in Ireland. You see, I was far more interested in George V ascending the throne than I was in their squabbling or in their potato stories. Of course, in London, I’d been told the story of the dimwit who’d blown himself up trying to blow up Westminster Bridge, and we’d had a good laugh about it, but that was all. Nor did I know anything about the English in Ireland who had settled in County Kildare, or on large estates where they bred their racehorses. When I arrived, I can still see the wife saying to me: ‘Miss Lightfoot, we are the enemy here.’ Oh, yes – Protestants, and English ones at that. The worst category of all. Houses looted, burnt down, including the stables with the horses in them. Everything up in smoke. And do you think the Sinn Féin boys mind? A trip to confession the following Sunday and it doesn’t seem to bother them any more. Ah, their God is accommodating. He doesn’t look too closely at the pedigree of his flock. At Cannycourt House, we’re like deer on the opening day of a hunt, we can’t cross a room without glancing from side to side. Her ladyship keeps saying to me: ‘Miss Lightfoot, never turn your back on the windows and, for pity’s sake, keep the curtains drawn.’ Talk about living in a castle. We live like sheep next to a slaughterhouse. Madame is even convinced that one of the servants in the house (Mr Moody, not to name any names) is a freedom fighter disguised as a butler and that it is down to him that we owe our survival (more precisely, down to his love for the women of the house). You can understand what it’s all about. In other words, you have to watch out for the neighbours.

When you leave the estate, it’s the same story: you can’t talk to anyone, so to speak, and you must be careful not to attract attention or to give out any compromising information. The Captain terrorizes the children with this, constantly talking about the rebels and saying to them, ‘If they come tonight, don’t tell them anything.’ As if the children were a threat, as if they were going to give him up, to make him pay for his wickedness, this torturer of a father. He adores making them cry. Nothing makes him happier than Francis’s tears and his laboured breathing in bed. When Francis is in a bog of sweat, choked with asthma and coughing uncontrollably, as white as a sheet, his father calls him a wimp. In truth, it’s his horses he’s worried about. His thoroughbreds. Ah, they count more than anything else, he wouldn’t risk having them whipped by those bloody grooms like his sons. That would cost him too much.

To get back to Ireland, there are some frightening things happening in the neighbourhood: Englishmen buried up to their necks in sand, waiting for the tide to finish the job, roads booby-trapped, potholes full of bombs. In the forests around us, the birch trees are festooned with Sinn Féin flags, green, white and gold, taunting us and threatening reprisals. One evening, Francis and his grandfather got caught in the Bog of Allen, in a pro-independence ambush. They got out of the car at the last minute and they heard the rebels’ voices in the distance, congratulating themselves on their capture and shouting the news to each other. ‘Englishmen caught!’ Beams of light pierced the darkness. Francis held tight onto Grandpa Supple, Granny’s new husband. The old man led him on a wild goose chase; they didn’t know how many rebels were after them. The asthmatic boy took to his heels, running as fast as his legs would carry him to escape the monsters with their yellow night-time eyes. The shadow of the hangman’s noose hovered over the countryside, and it seemed to him that the grass and trees were following him, that the hares, foxes and badgers were working for the terrorists, digging holes into which he was sure to fall. At last, a light in a window, the door they are pounding on with their fists is opened. They breathe a sigh of relief. But believe it or not, the owner is armed to the teeth. He questions them, warily, with his gun on the table, interrogating them about their background, testing their accents. Then, reassured by the fact that they are as English as he is – with their cut-glass accents – he ends up serving the grandfather a fine old whiskey and offering them a bed for the night. Things like that leave a lasting impression on a child, I can assure you. Decades later, when a light bulb blew in his London studio, Francis still thought it was the IRA.

The violence in Ireland frightened him terribly, gave him asthma attacks, and had him gasping for breath. The violence was compounded by the horses and dogs kicking up dust. Sheep, dairy cows, pigs, poultry – living in the middle of a livestock farm is a daily nightmare for an asthmatic, a land of beasts where their pelts were more dangerous to him than their fangs. At Cannycourt House, the long corridors led straight to the stables, where the animals ruled supreme and got the better of all of us, especially Francis. Look at him fighting like a hero through the candle smoke, and the inhalations of burnt powder he breathes in, the Potter cure for asthma doing little to help. See him suffocate and resuscitate with every breath, his face flushed with each dose of morphine. Watch the child live without air, like a fish out of water. And because of his asthma, Francis couldn’t go to school. His education was pared back to the bone – Lionel Fletcher, the village vicar, was his tutor. Oh, he wasn’t a bad chap; on the contrary, he was more of a bon-vivant, drank a lot more than holy water. He looked after his little flock of English people in Ireland, jumped on his horse and went off to hunt the little red fox in his den. He really wasn’t a bad man, not the bible-thumping, craw-jamming kind. He was very kind to Francis, patient and quite devoted – it pained him to see the Captain bully Francis as he did, calling him a girl in public – but I couldn’t say that he taught him anything … He claimed that Francis was already too old for Latin and Greek, ‘You have to learn it in the cradle or not at all,’ he told him. How do you respond to that? God forgive me, but I always thought that he felt he had better things to do and that he was quite the lazybones. In spite of everything, I have to admit that he gave him a taste for reading. After Reverend Fletcher had come and gone, Francis devoured everything: he spent his days lying in front of his mother’s bookcases, large leather volumes in his hands. You know, he was the only one who didn’t go to school, who didn’t have any friends apart from his cousin Diana. It wasn’t easy for him. Not to mention his parents’ constant hither-and-thithering. Mr and Mrs Bacon were on the move all the time, changing places non-stop. As soon as they arrived in London, they were already planning to go back to Ireland, over and back all the time. How do you expect children to grow up properly in an atmosphere like that?

During the war, for instance, we were in London again in 1914, accompanying the Captain, still convinced that he could play his part. He saw himself as a hero. He was well into his forties then, but he still thought he was a young man and wanted to pin more medals on his jacket. Naturally, his reputation preceded him and followed him around like a bad smell – the army promptly put him with the other angry buggers on desk duty. And who does he take it out on, I ask you? Who does he blow up at in the blink of an eye? The rest of us, of course. Everyone gets it: his lady wife, the servants, the children. All those who find themselves in the crosshairs of his hatred, wading through puddles of his bile. All of us, starting with little Francis. ‘The weakling, the coward, the girly’ – that’s the greatest insult he throws in his face. As if the war weren’t enough, with the power cuts, the searchlights sweeping the sky for enemies and bombers. Francis can’t sleep at night. ‘The girly,’ as he calls him, spends nights with his eyes wide open, as if his eyelids were clamped open with pliers, or worse, as if he had none at all. Two immense, bulging blue globes, staring at the wallpaper, afraid the wall might collapse. Nights spent terrified by his adversaries, with one raining bombs outside and the other ready to pop out from behind his door. Terrified by the monster at large in the house, against whom he can do nothing. It has to be said that the cursed Captain chose the right moment to bring us back to London, in the middle of the cataclysm. That was some voyage. And as soon as the war is over, just as Francis is getting used to London, to galloping alongside the Serpentine, watching the gardeners raking Hyde Park as if it were God Almighty’s goatee, we have to go back to the land of the papists. Ah, I was really not happy. All the more so as Sir chose to go back at a time when those crazy Irish were acting up, when everyone was still thinking about the Easter Rising. Well, it’s true that that didn’t last long. It has to be said that the twits weren’t very bright. They took over the General Post Office, the Four Courts and Jacobs Biscuit Factory, and they thought they were going to win. I can just imagine the biscuit-makers hiding under the dough to duck any pot-shots – that must have been a laugh. They caused havoc for six days, the scoundrels. It’s true, they might as have well been hanged for a sheep as for a lamb. In any case, the end is the same, the rope placed snugly between ear and jaw, the vertebrae snapping on the way down – crack. Or in their case, bang as they were shot. But that wasn’t enough for them. Oh no. Their pals continued, good-oh. And after independence, they went for each other’s throats. You can imagine the mess, one war was over and we headed for another one. None of that stopped the Captain from going hunting. Nor did it stop him from forcing his ‘sissy son’ from going with him. Riding his pony until he turned blue in the face, to the point of passing out while his father shot a rifle, showing off his skills to his son and executing a vixen in front of her cubs. Dreadful! When they returned, I could hear my Francis wheezing in the distance, louder than a horse after a race. Sir delivers Francis to me choking, inert, a bundle. ‘Don’t worry, Miss Lightfoot, he’ll get used to it in the end.’ The torturer is quite pleased with himself, convinced that he’s toughening him up. The truth is, he hates the child. Like he hates his eldest, in fact. Now there are five of them, he only cares about his daughters and the youngest boy, who has the same Christian name as him. Mind you, this doesn’t make young Edward any happier, to say the least. He won’t escape the curse that strikes the boys in the family, who draw their last breaths before experiencing their first shave.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. As far as Francis is concerned, no matter what his parents do, they eventually realize that with his asthma he can’t do much on an estate like this, in the middle of the countryside, surrounded by horses. Apart from being bored for hours on end, watching from the window as the neighbouring cavalry manoeuvres, the handsome English soldiers in their red jackets twirling their horses and blowing their bugles at the top of their lungs. Apart from dreaming, and contemplating the landscapes, the bog populated by flocks of birds – plovers and snipe. He knows them by heart, draws them in incredible colours and offers them lovingly to his mother. To Madam, always as cool as a cucumber, and who couldn’t care less – too busy she was with her tea parties and dances. She takes the drawings distractedly with one hand and puts them down with the other, forgetting them there on a corner of her desk. Sometimes she brings them over to the fireplace, which opens its mouth wide. The heartless hearth devours the sheets, burns the landscapes and with them a piece of the soul of the child whose fingers had painstakingly brought them to life. He bites his tongue. Madam isn’t mean, but she hardly ever thinks about the children. She entrusts them to me and doesn’t give them any more thought, that’s all. The little ones sense it, you know. Francis questions me, he’s worried about what’s happened to the drawings he sweated over for hours – well, do you know what I do? I lie to him. I tell him that his treasures are carefully stored by Madam in the library, between the gilded bindings of the most precious books. Yes, I lie through my teeth to him so as not to upset him – what else can I do? I’m afraid the boy isn’t fooled. He’s too clever to be fooled. He stares at me, with his big round saucers of eyes, they speak volumes for him. He has that terrible, hopeless look of his mother’s that makes my stomach churn.

Thank God for Granny – have I told you about Granny? Granny Supple, Madam’s mother. She’s an astonishing woman, I’d even go so far as to say stunning. Ah, now that word is just for fun, she’s not stunning. She does have great neck though. She’s on her third husband – she’s game for anything! Of course, she is half French, maybe that’s why. It’s true that the first husband, the judge, Mrs Bacon’s father, died very young. He suffered from asthma too, poor fellow. And then, sometime later, she brought back a first-rate bastard, Walter Bell – master of the hunt – he was really mad wild, and not just when he was hunting if you know what I mean. Francis told me all about it, and it’s not a pretty tale. When he wasn’t out hunting, the blackguard took his predatory instincts out on his pets, ripping the claws off cats in his spare time and throwing them to the dogs to whet their hunting appetites. So much for being a gentleman. He was a foolish, abominable man. One day, one of the moggies managed to escape and took refuge in a tree. Francis saw the dreadful man put a rope around the cat’s neck and shake it until it went limp. Then the horrid man wandered into Granny’s house, dragging his trophy behind him, bouncing it down every step of the stairs, as the servants and the whole house looked on in horror. The horrible master of the hunt also had a legendary temper and whipped the children, whom he could barely tell apart from the animals in his care – they were all at the mercy of his bloodthirsty desires. Even Granny was afraid of him, even though she was no lily-livered gal. She would closet herself away whenever he was around. She would hide in the wardrobe with Francis in his bedroom. The boy didn’t want to go there any more. Imagine that! No, the situation had really become unbearable. Especially as the caveman was also a drunkard, and the drink made his ruthless tendencies even worse. Finally, what had to happen happened. Granny summoned her strongest servants and took her courage in both hands. She showed him the door and promptly divorced him. The bird of ill omen roamed the woods for several weeks, returning at night, soaked in whiskey, to sing under her windows. In the end, he disappeared. He went back to where he came from, to his childhood home nestled in the Newcastle countryside in the hills in the north England. He won’t be missed. Farewell and good riddance to the bandit.

Granny’s third husband is Grandpa Supple, Chief Constable of the Royal Irish Constabulary in County Kildare. His job is to keep the peace in Ireland. He’d be a real catch for the rebels if ever he fell into their clutches. Luckily, he always eludes them. One night they almost got him; you could say that they came a bit too close for comfort. One of the bastards tried to shoot him while he was sitting quietly in the living room. But Granny had taken off her wig and, as he couldn’t make out which of the two heads above the sofa was the right one, he didn’t dare shoot. Talk about a miraculous escape. Grandpa Supple always has luck on his side, the devil’s own luck to put it mildly. Since then, Granny has had sandbags put in front of the windows just in case, big bags of sand to cushion any bullets that might try to hit her in her incredible house.

Granny’s house is incredible, round like a tower. Francis really likes it and often stays there. He gets on well with Grandpa Supple, his new grandfather (we’ve definitely drawn a winner there), but the one he cherishes most of all is Granny. I don’t blame him, she’s irresistible, so elegant with her tailored jackets and waist-length pearl necklaces. And she’s a born entertainer. When they’re together, you’d swear they’re the same age. Not one to outdo the other. They laugh their heads off. They tell each other their stories, Granny does her imitations – ah, you should see them! They have so much fun, I’m always afraid of cramping their style. I make myself as inconspicuous as a fly on the wall and muffle my laughter at their nonsense. Francis listens to Granny’s tirades, making fun of the Captain, taking revenge for him on his father. She has no scruples, she is as free as a bird (never known a Protestant like her), and eagerly unleashes her sharp tongue on the back of ‘the blunderer, the adventurer who took advantage of my daughter, the low-class swindler’. She recounts the Captain’s ridiculous adventures, says he’s too big for his boots, says he plays God when he’s not worth a damn. And that’s just the warm-up, the appetiser before Granny takes off, before Granny goes off the rails. Granny always goes off the rails, that’s one of her strengths. Her lips slither without ever sliding, they skitter and always end with ‘the flat of my arse’, which makes Francis roar with laughter and sends him rolling off the sofa onto the carpet. He is always in such good spirits with her, it’s unbelievable! His cheeks are flushed pink and his features are relaxed. His face is washed clean of his fears, and he is a child again, a little man.

Granny is also quite the seamstress and an embroiderer beyond compare. She has nimble fingers; you should watch her make her large samplers from scratch. Francis observes every detail, admiring the colours and sophisticated shapes. Sometimes she teaches him, when no one is looking. She teaches him behind the servants’ backs – those rascals might tell Sir. The Captain has ears and eyes everywhere and demands to know everything about those under his control. He keeps a record of people’s faults, and builds up piles of misdeeds so that he can use them later and punish the children at their first misstep. So let’s not mention embroidery for Francis. He thinks he’s never enough of this or that, and calls him a faggot at every hand’s turn. By teasing him constantly, Mr Bacon ended up getting what he didn’t want. Hoist by his own petard.

Let me tell you this. One day Granny organized a party – Granny is a real lady, she organizes sumptuous parties with all sorts of crazies, parties that get the neighbours talking. For this particular one, she decided that fancy dress was the order of the day. Francis and I were already at Granny’s. I saw him going through his grandmother’s wardrobe, looking for something to wear. Suddenly, his eye alights on a short, fringed dress, a halter-neck flapper dress embroidered with sequins. Granny alters it for him, adjusting it for his slim waist. The fabric matches the feathered headband around his forehead and the lipstick he carefully applies in front of the gold mirror in the dressing room. I pass by him as he comes downstairs. With his boyish haircut, he is almost unrecognisable. ‘Look at that gorgeous blonde girl!’ I say to him. He kisses me, grinning from ear to ear, and gracefully descends the stairs, his patent pumps leaving tiny prints on the carpet with each step. When he enters, he causes quite the stir, with all the English gentry coming to see him, ladies dressed up as queens brushing him with their gloves, laughing between two puffs on their cigarettes, gentlemen in shimmering capes approaching him like wolves. All come to admire the flamboyant young man in his evening gown. The boy who looks like a girl. The costume fits his slight figure so well. His presence spreads a feeling of confusion through the room. It’s like being at one of those Irish parties where the men wear their regimental kilts and, knowing they are naked underneath, they scare the women as much as they scare themselves, aware that they are there for the touching. Francis is so young, barely fourteen. I know exactly what he’s doing, I know him – he’s acting. For once, he is doing what he wants. He’s entertaining the crowd. He’s imitating Granny’s manner, which he admires. So much the better, really. He’s usually so shy, but in this new rig-out, he gains confidence beneath the make-up. His movements are freer, and he even tries out a few steps of the Charleston on the dance floor. The flowing dress glides over his moving legs, his knees cross. I can’t believe it. The guests applaud him, gazing enviously at his young body showing itself off, taking advantage of the disguise to reveal what he really is. I’ve known for a long time, as you can imagine. What’s the big deal? What of it? He’s a wonderful child. I’m telling you, I’ve seen a lot of funny ones, there are no two like him, not one who even comes close. He sees everything, he feels everything, he understands without being told. I’ve never seen anyone like him. He doesn’t do anything like everyone else, and that’s true, he always has an idea in the back of his head, and always has a clever remark to make. He’s passionate about beautiful things. He just likes to be liked, that’s all, and that’s what his father doesn’t understand.

As Francis dances, I recognize the Captain at the back of the room, dressed up in priestly robes. He leans against an armchair, frantically opening and closing his fists, following every movement, every nod of Francis’s head as he shakes his clip-on earrings. When the band stops, I can see the Captain motioning to Mrs Bacon at the other end of the room to follow him, indicating the exit with a jerk of his chin. I know exactly what Francis will be facing when he returns tomorrow. What I wouldn’t do to prevent it if it were in my power! Do you want to know what’s in store for him? Well, I’ll tell you. It pains me to talk about it, but the truth has to come out sooner or later. The next day, at the stroke of ten, when Francis returns home, the Captain does what he always does to him – as soon as he finds an excuse, an opportunity to make him pay. He grabs him by the arm and leads him away in silence. He leads him to the stables: the punishment that awaits is one the poor child knows only too well.