9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

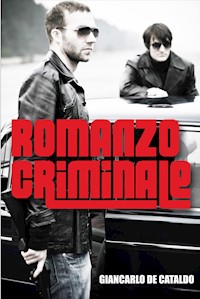

It is 1977. A new force is terrorising Rome - a mob of reckless, ultraviolent youths known as La Banda della Magliana. As the gang ruthlessly take control of Rome's heroin trade, they begin an inexorable rise to power. Banda della Magliana intend to own the streets of Rome - unless their internal struggles tear them apart. Based on Rome's modern gangland history, Romanzo Criminale fearlessly confronts Italy's Age of Lead: war on the streets and terrorism, kidnappings and corruption at the highest levels of government.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

First published in Italy in 2002 by Giulio Einaudi editore S.p.A.

Published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2015 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Giancarlo de Cataldo, 2002 English translation copyright © Antony Shugaar, 2015

The moral right of Giancarlo de Cataldo to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Antony Shugaar to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 0 85789 372 7 E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 373 4

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street LondonWC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Tiziana

Special thanks go to Bruno Pari, ‘er più de li macellari’, for his lessons in ‘romanità’, and to P. G. Di Cara for the quote from Bernardo Provenzano and his review of the dialogue in Sicilian dialect.

The restriction of bloodshed to a minimum, its rationalization, is a business principle.

Bertolt Brecht, Notes to the Threepenny Opera

I urge you always to be calm and righteous, fair and consistent, may you successfully benefit from your experience of the experiences you suffer, do not discredit all that they tell you, always seek the truth before speaking, and remember that it is never enough to have one piece of evidence in order to undertake a decision. In order to be certain in a decision, you must have three pieces of evidence, and fairness and consistency. May the Lord bless you and protect you.

Bernardo Provenzano, July 1994

Table of Contents

Prologue, Rome, Now

PART ONE

Genesis 1977–78

Alliances February 1978

Business, Politics March–April 1978

Inside and Out April–July 1978

Settling Scores August–September 1978

The Idea January–June 1979

Keeping Up With the Times July–December 1979

Controlling the Street 1980

Death of a Boss 1980

PART TWO

Hubris, Dike, Oikos 1980–81

Rivers of Blood Winter–Spring 1981

Rien ne va plus 1981

The Smell of Blood January–April 1982

Si vis pacem, para bellum 1982–83

Turncoats 1983

Other Turncoats 1983

PART THREE

Everyone Behind Bars 1984

Solitude, Disamistade 1984

The Past and the Future 1984–85

Epidemics 1985–86

Cliffhangers, Escapes 1986

Individuals and Society 1987

The Certainty of the Law 1988

Liberty 1989

Dandi’s Blues 1990

Epilogue Rome, 1992

Closing Credits

Prologue

Rome, Now

HE CROUCHED BETWEEN two parked cars, curled into a ball. He covered his face as best he could and waited for the next blow. There were four of them.

The little man was particularly vicious; a knife scar ran the length of his cheek. Between assaults, he traded witty observations with a girlfriend on his mobile phone: a running commentary on the beating. Fortunately, they were punching blindly. This was their idea of fun. They’re young enough to be my own kids, he thought. Except for the African, of course. A gang of wild, reckless lowlifes. Only a few years ago, he thought, if they’d so much as heard his name, they would have just shot themselves in the head to avoid tasting his vengeance. A few years ago. Before everything changed. It had been a brief, fatal moment of carelessness. The hobnailed boot caught him right in the temple. He slithered down into blackness.

‘Time to go,’ ordered the little man. ‘I’d say this one’s not getting back on his feet!’

But he did. It was already dark by the time he picked himself up. His ribcage was in flames, his thoughts were muddled. A short way up the street there was a water fountain. He washed off the dried blood and drank down a long gulp of water that tasted of iron. Now he was on his feet. He was walking. On the street, cars went by, stereos blasting, while knots of young men toyed with their mobile phones and laughed scornfully at his lurching gait. The windows were lit by the bluish glow of thousands of television sets. A little further on: a brightly lit shop window. He eyed his reflection in the glass: a man hobbling in pain, coat torn and matted with blood, thinning greasy hair, rotten teeth. An old man. Look what he’d become. A siren sailed past. Instinctively he flattened against the wall. But they weren’t looking for him. No one was looking for him now.

‘I was with Libano!’ he murmured, almost incredulous, as if he had suddenly come into possession of someone else’s memories. They’d taken his money, but the lowlifes had overlooked his passport and ticket. As well as his Rolex, sewn into an inside pocket. They were having too much fun to search him thoroughly. A smile flickered across his face. They’d be breaking their teeth on some tough bread crust, no question.

Passengers wouldn’t be called for boarding for another three hours. There was enough time. The gypsy camp was about half a mile away.

The African was the first to see him coming. He stepped over to the little man, who was making out with his girlfriend, and told him that grandpa was back.

‘Didn’t we kill him?’

‘How would I know? But here he is!’

He strolled easily across the piazza, looking around him with a foolish smile, as if begging pardon for the intrusion. The other lowlifes glanced idly at him as he went by, and then returned to their own business.

The little man told the girl to go for a walk, and then stood waiting, arms folded across his chest. The African and the two others – a very tall hooligan with a pockmarked face and a fat thug with tattoos – flanked him on either side.

‘Good evening,’ he said. ‘You’ve got something that belongs to me. I want it back!’

The little man turned to the others. ‘He hasn’t had his fill!’

They laughed.

He shook his head and pulled out the piece. ‘Everyone flat on the pavement!’ he said in a grim voice.

The African reared back. The little guy spat on the ground, unimpressed.

‘Sure, let’s play ring-around-the-rosy! Who are you trying to scare, with that pop-gun!’

He looked down apologetically at the little .22 calibre semi-automatic that the gypsy had given him in exchange for the Rolex.

‘You’re right, it’s small … but if you know how to use it …’

He fired without aiming, and without taking his eyes off the little man. The African dropped with a howl, clutching at his knee. Suddenly, there was a deep silence.

‘Clear out, everyone!’ he ordered without turning around. ‘All but these four!’

The little man waved his hands in the air, as if to placate him.

‘All right, all right, we’ll work this out … But you just keep cool, right?’

‘All of you, down on the ground, I said,’ he repeated quietly.

The little guy and the others knelt down. The African was rolling and keening in agony.

‘I gave the money to my girl,’ the little man snivelled. ‘Let me call her on my mobile phone, and she’ll bring it back, all right?’

‘Shut up. Let me think …’

How long could it be until boarding time was called? An hour? A little longer? The girl could be back here in a couple of minutes. He’d have his money back. Venezuela awaited him. It might take some time and effort to fit in, but … it shouldn’t be that difficult, down there … right. The smart thing would be to relent, at this point. But when had he ever done the smart thing? When had any of them ever been smart? And then, the little man’s fear … the smell of the street … Hadn’t all of them always lived just for moments like this?

He leaned down over the little man and whispered his name into his ear. The little man started trembling.

‘You ever heard of me?’ he asked softly.

The little man nodded.

He smiled. Then he delicately lodged the barrel of the gun against the little man’s forehead and shot him between the eyes. Indifferent to the sobbing, the sound of running footsteps, the approaching sirens, he turned his back and aimed his gun at the bastard moon. With all the breath he could muster, he shouted:

‘I was with Libano!’

PART ONE

Genesis

1977–78

I

DANDI WAS BORN where Rome still belongs to Romans: in the apartment blocks of Tor di Nona.

When he was twelve, they’d deported him to Infernetto. Written on the eviction order, signed by the mayor, were the words: ‘Reconstruction of decrepit buildings in the historic section of central Rome.’ That reconstruction had been dragging on for a lifetime now, but Dandi never tired of saying that, one day, sooner or later, he’d move back to the centre of Rome. As a boss. And everyone would bow to him as he went by.

But for now he was living with his wife in a two-room flat with a view of the huge gasometers, the Gazometro.

Libano walked there from Testaccio. It wasn’t far, but August perspiration was pasting his black shirt to his virile, hairy chest. As he walked, he felt a growing fury at the little delinquent.

Dandi opened the door with a bewildered expression on his face. He was dressed in a red polka-dot dressing gown. He’d once chanced to read a few pages from a book about Beau Brummel. Ever since, he’d been a sharp dresser. And that’s why he was known as Dandi.

‘I need the motorcycle.’

‘Quiet. Gina’s sleeping. What’s up?’

‘They stole my Mini.’

‘So?’

‘The duffel bag was inside.’

‘Let’s go.’

The hot scirocco wind was actually agreeable, as they rode out on the Kawasaki. They hurtled down the road, until they reached the Magliana water-pumping station. There they parked the bike in front of a badly rusted iron security shutter and set off on foot into the big meadow. The hut stood between an abandoned wreck of a building and a warehouse full of junk. The door was bolted shut; it was dark inside.

‘He’s not back yet,’ decided Libano.

‘Who is it?’

‘Some idiot. The nephew of Franco, the barkeep.’

Dandi nodded. They sat down on an old hollow tree stump. Dandi pulled out a joint. Libano sucked down a couple of puffs and passed it back to him. This was no time to get wasted. For a while, they sat in silence. Dandi closed his eyes and savoured the relaxed pleasure of the hash.

‘We’re wasting time,’ said Libano.

‘Sooner or later the motherfucker has to come back home.’

‘That’s not what I’m talking about. I mean, in general: we’re wasting time.’

Dandi opened his eyes. His partner was restless.

Libano was short, dark and bluff, and his nickname – Lebanon – was a tribute to his Levantine appearance. He was born in San Cosimato, in the heart of Trastevere, but his people were from Calabria. They’d known each other all their lives. They’d run a gang of kids when they were small, and now they were an enforcement squad.

‘I’m thinking about the baron, Dandi.’

‘We’ve talked about this a hundred times, Libano. The time isn’t right. There’s too few of us. And it belongs to Terribile. There’s no way he’d okay it.’

‘That’s exactly it, Dandi. I’m sick of asking permission. Let’s just do it.’

‘You may be right. But we’re still outnumbered.’

‘For now … That’s true for now,’ Libano ended the discussion thoughtfully.

A fat yellow moon had taken possession of the horizon.

Libano was right. They needed to think about setting up operations on their own. But a squad made up of four youngsters didn’t have much of a future. Organization. How many times had they talked about it? But how to get started? And who with?

A dog started barking.

‘You hear that?’

Footsteps on the asphalt. Whoever this was, he wasn’t trying to hide. They both crept over to a pile of truck tyres. The young punk, skinny and misshapen, lurched along as he walked. When he was within range, they nodded in agreement and moved fast.

Libano grabbed him from behind, pinning him so he was helpless. Dandi kicked him hard in the stomach. The punk whimpered and slumped to the ground. Libano plunged the punk’s face into the dry earth, pulled out his revolver, and planted the muzzle at the base of his neck.

‘You know who I am, you idiot?’

The punk nodded furiously. Libano pulled his gun away.

‘Get up.’

The punk got to his knees.

‘He stinks like a goat,’ said Dandi in disgust.

‘That’s the smack. He’s wasted. Get up, I said.’

The young punk struggled to get to his feet, flailing. Libano smiled.

‘I promised your uncle I would take it easy on you, but don’t test my patience. Answer yes or no, don’t say anything else.’

The punk stared at him, dazed and confused. His face was covered with red sores. Dandi kicked him once in the jaw.

‘Yes or no?’

‘Yes.’

‘Good,’ Libano continued. ‘You stole the Mini in Testaccio, right?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did you look in the boot?’

‘No.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yes.’

‘Lucky for you. Where’s the car now?’

‘I don’t have it anymore …’

Dandi limited himself to a sharp smack to the nape of the neck. The punk started whimpering. Libano sighed.

‘Did you sell it?’

‘Yes.’

‘To who?’

The punk fell to his knees again. He couldn’t say. Those people were dangerous. They’d kill him.

‘Bad situation, eh, kid?’ said Libano. ‘If you talk, they’ll shoot you. And if you don’t talk, we’ll shoot you …’

‘Libano, once I saw a Western—’ began Dandi.

‘What’s that got to do with this?’

‘You’ll see, you’ll see. There was a horse that had been injured, poor thing, it was on its last legs … and the owner didn’t know what to do … Poor animal, he looks up at his master with these big pitiful eyes … Why do I have to go on suffering, it was saying …’

‘Aaahh! Now I get you! So finally he puts the horse out of its misery, right? Bam!’

‘Exactly!’ said Dandi.

‘But … but, Dandi, look, there’s something I don’t understand.’

‘Then ask me, Libano!’

‘The horse in the film, you said it was injured … And this kid, from what I can see, he’s perfectly healthy …’

Dandi shot the punk in the knee. The punk grabbed his leg and started screaming.

‘Take another look, Libano!’

‘You’re right, Dandi. He’s hurt badly! He’s in terrible pain! What do you say, should we help him out? Put him out of his misery?’

The punk talked.

II

NOW FREDDO – ITALIAN for ‘cold’, a reference to his icy composure – had the Mini. Libano knew nothing about him, but Dandi had crossed paths with him once or twice. He was a serious operator, not much of a talker, and he had a certain amount of experience with post offices. He’d been arrested once for extorting money from a chef, but he’d been acquitted after the victim retracted his testimony. A trustworthy individual, in other words.

Still, they had their guns at the ready when they kicked in the door of the abandoned warehouse behind the restaurant Il Fungo.

Libano found the light switch. Aside from a strong smell of petrol, there was only the bodywork of a stripped Fiat 850 and, behind a plate-glass window that had seen better days, what looked like a small accountant’s office.

They stared at one another in dismay. It had seemed at the time that the punk was telling the truth, but you can never be sure about that kind of thing. Libano was starting to regret the partial mercy he had shown, when they heard a noise behind them.

They turned around slowly. There were four of them. They must have waited for them in the street, concealed somewhere, perhaps inside a car. Libano scanned them rapidly: two short men, dressed in gym shorts and T-shirts, both with the same brutish face, like a pair of badly formed twins; then a bearded man built like a wrestler, with one eye looking towards India, the other looking at America; and in the middle, the youngest of the group – dark, curly hair, skinny as a rail. Freddo. Practically a child. A penetrating glare. Focused, determined.

Meanwhile, Dandi studied the arsenal: three semi-automatics – and Freddo was holding a long-barrelled revolver. A Colt, .38 calibre. A handsome beast: reliable, traditional.

‘How’s it going, Freddo?’ asked Libano.

‘We were expecting you.’

A tight situation. Clearly not a good one. The other guys were feeling relaxed and in control. If not, they’d have opened fire immediately. Freddo seemed perfectly capable of controlling his men. Libano decided it was no accident that he’d picked up that moniker, and flashed him a vaguely friendly smile. Freddo barely moved his head, and the cross-eyed guy strolled away unhurriedly towards the office, careful not to wander into the line of fire. A minute later, a boxer’s equipment bag was tossed to the floor at Libano’s feet. The duffel bag in question.

‘Open it up and take a look. It’s all there. Four Berettas, two Tanfoglios, the clips and the ammunition,’ said Freddo.

‘I trust you, Freddo. I’ve heard a lot about you.’

‘You must be Libano. It’s too late for the Mini, though. Sorry about that.’

He said it with an odd sneer. That must be what passes for a smile with him.

‘No big thing. It was insured.’

What tension was still in the air subsided in a collective burst of laughter. Everyone lowered their weapons. Dandi suggested going for a drink at the Re di Picche, a bar named after the King of Spades. Libano asked to use the phone, if there was one. The cross-eyed wrestler escorted him into the office. From there, he called Franco the bartender and told him where he could go get his nephew.

‘He’s still all in one piece, relax. He might walk with a limp now, but he got off easy.’

Freddo introduced the Buffoni brothers and Fierolocchio, the cross-eyed guy. The gambling den, the Re di Picche, was winding down for the night, aside from the bartender in a bow tie and a couple of wrecked-looking whores with bags under their eyes. They ordered a bottle of champagne and a deck of cards, and killed a few more hours playing a listless game of zecchinetta. There was something in the air, something that was bound to come out sooner or later. They just didn’t know where to begin. Dandi and the Buffoni boys were ready to call it quits by the time the sun came up. Fierolocchio had fallen asleep, his head on the card table. Freddo offered to give Libano a ride to Trastevere. They climbed into his VW Golf hatchback, and Libano tested the ice.

‘This Re di Picche strikes me as a real shithole.’

‘You can say that again.’

‘Who owns the place?’

‘Officially it belongs to some woman named Rosa, a geriatric whore. But the real owner is Terribile …’

‘Terribile this, Terribile that … I’m getting sick of tripping over this fucking Terribile every time I turn around. Senile old fuck without an ounce of brains in his head. If he had people like us working for him, we could turn a dive like this into a goldmine …’

Freddo said nothing, apparently concentrating on his driving. But there was a gleam in his eye. Libano decided to double down.

‘Just think, Freddo: a few poker tables, a dealer, a nice fat ante, high table stakes, but strictly for a select clientele. A cosy little spot. Some girls – the right kind of girls, not those worn-out hookers. A barman who knows how to pour … What could you pull in with a place like that, eh? Think about it. How much a month? How much a week?’

‘A lot of cash. But you’d need at least that much just to get started.’

‘Anything’s possible. All you need is to find the right people.’

Freddo slammed on the brakes at the corner of Viale Trastevere and Via di San Francesco a Ripa and glared at him in his angry, inscrutable way.

‘What do you have in mind?’

‘A kidnapping.’

‘Who?’

‘Baron Rosellini. The one who runs horses.’

‘Why him?’

‘He’s methodical. Sticks to a routine, follows a schedule. Piece of cake.’

‘Kidnappings are never a piece of cake. How many men do you think?’

‘Twenty or so … Maybe we could pull it off with fifteen.’

‘I’ve got the guys you saw. How many of you are there?’

‘Aside from me and Dandi, Satana and Scrocchiazeppi.’

‘Four and four makes eight. Less than half.’

‘You don’t think we can come up with the rest?’

‘Give me two weeks.’

Libano slumped back against the car seat, refreshed. Now, finally, this was starting to look like living.

III

KIDNAPPING THE BARON had been child’s play. Just as he’d expected. Libano reserved the right to wait until the kidnapping had taken place to announce the identity of the phone contact. There had been some grumbling, but Freddo had made his authority felt. The alliance was starting to hum. They were going to go far – very, very far. Together. As for the phone contact, Libano had an idea all of his own. Something that had a lot to do with loyalty, fear and domination over weaker vessels. As soon as he got home, he called Franco the barkeep and told him to send the punk around.

He showed up not half an hour later, his eyes still puffy with sleep. He was limping on his wounded leg, but at least he’d taken a shower, and he didn’t stink the way he did before. Libano invited him to take a seat in one of the armchairs draped in black fabric. The punk hesitated, his curiosity piqued by the bust on the side table, a purchase from the Porta Portese market.

‘Who’s that?’

‘Mussolini.’

‘Who’s he?’

‘A great man. Sit down.’

The punk did as he was told. A savage fear glittered in his eyes.

‘How’s your leg?’

‘So-so. I’m doing physiotherapy …’

‘Still shooting up?’

‘I’m clean, I swear.’

‘My arse. You want some work?’

‘What kind of work?’

‘You want it? Yes or no.’

The boy trembled from head to foot. Libano struggled to suppress a smile.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Lorenzo.

‘You look like a mouse, all hunched over and tight. A sorcio, a little scrabbly mouse, definitely … Well: yes or no?’

‘Yes.’

‘Correct answer. You just joined up, Sorcio. Now off you go to Florence, and until I say you can, no more needles. As for the job, I need you to make a few phone calls.’

Freddo got home at dawn, too. Gigio was waiting for him outside the front door, shivering with cold.

‘What are you doing out here?’

‘I’m not setting foot in that place again.’

‘Did Papa beat you up again?’

Gigio shook his head no.

‘So, what happened?’

‘I’ve had it! School’s a disaster, and I never have enough money. Why don’t you let me come work for you? I’m begging you …’

Gigio was six years younger than him. Polio had done a number on his leg, and his brain had never been anything to write home about either. Freddo felt a strange fondness for that unlucky younger brother of his. A different life, why not? There’s no law that says you can’t change your fate, is there? In one of his rare moments of fantasy, he’d dreamed of Gigio becoming a doctor. He reached into his pocket and handed the boy a hundred-thousand lire note.

‘Now go home, change clothes, and go to school. Or I swear I’ll break your nose and your jaw. Understood?’

Gigio hunched his shoulders and tucked his head in. He’d do as he was told, like always. And he’d stay out of all this mess, like always.

Once he was alone, Freddo flopped down onto the bed, without even taking off his boots.

IV

JUDICIAL REPORT ON THE KIDNAPPING FOR PURPOSES OF EXTORTION OF BARON VALDEMARO ROSELLINIby Commissario Nicola Scialoja

From the investigations conducted concerning the crime in question the following facts have emerged:

BARON ROSELLINI, at the time of the kidnapping, was driving his own vehicle, a camel-brown Mercedes turbo diesel. The kidnapping took place near La Storta, on the Via del Casale di San Nicola. The victim’s car was forced to brake to a halt at a sharp angle in the middle of the road by two other vehicles. According to the eyewitness account of Oscar Marussi, who was at the wheel of his own car, a FIAT 131, and was right behind the victim, the other cars were a CITROEN DS 21 and a light blue ALFETTA 1750. Marussi also reported that the two vehicles sped up next to the baron’s Mercedes, forcing it to a stop, whereupon four men got out of the ALFETTA, seized the baron, and dragged him over to the CITROEN, shoving him into the vehicle. The CITROEN took off immediately, heading towards Rome, while the remaining four criminals, after threatening Marussi, drove off as well, three of them aboard the ALFETTA, the fourth taking possession of the baron’s Mercedes. That car was found the following day on the Via Cristoforo Colombo, at number 459.

Telephone contacts with the victim’s family were made from areas outside the district (geographic regions other than Lazio) in order to thwart the tracing equipment installed by the SIP phone company.

All the same, from the tape recordings made by the personnel operating on the incoming equipment in the home of the victim, it emerged that the phone contact, always the same person, can be identified as a male, presumably no older than twenty-five to twenty-eight, and without any distinctive regional accent, or at least tending to simulate a variety of regional accents.

The family received five (5) written communications demanding a payment of ransom. They were composed in a technique involving a collage of various letters cut out of the most widely circulated Roman daily newspapers (Il Messaggero and Paese Sera and, on one occasion, Il Secolo d’Italia, an extreme right-wing publication).

The phone calls demanded an initial ransom of ten billion lire, then dropped to seven, and finally settled on three billion lire. According to statements by the family of Baron Rosellini, it would appear that this last sum was the amount actually paid.

The first message was left on 29 December 1977 near Piazza Cavour, and contained three Polaroid photographs depicting the victim of the kidnapping holding a copy of Il Messaggero.

On 2 January 1978, at 1600 hours, an appointment was made at the Bar Cubana, where the victim’s son, ALESSANDRO, waited in vain for a phone call that appears to have been made only after he left the premises. That same day, another appointment, at the Bar Georgia, was likewise unsuccessful.

On 11 February a message was reported to have been left by the kidnappers in a trash receptacle on the Lungotevere di Pietra Papa, but without results.

On 15 February, ALESSANDRO ROSELLINI was summoned to the Termini train station, to retrieve a message left in an automatic photo booth. The message, composed with the usual technique of letters cut from newspapers, ordered him to travel to Torvajanica. Upon arriving in this location, the young man found a second message, which set another meeting at the diner at the Pontecorvo service station on the Autostrada del Sole. No one came to that meeting, either.

The telephone contact criticized Rosellini, saying that he had been followed by three police teams.

On 23 February, another appointment was made at the restaurant Il Fungo at EUR, but again, no one showed up.

The same thing happened on 27 February in Piancastagnaio, near Siena.

On 2 March, on the Via Cassia, near the exit for Monterosi di Viterbo, the ransom was finally paid. The witness – who in that setting, by express order of the judicial authority with appropriate jurisdiction, was not being followed – reported that, on the orders of three individuals with their faces concealed who were seated in a parked FIAT van with a Viterbo (VT) registration plate, he had thrown out the bag containing the money.

The cash from the ransom was traced to various locations around Italy, but no successful investigative leads were developed as a result.

There is no need to point out that the failure of the hostage to return home, even after the full payment of the ransom, clearly indicates that this crime culminated in the most tragic of outcomes.

V

THE PROBLEM ORIGINATED with the Catanians from Casal del Marmo. What happened was the baron caught a glimpse of the face of one of his captors. He therefore had to be eliminated. Even if they’d had the chance – and they didn’t, they’d only been informed after it was all said and done – neither Libano nor Freddo would have lifted a finger to save the baron. For that matter, it was a lot less risky without live witnesses. But after giving Feccia – whose name roughly meant Filth – his share of the take, they decided to put an end to their dealings with those dilettantes. Bufalo, a young man from Acilia who was built like a refrigerator and had procured the chloroform and the Alfetta 1750, suggested wiping out the whole gang. But their giddy euphoria at successfully receiving the ransom won out: after paying those idiots from Casal del Marmo their share of the ransom, they still had two and a half billion to divvy up – according to the shares assigned during the planning phase. Two and a half billion to split ten ways.

Libano had summoned them all to the apartment at San Cosimato. Everyone was there. Along with Dandi, there was Botola, a short, thickset guy from the Piramide district, skilled with a pistol; Satana, something of a nut, but a good guy in a fight, with a light dusting of red hair on his head and dressed in a black jumpsuit that Diabolik would have been proud to wear; Scrocchiazeppi … In other words, the gang was all there, with the exception of Sorcio. Libano was suspending judgment on him for the moment: he’d clearly been high when he made a couple of the phone calls, and had come dangerously close to screwing up the whole operation. All things considered, though, he hadn’t done too badly. In any case, he’d pay for his screw-ups by forfeiting his share of the loot.

Right, the money. He had never seen that much money in one place, not even in a film. Still, the thing that he found most compelling was watching the reactions of the others. The Buffoni twins, for instance: Aldo – or Carlo, it was so hard to tell them apart – were trying to make themselves a hat with the notes. And Carlo – or Aldo – explained:

‘Fuck that arsehole of a father of mine, who wanted to send us to work for a boss.’

Bufalo had bought a vial of cocaine on credit, and he was sitting there in a stunned daze looking at the plunder, his nose all floury, every once in a while slipping into a sort of death-grin sigh (heh! hee! heh heh!). Dandi was leafing through a Ferragamo catalogue and a brochure from an art exhibition. Fierolocchio had pulled out of his pocket a crumpled piece of scrap paper covered with phone numbers.

‘The finest pussy in Rome!’

Beers and joints were being passed from hand to hand, and understandably everyone was thinking about the fastest, stupidest way to run through their share of the take from the kidnapping. Almost everyone. Freddo was standing off to one side. He was looking out the window: a grey dawn rising over the marketplace, a dense, chilly drizzle that penetrated into your bones.

‘Time to divvy the take?’ Libano suggested.

Bufalo had emerged from his drug-induced coma. ‘All right then: five hundred million lire went to the shitheads. So amen, we’re done with them. We have two and a half billion left over. That’s four hundred million apiece for Libano and Freddo. That’s a fair share; after all, they came up with the idea, right? That leaves one billion seven hundred. There’s eight of us, meaning two hundred million apiece. And the hundred million left over we can go shoot at the various floating card games. What do you say to that, huh?’

What need was there even to answer? They all threw themselves onto the plunder, even Scrocchiazeppi, skinny as he was – if you so much as bumped him with your shoulder there’d be nothing left of him. Only Libano and Freddo held back from the scrum: one of them with a hand resting on Il Duce’s oversized bald head and the other leaning against the window, a cigarette butt clamped between his teeth.

Libano decided to play his ace card.

‘Hold on, comrades!’

‘Now what the hell does he want?’ They all turned to stare at him, the way you would a lunatic wandering down the street. Bufalo even had his hand on the holster under his armpit. Suspicious, all of them smelling a trap. Libano sat there in his armchair, arms spread wide in a reassuring gesture. Freddo observed the situation with his usual intense focus.

‘Here’s what I’m thinking: now here we have two and a half billion lire. Which is quite a different matter from me having four hundred million, and you having two hundred, plus the hundred for the gambling dens …’

‘What the fuck are you talking about?’ Fierolocchio objected.

‘Shut up,’ Freddo broke in. ‘Go on, Libano.’

‘You, Dandi, I’ll start with you because we’ve been friends all our lives … Now, the first thing you’re going to do is update your wardrobe, because you’re Dandi, and if not, what kind of a Dandi would you be, right?’

‘To tell the truth, the Kawasaki’s looking a little beat up too …’

Scattered laughter. Bufalo’s hand fell away from the holster. Libano had a chance to catch his breath.

‘And you, Scrocchiazeppi … I dropped by Bandiera & Bedetti this morning: I’ve got my eye on a couple of Rolexes that’d make your eyes pop out of your head … Fierolocchio, for you … pussy, cocaine and champagne?’

‘Sure, it’s the finest life has to offer, right?’

More laughter. Libano was starting to get worked up. Even Bufalo was beginning to show a glimmer of interest.

‘What I’m trying to say is: we all have things we want, certain ambitions …’

‘We deserve what’s fair; we want what we’ve got coming to us!’ Satana raised his voice.

Heads nodded.

Libano stated his agreement. ‘What we’ve got coming to us is just one thing: the best there is.’

‘Then what are we waiting for? Let’s divvy the take!’

Satana would be the hardest one to win over, Libano could tell. For now, he spoke to him alone, staring into his small, delirious eyes.

‘So we split the take today. And tomorrow or the next day, before you know it, we’re back where we started. Cars get old, coke gets snorted, pussy dries out from a shortage of liquidity – and when I say liquidity, Fierolo, I mean cash. But what if we didn’t divvy up the two billion five? What if we kept it all united? What if we all stayed united? Do you have any idea what we could achieve? Instead of owning just a little, we could own more – a lot more. And the more we have, the more we can get … You remember the priest, Satana? To those who have much, much will be given … That’s what we ought to do: take less today so we can have everything tomorrow.’

‘Wait a second, let me get this straight …’ ventured Bufalo, definitely intrigued.

Libano smiled at him, but his eyes sought out Freddo. But who could say where Freddo was, lost in thought, standing there stiff, motionless, his eyes a pair of narrow slits.

‘Bufalo, here’s how I see it: let’s stay a team. We’ll take what little money we need for petty expenses … let’s say fifty million lire apiece …’

‘Same for you?’ Bufalo’s jaw dropped.

‘Same for me. Even split all around!’

‘All around, same for everyone?’ Satana asked, a mocking note in his voice, with a baffled glance in Freddo’s direction. Freddo was the other lion in the pride. It was up to him to issue a verdict. But Freddo didn’t move a muscle, his eyes roaming restlessly from the bust to the ugly framed mirror with the figurine of the Madonna under a glass bell, to the armchairs draped in black, to the stereo fenced in Via Sannio.

‘Fifty million lire times ten – that is, if we’re all in on this – means two billion lire left over,’ Scrocchiazeppi pointed out.

‘Two billion lire is a nice, solid foundation,’ Libano persisted. ‘We’re going to need guns and a safe place to keep them. Let’s say that we could invest a billion and a half, maybe a billion eight, for our little shared enterprise …’

‘So just what is this enterprise?’

‘You still don’t get it, Satana? I want the same thing the rest of you want!’

‘What’s that?’

‘Rome.’

‘Ba-boom! Mussolini has spoken! How the fuck do you think you’re going to take over Rome?’

‘By asking politely, and if that doesn’t work, we’ll just have to turn nasty, you stupid shit. We’ll use drugs. We’ll use gambling …’

Then all hell broke loose. Everyone wanted to have their say: words, threats, outlandish gestures. Libano got slowly to his feet and went over to stand next to Freddo. They exchanged an intense glance. A silence ran between them that isolated them from the rest of those present. Freddo extracted a revolver from his pocket and slammed it down hard on the side table.

‘Shut up for a second.’

He hadn’t even needed to raise his voice.

‘Libano has a point. If we split the money up, then it’s no good to anyone. If we split up, we’re no good to each other. Victory comes from unity. You’ve convinced me, Libano. An even split for everyone, and the rest goes into a general fund. Maybe we put something aside for urgent cases – say one of us winds up in jail, or has family problems …’

‘That’s only reasonable,’ said Libano. ‘When times are lean, we can finance our operation with this … let’s call it a strategic reserve. A couple of hundred thousand lire a month will come out of it anyway.’

‘I’m with you,’ said Dandi. The Kawasaki could wait; the historic heart of Rome, on the other hand…

‘Comrade, this is a great idea,’ snarled Bufalo, and went over and planted a resounding smack on Libano’s back. ‘Money, after all, is only good for one thing, and that’s to avoid problems. How can you compare it to the street?’

Fierolocchio said yes: he could still afford a couple of weeks of wall-to-wall sex, even if all he had was fifty million lire.

Scrocchiazeppi said yes: he’d find some other way of getting hold of the Rolex. The usual way.

Botola said yes: he lived alone with his mama and he’d promised her a washing machine, a dishwasher and a brand-new colour TV.

Aldo and Carlo said yes: Freddo’s word was law, as far as they were concerned.

When his turn came, Satana stopped to count the two hundred million lire, with a provocative manner.

‘I’m getting the impression you’re not on-board,’ Libano challenged him.

‘I’m getting the impression you’ve had a massive stroke.’

‘Hey, Satana,’ Dandi waded in, ‘it’s not our fault if the last strokes you remember involved the parish priest!’

Cruel laughter. And a vicious glare from Satana.

‘First: we’re talking about gambling. And everyone knows that Terribile controls the gambling around here …’

‘We’ll talk to him,’ Fierolocchio suggested, in a conciliatory tone of voice.

‘So what if he tells us to go fuck ourselves?’

‘We’ll shoot him.’ Bufalo liquidated the problem seraphically.

‘We’ll shoot Terribile? Exactly who here is going to shoot Terribile? You?’

‘Sure, I’ll shoot him. And if you don’t like it, I’ll shoot you too, you piece of shit!’

Bufalo was scowling. And Satana already had his hand in his pocket. Libano tried to calm the waters. The only thing missing now was a knife fight out in the street with the money out for all to see. ‘Hold on, hold on. So Satana’s not in on it? Fine, we’ll do it without him. Satana, you take your share and go where you like. We can still be friends.’

But Satana wouldn’t drop the subject.

‘Second,’ he resumed, ignoring the suggestion, ‘we’re talking about drugs. That’s the Neapolitans’ territory; they control that market. Now what are you going to do, Bufalo – shoot the Neapolitans, too?’

‘You’re wrong there, Satana,’ Dandi broke in. ‘Puma’s been importing shit from China for years and no one ever said a word to him …’

‘What are you wasting your time on this animal for?’ Bufalo muttered.

Satana didn’t hear him, or pretended he hadn’t heard him. Now he had it in for Dandi.

‘Puma kicks back a share to the Calabrians. Or didn’t you know that?’

‘We’re not going to kick back a penny to anyone,’ Libano said very clearly. ‘If anything, we can make deals between equals …’

‘Aw, you want to take over Rome, Libano, but no one’s ever going to take over this city. Anyway, what do you know about it? You’re half African …’

All eyes darted from Satana to Libano. Libano sighed. Would he and Freddo ever manage to get these boys’ feral nature under control? These people could flare up over nothing, and what you needed to get ahead in this world was a cold, clear mind. Satana was mocking him provocatively. If Libano failed to pay him back for his insult, he’d lose the respect of the others. He flashed a faint smile, shook his head, and let fly with a straight-armed slap that left a bright red mark on Satana’s cheek.

‘I’ll kill you, you bastard!’

There was bound to be a reaction, but Satana had been lightning fast, catching him off guard. Knocked off balance by a hip thrust worthy of the viper that he was, Libano found himself with a pistol jammed against his throat. Luckily, Freddo was on guard: a sharp knee to the kidneys and Satana sprawled out like an empty sack. Bufalo had grabbed the handgun, which slid out of Satana’s grasp as he fell.

‘Now let’s have a little fun with him!’

But Freddo grabbed the gun out of his hands and helped Satana back to his feet.

‘Now take your money and get lost, and just thank your lucky stars that we’re in such a good mood …’

Satana nodded, glowering. Before folding his tent and stealing away, he took a look around the entire panorama of the newly founded organization.

‘These two arseholes have set you up. You’ll figure it out, sooner or later!’

The minute he walked out the door, Bufalo took off after him. Libano stood in his way.

‘Where do you think you’re going?’

‘To deck that miserable turncoat, no?’

‘You’re not going to deck anybody at all, Bufalo.’ Freddo’s tone of voice made it clear that the point wasn’t open for discussion.

‘We’re an association now, comrade,’ Dandi explained. ‘We make all our decisions together and nobody’s an independent operator anymore.’

Bufalo nodded in agreement.

Alliances

February 1978

I

SATANA WASN’T WRONG. If you wanted to be a player in the narcotics market, you’d have to strike a deal of some kind with the Neapolitans. And that meant working with Mario the Sardinian. Bufalo arranged for the meet. When he felt like thinking, Bufalo was actually pretty sharp on things like that. The guarantor was Trentadenari, a guy from Forcella who was originally with the Giuliano gang. Then there’d been a quarrel with the Licciardiellos, allies of the Giulianos, and two ’Ndrangheta Santisti – made men – went down in a pool of blood. Trentadenari went to Cutolo for protection, and he was welcomed with open arms into the NCO – the Nuova Camorra Organizzata, or New Organized Camorra. Finally, in the aftermath of a peace talk between cumparielli, or Mafiosi, over pasta and fish – trenette con moscardini and pesce cappone all’acqua pazza – the mob tribunal had acquitted him, and now Trentadenari was considered by both factions to be a reliable intermediary. Not bad for a guy who had defected not once but twice, winning a reputation as well as the moniker of a Judas – in fact, Trentadenari meant ‘thirty pieces of silver’.

Trentadenari had attended the Genovesi high school, and he came from a respectable family. He boasted a formidable network of contacts and fine manners. He was a big hulk of a beast, stood six foot two, and was arabesqued from head to foot with tattoos that – he claimed – went perfectly with the flashy Marinella neckties that he loved to wear even at home, in the nude. With the money he made dealing cocaine, he’d had his oversized apartment decorated in the latest Paolo Portoghesi style. The place was in the EUR district, near the homes of certain Roman nobility.

‘The princess is a real lady,’ he liked to say, as he showed his guests the veranda overlooking a courtyard filled with towering magnolias and classical Italian garden hedges. ‘Too bad she’s a Communist. I have to say I can’t figure out these rich folk that trend Red!’

Libano had to agree. He was a long-time Fascist; the way he saw it, right wing meant order and organization. Which is what he was trying to do with the gang – impose order and organization on a band of undisciplined hotheads. Power must reward those who see clearly and have the strength to impose their vision.

While Bufalo and Trentadenari exchanged hugs and a series of jovial insults, Freddo and Libano inspected the place. It all seemed safe and secure enough. Dandi, on the other hand, was knocked out by the sheer magnificence of Casa Trentadenari. Designer furniture, little round glass tables, a stereo system with ultramodern speakers, a cinema-quality screen, an immense living room with sprawling sofas … Now that’s what you call style! That’s definitely what you call living … Trentadenari locked arms with him, all friendly.

‘So you like it, eh? If I tell you how much the architect bled me for all this … But you see the professional touch, right? Let me put on a little music.’

Gloomy droning church music poured out of the enormous speakers. Bufalo put his hands over his ears. Libano asked, wryly, whether the architect had picked the records too. Trentadenari explained with a laugh that it was ‘mood music’ that he used to seduce lady psychologists, lady journalists, and even a lady lawyer or two.

‘Even lady lawyers?’

‘They’re the biggest sluts of them all!’

Mario the Sardinian kept them waiting until sunset, when they were all starting to get sick of the music and Trentadenari’s over-abundant hail-fellow-well-met routine. He’d brought Ricotta with him. Libano was astonished to see an old fellow gangster he’d long since given up for buried, if not underground, after years of jail time.

‘I had a good lawyer. He pleaded me down to concurrent sentences and now here I stand!’

Mario the Sardinian, known as Sardo, had escaped from the criminal insane asylum of Aversa two months earlier, while out on probationary leave. Accused of attempted murder, extortion and armed robbery, a psychiatric evaluation had allowed him to pull off a finding of mental infirmity. And he’d earned it, no question about that: at his first session, he’d pissed on the psychiatrist’s papers; at the second session, the doctor had shown up with four guards and Mario had remained closed in a wall of silence; during their third meeting, he broke down sobbing like a little boy, demanding a pacifier and a baby bottle. The tests and evaluations dragged out for over a year, amid general dismay. In the end, Mario had won the trust of the prison chaplain and, in a bid to overcome the psychiatrist’s flagging objections, he’d staged a fake suicide attempt, in which he supposedly tried to suffocate himself with an overdose of consecrated communion wafers. When all was said and done, he’d been declared clinically insane, something of a menace to society, but only just, keep that in mind, eh! His escape – theoretically a mistake, since it was only three months until his next psychiatric exam – had been in compliance with a specific order issued by Cutolo. Sardo and Professor Cervellone had met, in fact, at the Aversa asylum, and Sardo had kept after him with such persistence that in the end Cutolo decided to go ahead and baptize and bless him, appointing him the underboss of Rome. In a sense, Libano and his men had played a role in Cutolo’s decision to send his new lieutenant to the territory of Rome: ‘prison radio’, as the prison grapevine was known, was reporting that the Rosellini kidnapping was the handiwork of Cutolo’s Neapolitans, and the Camorra boss had ordered an investigation into those claims.

‘And instead it turns out it was you guys!’

‘And instead it turns out it was us.’

‘It went pretty well, considering it was your first job,’ Sardo conceded.

He was almost completely bald, short, squat, his forehead grooved with an ancient knife scar. When he said jump, Ricotta leapt straight into the air, and even Trentadenari treated him with considerable deference. Libano disliked him immediately. Impossible to say what the inscrutable Freddo thought of him.

‘We’ve got some money to invest and we’d like to put it into a shipment of shit,’ Dandi explained.

‘How much money?’ Sardo asked flatly.

‘One, one and a half …’

‘We can make that happen. Trentadenari has established a good network with the South Americans. I’ll procure the coke for you and I’ll authorize you to put it on the market, as long as you stay out of Terribile’s territory. I get seventy-five per cent of your profit and ten per cent of the overall capital investment.’

That’s worse than the deal you’d get borrowing money from Cravattaro in Campo de’ Fiori, Dandi decided instinctively. Libano stroked his chin. Freddo sat there, his eyes half-lidded. Bufalo seemed to be making an effort to follow the conversation, leaning forward to grasp the transitions that escaped him. Trentadenari, feigning indifference, was rolling a spliff. Ricotta knotted and unknotted a garish tie, decorated with a yellow sun and a black moon.

‘Maybe Dandi failed to make himself clear,’ Libano said, unruffled. ‘We’re not asking for anyone’s authorization, and we couldn’t give less of a shit about Terribile. We’re offering you a business deal. A fifty-fifty cut, from start to finish. You sell us the shit at the price that we set and we split the profit. For all of Rome …’

The Sardinian got a nasty look on his face.

‘Do you understand who you’re talking to, Libano?’

‘If we didn’t, we wouldn’t be here,’ said Freddo drily.

The Sardinian stared at him with a look of astonishment. There was something imposing about Freddo, Libano decided.

‘Let’s say that we did this deal. If you want to cover all of Rome, you need a hell of a lot of people. How many men do you have?’

‘Fifteen or so,’ Dandi ventured.

‘That won’t be enough.’

‘We can find more men, no problem,’ Dandi insisted.

‘They still won’t be enough.’

‘You could get in on it yourself,’ Freddo suggested. ‘With some of your own men, I mean …’

‘A joint operation, in other words.’

‘I think I said that, no?’

Sardo turned to Libano.

‘How do you plan to proceed?’

‘By organizing the network into zones. Each zone includes two or three quarters. Each quarter has six or seven ants and a horse overseeing them. The ants report to the horses and the horses report to us. Considering it all, we’d have, maybe, eight zones …’

‘What about the competition?’

‘We can work out an understanding with Puma. We’ve known each other all our lives. Everyone else is just small fry …’

‘And Terribile?’

‘If he’s open to it, fine. Otherwise …’ Libano let his voice trail off at the end of the phrase, but it was hard to miss his meaning.

Sardo scratched his scar. ‘You’re asking a lot. Nothing like this has ever been done before in Rome …’

‘So much the better. That means we’ll be the first. You and us. Together.’

Freddo again. Decisive; cold, hard steel. A boss.

‘Together? Maybe. But just one boss. Me,’ said Sardo.

‘I’m hungry,’ Dandi ventured.

A long silence followed. Bufalo and Trentadenari exchanged a glance and headed for the door. Ricotta followed them.

Out in the street, signs of winter: girls in maxi skirts and a dark, ominous sky, with rumblings of thunder. Bufalo and Trentadenari dragged Ricotta into a nearby rosticceria, where they ordered roast chicken, potatoes and pizza for everyone.

‘You think this’ll work out?’ Trentadenari asked.

Bufalo spread his arms in an agnostic shrug. And added that Sardo was a real arsehole.

‘No, don’t say that, Mario’s just that way. You’ll see, in the end it’ll work out …’

‘A greedy arsehole,’ Bufalo confirmed.

On the way back, Ricotta informed them that the Court of Cassation had ordered the burning of Pasolini’s last film. They couldn’t have cared less about the fact, but they let him talk because he was a friend. When Ricotta was a kid, he’d put in a few cameo appearances, in Rome’s Faggotville, Borgata Finocchio. The word was that Pasolini in person had taught him to read and write. He’d never become an intellectual, but as soon as he got out of prison, he’d gone on a pilgrimage to the Idroscalo, where that nutcase Pino la Rana had murdered the queer poet.

They got back just in time for the round of hugs goodbye. Dandi informed them of the terms they’d struck: 50 per cent for everyone, and an extra five in cash to Sardo for ‘staking his name and guaranteeing the good outcome of the deal’. They’d handle the cash receipts fifty-fifty, Trentadenari and Dandi, which is to say, one from each gang. As for who would be boss, they’d come to a compromise: they’d all ask Puma to take on the role of guarantor, a non-partisan arbiter. Obviously, Sardo was convinced he was the top dog, no matter what anyone said. The first shipment of coke would come in fifteen days from then, via Buenos Aires. So it was a done deal.

As he watched the way Libano, Freddo and Dandi exchanged glances behind Sardo’s back, it became clear to Bufalo that it wouldn’t last long.

‘Take it from me,’ he whispered to Ricotta, ‘forget about that guy. You’re one of us.’

II

PUMA HAD COME into the world forty-two years ago, and half of that time on earth he’d spent variously in the Albergo Roma and the Regina.* For the past few years he’d been living with a Colombian girl twenty years younger than him, a mestiza with an Indio nose, the niece of a gangland soldier in the ranks of the Calì cartel. The couple lived with their newborn son, Rodomiro, in a small villa on the Via Cassia.

Four of them went to the meeting: Dandi and Freddo representing one side, Trentadenari and Ricotta on the other. Puma was waiting for them in the yard, with his baby in his arms and a large German shepherd that sniffed at them uneasily, wagging his long thick tail. The Colombian girl served alcohol and fruit tart. Trentadenari, in his usual colourful language, set forth the terms of the proposed deal. Puma let him talk without blinking an eye. And in the end, with all eyes trained on him, he said no.

‘Hey, Puma, what are you talking about? We’re practically handing you the gold medal!’ Ricotta blurted out.

The dog snarled. The baby started whining. The Colombian girl appeared inside the house, looking out a window. Puma handed the baby to her and lit the stub of a Tuscan cigar.

‘I’m retiring, Ricotta. Tell Libano and Sardo, tell everyone you know, especially the cops …’

Everyone laughed. Puma took two deep drags on his cigar.

‘I’m tired. I already have everything I need: this house, a little money in the bank … Maria Dolores … the baby boy … did you see how handsome he is? No, I’m tired. I’ve had enough of this life …’

‘You’re talking bullshit, Puma. In just four days, I know you’re taking delivery of a kilo from the Chinaman via Palermo. Everyone in Rome knows about it.’

Puma turned slowly to look at Freddo.

‘If you let me keep that kilo, you’d be doing me a favour. I’d be in your debt. If you want to take it, go right ahead. This is my last shipment. It’s up to you. I’m going to kick the dust off my shoes. That’s right, I’m getting out of Rome entirely …’

His unruffled calm had made quite an impression on Freddo. Puma never talked just to hear the sound of his voice. If he said he was getting out, it meant he really was getting out. Was it a matter of age? Was he really as worn out as he was trying to make them believe? Freddo couldn’t seem to make all the parts add up.

‘Plus, you guys know, I’ve been in the underworld for twenty-five years now. I’ve seen it all and I’ve done it all. What do guys say these days? I’ve got a very presentable résumé. But there’s two things I just can’t stomach: kidnapping and murder. I’ve never nabbed anybody, and I’ve never killed anybody either …’

‘We were as sorry about what happened to the baron as anybody,’ Dandi ventured, ‘but what were we supposed to do about it?’

‘That’s not what I’m talking about, boys. The past isn’t what worries me …’

‘Then what’s worrying you?’ Freddo asked.

‘The future. What’s about to happen to every one of us … That’s why I’m stepping aside, Freddo …’

‘Why, what’s about to happen, in your opinion?’

Ricotta was all puffed up: chest thrust forward and the usual ridiculous tie fluttering in the breeze. Trentadenari, who had indulged in a nice little cashmere jumper from Cenci for the occasion, gazed at him with a look of commiseration.

‘What’s going to happen is you’re all going to tear each other limb from limb like a group of pigs. You’re going to finish each other off like so many dogs. I guarantee it. And I don’t want to be there when it happens.’

‘Come on, boys,’ Trentadenari exploded. ‘Now the old man’s casting the evil eye!’