Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

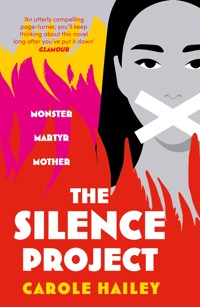

The gripping story of what it's like to be the daughter of a woman who changed the world - perfect for fans of The Handmaid's Tale and The Power A BBC RADIO 2 BOOK CLUB PICK AND KINDLE NO. 1 BESTSELLER 'Engrossing and original. The Silence Project will get people talking' Bernardine Evaristo Mother. Martyr. Murderer. On Emilia Morris's thirteenth birthday, her mother Rachel moves into a tent at the bottom of their garden. From that day on, she never says another word. Inspired by Rachel's example, other women join her and together they build the Community. Eight years later, Rachel and thousands of her followers shock the world as they silence themselves forever. In the aftermath of what comes to be known as the Event, the Community's global influence quickly grows. As a result, the whole world has an opinion about Rachel - whether they see her as a callous monster or a heroic martyr - but Emilia has never voiced hers publicly. Until now. Readers can't stop shouting about The Silence Project: 'A true masterpiece' ***** 'One hell of a book!' ***** 'Had me hooked' ***** 'Red-hot' ***** 'I don't think I've ever read a book as quickly' ***** 'Gave me the shivers' *****

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 531

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2023 by Corvus,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Carole Hailey, 2023

The moral right of Carole Hailey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 606 6

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 617 2

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 607 3

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Mum and for Pete, with love

Preface to the first edition ofThe Silence Project: The Life and Legacy of Rachel Morris

by Emilia Morris

In a fire, you die long before your bones ignite. Skin burns at 40°C. Above 760°C, skin turns to ash. Bones are less flammable because they need to be exposed to 1200°C to burn, although long before that the layer of fat which you carry under your skin will boil. Your internal organs will explode. You will be dead even though your skeleton remains intact.

On 31 October 2011 I watched my mother burn to death. It wasn’t an accident. She built her own pyre. She doused it in petrol. She climbed up and stood with her legs apart, bracing herself. I didn’t know what she was planning. I assumed it was another publicity stunt, which of course it was, just not in the way that I was expecting.

Mum was wearing a green dress with diagonally cut pockets. From one of them she produced a lighter and briefly held it above her head as if it was a trophy. Even then, I was convinced she would walk away. I’m sure the press thought so, too. In those later years, Rachel of Chalkham’s protests always attracted television crews, but nobody could have anticipated that they were about to witness the scoop of their careers.

I am surprised by the details I remember from that day. I can feel the pressure of Tom’s arm around my shoulders as we watched my mother. I remember the smell of his fingers as he stroked my cheek. I remember the sky was cloudless, which was unusual for an October day in Hampshire. I remember my mother didn’t look at me. Not once. Not as she crouched down, wobbling slightly. Not as she ran her thumb along the top of the lighter, cupping her left hand around it. Not even as she lowered the flame towards the petrol-soaked branches.

What I remember most clearly about that day is that my mother died as she had lived: in complete silence. The pain of melting skin and boiling fat must have been excruciating in the seconds before her nerves stopped carrying signals to her brain, yet my mother did not cry out. Rachel of Chalkham. Silent to the end.

It has been eleven years since my mother’s death, but the questions never stop. Everyone remains just as fascinated by her as they have always been and believes this gives them the right to ask me anything. What was Rachel of Chalkham like when she was plain Rachel Morris? How do I feel having the architect of the Event as my mother? Am I proud of her? Ashamed of her? Do I feel any guilt about what she did? Question after question, year after year, until I have had to accept that the questions aren’t going away. On the contrary, my silence seems to fuel their obsession (just like her silence fuelled everything that happened).

Rachel’s story has been told multiple times; at least that is what the authors of all the biographies on my desk would have you believe. They are unofficial because I have never let anyone have access to my mother’s notebooks, and my father and I have never given interviews, except in those terrible hours immediately after the Event. Every so-called biography of Rachel is cobbled together from the internet and all of them contain information ranging from the downright false to the wildest conspiracy theories.

For years, I did my best to ignore the existence of the notebooks. They were in a box which was first stored in an attic, then beneath the stairs, then under a bed. I didn’t want to read them, and I didn’t want anyone else to read them either. Sometimes, I would even hope that I might be burgled and the box stolen. Wasn’t there already enough obsession with my mother without publishing her notebooks? But I’ve come to realise that the demand will not go away. The Community has made sure of that.

It has been widely reported that my father disagrees with my decision to allow publication of my mother’s notebooks and I want to take this opportunity to state that this is not correct. The decision was a difficult one, and we both have mixed feelings about it. My father is apprehensive about the consequences of making my mother’s words public; however, on balance, we both believe that publication is essential in light of what the Community has become.

The day Rachel stopped speaking she turned away from our family and towards the publicity that she and her Community courted. The Community may be my mother’s legacy, but the twenty-nine notebooks chart her life between 24 May 2003 when she left our home and 31 October 2011 when she lit those branches and changed the world for ever. The notebooks are legally mine, but in every other way I accept that they belong to everyone. They belong to all those people whose lives have been shaped by what Rachel did and all the actions taken in her name since her death.

Countless people who never met her claim to understand who Rachel was. She was a demon. A heroine. The most important person to have lived. A saint. A devil.

Rachel was none of these. She was neither saint nor demon. No matter what she did, Rachel was very human. She was deeply flawed and deeply courageous. She was a bad person and a good one. She was also my mother.

This is my account of the life and legacy of Rachel Morris. It is intended to be a companion piece to her notebooks. An explanation, in so far as I am able to provide one, of what it was like to be the daughter of the woman who changed the world. It is an attempt to explain why Rachel did what she did, how she convinced all those other women to do what they did and how their collective actions changed the course of history. Scientists and political commentators believe my mother’s actions averted catastrophes on a global scale, but in doing so, she set in motion countless other tragedies, many of which are still taking place as I write. The Community today is a malignant and rapacious organisation, entirely unrecognisable from my mother’s original silence project.

In endeavouring to provide a truthful version of Rachel’s story, I have written very little about events that I wasn’t personally present at, such as what she did in the years I was at university. For people who wish to cross-refer, I have included page references where I’ve quoted from the notebooks. To add context, I’ve used various contemporaneous reports and I am indebted for the permissions I was given to reproduce the many articles to which I refer.

I asked several people to provide accounts of their recollections; some agreed, others didn’t. I am extremely grateful to those individuals who were brave enough to revisit often distressing memories.

Most of all, I have to thank my father. Being the man who was married to Rachel of Chalkham is an invidious cross to bear, and although Dad remains deeply uncertain about this whole enterprise, his support and love for me is steadfast.

Finally, it is with the greatest of respect that I ask when you’ve read what I have to say about my mother, please draw your own conclusions, then grant me the freedom to step away from the suffocating shadow cast by Rachel of Chalkham.

Emilia Morris

Editor’s Note

As mentioned in the author’s preface, this book contains extracts from Rachel Morris’s twenty-nine notebooks (published by Rampage Press). The location of each extract in the notebooks is identified using the referencing style: (# of notebook, page number(s)).

Below are brief descriptions of each of the twenty-nine notebooks. The notebooks themselves have been donated by the author to the British Library.

#1 Mega Jotpad, A4, flexible laminated covers, wirebound, lined, approx. one-third of back cover missing

#2 Moleskine, navy blue, A4, softcover, lined

#3 Oxford Black n’ Red, A4, hardcover, casebound, lined

#4 Oxford Black n’ Red, A4, hardcover, wirebound, unlined

#5 Pukka Jotta notepad, A4, wirebound, front cover torn

#6 Moleskine, navy, 19cm x 25cm, softcover, lined

#7 Moleskine, pale blue, large, softcover, lined

#8 Unbranded, yellow flowers on grey background, A4, wirebound, softcover, lined

#9 Tivoli, dark brown, recycled leather, A4, softcover, lined

#10 CIAK, dark green, A4, softcover, lined

#11 Paperblanks, floral design, 23cm x 18cm, hardcover, ruled

#12 Ryman, orange, 29.5cm x 21.5cm, softcover, ruled

#13 Moleskine, black, large, hardcover, ruled

#14 LEUCHTTURM1917, red, A4, hardcover, ruled

#15 CIAK, light grey, A4, softcover, lined

#16 Smythson, mustard, A5, leather-bound, lined

#17 Moleskine, lime green, A4, softcover, unlined

#18 Moleskine, black, A4, hardcover, lined

#19 Aspinal of London, neon orange, A4, calf leather, ruled, pp. 45–66 missing

#20 Moleskine, black, large, hardcover, ruled

#21 Moleskine, black, large, hardcover, ruled

#22 LEUCHTTURM1917, red, A4, hardcover, ruled

#23 Rhodia, black, A4, softcover, wirebound, ruled

#24 CIAK, red, A4, softcover, lined

#25 Oxford Black n’ Red, A4, hardcover, casebound, lined

#26 Moleskine, red, 19cm x 25cm, softcover, lined

#27 Unbranded, hand-tooled, green leather, R.M. picked out on front cover in gold leaf

#28 Montblanc, black, A4, full-grain cowhide covers, lined

#29 Pukka Jotta notepad, green, A4, wirebound, ruled, front cover torn, rear cover missing

Before the Event

24 May 2003–31 October 2011

1.

On Saturday 24 May 2003 – the day of my thirteenth birthday and 3,082 days before the Event – my mother left home.

She didn’t go far. After dragging assorted metal poles and canvas paraphernalia past the people enjoying drinks in our beer garden, she managed, with a considerable amount of effort, to pitch a tent beside the stream that marked the boundary between our bottom field and a small wood. At first, I believed the most important thing was to find out where my mother had got the tent, because we had never owned such a thing. However, it wasn’t long before I realised that the tent (which had been abandoned in our garage by some campers the previous summer) was the least significant part of the story.

I really wanted to have my thirteenth-birthday party at Hollywood Bowl in Basingstoke, but we couldn’t afford it. Instead, my parents had agreed that to mark my entry into touchyteensville, as Dad insisted on calling it, our pub would stay shut until 2 p.m. My party would begin at 11 a.m., so my friends and I would have the run of the place for three whole hours. For me, the pub wasn’t an exciting place to spend my thirteenth birthday. I was as much of a fixture as the 1998 Beer of the Year calendar, which had been hanging above a shelf of glasses for almost five years. It was perpetually turned to November’s offering, which I can still remember word for word: a hoppy delight replete with a sensational fruity palate and an unexpectedly noble head. Clearly the brewery marketing department had employed an aspiring poet in love with the adjective.

Although I would rather have been somewhere else, my friends had worked themselves up into a frenzy at the idea of a party in a pub.

‘JD and Coke, Nick, and hold the ice,’ Sarah Philips yelled at Dad as she ran into the pub on the dot of eleven. She was so excited that I wouldn’t have been at all surprised to find out she had spent the night sleeping outside. She shouted the same thing several times more, pushing her chest forwards and her bum backwards to such an extent that she looked deformed. At some point in the last twelve months, flirting had become one of our most popular hobbies, but Sarah hadn’t even been in the pub for five minutes and she was already crossing a line. Fortunately, Dad was completely oblivious to Sarah’s contortions, even though, as Gran was fond of saying, Sarah Philips was thirteen-going-on-thirty.

‘What about brandy?’ suggested Bea Stevens. ‘Mum always lets me have brandy when I’m upset about something. She says letting me drink a little bit now means I won’t be an alcoholic when I’m older.’

Bea’s mother might have had a point, but nowadays I cannot bear the stuff. Ever since that police officer put some in my tea on 31 October 2011, just the smell of brandy is enough to make me gag. I did wonder afterwards if she had taken one of the bottles from the bar downstairs or whether all police officers carry a hip flask around with them, just in case. She made us sit at the kitchen table while she busied herself with the kettle, murmuring, ‘It’ll take the edge off,’ as she poured a great big slug of brandy into each cup of tea. She meant well, but it didn’t help. Nothing could. And it tasted revolting.

My father stood firm on the subject of alcohol at my party – we were only thirteen, after all – but, being Dad, he did his absolute best to make sure we enjoyed ourselves. He piled fifty-pence pieces on the ledge by the jukebox, and although the machine was full of all the old music that he liked, that didn’t stop us queuing up to pick songs, self-consciously shuffling our feet while doing bad lip-synching to bands called Human League, Culture Club, ABC and Howard Jones (who Mum always used to joke was Dad’s twin, because they had the same long face and floppy hair). There were no boys present. They were the main topic of conversation, obviously, but there was no way I would have invited an actual boy to my birthday party because I would have literally died of embarrassment.

Dad had given in to my endless pleas to let us use the pool table, although he said the darts were strictly out of bounds. ‘It’s bad enough in here on match nights with darts flying around all over the place. Sorry, Ems, but no way am I going to let your lot loose on them.’

He always grumbled about darts evenings, but I knew he didn’t mean it because of how often he said we relied on the money from match nights. Apparently it was good for our bank balance when the Boar’s Blades won, because the better they did, the more they would drink. The team was named after our pub, which was called The Wild Boar, which was itself named after the huge white boar carved into a hill just outside Chalkham, which, as everyone knows, is where we lived.

So, no darts on my birthday, but the pool table was a great hit, despite everyone initially pretending they had no interest in playing. By the time Dad had wiped clean the blackboard and written down our names, our excitement, fuelled by the limitless supply of fizzy drinks and crisps in five different flavours, had reached fever pitch. Dad rode the wave of our enthusiasm, holding a rolled-up magazine against his chin like a microphone and commentating as if we were at the Embassy world snooker championships.

‘And as we watch newcomer to the game Olivia Taylor lining up on the stripes,’ he half-whispered, rasping his voice as if he had a fifty-a-day habit, ‘all her opponent can do is hope she misses… But Olivia strikes it well…’

Olivia – Livy – who by then had already been my best friend for eight years, really did not strike it well – she was far more interested in making sure that her hair fell the right way, so it would look just as good to everyone standing behind her as it did to those standing in front – but that was my dad all over, always the peacemaker, the pacifier. My wonderful father. The consummate pub landlord.

Once the tournament was finished – I have absolutely no memory of who won – we again congregated in front of the jukebox until my mother made an appearance, carrying a large chocolate-caramel cake that Gran had spent all of the previous day making. My face burned with pleasure and embarrassment as everyone sang happy birthday. Afterwards, we ate slabs of cake, then everyone was given a bag of their favourite crisps to take home, the pub door was unlocked, punters started arriving and my party was over.

If I look over the top of the sofa from where I’m sitting at the table I’ve commandeered as my writing desk, through the window of the flat, and wait for a gap in the passing traffic, I can see the building on the opposite side of the street. Although it’s an old pub in the middle of London and completely different to The Wild Boar, the sight of the sign hanging outside takes me back to my childhood: the beer wheezing out of the pumps and into the glasses with a splurt, the ever-present cigarette smoke (my nickname at school was Ashtray), Dad’s terrible music, Mum ringing the bell for last orders and calling time.

It is tempting to write about my life before I turned thirteen, but this is a book about my mother, the choices she made and the consequences of those choices, so I have decided to begin with the day of my thirteenth birthday because, as far as I am concerned, that’s when everything changed. Before then, my mother had just been Mum; it had simply never crossed my mind that one day Mum would become somebody else.

At first, I thought my mother had planned the whole tent-by-the-stream thing as a sort of birthday treat, that we would camp out together under the stars, which would have been entirely in character for her. When people ask me what she was like before she left, before her silence, before the Community, they almost always begin by asking what she was like as a mother. ‘Tell me about her parenting style,’ they say and I know they are expecting me to reply, ‘Well, it was all there to see in my first thirteen years, if only I’d known what I was looking for,’ or, ‘Looking back now, it’s obvious what she was planning.’ But that’s bullshit. I mean, she was my mother and it’s not like I had another one to compare her to. Honestly, the only thing I can really say about Mum’s parenting style was that occasionally it was a bit wearing trying to anticipate which mother would make an appearance on any given day.

For example, sometimes on weekends she would come into my room, snuggle under my duvet and gossip about my friends. Other times, she’d be all bossy and nitpicking, demanding to see my homework, going through it line by line, questioning and criticising, although the rest of the time she displayed little interest in my education. Occasionally, confessional mother would appear, and she would tell me things I really didn’t want to know, like the time, when I was about ten, when she decided to confide in me in detail, and I mean graphic detail, about how, when and where she lost her virginity.

The incarnation I most disliked was counsellor-mother. Mum would sit herself down opposite me and demand that I tell her my worries. Back then, my anxieties usually revolved around my appearance, or which boys hadn’t talked to me, or which boys had talked to me, and what they’d said. I didn’t want to tell Mum those things, though, because when she did finally force me to confess them, she would laugh at me and say, ‘Lucky you, Emilia, if that’s all you’ve got to worry about.’ What, I always wondered, was the point of asking if she was only going to dismiss whatever I said? Come to think of it, since she subsequently dismissed everything I had to say about what she chose to do, maybe the signs were there after all.

One thing I definitely remember from the afternoon of my thirteenth birthday is staring out of the bathroom window in the direction of the stream, watching Mum jabbing poles in the vicinity of various flaps as she struggled to put up the tent. I assumed that this flurry of activity was a result of yet another maternal incarnation. Perhaps she was planning to try being an earth-mother. ‘Look at the stream, Emilia, imagine your negative feelings drifting with the current.’ That sort of thing.

Midge was with her, nosing around, and one side of the tent had just collapsed on top of him, leaving only his front paws sticking out, when Dad yelled up the stairs. ‘Rachel, I could do with some help down here.’

After a few seconds he shouted again. ‘Ems, where’s Mum?’

‘Putting up a tent,’ I shouted back.

‘What?’ he yelled, although I don’t know why he bothered. Once the pub filled up, it was impossible for anyone downstairs to hear what anyone upstairs was saying. But that didn’t stop Dad bellowing up the stairs several times a day, then waiting in vain to hear a response.

It is no exaggeration to say that the noise of the pub was the soundtrack of my childhood. Three rooms, all in a line: the bar, the snug and what we called the games room, because that was where the pool table and darts board were. There were doorways, but no doors, so you could stand by the fireplace in the snug at one end and see all the way through to the dartboard in the games room at the opposite end. My bedroom was above the games room, which was usually the quietest part of the pub because Dad never put any heating on in there, except on match nights. I lost count of the number of times the Blades asked him to turn it on for their Monday-evening training sessions, but somehow or other he always managed to forget. That’s what he said anyway. In winter, the darts players would bring extra layers of clothing with them to put on once they got to the pub.

I liked Mondays best. Generally, no one got too drunk and I would go to sleep to the thwunk of darts hitting the board without any of the shouting that jolted me out of my sleep on other nights. As the week went on, the volume of the punters increased. So too the volume of the jukebox. It was an unwinnable competition: the louder people spoke, the more Dad turned up the music; the louder the music, the louder people shouted.

‘Silence is bad,’ Dad would say. ‘Silence means no punters. And you know what that means…?’ I knew all right. No punters, no money.

Sometimes, I try and convince myself that this is why I hate silence. That maybe this is why silence makes my heart thump a bit faster, my mouth go dry and my palms sweat. Perhaps this is why the sound of silence makes my brain fill with thoughts of burnings, drownings, plane crashes, cancer and shootings. The lack of noise lets in thoughts about whether today is the day that I’m going to have a head-on collision in my car or choke on my dinner and asphyxiate or fall, hit my head on the side of a table and die from a subdural haematoma. Silence makes me wonder if this is my last day or hour or minute on earth. I have lived through the worst thing and I’m still here, but that doesn’t stop the sound of silence terrifying me. It makes me want to scream, but I don’t because what if I open my mouth and nothing comes out?

There was no silence on my thirteenth birthday. The pub filled up quickly after my party – it was hot, the windows were wide open all day long, and sunshine always made people want to come and drink – so by the time Dad called up the stairs to ask where Mum was, it was already really busy. I went back to the bathroom window to check how she was getting on with the tent. She was turning one of the metal poles end over end, as if she was hoping it might spring from her hands and plant itself wherever it was supposed to be. Midge had extracted himself from the canvas, and each time the end of a pole swung past him, he would lunge towards it, snapping his jaws. I looked at myself in the mirror over the sink, examining my face. Back then, I checked for spots at least once an hour. Mum had helped me straighten my hair for the party, and if she wanted me to sleep in the tent with her I would have to find something to tie it up with or else it would be frizzy by the morning.

I went down the stairs, walked five steps along the hallway and then, with the sixth step, I left our home and was in the pub. I stood at the end of the bar, listening to the buzz of voices fuelled by the first drinks of the day. Eventually, Dad caught sight of me and beamed. ‘Collect the empties for me, love,’ he said, pouring a beer. ‘But before that, give Mum a call, will you? It’s manic in here.’

‘She’s down by the stream,’ I said.

‘What’s that?’ He frowned at me, puzzled.

‘Mum. She’s down by the stream.’

‘What the f—?’ He stopped himself. ‘What on earth is she doing? Go and get her would you, Ems?’

‘Mum first, or the empties?’

He looked at the shelf of glasses. There were still a few clean ones. ‘Mum first. Thanks, Ems…’

The beer garden was warm as I picked my way through the glasses abandoned on the grass; I’d collect them on my way back. Mum was still concentrating on trying to put up the tent and she didn’t notice me approaching, so when I said her name she swung around and almost brained me with a metal pole.

‘Dad says he needs you behind the bar.’

She put the pole on the ground. Then she put her hands on her hips and looked at me. Midge nudged my leg with his head and I tugged his ear.

‘Come on, Mum. Dad needs you – it’s really busy inside.’

She shook her head really, really slowly, like she was worried it might fall off.

‘What are you doing, Mum?’

She pulled a pen out of her pocket and a notebook, which I was annoyed to see she had pinched from my room. I had an extensive collection of notebooks, although I rarely used more than a page or two of each one, scrawling down a few angst-riven musings about the tribulations of my life, which I’d invariably forget about the next day. Staying here, she wrote in my notebook. Need peace and quiet.

It is worth noting that this notebook – which, as far as I can recall, was a purple Paperblanks notebook that Mum herself had bought me – should technically be notebook #1, but it was not among her belongings when the police eventually returned them to us several weeks after the Event. I have no idea what happened to it. Perhaps my mother decided there was nothing of any relevance in it and chucked it out, maybe one of the Members took it – who knows? In those very early days, my mother made no attempt to separate what she wrote down for herself from the notes she wrote for Dad and me, and in what is the official notebook #1, you can clearly see messages she wrote for us, mainly mundane requests for things she wanted brought from the house. For example: ‘E. pls bring 2 T-shirts and navy jumper that Gran bought me’ scrawled in a margin (#1, p. 13). You can also see my mother’s point-blank refusals to even consider leaving the tent and moving back into our home. ‘No!!! Stop asking!! I need to stay here. I need to be silent!!!’ (#1, p. 17).

Mum always used a lot of exclamation marks when she wrote about her silence. She would jab the dot in a way that felt like an actual exclamation, as if she really was shouting. Sometimes she did it so hard that she stabbed a hole in the paper, and in the reproduction of notebook #1 you can see several places where these appear as slightly larger, darker circles (see #1, pp. 23, 34, 45, 56, 59 and 72).

But on the afternoon of my birthday that was all ahead of me and, as far as I can remember, in response to the declaration that she needed some peace and quiet I just shrugged and went to pick up the glasses. I was used to Mum’s eccentric behaviour. I remember thinking that Dad wouldn’t be happy. But that’s all I remember thinking. It never crossed my mind – and why would it? – that that afternoon marked a frontier in our lives. Because earlier that day, perhaps when she was singing ‘Happy Birthday’, or maybe when she was calling goodbye to my friends as they left my party, but certainly at some point during the day I turned thirteen, I had heard my mother’s voice for the final time.

2.

I don’t remember the sound of Mum’s voice, but I do remember when I began to forget it.

It was only a few days after she moved into the tent, and I was still convinced it was just a temporary thing, when I woke up in the middle of the night and knew straight away that something was wrong. At first I couldn’t work out what it was. I’d been feeling poorly all day and when I’d said I didn’t want any dinner Dad had packed me off to bed early. When I woke up everything was silent, so I knew it was after kicking-out time downstairs. I lay very still, listening to my breathing, trying to understand what had happened. I rolled onto my side, and it was then that I felt my pyjama bottoms sticking to my thighs. I got out of bed, plucking the material away from my skin. I went into the bathroom and pulled the door shut really quietly, so as not to wake Dad. Only then did I put the light on.

I couldn’t believe the amount of blood. If I hadn’t known better I might have thought I’d been stabbed in my bed while I slept. No one had warned me that I might bleed so profusely. I pulled off my pyjama bottoms and examined the streaks of reddish-brown on the inside of my thighs. Mum had prepared me well, thankfully, so I wasn’t scared by the sight of the blood that night.

I was officially a woman now. That’s what Mum had always said while making sure I knew exactly what to expect when puberty hit. She was full of aphorisms on the subject: ‘Embrace the hormones, Emilia, you’ll miss them when they’re gone’ and, about period pain, ‘Proof women are the stronger sex, Emilia’ and ‘Tampons, best invention ever’.

‘Ready for when you need them, Emilia,’ she had said some months previously, waving a selection of sanitary products under my nose before heading off with them towards the bathroom.

I ran some water onto the corner of a towel and scrubbed my legs, belatedly realising that perhaps it wasn’t the best idea to use Mum’s cream towel. She was going to freak out when she saw it. After I had cleaned myself up, I pulled open the bathroom cabinet and shoved various pots and packets around, but there was no sign of anything that looked like a sanitary towel. Bundling my pyjama bottoms up in the towel, I put the whole lot in the laundry basket. I would put another pair of pyjamas on, then go and find my mother. Whatever this living-in-a-tent, no-talking thing was about, when I told her what had happened, Mum would come home.

I crept down the stairs. By the time I reached the bottom, Midge was waiting for me, tail thumping. There was enough moonlight for me to pick my way through the beer garden, but even though I knew that stretch of grass as well as I knew my own bedroom, the dark trees reaching overhead and the garden furniture looming towards me out of the blackness still made my breath catch. Midge bounded around, sniffing everything he could find and snorting happily. The garden smelled different at night, damp and earthy – less brewery and more overgrown woodland. Outside the pub a car crawled down the street, a brief flash of headlights lighting up the rusty swing in the corner of the garden before sliding off the hydrangeas. As the sound of the engine faded, I realised I was holding my breath. I let it out and carried on towards Mum’s tent.

A light flickered inside the canvas. The day before, she’d written me a note – candles and matches, please. I could only find scented candles she’d been given as presents and I’d delivered them along with the frozen pizza that I’d heated up for dinner. Mum and Dad had always taken it in turns to do the cooking, and as soon as I was old enough, it became my job to deliver a plate of food to whichever one of them was serving in the pub. If they were lucky, and things were quiet, they would be able to pull a stool round to the side of the bar and sit down while they ate. On busy nights, they would just grab a mouthful between pulling pints. But with Mum in the tent and Dad behind the bar, we’d been reduced to eating whatever I could find in the freezer.

The candlelight inside the tent meant Mum must be awake and I was about to poke my head inside to find out when I heard Dad’s voice. I stopped so suddenly that Midge bumped his nose into the back of my leg and we both sat on the grass to listen.

‘… what do you want me to do?’ Dad was saying. He sounded angry. There was silence, and when Dad said, ‘That’s rubbish,’ I realised that Mum must be writing things in my notebook then showing them to him.

‘What about Ems?’ Dad asked. More silence. ‘Of course she needs you, Rachel. You’re her mother.’

One of the many lovely things about my dad is that he hardly ever gets angry. Back then he would always say that, with running a pub, you have to learn to swill your anger away with the slops because when people get drunk, they speak so much rubbish that you have to let it wash right over you. But that night, whatever Mum was writing clearly wasn’t washing over him.

‘This is ridiculous. Why won’t you speak? What am I supposed to say when people ask what’s going on? I know things haven’t been great between us, Rach, but seriously, how can you think this is going to solve anything?’

I’d known they’d been going through a bit of a ‘rough patch’ as Mum had called it, but to be honest, loads of my friends had parents who genuinely appeared to hate each other, and compared to them Mum and Dad’s bickering didn’t seem so bad. Gran always said that my parents were ‘meant to be together’, that they had ‘found their way back to each other against all the odds’ and that they ‘went together like peaches and cream’. Looking back now, it’s obvious she only said those things because that’s what she wanted to believe, and of course Gran had played a major part in Mum finding her way back to Dad. Gran was Dad’s mum, but she and Mum were so close that people who didn’t know often thought she was Mum’s mum.

Of course, people who didn’t know better also assumed Dad was my biological father.

I can’t remember a time before Nick was my dad. It was never a secret, but it was also never a big deal. He is the only father I have cried in front of, been embarrassed by and given Father’s Day cards to. He’s the only father who swung me up on his shoulders, so high that I cried with disappointment when my outstretched fingertips didn’t brush the clouds. He’s the only father who taught me to ride a bike and told me funny stories to distract me while the doctor set my arm after I fell off the swing. He is the only father I have ever loved. We’ve never talked much about the fact that Nick isn’t actually my biological father, but I do remember him telling me when I was really little that if he could pick any child from anywhere in the whole world to be his child, he would pick me every single time. I like to believe that’s still the case, even now, and although I’ll never know whether things would have turned out differently for my mother if she had chosen someone else to be my father, I honestly believe that the best decision Mum ever made was choosing Nick to be my dad.

Here’s something no one knows about Mum. When I was a kid, she used to tell me stories about my biological father, my bio-dad as she called him. I suppose she thought it was funny to make things up, but I was never comfortable with it, not least because I felt like we were being disloyal to Dad. The first time she made up a story about my bio-dad, Dad was downstairs and Mum had put the news on the television in the kitchen while I ate my tea – I must have only been seven or eight years old – and there was an interview, probably with a politician. I vividly remember shovelling baked beans into my mouth when my mother flicked her hand casually towards the television and said, ‘Oh, look, there’s your bio-dad.’

I can still hear the sound of my fork hitting the plate and feel the baked beans dribbling off my chin and plopping onto my T-shirt. I looked from Mum to the television and back again. It could only have been a matter of seconds before the programme moved on and the man disappeared from the screen.

‘That’s him? That’s my bio-dad?’ I asked.

‘Yep,’ said Mum, flicking the kettle on.

‘Is he famous?’

‘Of course, darling, why else would he be on TV?’

‘Does he know I’m watching him?’

‘Don’t be silly, darling. How could he possibly know that?’

While she busied herself making a cup of tea, I thought about what I would say at school the next day. Olivia and I were already best-friends-forever by then and she would be so jealous because the previous week we’d had to write about what we wanted to do when we grew up. I wanted to be a vet so I could spend every day cuddling puppies like Midge. Livy – always a bit of a rebel – hadn’t written anything; instead, she had drawn herself inside a television set because she wanted to be a presenter and wear a different outfit every day. Livy never did make it in front of the camera but she is a high-powered City lawyer so she hasn’t done too badly. You probably already know I’m not a vet.

Back then, for eight-year-old me, it was exciting to see my bio-dad on the television at first; however, by bedtime it suddenly didn’t seem exciting any more. It was scary. Would bio-dad want to take me away from Dad? Would Dad still want to be my father when he found out that bio-dad was famous? In the end, I was in such a state that I got out of bed, trailed down the stairs and stood at the end of the bar crying, waiting for one of my parents to see me. I was only allowed to do this if there was an emergency, but I’d worked myself up into such a state that I was convinced that bio-dad was about to arrive any second to steal me away.

Mum was the one who led me back upstairs, sitting on my bed and waiting for me to calm down enough to tell her what was wrong.

‘Oh, darling,’ she said, and actually laughed. ‘He’s not your bio-dad. You’re a big girl now – you really should be old enough to understand when someone’s teasing you.’

I didn’t understand. ‘So who was the man on the TV?’

‘Who knows? I wasn’t even watching it.’

‘But why—?’ I stopped. Back then I didn’t even know what question I wanted to ask.

Now when I think about that day, I have no problem coming up with questions I’d ask my mother if she was still alive. There were so many little ‘jokes’ about who my bio-dad was: astronaut, actor, author, criminal, musician – anyone, it seemed, who caught her imagination when she was in the right mood. I could start my questions with ‘Why would you joke about something like that?’ Or ‘Why on earth joke about it to your own child?’ And, let’s face it, she might have pretended they were jokes, but essentially, each time she made up stories about my bio-dad it was a lie, so, ‘Why would you lie to me about something so important?’

That night, what I remember most vividly was the relief I felt when I understood that the man from the television wasn’t going to come and take me away. I was left with an abiding hatred of baked beans, though. To this day they taste of lies.

In the tent, candles flickered, and the silhouettes of my parents against the canvas flickered too. I shivered and felt around for Midge, wanting to cuddle up to him, but patience was never one of Midge’s virtues. Out of the dark his shadow loomed against the tent and he pushed his way inside.

‘Midge? How did you get here? I left you in the house…’ Dad stuck his head out of the tent, flashing a torch across my face. ‘Ems? How long have you been there?’

I shrugged and said, ‘Not long.’

‘Why aren’t you in bed?’

‘Something’s happened. I need Mum. Don’t worry, Dad, she’ll come home now.’

I stood up and walked over to the tent, and it was only when I heard Dad gasp that I looked down and realised that a second pair of pyjama bottoms were now bloodstained. Midge sniffed my crotch but I pushed him away, half-crouching in the entrance to the tent, and looked at Mum. She didn’t seem particularly pleased to see me.

‘Mum, I’ve got my period. I need the things you bought, but I can’t find them. Please come and help me?’

At that point, there was absolutely no doubt in my mind that she would get to her feet, reach for my hand, smile at Dad and say something like, ‘Well, this has been fun, but it’s time to go back to the house.’ We would walk through the beer garden together while she told me how proud she was that I was now a woman. We’d go in the back door, up the stairs, she’d show me where the sanitary towels were, then she’d see the mess I’d made of her cream towel and get annoyed, but when I told her that my tummy was hurting really badly, she’d make me a hot-water bottle and a warm drink and sit on the end of my bed until I felt better.

I was completely certain that’s what Mum would do and not one bit of me expected her to do what she actually did.

First, she looked at me. I mean properly looked at me, from the top of my head, down over my too-small Hello Kitty pyjama top, pausing for a moment on the bloodstained pyjama bottoms before carrying on down to my feet. Watching her looking at me was the weirdest experience: it was like being examined by a stranger who had never seen me before, as if she was trying to decide what she thought of me.

Then Mum reached for the notebook. Dad’s breathing was really loud and I thought he was going to shout at her, but he just squeezed his lips tightly together. Mum only wrote for a few seconds, then held up what she’d written for me to see. I had to squint to read it.

My bedside table. Second drawer down.

That was it. That was the extent of my mother’s help.

Sometimes I wonder if I was so hurt by what my mother did that night – or, more to the point, didn’t do – that I deliberately made myself forget what she sounded like because, by the start of the school holidays a few weeks later, I was beginning to recognise the ache deep inside me when my period was due, I was using tampons and I could no longer remember the sound of my mother’s voice.

3.

From: Nick Wright

To: Emilia Morris

Date: 20 February 2022

Subject: Mum

Hi darling,

Lovely to see you yesterday. I hope you didn’t get caught in that downpour on your way home.

Look, I’m sorry the conversation got so heated. I know I probably had too much wine, but I am genuinely concerned what the Community might do when it finds out you’re writing a book about Rachel. Having said that, I do understand why it’s something you want to do, so I’ll try and fill in some background for you, although it’s surprisingly difficult to remember what our lives were like before.

I guess I always knew I was living on borrowed time with Rachel. I was never going to be enough for her. I mean, your mother was gorgeous and funny and clever, and what was I? A lonely divorced bloke with a pub that I was barely managing to keep above water. Of course she wanted more than I could give her.

I think you know that Rachel and my mother, your gran, wrote to each other. Gran loved writing to people, sitting at that old desk of hers with a cup of tea and a teacake (always lightly-toasted, heavily-buttered, do you remember?) writing letters with her Basildon Bond paper and matching envelopes. She wrote to so many people: school friends she hadn’t seen for decades, people she’d met on a beach in Dorset thirty years earlier, and strangers she’d sat next to on the train and wound up talking to, swapping addresses on scraps of paper. Do you remember that time she joined a pen-pal scheme that matched her with Japanese women who wanted to practise their English? She didn’t like those airmail letters one bit. Always complained how thin and slippery they were, like council toilet paper, she said.

The point is that I wasn’t particularly surprised when I found out that my mother and Rachel had been writing to each other. I imagine Gran trotted out her usual comments on my failed marriage (she used to call it my starter-marriage!) and no doubt she told your mum that I’d put it behind me. I had, as it happens, and of course I didn’t mind at all when I found out they had been in touch with each other – it just would have been nice to know what they were planning.

Your mother arrived late one evening, just as I was locking up. The last time I’d seen Rachel she’d been eighteen, brunette and experimenting with a perm. A decade later, standing in the doorway of the pub, her hair was short, blonde and spiky, but other than that, she looked just the same. ‘Am I too late for a drink?’ she said, or something like that, but I just stared at her. Rachel Morris. There. In my pub.

You know she was my first girlfriend, but I don’t think I’ve ever told you how your mum broke my heart a few weeks before she went off to university. She sat me down and told me that she needed to unburden herself. At first, I honestly thought she was worried that her bags would be too heavy when she left for university (it’s no wonder she split up with me!). It was only after a while that I realised she was talking about me. I was the burden. Your mum wanted to unburden herself of me.

I spent the rest of the time before she left alternately telling anyone who would listen how much I hated her and begging her to change her mind. Eventually the day came that a taxi pulled up outside her house, and when it drove away, I was certain any chance of getting back together with Rachel Morris was gone forever. Indeed, until the night she turned up ten years later, she never did come back. She didn’t come home for the first Christmas, and then her parents moved away so she had no reason to return to Chalkham. But somewhere down the line, she’d acquired Gran’s address, or Gran had acquired hers, and together they’d hatched the plan that led her to the doorway of The Wild Boar.

Eventually I stopped staring and gave her a hug, and when she hugged me back, I remember thinking that we fitted together like we were still eighteen. This is where it gets tricky, Ems. I want to be honest, but this isn’t the sort of stuff a father should talk about with his daughter. I’m not even sure it’s relevant, but then again, perhaps everything your mum did was somehow relevant so I’m going to try and tell you as much as I can without causing either of us to feel too embarrassed to ever see each other again!

There was a bit of chit-chat. She was evasive, wouldn’t tell me where she’d been living or what she’d been doing or why she’d come back to Chalkham. Thinking about it now, I can see how carefully she’d planned it. God, this is so difficult – I’ve just had to pour a large glass of wine to fortify myself! What I’m trying to say is that after my first marriage broke down it was difficult meeting women. You know what it was like in the village – everyone knew everyone, I was working every evening, and of course Gran knew that better than anyone. That’s why she encouraged your mum. She knew I was lonely. And she had always loved Rachel.

It would be wrong to say that Rachel took advantage of me. After all, I was a grown man and entirely willing, but (and it’s an important but) there’s no way I would have tried it on with her that night. No way at all. But your mum knew what she wanted, and she did what she needed to do to make sure she got it. Afterwards, I remember we sat on the floor, leaning against the bar, and drank vodka straight out of a bottle. That’s when she told me about how she and my mother had kept in touch and how, when Gran heard how difficult things were for Rachel, she took it upon herself to suggest that Rachel come and live with me.

I can practically see Gran’s letters. You and Nick were always so close, she would have written. Something like that. There’s a spare room at the pub since I moved to the cottage. He’d love to see you. There was no doubt that your gran was right – it was fantastic to see Rachel – but I just wish, looking back, that I’d had at least some sort of say in the decision. It doesn’t do much for your self-esteem to realise how easily you’ve been manipulated. Although, given everything that’s happened, it’s probably the least of my issues!

That first night, before we finished the vodka, your mum said something about the spare room being fine, but if there was room in my bed…? Goodness knows what rubbish I babbled, but by the time we got up off the floor it was all sorted and your mum was there to stay. She went to get her stuff from the car, and the rest of the story you already know because I’ve often told you about how Rachel only had two things with her the night she moved in. She had a heavy bag over her shoulder, and in my rush to take it from her I barely noticed the second thing, wrapped in a blanket and held close to her chest. It wasn’t until Rachel folded down a corner of the blanket that I saw you. Emilia. Beautiful, perfect baby Emilia. My Ems.

And of course, that was that, and despite every single thing that has happened since, I can honestly say that the best day of my life was and forever will be the day your mum brought you to live at The Wild Boar.

I think that’s about as much as I can manage at the moment, Ems. I’m going to send this before my nerve fails me and then I’m going to have another large glass of wine.

Don’t forget dinner here next Friday. Looking forward to seeing you – 7 p.m. Don’t be late!

Love,

Dad

4.

By the time school finished in July 2003, Dad and I already knew things weren’t going to go back to how they were, even if we weren’t admitting it out loud. Gran kept saying things to me like, ‘Your mum just needs some time out’ and ‘It’s difficult being a woman in today’s world’. Gran was nothing if not practical, though, and as soon as she found out what was going on, she vetoed our frozen-pizza diet and hauled bags of groceries into the kitchen, muttering darkly about rickets and scurvy and malnutrition. The tension I had been carrying around with me for weeks eased slightly. At least with Gran taking care of the cooking we were eating proper food and Dad could concentrate on the pub.

I missed Mum. I missed snuggling with her under my duvet, gossiping about the latest intrigues in my thirteen-year-old life. I even missed her nagging me to get on with my summer reading project. Of course, I could go and see her whenever I liked – I only had to walk down to her camp (which is what Dad and I called it, still desperately pretending it was some temporary, fun activity) – but it wasn’t the same. It would never be the same.

Looking back, I can see how I began pulling away from my mother right from the start. It was hardly surprising. For one thing, there was her refusal to speak; although, at first, her silence was treated almost like a joke. I’ve found a mention of it in the archives of the Mid-Hants Examiner1, and as far as I’m aware, this is the first time Rachel was mentioned in the media. If the paper had had any clue what she would become they would have had the scoop to beat all scoops, but instead, in three short paragraphs under the headline ‘Silence in Chalkham – Pub Landlady Calls Time on Talking’, her silence was variously referred to as ‘a teasing puzzle’, ‘a disquieting quiet’ and ‘an aspiration for henpecked hubbies everywhere’2.

Little wonder the Mid-Hants Examiner is no longer in print.

Several of Rachel’s biographers have suggested that her silence was merely a public-facing protest, speculating that she must have spoken in private, at least occasionally.

There can be little doubt that Rachel communicated verbally during the eight years prior to the Event. The idea that she could mastermind the explosive expansion of her Community, undertake the organisation of the many protests that took place during 2007–2010 and coordinate the complex logistics required for the multiple Event sites without speaking a single word stretches one’s credulity almost to breaking point.

(Speak No Evil, Dr Jasmine Peterson,Leaping Press, 2018)

All I can say is that from the moment my mother left home, I never heard her utter so much as a syllable. Not to me, not to anyone.

For Mum’s birthday that year I gave her words. Gran bought some stiff cardboard that I cut into rectangles, and on each one I wrote a word in marker pen: yes, no, thank you, please, hungry, thirsty, happy, sad, well. I tried to think of handy answers to questions so when I went to see her I could say, ‘Hi, Mum, how are you feeling today?’ and she could hold up the card saying well, followed by the one saying thank you.

The thing was, I couldn’t write the words I really wanted her to hold up. I wanted her to answer questions like ‘Why are you living in a tent?’ and ‘When are you coming home?’ and ‘Why won’t you speak to me, Mum?’ but when I asked her those questions (which I did frequently) she’d just look at me, silently.

Once the first notebook – the one she had stolen from my room – was full, Gran and I had gone to WHSmith to buy Mum a replacement, and that is the official notebook #1. Later, Rachel generally used more expensive notebooks (all twenty-nine of them are on the table in front of me and #27 is a particularly lovely example: green leather, hand-tooled and bound by one of the Members, Rachel’s initials beautifully picked out on the cover in gold leaf ) but I’ve got to hand it to WHSmith, their Mega Jotpad has stood the test of time. There are two brown, interlinked circles (presumably from the base of a mug) on the front cover, which has become detached from four of the wire rings, and there is what looks like a grass stain on what remains of the rear cover, but that’s it for damage.

Flicking through it now, I’m reminded just how fast Mum would write, often scrawling at angles across the page before spinning it round for me to read. ‘I am listening