Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

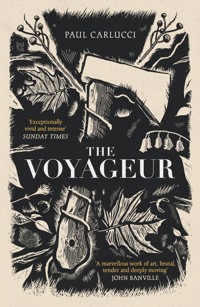

'Exceptionally vivid and intense' Sunday Times 'A marvellously dark yarn' The Spectator 'A swaggering debut' Daily Mail Everyone expects at least a little bit of deception... Alex is a motherless stockboy in 1830s Montreal, waiting desperately for his father to return from France. Serge, a drunken fur trader, promises food and safety in return for friendship, but an expedition into the forest quickly goes awry... The Voyageur is a brilliantly realised novel set on the margins of British North America, where kindness is costly and the real wilderness may not be in the landscape but in the desperate hearts of men.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 551

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by the author

The Secret Life of Fission (2013)A Plea for Constant Motion (2017)The High-Rise in Fort Fierce (2018)

To Jessica Murphy,with infinite love.Long may we coze.

Contents

Part I: DégagéPart II: FoutuPart III: Nouvel EspoirPart IV: Au RetourÉmancipation: The years that followedAcknowledgmentsPart I

Dégagé

Late Spring, 1831

1

The whispering had started a few days before, but that morning, as the men clambered up the stony beach and blackflies besieged them, they spoke of him openly, and with anger. Serge had come down with consumption. He’d slept with dogs in the streets of Montréal and now the brigade would have to leave him behind before his condition spread, if it hadn’t already, and tant pis, because the man was a dreamer and a sodomite and he was too old besides.

They’d left Lachine six weeks previous, about twenty men and an Algonquin woman who made their food and patched their boats and suffered their lechery. They brought their French into the wilderness and imagined it might cling to the rocks in the rivers and wash up on the banks as well. Their red toques were tattered, their sashes torn, and their canoes heavy with kegs of rum and barrels of gunpowder and many dozens of crates full of smaller items to trade for fur at Fort William. They carried as well a collection of axes and fiddles and blankets and rope. They’d already paddled four hours that morning and it was eight o’clock when they stopped for breakfast on the cliff-enclosed banks of the Rivière des Français.

There were rumours about Serge. He’d gained his spot on the brigade after beating an officer of the Hudson’s Bay Company in poker, which seemed a plausible story because he’d brought two unsullied blankets with company stripes as well as several bottles of premium rum and he quietly refused to portage the heavy boats and the lighter ones too. He was slowing them down. They should’ve been at the fort by now, guzzling rum by the keg, but Serge carried only a dozen pounds of supplies at a time and never once did André l’avant take him to task for even the most outrageous lethargy or fatigue, and so upsetting was this double standard that soon there were angry rumours about André as well: he’d entered into a secret agreement with the company’s senior officers, des angluches to the rotten last; he’d disavowed his Canadien heritage and would become a clerk once they returned to Montréal; he wasn’t a leader at all, just another special case like Serge, and like Serge he’d bring them to a broken end.

Their third source of discontent was the boy. They were all sick of this boy, whose name was Alex. He’d come along with Serge like the older man’s blistering cough and he’d been sullen and reluctant at La Pointe au Baptême, where all men new to the trade were soaked in the waters that flowed lazily past an enduring stone church, and since then he’d bothered them more and more. He was skinny and feeble and fragile, and they laughed at the little tufts of boyish beard that grew like windswept shrubs on his bony cheeks. They gave him only the worst servings of salt pork, pieces so tough and chewy he had to swallow them whole. They called him cul crevé right to his face and among themselves they agreed it was partly the boy’s fault they’d let Serge’s sickness settle so close, because the two had been sleeping together in a deerskin tent, not under les canots with the rest of the men, and so for a time it was easy to ignore Serge’s wretched hacking, until gradually the situation became clear and they could abide mortal danger no longer.

It was the first day of June and the heat was rising despite the persisting rain and they longed for the cool of early May, when in some places there was still ice on the shores and snow in the forest. The men lit their pipes and handed out pemmican and Serge slung a deerskin bag over his shoulder and motioned for Alex to follow as he lumbered down the beach. They had affairs to discuss. The sand gave way quickly to stone and behind them was a forest of ragged pine and across the water a large cliff, the summit of which was bathed in a lone shaft of yellow sun. They found a spot with a wide view of the dark and glassy water, and Serge unfolded a bearskin and spread it over a rounded slab of grey rock. A loon hollered from mid-river and the forest behind them seemed somehow ill. Serge took from his bag a flask of rum and passed it to Alex, who drank and passed it back.

‘Tu vois,’ said Serge in his mumbled French, ‘they won’t let us travel with them anymore.’ He issued a wet, snapping cough and a curl of red foam shot over his lips and clung to his beard before he wiped it away.

Alex looked from Serge’s damp and shiny eyes to the wilderness surrounding the men and their canoes. What would they do out here? How close were they to Fort William? Days away, maybe more, ample time to die on the banks of the river or in the forests that crept away from either side.

Serge put his arm around Alex’s shoulder and gave his tiny frame a squeeze. ‘T’inquiète pas, Ali. First, we smoke my pipe. Then I’ll challenge André to a fight and win some supplies, don’t doubt it. I only need a few days’ rest, and after that we can make our own canoe and continue to the nearest post. We’re not far from Fort William now.’

Alex looked at Serge’s wide and hairy knee emerging from torn trousers. He wanted to reach out and touch it but was worried the men would see this and become even further enraged, so he took up one of his own hands with the other and worried them in his lap. ‘But what if you lose?’

The men up the beach had formed a mob around André. They shouted and spat and pointed at Serge and Alex and it was clear they’d had enough, what they wanted now was violence.

Serge watched this and dredged his throat and the sound of blood in his airway was evident. ‘On va gagner, mon gars. On gagne t’jours.’ He gave Alex’s shoulder another squeeze and unfolded his pipe from his sash and a pouch of tobacco, and together they smoked and drank and watched as André l’avant conceded to the demands of his brigade.

They’d met in Montréal ten months previous. Stocky and bearded and dressed in buckskins, Serge was doubled over in the midday street with his hands on his knees vomiting in the gutter outside Plus Jamais Tavern. Next to it was the squat brick grocery store where Alex worked as a stockboy and a cleaner and a clerk. The street was quiet and the sun blazed on the cracked spruce shingles of nearby houses and a brothel and a spate of slumping taverns. They weren’t far from the port, and when the wind was wrong the neighbourhood stank of fish.

Alex was picking rotten apples out of the display crates on the creaky wooden porch so they might be sold at a slight discount to an orphanage, and the sorting was a slow business, painful, because le patron had caned his knuckles only a few days before, this after a band of sooty delinquents stole a sack of potatoes and Alex cowered as they leapt off the porch and scattered in all directions.

Le patron was Lewis Anderson, the son of a Scottish railroad baron, and the grocery store was a gift from his father. M. Anderson was a thin man, barely twenty-five, and he wore suspenders and spectacles and smoked a pipe with an ivory handle. He’d hit Alex before, half a dozen times at least, and for any reason at all: dust on top of the cabinets, a jar shelved with the label facing inward, too many flies on the display tomatoes when the heat was high. Each time, Alex flinched and winced and felt his eyes sting with tears, but he didn’t grieve until he was alone and curled up on the straw-stuffed mattress that M. Anderson allowed him in the back room.

When his papa returned from France, he’d have his revenge. Whereas Alex was soft and slight, his papa was a logger and a fisher and a Catholic with powerful arms and the hands of a giant. Alex imagined those massive fingers clamped around M. Anderson’s throat, squeezing, and he imagined le patron’s feet in their polished shoes kicking above the boards of the floor. He imagined how he’d snap the broom handle over his knee, the sound it would make as he threw it to the floor, and then he’d walk out of the store next to his papa and on the ground behind them le patron would lie weeping, the stem of his pipe broken neatly in two.

But it had been two years since his papa had boarded a sail-ship and Alex had yet to receive a letter from Paris or anywhere else. He was patient because his papa told him he’d have to be: it would take time to earn enough money to come back and buy them a plot of land in the countryside. Alex would have to work hard in honour of his maman’s memory. She died a few months before his papa went to Europe, which was sad, even his papa agreed, but the family had known death before Alex was born – his brother, after whom he’d been named, died at just six months old. His maman never recovered from the loss, and it was precisely that weakness that left her open to infection, but Alex and his papa couldn’t allow death to distract them, not if they didn’t want to fall sick themselves, and this was a lesson he’d do well never to forget.

The day before his papa boarded the ship, the two of them walked to the Port of Montréal and his papa put his hand in Alex’s hair and closed his fist and told him to take a good look around, not at the ships that were due for voyage or the well-heeled people who walked the gangplanks but at the teen-aged filth fighting one another for a chance to sell newspapers or fish or bread and the younger kids curled up on mouldy blankets in the shadows along the wharf. His papa said he’d made an arrangement to keep his son from such a terrible fate. Alex wouldn’t be paid and he’d have to work for a man who was both a Protestant and an angluche, but he’d have a place to sleep and a bit of time to himself, and that was more than most people could expect in a British colony or anywhere else.

After his papa left for la mère-patrie, Alex spoke hardly at all. His hair grew long and thin and he hid behind the limp brown strands that hung in his face. He endured the abuse and was grateful for the mattress. He waited for his papa and didn’t think life could happen any other way, not until the porch planks creaked under Serge’s considerable bulk and the air filled with the stench of puke and sweat and shit.

‘Donne-moi’s’une pomme, mon gars,’ said Serge in a plodding slur. ‘Tout’suite.’

Alex had dealt with drunks before. He’d seen men pass out in the mud and piss themselves leaning against the walls of the grocery store and accost him for bread or fruit or whatever else they thought he might give out, and so he knew that the best thing to do was to ignore them, to look away, and if necessary he would go inside and bar the door, and he was about to do exactly that when he saw the glint of copper in Serge’s outstretched palm, so in French he said, ‘You can take your pick, sir.’

Serge’s knuckles were plump and scabby. His nails were chipped and cracked and stuffed with dirt and blood. He chose a healthy apple and bit into it and wiped his lips with his sleeve. He was short, barely more than five feet tall, but wide in the shoulders, and his beard was long and matted and so was his hair and his nose stuck out of his face like the blade of an axe. Alex knew that men like this lived in the swamps and shanties along the St. Lawrence. They were thieves and worse and they came to town to drink and gamble. He knew he should be afraid, not just of Serge but also of M. Anderson, who would be furious if he came out and found them chatting. But there was something charming about Serge, a curious warmth, and maybe it was like approaching a wood stove on a frosty night: you got close because you didn’t want to be cold, but too close and you’d smell your flesh when it burned.

Serge finished the apple and threw the core in the street and told Alex his name as if they were passengers in a carriage. He gave Alex a coin for the apple and then another coin, which he told Alex to keep for himself, and he said, ‘You work hard, but you aren’t paid much, am I right?’

Alex nodded and opened his mouth to speak but heard footsteps from inside the store and knew M. Anderson was coming to check on him, so quickly he turned his back on Serge and slid the coin into his pocket and pretended that he was ignoring this drunken brute from the tavern next door.

‘You there,’ declaimed M. Anderson in his unwieldy burr. He appeared in the doorway with one hand in his pocket and the other pinching a pipe in the corner of his mouth. ‘You will remove your torn-down wreck of a self from this property lest the consequences be severe. Have I made myself clear?’

Serge swayed on the porch and licked his lips and dredged his throat and spat in the street, and a tiny cloud of dirt flew up where the gob hit the ground. Alex turned from this sight to the apples, the soft ones with brown craters and the crisp ones with shiny skins. He felt tension coming off M. Anderson like wind blowing off the river, and he glanced at the man and saw his florid face and a vein bulging in his neck and his pipe at an upward angle because he was crushing the stem between his teeth.

‘Crystal clear,’ said Serge in English. The porch creaked as he stepped into the street. ‘But I will be back, you know this, because I like your apples very much and I don’t want to find you bruise them. I won’t like it one bit. Have I made myself clear?’

Alex turned his focus to the apples once more. He heard Serge tromp away and M. Anderson hesitate in the doorway before clearing his throat and tapping the embers out of his pipe and wordlessly going back inside. Once le patron was gone Alex peered down the street to catch a final glimpse of Serge, who lingered in the door of the tavern. The two made eye contact and the latter waved before staggering back inside.

On the beach they fought for maybe five minutes and thrashed their way from the rough sand to the water. They looked tiny in the lee of the far-shore cliffs and a crow took flight from an emaciated pine and wheeled above them before croaking downriver. It was obvious to Alex and everyone else that André had been waiting for an excuse to make violence with Serge and obvious that he’d win from the first punch, which landed hard and loud in the pit of Serge’s right eye, hard enough to pump a shot of blood from the older man’s brow, and more blood streamed down his cheek and into his moustache and beard.

Alex took a step forward but had no real intention of interfering on Serge’s behalf, he was too scared, but a few of the voyageurs found his movement excuse enough to push him to the sand and kick him in the ribs, and even though they were only wearing moccasins Alex felt the wind sail out of him and he spent the last minute of the fight gasping, unable to cry out as Serge fell to his knees in the water but remained stubbornly upright while André threw one fist after another into his face, knocking clear a bloody tooth and finishing his barrage with a punch to the throat. Serge’s eyes bulged and he clamped his hands over his neck and fell back in the shallows, wheezing, defeated, and with one last effort he crawled out of the water and onto the beach, where he brought his knees to his chest and clutched his crumpled throat.

It hurt to breathe and Alex held his ribs and felt the birdlike frailty of his frame beneath his palms. He crawled across the pebbly beach and kneeled over his fallen friend and tried to assess the wounds, but they were too hard to distinguish in the gruel of blood. He only knew that his friend’s great blade of a nose had been broken and that this would cause pain as the consumption settled deeper.

Above and around him the men were laughing and quitting the beach. They loaded les canots and splashed into the shallows and pushed the boats into the deeps. It seemed to Alex that he and Serge would be left there to die with nothing, but then André loomed in his torn-open cotton shirt cascading water and the front all spattered with blood. The flesh of his chest was twisted into scars that looked like burns, and in each of his muscled hands he held a canvas sack, both of which he threw on the beach as he said, ‘For you, I feel pity. I feel pity that this man has devoured your innocence and sorry you can never have it back, sorry that you are cul crevé and that you must die on this beach with an emissary of the Devil. So I give you these few supplies and in return I pray le seigneur spares me and my men your deadly disease.’

Serge muttered something unintelligible. His breathing was laboured and his eyes were glassy and blood streamed from his nostrils. He shifted in the sand, turning to watch the Algonquin woman hurry out of the forest, where she’d been gathering sap to patch les canots, and as she gave them a pitying look he clenched his fists and yelled, ‘M’aide-nous, salope sauvage!’

André snorted and turned and walked down the beach and into the shallows, the woman sloshing after him as he sank to his waist. They mounted one of the long boats and André shouted for the men to dig deep their paddles and heave off into the morning. The brigade broke into song and was soon out of sight, and the water turned dark and calm once more.

M. Anderson didn’t spend nights at the store. He lived in the suburbs in a large house with his father and mother and siblings, and their neighbours were of the finer stock who continually arrived from England: politicians, judges, aristocrats, barons, so many of these people as well as their inferiors that les Canadiens were beginning to lose their majority in cities like Montréal. Alex had nights to himself, just as his papa had promised, and some of them he spent cross-legged on his mattress drawing passable pictures of the St. Lawrence with a piece of coal and scraps of wood he found in the alleys around the neighbourhood, while during others he drew not much of anything at all, just took a large lump of coal in each of his hands and moved them rapidly and at random across his makeshift canvas as he looked up at the shadowy rafters and closed his eyes, thinking of his papa clutching his hair or his maman cradling his shoulders or M. Anderson striking his face, and when he looked down again all the swirls and whorls and smudges and smears seemed to say something about how he felt, about how fast his hands had moved and for how long and why.

He seldom ventured outside, not even to Mass. He knew his maman would’ve urged him to go to la Chapelle Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours to take Communion before the fabled statue of the Virgin Mary, for there was power in the flow of her robes and warmth of her open hands, power that had lessened the plight of sailor and beggar and whore, and when his maman was alive they took the Sacrament and attended the grand Masses, most of which were delivered in English to cater to all the Irish and Scottish who’d been filling the pews, and so it was doubly important for a young Canadien to make himself present in the congregation – the church was a symbol of New France, not Great Britain, they couldn’t have everything even as they thought they had it all. But Alex didn’t like being alone in the city. There was no one to protect him and the grey stone buildings soared and the muddy streets sucked at his feet and he’d jump at the sudden splash of a horse’s hoof. He found the people tense and there were smells that made him gag and unnaturally black shadows trailed behind him like smoke from the chimneys. It was safest in the back of the store, where sometimes he prayed, and whenever he did, he apologized to his maman for not attending la Chapelle and once he thought she expressed forgiveness when he knocked a large jar of preserves from a top shelf; the glass didn’t break and M. Anderson failed to notice the noise of it striking the floor, so Alex was spared a beating.

The room at the back of the store was small, barely big enough for the mattress and a few shelves, and there was a little window above a door in the back wall but no view because the hotel across the alley rose up too high. When he had to empty his bladder or bowels he went out the back door and used a bucket, which in the morning he poured into a gutter that ran past the tavern. The alley was where he cleaned his teeth with a rag and salt and also where he bathed, which he did once a week when M. Anderson gave him a small chunk of soap and allowed him to heat water on the wood stove. He’d recently begun using this soap and a dull razor to shave the sparse strands of hair on his neck and cheeks. He was grateful for the hot water but found in the winter it made no difference: his teeth still chattered from the cold.

His life wasn’t as comfortable as when his maman was alive and his father was always away fishing in summer and logging in winter and they lived in a coach house in the suburbs where she worked as a maid. It wasn’t nearly as comfortable, but it wasn’t so bad. Each night M. Anderson left him a heel of bread, a couple boiled eggs, and an apple, and on special occasions like Christmas Alex was given cheese and a few pieces of sausage. He disliked le patron but recognized in his situation a charity he wouldn’t have enjoyed if instead he’d wound up hawking fish or bread or newspapers down at the port, which was nevertheless his favourite thing to draw because of the smudgy ships sailing far away.

He didn’t label his drawings because he couldn’t read or write. When he was a boy his maman’s patron offered to put him through school, but only in English because what use was education in a dying language? Alex had already learned crude expressions from this man and his wife and their three sons, and so it wasn’t too late for him to grow into an adult unhampered by language or accent. But Alex’s papa came home from the coast and his hands were thick and scarred and he said Alex would be better off working around the property because he was too weak to work the bush and too frail to fish the river, and so he’d have to learn something practical if he was to have any hope of survival. Le patron acknowledged that every man had the right to shape a future for his son and though he’d pay no more for the service, he wouldn’t prevent Alex from helping his maman with her cooking and cleaning, and anyway English would impress itself upon him as it did all it encountered.

Tonight, Alex placed one of the coins Serge had given him on a piece of quartered hardwood and scoured the area around it with a lump of coal. When he removed it, the space beneath recalled a full moon and around it he shaded a midnight sky and below that the rickety wharfs of the port. He worked on this until it was finished and then went outside to shit in his bucket. The alley between the grocery store and the hotel was dark and muddy and full of trash, and Alex squatted and peered into the darkness but saw nothing. It was windy and the sky was black as filth and Alex knew a storm was coming. He wiped himself with a few torn pages of newspaper and was about to go back inside when he saw movement in the shadows and froze.

‘Bonsoir, mon gars, bonsoir.’ There was first the powerful stench of rum and then Serge’s face emerged from the gloom, but not entirely, rather just enough to see him smile through the wet tangle of his beard, and they stared at each other for a quiet moment.

‘You shouldn’t be here,’ said Alex, gathering himself in the door frame.

Serge chuckled and his teeth seemed to float in the dark. ‘Oh no? Says who? That Scotsman? M’en fous d’ce con. Don’t worry about him, my friend, all right?’ He stepped closer and Alex saw that his hand was outstretched and in his palm were several copper coins. ‘I need a place to stay. Just for tonight. We should be friends, nous deux.’

Alex knew he should close the door and lock it and maybe even go out front in search of a watchman, but that knowledge was dim and unconvincing in the face of Serge’s copper coins, and besides, this man had shown him kindness earlier that day and he felt he had to return the gesture, in particular because a storm was overtaking the area and what was the harm, there was no harm. M. Anderson wouldn’t be back until after sun-up and by then Serge would be elsewhere and no one the wiser. He nodded and Serge grinned and Alex felt a swarm of giddiness all through his chest. He smiled and cleared the door frame and Serge stepped inside, pressing the coins into Alex’s hand, more money than he’d seen in who knew how long, maybe ever. Alex felt he should sleep on the floor in return, but Serge shook his head when offered the mattress.

‘The floor’s fine for me, my friend.’ He put down his bag and began to unlace the throat of his buckskin shirt. ‘It’s the storm I don’t like. As for the ground, like you, it’s an old friend.’

Alex sat on the bed and tried to hide his drawing under the prickly blanket. ‘You’ll have to leave before the sun comes up.’

‘Ho-ho!’ cried Serge, and it was suddenly obvious how drunk he was as he reached out and snatched the square of wood from Alex’s fingers. ‘What have we here? You’re an artist! Mais ’garde ça, donc. It’s very good, my friend. It’s excellent.’

There was only a candle to light the room and Alex thought it was strange that Serge could see the drawing well enough to proclaim its merit, but he was happy as the first drops of rain tapped against the tiny window. He felt no embarrassment as Serge bent over and propped the wood against the wall by the door, where they could see the drawing in the staggering candlelight.

Serge lowered himself, arms wheeling, then fell backward, his skull thumping the floor next to a pile of scrap-wood canvases Alex kept by the head of the bed. He laughed and righted himself on his elbows, then picked up one of the drawings and angled it into the candlelight, squinting. Alex could see it was one of those drawings that wasn’t much of a drawing at all, one of those that was all smudges and smears, and he felt a sudden rush of embarrassment, but then Serge shook his head mournfully and said, ‘Ah, but you’re hurting, my friend, you’re sad.’ That drawing he placed delicately next to the first, and as the rain picked up there were now two drawings to behold.

Serge took off his shirt and made a pillow of it and curled up on the narrow strip of floor between the bed and the door while Alex blew out the candle and lay back on his mattress. The straw poked his back and he shifted until the discomfort went away.

The rain fell harder and harder and Serge’s voice croaked beneath it: ‘Would you like a drink, my friend, before you sleep?’

‘No, thank you.’

‘All right, then, bonne nuit.’

‘Yes, sir, bonne nuit.’

Alex had seen death when his mother fell sick and now with Serge beaten so bloody and at the same time so ill, he knew he was seeing it again. The morning had gotten old and a bank of clouds had arrived from somewhere beyond the looming cliff, smothering the sun and hanging heavy with rain. The beach was too exposed and they couldn’t stay where they were. They’d have to go into the forest and make a plan, but any such plan would be pointless because Serge was going to die, that much was clear.

André had left them pemmican and beans and a few biscuits made of water and flour, and there were also three tattered furs and a bottle of rum and an axe and a kettle. In Serge’s bag Alex found some dry touchwood and a chunk of flint and a piece of steel as well as a few portraits of Serge he’d made before they left Montréal. Serge coughed wetly from time to time but wasn’t conscious and Alex left him on the beach. He took their supplies into the trees and was again struck by the sickly appearance of the forest, its skeletal branches and tufts of moss turned brown and the cool air it held in its darkness. He gathered wood and made a fire, but the wood was damp and the flames powerless against the chill.

Alex returned to Serge and took a shot of rum and tried to rouse him, first by lightly shaking his shoulders then by cupping the crotch of his trousers, but Serge only coughed and blood bubbled between his lips. It was as if he were both on the beach and somewhere else, but mostly somewhere else, and Alex recalled a similar feeling at his maman’s deathbed.

Her patron had been generous enough to give her a room on the top floor of the house, and although it took effort to get her up the stairs, everyone knew they’d only have to strain once more when they took her body down, and this the doctor confirmed when he came to visit at le patron’s request. The room was more comfortable than the coach house and after work Alex took his meals at her bedside, watching her chest rise and fall and dabbing a wet cloth on her forehead. His father was away working, and although they’d sent a message to his camp he’d not yet come home or sent one back.

Alex spoke to his maman at length but didn’t tell her how her patron had taken him aside and put a hand on his shoulder and told him he wouldn’t be able to continue in his role as houseboy after his maman passed, but not to worry, le patron would make suitable arrangements with Alex’s father. Instead he told her menial details about his work around the house and about a little dead deer he’d seen while walking in the woods and all the insects crawling chaotically throughout its guts, which had been torn free of its body, probably by wolves. His maman was tiny and frail beneath a white sheet and she seldom acknowledged him with more than a moan, until one evening she was lucid and she sat up against the headboard and told him about his brother, his ’tit frère, who was born with a full head of black hair and never cried once because he was strong and powerful and brave, but quickly it was noticed that he struggled to breathe and frequently coughed up a pink foam, and after just a few days he died, perhaps from a buildup of fluid in his lungs. Alex was born a year later and they named him after his brother and this time the strength prevailed.

He’d told Serge that story back in Montréal and Serge had held him close and said he felt the power too. Now he’d have to use his puissance to haul Serge into the woods. First he’d roll him onto the bearskin and then he’d drag him over to the fire, and this he did despite a bark of pain from Serge, who came out of his stupor once Alex had moved their belongings into the trees.

Alex wrapped the bearskin around Serge’s enormous shoulders and threw more wood on the fire and offered Serge a piece of pemmican, but Serge couldn’t swallow because of the pain in his throat. He tried nevertheless, and the effort led to an explosive fit of coughing and both men heard the weak fire sizzle and silently they recognized this as the flames devouring whatever drops of blood had flown from Serge’s lungs then mouth.

It began to rain, at first lightly but soon much harder, and neither the deerskin tent nor the company blankets had made it off the boats.

‘Serre-moi fort,’ said Serge, so Alex put his arms around him and held him in his lap as the rain quickly extinguished the fire, and although they had their rum, Serge couldn’t imbibe but encouraged Alex, who drank despairingly as his friend began to sob.

The rain plastered Serge’s hair to his face and his beard to his neck and he shook with the force of his tears. Alex wanted to stroke his cheek but both sides of his friend’s face were scabby and swollen, so instead he just squeezed one of Serge’s hands. ‘T’inquiète pas, Serge. On gagne toujours, tu t’souviens-tu? Tout l’temps on gagne.’

Serge nodded but didn’t otherwise respond, and it seemed as though they were the only living creatures in an endless forest of dead brown needles.

Serge left before M. Anderson returned to the grocery store in the morning, and all throughout the day Alex struggled to conceal an inner glow that must’ve been happiness and maybe even joy. Serge came back that night and this time sat on the mattress beside Alex and told stories about his life, and when he offered his rum, Alex took a sip and winced but continued to drink whenever the bottle was passed. In return he gave Serge a few pieces of his bread, though he’d already eaten the rest of his meal.

Serge grinned and said his great-grandmother had been one of les filles du roi sent to New France by the Sun King and therefore his blood was nearly royal but his life experience was not. He’d grown up in Montréal a generation after the British took control and had known nothing but hardship and labour. He’d watched his mother die of cholera and his father like his grandfather was a coureur de bois, one of the remaining few who set out for Athabasca not long after his mother’s death, but the man never came home and there were no reports of his demise, only rumours that he’d chosen to live with the Cree or the Dene, no one knew which.

When Serge was twenty he decided to quit his job working the port and go find his father. He spoke of adventures both wonderful and wild, such as a bear that attacked his group and killed their leader and the men wandered off course in the wilderness and many died before they met a group of Indiens and traded their tin cups and tobacco pipes for guidance, but these men had never heard of his father and could speak very little French besides.

‘Weren’t you scared?’ Alex felt himself crude and sheltered but was nevertheless filled with pride that Serge chose to spend time in the back of the store when clearly he was a man who could avail himself of other options.

Serge smiled and shook his head, non, non, but then he sighed and sipped his rum and said, ‘Franchement, it was the storms that scared me from time to time, because the lightning once struck the trees and the whole forest turned to fire and in the flames I saw the Devil, but it seemed he didn’t see me himself, or if he did he wasn’t ready to take me, grâce à dieu.’

It was windy outside but not overcast and there was the faint light of the moon that found its way into the alley and through the dirty window. Alex shivered at the thought of the forest aflame and Serge stretched his arm around the boy’s shoulders and held him close and continued his story.

He spoke fondly of les Indiens and said over the course of many years he learned to speak Cree and Dene and some of the northern Iroquois spoken by the Huron, and after a deep pull from his bottle Serge remarked on the strength of these last people in particular, because although greatly reduced by disease and war, like the beaver they still survived and would persist even thereafter, and who could not respect such focus and fortitude? Serge said Indian languages were crucial in his development as coureur and to prove it he issued a series of strange sounds that Alex had not previously known possible, and he tried not to laugh but failed.

‘C’t’amusant, j’l’sais,’ slurred Serge, and he grinned and his teeth were yellow and one of his incisors completely brown. ‘But I’m telling you, my good friend, these men and women of the land opened my eyes to the biggest secret of my life.’

‘They helped you find your father?’ Alex heard the squeal of excitement in his voice and realized the rum had taken hold, but Serge was quiet and only drank from his bottle and shook his head, then drank again and passed the rum to Alex.

‘Non,’ he said after a pause. ‘I never found my father and to tell the truth I forgot what he looked like by the time I saw the Devil, and afterward I could never remember again.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Alex and he took Serge’s rough and hairy hand and held it but didn’t tell him about his own father, not right then, it felt wrong to commandeer the conversation, and the two of them held hands while Serge collected himself and returned to the topic of the secret revealed to him by les Indiens.

‘I stayed with them in their villages,’ he said. ‘We coureurs got on very well with them, better than most of these voyageurs you see now that things are organized. We respected them and they respected us and there was much trading not just of goods but also knowledge.’

Alex gave Serge’s hand a squeeze. ‘What did they teach you? What?’

Serge looked down at Alex and lifted the boy’s hand to his chest, and he chuckled and said, ‘They said I’m berdache, but slightly different, because I don’t concern myself with the work of a woman and nor am I the youngest in my affairs of love.’ He gave Alex an affirmative nod. ‘I’m slightly different.’

Alex didn’t understand and said so even as he began to feel tired and woozy, and Serge released his hand and patted his knee. ‘I think we’ve talked enough for tonight, my friend, don’t you? Let’s go to sleep now and talk more tomorrow, yes?’

Alex nodded and lay on his side and Serge blew out the candle and stretched out on the little strip of mattress, and just before Alex fell asleep he felt Serge’s arm encircle his chest and pull him close, and that was a feeling of warmth and safety.

Serge whispered in Alex’s ear. ‘You are very soft, Ali.’

Alex smiled in the dark.

Serge said, ‘You know, in the trade, it’s the soft beaver we like best.’

‘Why?’

‘It feels nice against the skin, very soft, and therefore people want it most.’

It rained all throughout the afternoon and into the evening, and for a while Alex sensed the presence of the sun behind the blackness of the clouds, but then it vanished and the two of them were lost in the wet and roaring darkness that was sometimes shattered by bolts of jagged blue lightning dancing across the summit of the cliff. In his right hand Alex clutched the rum and with chattering teeth he prayed to le seigneur that they’d be spared the flaming forest of Serge’s past. When he felt around with his left hand he was dismayed because Serge was mostly still, just the occasional and almost imperceptible rise of his wide chest.

Alex cried out but was unable to hear himself over the howl of the wind and the fury of the rain, and he didn’t want to but nevertheless and despite the treachery began to regret their ambition. Even if he’d been able to change the course of events he’d not have removed Serge from his life, non, jamais, but he would’ve steered them toward a different fate, and why not France, to find Alex’s father instead? But he’d suggested this and Serge had promised they’d indeed board a sail-ship, or maybe even a steamship, who knew, and together they’d make the journey, but first they needed money. They had to take advantage of what was surely the final era of fur trading brought about by the forced merger of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company after those two organizations had spilled each other’s blood throughout the great eastern forest and all the way across the northern plains as well. When Alex said he didn’t understand these details, Serge raised his finger and said he had only to understand that it was necessary for him to finally shed the old ways of the independent coureur, good and just for hundreds of years but no more, and they’d become not only licensed voyageurs but two among the hardiest hivernants who travelled from Lake Superior and into the rugged north, all the way to Lake Athabasca and the western height of Rupert’s Land, where the best furs could still be found in huge abundance and despite all the obscure machinations of business and the bloody friction between global powers, money could still be made, money they’d need if they were ever to travel to France to find Alex’s father. It was necessary, said Serge, for a man to be controlled before he could be free. That was just the miserable way of a miserable world.

This wisdom rang true and Alex was filled with further confidence when he learned of Serge’s prowess in the trade: the man could carry over two hundred pounds on his back with a tumpline cutting into the flesh of his forehead, he’d survived the musket blasts of rival trappers, he’d twice killed a bear with a single shot from a stolen firearm, and he’d beaten six men at once in a tavern fight in Grand Portage before the American border tariffs were enforced, after which he beat five more in Fort William. Serge said his reputation was fearsome and known throughout the trade, and within its culture and along its waterways he and Alex would be respected, not like in Montréal, where they were battered animals sneaking friendship in the shadows of maudit streets overrun by Protestants and Englishmen and all manner of pute and con and diable.

But now look at them, thought Alex, his eyes full of tears. Now look at their situation: ruined. What furs they had were too drenched for comfort and too tattered to trade, even if such an option were possible. As for food, the biscuits had probably dissolved in the deluge, but Alex thought he might find the pemmican and beans, even in the darkness, and he swigged from his rum and came across the axe instead. He held it in his left hand and like the rum wouldn’t let go lest Serge’s devils burst out of the storm and drag them away.

‘Buggery!’ bellowed M. Anderson, holding open the door to the back room with the palm of one hand and making a fist of the other. Alex wasn’t quite awake when he heard this but knew he wasn’t dreaming, just as he knew the pain in his head and the dryness in his bones were the work of the rum, though it had left behind an oily film of pleasure as well. He was still cupped against Serge’s body, the stout giant’s arm across his chest like a plate of armour, and he felt himself shielded by strength as Serge vaulted shirtless off the mattress and squared his hairy shoulders at le patron. This happened quickly and Alex hadn’t yet sat up and it was clear M. Anderson also didn’t expect resistance or outburst, not because he’d thought about the matter but because his instincts had always told him such things weren’t his concern, and so his expression was almost comical in its nudity of first-born shock and fear. M. Anderson’s knees gave out and his mouth hung open, so strange and feeble when not gathered and pressed around the tip of his pipe. Serge was too principled to harm a man so frightened, but Alex knew that if violence had come to pass, the question of the victor would’ve been no question at all, and afterward they would’ve burned down the store and felt no remorse, rather left M. Anderson to crawl back to his father’s estate, battered and reduced. But it didn’t come to that, for Serge merely slammed the door in le patron’s face. Then he turned and with a smile he said, ‘Emmène tes affaires.’

And so they spent the end of the summer and the whole of the winter living together in a hotel by the port, and these days and nights were unlike any Alex had known. Their room was simple and modest, comprised of a small bed and a night table, a candle and a chamber pot, and it had a window that looked down onto the street, which at first was muddy, and then, as the months passed, snowy. During the days, Serge toured the taverns playing cards and mostly winning and with the proceeds he paid for the room and fed them both. At night, he returned with rum and meat and cheese and sometimes even wine. They stayed up late, holding each other in bed, and in the safety of their candlelit cocoon Alex told Serge about his maman and his papa and the ’tit frère he’d never met. After the story of his maman’s passing, Serge gathered Alex’s face in his brutish hands and kissed the boy as tenderly as his coarse lips would allow, and he said, ‘C’est trop dure, mon cher Ali, bien trop dure.’

Alex began to cry and Serge led him from the bed to the window. They surveyed the filthy snowdrifts below and the huddled people walking between them and a bright red sleigh pulled merrily by a team of horses, and he told Alex that in the spring they’d leave this city behind. He’d met an Englishman in the taverns who recruited people on behalf of the fur company, and it didn’t matter that this man didn’t like Serge, because he couldn’t beat him in cards, no matter how often they played, and his pride led them to play often.

All of life, said Serge, was a sequence of random opportunities and it was the task of every man to await the arrival of his own, even if later he convinced himself and others he’d been the one to contrive the circumstances in a howling absence of luck and good fortune. In time Serge would be able to turn the recruiter’s debt into a service, and that service would be two positions on one of the voyageur brigades that would set out from Lachine in spring, and although most men found the work both difficult and dangerous, for them it would be otherwise because the Englishman would guarantee special treatment for the few months it took to reach Fort William, whence they’d join up with another brigade and work their way north, and here Serge wouldn’t have to rely on guile to be recruited because the northbound brigades suffered many losses due to hernias and drownings and starvation, so positions on les canots were always available.

‘After that, the work will get harder,’ said Serge, ‘much harder. But you’ll be stronger and more capable, and together we’ll head north to make our fortune.’

‘And then,’ sniffed Alex, ‘will we go back to Montréal and continue to France?’

Serge returned to the bed and plucked a hunk of meat from the nightstand. He popped it into his mouth and opened his arms and beckoned for Alex to join him, and when the boy was again in his arms Serge promised they’d set out for Paris as soon as they were ready, and by that time Alex would be a powerful man the likes of which would inspire pride in his papa and everyone else besides.

Giddy with this vision, Alex drew pictures during the day but not just with scraps of wood and lumps of coal; rather Serge through cards had won him three sheets of paper made from rags in Argenteuil, Québec, as well as pencils imported from France. On the sheets he sketched a rough portrait of Serge sleeping in bed with the covers bundled at his waist and another of Serge with his hair obscuring his face and another of Serge selecting an apple from the displays outside M. Anderson’s store. When he went back to the wood and coal and looked at the ceiling and closed his eyes and moved his hands rapidly and at random as he’d done so many times before, the results were different, the whorls and swirls were joyous, the smears and smudges ecstatic, and Serge had a carpenter attach a length of wire to the back of one of these efforts, and with a delighted smile he hung it from a nail in the wall over their bed.

In February, Alex was sitting beneath it and working on a portrait, and the sun had gone down and Serge had yet to return when there was a knock at the door. Alex imagined his friend on the other side, arms too full of rum and sausage to manage the handle himself, so he climbed out of bed and opened the door, but it wasn’t Serge who stood there, rather a tall and clean-shaven man with a tiny mouth who spoke English in an accent too thick for Alex to comprehend, and this confusion turned to horror when the man threw his fist into Alex’s face.

Alex fell to the ground and felt one of his elbows thump the floor and go numb. He’d been beaten before, not just by M. Anderson but also countless times by the sons of his maman’s patron, and he knew that understanding why wasn’t as important as protecting his head and ribs, so he curled fetal as the man set about kicking him across the floor and under the bed, after which he opened his eyes but only to see the bed lift off the ground and fly into the wall, this because his assailant had thrown it there and kicked him in the mouth and called him a sodomite and kicked him in both forearms as Alex once more managed to cover his face.

The kicking seemed as interminable as the winter until Alex heard the familiar sounds of Serge grunting and swearing, and when he lowered his arms he saw his friend toss the assailant into the wall and then grab him by the hair and slam his face into the wood panels until a bloodstain appeared and gradually expanded and droplets broke free and trickled to the floor.

After half a dozen of these blows or more, Serge released the man’s hair and the man crumpled to his knees and fell backwards, his face a pool of furrowed flesh and shining blood. Serge took him by the wrists, spun him around, and dragged him into the hall, then closed the door and rushed over to Alex and collected him in his arms. Alex was nearly unconscious but terror kept his senses alive and so he heard the commotion in the hall and the pounding of fists on the door, but the noise broke off when Serge bellowed that it must, and Alex wouldn’t remember what happened until a few days later when he awoke in bed and Serge was at his side and explained that a man he’d bested in cards had tracked them down but no one would ever be so foolish as to attempt such an assault again.

‘There’ll be people who see that we’re strong and try to take it,’ said Serge. ‘But we’ll never let them.’

Alex tried to smile but his face was swollen and the pain was intense and Serge reached below the sheets and coaxed from his body the special sensation he’d come to love.

‘J’ai d’bonnes nouvelles,’ said Serge after the sensation had subsided and the wet had been dried. ‘We leave with a brigade as soon as the ice breaks on the rivers. It’ll be exactly as I promised.’

Alex awoke beneath the trees still holding the axe but not the bottle because he’d drunk all the rum during the storm. It was morning and the sun was shining and his face and neck were coated with blackflies. Booze had scraped out his skull many times in the past ten months, but this time it hadn’t left any lingering quality of joy, and he knew before turning over that Serge was dead, so he stayed as he was for a while, letting the tears stream out of his eyes. When he did roll over and look at his best friend slumped against a tree in front of the sodden firepit, he saw that hordes of flies were eating the smashed pulp of Serge’s face and only the man’s broken nose emerged from this melee, but crooked and sad. Alex crawled over and laid himself across Serge’s stiff and wet and lifeless lap and tried again to sleep but couldn’t and thought he might never manage anything like sleep again. He lay there until the sun crept across the sky and night fell once again over the river and its forests and cliffs, and in that inky darkness he sketched with his mind an outcome more like the one they’d intended: the two of them aboard a steamship as it left the St. Lawrence and entered the Atlantic, bound for Paris and the new life there promised.

2

Serge’s body was too heavy to carry or drag, and come the next morning Alex understood he’d have to abandon his friend to the insects and animals. The sky was cloudy and he went to the river and looked across at the stark grey face of the looming cliff and kneeled in the weeds and drank from the water until his belly sloshed. He set about gathering what supplies were left scattered about the beach and the edge of the forest. He’d been grief-stricken before and now he was again and this was surely the will of le seigneur, and perhaps like his papa he was too afraid to complain lest he summon from Heaven yet another bolt of anguish and loss.

He was careful not to look at Serge as he went about his task but couldn’t ignore the frantic buzzing of a thousand flies. He had a kettle, but there was no wood dry enough to make a fire, so he swallowed a handful of raw beans that went down like pebbles. Then he found some pemmican and chewed it while rooting through Serge’s deerskin bag, which he discovered half-buried in the mud. The portraits he’d made were rolled up inside, but the rain had ruined them and he’d have to work hard to never forget the way Serge had looked in Montréal.

After an hour he was ready to leave. He sobbed and swayed and slung Serge’s bag over his shoulder and took up the axe in his right hand and walked in the direction the brigade had gone two days before. The shore was rocky and the river glassy and the forest still. He felt flushed with shame because he recognized in himself a longing not just for Serge but also the men of the brigade and even M. Anderson, because truly he was lost and these men might’ve helped him no matter the coarseness of their hearts.

He walked for half a day and still felt strong and that worried him. It didn’t make sense that the river was so calm after such a downpour, and why wasn’t he sick after spending so much time so close to Serge? Maybe the Devil had crawled out of the storm and claimed his soul while he slept drunkenly in the mud. His unease worsened as time went on and the dull grey light of day lessened not at all.