5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

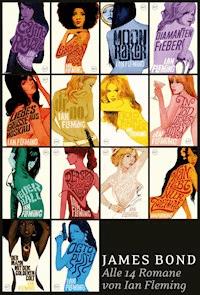

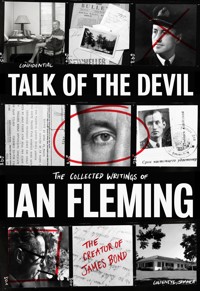

- Herausgeber: Ian Fleming Publications

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: James Bond 007

- Sprache: Englisch

Meet James Bond, the world's most famous spy.Upon M's insistence, James Bond takes a two-week respite in a secluded natural health spa. But amid the bland teas, tasteless yogurts, and the spine stretcher the guests lovingly call "The Rack," Bond stumbles onto the trail of a lethal man with ties to a new secret organisation called SPECTRE. When SPECTRE hijacks two A-bombs, a frantic global search for the weapons ensues, and M's hunch that the plane containing the bombs will make a clean drop into the ocean sends Bond to the Bahamas to investigate.On the island paradise, 007 finds a wealthy pleasure seeker's treasure hunt and meets Domino Vitali, the gorgeous mistress of Emilio Largo, otherwise known as SPECTRE's Number 1. But as powerful as Number 1 is, he works for someone else: Ernst Stavro Blofeld, a peculiar man with a deadly creative mind.The ninth novel in Ian Fleming's James Bond series, Thunderball marks the beginnings of one of the most iconic villains in history, and the only match for the wits of James Bond.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 425

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Thunderball

Thunderball

IAN FLEMING

ToErnest Cuneomuse

Contents

1: Take It Easy, Mr Bond

2: Shrublands

3: The Rack

4: Tea and Animosity

5: Spectre

6: Violet-Scented Breath

7: Fasten Your Lap-Strap

8: Big Fleas Have Little Fleas . . .

9: Multiple Requiem

10: The Disco Volante

11: Domino

12: The Man from the CIA

13: My Name Is Emilio Largo

14: Sour Martinis

15: Cardboard Hero

16: Swimming the Gauntlet

17: The Red-Eyed Catacomb

18: How To Eat a Girl

19: When the Kissing Stopped

20: Time for Decision

21: Very Softly, Very Slowly

22: The Shadower

23: Naked Warfare

24: Take It Easy, Mr Bond

1

Take It Easy, Mr Bond

It was one of those days when it seemed to James Bond that all life, as someone put it, was nothing but a heap of six to four against.

To begin with he was ashamed of himself – a rare state of mind. He had a hangover, a bad one, with an aching head and stiff joints. When he coughed – smoking too much goes with drinking too much and doubles the hangover – a cloud of small luminous black spots swam across his vision like amoebae in pond water. The ‘one drink too many’ signals itself unmistakably. His final whisky and soda in the luxurious flat in Park Lane had been no different from the ten preceding ones, but it had gone down reluctantly and had left a bitter taste and an ugly sensation of surfeit. And, although he had taken in the message, he had agreed to play just one more rubber. Five pounds a hundred as it’s the last one? He had agreed. And he had played the rubber like a fool. Even now he could see the queen of spades, with that stupid Mona Lisa smile on her fat face, slapping triumphantly down on his knave – the queen, as his partner had so sharply reminded him, that had been so infallibly marked with South, and that had made the difference between a grand slam redoubled (drunkenly) for him, and four hundred points above the line for the opposition. In the end it had been a twenty-point rubber, £100 against him – important money.

Again Bond dabbed with the bloodstained styptic pencil at the cut on his chin and despised the face that stared sullenly back at him from the mirror above the washbasin. Stupid, ignorant bastard! It all came from having nothing to do. More than a month of paperwork – ticking off his number on stupid dockets, scribbling minutes that got spikier as the weeks passed, and snapping back down the telephone when some harmless section officer tried to argue with him. And then his secretary had gone down with the flu and he had been given a silly, and, worse, ugly bitch from the pool who called him ‘sir’ and spoke to him primly through a mouth full of fruit stones. And now it was another Monday morning. Another week was beginning. The May rain thrashed at the windows. Bond swallowed down two Phensics and reached for the Enos. The telephone in his bedroom rang. It was the loud ring of the direct line with Headquarters.

James Bond, his heart thumping faster than it should have done, despite the race across London and a fretful wait for the lift to the eighth floor, pulled out the chair and sat down and looked across into the calm, grey, damnably clear eyes he knew so well. What could he read in them?

‘Good morning, James. Sorry to pull you along a bit early in the morning. Got a very full day ahead. Wanted to fit you in before the rush.’

Bond’s excitement waned minutely. It was never a good sign when M addressed him by his Christian name instead of by his number. This didn’t look like a job – more like something personal. There was none of the tension in M’s voice that heralded big, exciting news. M’s expression was interested, friendly, almost benign. Bond said something non-committal.

‘Haven’t seen much of you lately, James. How have you been? Your health, I mean.’ M picked up a sheet of paper, a form of some kind, from his desk, and held it as if preparing to read.

Suspiciously, trying to guess what the paper said, what all this was about, Bond said, ‘I’m all right, sir.’

M said mildly, ‘That’s not what the MO thinks, James. Just had your last Medical. I think you ought to hear what he has to say.’

Bond looked angrily at the back of the paper. Now what the hell! He said with control, ‘Just as you say, sir.’

M gave Bond a careful, appraising glance. He held the paper closer to his eyes. ‘“This officer,” he read, ‘“remains basically physically sound. Unfortunately his mode of life is not such as is likely to allow him to remain in this happy state. Despite many previous warnings, he admits to smoking sixty cigarettes a day. These are of a Balkan mixture with a higher nicotine content than the cheaper varieties. When not engaged upon strenuous duty, the officer’s average daily consumption of alcohol is in the region of half a bottle of spirits of between sixty and seventy proof. On examination, there continues to be little definite sign of deterioration. The tongue is furred. The blood pressure a little raised at 160/90. The liver is not palpable. On the other hand, when pressed, the officer admits to frequent occipital headaches and there is spasm in the trapezius muscles and so-called ‘fibrositis’ nodules can be felt. I believe these symptoms to be due to this officer’s mode of life. He is not responsive to the suggestion that over-indulgence is no remedy for the tensions inherent in his professional calling and can only result in the creation of a toxic state which could finally have the effect of reducing his fitness as an officer. I recommend that No. 007 should take it easy for two to three weeks on a more abstemious regime, when I believe he would make a complete return to his previous exceptionally high state of physical fitness.”’

M reached over and slid the report into his OUT tray. He put his hands flat down on the desk in front of him and looked sternly across at Bond. He said, ‘Not very satisfactory is it, James?’

Bond tried to keep impatience out of his voice. He said, ‘I’m perfectly fit, sir. Everyone has occasional headaches. Most weekend golfers have fibrositis. You get it from sweating and then sitting in a draught. Aspirin and embrocation get rid of them. Nothing to it really, sir.’

M said severely, ‘That’s just where you’re making a big mistake, James. Taking medicine only suppresses these symptoms of yours. Medicine doesn’t get to the root of the trouble. It only conceals it. The result is a more highly poisoned condition which may become chronic disease. All drugs are harmful to the system. They are contrary to nature. The same applies to most of the food we eat – white bread with all the roughage removed, refined sugar with all the goodness machined out of it, pasteurised milk which has had most of the vitamins boiled away, everything overcooked and denaturised. Why,’ M reached into his pocket for his notebook and consulted it, ‘do you know what our bread contains apart from a bit of overground flour?’ M looked accusingly at Bond. ‘It contains large quantities of chalk, also benzol peroxide powder, chlorine gas, sal ammoniac and alum.’ M put the notebook back in his pocket. ‘What do you think of that?’

Bond, mystified by all this, said defensively, ‘I don’t eat all that much bread, sir.’

‘Maybe not,’ said M impatiently. ‘But how much stoneground wholewheat do you eat? How much yoghurt? Uncooked vegetables, nuts, fresh fruit?’

Bond smiled. ‘Practically none at all, sir.’

‘It’s no laughing matter.’ M tapped his forefinger on the desk for emphasis. ‘Mark my words. There is no way to health except the natural way. All your troubles’ – Bond opened his mouth to protest, but M held up his hand – ‘the deep-seated toxaemia revealed by your Medical, are the result of a basically unnatural way of life. Ever heard of Bircher-Brenner, for instance? Or Kneipp, Preissnitz, Rikli, Schroth, Gossman, Bilz?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Just so. Well those are the men you would be wise to study. Those are the great naturopaths – the men whose teaching we have foolishly ignored. Fortunately,’ M’s eyes gleamed enthusiastically, ‘there are a number of disciples of these men practising in England. Nature cure is not beyond our reach.’

James Bond looked curiously at M. What the hell had got into the old man? Was all this the first sign of senile decay? But M looked fitter than Bond had ever seen him. The cold grey eyes were clear as crystal and the skin of the hard, lined face was luminous with health. Even the iron-grey hair seemed to have new life. Then what was all this lunacy?

M reached for his IN tray and placed it in front of him in a preliminary gesture of dismissal. He said cheerfully, ‘Well, that’s all, James. Miss Moneypenny has made the reservation. Two weeks will be quite enough to put you right. You won’t know yourself when you come out. New man.’

Bond looked across at M, aghast. He said in a strangled voice, ‘Out of where, sir?’

‘Place called “Shrublands”. Run by quite a famous man in his line – Wain, Joshua Wain. Remarkable chap. Sixty-five. Doesn’t look a day over forty. He’ll take good care of you. Very up-to-date equipment, and he’s even got his own herb garden. Nice stretch of country. Near Washington in Sussex. And don’t worry about your work here. Put it right out of your mind for a couple of weeks. I’ll tell 009 to take care of the Section.’

Bond couldn’t believe his ears. He said, ‘But, sir. I mean, I’m perfectly all right. Are you sure? I mean, is this really necessary?’

‘No,’ M smiled frostily. ‘Not necessary. Essential. If you want to stay in the Double O Section, that is. I can’t afford to have an officer in that section who isn’t one hundred per cent fit.’ M lowered his eyes to the basket in front of him and took out a signal file. ‘That’s all, 007.’ He didn’t look up. The tone of voice was final.

Bond got to his feet. He said nothing. He walked across the room and let himself out, closing the door with exaggerated softness.

Outside the door, Miss Moneypenny looked sweetly up at him.

Bond walked over to her desk and banged his fist down so that the typewriter jumped. He said furiously, ‘Now what the hell, Penny? Has the old man gone off his rocker? What’s all this bloody nonsense? I’m damned if I’m going. He’s absolutely nuts.’

Miss Moneypenny smiled happily. ‘The manager’s been terribly helpful and kind. He says he can give you the Myrtle room, in the Annex. He says it’s a lovely room. It looks right over the herb garden. They’ve got their own herb garden, you know.’

‘I know all about their bloody herb garden. Now look here, Penny,’ Bond pleaded with her, ‘be a good girl and tell me what it’s all about. What’s eating him?’

Miss Moneypenny, who often dreamt hopelessly about Bond, took pity on him. She lowered her voice conspiratorially. ‘As a matter of fact, I think it’s only a passing phase. But it is rather bad luck on you getting caught up in it before it’s passed. You know he’s always apt to get bees in his bonnet about the efficiency of the Service. There was the time when all of us had to go through that physical exercise course. Then he had that headshrinker in, the psychoanalyst man – you missed that. You were somewhere abroad. All the Heads of Section had to tell him their dreams. He didn’t last long. Some of their dreams must have scared him off or something. Well, last month M got lumbago and some friend of his at Blades, one of the fat, drinking ones I suppose,’ Miss Moneypenny turned down her desirable mouth, ‘told him about this place in the country. This man swore by it. Told M that we were all like motor cars and that all we needed from time to time was to go to a garage and get decarbonised. He said he went there every year. He said it only cost twenty guineas a week which was less than what he spent in Blades in one day and it made him feel wonderful. Well, you know M always likes trying new things, and he went there for ten days and came back absolutely sold on the place. Yesterday he gave me a great talking-to all about it and this morning in the post I got a whole lot of tins of treacle and wheatgerm and heaven knows what all. I don’t know what to do with the stuff. I’m afraid my poor poodle’ll have to live on it. Anyway, that’s what happened and I must say I’ve never seen him in such wonderful form. He’s absolutely rejuvenated.’

‘He looks like that blasted man in the old Kruschen Salts advertisements. But why does he pick on me to go to this nuthouse?’

Miss Moneypenny gave a secret smile. ‘You know he thinks the world of you – or perhaps you don’t. Anyway, as soon as he saw your Medical he told me to book you in.’ Miss Moneypenny screwed up her nose. ‘But, James, do you really drink and smoke as much as that? It can’t be good for you, you know.’ She looked up at him with motherly eyes.

Bond controlled himself. He summoned a desperate effort at nonchalance, at the throwaway phrase. ‘It’s just that I’d rather die of drink than of thirst. As for the cigarettes, it’s really only that I don’t know what to do with my hands.’ He heard the stale, hangover words fall like clinker in a dead grate. Cut out the schmaltz! What you need is a double brandy and soda.

Miss Moneypenny’s warm lips pursed into a disapproving line. ‘About the hands – that’s not what I’ve heard.’

‘Now don’t you start on me, Penny.’ Bond walked angrily towards the door. He turned round. ‘Any more ticking-off from you and when I get out of this place I’ll give you such a spanking you’ll have to do your typing off a block of Dunlopillo.’

Miss Moneypenny smiled sweetly at him. ‘I don’t think you’ll be able to do much spanking after living on nuts and lemon juice for two weeks, James.’

Bond made a noise between a grunt and a snarl and stormed out of the room.

2

Shrublands

James Bond slung his suitcase into the back of the old chocolate-brown Austin taxi and climbed into the front seat beside the foxy, pimpled young man in the black leather windcheater. The young man took a comb out of his breast pocket, ran it carefully through both sides of his ducktail haircut, put the comb back in his pocket, then leant forward and pressed the self-starter. The play with the comb, Bond guessed, was to assert to Bond that the driver was really only taking him and his money as a favour. It was typical of the cheap self-assertiveness of young labour since the war. This youth, thought Bond, makes about twenty pounds a week, despises his parents, and would like to be Tommy Steele. It’s not his fault. He was born into the buyers’ market of the Welfare State and into the age of atomic bombs and space flight. For him life is easy and meaningless. Bond said, ‘How far is it to “Shrublands”?’

The young man did an expert but unnecessary racing change round an island and changed up again. ‘’Bout half an hour.’ He put his foot down on the accelerator and neatly but rather dangerously overtook a lorry at an intersection.

‘You certainly get the most out of your Bluebird.’

The young man glanced sideways to see if he was being laughed at. He decided that he wasn’t. He unbent fractionally. ‘My dad won’t spring me something better. Says this old crate was okay for him for twenty years so it’s got to be okay for me for another twenty. So I’m putting money by on my own. Halfway there already.’

Bond decided that the comb-play had made him over-censorious. He said, ‘What are you going to get?’

‘Volkswagen Minibus. Do the Brighton races.’

‘That sounds a good idea. Plenty of money in Brighton.’

‘I’ll say.’ The young man showed a trace of enthusiasm. ‘Only time I ever got there, a couple of bookies had me take them and a couple of tarts to London. Ten quid and a fiver tip. Piece of cake.’

‘Certainly was. But you can get both kinds at Brighton. You want to watch out for being mugged and rolled. There are some tough gangs operating out of Brighton. What’s happened to the Bucket of Blood these days?’

‘Never opened up again after that case they had. The one that got in all the papers.’ The young man realised that he was talking as if to an equal. He glanced sideways and looked Bond up and down with a new interest. ‘You going into the Scrubs or just visiting?’

‘Scrubs?’

‘Shrublands – Wormwood Scrubs – Scrubs,’ said the young man laconically. ‘You’re not like the usual ones I get to take there. Mostly fat women and old geezers who tell me not to drive so fast or it’ll shake up their sciatica or something.’

Bond laughed. ‘I’ve got fourteen days without the option. Doctor thinks it’ll do me good. Got to take it easy. What do they think of the place round here?’

The young man took the turning off the Brighton road and drove westwards under the Downs through Poynings and Fulking. The Austin whined stolidly through the inoffensive countryside. ‘People think they’re a lot of crackpots. Don’t care for the place. All those rich folk and they don’t spend any money in the area. Tea-rooms make a bit out of them – specially out of the cheats.’ He looked at Bond. ‘You’d be surprised. Grown people, some of them pretty big shots in the City and so forth, and they motor around in their Bentleys with their bellies empty and they see a tea-shop and go in just for their cups of tea. That’s all they’re allowed. Next thing, they see some guy eating buttered toast and sugar cakes at the next table and they can’t stand it. They order mounds of the stuff and hog it down just like kids who’ve broken into the larder – looking round all the time to see if they’ve been spotted. You’d think people like that would be ashamed of themselves.’

‘Seems a bit silly when they’re paying plenty to take the cure or whatever it is.’

‘And that’s another thing,’ the young man’s voice was indignant. ‘I can understand charging twenty quid a week and giving you three square meals a day, but how do they get away with charging twenty quid for giving you nothing but hot water to eat? Doesn’t make sense.’

‘I suppose there are the treatments. And it must be worth it to the people if they get well.’

‘Guess so,’ said the young man doubtfully. ‘Some of them do look a bit different when I come to take them back to the station.’ He sniggered. ‘And some of them change into real old goats after a week of nuts and so forth. Guess I might try it myself one day.’

‘What do you mean?’

The young man glanced at Bond. Reassured and remembering Bond’s worldly comments on Brighton, he said, ‘Well, you see we got a girl here in Washington. Racy bird. Sort of local tart if you see what I mean. Waitress at a place called the Honey Bee Tea-Shop – or was, rather. She started most of us off, if you get my meaning. Quid a go and she knows a lot of French tricks. Regular sport. Well, this year the word got round up at the Scrubs and some of these old goats began patronising Polly – Polly Grace, that’s her name. Took her out in their Bentleys and gave her a roll in a deserted quarry up on the Downs. That’s been her pitch for years. Trouble was they paid her five, ten quid and she soon got too good for the likes of us. Priced her out of our market, so to speak. Inflation, sort of. And a month ago she chucked up her job at the Honey Bee, and you know what?’ The young man’s voice was loud with indignation. ‘She bought herself a beat-up Austin Metropolitan for a couple of hundred quid and went mobile. Just like the London tarts in Curzon Street they talk about in the papers. Now she’s off to Brighton, Lewes – anywhere she can find the sports, and in between whiles she goes to work in the quarry with these old goats from the Scrubs! Would you believe it!’ The young man gave an angry blast on his klaxon at an inoffensive couple on a tandem bicycle.

Bond said seriously, ‘That’s too bad. I wouldn’t have thought these people would be interested in that sort of thing on nut cutlets and dandelion wine or whatever they get to eat at this place.’

The young man snorted. ‘That’s all you know. I mean’ – he felt he had been too emphatic – ‘that’s what we all thought. One of my pals, he’s the son of the local doctor, talked the thing over with his dad – in a roundabout way, sort of. And his dad said no. He said that this sort of diet and no drink and plenty of rest, what with the massage and the hot and cold Sitz baths and what have you, he said that all clears the bloodstream and tones up the system, if you get my meaning. Wakes the old goats up – makes ’em want to start cutting the mustard again, if you know the song by that Rosemary Clooney.’

Bond laughed. He said, ‘Well, well. Perhaps there’s something to the place after all.’

A sign on the right of the road said ‘“Shrublands”. Gateway to Health. First right. Silence please.’ The road ran through a wide belt of firs and evergreens in a fold of the Downs. A high wall appeared and then an imposing, mock-battlemented entrance with a Victorian lodge from which a thin wisp of smoke rose straight up among the quiet trees. The young man turned in and followed a gravel sweep between thick laurel bushes. An elderly couple cringed off the drive at a blare from his klaxon and then on the right there were broad stretches of lawn and neatly flowered borders and a sprinkling of slowly moving figures, alone and in pairs, and behind them a red brick Victorian monstrosity from which a long glass sun-parlour extended to the edge of the grass.

The young man pulled up beneath a heavy portico with a crenellated roof. Beside a varnished, iron-studded arched door stood a tall glazed urn above which a notice said: ‘No smoking inside. Cigarettes here please.’ Bond got down from the taxi and pulled his suitcase out of the back. He gave the young man a ten-shilling tip. The young man accepted it as no less than his due. He said, ‘Thanks. You ever want to break out, you can call me up. Polly’s not the only one. And there’s a teashop on the Brighton road has buttered muffins. So long.’ He banged the gears into bottom and ground off back the way he had come. Bond picked up his suitcase and walked resignedly up the steps and through the heavy door.

Inside it was very warm and quiet. At the reception desk in the big oak-panelled hall a severely pretty girl in starched white welcomed him briskly. When he had signed the register she led him through a series of sombrely furnished public rooms and down a neutral-smelling white corridor to the back of the building. Here there was a communicating door with the annex, a long low cheaply built structure with rooms on both sides of a central passage. The doors bore the names of flowers and shrubs. She showed him into Myrtle, told him that ‘the Chief’ would see him in an hour’s time, at six o’clock, and left him.

It was a room-shaped room with furniture-shaped furniture, and dainty curtains. The bed was provided with an electric blanket. There was a vase containing three marigolds beside the bed and a book called Nature Cure Explained by Alan Moyle, MBNA. Bond opened it and ascertained that the initials stood for ‘Member: British Naturopathic Association’. He turned off the central heating and opened the windows wide. The herb garden, row upon row of small nameless plants round a central sundial, smiled up at him. Bond unpacked his things and sat down in the single armchair and read about eliminating the waste products from his body. He learnt a great deal about foods he had never heard of, such as potassium broth, nut mince, and the mysteriously named unmalted slippery elm. He had got as far as the chapter on massage and was reflecting on the injunction that this art should be divided into Effleurage, Stroking, Friction, Kneading, Petrissage, Tapotement and Vibration, when the telephone rang. A girl’s voice said that Mr Wain would be glad to see him in Consulting Room A in five minutes.

Mr Joshua Wain had a firm, dry handshake and a resonant, encouraging voice. He had a lot of bushy grey hair above an unlined brow, soft, clear brown eyes, and a sincere and Christian smile. He appeared to be genuinely pleased to see Bond and to be interested in him. He wore a very clean smock-like coat with short sleeves from which strong hairy arms hung relaxed. Below were rather incongruous pinstripe trousers. He wore sandals over socks of conservative grey and when he moved across the consulting-room his stride was a springy lope.

Mr Wain asked Bond to remove all his clothes except his pants. When he saw the many scars he said politely, ‘Dear me, you do seem to have been in the wars, Mr Bond.’

Bond said indifferently, ‘Near miss. During the war.’

‘Really! War between peoples is a terrible thing. Now, just breathe in deeply, please.’ Mr Wain listened at Bond’s back and chest, took his blood pressure, weighed him and recorded his height, and then, after asking him to lie face down on a surgical couch, handled his joints and vertebrae with soft, probing fingers.

While Bond replaced his clothes, Mr Wain wrote busily at his desk. Then he sat back. ‘Well, Mr Bond, nothing much to worry about here, I think. Blood pressure a little high, slight osteopathic lesions in the upper vertebrae – they’ll probably be causing your tension headaches, by the way – and some right sacroiliac strain with the right ilium slightly displaced backwards. Due to a bad fall some time, no doubt.’ Mr Wain raised his eyes for confirmation.

Bond said, ‘Perhaps.’ Inwardly he reflected that the ‘bad fall’ had probably been when he had had to jump from the Arlberg Express after Heinkel and his friends had caught up with him around the time of the Hungarian uprising in 1956.

‘Well now.’ Mr Wain drew a printed form towards him and thoughtfully ticked off items on a list. ‘Strict dieting for one week to eliminate the toxins in the bloodstream. Massage to tone you up, irrigation, hot and cold Sitz baths, osteopathic treatment and a short course of Traction to get rid of the lesions. That should put you right. And complete rest, of course. Just take it easy, Mr Bond. You’re a civil servant, I understand. Do you good to get away from all that worrying paperwork for a while.’ Mr Wain got up and handed the printed form to Bond. ‘Treatment-rooms in half an hour, Mr Bond. No harm in starting right away.’

‘Thank you.’ Bond took the form and glanced at it. ‘What’s Traction, by the way?’

‘A medical device for stretching the spine. Very beneficial.’ Mr Wain smiled indulgently. ‘Don’t be worried by what some of the other patients tell you about it. They call it “The Rack”. You know what wags some people are.’

‘Yes.’

Bond walked out and along the white painted corridor. People were sitting about, reading or talking in soft tones in the public rooms. They were all elderly, middle-class people, mostly women, many of whom wore unattractive quilted dressing-gowns. The warm, close air and the frumpish women gave Bond claustrophobia. He walked through the hall to the main door and let himself out into the wonderful fresh air.

Bond walked thoughtfully down the trim narrow drive and smelt the musty smell of the laurels and the laburnums. Could he stand it? Was there any way out of this hell-hole short of resigning from the Service? Deep in thought, he almost collided with a girl in white who came hurrying round a sharp bend in the thickly hedged drive. At the same instant as she swerved out of his path and flashed him an amused smile, a mauve Bentley, taking the corner too fast, was on top of her. At one moment she was almost under its wheels, at the next, Bond, with one swift step, had gathered her up by the waist and, executing a passable Veronica, with a sharp swivel of his hips had picked her body literally off the bonnet of the car. He put the girl down as the Bentley dry-skidded to a stop in the gravel. His right hand held the memory of one beautiful breast. The girl said ‘Oh!’ and looked up into his eyes with an expression of flurried astonishment. Then she took in what had happened and said breathlessly, ‘Oh, thank you.’ She turned towards the car. A man had climbed unhurriedly down from the driving seat. He said calmly, ‘I am so sorry. Are you all right?’ Recognition dawned on his face. He said silkily, ‘Why, if it isn’t my friend Patricia? How are you, Pat? All ready for me?’

The man was extremely handsome – a dark bronzed woman-killer with a neat moustache above the sort of callous mouth women kiss in their dreams. He had regular features that suggested Spanish or South American blood and bold, hard brown eyes that turned up oddly, or, as a woman would put it, intriguingly, at the corners. He was an athletic-looking six foot, dressed in the sort of casually well-cut beige herringbone tweed that suggests Anderson and Sheppard. He wore a white silk shirt and a dark red polka-dot tie, and the soft dark brown V-necked sweater looked like vicuña. Bond summed him up as a good-looking bastard who got all the women he wanted and probably lived on them – and lived well.

The girl had recovered her poise. She said severely, ‘You really ought to be more careful, Count Lippe. You know there are always patients and staff walking down this drive. If it hadn’t been for this gentleman,’ she smiled at Bond, ‘you’d have run me over. After all, there is a big sign asking drivers to take care.’

‘I am so sorry, my dear. I was hurrying. I am late for my appointment with the good Mr Wain. I am as usual in need of decarbonisation – this time after two weeks in Paris.’ He turned to Bond. He said with a hint of condescension, ‘Thank you, my dear sir. You have quick reactions. And now, if you will forgive me—’ He raised a hand, got back into the Bentley, and purred off up the drive.

The girl said, ‘Now I really must hurry. I’m terribly late.’ Together they turned and walked after the Bentley.

Bond said, examining her, ‘Do you work here?’ She said that she did. She had been at Shrublands for three years. She liked it. And how long was he staying? The small-talk continued.

She was an athletic-looking girl whom Bond would have casually associated with tennis, or skating, or showjumping. She had the sort of firm, compact figure that always attracted him and a fresh open-air type of prettiness that would have been commonplace but for a wide, rather passionate mouth and a hint of authority that would be a challenge to men. She was dressed in a feminine version of the white smock worn by Mr Wain, and it was clear from the undisguised curves of her breasts and hips that she had little on underneath it. Bond asked her if she didn’t get bored. What did she do with her time off?

She acknowledged the gambit with a smile and a quick glance of appraisal. ‘I’ve got one of those bubble cars. I get about the country quite a lot. And there are wonderful walks. And one’s always seeing new people here. Some of them are very interesting. That man in the car, Count Lippe. He comes here every year. He tells me fascinating things about the Far East – China and so on. He’s got some sort of a business in a place called Macao. It’s near Hong Kong, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, that’s right.’ So those turned-up eyes were a dash of Chinaman. It would be interesting to know his background. Probably Portuguese blood if he came from Macao.

They had reached the entrance. Inside the warm hall the girl said, ‘Well, I must run. Thank you again.’ She gave him a smile that, for the benefit of the watching receptionist, was entirely neutral. ‘I hope you enjoy your stay.’ She hurried off towards the treatment-rooms. Bond followed, his eyes on the taut swell of her hips. He glanced at his watch and also went down the stairs and into a spotlessly white basement that smelt faintly of olive oil and Aerosol disinfectant.

Beyond a door marked ‘Gentlemen’s Treatment’ he was taken in hand by an indiarubbery masseur in trousers and singlet. Bond undressed and with a towel round his waist followed the man down a long room divided into compartments by plastic curtains. In the first compartment, side by side, two elderly men lay, the perspiration pouring down their strawberry faces, in electric blanket baths. In the next were two massage tables. On one, the pale, dimpled body of a youngish but very fat man wobbled obscenely beneath the pummelling of his masseur. Bond, his mind recoiling from it all, took off his towel and lay down on his face and surrendered himself to the toughest deep massage he had ever experienced.

Vaguely, against the jangling of his nerves and the aching of muscles and tendons, he heard the fat man heave himself off his table and, moments later, another patient take his place. He heard the man’s masseur say, ‘I’m afraid we’ll have to have the wristwatch off, sir.’

The urbane, silky voice that Bond at once recognised said with authority, ‘Nonsense, my dear fellow. I come here every year and I’ve always been allowed to keep it on before. I’d rather keep it on, if you don’t mind.’

‘Sorry, sir.’ The masseur’s voice was politely firm. ‘You must have had someone else doing the treatment. It interferes with the flow of blood when I come to treat the arm and hand. If you don’t mind, sir.’

There was a moment’s silence. Bond could almost feel Count Lippe controlling his temper. The words, when they came, were spat out with what seemed to Bond ludicrous violence. ‘Take it off then.’ The ‘damn you’ didn’t have to be uttered. It hung in the air at the end of the sentence.

‘Thank you, sir.’ There was a brief pause and then the massage began.

The small incident seemed odd to Bond. Obviously one had to take off one’s wristwatch for a massage. Why had the man wanted to keep it on? It seemed very childish.

‘Turn over, please sir.’

Bond obeyed. Now his face was free to move. He glanced casually to his right. Count Lippe’s face was turned away from him. His left arm hung down towards the floor. Where the sunburn ended, there was a bracelet of almost white flesh at the wrist. In the middle of the circle where the watch had been there was a sign tattooed in red on the skin. It looked like a small zigzag crossed by two vertical strokes. So Count Lippe had not wanted this sign to be seen! It would be amusing to ring up Records and see if they had a line on what sort of people wore this little secret recognition sign under their wristwatches.

3

The Rack

At the end of the hour’s treatment Bond felt as if his body had been eviscerated and then run through a wringer. He put on his clothes and, cursing M, climbed weakly back up the stairs into what, by comparison with the world of nakedness and indignities in the basement, were civilised surroundings. At the entrance to the main lounge were two telephone booths. The switchboard put him through to the only Headquarters number he was allowed to call on an outside line. He knew that all such outside calls were monitored. As he asked for Records, he recognised the hollowness on the line that meant the line was bugged. He gave his number to Head of Records and put his question, adding that the subject was an Oriental probably of Portuguese extraction. After ten minutes Head of Records came back to him.

‘It’s a Tong sign.’ His voice sounded interested. ‘The Red Lightning Tong. Unusual to find anyone but a full-blooded Chinaman being a member. It’s not the usual semi-religious organisation. This is entirely criminal. Station H had dealings with it once. They’re represented in Hong Kong, but their headquarters are across the bay in Macao. Station H paid big money to get a courier service running into Pekin. Worked like a dream, so they gave the line a trial with some heavy stuff. It bounced, badly. Lost a couple of H’s top men. It was a double-cross. Turned out that Redland had some sort of a deal with these people. Hell of a mess. Since then they’ve cropped up from time to time in drugs, gold smuggling to India, and top-bracket white slavery. They’re big people. We’d be interested if you’ve got any kind of a line.’

Bond said, ‘Thanks, Records. No, I’ve got nothing definite. First time I’ve heard of these Red Lightning people. Let you know if anything develops. So long.’

Bond thoughtfully put back the receiver. How interesting! Now what the hell could this man be doing at Shrublands? Bond walked out of the booth. A movement in the next booth caught his eye. Count Lippe, his back to Bond, had just picked up the receiver. How long had he been in there? Had he heard Bond’s inquiry? Or his comment? Bond had the crawling sensation at the pit of his stomach he knew so well – the signal that he had probably made a dangerous and silly mistake. He glanced at his watch. It was seven thirty. He walked through the lounge to the sun-parlour where ‘dinner’ was being served. He gave his name to the elderly woman with a wardress face behind a long counter. She consulted a list and ladled hot vegetable soup into a plastic mug. Bond took the mug. He said anxiously, ‘Is that all?’

The woman didn’t smile. She said severely, ‘You’re lucky. You wouldn’t be getting as much on Starvation. And you may have soup every day at midday and two cups of tea at four o’clock.’

Bond gave her a bitter smile. He took the horrible mug over to one of the little café tables near the windows overlooking the dark lawn and sat down and sipped the thin soup while he watched some of his fellow inmates meandering aimlessly, weakly, through the room. Now he felt a grain of sympathy for the wretches. Now he was a member of their club. Now he had been initiated. He drank the soup down to the last neat cube of carrot and walked abstractedly off to his room, thinking of Count Lippe, thinking of sleep, but above all thinking of his empty stomach.

After two days of this, Bond felt terrible. He had a permanent slight nagging headache, the whites of his eyes had turned rather yellow, and his tongue was deeply furred. His masseur told him not to worry. This was as it should be. These were the poisons leaving his body. Bond, now a permanent prey to lassitude, didn’t argue. Nothing seemed to matter any more but the single orange and hot water for breakfast, the mugs of hot soup, and the cups of tea which Bond filled with spoonfuls of brown sugar, the only variety that had Mr Wain’s sanction.

On the third day, after the massage and the shock of the Sitz baths, Bond had on his programme ‘Osteopathic Manipulation and Traction’. He was directed to a new section of the basement, withdrawn and silent. When he opened the designated door he expected to find some hairy H-man waiting for him with flexed muscles. (H-man, he had discovered, stood for Health-man. It was the smart thing to call oneself if you were a naturopath.) He stopped in his tracks. The girl, Patricia something, whom he had not set eyes on since his first day, stood waiting for him beside the couch. He closed the door behind him and said, ‘Good lord. Is this what you do?’

She was used to this reaction of the men patients and rather touchy about it. She didn’t smile. She said in a businesslike voice, ‘Nearly twenty per cent of osteopaths are women. Take off your clothes, please. Everything except your pants.’ When Bond had amusedly obeyed she told him to stand in front of her. She walked round him, examining him with eyes in which there was nothing but professional interest. Without commenting on his scars she told him to lie face downwards on the couch and, with strong, precise and thoroughly practised holds, went through the handling and joint-cracking of her profession.

Bond soon realised that she was an extremely powerful girl. His muscled body, admittedly unresistant, seemed to be easy going for her. Bond felt a kind of resentment at the neutrality of this relationship between an attractive girl and a half-naked man. At the end of the treatment she told him to stand up and clasp his hands behind her neck. Her eyes, a few inches away from his, held nothing but professional concentration.

She hauled strongly away from him, presumably with the object of freeing his vertebrae. This was too much for Bond. At the end of it, when she told him to release his hands, he did nothing of the sort. He tightened them, pulled her head sharply towards him, and kissed her full on the lips. She ducked quickly down through his arms and straightened herself, her cheeks red and her eyes shining with anger. Bond smiled at her, knowing that he had never missed a slap in the face, and a hard one at that, by so little. He said, ‘It’s all very well, but I just had to do it. You shouldn’t have a mouth like that if you’re going to be an osteopath.’

The anger in her eyes subsided a fraction. She said, ‘The last time that happened, the man had to leave by the next train.’

Bond laughed. He made a threatening move towards her. ‘If I thought there was any hope of being kicked out of this damn place I’d kiss you again.’

She said, ‘Don’t be silly. Now pick up your things. You’ve got half an hour’s Traction.’ She smiled grimly. ‘That ought to keep you quiet.’

Bond said morosely, ‘Oh, all right. But only on condition you let me take you out on your next day off.’

‘We’ll see about that. It depends how you behave at the next treatment.’ She held open the door. Bond picked up his clothes and went out, almost colliding with a man coming down the passage. It was Count Lippe, in slacks and a gay windcheater. He ignored Bond. With a smile and a slight bow he said to the girl, ‘Here comes the lamb to the slaughter. I hope you’re not feeling too strong today.’ His eyes twinkled charmingly.

The girl said briskly, ‘Just get ready, please. I shan’t be a moment putting Mr Bond on the Traction table.’ She moved off down the passage with Bond following.

She opened the door of a small anteroom, told Bond to put his things down on a chair, and pulled aside plastic curtains that formed a partition. Just inside the curtains was an odd-looking kind of surgical couch in leather and gleaming aluminium. Bond didn’t like the look of it at all. While the girl fiddled with a series of straps attached to three upholstered sections that appeared to be on runners, Bond examined the contraption suspiciously. Below the couch was a stout electric motor on which a plate announced that this was the Hercules Motorised Traction Table. A power drive in the shape of articulated rods stretched upwards from the motor to each of the three cushioned sections of the couch and terminated in tension screws to which the three sets of straps were attached. In front of the raised portion where the patient’s head would lie, and approximately level with his face, was a large dial marked in lbs-pressure up to 200. After 150 lbs the numerals were in red. Below the headrest were grips for the patient’s hands. Bond noted gloomily that the leather on the grips was stained with, presumably, sweat.

‘Lie face downwards here, please.’ The girl held the straps ready.

Bond said obstinately, ‘Not until you tell me what this thing does. I don’t like the look of it.’

The girl said impatiently, ‘This is simply a machine for stretching your spine. You’ve got some mild spinal lesions. It will help to free those. And at the base of your spine you’ve got some right sacroiliac strain. It’ll help that too. You won’t find it bad at all. Just a stretching sensation. It’s very soothing really. Quite a lot of patients fall asleep.’

‘This one won’t,’ said Bond firmly. ‘What strength are you going to give me? Why are those top figures in red? Are you sure I’m not going to be pulled apart?’

The girl said with a touch of impatience, ‘Don’t be silly. Of course if there was too much tension it might be dangerous. But I shall be starting you at only 90 lbs and in a quarter of an hour I shall come and see how you’re getting on and probably put you up to 120. Now come along. I’ve got another patient waiting.’

Reluctantly Bond climbed up on the couch and lay on his face with his nose and mouth buried in a deep cleft in the headrest. He said, his voice muffled by the leather, ‘If you kill me, I’ll sue.’

He felt the straps being tightened round his chest and then round his hips. The girl’s skirt brushed the side of his face as she bent to reach the control lever beside the big dial. The motor began to whine. The straps tightened and then relaxed, tightened and relaxed. Bond felt as if his body was being stretched by giant hands. It was a curious sensation, but not unpleasant. With difficulty Bond raised his head. The needle on the dial stood at 90. Now the machine was making a soft iron hee-hawing, like a mechanical donkey, as the gears alternatively engaged and disengaged to produce the rhythmic traction.

‘Are you all right?’

‘Yes.’ He heard the girl pass through the plastic curtains and then the click of the outer door. Bond abandoned himself to the soft feel of the leather at his face, to the relentless intermittent haul on his spine and to the hypnotic whine and drone of the machine. It really wasn’t too bad. How silly to have had nerves about it!

A quarter of an hour later he heard again the click of the outside door and the swish of the curtains.

‘All right?’

‘Fine.’

The girl’s hand came into his line of vision as she turned the lever. Bond raised his head. The needle crept up to 120. Now the pull was really hard and the voice of the machine was much louder.

The girl put her head down to his. She laid a reassuring hand on his shoulder. She said, her voice loud above the noise of the gears, ‘Only another quarter of an hour to go.’

‘All right.’ Bond’s voice was careful. He was probing the new strength of the giant haul on his body. The curtains swished. Now the click of the outside door was drowned by the noise of the machine. Slowly Bond relaxed again into the arms of the rhythm.

It was perhaps five minutes later when a tiny movement of the air against his face made Bond open his eyes. In front of his eyes was a hand, a man’s hand, reaching softly for the lever of the accelerator. Bond watched it, at first fascinated, and then with dawning horror as the lever was slowly depressed and the straps began to haul madly at his body. He shouted – something, he didn’t know what. His whole body was racked with a great pain. Desperately he lifted his head and shouted again. On the dial, the needle was trembling at 200! His head dropped back, exhausted. Through a mist of sweat he watched the hand softly release the lever. The hand paused and turned slowly so that the back of the wrist was just below his eyes. In the centre of the wrist was the little red sign of the zigzag and the two bisecting lines. A voice said quietly, close up against his ear, ‘You will not meddle again, my friend.’ Then there was nothing but the great whine and groan of the machine and the bite of the straps that were tearing his body in half. Bond began to scream, weakly, while the sweat poured from him and dripped off the leather cushions on to the floor.

Then suddenly there was blackness.