Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Fitzcarraldo Editions

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

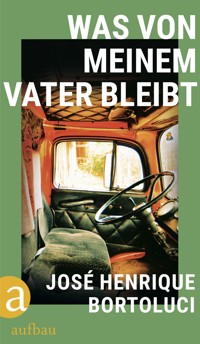

In What Is Mine, sociologist José Henrique Bortoluci uses interviews with his father, Didi, to retrace the recent history of Brazil and of his family. From the mid-1960s to the mid-2010s, Didi's work as a truck driver took him away from home for long stretches at a time as he crisscrossed the country and participated in huge infrastructure projects including the Trans-Amazonian Highway, a scheme spearheaded by the military dictatorship of the time, undertaken through brutal deforestation. An observer of history, Didi also recounts the toll his work has taken on his health, from a heart attack in middle age to the cancer that defines his retirement. Bortoluci weaves the history of a nation with that of a man, uncovering parallels between cancer and capitalism – both sustained by expansion, both embodiments of 'the gospel of growth at any cost' – and traces the distance that class has placed between him and his father. Influenced by authors such as Annie Ernaux and Svetlana Alexievich, What Is Mine is a moving, thought-provoking and brilliantly constructed examination of the scars we carry, as people and as countries.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 188

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

2

‘Powerful in its atomization of the Brazilian style of “capitalist devastation” that goes by the name of progress, movingly tender in its evocation of an Odysseus of a father, a long-distance trucker who plays a part in the construction of the Trans-Amazonian Highway, this is a memoir like no other. I read it in one great gulp, unable to put it down. Brilliant!’

— Lisa Appignanesi, author of Everyday Madness

‘A political document told as memoir, this is a book of incredible beauty and insight, one which demonstrates one of the greatest truths: that our lives, and the lives of our families, are inextricably bound to the structures of class, economics, and history they were born into.’

— Madeleine Watts, author of The Inland Sea

‘What Is Mine is an unforgettable oral history of truck driving along the potholed roads carving up the Amazon rainforest: bandits, sleep deprivation, beef barbecued on the engine. It is also an incisive political critique of ecocidal ideas of “progress”, a powerful reflection on the ways labour shapes a human body, and a loving exploration of a relationship between a father and son. It already has the feel of a classic.’

— Caleb Klaces, author of Fatherhood

‘José Henrique Bortoluci’s What Is Mine is an extraordinarily powerful portrait of a man’s life, a country’s course and the “ancient marriage between shamelessness and devastation” in Brazilian history. Tender, thought-provoking, incisive and humane, it’s a deeply intelligent road movie for the soul. A beautiful and moving journey through a trucker’s memories of a changing nation and a vital meditation on class, capitalism and, above all else, the search for human dignity. Utterly transfixing.’

— Julian Hoffman, author of Irreplaceable3

WHAT IS MINE

JOSÉ HENRIQUE BORTOLUCI

Translated by

RAHUL BERY

CONTENTS

9

‘There’s no text without filiation.’

— Roland Barthes

‘In any case, we desire a miracle of eight million kilometres for Brazil.’

— Graciliano Ramos10

I. REMEMBER AND TELL MY STORY

‘My father always away and his absence always with me. And the river, always the river, perpetually renewing itself.’

— João Guimarães Rosa, ‘The Third Bank of the River’

Remember, your dad helped build this airport so you could fly. I hear my father’s words every time I catch a flight from Guarulhos Airport. And while I always remembered, it has taken me some time to truly understand. The truck driver father visits his home, his wife and his kids. He comes and, before long, leaves again. He always came with his truck, they were a duo, almost a single entity, both too much and not enough, imposing and ephemeral. As a boy, I always wanted them to stay, wanted them to go, wanted to go with them.

He said these exact words when we were on our way to that airport in 2009, the day I left to do my PhD in Sociology in the United States. During the months I spent preparing for the move, I showed him the state of Michigan several times on the map. We calculated the distance between Jaú and Ann Arbor, where I would live for the next six years. My father doesn’t understand the world of universities, is unfamiliar with its nomenclature and rituals. He has only a vague notion of what it means to do a PhD. But he does understand distances.

Eight thousand kilometres separate the two cities. This number failed to impress him. He had covered hundreds of times that distance over five decades as a truck driver. One day he asked me to calculate how many times you could travel around the world with the distance he had covered as a driver.12

Could it get you to the moon?

In my father’s imagination, a journey from Earth to the moon is a more solid concept than my life as an academic, teacher and writer.

Words are roads. They’re what we use to connect the dots between the present and a past we no longer have access to.

Words are scars, the remnants of our experiences of cutting and sewing up the world, gathering its pieces, tying back together the things that had the temerity to scatter.

Words were the world my father brought with him in his truck during my childhood. They resounded by themselves – cabin, Trans-Amazonian, trailer, highway, Pororoca, Belém, homesickness – or formed part of narratives about a world that seemed impossibly large. I had to imagine them in all their colours, record them in my memory and cling onto them, because soon my father would leave and he wouldn’t be back for forty or fifty days.

Most of these stories were reconstructions of events he had witnessed or heard about on the road. Others were fantastical creations: the epic hunt for a giant bird in Amazonia, the fable of a sheep he found on the highway and took on as his cabin companion, journeys over the Bolivian border with groups of hippies in the 1970s. Many, I imagine, mixed fact and fantasy. He described in detail seeing UFOs on a highway in Mato Grosso, nights spent in isolated indigenous villages, brawls with armed soldiers, Homeric rescues of trucks that had fallen into ravines.

___

13His name is José Bortoluci. At home, everyone calls him Didi, but on the road he was always Jaú. The fifth child in a family of nine siblings, he was born in December 1943, in the rural part of that city located in the interior of São Paulo state.

My father studied until he was nine, worked on the family’s small farm from the age of seven, moved with them to the city at fifteen. He was only twenty-two when he became a truck driver. I was young, but I was as brave as a lion. He started driving trucks in 1965 and retired in 2015. The country that he traversed and helped to build was very different then from how it is now, but in recent years there has been a sense of familiarity: a country seized by frontier logic, the principle of expansion at any cost, the ‘colonization’ of new territories, environmental vandalism, the slow and clumsy construction of an ever more unequal consumer society. Roads and trucks occupy a key position in this fantasy of a developed nation in which forests and rivers give way to highways, prospecting, pasture and factories.

The truck would bring my father, his dirty clothes and not enough money. My mother would agonize and work overtime altering clothes while looking after her two sons.

I am the oldest son. I understood from very early on that our family life was overshadowed by the risk of extreme poverty, uncontrolled inflation and premature illness.

We got used to living in a state of uncertainty, at the mercy of bank accounts that were on the brink of collapse, and with strict limits on what we could eat, experience, wish for. We never went hungry, though at times this was only thanks to help from neighbours, friends and 14relatives when my family’s income ran out and my father’s debts were at their peak. I do, however, remember growing accustomed to that ‘half-starvation you feel at the smell of dinner coming from the doors of the more well-to-do’, as the Danish poet Tove Ditlevsen described it in her memoirs. A persistent semi-starvation which we learnt to downplay, misleadingly labelling it as ‘cravings’. In my case, the sensation was further incited by the adverts for sweet yoghurts and cereals that flooded TVs in the 1980s and 1990s and which, to this day, provoke an uncomfortable temptation in me, emerging like a discordant echo of past desires.

A good proportion of the clothes my brother and I wore during the first twenty years of our lives had been bought second-hand, donated by an uncle or aunt or some family friends, or purchased at charity jumble sales. My mother, whose work as a seamstress helped with household expenses, always made a point of keeping them impeccably clean and repairing any blemishes. The newer ones were ‘church clothes’, the older ones for wearing on weekdays.

Our house was small and stuffy, built bit by bit at the rear of my grandparents’ house. The uncovered kitchen flooded at the first sign of heavy rain. This was the room where my brother and I studied after school and where my mother worked all day. The soundtrack to our lives was composed of the noise from her sewing machine and the songs on the radio, tuned in to some local station. Endless work, little money, and no time to undo what had been woven: there is no Ulysses, no Penelope in this story.

My mother hated him smoking inside the house. So, whenever he was in Jaú, my father spent a lot of time sitting on a step between the kitchen and the small yard 15connecting our home to my grandparents’ house. That step, the threshold between inside and out, made concrete the uncertain status that my father occupied for me, a man who was both an essential part of my life and a seasonal visitor who disrupted the rhythm of our days.

There were always bills to pay. A silent terror associated with the expression ‘overdraft’, which I must have learnt in my earliest years, always hung in the ether at home. And which clung, most of all, to the word ‘debt’: a suffocating word which spread through the rooms like cigarette smoke. That word arrived with the truck and stayed even after my father had left. To this day, hearing someone say ‘debt’ brings to mind the smell of cigarettes and the image of that step in my childhood home.

There is almost no written record of his fifty years on the road – just two postcards sent to my mother and some yellowing invoices in the drawer. But he remembers a lot, and his ‘madeleines’ emerge when you least expect it: an image on TV makes him remember when he went for several days without food, stuck on a muddy track in southern Pará; any news of a serious accident on the road opens up a whole trove of stories about the many he witnessed and the handful he was involved in; stories of remote villages, of poachers, of distant tropical landscapes, of companions – some loyal, others not, most of them dead. Narratives that march along and spring back to life without the help of photos or notes. The only thing anchoring them is the memory of a man who is nearly eighty, now somewhat garbled by time.

I’ve seen so many things, son. I should’ve written them down, taken photos. We didn’t have mobiles or anything like that back then. They didn’t exist. The only thing I could’ve taken them with would have been a Kodak, those black and white 16cameras, but your old man never had one. Because if I did have a record of all the things I’ve done you’d be so proud of your dad. It may seem like I don’t have much to show for it, but what is mine is everything I saw and recorded in my memory. So all I can do is try to remember and tell my story.

Photos showing my father on his travels during this five-decade period are also few and far between. Most of the ones that do exist record his presence on commemorative dates, when he was with his family in Jaú.

In one of those images, the two of us are in our kitchen at home. It’s my first birthday in November 1985. He is holding me up in the air while my cousins sing ‘Happy Birthday’ around the cake. The scene is made up of colourful balloons, blue plastic cups and a large glass bottle of Coca-Cola. His hands hold me tight and I appear confident; my body is erect, with only the tips of my toes, inside my tiny red plimsolls, brushing against the table. I’m looking at the camera, my eyes open and alert, while he looks at me. My hair was fairer than it is today and his hadn’t yet lost its colour; it’s combed backwards, long, shiny and slathered with Trim, the styling cream he used for decades, until recently he decided he wouldn’t use it any more and would keep his hair short – the same haircut my grandfather had in his old age. My small, white hands rest on my father’s heavily sunburnt skin, distinguished by an uneven tan, typical of truck drivers, which he still has to this day, though now his skin is discoloured and speckled with blotches and scars. One small hand on his arm, another on the fingers of one of the hands holding me. This is one of the only photographs in which my mother does not appear (did she take it?).

A couple of days after the party, my father would go back on the road before returning to Jaú a few weeks later, 17for Christmas maybe, or for the birth of my brother six weeks after. In a journal that my mother kept for years, from the beginning of her relationship with my father in 1976 until shortly after my birth, she describes this time, stretched out by distance: ‘How I love you Didi, I’d repeat these words a million times if you were right here by my side all day. But I know that’s impossible because I have to work and so do you, so that we can achieve our dream. Distance creates longing, but never forgetting.’

I don’t know what the dream she talks about is or if, now, she believes she has achieved it. This entry is dated 3 June 1976, but the tone used in these lines is repeated dozens of times in the pages of her journal over the nine years that follow.

Isolated at home because of the collapse of the health system in the Jaú region, one of the worst affected by the coronavirus during those sorrowful early days of 2021, my father looked animated as he told his stories. I began recording them in January of that year, during successive visits to my parents, always on warm nights after dinner. He preferred to talk to me in the backyard, lying in an old hammock he’d bought in the 1970s in some city in Piauí, which accompanied him on his travels for years.

This conversation we’re having right now, son, you’ll have to keep it in your memory, because you know your dad won’t be around for long.

After one of these recording sessions, he wondered out loud if he would live to see the book published. I had been wondering the same thing since December 2020, when he told me for the first time about the strange abdominal pains he was having and the blood that had been appearing in his faeces for several weeks.18

As I write these lines, in early 2021, my father, at seventy-eight, is beginning treatment for bowel cancer. The tumour emerged in his body before spreading throughout our family life and into this book.

The cancer was diagnosed on 29 December 2020, before I began a series of interviews with him, but after I’d told him I wanted to record our conversations, hear him talk about the road, the story of his life, his ‘yarns’, memories and anything else he wanted to say.

The first time I told him I was writing a book, he asked if it would be a good thing for me. Yes, I answered, I think so. If it’s good for you, then I’m happy.

The day before the diagnosis, I was in São Paulo and had spent the whole afternoon staring at maps of Amazonian rivers and the roads of the north of the country. I read about periods of flooding and dry spells, about the most suitable times for visiting river beaches, navigating the smaller streams and observing the surrounding jungle. I started planning a journey across the entire Trans-Amazonian Highway (how would I manage when I can’t even drive?). I ordered three maps of the region, the huge ones that you have to fold and unfold, as well as detailed road maps which showed the smaller roads that cut through the rainforest, those asphalt anti-rivers my father helped build in the region he traversed for decades.

That same night, a pipe burst in my apartment. The water flooded the entire bathroom, part of the kitchen, the utility room and the entrance hallway before leaking out of the apartment. This attracted the attention of the building’s concierge, who called me, concerned. I was out but managed to get back quickly. The living room was the worst hit, completely covered by a thick layer of liquid, a foot of water on the wooden floor, like a gently oscillating 19mirror, reflecting lampshades, armchairs, plants and the image of my own body. That small apartment in the centre of São Paulo with its modern furniture, which had finally allowed me to create something resembling a middle-class adult home – so different from the house I grew up in – had been brought down by water that came up to my shins.

I felt jittery and fearful. The out-of-place water felt too theatrical, an ill omen, as if it had come straight out of one of Marguerite Duras’s colonial novels or a surrealist painting. The water had soaked my shoes, the hem of my trousers, pillows, wooden furniture, and was seeping into thousands of tiny cracks in the floor tiles, warping them forever. In my room, the cat was hiding under the bed, one of the few places untouched by the water.

There’s a sense of overflow with cancer too: it’s matter in the wrong place, in frenetic expansion.

I called Jaú the following morning and asked my mother what the diagnosis was from the bowel biopsy they had taken at the laboratory. She struggled to pronounce the strange word. She decided to spell it out and I wrote it down on a piece of paper: a-d-e-n-o-c-a-r-c-i-n-o-m-a. Letter by letter the word formed, each letter a cell joining onto others to form a new meaning, an out-of-place word-mass.

A rapid Google search explained that ‘adenocarcinoma’ is the medical term for a certain kind of tumour that affects epithelial glandular tissues, such as those in the rectum, as was my father’s case. This was the first of many words to enter our growing family lexicon over the months to come. Illness is not simply a biological phenomenon, but also heralds a new kingdom of words, a mesh of vocabulary that colonizes our everyday language. 20We have all experienced this in recent years, when the coronavirus forced us to dive into a terminological lake of ‘moving averages’, ‘protein spikes’, ‘herd immunity’, ‘immunity window’ and so on. In my family’s case, we were also surrounded by words in rapid proliferation that began to circulate around my father’s body, connecting to it and altering its dimensions.

After that inaugural period, other words and expressions piled up: ‘stoma’, ‘colostomy’, ‘tumour markers’, ‘PET scan’, ‘colorectal tumour’. And ‘malignant neoplasia’, the cruellest of all, perhaps because it suggests a kind of moral drama, perhaps because it is the most honest.

In the first medical consultations, I quickly learn that the taboo surrounding the word ‘cancer’ isn’t restricted to the world of patients and their family members. A careful observer would have to go to some lengths to find it mentioned in reports, exams, hospital routines, conversations with doctors and nurses. We still describe cancer patients as ‘battling a disease’, and you don’t have to have been around for long to realize that the ‘disease’ being battled is never flu, cholera or pneumonia. Its absence seems to make it more alive – in this silence, we all know it’s cancer that’s being talked about.

Susan Sontag famously wrote that ‘[e]veryone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.’ The American writer was very familiar with this condition of double belonging; she faced a series of relapses, and ensuing cancer treatment, over the last thirty years of her life.

My father travels with this new passport. The imprints 21he now bears and the rituals to which he is subjected – the perennial colostomy bag, the intermittent urinary catheter, the frequent hospital visits, the operations – all signal his citizenship of the world of the sick.

In a well known piece of dialogue in Ernest Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises, a war veteran and bankrupt former millionaire explains to a colleague how his economic ruin came to pass:

‘“How did you go bankrupt?”

“Two ways. Gradually and then suddenly.”’

Observing my father over the last few years, I have learnt that growing old also obeys this double rhythm. You grow old gradually: muscles lose their strength, new pains emerge in the body, cataracts cloud your vision, your hearing stops catching nuances, familiar stairs become Olympic-level obstacles; surgery, hospital stays and the deaths of acquaintances begin to dominate conversations with friends and relatives of the same age.

You also grow old suddenly. My father’s great leap came with the diagnosis of bowel cancer and the treatment that followed.

Life passes quickly after forty, but it’s been flying by since I found out about the illness.

‘Severe heart disease’, the patient records state; ‘Your father is a complicated patient,’ the doctors who see him say; ‘We have fewer treatment options with you, sir,’ the oncologist repeats at every consultation.

Memories emerge and intertwine: he remembers that his father and two of his brothers died of bowel cancer. My grandma Maria had it too. She had surgery on her tumour the day Brasília was inaugurated. She lived a good while after though, I don’t think it’s what killed her.

The fragile condition of his heart means the doctors 22cannot carry out the extensive surgery to remove the tumour. Or at least that’s what the first surgeon concluded, but we’re rarely fully convinced by the medical pathways set out before us. Where health is concerned, doubt becomes a permanent condition. We never felt persuaded they couldn’t operate and remove the tumour, while also being terrified this was indeed the case.

I write between two devastations. One of them afflicts my father’s body. The other is collective, national. In recent years we have been laid to waste by a macabre political experiment: the great evil that did nothing but bare its teeth at the growing pile of dead bodies we’ve long ago given up trying to keep count of.