6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

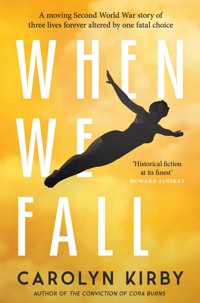

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

England, 1943 Lost in fog, pilot Vee Katchatourian is forced to make an emergency landing where she meets enigmatic RAF airman Stefan Bergel, and then can't get him out of her mind. In occupied Poland, Ewa Hartman hosts German officers in her father's guest house, while secretly gathering intelligence for the Polish resistance. Mourning her lover, Stefan, who was captured by the Soviets at the start of the war, Ewa is shocked to see him on the street one day. Haunted by a terrible choice he made in captivity, Stefan asks Vee and Ewa to help him expose one of the darkest secrets of the war. But it is not clear where everyone's loyalties lie until they are tested. Published to coincide with the 75th anniversary of VE Day and based on WWII atrocity the Katyn Massacre, When We Fall is a moving story of three lives forever altered by one fatal choice.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR WHEN WE FALL

‘Such a skilfully constructed novel about one of the less well trodden events of the war peopled by complex, sympathetic characters. Compelling and moving – it’s a wonderful read which often sends the pulse rate into overdrive. I loved it’ – Annie Murray, author of Girls in Tin Hats

‘An engaging and elegantly written novel on the grim realities of war, and the moral choices that can result. Highly recommended’ – Roger Moorhouse, author of First to Fight and Berlin at War

‘It’s a tale of tragedy and brutality, with characters that are so well-drawn they practically get up and walk from the page... I simply wanted to pick it up when I had finished and start over again’ – Jenny Quintana, author of The Missing Girl

‘A meticulously researched novel of love, intrigue and betrayal... reveals how in war truth so often falls victim to expediency. In a story where loyalties are called into question, she kept me guessing to the final page. Carolyn’s writing is so vivid and so well researched – I was sitting in the cockpit with Vee and walking the streets of Poznań with Ewa!’ – Anita Frank, author of The Lost Ones

‘A vivid novel that stays with you long after you reach the final page’ – Fiona Erskine, author of The Chemical Detective

‘The story never let me go for one second’ – GJ Minett, author of Lie in Wait

‘Carolyn has an effortless style that transported me back in time’ – Emily Elgar, author of If You Knew Her

‘Memorably descriptive prose... Carolyn Kirby is a past-mistress of the little twist, the soupcon of uncertainty that creates an atmosphere of tension’ – Gaynor Arnold, author of Girl in a Blue Dress

‘Scores of senior Polish figures including President Kaczyński have died in a plane crash in Russia.

Polish and Russian officials said that no one survived after the plane hit trees as it approached Smolensk airport in thick fog.

Poland’s army chief, central bank governor, MPs and leading historians were among at least 90 passengers who died.

Prime Minister Donald Tusk said that the crash was the most tragic event in the country’s post-war history.

The Polish delegation was flying from Warsaw to mark the 70th anniversary of the Katyn massacre of more than 20,000 Polish officers by Soviet forces during the Second World War…’

BBC News

10 April 2010

10 April 2010

Air

Bournemouth, England

Saturday 10 April 2010

The radio-voice stumbles over the names of the dead. Foreign syllables are tripping her up, like bodies strewn through wreckage. And at the sound of one of the mispronounced surnames my heart buckles. Did she just mention you? But, no. A lifetime has passed since I last heard anyone say your name. Then the announcer utters a Russian word without hesitation. Katyn. The place in the forest. A sick-taste of guilt rises and I flick the off-switch.

Outside through the kitchen window, high cloud films the sky like a girl’s well-brushed hair. Those gauzy cirrus clouds are so far away from us that their turbulence seems slight. But if you take your eyes off them for more than a moment, their icy formations will have altered forever.

You told me this as we stood on a wide grassy airfield that morning you first took me up. Look! you said, your rolled shirt sleeve falling back as you pointed at the clouds, they are moving faster than anything in the sky. In a leather flying-helmet and men’s slacks, I tapped sceptical fingers on my forearm. I don’t believe you, I said, they’re not moving at all. Your grin was still boyish as you squinted into the sunlight. All right then. Let me take you for a closer look.

And so you did. Up, up went the old bi-plane in a climb so fast and so vertical that it could not last. At the top of the loop, the engine slowed then coughed into silence. We sat suspended in air. Then we began to fall; slowly at first, then faster, faster, into a gut-churning plunge. I forced my eyes to stay open. A farmhouse loomed below, white sheets waving on a washing line. Hang on, I thought, maybe this isn’t a joke. The white sheets grew, filling my goggles. I pictured myself slamming into the farmhouse’s orange roof, saw white lilies on my coffin and tears rolling into my father’s moustache. But then, when there was nowhere left to fall, the engine hiccupped and the plane, as you knew it would, swooped back up into the crisp air.

You had to help me out of the open cockpit. I couldn’t walk. Did you not like it? you asked, smirking. Quite a thrill, I suppose, I replied, cool as you like.

You raised an eyebrow, fixing me with your pale blue stare. Then I’ll have to think of something even more exciting. My gaze, always bold, did not waver from yours. And I let my fingertip rise to touch the V of tanned skin inside your unbuttoned collar.

No photograph of you exists anywhere on the planet. I used to think that I could not bear to stay on earth either unless I could see, just once more, your face squinting up at cirrus clouds. But here, implausibly, I still am. Along with the only relic of you that remains.

I drag the chair from the kitchen table and climb somehow on to the seat. But even on tip-toes, I seem no longer able to reach the back of the top cupboard. My fingers pat around unseen knick-knacks and forgotten paperwork; a tight wad of thirty-year-old tax records for The South Coast School of English; the crinkle of an aerogram with a West German stamp. My ring taps against the smooth glass curves of a lighthouse filled with multi-coloured sand. Mine is not much of a wedding ring; the plain copper is dull and worn, and it is on the wrong hand. But it tells me, even if it lies, that you loved me more than the foreign girl.

Reaching into the sandwich of paper, I edge my thumb and forefinger around the logbook and gain some purchase on the grainy cover. Inside, your writing still bounds across the page, through flying times and aircraft types, with such youthful elegance it is as good as a portrait of your face.

I pull harder and the logbook slides forward. Then suddenly it pops free. The release uncorks a shower of long-paid bills and unanswered letters that rocks me back on to my heels. And then forward. Slowly at first, but inescapably, I lose my connection to the chair and start to fall. I become as free and untethered from the earth as that girl in the bi-plane, although this time the ground hits me and with a force that could have come from a thousand feet instead of two.

Tiles are cool under my cheek. Black spots dance across my eyes. Then the spots start swelling, joining, almost blotting out the paperwork that is scattered across the kitchen floor. But, just before blackness closes in, something glints at me through broken glass and sherbet sand. For there, on the faded blue cover of a Royal Air Force logbook, are your initials, SB, in still-shining gold.

Spring 1943

Stratus

Low blankets of dense grey cloud with clear air above. If very low-lying, stratus becomes mist or fog.

Essex, England

Wednesday 31 March

The Tiger’s yellow wings slice over sodden fields. Vee glances down then double-checks the map but all appears as it should. Printed red roads still match the pattern of snaking grey macadam on the ground. Ten more minutes and RAF Birch should be in sight.

But to the east, the air is murky; sea, sky and shore are merging. As Vee squints into the propeller haze, whiteness begins to blank out the earth. Her pulse quickens. Perhaps she should have taken the advice of that watch officer at Stradishall to give Birch a miss. But how would that have looked on her training record? They would think her slack or spineless. Not quite up to scratch.

Then, through a sudden clear hole, spidery roads sprout from the fat body of a village and Vee’s eyes jerk back to the map. Halstead perhaps? But the mist, damn it, has already shifted, swallowing the village up. Cloud tightens around the cockpit and Vee shoves the useless map under the seat. Now that she is flying blind, there is nothing left to see.

Sweat trickles into her brassiere and a corner of Vee’s brain enjoys the rush of adrenalin – the tightening of focus, the heightening of her senses. This is what she craved, after all, during those dull afternoons staring at a criss-cross of vapour trails through the factory office skylight. And the heat building inside her flying suit comes less from fear than from irritation; irritation with the watch officer whose warning of low cloud near the coast was not forceful enough to make her change course, and irritation with Captain Mills for tutting when she had asked, only last week, whether there would be any training to fly on instruments. Oh no, he had chided, we won’t be worrying your heads with that. You’ll be too busy keeping one eye on the ground and the other on the motoring map on your knee. It was hardly even a motoring map that she’d been given today – more like something that before the war would have come free with a Sunday newspaper. But any map would be useless now.

The engine drones on, oblivious to danger. Vee’s face, goggles and fleece collar are all soaking. Inside a clammy glove, one hand grips the control stick, trying to keep it motionless and perfectly upright as the other raises her goggles. But it is no better. The ground could be anywhere. Watery air coats Vee’s eyelids but her mouth is dry.

How long since she last saw the ground? A minute, or three? She has read somewhere that time is the most important thing to keep track of when flying blind, although she has no idea what comes next. She checks the altimeter. 500 ft. Too low. But going up is off limits. Captain Mills had pointed, smugly, at the instruction written in capitals into the ATA rule book: DO NOT, UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCES, TRY TO FIND YOUR WAY OUT OF MURK BY GOING OVER THE TOP. Because sunlight may lie just above this layer of cotton-wool cloud, but Vee knows that without reliable instruments or training in how to use them, the seductive prospect of clear air is a deathtrap. Fuel can so easily run out before the cloud that hides the ground ever does.

But does she dare go down? Her heart beats double time at the thought. Clear air may be only a few feet below the Tiger’s wheels. Or fog may drape right into the corduroy soil. Vee glances at the small wooden instrument panel even though she knows that at this height, the Tiger’s gauges cannot be trusted. She takes a proper breath. Fifty feet down is worth a try.

With her eyes on the altimeter, Vee pushes the control stick gently forward and feels the familiar downward lurch in her stomach. The needle descends. Five hundred; four fifty. The fog is dense with moisture. Black spots crowd across her vision as her eyes strain into the glare. Is something there, dark and shifting, not far below the plane? Is there? Good grief. Vapour suddenly clears and furrowed black earth looms up. The plane is not at four fifty. Nowhere near. Two hundred feet she’d guess, or less. Instinctively, she pulls back on the stick and the Tiger jumps up, top wings cutting at rags of cloud. But she rights the stick and the plane levels. Just above the telegraph poles will have to do.

Except that there are no telegraph poles here; there’s not much of anything. Ploughed fields give way to squashy-looking marshland, and then, across a line of listless surf, land turns into sea. The Tiger gives a cough as if to enquire, politely, if this is really the way that she wants to go. Sweat accumulates in Vee’s armpits and behind her knees.

Here comes land again, dull green and curlicued with marshy channels, and beyond it, another expanse of dark water. Vee’s eyes cast around for the horizon. Water. Marshland. Water again. And in the distance, embedded in a shroud of mist, an eerie green light. She blinks. The glow becomes more solid and more definitely green. It reflects vaguely in the approaching expanse of open water. Something must be illuminated out at sea. But what vessel would be lit up like a target practice for the Luftwaffe? Then the eerie light lengthens to a rectangle of green dots. A flare path. And inside it sits a dead-straight strip of concrete with a squat control tower to one side.

Vee feels a wave of hot relief pass through her. This is not Birch; too close to the coast for that, but any landing ground is better than a turnip field. Pressing a boot on to the rudder pedal, she banks the Tiger on to a low circuit around the aerodrome. The limp yellow windsock rises in a sluggish salute as she levels down towards the strip. She pulls up the nose into the faint headwind. Wheels skim clean concrete. There is a bump of touchdown but the rest of the run-in is satisfyingly smooth.

Vee steers the Tiger to a stop but lets the engine purr. On the roof of the control tower, inside a glass observation box, binoculars glint. They cannot, surely, object to her landing here. Anyone can get caught out by fog. She reaches down for the map and scans the jigsaw of green and blue for an aerodrome.

Then the Tiger rocks drunkenly to one side. An airman wearing a deflated life-vest has put his foot on the lower wing, weighing it down. His hand slices across his throat in a signal for Vee to cut the engine, but he is smiling. She reaches out to the switch beside the half-windscreen and flicks off the ignition. As the engine stutters into silence, she looks at the airman, and when his icily pale blue eyes meet hers, his smile collapses.

‘Mein Gott!’

Colour washes from him.

Vee tenses and unease needles the back of her neck. That last stretch of water… it could not possibly have been the North Sea, could it? And that bomber beside the runway is surely a Bristol Blenheim, not a Junckers 88… Her eyes search around for a familiar red and blue roundel. And, of course, the RAF symbol is there on the Blenheim’s fuselage. How could she be anywhere except England?

She turns back to the airman and realises how long she has been all but holding her breath. Her voice comes out clipped and shrill.

‘Where is this?’

Shakily, the airman’s smile returns. ‘You don’t know?’

‘No.’

‘Really?’

‘Why bother lighting a flare path unless you’re expecting people to become lost?’

‘Yes.’ His smile strengthens. ‘You are right.’

‘And if you told me to switch off the engine, you could have simply pointed me in the right direction and I would have got out of your way.’

‘But the sea fog is too heavy now for take-off.’

His accent is not strong but there is one, and she cannot quite place it. Could it really, somehow, be German? She hears her voice become brittle.

‘You seem rather reluctant to reveal our location.’

‘Classified information.’

‘What?’

He laughs. The sound is reassuring as well as infuriating.

‘No, no, I am sorry, a joke. Bradwell. This is RAF Bradwell Bay.’

‘Thank you.’

She looks back at the map and feels hotness in her face even though he can have no idea that she just imagined herself to have flown into Nazi-occupied Belgium. She hopes the airman might go away but he leans over her and points with a clean white finger. He must be a pilot; they can never resist a map.

‘We are here, see. Bradwell. Where did you come from?’

‘Sorry. Classified information.’

He nods sheepishly to one side indicating that they are even, now. But as she tries to look back at the map his eyes hold her. A dark ring around their paleness gives him a striking, foreign look. His smile grows warmer.

‘No, I am sorry. And I must give you something to make up for my bad joke. Tea, maybe?’

‘No need.’

‘Please, just wait here for a short time. Believe me, half of one hour will change everything.’

‘With the vis, you mean?’

He nods. ‘Cloud will soon disappear.’

Vee taps a finger on the buckle at her waist. He is probably right. And it would not be sensible to get even colder by sitting out here for half an hour.

‘All right.’

She snaps open the harness straps. The airman stretches to help her from the cockpit but she ignores his hand, hauling out the parachute and overnight bag behind her. She will not risk leaving them. Anything might happen to an unattended aeroplane, especially this close to enemy shores.

Only when Vee steps down on to the concrete does she realise that her feet are numb. The airman raises his arm, indicating the way and she tries not to let her legs collapse as she follows him. He seems to have thought better of offering to carry anything for her. Vee feels vaguely guilty for her sharpness.

‘Stradishall,’ she says.

‘Excuse me?’

‘That’s where I’ve come from, RAF Stradishall. Or at least, that’s where I last touched down. I set off on my cross-country this morning from Luton.’

He slides her a glance. ‘So what… what are you?’

‘A pilot.’

He winces and again she senses that she is being too sharp.

‘I’m Vee.’

His eyebrows exaggerate a frown. ‘Like V for victory?’

‘V for Valerie.’

‘Valerie.’ His tongue rolls around the syllables.

‘Vee,’ she corrects.

‘Please, excuse me. I must make an introduction.’ He gives a sharp nod and raps his heels together. ‘Flight Sergeant Stefan Bergel, 302 Squadron. How do you do?’

Vee tries not to laugh. ‘Pleased to meet you. Vee Katchatourian.’

She walks on and gives him a sideways look as he catches up. He is tall, even for a pilot. Every movement inside his baggy overalls has a hint of coiled energy. His face has an eager look.

‘You are Armenian, Vee?’

She does not miss a beat. ‘No. I’m English.’

Her voice has sharpened but actually she is impressed. She cannot remember the last time anyone got it right. And it is a perfectly fair question; a good many of the other cadets are from abroad. It is just that her senses are always primed for the usual reaction to her surname; the slight frown of incomprehension, the wince of embarrassment at her foreigness even though, despite her olive skin and hazel eyes, Vee is as English as anyone she knows.

She blinks sideways at Stefan Bergel. ‘But you’re not. English, that is.’

‘No, no, no!’ He chuckles and inclines his shoulder towards her, lifting the flattened yellow edge of the life-vest. ‘POLAND’ is embroidered on to the shoulder of his overalls.

‘I see.’

So, what he said before must have been in Polish, or perhaps it had just been My God, with that accent of his.

Grey fog swirls around the green flares. In the control tower, shadowy figures move around behind big windows criss-crossed with tape. Stefan raises a thumb in their direction then leads the way to a blackened wooden hut that even inside smells of creosote.

In the corner of the uncertainly furnished room, an urn steams on a ring-stained bench. An airman slumped in a saggy armchair snores. Vee drops her parachute pack to the floor and sits at a scuffed card table. She takes a gulp from the cup that Stefan puts down in front of her. Despite the steam, the tea is not very hot.

Stefan leans back and in his chair. ‘So. What do you think of our mess?’

‘Messy.’

‘We need more ladies to visit.’

‘To do the tidying?’

He laughs and his dark hair, wet from the fog, falls forward on to his brow. But beneath the smile, his pale eyes are fixed, unblinking, on Vee. This makes her feel awkward but also faintly excited. Luckily, the hut is too cold for her to have any urge to undo the collar of her Sidcot, or even take off her leather helmet. She must not be tempted to stay too long. Given that she hasn’t made her scheduled touchdown at Birch, Captain Mills might already be wondering where she and the Tiger have gone.

Stefan leans across the card table, half whispering. ‘Okay. I give in. I know you are not WAAF, so tell me what you are? Coastal command or civil aviation of some sort…?’

‘Of some sort, yes. Air Transport Auxiliary.’

‘Oh, yes. You deliver our new planes and take the knackered ones out of our way.’

She laughs. His English is good, but eccentric. ‘That’s right.’

‘And Luton is your base?’

Vee shakes her head. ‘White Waltham.’

‘Ah yes, near Northolt.’ He nods as he takes a sip of tea. ‘And giving radios to ATA pilots would make their navigation too easy?’

‘It would rather take the fun out of it, I suppose.’

‘Seriously?’

She laughs. ‘Of course not seriously.’

He looks a little hurt and again guilt folds through her. She cannot remember a man ever being so alert to what she has to say. It makes her feel older than him although clearly she is not. She takes a sip of cool tea then puts the saucerless cup on to the felt tabletop. A few dark hairs on Stefan’s wrist seem trapped in the steel links of his watch. It is all she can do not to run her finger around the rim of the strap and free them. She blinks the thought away. Her wits must be addled by the fog. She keeps a grip on the teacup with both hands.

‘There’s lots of reasons we don’t have radios. ATA often have to fly brand-new planes from the factory to maintenance units for the radios to be fitted there. So we have to learn to fly contact with the ground and not rely on wireless signals. And anyway, the channels have to be kept clear for you lot.’

‘So if sea fog comes down they don’t mind to lose a Tiger Moth and a lady pilot?’

‘They haven’t lost me, have they? I’m here.’

‘And I am most glad that you are.’

She thinks for a mortifying instant that he is going to take hold of her wrist just as she had imagined taking his. But instead he smoothes back the wet hair from his brow.

Across the room, the airman in the armchair farts noisily as his head flops on to his shoulder. Stefan picks up a flattened cushion and throws it at him, barking out a swoosh of syllables. Grunting, the airman shifts and opens his eyes, then he sees Vee and jumps to his feet. Without a word, he steps forward and takes hold of her hand pressing it to his lips before Vee can resist. Then he makes the same Germanic head bowing and clicking of heels as Stefan but with more flourish.

He says something unintelligible and then, ‘I delight to meet you, madam.’

Vee frees her hand and grins. ‘Hello.’

Stefan raises his chin and then his voice at the airman, who immediately does the same then torrents of words swish back and forth across the room. Vee sees that she was wrong; Polish sounds nothing like German. This language glides and cracks in an unfamiliar, incomprehensible stream. Not a single word resembles anything English.

‘He is trying to tell you that his name is Piotr Drzewiecki. But everyone here now calls him Double Whiskey and he must get used to it.’

‘Must he? Why?’

‘Because we try to make things easy for our English hosts.’

‘Not everyone can have a name that is idiot-proof.’

Stefan turns back to face her as he realises what she means. He blinks slowly. ‘Your name…’

‘…is Armenian. You were right. My father came to England as a very young man and then he met my mother. Katchatourian might be a mouthful but my father kept the name because it is all that he has left from his homeland.’

‘Which is now in… the Soviet Union?’

‘The town where he was born is in Turkey, I believe. But he washed his hands of the place long ago. People with names like his were treated horribly there.’

Vee surprises herself by how much she has said. Usually, she throws down her surname like a challenge, refusing to excuse or explain, and is ready to pounce when anyone gets it wrong.

Stefan is staring at her with an intensity that is disconcerting. She picks up her cup, draining the tepid tea. Then she looks at her watch but Stefan is quicker.

‘A quarter to two.’

‘Yes.’

‘You have been here only twenty-five minutes. And vis is not much better.’

‘Actually, I’d say that it seems much improved.’

But the window is too misted and dirty to tell whether the weather is getting better or worse.

‘Why not stay here? You have your things.’ Stefan nods at her overnight bag.

‘That’s only in case of real emergencies.’

‘Perhaps if you stay here you will avoid a real emergency. Piotr says no routine take-offs will be allowed for the rest of today.’

Is that what they’d been talking about? There seemed more passion to it than a conversation about the weather. Vee summons her most crystal-cut English voice.

‘Well, ATA authorises me to make my own decisions. So I’ll leave now and get back whilst there’s enough light.’ With a scraping of wood, she stands up. ‘Better not let the engine get too cold.’

Stefan stays seated with his arms on the table and begins to make some other argument for her staying here, but Vee is out of the door before he catches her up.

The mist is most definitely lighter now and Vee enjoys a shiver of smugness that she was right. Her pace slows as she senses Stefan’s broad shadow behind her.

‘Please don’t trouble yourself to come with me.’

‘But you need someone to turn the airscrew.’

‘Do you not have ground staff?’

‘I am very happy to do it myself.’

And perhaps, now she thinks of it, that would be for the best. Someone else here might demand official clearances and maybe even telephone Captain Mills. Which could make things tricky. All being well, she will not have to mention this forced landing at all, just say that she gave Birch a miss due to the nearby sea-fret. That should keep her cross-country record in the clear.

The haze has lightened enough for Vee to see the row of Hurricanes and Spitfires on the far side of the runway. She cannot stop herself asking.

‘You fly fighters?’

Stefan nods. ‘You too?’

‘Oh no. Not yet, at least. I have to get my Wings first.’

‘Soon, then.’

‘Maybe not, after today.’

‘Ach! All pilots get lost in cloud. What do ATA expect, if you have no radio?’

She smiles. He seems so indignant on her behalf.

‘Do you think anyone will tell ATA that I was here?’

‘It is better for you if they do not?’

‘Well, a forced landing doesn’t look very good, does it?’

‘In that case I will make sure there was no Tiger Moth landing here today.’

‘Will you? Thanks awfully.’

Stefan shrugs with one shoulder. ‘It is nothing.’

Briefly, his hand touches her sleeve. ‘Please, stand there a moment.’

He steps closer, scrutinising her face. Vee smells the cinnamon edge of his soap and the leather of his flying jacket beneath the overalls. Her pulse quickens as he pulls a perfectly white handkerchief from his pocket.

‘There is grease. Close your eyes.’

Without thinking, she does as he says and puts her face up to him like a child. Her eyes close. Soft fabric strokes, again and again, at the same spot just below her eyebrow.

‘There.’

Her eyes open and she feels a tug of air as he steps away. His expression has changed; it is serious, embarrassingly so, and there is something in his gaze that seems desperately sad.

She smiles awkwardly. ‘Is it really so perplexing for you to see a woman in a cockpit?’

‘No. Why?’

‘You look at me so oddly, and when you first saw me you seemed…’

‘What?’

‘Shocked.’

‘No. You are wrong. I have nothing against women pilots. The very opposite, in fact…’ She sees his throat move as he swallows. ‘In fact, I…’

He opens his mouth as if to say more but then shakes his head. His skin instantly has a greyish tinge.

Suddenly self-conscious, Vee puts a hand to her forehead to peer down the runway.

‘I think the cloud base has lifted above a thousand now.’

He sighs. ‘You are right.’

They go to the Tiger and Stefan stands beside the cockpit. Vee lowers the parachute pack into the hole in the seat before settling herself on top of it. She takes out the map and once again Stefan leans over it, pointing.

‘Keep dead east until you see the railway track. Then, if the vis is still bad, follow the track north to Rivenhall and land there, see?’

‘Thank you.’ Another unscheduled landing? She would do no such thing. Vee flips the ignition switch. ‘Now, if you wouldn’t mind? The screw?’

Stefan nods and moves off towards the nose.

‘Throttle set.’

‘Throttle set. Contact!’

He pulls the blade with both hands and the propeller blast throws his hair across his eyes. The Tiger’s engine blurts into its sewing-machine patter and Stefan steps back, waiting as Vee tightens the strap across her lap and pulls on her gloves. He is still there, hands in pockets and a twisted look on his face, as she tests the flaps and checks the dials whilst the engine warms.

Perhaps she reminds him of someone he used to know. Maybe someone in Poland. Maybe even another female pilot. A chap that good-looking will have had lots of girls. Although something about Stefan’s drained expression suggests that he does not much want to think about whoever it is that Vee has brought to mind.

Vee gives him a polite wave before steering the Tiger on to the concrete. She throws a final furtive glance as she pushes the throttle lever forward. He does not wave back. The windsock lumbers up in the slight breeze from the sea and the Tiger hops easily, as it always does, into the air.

Almost as soon as the wheels are released from the pull of the ground, the atmosphere around the bi-plane dilutes into weak sunlight. Vee circles on to an easterly bearing by crossing and re-crossing the stripe of listless waves along the estuary’s edge. As she gains height, a slice of clear air opens between the ground fog and a high ceiling of cloud. To the east, a railway track scores through drab fields. Ahead on the horizon is the brown smudge of London. Then as Vee looks back at the receding aerodrome her heart jumps. Illuminated by the flare path, Stefan is still there, hands in pockets, shoulders hunched. And he is still looking her way.

Posen, Greater German Reich

Thursday 1 April

Ewa can tell by the way her father is frying eggs that he is in a bad mood. The fat is too hot and it spits grease over the stove top, burning black bubbles into the egg-whites. He looks over his shoulder at her, glowering. Beer froth flecks his grey moustache.

‘Lie-in?’

‘Hardly.’

‘You know how much there is to do. And another Schutzstaffel officer is arriving this morning.’

‘Without any notice? They’ve got a nerve.’

Her father’s eyes dart. ‘Keep it down, Maus.’

Ewa clatters dried-up dishes in the sink and bangs the half-full coffee pot back on to the stove. ‘Where will we put him? In the gable room?’

‘No, he is an SS-Obersturmführer. He should go in the oak-bed room.’

Ewa nods. At least the attic room next to her own will stay empty a little longer. Panic sometimes waves through her when she thinks of those few thin centimetres of plaster and wood that separate her secret drawer from the head of a snoring officer of the Reich.

Overcooked eggs bounce as her father tips them on to a cracked plate. He balances it on a pile of papers on the dresser and, still standing, chops the rubbery eggs with a spoon. Ewa leans the base of her spine against the sink and folds her arms.

‘And will we charge extra for the bigger room?’

Her father shakes his head as he pokes a slice of stale black bread into the hardened yolk. ‘A flat rate was agreed. Let’s just be glad of the business.’

‘And the extra work?’

‘Yes, why not? A new lodger will make up for the empty dining room.’

‘What else did you expect, Papa, when we put the “Germans Only” sign on the front door?’

His hand with the black bread halts mid-air as he glares. Ewa has gone too far. She knows that he feels uneasy at the extent of their collaboration with the occupiers. But whereas Ewa can justify her own politeness to the lodgers as a cover for her secret resistance, her father, Oskar, must make himself believe that he has no alternative. The German invasion was inevitable, he argues, because the Republic of Poland was so weak. The country existed only for twenty years before dissolving again inside the borders of its mighty neighbours. How can he be a traitor to a state so flimsy and one that is no more?

Ewa suspects that her father was, in part, relieved when the Wehrmacht marched into Poznań and promptly changed all of the town signs to Posen. The city immediately began to look and feel a bit more like it did in Oskar Hartman’s youth. And no longer did he feel a twinge of embarrassment about his German name, or have to sing his favourite Christmas carols in private.

Although he would never admit it to her, Ewa wonders if her father prefers to be an actual German rather than a German-speaking Pole. But Oskar was born and raised in the city when it was part of Germany and he even fought unswervingly for the Kaiser throughout the World War. Ewa suspects that her father does not himself know where his loyalties really lie and she cannot help picking at his discomfort like a half-healed scab.

‘Enough, Eva.’

The sound of the wrong name in his mouth, with its hard German E, makes Ewa want to rip the scab right off.

‘We should never have gone on the DV List.’

‘Not again, Eva. And quietly.’

‘I’m not Eva. I’m sick of that name.’

But in order to secure their place in Category One of the Deutsche Volksliste and so be allowed to continue their business in the guest house after the occupiers arrived, Herr Hartman had sworn that the name on his daughter’s birth certificate was not his choice. In 1919, when she was born, the newly appointed Polish officials who filled out her birth certificate had automatically changed her German name Eva into the Polish Ewa. But at home, Oskar insisted convincingly to the sympathetic SS-Scharführer, his daughter was always called Eva.

Oskar brings his empty plate to the sink and hisses. ‘If you were still Ewa we would not be living in this guest house any more. Some smug settler would be standing where I am, cooking herrings for every meal and speaking German with a Russian accent. Imagine that!’

She shrugs with one shoulder but knows he is right. They had no real choice about the Volksliste. Their life, if they had been categorised as Poles then evicted and perhaps sent west to the Alt Reich as forced labourers, is unimaginable. And how could she be any use to the Polish underground army, the AK, if she were slaving in a German factory somewhere wearing a purple star with a P on it?

Ewa pours half-warm coffee and raises the bowl to her lips to hide her defeat. It is pitiful really, to be arguing like this with her father. She sounds as if she is fifteen not twenty-three. But there is comfort in a bad temper; it stops her thinking about the life she might have had without the war.

‘I am sorry, Papa. I will put the best sheets on the oak-bed.’

‘Good, Maus.’ He turns on the tap. ‘I know it is hard for you to be running everything, especially with the guests we now have…’ He puts his hand over hers and squeezes it. ‘I could not manage to keep the guest house going without you.’

She feels an unexpected prickling at the back of her nose and leans herself against her father’s warm bulk. His cheek bristles against her forehead.

‘I’m glad to do it, Papa. And they do not give me any trouble really.’

She stands back and pulls a speck of yolk from the tail of his moustache.

He nods and keeps his voice low. ‘At least I am too old to be called up, unlike some who chose the DV List. You will not have to worry about being here on your own.’

In the yard, a door bangs and Ewa’s heart jumps. Could that be the new lodger? She was not telling her father the entire truth about the officers. Most of them, if not polite, at least keep their hands to themselves. But a few do not. An aloof officer in the oak-room would be a godsend. She peers through the net curtain into the yard. But it is just Scharführer Feldman pulling his braces over his vest as he comes out of the guest house’s toilet block.

‘I know, Papa. I shall go and clear the breakfast things. They have all finished now, I think.’

And when Ewa gets to the dining room with her tray, she sees that the officers have indeed all left, apart from one. His back is to her. It is the same grey-green jacket that they all wear but she knows instantly that she has not seen this one before.

She has learnt to speak first. ‘Heil Hitler!’

He turns. His hair, dark blond, is slicked back as though wet through. He smiles and Ewa sees that he is quite extraordinarily good-looking.

‘Good morning, Fräulein Hartman.’ He stubs out his cigarette and stands, giving only a quick nod of the head. ‘SS-Obersturmführer Beck. Delighted to meet you.’

It is good of him to spare her the full Heil Hitler rigmarole.

‘Thank you, Obersturmführer. You are our new guest, I take it?’

‘I am.’

‘So sorry I have kept you waiting. You should have rung the bell for me or for my father.’

‘The front door was open and I did not like to trouble you in the kitchen.’

His smile is friendly and he does not seem to have the striding confidence that oozes from most of the others. Ewa always has to fight her instinct to be cool and sullen towards the occupiers because she knows that friendliness is the insurgent’s best disguise. And she tries not to actually like any of them. But she can see that with this one that could be hard.

‘Thank you, Obersturmführer, you are very kind. Would you like breakfast now? I have not quite finished preparing your room.’

‘Just a coffee, if you please.’

‘Certainly. I have made a fresh pot.’

In fact, the dregs from the coffee pot have been stewing on the stove for a good while but Ewa pours them into one of the best Rosenthal cups. She blinks as she remembers Beck greeting her by her name. How did he know that she wasn’t just a girl who had come in to help with the breakfasts? And the way he had slipped straight into the dining room from the street seemed, if not fishy, then at least a little surprising. But if he has been sent here with a purpose, to watch her, he would surely have been more careful with his instant greeting. Perhaps he simply recognised her from descriptions given him by the other lodgers.

Ewa puts the cup with its pale pink roses and muddy coffee on the tablecloth in front of Beck. He has unbuttoned his jacket. The beige shirt beneath seems to cling to his skin as if damp. Ewa tries not to look as she clears the other tables. Some of the checked napkins are already tightly rolled inside their individual rings and stacked beneath the mirror on the side-board. Other linen squares have been left crumpled on the tables with a high-handed assumption that Ewa will know to which officer’s ring each belongs. She certainly knows the rudest officers by the way that they leave their napkins.

Obersturmführer Beck sips from the porcelain cup. ‘Thank you for this, Fräulein. Such an improvement on barracks’ coffee.’

Ewa keeps a clear smile even though she knows he is lying. ‘You have been staying at the Castle?’

‘Yes. And I’m delighted that my request to move here has been approved.’

‘You requested us specially?’

‘Oh yes, everyone says that this is the most superior guest house in the city.’

Now he is definitely lying but Ewa’s smile broadens. ‘You flatter us, Obersturmführer.’

‘So please forgive me for arriving at breakfast-time, but after rising early for my swim, I could not quite face crossing town again to go back to the bunk-room.’

Ewa stacks the remaining rolled napkins on the side-board. A swimmer. That would account for his wet hair, and perhaps, his muscled shoulders.

‘You like to swim, Obersturmführer?’

‘Indeed.’

‘At the new pool?’

‘You know it? An excellent amenity for the city. Have you swum there yourself?’

Her smile does not waver as she shakes her head. ‘Not yet, but I hear it is very fine.’

In fact, the thought of swimming at the indoor pool turns her stomach. For although the pool is new, the building that houses it is not. Who is to say that St Adalbert’s might not be next to go the same way? A church could be turned into a gymnasium as easily as the city’s grand synagogue has become an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

Beck clinks cup to saucer. ‘It is such a modern sports facility. The water is kept at a perfect temperature for athletic swimming but the air is always warm. If you wish, I could arrange for you to swim there privately, after public hours.’

His finger strokes the delicate handle of the cup as he looks at her and warmth rises in Ewa’s neck. For once, the heat does not come from the effort of suppressing her resentment to the occupiers.

‘That would be delightful, Obersturmführer, as soon as I have some time to spare. Do you swim often?’

‘Every day, if I can. The pool is so convenient for the library.’

‘The library?’

‘Indeed. That is where I am working.’ He pauses and runs a hand over his wet hair, smiling at her confusion. He taps a yellow packet on the tablecloth. ‘Do you mind?’

Ewa indicates for him to go ahead and smoke. Then he holds the cigarette pack out and her heart skips. Mokri Extra Strength – the same type that Stefan always had in his pocket.

Beck gestures to the chair beside him at the table. ‘Do you have time now, for a smoke?’

‘All right. Thank you.’ She makes herself smile as she goes forward to take a cigarette. Why not be friendly to this new one? At least, at first.

Beck clicks his lighter and holds the tall flame to her face.

Ewa sucks on the smoke and hitches up her skirt a little as she sits. ‘So, you are a scholar, Obersturmführer?’

He sits back and rests an elbow on the table, a curl of smoke rising from the cigarette in his hand.

‘Ah, before the war that was my dream. But at least my linguistics work now has a practical application.’

Ewa blows out a plume of nicotine fumes and tries not to seem over-interested. ‘How so?’

‘I have been placed in charge of the re-naming project.’

She smiles and puts her head to one side. ‘Changing the street names, do you mean?’

‘Not just streets: I have been charged with finding the proper German name for every place on the map of the whole of the Warthe region, even down to the lowliest hamlets and narrowest alleyways.’

‘Goodness! That sounds like a big job.’

‘It is. I could spend every night in the library and still not get through all of the research that should be done.’

The cigarette hovers close to Ewa’s lips. She fixes a steady gaze on his light grey eyes. ‘It can’t be easy to find the old German name for every place.’

‘As long as I have sufficient time with the antique maps and land documents I shall do it. Although not all of the old names are appropriate.’

‘Really?’

‘The street that leads to the new swimming pool, for example.’

Zydowka Street, he means.

Ewa taps the cigarette against the ash tray. ‘I am too young to remember what it was called when our city was part of Prussia.’

‘Indeed! But the name was the same. Jüden Strasse. So we couldn’t have that name back, could we?’

‘No. I should think not!’

She laughs and tries not to sound awkward.

He smiles. ‘I think that the new name, Becken Strasse, suggests the proximity of an engineered water feature. A pure coincidence that my own name will form part of the new street sign.’

He winks but seems to poke fun at himself and Ewa laughs without having to fake it.

‘What a fascinating and important job!’

He pulls out his chair at an angle from the table and stretches out his legs, one ankle crossed over the other.

‘Oh, it can sometimes be tedious. I have only been working here for a month but already there are disagreements between the army and the Post Office about maps and addresses.’

Ewa takes a long drag on her cigarette and tries to place his origins from his voice but his German is accentless. She realises, as she listens to him talk, how gentle and melodious the language can sound.

‘Where are you from, Obersturmführer?’

‘Where do you think?’

‘Somewhere with a very pure dialect.’ She shrugs. ‘Hanover, perhaps?’

‘Good try.’ He nods, grinning. ‘Do you want to guess again?’

‘Erm… Dortmund?’

‘Let us not end the game too quickly. Why not have one guess on each day that I am here in your lovely guest house? But I doubt that you will get it right.’

Ewa’s foot bounces as she crosses her legs. ‘I might surprise you!’

With a jolt, she realises that her guard has fallen. For a few moments she has been talking to Beck without any thought to his uniform, or to the threat he might pose.

‘Well, Obersturmführer, I look forward to my daily quiz, and to providing you with Hartman hospitality.’

She stands and goes to the side-board for the spare napkin rings from the drawer then places them on the table in front of Beck. Golden hairs bristle on the back of his neck above his jacket’s velvety green collar.

‘Would you like to choose one? We launder the napkins weekly so each officer keeps his own in a personal ring.’

There are three distinctive designs; one made from horn and carved with stags’ heads, one painted with mountain flowers, the other an unadorned pewter band. Beck surprises her by picking the plainest.

‘Good choice, Obersturmführer.’

‘Plain as a wedding band.’

He smiles and holds Ewa’s gaze as she rolls a pink linen napkin. Only the pat of her heartbeat tells her that she is holding her breath.

As she turns away to replace the unused rings in the drawer, Ewa composes her face. On a few occasions, she has had to make an effort of will not to take a fancy to one of the officers billeted in the guest house. Her friendly, sometimes flirty, act must not become real feeling or her cover could be compromised entirely. Besides, although she may not dislike every officer who stays under her roof, she detests what they stand for.

But her instincts have never before been tested quite like this. Because at this moment, Ewa can think of nothing she would like better than to be inside the former synagogue on Becken Strasse watching Obersturmführer Beck climb, dripping, out of the pool.

She sets her face into a tight smile before she turns. ‘Could I get you another coffee whilst I prepare your room?’

‘No, thank you. And please do not go to any great trouble.’

‘Oh, it is no trouble, just a little dusting and fresh sheets.’

She nods, as brisk and airy as she can manage then leaves the room.

But as she creaks up the stairs, a dull, familiar wash of guilt tugs at each step. She passes the door to the oak-bedroom and continues to the next flight of stairs up to her low-ceilinged bedroom amongst the eaves. She locks the door behind her then sinks down on to the rug.

It is not fair. Why can she not admire a good-looking man without the pleasant sensation of lust being doused by guilt? Saints in heaven, it has been three years since she last heard from Stefan. Three of her best years, wasted. It would be better if she knew for sure that he is definitely dead. Because, as it is, the whole of the rest of her life might have to be lived in the shadow of a Stefan-shaped question mark.

Is the rest of her youth to slip by without any sort of love? She cannot save herself for a ghost. If things had been the other way around, Stefan would have found himself another lover by now. For all Ewa knows, he maybe already has. She sits unmoving on the floor, willing herself to imagine Stefan with an imaginary girl in another country. But tears prickle her sinuses. She shakes her head. Three years is long enough, damn it. Somehow, she must rid him from her heart.

Ewa sniffs and then pushes herself softly on to the glossy, uneven floorboards. With her face pressed against the wardrobe, she reaches both hands beneath it until she can feel the two clips. Bracing her arms to catch the weight, she swivels the clips and lowers out a square tray a little bigger than a shoe box. Soundlessly, she carries the secret drawer to her bed and places it on the eiderdown.

The few bits of old underwear on the top would fool no one but she cannot bring herself to leave the contents entirely undisguised. She lifts the noiseless typewriter on to the bed along with the sheaf of closely typed papers – numbers, words, dots and dashes that she has copied from the agents’ scribbled notes and blurry photographs without a clear understanding of what any of it means. The sheaf is growing. She must let the liaison girl know that she needs to make a drop.

Beneath the typing is a little pile of opened brown envelopes. The sight of his handwriting always makes her catch her breath, as if Stefan himself has been hiding beneath the wardrobe. She does not really need to conceal his letters so closely. Even in the Reich, it is not a crime to have had a fiancé who served in the armed forces of the extinct Republic of Poland. It is just that until now, Ewa has not been able to bear the thought of anyone else reading Stefan’s words of love.

But the words are fading. And although Ewa can recall her emotions from the time when the letters arrived, she no longer feels them very much. She pulls the letter from the bottom of the pile. It is the one that came just before the first Christmas of the war when she had not seen nor heard from Stefan since the sultry summer morning on which he had boarded a Warsaw train crammed with troops in brown uniforms. Their last kiss had been so fierce that it left a bruise inside her lip.

And so, the first sight of an envelope with her name written in his hand threw Ewa into a swirl of emotions. As she tore it open, joy washed through her. Stefan was alive, and entirely himself; his words proved that. ‘I have to admit,’ he wrote, ‘that the Karas crashed on our very first sortie against the Soviets, and it was brought down embarrassingly, not by an enemy bullet but by a slight mechanical malfunction. Then, I and my co-pilot walked in so completely the wrong direction that we soon bumped into a charming Red Army captain who seemed rather embarrassed to lock us up.’ Even now, Ewa hears his voice in the words and cannot help but smile.

Stefan made the prisoner of war camp sound bearable, impressive, even. The ancient monastery citadel where he was kept is so vivid in Ewa’s mind that she sometimes forgets that she has never actually seen the towering perimeter walls orthe bunks piled six high inside the magnificent domed church. Stefan told her that he slept in the best spot at the very top of the bunk-stack with a clear view of the coloured frescoes of the saints. This position also spared him, as he says: ‘…the unpleasantness endured by those on the lower bunks who are dampened by a constant trickle down the walls of moisture from the breath of hundreds of men (as well as the moisture created by those men unwilling to climb down to the bucket during the night!).’