6,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

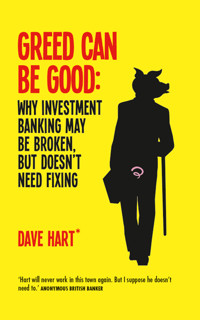

The real problem is that when we disclose the size of our losses, the market - which is to say, our major institutional shareholders - will expect top management to take responsibility. That means me. They might even expect me to fall on my sword. I'm not a falling on my sword type. Why should I? I genuinely have very little understanding of anything that goes on here, so why expect me to take responsibility for it?' The fourth of David Charters' hilarious financial satires set in the City, Where Egos Dare charts Dave Hart's navigation through the 2008 credit crunch and ensuing economic crisis as Chairman of Grossbank, the largest investment bank in the world. When a rogue trader is found at the heart of Grossbank and the company loses millions of pounds, can Dave Hart take on a stockmarket in the middle of financial meltdown and win?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 248

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Ähnliche

WHERE EGOS DARE

DAVID CHARTERS

First published 2009 by Elliott and Thompson Limited

27 John Street, London WC1N 2BX

www.eandtbooks.com

ISBN: 978-1-9040-2777-5

Copyright © David Charters 2009

This edition published in 2009

The right of the authors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed in the UK by CPI Group

For Digger

Author’s Note & Acknowledgements

IT HAD to be someone’s fault. The worst financial crisis of our lifetime did not just happen by itself. And if we’re going to blame someone, why not Dave Hart?

As a spectator watching the crisis unfold, I felt that truth really was stranger than fiction, and at the same time quite inspirational. I’ve tried to capture once again the extremes, the excesses and the absurdity of the Square Mile during one of the most turbulent times in its history. And as ever I’m grateful to a number of people who provided help and input: Lorne Forsyth, Jane Miller, Joanna Rice, Adam Shutkever, my son Mark, my daughter Anna and my sister Margaret all gave generously of their time. And of course there’s Two Livers, without whom none of this would be possible…

I THINK I’m going mad.

I know I can’t be dead. I know because it’s hot as hell, and that simply does not compute. How could I have died and gone to hell? It’s impossible. Hell is for other people. In fact hell is other people. It’s certainly not for me.

There’s a hot wind blowing over me like a giant hairdryer. I’m lying on my back, being dragged across a surface that alternates between smooth and rough, and my body is aching. The whole of my right side is hurting, as if my ribs are broken. Maybe they are. The sun – that is, I suppose it’s the sun – is burning my face and I’m keeping my eyes tightly closed.

But at least I can’t be dead. That’s important. Because where would the world be without me?

My mouth is parched and my lips feel painful and cracked. I slide and lurch forward a few more yards. Whatever it is I’m lying on is being pulled slowly across the ground. Somewhere nearby I hear a soft sigh that’s feminine, wonderful – a weak-strong moan of someone exhausted but determined.

That’s when the memories come back.

I was flying home to London from a business trip to Africa. I was in a private jet – a Gulfstream 5, my personal favourite – about to sip champagne and toast success when there was an explosion. I recall the pilot’s voice frantically calling in a Mayday, then another loud bang and everything is hazy.

Until now. Now the memories are flooding back.

I’m Dave Hart.

Knowing my name is important – at least, it is for me. With that comes a whole avalanche of other memories. I’m a banker. At the tender age of forty, I became chairman of the Erste Frankfurter Grossbank, one of the largest financial institutions in the world, and took the whole giant organisation into overdrive. I’ve achieved things, made things happen, financed the unfinanceable, poured money into projects in Africa that no one would touch, changed the world. I’ve done things in the world of business that no other human being ever has. And some that no other human being would ever want to. Either way, I’m a finance rock star.

I’d been visiting Lubumbashi, a godforsaken dump of a place where Grossbank’s New Start Plan for Africa – an investment plan to acquire assets and develop them in return for introducing proper governance and democratic institutions – was reshaping a nation. I was reshaping a nation. That sort of thing appeals to me. I like changing things, upsetting people, pissing them off. And I like to think big. If you’re going to bother to think, it’s the only way to go. Only this time someone got really pissed off. Pissed off enough to fire a rocket up the arse of my G5.

There was someone with me. Someone beautiful. An intelligent blonde. Yes, really. Funny too and sexy as hell. And she could drink.

Two Livers.

Laura ‘Two Livers’ MacKay, my head of corporates at Grossbank, my right-hand woman, key business winner, planner, strategist, possessor of a brain the size of a planet and a body to die for, was with me when the plane crashed.

Two Livers is different from any woman I’ve ever known, and yes, I’ve known a few. When God made blondes, I truly believe he took all of their brains and gave them to this one woman. In my rare moments of lucidity I’ll admit – privately – that most of my success I owe to her.

She is also my lover.

‘Aaaaaagh …’ A woman’s voice. Weaker now. I’m not being pulled forward any more. My hand slips from the side of what I guess is a makeshift stretcher and touches hot sand. Desert sand. I’ve been pulled across the desert. By her. I feel the end of the stretcher slowly being lowered to the ground, gently, so that I’m resting on the sand, hot through the canvas.

Damn. I guess it means I have to get up.

I open one eye cautiously. No need to worry. I can see her kneeling a few yards from me, her head slumped forward, her beautiful blonde hair falling across her face, the tattered remains of what was once a beautiful Chanel dress hanging loosely over her perfect body. She’s barefoot. Walking barefoot on the hot sand. Like a slave girl. The fantasy part of my brain whirrs into action. It’s like a scene from a movie. If I weren’t in so much pain I’d think about jumping her right now. Although having sex on a dune is always a bad idea. Sand gets in all the wrong places.

My own clothes are just as badly torn, my shirt hanging in shreds around me. I ease myself up painfully on to one elbow and watch as she slowly rolls forward until her head touches the sand. She’s instinctively curled into a tight ball, exhausted, vulnerable, her last reserves gone.

Bugger. Now I’ll have to get up and start walking.

I pull myself over and slowly stand up. I’ve certainly cracked several ribs, and I feel weak and slightly dizzy. I’d kill for a drink. In fact several, plus a decent meal and maybe a sharp, reviving line of white powder. But at least I’m alive. The sun is unreasonably hot, and I stare in wonder at the tracks left in the sand, extending far away into the distance. She’s been pulling me for miles, for hours, through the heat of the desert, on a makeshift stretcher made out of two twisted metal poles and a length of canvas. Why would an investment banker do that? Would any banker truly rescue their boss, if they had the choice not to and no one would ever find out? How much more would Two Livers stand to make each year without me top-slicing the bonus pool?

I walk over to her and crouch down beside her, gently stroking her hair. She’s gone, dead to the world. I put my hands under her shoulders and struggle to pull her on to the stretcher. It’s an effort, but once she’s there I pick up the end and prepare to walk forwards, dragging her in the same direction she was pulling me.

Damn, it’s hard. She may be delightfully slim, but to me in this heat she feels heavy. Forget heroics. This is no fun at all. After a couple of paces I ease her back on to the ground. I don’t know if I’m exhausted or lazy, but there’s no way I’m dragging her across the desert. I stare into the distance. It looks the same in each direction: just miles of undulating dunes.

I analyse things the way that only a senior investment banker can. This is a truly desperate, life-threatening situation. It’s not like the ordinary, everyday problems I have to endure in London, like not getting my favourite table for an early evening martini at Dukes Hotel, or getting stuck in traffic on my way to see Fluffy and Thumper from the Pussycat Club for a private performance. I could actually die. I could really fucking die!

I look at Two Livers, exhausted and unconscious from her ordeal. Damn. Two of us certainly won’t make it, not with me pulling anyway. For both our sakes I need to leave her here – obviously after first checking she’s comfortable – and then head off by myself to fetch help. I know I’m fond of her and all that, but it’s in both our interests. Honestly. In fact it’s because I care for her that I have to leave her now. I’m doing this for her.

Phew, that was easy.

Having taken my decision, I start to head off by myself, but I’ve only gone a few paces when I seem to hear a strange sound. Perhaps I’m imagining it, but I’d swear I can hear a tacka-tacka-tacka noise. Maybe it’s just in my head. Fuck it. Must be the heat. Or the drugs. What have I been using lately? Not much, travelling in Africa. In fact I’ve been remarkably clean. I shake my head to clear it and prepare to set off once more in search of salvation – for us both, of course.

That’s when the helicopter appears over the nearest ridge of sand.

I LOVE press conferences. Something about standing in front of the world’s media creating your own truth, your own version of reality, appeals to my vanity. Whatever you say, it will be printed, quoted, shown on live TV, supported by photographs and film and captions and ‘experts’ who may disagree with you but by their very presence validate your existence. It means I’m alive, and that is very important to me.

We’re in Lubumbashi, the armpit of Africa, in what passes for a conference room in the Foreign Ministry. I’ve had my side strapped up by a Belgian doctor – yes, I’ve cracked a few ribs and I’m dehydrated, but so what? In a month or so I’ll be right as rain, and the dehydration I’ll get to work on right after the press conference.

They’ve leant me clothes – a safari suit that gives me an Indiana Jones look – and the British ambassador, a short, stocky man with whisky-flushed cheeks and a permanent sheen of perspiration, is sitting beside me on the podium, next to the helicopter pilot who found me. Thirty or forty journalists and cameramen are crowding the room. Apparently I’m a worldwide news sensation.

Oh yes, and there’s Two Livers. Well, she’s not exactly here. She hasn’t come round yet. They’ve got her on a drip at the local hospital, trying to revive her slowly. It seems to have taken a lot more out of her than it did me. Funny that. Must be a woman thing.

The helicopter pilot is talking; a young Frenchman who looks remarkably cool and handsome and could easily outshine me if he wasn’t so utterly impressed by my courage.

‘We located the crash site at dawn. We landed and found no survivors. Both pilots were dead.’

Damn. They were good men. Bringing the plane down at all was amazing. Presumably they had wives, kids, the whole thing. I wonder if this counts as war risk so our insurers pick up the tab for compensation. Either way I’d better get someone looking into it. Better be seen to do the right thing.

‘We could see that someone ’ad survived, because the remains of a fire were there. And the body of a wild dog.’ A wild dog? Shit. Where did that come from? ‘It must ’ave been part of a pack that attacked the survivors. At this time of year they are desperate. They will attack large animals, cattle, game, even people. But the dogs ’ad been fought off and one was lying dead, with a sharp piece of metal from the wreck driven through its ’eart.’ Damn. I certainly never fought off a pack of wild dogs. At least I don’t think I did. He’s looking at me, his eyes full of hero worship. He’s right. Pull yourself together, Hart. Obviously I must have fought them off. Well, you would, wouldn’t you? They must be worse than bankers at bonus time. Fight them off or they’ll strip you to the bone. The pilot’s continuing: ‘Then we spotted a trail. Footprints and the tracks of what could only be a stretcher. We followed the trail across the desert from the crash site. Monsieur ’art dragged Miss MacKay for seven miles in temperatures of forty-five degrees.’

At this they stop scribbling and burst into a round of spontaneous applause. Cameras flash and my moment of supreme heroism is recorded to be made real and permanent in tomorrow’s press.

‘Mr Hart, Martin Joyce, Reuters. Does this dreadful episode affect your commitment to Africa and to Grossbank’s New Start Plan for Africa?’

I put on my serious, statesmanlike face. I have to, because otherwise I’d grin. I spent an hour this morning on the phone to my PR adviser at Ball Taittinger, London’s – and possibly the world’s – leading spinmeister. I call him the Silver Fox, after his silver-grey, sixty-something, urbane appearance and innate sense of cunning. A lesser man would have been sitting at Two Livers’ bedside, holding her hand and swooning over her, but I know how important first impressions are, and I needed to get this story right. It runs to the heart of who I am, and what can be more important than that?

Before I answer, I take a sip from a glass of water beside me and wince theatrically from the supposed pain. Then a deep breath and a determined look, and I’m away. ‘Quite the opposite. It shows more than ever the need for us all to reaffirm our commitment, redouble our efforts and ensure that lasting change continues – whatever the cost to those of us at the sharp end. Right now, even as I speak, Laura MacKay, the head of corporates at Grossbank, is lying in a hospital bed less than half a mile away on a life-support machine.’ Actually it’s a saline drip, but I’ve never been a great one for detail. ‘I’m going to say to you what I know she would say if she were here. We’re here to stay. We won’t be intimidated. We won’t be put off. I am personally committed to this programme, and I lead from the front.’ In other words, I’m a saint as well as a hero. Got that?

A huge hubbub of voices and the polite conventions of the press conference very nearly break down in the rush to get in follow-up questions. Christ, I’m good.

HEATHROW IS grey, wet and windy and, by comparison with Lubumbashi, just plain dull. It’s taken us a week to get back, because Two Livers was too weak to travel and I had to stay loyally by her side. Right now she’s being pulled along on a trolley by a medical team, theatrically orchestrated by the Silver Fox, still heavily sedated while her body heals after her ordeal. I’m walking beside her, my hand in hers even though she’s not actually conscious, while press photographers snap away and cameras roll.

‘No, I’m sorry, no further comment. Now is a time for healing and recovery. Please give us some privacy. Thank you.’

It’s all bollocks, of course, but you still have to get it right.

Once we’re out of sight of the press, Two Livers goes one way to a private ambulance, while I’m met by Tom, my personal driver, standing tall and imposing next to the Grossbank Bentley that I’m chauffeured around in. For once the Bentley’s unaccompanied by any other vehicles. I’ve dismissed my private security guards, disregarding all advice to the contrary. If I can survive an air crash in the desert and walk away, then I’m clearly not meant to die. God wants Dave Hart to live, so who needs security?

It’s not that I’m religious – the only thing I truly believe in is me – but I do have a sense of destiny. I’m here for a purpose, and that purpose is not just drinking and screwing and doing drugs.

Having said that, on the way in from the airport I call Sabine, twenty-five, from Belgium, and Charlotte, twenty-three, from Boston, and arrange to have a party. A private party to celebrate my homecoming. Just the three of us.

EVEN GOD took one day off, so I figure I can too. Bad habits die hard, and after twenty-four hours I’m totally wasted, my nose is semi-permanently running and even the Viagra isn’t working any more. How much abuse can a body take? Especially with three cracked ribs. The girls are fantastic, but I need to escape back to work.

My return to the Grossbank building is everything you would expect. It’s like the second coming. God has arrived. Or is it Elvis? Must be Elvis, because cheering traders stand up at their workstations on the trading floor to applaud as I limp purposefully towards my huge corner office. I have a strange feeling of déjà vu – haven’t I done this before? Maria, my faithful secretary, plump, half-German, mid forties and a Grossbank lifer, is waiting to show me in and welcome me back. I’ve always thought of her as Grossbank’s answer to Brunhilde, but this time she actually puts her arms around me and gives me a gentle hug.

‘Welcome back, Mr Hart. Welcome home. And no more adventures, please.’

I give her a devil-may-care smile and disappear into my office, where I take my jacket off, close the blinds, put my feet on the desk and feel instantly, indescribably bored.

I turn to the computer. ‘You have 1,741 unread emails.’ I click on ‘Select All’ and delete them. Who the hell are these people who think they can impose their garbage on me – management reports, meeting notes, requests for authorisation of this and that? It’s so dull I can almost feel a coma coming on. This is definitely not what I’m here for.

I flick on the intercom. ‘Maria, any messages? I mean important ones?’

I really didn’t need to add that. Maria understands. I’m not interested in bullshit messages of congratulations from competitors – or other investment bankers who think they might be in the same league as me – and I am especially uninterested in anything from Wendy, my ex-wife, who will have been rubbing her hands in anticipation at getting hold of some of my estate, though I do tell Maria to send round a container-load of toys from Harrods. I may not make it to see Samantha, our five-year-old, for a while, given all of my various commitments and the time I need for healing, but I don’t want her to think I don’t love her.

‘Maria, send in Paul Ryan, would you?’

Paul is my head of markets. He runs the traders who swing the Grossbank balance sheet around, taking positions, buying and selling stocks and bonds, foreign exchange, commodities, anything where an elephant the size of Grossbank can move markets, squeeze out the little guys and profit. If Two Livers is my right hand, Paul is my left. I owe a huge amount of my success to him and, more importantly, I feel I can trust him. Not too far, but at least some considerable way. So long as I control his bonus, which I ensure is also considerable.

What I particularly like about Paul is the fact that he’s gay. This is important, because he’s incredibly good-looking, always immaculately turned out, and if he wasn’t a banker he could be a film star or a male model. As a result he’s the perfect companion: a pussy magnet who has no interest in women. I enjoy business trips with Paul, and I’m going to plan a few now.

The door opens and he bounds in. ‘Dave, the jungle drums weren’t working this morning – I had no idea you were back in the office. I thought you’d be taking it easy.’ He’s full of energy and enthusiasm, bright-eyed probably from having just done a couple of lines of coke, which would explain why he wasn’t here to brown-nose when I first arrived. But he’s making up for it now. He gives me a hug and I have to gently ease him away before he cracks my ribs again.

‘Easy, big guy. I’ve got three cracked ribs and the reason I’m back in the office is that I need a rest. Couldn’t keep up the pace at home.’

He grins. He understands. ‘Dave, you’re a hero. A real hero. The way you saved Two Livers, fought off a pack of wild dogs, dragged her across the desert in that heat – it’s unimaginable.’

He’s right. It is unimaginable. Anyone who knows me at all can’t imagine it. I give a semi-self-deprecating smile. ‘Don’t believe everything you read in the press.’

He says nothing, which troubles me. Clearly he doesn’t believe a word of it. In fact the whole vibe I’m getting is scepticism tinged with hostility. Mind you, if he was that gullible I’d never have hired him.

This is the great conundrum of investment banking. You need to hire damned good people, and you need them to be sharp and smart and aggressive and freethinking. Pussycats need not apply. But then what happens if they’re freethinking about you? It’s called evolution. They don’t just eat your lunch. Eventually they eat you.

Forget the business trips. I’d better start keeping an eye on Paul.

My eyes glaze over as he updates me on what’s been happening in the business: new hires, new fires, new clients, new business and new offices being opened as the Grossbank empire spreads ever wider. In other words, all the tedious detail that keeps people busy if they spend their lives below thirty thousand feet.

He tells me that our balance sheet is now so bloated that it exceeds the gross domestic product of Germany. That’s right. The value of all the goods and services produced and consumed last year by some eighty-two million hard-working people in the Federal Republic of Germany has now been officially exceeded by the financial assets and liabilities of a single firm. There are seventy-five thousand Grossbank employees worldwide, but actually fewer than fifty of us who matter. They’re the ones who call the shots. And the ones who actually understand what’s going on? A tiny handful, if that, including Paul and Two Livers, but certainly not including me, and even then there’s no way any one brain can comprehend all the moving parts – the risks, the complexities, the vulnerabilities – of something so huge. It makes me want to yawn. Thank God Paul’s there to handle it.

‘Paul, I think I’m having a crisis.’

He stops in full flow and stares at me. ‘What sort of crisis? A real one? Or …’ He taps the side of his head. ‘You know. The other sort.’

Only a true friend could say this to me. The implication in his question is that I might be suffering from something more serious than a hangover or an excess of nose candy. He’s suggesting I might actually have something wrong with me. In my head. Any other employee would have been instantly on Death Row, black-bagged by a couple of security guards and walked out of the building.

But Paul’s a friend. I think.

‘I’m bored.’ As if to demonstrate how bored I am, I get up and pace uselessly around the office. ‘This all seems so … worthless. Everything we do. All of it’s bullshit.’

He shrugs and tries to look sympathetic. ‘But, Dave, it’s so well paid. Think of the money.’

‘I know. You’re right. But I need to find a way of keeping engaged. The whole Africa thing was exciting to start with, but now it just seems so yesterday.’

‘But the firm’s making a ton of money out there. Don’t knock it.’

‘I know. But other people can handle it now. It doesn’t need me any more.’

There’s a long, awkward silence. I wonder if he thinks anything needs me any more. Or ever really did. Maybe I’ve achieved the ultimate goal of any boss – I’ve made myself utterly redundant.

‘It’s scary, Paul.’

‘Scary?’

‘Scary. I feel as if my life is futile, worthless and insignificant. Yet I make millions. Tens of millions. In fact I made more in a single year last year than I once thought I’d ever make in my lifetime. How can that be?’

This really is scary. With what I’m making, and what the firm has actually achieved, I ought to be really happy. In fact travelling around Africa with Two Livers I was. So what’s happened?

‘Dave, if you ask me, you just need a new challenge. Or maybe a change of scene. Have you thought about doing something outside banking? Not full-time, obviously, but why don’t you look at getting involved with something charitable or philanthropic? Something that would take your mind off things here, just for a while?’

Gotcha, you bastard. He really is after my job. As if I wouldn’t see it. ‘You may be right, Paul. I feel as if this whole Africa thing has changed my perspective on life. On what we’re all here for. I need to give it some more thought.’

‘Sure, Dave.’ He takes his cue and gets up to go, but I catch him glancing quickly around my office, sizing it up. Et tu, Brute? I’ll be on his case from now on. I’m glad we had this little chat. They say excessive drug-taking can make you paranoid, but I think that’s a good thing. Clearly Paul Ryan and I will have a different relationship in future.

TWO LIVERS is staying at the Cromwell Hospital, in a private suite which is filled with flowers and gifts and messages from well-wishers. Far more than I had. Why is that?

She’s still asleep when I arrive, and I take the opportunity to look around and check out the messages on some of the cards. Clients, colleagues, other firms and, of course, headhunters have all taken their cue and sent extravagant and unnecessary gifts and messages. I think they’re very extravagant and unnecessary.

On the bedside cabinet she has a pile of newspapers and cuttings of the coverage of our little escapade in Africa. ‘Hero Hart defies death, saves colleague’ and similar headlines stare gratifyingly at me.

I hear a stirring from the bed and go to sit beside her, dragging over a chair and crouching so that my face is close to hers. She’s wearing a simple cotton hospital gown through which I can see the outline of her perfect 34DDs moving as she breathes. I like this. If only she was feeling a little better there’d be some interesting role-play possibilities. Her eyes flutter open the way I’ve only ever seen happen in movies.

‘D–Dave …?’

I squeeze her hand. ‘I’m here.’

‘I–is it you, or am I dreaming?’ She looks confused, still half asleep. I want to say she’s dreaming: a really obscene, dirty dream in which she gets to perform all kinds of sex acts on her boss in a hospital bed. But she’s still recovering and from somewhere a voice of restraint holds me back. Time to be civilised.

‘Sure it’s me. I’ve been here ages, staring at you, worrying about you. Day after day. I was terrified we might lose you. I was terrified I might lose you.’ It’s bullshit of course. This is my first visit. I had Maria stay in touch with the doctors and they said that today she’d probably be awake for long enough for me to see her and have a sensible conversation. ‘So how are you?’

Or better yet, how’s your memory? Am I going to have to pay you off at bonus time so you don’t blow my cover on the whole hero thing?

She shakes her head. ‘Bad. Aching. Tired all the time.’

Phew, sounds good to me. I stroke her forearm gently, smiling a soft, reassuring smile. ‘That’s natural. Don’t you worry. Just try to forget all about it. You’re safe now.’

She frowns. Oh shit. ‘Dave …?’

‘Yes?’ Solicitous, patient, listening. Christ, I’m good. Really good. I should have been an actor. Maybe that’s why I’m so successful as an investment banker.

‘Dave … I’ve looked at the stories … the reports of … of what happened … out there.’

‘But you shouldn’t have. You mustn’t trouble yourself with all that. Draw a line.’

‘But … Dave …’

I’m sterner now, or at least mock stern, the way you can be when you have someone else’s best interests at heart. As if. ‘For once just listen to me, will you? Let yourself recover. This is a time for resting and healing.’ Oh yes, and forgetting. ‘And try to forget. Why stir up horrible memories?’

‘But there’s something you should know.’

Oh, fuck. ‘What’s that?’

‘I won’t ever forget …’ Her eyes fill with tears.

Christ. I can’t bear the suspense. I have to prompt her. ‘You won’t forget what?’

‘I … I … won’t ever forget … what you did for me.’ Yeehaa! Gotcha. Am I invincible or what?

I squeeze her hand again. ‘It was nothing. Honestly. Believe me. It was nothing at all.’

I’VE ALWAYS thought of myself as profoundly shallow. And selfish. Let’s not forget selfish. The kinds of things that bother ordinary people just don’t get to me. On the contrary, they simply pass me by. I regard it as a matter of professional pride to be a moral vacuum. Well, not exactly a vacuum, but morally neutral, the way markets are. So whether it’s cheating in exams or cheating on your wife, I take the view that rules are for little people.

In which case, why does the whole thing with Two Livers bother me so?

I should have been bothered this afternoon, when I was photographed handing over fat cheques to the grieving widows of my ex-pilots. They were still young, quite pretty, though too upset to be jumpable, with small children, all dressed in black, and we sat in a conference room while the bank’s lawyers explained the arrangements for the trust funds we’re setting up for the kids and the financial arrangements for the widows, and all the time a photographer snapped quietly away, getting me from all the best angles, showing how I was sharing the pain and the grief and making sure we could quietly – or not so quietly – tell the story to the media of how fair and generous I’ve been. With the bank’s money, of course.