9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

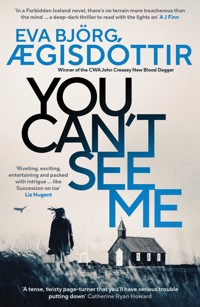

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Forbidden Iceland

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

A wealthy Icelandic family gathers for a reunion in a remote hotel on the isolated lava fields, but when someone goes missing, dark secrets are exposed and everyone is a suspect … the chilling, gripping prequel to the addictive, award-winning Forbidden Iceland series… `A country house mystery worthy of Agatha Christie´ The Times Crime Book of the Month `As storms rage, people fall prey to a sinister figure. A canny synthesis of modern Nordic Noir and Golden Age mystery´ Financial Times `In a Forbidden Iceland novel, there's no terrain more treacherous than the mind … a deep-dark thriller to read with the lights on´ A J Finn `Riveting, exciting, entertaining and packed with intrigue … like Succession on ice´ Liz Nugent **WINNER of the STORYTEL AWARD for Crime Book of the Year*** –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– The wealthy, powerful Snæberg clan has gathered for a family reunion at a futuristic hotel set amongst the dark lava flows of Iceland's remote Snæfellsnes peninsula. Petra Snæberg, a successful interior designer, is anxious about the event, and her troubled teenage daughter, Lea, whose social-media presence has attracted the wrong kind of followers. Ageing carpenter Tryggvi is an outsider, only tolerated because he's the boyfriend of Petra's aunt, but he's struggling to avoid alcohol because he knows what happens when he drinks … Humble hotel employee, Irma, is excited to meet this rich and famous family and observe them at close quarters … perhaps too close… As the weather deteriorates and the alcohol flows, one of the guests disappears, and it becomes clear that there is a prowler lurking in the dark. But is the real danger inside … within the family itself? Masterfully cranking up the suspense, Eva Björg Ægisdóttir draws us into an isolated, frozen setting, where nothing is as it seems and no one can be trusted, as the dark secrets and painful pasts of the Snæberg family are uncovered … and the shocking truth revealed. Succession meets And Then There Were None … A Golden Age mystery for the 21st Century, with a shocking twist. –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– `A tense, twisty page-turner that you'll have serious trouble putting down´ Catherine Ryan Howard `Your new Nordic Noir obsession´ Vogue `Confirms Eva Bjorg Aegisdottir as a leading light of Icelandic noir … a master of misdirection´ The Times Praise for the Forbidden Iceland series **Winner of the CWA John Creasey (New Blood) Dagger** **Shortlisted for the Petrona Award for Best Scandinavian Crime** **Shortlisted for the CWA Crime in Translation Dagger** **Shortlisted for the Capital Crime Award for Best Thriller** `Chilling and addictive, with a completely unexpected twist … I loved it´ Shari Lapena `Beautifully written … one of the rising stars of Nordic Noir´ Victoria Selman `Fans of Nordic Noir will love this´ Ann Cleeves `Eerie and chilling. I loved every word!´ Lesley Kara `Creepily compelling´ Heidi Amsinck `Elma is a memorably complex character´ Financial Times `Exciting and harrowing´ Ragnar Jónasson `Fantastic´ Sunday Times `So atmospheric´ Heat

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 491

Ähnliche

The wealthy, powerful Snæberg clan has gathered for a family reunion at a futuristic hotel set amongst the dark lava flows of Iceland’s remote Snæfellsnes peninsula.

Petra Snæberg, a successful interior designer, is anxious about the event, and about her troubled teenage daughter, Lea, whose social-media presence has attracted the wrong kind of followers. Ageing carpenter Tryggvi is an outsider, only tolerated because he’s the boyfriend of Petra’s aunt, but he’s struggling to avoid alcohol because he knows what happens when he drinks … Humble hotel employee, Irma, is excited to meet this rich and famous family and observe them at close quarters … perhaps too close…

As the weather deteriorates and the alcohol flows, one of the guests disappears, and it becomes clear that there is a prowler lurking in the dark. But is the real danger inside … within the family itself?

Masterfully cranking up the suspense, Eva Björg Ægisdóttir draws us into an isolated, frozen setting, where nothing is as it seems and no one can be trusted, as the dark secrets and painful pasts of the Snæberg family are uncovered … and the shocking truth revealed.

You Can’t See Me

Eva Björg Ægisdóttir

Translated by Victoria Cribb

Contents

Pronunciation Guide

Icelandic has a couple of letters that don’t exist in other European languages and which are not always easy to replicate. The letter ð is generally replaced with a d in English, but we have decided to use the Icelandic letter to remain closer to the original names. Its sound is closest to the voiced th in English, as found in then and bathe.

The Icelandic letter þ is reproduced as th, as in Thór, and is equivalent to an unvoiced th in English, as in thing or thump.

The letter r is generally rolled hard with the tongue against the roof of the mouth.

In pronouncing Icelandic personal and place names, the emphasis is always placed on the first syllable.

Names like Edda, Ester, Mist and Petra, which are pronounced more or less as they would be in English, are not included on the list.

Akrafjall – AAK-ra-fyatl

Akranes – AA-kra-ness

Ari – AA-rree

Arnaldur – AARD-nal-door

Arnarstapi – AARD-nar-STAA-pee

Axlar-Björn – AX-lar-BYURDN

Bergur – BAIR-koor

Birgir – BIRR-kir

Birta – BIRR-ta

Borgarnes – BORG-ar-ness

Breiðafjörður – BRAY-tha-FYUR-thoor

Búðir – BOO-thir

Djúpalón – DYOOP-a-lohn

Elín – EH-leen

Elísa – EH-leessa

Fróðárheiði – FROH-thowr-HAY-thee

Gestur – GHYESS-toor

Gísli – GHYEESS-lee

Hafnarfjall – HAB-nar-FYADL

Hákon – HOW-kon

Hákon Ingimar – HOW-kon INK-i-marr

Haraldur (Halli) – HAA-ral-door (HAL-lee)

Harpa – HAARR-pa

Hellissandur – HEDL-lis-SAN-door

Hellnar – HEDL-narr

Hörður – HUR-thoor

Hvalfjörður – KVAAL-fyur-thoor

Hyrnan – HIRD-nan

Ingólfur Hákonarson – INK-ohl-voor HOW-kon-ar-SSON

Ingvar – ING-varr

Irma – IRR-ma

Ísafjörður – EESS-a-FYUR-thoor

Jenný – YEN-nee

Knarrarklettir – KNARR-ar-KLETT-teer

Líf – LEEV

Maja – MYE-ya

Oddný – ODD-nee

Oddný Píla – ODD-nee PEE-la

Sævar – SYE-vaar

Sigrún Lea – SIK-roon LAY-ya

Smári – SMOW-ree

Snæberg – SNYE-bairg

Snæfellsjökull – SNYE-fells-YUR-kootl

Snæfellsnes – SNYE-fells-ness

Sölvi – SERL-vee

Stapafell – STAA-pa-FEDL

Stefanía (Steffý) – STEH-fan-ee-a (STEFF-fee)

Stykkishólmur – STIK-kis-HOHL-moor

Theódór (Teddi) – TAY-oh-DOHR (TED-dee)

Tryggvi – TRIK-vee

Valgerður – VAAL-gyair-thoor

Viðvík – VITH-veek

Viktor – VIKH-tor

The Snæberg Family

Evil creatures here abound

We must speak in voices low

All night long I’ve heard the sound

Of breath upon the window.

Sixteenth-century verse by

Þórður Magnússon á Strjúgi

Many thanks to my grandfather, Jóhann Ársælsson, for the poem on p.262.

This book is dedicated to my family.

Here’s hoping our next reunion won’t be quite as eventful as the one in this book.

Early Hours of the Morning

Sunday, 5 November 2017

She can no longer hear the music from the hotel.

The cold cuts through her flesh to the bone. However tightly she hugs her coat around herself, the wind always seems to find its way in.

Every nerve in her body is screaming at her to turn back. No good can come of running out in the middle of the night like this; she doesn’t know the surroundings well enough. She thinks about the family sitting over their drinks back at the hotel. Judging by the state they were in, no one will notice her absence straight away. If anything happens to her, it’s unlikely anyone will raise the alarm until the morning.

Lowering her head, she ploughs on, trying to move her fingers and toes, though she can hardly feel them anymore. She becomes aware of movement at the edge of her vision and darts a glance to the side. She sees the outline of a human figure looming through the falling snow, and her pulse starts beating wildly, until she realises that it’s only a lava formation in the vague shape of a man. She should be used to this by now.

She toils on, one step after another, trying not to panic. Time must be passing, but she has no idea how long she’s been walking. In the darkness and driving snow it’s as if time and space have ceased to exist.

Yet, strangely, it’s a relief to be outside. The hotel had started to feel like a trap, as if its concrete walls were closing in on her, making it hard to breathe. Now, all she can think about is getting in the car and driving home. Home to their house and her warm bed, and the mundane, everyday life that she’s only now realising is so precious to her. But she can’t go home yet. First, she has to keep walking, searching in the dark, terrified of what she might find. And even more of what she might not find.

When she turns her head, she can make out the face under its hood, cheeks red with cold. The expression’s not unfriendly, but there’s something sinister behind the eyes that she’s never seen before. Or perhaps she just didn’t want to see it.

She starts walking faster, but the feeling of being trapped hits her even more strongly than before. And the thought crosses her mind that maybe it wasn’t the hotel that had given rise to the feeling of claustrophobia, but the people staying there. Her family. The person walking only a few steps behind her in the dark.

Two Days Earlier

Friday, 3 November 2017

Irma

Hotel Employee

My eyes flick open the instant I’m awake, like a light bulb being switched on. There’s a faint aroma of coffee wafting down from the kitchen above my room, and I inhale deeply, then roll over onto my back and stretch.

Today is Friday. I start work at midday, taking the noon-to-midnight shift, as I do every Friday. As it’s still only eight, I could have a bit of a lie-in if I wanted and go back to sleep or read the book on my bedside table, but I’m too excited.

The feeling reminds me of gearing up for a night out when I was younger. That flutter in your stomach at the prospect of having fun.

They’re coming today, sings the refrain in my head, and I smile like a small child at Christmas.

I know it’s silly to feel so excited. It shouldn’t be a big deal; and it isn’t – or wouldn’t be for most people – but there’s going to be a family reunion at the hotel this weekend. Or maybe I should call it a birthday celebration. The woman who rang to make the booking explained that her husband’s grandfather would have been a hundred on Sunday, so his descendants are spending the weekend together in his honour. They’ve booked out the entire hotel, even though they won’t be able to fill all the rooms.

It might not sound like a good reason to get in a tizz, but this is no ordinary family. The Snæbergs are only one of the richest and most powerful clans in Iceland. Ingólfur, who would have been a hundred on Sunday, was the founder of Snæberg Ltd, which is pretty much a household name these days – a huge business empire by Icelandic standards, with hundreds of employees and an annual turnover in the billions of krónur.

Not that I know much about the business side of the company or its history. All I know is that the family is super rich.

Rising to my knees, I draw back the curtains. It’s almost completely dark outside, as there’s still a good hour until sunrise, but it’s just possible to glimpse the jumbled, moss-covered rocks of the lava field stretching away on every side. Since starting work here, I’ve often caught myself wondering if I’ll ever be able to move back to the city; to my flat with its view of my neighbour’s windows and the dustbins in the alley below.

I fetch my laptop from the desk and climb back into bed, then tap ‘Snæberg’ into the search engine and study the images that come up. They include a number of well-known faces, people who have made their mark in Icelandic business and political circles, as well as younger family members who are prominent on the party scene. Some of them can barely leave the house or post anything online without the media turning it into a news item.

Hákon Ingimar is one of the younger generation. He was in a relationship with an Icelandic singer until fairly recently, and after that he hooked up with a Brazilian supermodel.

I click on a recent news item about Hákon Ingimar and see that he and the model have broken up, though the report about their split is accompanied by a photo of them in a clinch. With his blond, blue-eyed good looks and the golden tan revealed by the rolled-up sleeves of his shirt, you’d say he should be starring in a film or an aftershave advert. His now ex-girlfriend would cast most girls in the shade, with her luscious lips and those endless legs.

They’re both so stunning that it’s almost impossible not to feel envious. Not to wonder what it would be like to be them; to be rich and beautiful and free to do almost anything you like. Go on a spontaneous weekend break to Paris, shop for clothes and buy exactly what you want. Whereas I can barely even afford to do a food shop at the supermarket without getting a sinking feeling in my stomach when I present my card.

I bet Hákon Ingimar has never been in that position. You only have to look at social media to realise that he has no cash-flow problems. In his photos he’s always dressed in designer clothes (although half the time he’s undressed), quaffing expensive wine at five-star hotels, surrounded by friends and admirers. I bet Hákon Ingimar has never been lonely; he’s too popular for that.

I’ve never been popular. I’ve always struggled to make friends and hold on to them. Had to be the one who knocked on the door or picked up the phone. I’ve been told I’m too clingy and don’t know when to back off. The truth is, you’re only seen as too clingy if people don’t want you around. Yet another problem I bet Hákon Ingimar doesn’t have.

I take a deep breath and remind myself that comparisons like this aren’t helpful. And it’s not like the Snæberg family were handed everything on a plate, not to begin with, anyway. Ingólfur, Hákon Ingimar’s great-grandfather, started his first business at seventeen years old, using the small fishing boat he operated out of a village, here in the west of Iceland. He worked hard all his life for his wealth. His descendants have capitalised on his success, and although that’s easier than starting from scratch like him, they must have done something right to have preserved the family fortune.

Scrolling back, I spot Petra, another of Ingólfur’s great-grandchildren. As far as I know, Petra Snæberg doesn’t work for the family business, though of course she’s benefited from its success. Instead, she has her own interior-design and consultancy company. She’s got thousands of followers on social media and collaborates with various firms. You can’t open a newspaper or online media platform without seeing her face in adverts with the slogan: ‘Why not invite Petra round and convert your home into a sanctuary?’

‘Sanctuary’ is a word she’s forever trotting out, like, she’ll say: ‘Your home is above all a sanctuary, a place that reflects the inner you.’

If people started judging my inner me by the state of my flat in Reykjavík, I’d hate to hear the verdict. It’s not like I’ve put any particular thought into how things are arranged. They’re just there because that’s where they ended up. The shelves are just shelves; a place to keep things. My flat is just a flat, and I certainly don’t regard it in any sense as a sanctuary.

Opening Petra’s Facebook page, I scroll through her photos.

She’s got a husband called Gestur, and from the pictures it’s not immediately obvious how he and Petra got together. All I can say is that he must be a real charmer in person. Gestur works as a programmer at a drugs company, but no doubt he’ll end up at the family firm one day, like most people who marry into the Snæberg clan. In fact, I’m surprised he hasn’t already made the move.

Gestur and Petra have two children, Ari and Sigrún Lea, always known as Lea. Cute little names, more suitable for small children than adults. And they certainly are cute in the photos from when they were kids: Ari in his sports kit, his hair almost white in the summer sun; Lea, a robust little girl, beaming to reveal oversized front teeth, her dark hair so long it reaches below her waist.

Lea is older than Ari, but not by much – two or three years, maybe. I click on her name, but the page that comes up contains next to no information. She’s much more active on Instagram. On her profile there you can see that the little girl with the big front teeth now wears a pout and a crop top. No longer robust but slender, her long hair tied back in a pony-tail apart from two locks left free to frame her face. She reminds me of a singer – I’ve forgotten her name – who’s also petite and slim, with long, dark hair and chocolate-brown eyes.

I examine the background in Lea’s pictures, trying to peer into her room, her life, but I can’t see anything of interest. Nothing that provides any more insight into who she is or what she does. A lot of the photos on her page have been taken abroad, in big cities or holiday resorts. In one, Lea’s on a beach wearing a bikini; in another, she’s in Times Square, toting a Sephora shopping bag, and in yet another, at the London Eye with a Gucci one. Only sixteen but already far more cosmopolitan than me. I wonder how often she goes abroad each year; what kind of hotels she and her family stay in.

Pushing away my laptop, I tell myself aloud to stop it. Envying people is not my style. But no matter how often I remind myself that the Snæbergs must have their problems, like the rest of us, I can’t help wondering what it would be like to be them.

Later today they’ll all be here at the hotel, and I’ll get to see with my own eyes whether they’re as perfect as outward appearances suggest. Perhaps what excites me most is the thought of looking more closely and spotting all the little cracks that must lurk under that perfect veneer. Because of course they’re not perfect.

Nothing is perfect.

Now

Sunday, 5 November 2017

Sævar

Detective, West Iceland CID

There was a deep gash in the mountainside, as if someone had taken a giant cleaver and split it in two. Sævar raised his eyes to the top of the precipice, many metres above, and felt weak at the knees. A fall from that height would be impossible to survive, as the evidence at their feet made only too clear.

‘That was a heck of a drop,’ Hörður said, stating the obvious.

‘Yes.’ Sævar’s voice emerged in a croak, and he coughed. Hastily lowering his gaze, he concentrated on his shoes and blinked. He’d suffered from vertigo ever since, as a small boy, he’d witnessed one of his friends falling from the first floor of a block of flats. They’d been climbing on the balcony rail, daring one another to dangle over the edge. When his friend lost his grip and plummeted backwards into the redcurrant bushes below, Sævar had been convinced that he was dead. But, by a stroke of luck, he’d got off with no more than a broken arm and a few scratches, which he boasted about for weeks.

For a long time afterwards, Sævar had suffered from nightmares in which he felt the air rushing past him as he made a headlong descent, as if it was he who had fallen and not his friend. He would wake up frantically clutching the duvet, sometimes on the floor, but usually still in bed, drenched in sweat, his heart pounding. Even now, all these years later, he couldn’t stand heights and could hardly even think about them without growing dizzy.

To distract himself, he concentrated on the body lying at their feet. From a distance, it had blended into the surrounding landscape, the grey down jacket resembling a rock jutting out of the snow, but as they drew closer it had resolved itself into a human figure, its limbs sprawling in an unnatural position, dusted with a thin layer of snow.

Sævar watched as Hörður bent down, head on one side, then raised his camera. The clicking as he snapped away seemed incongruous in the profound silence.

Sævar was familiar enough with Hörður’s slow, careful working methods to realise that they would be here for a while. They had been colleagues at Akranes Police Station for several years, but Sævar had only been working directly for Hörður for two, when he was promoted to detective. Now they worked closely together every day, as part of a three-man CID team covering the west of Iceland.

Sævar raised his eyes again to survey their surroundings. Beyond the snow-capped peaks of the mountains near at hand, he glimpsed the white flanks of the Snæfellsjökull glacier, rising like a great dome at the end of the peninsula. A few birds floated so high overhead that it was impossible to identify them, though he could hear the distant screeching of gulls from the shore. The nearby road seemed to be little used, apart from the odd car that drove past and almost immediately vanished out of sight down the slope.

There had been a blizzard during the night, but the gale-force wind had scoured the ground clean, leaving only scattered snowdrifts. Now the weather was breathlessly still, beautiful in its tranquillity. The calm after the storm, Sævar thought. Or should that be before? He couldn’t remember.

Before he had a chance to study the landscape in any more detail, Hörður called out:

‘See that?’

Sævar moved closer. Again, he was hit by a wave of dizziness and had to swallow a mouthful of saliva. The precipice looming over him felt menacing, though common sense told him there was nothing to fear.

‘What is it? Can I see what?’

‘There.’ Hörður pointed to the victim’s hand.

It took Sævar a moment to work out what Hörður was referring to, but then he saw it. Saw the dark strands of hair protruding from the clenched fist.

Two Days Earlier

Friday, 3 November 2017

Petra Snæberg

I’ve been running round the house like a headless chicken all morning, cursing the size of the place – not for the first time. Three hundred and sixty-five square metres, thank you very much: two storeys, a basement and a double garage. Although it seemed like a good idea at the time to put the kids’ bedrooms on a different floor from ours, in practice it makes trying to keep the house tidy between the cleaner’s visits a total nightmare – not to mention finding anything that’s lost. Just now, for example, all the chargers seem to have vanished into thin air, which is unbelievable given how many there are in the house. I suspect they’re all lying on the floor in either Ari or Lea’s bedroom, but they swear they haven’t got them and of course I’m not allowed in there to look for myself. I bet they haven’t even bothered to check.

‘Lea! Ari!’ I call downstairs to the basement, not for the first time this morning. ‘We’re leaving in ten minutes. Bring up your bags. Dad’s packing the car.’

I wait for an answer, but of course it doesn’t come.

Well, that’s their problem. I run a hand through my hair, glancing distractedly around me. Breakfast still hasn’t been cleared away. There are bowls of milk and soggy Cheerios on the kitchen table. No way am I leaving them there all weekend.

While I tidy up, I review my mental list of everything that still needs to be done and everything I’m bound to have forgotten. The house is a tip. After Gestur got home late last night, everything went a bit pear-shaped, and I stormed off to bed without doing any of the chores I had meant to deal with before going to sleep.

It’s not like me to leave my packing until the evening before. Usually I’m on top of everything: birthdays, dinner parties, special occasions. I’m the type who makes to-do lists. Few things give me more pleasure than putting a little cross by the tasks I’ve accomplished. On my computer I have individual pre-prepared checklists specially tailored for beach holidays, city breaks and trips to the Icelandic countryside. Being disorganised is not an option. If it weren’t for my organisational skills, I would never have been able to keep the family together while simultaneously setting up my business.

Most people think I got everything handed to me on a plate thanks to my family connections, but nothing could be further from the truth. I built up my firm, InLook, which specialises in interior design and consulting, through my own hard work, and it took several years before it turned any real profit.

Because Gestur studied business and computing, he was able to help me with the practical side of things, like budgeting and project schedules. At first, I took care of all the rest myself: project acquisition, hands-on interior design and social media. But since then I’ve hired people to take on some of these jobs, and now my role is mainly restricted to conducting the initial meetings with clients, the meetings at which ideas are thrown around and I get a better idea of their requirements. This is harder than it sounds, because people often have no idea what they actually want.

In the beginning, my clients tended to be private individuals, but in recent years I’ve branched out, designing everything from homes to workplaces. Today, I’ve got a team of fifteen people working for me, eight of them designers, including me, and I’ll soon need to hire more. I can hardly keep up with demand, and in the last year I’ve paid my parents back every last króna of their original investment in my business.

So it hurts when people say I’ve been handed things on a plate, because it undervalues all the sheer hard graft I’ve put in over the last ten years. Sure, my parents provided the initial capital and helped set the company up, but I’m the one who did all the rest. I developed the brand, took care of the marketing, built up a client base and hired the staff. Recently everything’s been going so well. Brilliantly, in fact. I should be so bloody happy.

I close the dishwasher and switch it on, though it’s nowhere near full. Then I lean against the kitchen counter, listening to the regular sloshing of the machine.

Yesterday’s empty wine bottle is still on the table. Becoming aware of the sweetish-sour smell, I chuck it in the bin and shove it down out of sight. I drank most of it alone in front of the TV last night while Gestur was out. I needed something to calm my nerves. For the last few weeks I’ve had this voice in my head, counting down the days until the family reunion: three, two, one…

I smile at Ari, who has finally come upstairs, but my smile fades a little when he fetches a bowl and takes out the packet of cereal I’ve just put away.

‘What are you doing?’ I ask.

‘Having breakfast,’ Ari replies, with that what’s it to you? tone that comes so naturally to teenagers.

‘I’ve just cleared things away, Ari,’ I protest plaintively. ‘We’re about to leave.’

Ari mumbles something and pours milk into his bowl.

I stand there, watching him in silence. Studying the beautiful blond hair that’s far too long but looks so good on him. When he was small, he had white curls, but now it’s just attractively wavy. He has the kind of smooth, flawless skin that any beautician would die for, but his sharp, angular jawbone prevents his face from appearing too delicate.

Ari has always been my weak spot, the child I can’t say no to and always end up giving everything he wants. The child who makes me smile – just the thought of him is enough. I can’t be angry with Ari.

‘What happened to your fingers?’ he asks.

‘Nothing,’ I say, clenching my fists to hide my nails. The cuticles and surrounding skin have never looked worse. The fact is, I’m a biter, and would probably gnaw my fingers right off if I didn’t restrain myself. But I haven’t chewed my nails this badly for years, not since I was a teenager, so I must have done it in my sleep. When I woke up, the pillowcase was spattered with tiny spots of blood and there was an iron taste in my mouth. Two of my fingers are now wrapped in cartoon-animal plasters – the only ones I could find – as if I were a small child.

Ari furrows his brows, which are much darker than his hair. As a child, he was nothing but eyes. His long, dark lashes resembled those of a doll.

Gestur enters the kitchen, accompanied by a cold gust of air. He’s left the front door open, and out of the corner of my eye I can see the bushes in front of the house. The wind is whirling the shrivelled leaves around on the pavement. The sound they make as they rustle over the paving stones seems suddenly loud, as if someone has turned up their volume and muted everything else. Three, two, one…

‘I’ve filled the tank,’ Gestur says.

‘Great.’ I beam at him and fold my arms across my chest. ‘Then we can go.’

Tryggvi

Until three days ago, talk of the weather dominated the Facebook page the family set up to organise the trip. According to the original forecasts, it was supposed to be unusually fine for an Icelandic November: sunny, windless, relatively mild and mostly dry. People posted jokey comments, asking if everyone had invested in sunscreen. Then, on Tuesday, the forecast did a U-turn, and now they’re predicting snow and gales; the first depression of the winter is due to make landfall on Saturday, causing temperatures to plummet, or so the weatherman claimed yesterday as he warned people against travelling. I itch to bring up the sunscreen joke again but doubt anyone would appreciate it. Luckily, the bad weather isn’t expected to arrive until late in the day, so we should still be able to fit in the cruise of Breiðafjörður, which is scheduled for noon on Saturday.

I find it funny that no one in the family has even mentioned the latest forecast. For the last few days, Oddný has stopped watching the TV the second the weather report comes on. I’m guessing she’s refusing to accept the forecast. She’s just decided to ignore it.

Perhaps she thinks bad predictions don’t apply to the Snæberg clan. Sometimes I think Oddný’s family really believe they’re not governed by the same rules as the rest of us.

I glance at Oddný, sitting in the passenger seat beside me. She’s tarted herself up a bit for the occasion, put on make-up and blow-dried her hair, but she’s dressed casually, in a beige, zip-up fleece and black trousers. Smart but not too smart. Oddný has always known exactly how to tread the middle line.

She’s in a good mood and turns up the radio as Bon Jovi sings about living on a prayer. Out of the corner of my eye, I can see her fingers tapping in time.

‘We should stop at Vegamót,’ she says. ‘Get something to eat.’

‘We can do that.’

‘I didn’t have any breakfast. And I wouldn’t mind trying their seafood soup again.’

We’ve been up the west coast to the Snæfellsnes peninsula once before, though that was to stay in Oddný’s family’s summer cabin. The place turned out to be rundown and badly in need of maintenance, so while we were there, eager to do my bit, I oiled the deck and did a spot of DIY. Not that anyone seems to have noticed; at least, no one’s said a word.

‘It’s a fair while since we last saw Haraldur and Ester,’ I say. ‘When was it again? At the confirmation party last spring?’

‘Yes, I suppose it was,’ Oddný says. ‘Don’t be shocked if Ester’s changed.’

‘How do you mean? Changed in what way?’

Oddný sounds gleeful. ‘She’s had a facelift. Had all the skin stretched back to smooth out her wrinkles. Ester’s always been rather vain. According to Ingvar, she looks as if she’s been facing into the wind too long.’

‘Has she really had a facelift? You’re not pulling my leg?’

‘No, I’m not.’ Oddný pulls down the sun visor, peers into the small mirror on the back and runs a finger over one of her eyebrows. ‘But I bet she won’t admit it. Like the time she had her eyelids done and tried to act like nothing had happened. I’m sure Halli made her do it.’

‘Halli?’ I say. ‘You reckon?’ Oddný’s brother Haraldur is the controlling type all right, but ordering his wife to have plastic surgery is going a bit far, even for him.

‘You know what he’s like,’ Oddný says, pushing the visor up again. Smiling at me, she adds: ‘I’m so lucky compared to my sister-in-law.’

‘I wouldn’t want to change a single thing about the way you look,’ I say, and I mean every word.

Really, I’m the lucky one. Oddný’s far too good for me. Her family agree. They can’t understand what she sees in a weather-beaten, penniless carpenter like me, but then I can hardly understand it myself.

I haven’t belonged to this family for long, in fact I find it ridiculous to talk about belonging to it. Me and Oddný, we’re polar opposites, to be honest. We hardly have anything in common.

When we reach the red-roofed café at Vegamót on the southern side of the Snæfellsnes peninsula, we go inside and order soup and a sandwich, then take one of the tables by the window. The mountainous spine of the peninsula and the glacier at its tip are hidden from view behind the café: all we can see is flat pastureland, then the great sweep of Faxaflói bay. We sit silently watching the passing traffic. I’m halfway through the sandwich when I hear Oddný’s name being called in a questioning voice.

Oddný’s face lights up when she sees her older brother, Ingvar, and his wife, Elín. Putting down her glass of water, she gets quickly to her feet.

‘You here?’ Oddný’s voice is so loud and piercing that everyone in the café must be able to hear her.

I stand up as well to greet them. There are hugs, kisses and demands for news.

‘Shouldn’t we toast the occasion?’ Elín says, and she and Oddný charge over to the counter.

Ingvar asks about the holiday Oddný and I took in Spain last month. ‘Must have been nice to get away to the heat.’

‘Yes, very,’ I say, because it’s the answer people want to hear. But the truth is, I think hot weather is overrated: I get no pleasure from lying beside a pool, knocked out by the heat, with nothing to do. I feel like I can’t breathe properly until I’m back in the cold, fresh north wind of home.

The women return with two mini bottles of white wine and two beers.

‘It’s like that, is it?’ Ingvar says, and the sisters-in-law giggle like schoolgirls.

No one mentions the fact we’ve still got another forty kilometres or so to drive. I don’t touch my drink, but then Oddný knew I wouldn’t, and once she’s finished her wine, when nobody’s looking, I nudge my glass towards her.

‘Isn’t Hákon Ingimar coming?’ Ingvar asks.

‘Yes, but he’ll be a bit late,’ Oddný says, as usual smiling indulgently when her son is mentioned. ‘Hákon’s always so busy.’

‘So I gather,’ Ingvar says, no doubt referring to all the stories in the news about Hákon Ingimar forever turning up at parties with a new girl on his arm.

‘He’s appearing in an advertisement,’ Oddný says, rather proudly. ‘On a glacier.’

‘Which glacier?’

‘He didn’t say,’ Oddný replies. ‘It’s an advert for outdoor clothing.’

‘Oh,’ Ingvar says. ‘I thought you were supposed to advertise swimwear on glaciers.’

We all laugh. I dimly recall seeing a photo of Hákon posing in swimming trunks against a wintry landscape. Then the conversation turns to the upcoming weekend – who’ll be there and who won’t, and what everyone’s children are up to these days.

Oddný has two older brothers, Ingvar and Haraldur, who are both married, with grown-up kids. It took me quite a while to work out which children belonged to who and what their names were, but I’ve more or less got it straight now – I hope. And I shouldn’t forget Oddný’s father, Hákon, who’ll be arriving on Saturday evening for the party. He’s eighty and was diagnosed several years ago with a degenerative disease and has gone downhill a lot recently.

Oddný has two children from before we got together: Hákon Ingimar and Stefanía, known as Steffý. Hákon Ingimar, or Hákon junior as some people call him, is a bit of a special case, to be honest. Oddný always makes out like he’s got all sorts going on, but as far as I can tell all he really does is stare into a camera lens day in, day out, though mostly the camera of his own phone, which he’s never parted from. Still, it’s not my place to judge. After all, I grew up in a different time. I suppose you could say I’m the product of a totally different world.

I’ve only met Stefanía a couple of times as she lives in Denmark, where she works for some sort of cosmetics company. She has a posh engineering qualification, only I can’t remember what kind.

I didn’t have children myself until I was thirty, when I met a woman with a five-year-old boy. I raised him as my own kid, and he’s been a part of me ever since, though Nanna and I split up donkey’s years ago. The boy didn’t have a father, at least none worthy of the name, and I saw it as an honour to be allowed to play that role in his life. I was totally unprepared for how tough and at the same time rewarding it was to be responsible for a child – for all life’s events, big and small. I took him along for his first day at school, taught him to read, escorted him to swimming lessons and watched, tearful with pride, as he graduated from school. Getting to be his dad is the best thing that’s ever happened to me – nothing else has ever come close.

‘Well, best hit the road,’ Oddný says, finishing my glass.

As she stands up, her bag falls on the floor, and she and Elín burst out laughing. Oddný’s cheeks are flushed, as always when she drinks. I feel a twinge of anxiety, but push it down. I’m sure it won’t be as bad this time.

During the year and a bit that we’ve been together, it’s been impossible not to notice that Oddný’s family is unusual, to say the least. Of course, I was aware of who the Snæbergs were, but I hadn’t taken any interest in their affairs, since I rarely read the gossip columns or business pages. Maybe I’d have been better prepared if I had.

The family has its fair share of big egos, and they can be touchy as hell. I’ve seen how a single innocent comment can trigger a violent quarrel, where one person blurts out something that would have been better left unsaid and another person storms out. To understand what they’re like, it’s probably best to imagine a herd of hippos wallowing in too small a waterhole, all of them constantly bumping up against the others. When personalities that strong get together, you never know what will happen, but you can bet your life that sooner or later there will be a showdown of some kind.

Petra Snæberg

‘Say cheese!’ I hold up my phone and take a picture of us all in the car. The kids smile half-heartedly in the back seat, and I’m hit by a sudden memory of how sweet they used to be when they were small, beaming and yelling ‘cheese!’. Now they’re both sitting with their wireless ear buds in, their faces blank. A lot has changed since the days when long car journeys had to be carefully organised, with hourly breaks and CDs of children’s songs or stories playing at full volume, while you crossed your fingers and prayed that the peace would last. Now the silence is absolute, and I almost miss the squabbles. I miss the time when my children’s problems mainly revolved around deciding who got to choose the next song.

‘Is everything OK?’ Gestur asks in an undertone, so the kids won’t hear.

‘Yes, of course,’ I say, my voice artificially cheerful.

Gestur knows me well enough to see through the pretence. ‘You had a nightmare last night. I thought you’d stopped getting them.’

‘Oh, did I?’

Gestur doesn’t answer. He knows I’m lying. I remember perfectly well what I dreamt about last night. It’s a recurring nightmare I’ve been having ever since I was a teenager. In it, I’m standing alone in the middle of the road at the foot of Mount Akrafjall. It’s pitch-dark, and after a while it starts to snow. All is quiet and peaceful. Then suddenly there’s a blinding white light and I wake up, jolted out of my dream with the gut-wrenching certainty that something terrible has happened.

Mum sent me to see a therapist after the nightmares had been playing havoc with my sleep for several months. My parents always believed a professional should be brought in to solve most problems. When I was having difficulty with maths as a ten-year-old, they hired a tutor, and again, later, when I started making clumsy mistakes on the violin as a secondary-school pupil, a psychologist was drafted in. My parents always assumed they should farm out our problems to experts, rather than simply sitting down and talking to us themselves. I know they meant well, but sometimes I wonder why they didn’t just ask us first what was wrong.

Having said that, I’d never have admitted to them that I knew exactly why I was suffering from nightmares.

‘And there’s that nail business too,’ Gestur adds, still in the same level tone.

‘Nail business’ is what Gestur calls it when I chew my cuticles.

‘It’s nothing,’ I say, instinctively shoving my hands out of sight between my thighs.

Silence envelopes us again. Unlike me, Gestur doesn’t have a problem with silences. They don’t seem to bother him.

I turn my attention to the passing scenery. It’s a beautiful day, and there’s an old hit playing on the radio that reminds me uncomfortably of my youth. The feeling is heightened as we pass the turn-off to the little west-coast town of Akranes.

I really want everything to go well this weekend. It’s been a long time since the entire family last gathered for a reunion. We used to be so close when I was younger and still lived in Akranes. My grandparents lived next door, and so did Dad’s brother and sister, and I used to wander freely in and out of their houses. In fact, my cousins, Viktor and Stefanía, were my best friends. Steffý and I were born the same year and grew up almost like sisters; we were inseparable in those days. ‘Joined at the hip,’ Dad used to say.

I often think about Steffý. The image of her face comes into my mind when I least expect it: at night before I drift off to sleep; when I’m watching my daughter with her friends, or hear the loud, shrill laughter of children. The emotions it evokes are a mixture of loss, sadness and regret for what might have been.

Strange how our formative years remain such a large part of us, despite being only a small part of our lives as a whole.

We drive on up the coast, past the steep, dark slopes of Mount Hafnarfjall, where the lowland is clothed with birch scrub, the branches winter bare, apart from a few clusters of dead brown leaves. The only buildings are lone farmhouses here and there, flanked by dilapidated barns and cowsheds, until eventually the little town of Borgarnes gleams white on the other side of the fjord.

‘Mum,’ Ari says, and I turn down the music. ‘Can we stop at Hyrnan? I’m thirsty.’

‘Me too.’ Lea pulls out one of her ear buds. ‘And I need the loo.’

‘OK, we’re stopping at Hyrnan,’ Gestur says, and I catch him and Lea exchanging grins in the rear-view mirror.

Lea has a very different relationship with her father to the one she has with me. They go out on runs together and occasionally go swimming in the mornings before work and school. Sometimes I come home to find Lea watching TV with Gestur, but when I’m there she tends to shut herself in her room. Whenever I try to talk to her, she suspects me of having some ulterior motive, as if I’m trying to get her to do something or looking for an excuse to tell her off.

We pull into the car park by Hyrnan, and the kids run inside to the counter. I let Gestur take care of their requirements while I buy some fizzy water and a toothbrush for myself.

When I have paid for these, I find a painkiller in my bag and quickly swallow it. Gestur thinks I use any excuse to take painkillers, so I’ve started knocking them back furtively, as if I have something to hide. But the truth is that my head is throbbing from that bottle of wine last night.

I’m rooting around in my bag again, this time in search of my sunglasses, when I hear a voice saying my name.

‘Petra?’ Next minute Viktor is standing in front of me, holding out his arms: ‘Fancy meeting you here.’

I smile and step forwards into Viktor’s embrace. He was always very touchy-feely as a teenager, and clearly nothing’s changed. His hug is tight and intimate, his face so close that I can see every pore and line, not that he has many lines. In fact, he’s only got better-looking with age, his features becoming more defined, his smile gentler.

‘How are you?’ Viktor is studying me, still with his arms round my shoulders. ‘It’s been such a long time.’

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘Months.’

Viktor and I used to meet up regularly. He’d come round in the evenings, mainly when Gestur was at choir practice, bearing wine and treats like chocolate or mini desserts. But over the years I found it more and more of an effort to keep up our relationship, until in the end it began to feel like a chore. I started inventing excuses to put off seeing him, and in the last few years the intervals between our meetings have grown ever longer.

Eventually, Viktor must have realised that the impulse to keep up our connection was one-sided. It was always him ringing me and me pretending to be busy.

‘Is it that long? That’s shocking, Petra. Shocking. We’ll have to do better in future.’ Viktor shakes his head. ‘So, what are you up to these days?’

‘Oh, same as usual. Running the company and the family. Apart from that, things are pretty quiet.’

‘Quiet? That doesn’t sound like you,’ Viktor says, reminding me how well he knows me. That he knows I can never sit still, that I have to be permanently on the go.

I’m about to add that he’s no different himself, when a young woman appears beside him and hands him a hot dog.

‘They didn’t have any of the hot mustard,’ she says.

‘Damn,’ Viktor replies, then adds: ‘This is Maja, my girlfriend. Maja, this is Petra – who I’ve told you about.’

‘Yes, of course. Nice to meet you, Petra.’ Maja holds out a thin arm, smiling. I’m struck by how young she is, at least ten years younger than Viktor, closer in age to Lea than to me. She looks foreign, with black hair and olive skin.

‘Likewise,’ I say, shaking Maja’s hand. Then I look back at Viktor: ‘I wasn’t sure you’d be coming.’

‘I wouldn’t miss this for the world,’ he says, and I can’t tell from his tone whether he’s being sarcastic. ‘But seriously, I’ve been looking forward to seeing you.’

‘Do you know if Steffý’s coming?’ I ask. When I asked Mum, it was still a bit up in the air whether Stefanía would make it. I don’t think even her mother, Aunt Oddný, knew for sure.

‘Yes, she is,’ Viktor replies. ‘I heard from her yesterday.’

‘What fun,’ I say, and wince at how false it sounds.

‘It’ll be just like old times.’ Viktor laughs.

‘Exactly,’ I say, gnawing at my cuticles again.

Viktor chucks his hot-dog wrapper in the bin, and they say goodbye. I stand there watching them leave. Viktor puts an arm round Maja’s shoulders, and she looks up at him, smiling.

Viktor’s changed; he seems so much more relaxed and self-assured than he was in his teens. Now he gives off a laid-back aura that leaves me feeling like an uptight middle-aged woman and makes me oddly nervous around him. It’s almost like he’s a stranger, although we know each other so well.

I suppose it’s always a bit disorientating when you have only casual contact with someone you used to be very close to. Dad’s brother, Ingvar, and his wife, Elín, adopted Viktor in 1984 and we pretty much grew up together. Viktor was with me the day I started my periods and the first time I got drunk. When I cried myself to sleep, Viktor held me all night in his arms. Since then, time has created a certain distance between us, despite our sporadic meetings over the years. But the fact that Viktor knows exactly when and with whom I lost my virginity makes all small talk between us feel distinctly weird.

‘Who was that?’ Gestur asks, finally coming over, loaded down with sweets and drinks.

‘Viktor.’

‘Oh, he’s coming, is he?’

I nod.

‘Was he alone?’

‘No, actually,’ I say. ‘He was with his girlfriend.’

‘I didn’t know he had a girlfriend.’

‘Neither did I.’

‘Good for him,’ Gestur says, though he doesn’t sound as if he means it.

He and Viktor have never got on. We tried inviting Viktor over for meals a few times, but the conversation was strained at best. Viktor finds Gestur far too stiff and formal, while Gestur thinks Viktor hasn’t moved on since he was twenty.

Sometimes I get the impression Gestur is jealous of Viktor, because Viktor and I are cousins and have known each other forever. It’s perfectly natural that we should find it easy to talk to each other and that we know (or used to know) almost everything about each other, as I’m sure Gestur is aware. But perhaps it’s just in a man’s nature not to want his wife to be close to another man, even if he’s a member of her family.

‘You’re so unlike yourself around him,’ Gestur once said, soon after we got together. I can’t remember how I answered, but I do recall thinking that it was the other way round: I could be myself with Viktor; it was with Gestur that I felt I had to be somebody else.

‘Oh, Petra,’ Gestur says suddenly, grimacing at me.

‘What?’ I say, guiltily jerking my hand from my mouth. When I lick my lips, I taste blood.

*

Once we’re back in the car, I find some flesh-coloured plasters in the glove compartment to replace the cartoon ones. It occurs to me that I’m no better than Lea, who went through a phase of gnawing her nails to the quick; or Mum, who, when I was younger, used to spend her evenings pulling out her eyelashes. I still shudder when I remember the crumbs of mascara on her cheeks and the eyelashes littering the coffee table.

Sometime later, we drive past the narrow, white ribbon of the Bjarnarfoss falls, cascading down the sheer rockface of the mountainside, and I attempt to lighten the atmosphere in the car. Twisting round to the back seat, I say:

‘Did you know that some people can see a woman in the waterfall?’

‘What?’ Ari pulls out his ear buds, but Lea’s tapping away on her phone and doesn’t even look up. Her cheeks are delicately flushed, her lips parted in a smile. I think she must have a boyfriend, or that she’s talking to a boy, but she just snorts and rolls her eyes when I ask.

‘Some people say there’s a woman who sits in the middle of the waterfall, combing her hair,’ I continue.

Ari glances out of the window. ‘Cool,’ he says, then puts his ear buds back in.

I smile at him and surreptitiously study Lea. The daylight illuminates her dark-brown hair, which she’s drawn up into a pony-tail on top of her head.

Lea’s been unusually quiet lately. I’m sure something’s bothering her, but I have no idea what it is. I remember what it was like to be sixteen, though I know Lea would never believe it. She can’t believe anyone in the world has ever been through what she’s experiencing. Least of all me. In some ways she’s right: the world teenagers face today is very different from how it was twenty or thirty years ago. But I still have a vivid memory of what it is like when your self-esteem depends on other people’s opinions. The difficulty of finding a balance between fitting in and standing out. Between being ordinary and at the same time special.

Being a teenager doesn’t seem to have affected Ari the same way: he’s always himself. In contrast to Lea, he seems to find everything so easy. Yesterday morning, for example, he asked me what the hotel was like, and I showed him some pictures.

It’s brand new, built in the middle of an old lava field on the south side of the Snæfellsnes peninsula, not far from the village of Arnarstapi and the glacier. Previously there was a farm on the estate, which belonged to the local government official and his family. According to the hotel website, the farm was abandoned after a fire in 1921, but you can still see the ruins. The story goes that the official’s wife died in the fire along with their two youngest children. I closed the information window before Ari could read that far.

Apparently, the hotel is designed to be sustainable and environmentally friendly. The concrete walls are intended to merge seamlessly into the surrounding lava field. They’re illuminated by exterior lights, set in the ground, which turn slowly, creating the illusion that the building itself is on the move, the walls billowing as if they were alive. The architect says he drew his inspiration from the rich history of the area, with its centuries-old belief in the supernatural – something that persists to this day.

From the outside, the building has a raw, bleak aesthetic, in keeping with the natural setting of glacier, lava field and mountains that inspired it. The interior, by contrast, looks more welcoming, judging from the online gallery, with simple designer furnishings and the highest-quality Jensen beds. In addition, the hotel is equipped with the very latest in smart technology, a detail that attracted Ari’s interest. Everything is controlled by app: the lights in the bedrooms, the temperature, the door locks and the pressure in the showers. Literally everything.

The scenery outside the car window is becoming ever more familiar. I know this route by heart, having driven it so often since I was a child. Every rock, hummock and hill has its name and its story. The mountain crags take on the shapes of creatures of folklore: the bigger rocks and mounds are populated by elves or huldufólk, ‘hidden people’, the mountains by trolls, the sea by mermen.

Of course, I know these stories are make-believe, relics from a past when people didn’t know as much as they do today, but part of me still clings to the belief that perhaps they actually knew more then, were more open to the world around them, their senses more acute.

Whenever I visit the Snæfellsnes peninsula and see the dome of the glacier looming at the end, the spine of jagged mountains, and the sheer rock stacks rising out of the sea, I can never quite shake off the feeling that we’re not alone.

Lea Snæberg

Mum turns round and points at a waterfall. Ari pretends like he’s interested, but I can’t be arsed to remind Mum that she’s shown us that waterfall a million times before and I know all about the story of the woman who sits there, combing her hair.

Checking my phone, I see that Birgir has written: Are you there yet?

No still in car, I reply. Will let you know when I get there.

I wait a while, but Birgir doesn’t reply, so I start wondering if it was stupid of me to say that. Why should he be interested in when I get there?

I scroll back through the photos I have of him. Birgir isn’t on social media much, but he sometimes sends me pictures that I save onto my phone. He’s a year older than me and we’ve known each other for several months. We’ve never actually met in real life, though, as he moved to Sweden when he was five and hardly ever visits Iceland. But his family are planning to come over at Christmas, so we’ll finally get to see each other then.

Although we’ve never met, I know a lot about Birgir, and he knows a lot about me, more than almost anyone else. I know he plays basketball and that his dog, Captain, always sleeps by his bed. And he wants to work with children when he’s older, either as a teacher or a sports coach. But I’ve never heard his voice and have no idea what he smells like, so I can’t imagine what it will feel like to meet him in real life at last, after everything we’ve shared with each other.

We’ve talked every day since we met online, and not just about trivial stuff. We’ve had deep conversations too, about what we want to do in life and about our feelings. Birgir’s the only person I’ve talked to about all the shit that happened at my old school. Like really