5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Dido Kent Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

Richmond, 1806. Miss Dido Kent has developed rather a taste for mysteries. Having solved the riddle of her niece's missing fiancé and the body in the bushes at Belsfield Hall, she is finding her quiet holiday at her cousin Flora's home rather unchallenging to say the least. So when a neighbour dies suddenly, leaving her entire estate to her young nephew, Miss Dido can't help but be suspicious. But is her over-active imagination making her look for murder where there is none? With dirty dealings and death amongst Richmond's upper classes, Miss Dido Kent is ideally placed to observe her neighbours' behaviour, and as she does so, she brings more to light than even she could have imagined.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 434

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

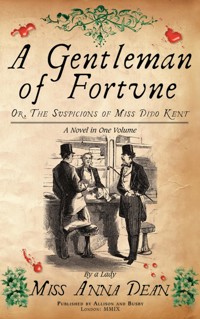

A Gentleman of Fortune

ANNA DEAN

For Mum, with love

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

About the Author

By Anna Dean

Copyright

Chapter One

Richmond, Wednesday 27th May 1806

My Dear Eliza

The great Mrs Lansdale is no more.

She was carried off on Tuesday night by a sudden seizure. It is a very heavy loss, for now the neighbourhood can no longer discuss the alarming symptoms of her nervous complaints, nor can it exclaim over every rumoured disagreement between the lady and her nephew.

However, it seems we are not done with Mrs Lansdale; she may yet provide a subject of conversation – for there is already an alarming rumour begun about her death.

Besides that half-pleasurable sorrow which is always felt at the death of a fine lady one hardly knows, there is a great distrust of the nephew. For it has not passed without notice that he has lost a remarkably tyrannical relation and gained a very fine inheritance.

Miss Dido Kent lifted her pen from the page and gazed beyond the little pool of light thrown by her candle, to the open window and the warm darkness beyond. She knew that she should not continue. What she was about to write was hardly proper. A letter should contain news but never gossip, and the great rule was to mention no person or event which could not be written about with charity.

But then, Dido mused with a smile, if the rule were adhered to too faithfully, letters would become so exceedingly dull that they would not be worth getting. They would scarcely justify their cost to the receiver.

And, besides, she had a very good reason for communicating this particular piece of gossip to her sister.

It is the odious Mrs Midgely who has begun this rumour. She has ‘the gravest doubts’ about Mrs Lansdale’s death. Mrs Midgely considers it as being altogether ‘too convenient’ for the nephew. In short, she believes that he took steps to hurry his poor aunt out of this world…

There! It was said. And very shocking it seemed now that it was written down.

Pleasedo not blame me for repeating this slander, Eliza. If you will only keep from throwing my letter aside in disgust – and will but continue reading to the end – I hope you will understand why I must write to you upon this subject.

You see, it all came out yesterday during Flora’s exploring party to the river.

And a very pleasant party it would have been, but for Mrs Midgely and her venomous conversation. Everyone was punctual, the sun shone upon us and there was an abundance of walking about, sitting down, fine views, pigeon pie and cold lamb.

Sir Joshua Carrisbrook was returned from town in time to join us – which pleased Flora greatly. And, by the by, itseems that what we had heard of Sir Joshua is true – he is to be married again, and very soon. And you may tell all his friends at Belsfield that he seems vastly contented – and in a great hurry to get to church! For, by his own account, the lady only gave her consent a week ago, but he is determined to be married before the end of another week and has got himself a special licence for that purpose. I suppose he does not wish to wear out what youth he may suppose remains to him in waiting a full three weeks for the banns to be called.

It is extraordinary to see a man of his advanced years so very much in love! And I could not but pity him; for he was so wanting to tell us all of how he was soon to become ‘the very happiest of men’ and to enumerate the many virtues and talents of his lady; and he had scarcely begun to describe her musical genius and had not spoken one word about whose music she chiefly plays, when his happiness was quite hurried out of the way by Mrs Midgely who was wanting to be talking herself.

So I confess that I remain in ignorance upon the important issue of whether the future Lady Carrisbrook delights most in concertos or in folk airs – and I cannot even tell you what her maiden name may be…

But, to return to Mrs Midgely and her suspicions. By her account, Mr Vane, the apothecary, is uneasy about Mrs Lansdale’s death. He says that, ‘there was nothing in Mrs Lansdale’s general condition to make him expect such a seizure as carried her off! Which,’ says Mrs Midgely, looking about at us all, with a very red face and a satisfied manner, ‘which, I think you will all agree, seems very odd indeed, does it not?’

‘Oh, but I do not know that it is so very odd!’

This mild protest came from little Miss Prentice – Mrs Midgely’s boarder – who seems to rent from Mrs Midgelynot only her back parlour but also a share in her right to spy upon all the grand people of the neighbourhood.

‘If I must give my opinion,’ says Miss Prentice – though no one there had asked for her opinion – ‘I do not think it is so very odd at all. It does sometimes happen that a person can be taken with a sudden attack such as they have never had before. For it happened to poor Lord…’

But Mrs Midgely had no patience to let her go on. For once Miss Prentice is begun upon lords and sirs there is no end of it.

‘Mr Vane,’ says Mrs Midgely, speaking very loud, ‘is very much puzzled by the lady’s death. And, in my opinion, he ought to take the appropriate steps.’ And she lowered her voice to a suitably portentous whisper. ‘I have told him that he must speak to the magistrates.’

And then we had all to listen to a great many accounts of what I had heard many times since coming to Richmond: of how Mrs Lansdale had demanded a great deal of attention from her nephew – on account of her many illnesses – that he had often wanted to ‘pursue his own pleasures’ in town, but had been restrained by her poor health and nervous disposition which would not permit her to be left alone. Mrs M was very eloquent upon these subjects – and no less so upon the subject of how ‘young men these days’ do not like to have their pleasures curtailed.

Well, Eliza, what I have not told you of yet, is how very distressed poor Flora was looking all the while that this was carrying on. For, you see, Mr Henry Lansdale, the nephew – this very gentleman that Mrs M was slandering – is a great favourite with our cousin. She and her husband met the Lansdales at Ramsgate last autumn and, though I have notyet been introduced to the young man, I have observed that she always speaks very highly of him.

I do not think Mrs Midgely knows of Flora’s connection with the Lansdales and believes them to be strangers to her, as they are to everyone else here in Richmond. At least I sincerely hope that she knows nothing of the friendship – or else she was being unpardonably rude to be talking so of her hostess’s acquaintances! (Though, in truth, I do not put anything beyond the licence that woman allows her tongue!)

However, I think that, maybe, Mrs Midgely’s ward, young Mary Bevan, was quick-witted enough to suspect the truth, from her gentle efforts to smooth things over. She pointed out, in her quiet precise way, that, ‘Mr Vane had been attending upon Mrs Lansdale for little more than a month,’ and suggested that, ‘he might not have a very accurate knowledge of all the poor lady’s disorders and symptoms.’

This did little to stop the abuse; but one must admire the real elegance of mind which prompted it; and one cannot help but wonder how such a pleasant, sensible girl can have been brought up by the dreadful Mrs M.

But, to return to Flora. She was close to tears by the time the carriages came, and she broke down completely in our journey home.

‘I cannot understand,’ she said again and again, ‘why Mrs Midgely should say such things! Why should she wish to malign poor Mr Lansdale? And why should she wish to persuade the apothecary to cause trouble for him? I have never known her be so very unkind before.’

And, in all honesty, neither can I understand it, Eliza. It is a level of interference and trouble-making far beyond the usual malice of gossip.

Poor Flora! She keeps to her room today with the headache which, I make no doubt, was brought on by yesterday’s distress. Her sufferings are, I believe, all the worse for being unfixed and uncertain; for neither she nor I can judge the exact degree of danger in which Mr Lansdale might stand – I mean if Mr Vane should yield to the tiresome woman’s advice and refer the matter to the magistrate. And, since Flora’s husband is still absent upon business in Ireland, we have no gentleman here to whom we can turn for advice upon such a delicate matter.

And this, my dear sister, is the reason for my troubling you with this most unpleasant business. It occurs to me that, since you are staying at Belsfield Hall, you might seek advice on our behalf. Would you be so kind as to ask Mr William Lomax…

Dido was forced, by the shaking in her hand, to stop writing.

There was already a blot spreading through her neat black words. And her cheeks were burning too. She laid down her pen and turned her face into the night air which was blowing in through the open window of her bedchamber, bringing with it the scents of roses and cut-grass and dew – and the high, shivering call of an owl from somewhere down beside the river.

She had thought that she had long outlived the age at which the mere writing of a gentleman’s name could bring a blush to her cheeks. Yet she could not help but wonder what Mr Lomax would think – how he would look – what he would say – when Eliza mentioned her name and her request.

Dido’s situation with regard to this gentleman was a particularly delicate one.

Mr William Lomax was the man of business who overlooked the running of her niece’s husband’s estate at Belsfield Hall. Last autumn, when she had been at Belsfield, Dido had come to esteem him very highly indeed and, before she was called away, she had been certain – almost certain – as certain as a lady can ever allow herself to be – that he returned her regard: that he was, in fact, only prevented from making a declaration by a want of wealth and independence.

Then she had been full of hope; sure that they could not be separated for ever; sure that the particular circumstances which kept him poor just then, could be removed. But now, after six months of hearing almost nothing of him, it was all but impossible not to be desponding: not to believe that her influence over him was weakening; not to calculate very exactly her five and thirty years, or to disregard the opinion of all her friends who had long reckoned her a settled old maid.

As she had once overheard her sister-in-law, Margaret, remarking: ‘An heiress may fairly look for a husband at any age. But a portionless woman had better give up all such thoughts when she is thirty, and spare her family the expense of going much into company. For it will all be wasted. Nothing will come of it.’

Until she had come to know Mr Lomax, Dido had been, if not quite content to be a spinster, then at least reconciled to it because she had never found in the usual round of dinners and balls and visits much temptation to change her state. But a remarkable set of circumstances had brought her together with Mr Lomax and authorised a kind of communication far beyond the usual littleness of social intercourse. She had learnt the pleasure of sharing ideas and confiding in a way which she had never known before. And now…

And now, as she sat beside the window of her bedchamber in Flora’s pleasant summer villa, she was beginning to suspect her own motives.

For, oddly enough, it had been a murder and the mystery associated with it which had first brought her together with Mr Lomax. So, was she now only taking an interest in this affair of Mrs Lansdale’s death because it was a means of bringing herself once more to the gentleman’s attention?

She smiled. Hers must be a very singular affection if it could only thrive upon infamy and mystery! But she would not allow one half of her to suspect the other. There could be nothing wrong in only asking a gentleman’s advice and, besides, she really did wish to discover the exact degree of danger in which Mr Lansdale stood.

Would you be so kind as to ask Mr William Lomax – for I know that he has a very thorough understanding of the law – whether, in his opinion, Mr Lansdale is in any danger? Might Mr Vane’s information lead the magistrates to bring a prosecution? And, if it should go so far, how heavily would the testimony of such a man as this apothecary tell against him? It cannot be denied that the young man has gained a great deal from his aunt’s death: if there was a suspicion of murder, would not that suspicion fall immediately upon him?

Flora is most anxious that we should somehow find a wayof putting an end to these dreadful rumours, before they have any serious consequences.

I agree that it ought to be attempted; but I cannot conceive how such a woman as Mrs Midgely is to be worked upon. I doubt she has ever, in the whole course of her life, held her tongue at someone else’s request. And she seemed to take such an inordinate pleasure in spreading her poison that I could not help but wonder whether she has some grudge or cause against the young man. Something which might make her particularly venomous in this case.

And I do not think we can silence her without first discovering her motive.

Chapter Two

Richmond, mused Dido as she walked to the post office with her letter next day, was a remarkably proper place. There was something particularly elegant and refined about the pretty little villas clustering around the river and up onto the hill, with their verandas and their French windows and their shady gardens. Maybe, she thought, it was this air of prosperity and tranquillity; the scent of syringa and lime trees; the sight of comfortable barouches and fashionable little landaulets driving by, which made the rumours Mrs Midgely was spreading so very shocking.

It certainly was a very strange, distressing business. This morning poor Flora was still suffering from nervousness and headache, and Dido’s resolve to silence Mrs Midgely and save Mr Lansdale from a dangerous slander was compounded as much of compassion as a strong desire for justice.

But, as she walked, she had to confess to herself that there might be another, secondary motive which was rather less virtuous. She could not help but feel it would be very pleasant indeed to have something to think about! For the unaccustomed leisure of the past week had left her mind quite remarkably empty.

It was, she acknowledged, extremely kind of her cousin to invite her to Richmond. For, although Flora had been considerate enough to solicit her company as a favour and to represent herself as in need of a companion while her husband was absent on business, Dido knew that the visit was intended to be a holiday. And never had she been more in need of a holiday; for the past winter had been spent attending upon a very young, very nervous sister-in-law and her new and sickly child.

However, Dido was beginning to suspect that unmarried women who were past their youth were not constitutionally suited to holidays and that the usual system of employing them to their families’ advantage as temporary, unsalaried nurses, governesses and nursery maids had more kindness in it than she had previously supposed.

While she had been in Hampshire, though Henrietta had been a no more rational companion than Flora, Dido had had little time to spare from the demands of colic and red-gum and the leaking of melting snow into the pantry, to notice the deficiency.

Here, in the luxury of Flora’s summer villa, she was nearer to suffering from ennui than she had ever been in her life before – and had, furthermore, too much time in which to remember the many perfections of Mr Lomax.

She stopped. She was come now to the substantial, redbrick bulk of the Lansdale’s house, and its closed shutters, its weedless gravel sweep and its sombre cedar tree seemed to throw an air of mourning across the hot afternoon. The gateposts were topped with imposing urns of stone and, on the left-hand post, there was a very fine, very new sign with the name of Knaresborough House carved in thick black letters. It looked remarkably respectable, and to imagine a murder taking place in such a house was all but impossible.

She stepped away, and, as she did so, she noticed that upon the opposite side of the road was Mrs Midgely’s villa – with little Miss Prentice watching from the back parlour window.

Dido paused, looking thoughtfully from one house to the other – and at the three or four yards of dusty road which was all that divided them. And she wondered… Perhaps the very proximity in which Mrs Midgely and Mr Lansdale lived had some bearing upon the case…

The post office was crowded: so very full of ladies and bonnets and gossip and little yelping lap-dogs that there was no one free to attend to Dido at the counter and she was obliged to wait. The room was confined and stuffy. Its small, dusty window and its dark panelled walls made it so very gloomy after the brilliance outside that at first she could recognise no one in the little crowd.

Then, after a moment or two, when her eyes had grown accustomed to the poor light, she saw that the young woman standing before her at the high counter was Mrs Midgely’s ward, Mary Bevan, enquiring after letters. A narrow ray of dusty sunlight falling through the office’s single high window was just catching the side of her fresh, delicate cheek, displaying the lovely long dark eyelashes to great advantage. And, as Mary turned away from the counter, putting a letter into her pocket, Dido could not help but wonder anew that so very elegant a creature should be the ward of such a vulgar woman as Mrs Midgely.

Miss Bevan smiled and began upon a gentle greeting, but her words were immediately lost in the loud throwing open of the door behind them and the bustling entrance of her guardian. Nearly everyone in the room turned to see who it was.

‘There you are Mary! I wondered where you were got to! And Miss Kent too, I believe,’ peering through the gloom. ‘Very pleased to see you, I’m sure Miss Kent.’

Mrs Midgely was a large woman of about fifty years old, dressed in yellow patterned muslin with a great many curls on her head and a great deal of colour in her broad cheeks. ‘Such a delightful exploring party yesterday,’ she continued. ‘I am sure we are all very much obliged to dear Mrs Beaumont for inviting us. You may tell her that she will soon receive a letter of particular thanks from me.’

Dido began upon a civil reply, but was not suffered to continue long. Mrs Midgely was just come from the haberdasher’s and so was full of news and delighted to have chanced so soon upon someone to whom she could tell it.

‘Well, Miss Kent,’ she burst out, ‘it seems it was the Black Drop that did the damage. Mrs Pickthorne says that Mr Vane says it was the Black Drop for sure.’

‘The Black Drop?’ repeated Dido.

Mrs Midgely smiled broadly and comfortably: sure of having her attention. ‘It was,’ she said loudly, ‘the Black Drop which killed Mrs Lansdale.’

There seemed to be a little quietness around them in the post office: a sense of listening. Dido noticed that poor Mary Bevan’s eyes were turned upon the floor and a blush of shame was creeping up her cheek. It seemed that years of experience had not inured the girl to the behaviour of her guardian.

‘And what,’ asked Dido, as quietly as she might, ‘what is the Black Drop?’

‘It is,’ announced Mrs Midgely, ‘a barbarous medicine, made in the north country, which Mrs Lansdale had got into the habit of using. The Kendal Black Drop it is called.’

‘Kendal?’

‘Kendal,’ said Miss Bevan quickly, ‘is a town in Westmorland – near Mrs Lansdale’s home – quite near to the Lake Country I believe. I wonder, Miss Kent, if you ever happened to read Mr West’s delightful Guide to the Lakes?’

It was a valiant attempt to turn the conversation but the poor girl might as well have held up her hand to halt a raging bull. There was no stopping her guardian from telling her news.

‘The Kendal Black Drop,’ she reiterated with great weight – and cast a withering look at poor Mary. ‘It is a stuff four times stronger than laudanum and it seems that poor Mrs Lansdale was quite addicted to its use.’

‘I see.’

‘And dear Mr Vane is sure that if she had but taken his advice and given it up, he could, in the end, have cured her of all her illnesses. For, you know, Miss Kent, he is a very clever man…’

‘And so, Mr Vane believes that it was her use of this medicine which brought on Mrs Lansdale’s seizure?’ said Dido more loudly. ‘What a very unfortunate accident.’

She attempted to step away to deal with her business at the counter, where there was now a vacancy. But so eager was Mrs Midgely to finish her tale that she laid a hand upon her arm.

‘Well,’ she continued in the same inconveniently loud voice. ‘It was the Black Drop killed her for sure. But a great deal of it. He is quite sure that she had drunk four times as much of the stuff as she should have done.’

‘Four times?’ echoed Dido. Internally she could not but admit it was a very large amount. But she only said, ‘how…regrettable.’

‘Well, what Mr Vane cannot understand is this: how did she come to drink so much all at once?’

‘I am sure,’ said Miss Bevan firmly, ‘that with so powerful and dangerous a medicine, an accident, though very sad, is hardly to be wondered at.’

‘Quite so,’ said Dido, hastily putting aside her own doubts.

‘Accident indeed!’ cried Mrs Midgely. But she had said all she wished to say and seemed well satisfied with the looks of interest she was receiving from the people around her. She allowed Dido to escape to the counter. ‘And did you get any letters?’ she asked Mary.

‘No, Ma’am, none at all.’

Dido turned back at the sound of the lie – and saw that it had brought another, brighter, blush to Mary’s cheeks.

Chapter Three

Next morning Dido accompanied Flora upon a visit of condolence to Henry Lansdale. She was very eager to meet him; reasoning that a man who could earn such affection from his friends and such malice from his neighbours, could not fail to be interesting.

It was another exceedingly hot day with not a cloud to be seen in the sky. Down beyond the river the hay was being cut and the scent of it carried right into the town. The two women walked slowly along the tree-shaded street.

‘I do not doubt,’ said Dido after walking for some time in silence, ‘from everything I have observed, that Mrs Midgely is a very malicious woman. But what I cannot yet quite determine is why her malice should be particularly directed against Mr Lansdale. Do you know of any reason why she should be his enemy?’

‘No, I do not!’ Flora Beaumont frowned prettily in the deep shade of her bonnet, her soft white nose wrinkling in a way which always put Dido in mind of a rabbit. ‘He is such a very delightful man. Why, I cannot conceive that he could have an enemy in the whole world! And besides, Mrs Midgely does not know him.’ Her lips puckered in a childish pout. ‘The Lansdales have been here but a month and Mrs Midgely is not even upon visiting terms with them, you know.’

‘Then perhaps she had heard something ill of him.’

‘But I have told you, there is nothing ill to hear! Nothing at all!’

‘There were, I understand, quarrels between aunt and nephew.’

‘Oh, but they were nothing! It was just her way.’ Flora paused in the shade of a tree, twisting one finger daintily in the long ribbon of her bonnet. ‘I rather fancy she liked to quarrel sometimes, you know. There was always a great making up afterwards.’

‘Perhaps,’ Dido suggested, trying her best not to injure her cousin’s sensitive feelings, ‘perhaps it is jealousy which turns Mrs M against him. He is after all so very fortunate – a poor young man taken in by his aunt, and now inheriting a great estate in Westmorland…’

‘Dido! Do not talk so! I cannot bear it. You sound so horribly suspicious.’

‘No, no,’ Dido assured her hastily. ‘I am not at all suspicious. I am only trying to understand why other people might be suspicious.’

‘Well!’ cried Flora, clapping her hands together. ‘I can tell you why such a woman as Mrs Midgely is suspicious. It is because she is spiteful and cruel…and horrid. And we must find a way to silence her. You must find a way, Dido. You are the clever one. The whole world is forever saying how very clever you are.’

‘I am sure I am very much obliged to the world for its good opinion. And I certainly intend to silence Mrs Midgely if I can. But…’

She stopped suddenly because they had come now through the gates of Knaresborough House and, as they started up the sweep, she had caught sight of something rather strange.

A young boy in a gardener’s smock was digging a hole beneath the great boughs of the cedar tree which stood close by the gate. As Dido and Flora watched, he thrust his spade into the pile of excavated earth, picked up a bundle wrapped in sacking and dropped it into the hole.

‘Oh dear!’ cried Dido, almost without thinking, ‘is that a grave you are making?’ Impelled by overwhelming curiosity, she hurried towards him, leaving Flora frowning upon the gravel.

The boy looked up, pushing damp hair out of his eyes. He was about twelve years old with fair, almost white hair and a drift of freckles across his cheeks and nose. ‘It is Sam, is it not?’ said Dido. ‘We met when you came to dig the new flower-bed in Mrs Beaumont’s garden. Do you remember?’

‘Oh yes, miss,’ he said with a smile. ‘I remember. You was very kind about that wasp sting.’

‘And today you are working for Mr Lansdale?’ Dido looked inquiringly towards the hole.

‘Yes miss,’ he said. ‘I’m burying Mrs Lansdale’s little dog.’

‘Oh? Indeed!’ said Dido with great interest.

‘Been dead nearly a week, miss. I’d not come any closer if I were you.’

She took a step back, for there was indeed a very unpleasant odour mixing with the scent of lilac and the dark smell of the cedar. ‘Nearly a week?’ She glanced anxiously back at Flora and calculated rapidly. ‘Then the dog died about the same time as Mrs Lansdale?’

Sam nodded. ‘They say he went missing the very night the old lady died. But they only found him this morning – dead and hidden in among the laurel bushes.’

‘I see. How strange.’ How very strange. She gazed thoughtfully at the gaping hole in the ground. Why should the dog die at the same time as his mistress? It seemed a remarkable coincidence – indeed it seemed a great deal more than a coincidence… ‘But,’ she said carefully, ‘they do say, do they not, that a dog will sometimes pine away when the person to whom he has been devoted dies?’

‘I don’t know about that, miss,’ said Sam. He too looked down at the open grave and rubbed the side of his nose, smearing dirt into the freckles. ‘It may be a dog’d pine away,’ he said slowly. ‘But I can’t see how any dog would be so heart-broke it’d crawl away into a bush and cut its own throat.’

‘Oh no, no indeed,’ said Dido as she turned away, ‘you are quite right. Quite right.’

‘I do not see,’ said Flora irritably, ‘why you should be so concerned about the death of a dog.’

‘But my dear cousin, it is of the greatest importance. For it would seem the dog died at the hand of man, and that must mean…’ She stopped herself. There was something so remarkably innocent about Flora’s childlike face – the wide blue eyes gazing at her in such a puzzled, unsuspecting way…

Dido shrugged up her shoulders and merely said, ‘Well it is very strange, is it not?’

But her thoughts were working rapidly. The dog had been killed. Why? Why should the animal meet its death at the very same time as its mistress…? Unless there had been dark forces at work here at Knaresborough House.

The great question must be: had the death of the lady been as unnatural as her pet’s? Dido found herself remembering the apothecary’s account of the large amount of opium mixture Mrs Lansdale had drunk. She could not help it; she was beginning to wonder whether there could be some truth in the rumours. Perhaps there was some agency at work here worse than the malice of gossip.

She approached the respectable red-brick front of Knaresborough House with increased interest – and more than a little suspicion.

A remarkably young and inexperienced maid opened the door to them. She was very unsure of herself. She was unsure of how many curtsies she should make; unsure of whether Flora was to be addressed as ‘Miss’ or ‘Madam’; unsure whether her master was at home. And then, having ascertained that he was at home, and that he would be ‘down directly’, she was very unsure indeed about which room the visitors should be shown into.

She stood for several moments in the spacious, white-painted entrance hall, looking anxiously from one closed door to another, her hands twisting clumsily in her apron. No superior servant appeared to advise her and Dido observed the scene with great interest, wondering how it came about that such a fine house should be so ill-served. She had expected a manservant to open the door – a fellow with a bit of dignity about him: and a footman perhaps in attendance too.

‘It had better be the drawing room, I think,’ said the girl at last, throwing open a door, ‘though it’s not been used or put to rights since the day before the mistress died and I hope you’ll excuse it not being aired.’

They walked into the room and Dido looked about her with great interest.

It was very gloomy from the blinds still being half-drawn, and the furnishings were as impersonal as those of any house that is offered to be let by the month – though very rich and substantial, as befitted one advertised as aspacious residence suitable to a gentleman of fortune. There was a wealth of solid mahogany furniture and silver candlesticks, a magnificent, steadily ticking wall clock, and sumptuous, over-long curtains of cream brocade which lay in folds upon the Axminster carpet; but there was little that spoke the character of the present occupants – except, perhaps, some pretty red shades which had been fitted over the candles by the hearth.

‘I believe,’ said Dido, turning to her cousin, ‘that, in general, it is possible to learn a great deal about our acquaintances from looking at their drawing rooms.’

‘Is it?’ Flora looked startled. It was not an idea that had ever come into her head before.

‘Though,’ Dido admitted as she began to walk about the room, ‘on the present occasion, I do not know that I can deduce much beyond the fact that Mrs Lansdale was a rather vain woman.’

‘Why do you say so?’

‘What other purpose is there in a red light but to flatter a woman’s face? And,’ she said, turning to the open pianoforte, ‘I see that she was a musical lady. And on the evening that she died she had been playing – or listening to…’ She took the sheet of music from the stand, ‘…Robin Adair.’

‘Oh no! You are quite wrong, you know,’ said Flora, following her across the room. ‘I have never in my whole life known such a very unmusical woman. She never played herself, and she quite hated to hear anyone else play.’

‘Did she? That is strange. But perhaps that is why there is no other music here. And yet,’ Dido added thoughtfully, ‘it seems someone has been playing: for here is the instrument open and the music set ready upon the stand…’

She picked up the sheet of music and studied it more closely. It was the usual kind of thing – to be found on music stands everywhere: paper bought from the stationers with the lines already ruled, but with notes and words filled in afterwards by hand. In this case certainly by a woman’s hand… Yes, most certainly a woman’s hand. The notes were drawn very neat and black and clear and the words were written in a pretty, flowing hand which put a great many twists and turns upon the letters – particularly upon the Ss and the Ws.

She put it down and crossed to the hearth, where her eye was caught by a mark upon the back of a chair. She touched it and found it to be sticky. She put her fingers to her nose and smelt pomade and powder.

‘Well,’ she said, ‘I would guess one thing about Mr Lansdale. I would guess that he puts powder in his hair.’

‘Indeed he does not!’ cried Flora, shocked at the suggestion. ‘Such a nasty, old-fashioned habit! My dear cousin, no gentleman under forty puts powder in his hair now!’

‘Well then, if you are quite sure, I think we may say that, on the evening of his aunt’s death, Mr Lansdale was visited by an ageing and unfashionable man…Or rather,’ she said, looking across at the chair on the opposite side of the hearth, and seeing a similar stain, ‘by two ageing and unfashionable men – one of whom was considerably taller than the other.’

‘Dido, now I am sure that you are making things up! How can you possibly know how tall the gentlemen were?’

‘By the places at which their heads rested upon the chairs. Look. Do you not see that one of the powder stains is much higher than the other?’

‘Oh yes! Why it is true, you are clever!’

‘Thank you.’ Dido turned aside knowing that she ought not to take so very much pleasure in the compliment.

As she turned, her eye fell upon the mantel shelf. There was a white and gold china shepherdess, thinly coated in dust, and a very fine pair of branching silver candlesticks – and, propped behind one of the candlesticks, there was a little bit of pasteboard. With a quick glance at the door to be sure they were not overlooked, she picked it up and read what was written on it…

She stared. Read it again. And then again a third time as if she could not quite believe what she had seen.

‘Flora,’ she said. ‘Mrs Midgely claims that she is unacquainted with the Lansdales – is that not so?’

‘Yes.’

‘She says she does not know them at all?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then she is lying.’ She held out the piece of pasteboard. ‘Look, here is her calling card.’

Flora’s little mouth dropped open in surprise. But before she could speak, there was a sound of heavy footsteps behind them.

‘I beg your pardon,’ said a very deep voice. The two women turned rather guiltily and saw, standing in the doorway, precisely the kind of manservant Dido had expected to find in this house: a very tall man – not many inches short of six feet in height – with a high-domed, bald head, an air of extreme dignity and a voice so low that it seemed to echo somewhere deep inside her.

‘I am sorry,’ he said, ‘there has been a mistake. Young Sarah should not have brought you into this room.’

‘Oh!’ cried Dido cheerfully. ‘Do not worry about us. We are quite comfortable here.’

‘I am very glad to hear it, miss.’ The man regarded her with solemn disapproval. ‘But it is not Mr Lansdale’s wish that this room should be used. If you will just step across into the breakfast room…’ he said.

And there was nothing for it but to put aside all thoughts and suspicions of Mrs Midgely for the moment and follow the manservant across the entrance hall into a smaller, sunnier apartment where they were soon joined by Mr Lansdale – and Miss Neville, the lady who had been Mrs Lansdale’s companion.

Henry Lansdale, she discovered, was a very handsome young man indeed. And as charming as Flora had made him out to be. He had lively blue eyes, a fine bearing, and a pleasant, unreserved manner. During the first ten minutes of the visit he behaved exactly as he ought upon receiving a visit of condolence. He ran through an account of his aunt’s death; explaining that she had retired to bed early on her last evening. She had been tired, he said, but they had had no reason to think she was at all in danger – until the housemaid discovered her dead in her bed next morning.

He expressed all the proper sentiments as he told this melancholy tale and spoke with very becoming simplicity – and great feeling. But Dido noted that he was not easy; he paced from the hearth to the window and was anxious and restless to a degree for which grief alone could not account.

As he talked, Miss Neville sewed and smiled.

Flora had explained to Dido that Clara Neville was a cousin of the Lansdales who had been living with her mother in Richmond in ‘very reduced circumstances’ before her grand relations came to Knaresborough House and she was invited to join them as a companion. She was a tall, bony woman of perhaps five or six and forty who could not, even in her youth, have been thought pretty – having rather more forehead and less chin than is usually considered desirable.

The smile which occupied her mouth was at odds with the deep lines of discontent and ill-humour on her brow. And, since her mouth was small and her brow wide, the discontent and ill-humour rather got the better of it.

Her speeches too were a mixture of perfunctory pleasantry and irrepressible discontent. She lamented the death of her cousin loudly, but Dido could not help but suppose that the loss of her own comfortable position was the saddest part of the business, from her, ‘I suppose I shall have to return to mother soon,’ following on almost immediately.

After a while there was a pause in the conversation and Dido took the opportunity to politely regret the death of the dog – watching Mr Lansdale closely for any sign of consciousness or guilt, as she spoke.

But he only seemed as puzzled as she was herself. ‘That,’ he said turning from the window at which he was standing, ‘is a very strange business indeed. I cannot account for it at all.’ He began to pace about the room once more.

‘Oh dear!’ cried Flora. ‘I am very sorry! We have raised a subject which distresses you.’

‘No,’ he said in a softened tone, ‘my dear Mrs Beaumont, please do not be uneasy on that score.’ He sat down beside her. ‘The subject does not distress me,’ he said very gently. ‘It merely puzzles me. I cannot get it out of my head. You see, I know the creature was alive at seven on the evening that my aunt died.’

‘Are you sure of that?’ asked Dido, rather more abruptly than she intended.

‘Oh yes,’ he said, ‘because I took it down to the kitchen at that time and fed it as I always did. Then I let it out to run about in the garden. It was still in the garden when I left at about half after seven to keep my evening engagement in town.’

‘You were from home that evening?’ asked Dido keenly.

‘Yes,’ he said looking at her in some surprise.

She blushed. ‘I am sorry. I only meant to say that I suppose you were not able to search for the dog.’

‘No, I was not. But Miss Neville was here all evening and she says that the butler, Fraser, searched the lawns and called for it. Did he not, Miss Neville?’

‘Oh!’ Miss Neville dropped her work and put her finger to her mouth. ‘I beg your pardon?’

‘I was telling Mrs Beaumont and Miss Kent about the little dog. He was searched for during the evening, was he not?’

‘Oh yes. Yes. Several times.’

‘I see,’ said Dido, with her eyes fixed upon a little spot of fresh blood on the white linen lying in Miss Neville’s lap.

‘And I suppose,’ she said, carefully, ‘I suppose you have asked everyone who visited that evening whether they saw the dog?’

‘There were no visitors that day,’ said Mr Lansdale unhesitatingly. ‘Nor had there been for some days past.’

‘Were there not?’ said Dido with some surprise, remembering the signs of company which they had found in the drawing room.

‘Oh no,’ said Mr Lansdale, ‘we kept hardly any company.’

Dido could not let the opportunity pass her by. ‘Did you not?’ she said, her mind upon Mrs Midgely’s calling card. ‘Your aunt was not upon visiting terms with any of her neighbours?’

‘Oh no. They were not such people…’ He stopped himself and smiled. ‘My aunt, you see, was very particular about the company she kept. It is an invalid’s privilege, is it not?’

‘And of course,’ added Miss Neville in her whining voice, ‘we were not allowed visitors on account of her nerves… Though I am sure,’ she added hastily, bending over her work once more, ‘for my own part I did not mind it one bit. It is much pleasanter to be private, is it not?’

There was another short silence which was broken by Mr Lansdale’s sighing. ‘I am grateful,’ he said feelingly, ‘that my poor dear aunt never knew what had happened to the pug. She was extremely fond of the animal.’

‘Oh dear yes! I am sure you all were,’ cried Flora politely.

He made a strange noise and covered his face with his hand. It almost seemed that he might be smothering a laugh.

At the same time Miss Neville’s grating voice burst out with: ‘Yes, to be sure it is a very great pity. My poor cousin would have been quite heart-broke… Though it was not a nice little dog – barking away every time there was a knock on the house door. And it bit me once. I only picked up and returned a length of sewing cotton which Mrs Lansdale had dropped, and it bit me! And I am sure the servants disliked it too. I doubt there is one of them who has not been bitten by it.’

‘Do you think perhaps one of them…?’ began Dido.

‘No,’ said Mr Lansdale quickly. ‘Its death would have upset my aunt to such a degree…put her into such a passion. She would…’ He recollected himself again and stopped. ‘I am sure you understand, Miss Kent, that the state of the mistress’s temper must be of the first importance to her servants.’

‘Yes, of course,’ said Dido, noticing once more his determination to always speak of his aunt with respect – and the effort which it sometimes cost him. She did not doubt that the lady had been just as difficult to defer to when she was alive.

Mr Lansdale drummed his fingers on the side of his chair for a moment. Miss Neville continued to sew and smile. But there was something uncomfortable about her smile which Dido could not understand.

Nor could she quite form an opinion of Mr Lansdale. He seemed all handsome appearance and proper feeling; but how deep this manly beauty went – whether it was a matter of person and manner only, or whether it was rooted in his character, she could not yet tell.

He was certainly unreserved. He had, while talking about his aunt’s death, already alluded to the unkind gossip concerning him and now, after sitting thoughtfully for a few moments, he gave a wry smile. It seemed his youth and high spirits could not long be held in check even by death and danger. ‘What I cannot quite determine,’ he said, ‘is whether the death of the dog will exonerate me in the eyes of my neighbours, or whether it will confirm me a murderer.’

‘A murderer!’ cried Flora. ‘How perfectly horrid! I beg you will not say such things.’

But Dido held his gaze and said quietly. ‘Yes, Mr Lansdale, I am finding that point difficult to settle myself.’

The remark served to fix his attention upon her. Until that moment she had been only the lovely Mrs Beaumont’s poor cousin; but now, all at once, she had an existence of her own.

‘Miss Kent!’ he cried, smiling, ‘I do believe that you suspect me!’

Flora hastened to assure him that her cousin had no such doubts, that it was just too horrid for words to even suggest it.

But Dido waited until she had finished speaking and then, finding that the young man was still regarding her with slightly raised brows and shining eyes full of questions, she said, very seriously, ‘No, Mr Lansdale. Upon consideration I do not think that I suspect you. From what you have told me, the evidence seems to be in your favour.’

He shook his head and became suddenly solemn. ‘I am very glad to find that I have your good opinion, Miss Kent – and,’ turning with a softened voice, ‘yours too Mrs Beaumont.’ He sighed deeply. ‘And you are quite right. Those who can suspect me of lacking affection for my aunt quite mistake the matter.’ He paused again. ‘If I am guilty of anything,’ he said with great feeling, ‘it is certainly not a lack of affection.’

It was said very quietly, very properly and Dido did not doubt he meant to convey regard and respect for his dead relation. But, all the same, she could not quite like the way in which his gaze fell upon Flora as he spoke.

It started a new – and entirely unwelcome – suspicion in her head.

Chapter Four

‘“Something”,’ said Dido thoughtfully as the door of Knaresborough House closed behind them, ‘“something is rotten in the state of Denmark”.’

‘Is it?’ said Flora anxiously. ‘I am very sorry to hear it… But what has Denmark to do with us?’

‘It is a quotation from Shakespeare,’ Dido explained. ‘It is said by…one of his characters, in…one of his plays.’

‘Oh, that is all right then.’

‘I meant that, in the present case, for “Denmark” we should substitute “Richmond”.’

‘Oh yes! “Something is rotten in the state of Richmond”,’ Flora mused. She looked about her at the smooth lawns and the raked gravel of Knaresborough House, and, beyond the sweep gates, the new-built villas which lined the hill, sloping down to the slow, wide river with its willows and hayfields. A heat haze shimmered over everything and all was still but for one fashionable gig driving past at a smart pace, its high yellow wheels a blur of dust and speed. It all appeared very ordinary and proper. The warm air was full of the scents of hay and lilac – and still, just a hint of that other, less pleasant smell. Flora looked towards the cedar tree and the raw grave beneath it. ‘Yes! Of course!’ she cried. ‘“Something is rotten”. Yes, I quite see what you mean. Something is very rotten.’

‘No, no,’ said Dido, ‘I did not mean that. I meant to say that something strange is carrying on here. Something is wrong. Very wrong indeed.’

‘Oh. Is it?’ Flora considered a moment. ‘It certainly is strange that Mrs Midgely’s card should be in the drawing room.’

‘Yes, it would seem that there is, after all, an acquaintance of some kind between the two families. Is it, I wonder, the cause of Mrs M’s vehemence against Mr Lansdale? And, besides the card, there are the other evidences of visitors – of powdered gentlemen and a lady who played upon the pianoforte – on the very evening before Mrs Lansdale died. Altogether it would seem that Mrs Lansdale was much better acquainted with her neighbours than we have been led to suppose.’

‘But Mr Lansdale said that she did not receive calls – that there had been no visitors for many days.’

‘Yes. Precisely so,’ said Dido, pacing along the gravel. ‘And the great question must be – was he lying when he said…?’

‘No!’ cried Flora, hurrying after her, in a flutter of muslin and anxiety. ‘No, no, you must not say such things! You have seen him, Dido. How can you suppose such a man capable of a falsehood? There is truth in all his looks!’

‘Well, well,’ said Dido, unconvinced by this powerful argument, but reluctant to press the point. ‘Maybe he knew nothing about the visitors. After all he was absent on the fateful evening. And it may be that his aunt was quite in the habit of receiving secret calls.’

‘Yes,’ said Flora firmly, ‘it may.’

Dido judged it best to say no more of Mr Lansdale. ‘However,’ she pointed out, ‘one thing is certain: Miss Neville must have known about the visitors. She was at home all evening.’

‘Miss Neville may be lying,’ suggested Flora.

‘She may indeed, for she has not a handsome face to prevent her telling falsehoods.’ Dido threw her cousin a sidelong look as she spoke.

But Flora was thinking and twisting her finger in her bonnet’s ribbon. The result of her musing was: ‘I do not like Clara Neville. She has a nasty, unhappy look.’