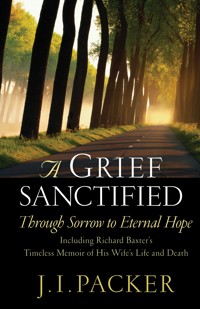

A Grief Sanctified (Including Richard Baxter's Timeless Memoir of His Wife's Life and Death) E-Book

J. I. Packer

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crossway

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

Their love story is not one of fairy tales. It is one of faithfulness from the beginning through to its tragic ending. Richard and Margaret Baxter had been married only nineteen years before she died at age forty-five. A prominent pastor and prolific author, Baxter sought consolation and relief the only true way he knew- in Scripture with his discipline of writing. Within days he produced a lover's tribute to his mate and a pastor's celebration of God's grace. It is spiritual storytelling at its best, made all the more poignant by the author's unveiling of his grief. J. I. Packer has added his own astute reflections along with his edited version of this exquisite memoir that considers six of life's realities-love, faith, death, grief, hope, and patience. He guides you in comparing and contrasting the world's and the Bible's ideals on coping with these tides of life. The powerful combination of Packer's insights and Baxter's grief gives you a beacon if you are searching for God, a pathfinder for your relationships, and a lifeline if you are grieving.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 283

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2002

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A Grief Sanctified

Copyright © 2002 by J. I. Packer

Published by Crossway Books a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers 1300 Crescent Street Wheaton, Illinois 60187

Originally published in 1997 by Vine Books, an imprint of Servant Publications.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided by USA copyright law.

Cover design: David LaPlaca

Cover photo: GettyOne Images

First printing 2002

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Packer, J. I. (James Innell) A grief sanctified : through sorrow to eternal hope : including Richard Baxter’s timeless memoir of his wife / J. I. Packer.

p. cm. Originally published : Ann Arbor, Mich. : Vine Books, c1997. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-58134-440-6 1. Baxter, Richard, 1615-1691. Breviate of the life of Margaret, daughter of Francis Charlton . . . and wife of Richard Baxter. 2. Baxter, Margaret Charlton, 1636-1681. 3. Dissenters, Religious—England— Biography. 4. Spouses of clergy—England—Biography. 5. Baxter, Richard, 1615-1691. 6. Puritans—England—Doctrines—History— 17th century. 7. Grief—Religious aspects—Christianity.8. Love—Religious aspects—Christianity. 9. Marriage—Religious aspects—Christianity. 10. Death—Religious aspects—Christianity.I. Baxter, Richard, 1615-1691. Breviate of the life of Margaret, daughter of Francis Charlton . . . and wife of Richard Baxter. II. Title.BX5207 .B3 P33 2002248.8'66'092—dc21 2002006708

PG 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09

15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

For Monty and Rosemary and for Kit again

CONTENTS

Prologue: To the Reader

PART ONE

Great Gladness: Margaret with Richard

Two Puritans

PART TWO

Great Goodness: Richard Recalls Margaret

To the Reader

1 Of Her Parentage and the Occasion of Our Acquaintance

2 Of Her Conversion, Sickness, and Recovery

3 Of the Workings of Her Soul In and After This Sickness

4 Some Parcels of Counsel for Her Deliverance from This Distressed Case, Which I Find Reserved by Her for Her Use

5 Her Temper, Occasioning These Troubles of Mind

6 Of Our Marriage and Our Habitations

7 Of Her Exceeding Desires to Do Good

8 Of Her Mental Qualifications and Her Infirmities

9 Of Her Bodily Infirmities and Her Death

10 Some Uses Proposed to the Reader from This History, as the Reasons Why I Wrote It

Appendix: Two Poems from Poetical Fragments (1681)

PART THREE

Great Sadness: Richard Without Margaret

The Grieving Process

Epilogue: To the Reader, Once More

Notes

PROLOGUE

To the Reader

Grief

This is a book for Christian people about six of life’s realities—love, faith, death, grief, hope, and patience. Centrally, it is about grief.

What is grief? It can safely be said that everyone who is more than a year old knows something of grief by firsthand experience, but a clinical description will help us to get it in focus. Grief is the inward desolation that follows the losing of something or someone we loved—a child, a relative, an actual or anticipated life partner, a pet, a job, one’s home, one’s hopes, one’s health, or whatever.

Loved is the key word here. We lavish care and affection on what we love and those whom we love, and when we lose the beloved, the shock, the hurt, the sense of being hollowed out and crushed, the haunting, taunting memory of better days, the feeling of unreality and weakness and hopelessness, and the lack of power to think and plan for the new situation can be devastating.

Grief may be mild or intense, depending on our own emotional makeup and how deeply we invested ourselves in relating to the lost reality. Ordinarily, the most acute griefs are felt at times of bereavement, when old guilts and neglects come back to mind, and thoughts of what we could and should have done differently and better come hammering at our hearts like battering rams. When Shakespeare’s Romeo said, “He jests at scars, that never felt a wound,” he was thinking of the pangs of eros, but his words apply equally to the pangs of grief. Grief is thus, as we say, no laughing matter; in the most profound sense, it is just the reverse.

Bereavement, we said—meaning the loss through death of someone we loved—brings grief in its most acute and most disabling form, and coping with such grief is always a struggle. Bereavement becomes a supreme test of the quality of our faith. Faith, as the divine gift of trust in the triune Creator-Redeemer, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, and so as a habit implanted in the Christian heart, is meant to act as our gyroscopic compass throughout life’s voyage and our stabilizer in life’s storms. However, bereavement shakes unbelievers and believers alike to the foundations of their being, and believers no less than others regularly find that the trauma of living through grief is profound and prolonged. The idea, sometimes voiced, that because Christians know death to be for believers the gate of glory, they will therefore not grieve at times of bereavement is inhuman nonsense.

Grief is the human system reacting to the pain of loss, and as such it is an inescapable reaction. Our part as Christians is not to forbid grief or to pretend it is not there, but to maintain humility and practice doxology as we live through it. Job is our model here. At the news that he had lost all his wealth and that his children were dead, he got up and tore his robe and shaved his head. Then he fell to the ground in worship and said, “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked I will depart. The LORD gave and the LORD has taken away; may the name of the LORD be praised” (Job 1:21 NIV). Managing grief in this way is, however, easier to talk about than to do; we are all bad at it, and for our own times of grieving we need all the help we can get.

At the heart of Richard Baxter’s grief book is an object lesson in what we may properly call grief management. Here we shall meet a grieving husband memorializing the soul mate whom, after nineteen years of marriage, he had tragically lost less than a month before. Margaret Baxter died at age forty-five after eleven days of delirium, her reason having almost wholly left her, as she had long feared it might do. A starvation diet had weakened her, and the barbarous routine of bloodletting, the universal seventeenth-century remedy for all disorders, had done her the reverse of good. A modern reader might guess that menopausal troubles were involved in her decline, but in her day the medical realities of menopause were unknown country.

Richard, her husband, twenty years older and a knowledgeable amateur physician, thought it was what she took over a period of time for her health (“Barnet waters” from Barnet spa north of London and “too much tincture of amber”) that brought on her death.1 “In depth of grief,”2 “under the power of melting grief,”3 Baxter resolved to write of her life, and within days produced a gem of Christian biography. It is at once a lover’s tribute to his fascinating though fragile mate and a pastor’s celebration of the grace of God in a fear-ridden, highly strung, oversensitive, painfully perfectionist soul. Baxter’s narrative is a classic of its kind and will help us in all sorts of ways.4

In 1681, when Richard wrote this Breviate (meaning “short account”) of Margaret’s life, he was probably the best known, and certainly the most prolific, of England’s Christian authors. Already in the 1650s, when despite chronic ill health he masterminded a tremendous spiritual surge in his small-town parish of Kidderminster, he had become a best-selling author and had produced enough volumes of doctrine, devotion, and debate to earn himself the nickname “Scribbling Dick.” Debarred in 1662 from parochial ministry by the unacceptable terms on which the Act of Uniformity reestablished the Church of England, he made writing his main business. By 1680, when he reached sixty-five, he had more than ninety publications to his name.

Then within six months came four bereavements.

In December 1680 “our dear friend” John Corbet, also an ejected minister and a close comrade of forty years’ standing, died. Corbet and his wife had lived in the Baxters’ home from 1670 to 1672. Baxter’s funeral sermon for Corbet testifies to their affection for each other,5 as did Margaret’s immediate persuasion of his widow to move back into the Baxter home on a permanent basis to be her personal companion.

Next, two members of what Richard called his “ancient family” finished their course: Mary, his stepmother, his father’s second wife, who had been living with them for a decade and had reached her mid-nineties, and “my old friend and housekeeper, Jane Matthews,” who had presided over his bachelor parsonage in Kidderminster and was now in her late seventies.

Finally on June 14, 1681, Margaret’s own life ended. As a pastor Baxter was, of course, used to dealing with deaths, but the cumulative strain of these four losses must have been considerable.

It should not surprise us that the distressed widower turned to a literary project for consolation and relief. He wrote very easily, and the writer’s discipline of getting things into shape is always therapeutic at times of emotional strain. Margaret’s will had called for a new edition of Baxter’s funeral sermon for Mary Hanmer (formerly Charlton), Margaret’s own mother. Baxter’s first thought was to bring out a volume in which he would prefix to that sermon four “breviates”—short lives of Mary Hanmer, Mary Baxter, Jane Matthews, and Margaret. Friends, however, persuaded him to drop the first three and cut out many personal details from his draft of the life of Margaret. “He was ‘loath to have cast by’ these ‘little private Histories of mine own Family,’ but he was ‘convinced’ by his friends . . . that his love and grief had led him to overestimate the value to others of what affected him so nearly.”6 Much, therefore, that we late-twentieth-century romantics, with our almost indecent interest in private lives, would like to know about “the occasions and inducements of [their] marriage” is lost to us. Nonetheless, the Breviate that finally emerged “is undoubtedly the finest of Baxter’s biographical pieces,”7 and one hopes that writing it benefited him as much as reading it can benefit us.

The personal memoir with a spiritual focus, a literary category pioneered by Athanasius’ Life of Antony and Augustine’s Confessions, was much more in evidence among the people of the Reformation after the mid-sixteenth century, Beza’s Life of Calvin and the stories of the martyrs in Foxe’s Acts and Monuments being among the more impressive examples. The seventeenth-century fashion of writing “characters”—literary profiles of human types and of particular individuals, viewed in lifestyle terms—further honed Puritan biographical skills. Baxter’s Breviate, though low-key and matter-of-fact in style, is Puritan spiritual storytelling at its best—storytelling that is made more poignant by Richard’s intermittent unveiling of his grief as he goes along. More will be said about this in due course.

C. S. Lewis’s Grief Book

“Mere Christianity”—meaning historic mainstream, Bible-based discipleship to Jesus Christ, without extras, omissions, diminutions, disproportions, or distortions—was Baxter’s own phrase for the faith he held and sought to spread. Three centuries after his time, C. S. Lewis used the same phrase as a title for the 1952 book in which he put together three sets of broadcast talks on Christian basics. Probably Lewis got the phrase from Baxter,8 and certainly in likening what he offered to the shared hallway off which open the rooms of the various denominational heritages,9 he was saying something very Baxterish. Lewis and Baxter belong together as men with a common purpose as well as a common faith.

Now Lewis, like Baxter, also lost his wife in his sixties, and while in the grip of grief turned to writing—the end product being his justly admired A Grief Observed. “After her [his wife’s] death in July 1960,” wrote Lewis’s friend and biographer George Sayer, “he felt both paralyzed and obsessed. . . . To liberate himself, he did what he had done in the past—he wrote a book about it, a book that is very short and desperately truthful. . . . In it he is trying to understand himself and the nature of his feelings. It is analytical, cool, and clinical.”10

Baxter too is analytical, cool, and clinical, but about Margaret rather than himself, and this sets the two books in interesting contrast. Lewis’s “breviate” of his bereavement experience has been widely seen as a model for Christian grief-narrative books, several of which have appeared in recent years,11 and this gives the contrast significance as well as interest. We shall reflect on this contrast in our final section.

For the moment, however, C. S. Lewis must wait in the wings. It is Richard and Margaret Baxter who stand center stage. Our Prologue has done its job of introducing, and now we must move on to where our story really starts.

PART ONE

GREAT GLADNESS:Margaret with Richard

RICHARD BAXTER

MARGARET CHARLTON

TWO PURITANS

Richard (1615-91)—evangelist, pastor, and tireless writer of devotional and controversial theology—and Margaret (1636-81), his wife, were Puritans. That means they were gloomy, censorious English Pharisees who wore black clothes and steeple hats, condemned all cheerfulness, hated the British monarchy, and wanted the Church of England and its Book of Common Prayer abolished—right?

Wrong—off track at every point! Start again.

Richard and Margaret came of land-owning families. Adult members of these families were called gentlemen and gentlewomen; they formed England’s aristocracy, as distinct from the laborers, tradesmen, and professionals (lawyers, physicians, clergy, and educators). Richard’s father, Richard Baxter senior, was a very minor gentleman with a small, debt-laden estate at Eaton Constantine in Shropshire. Margaret’s father, Francis Charlton, Esquire, was a more significant gentleman, a leading justice of the peace and a wealthy man. Margaret grew up in Apley Castle, less than four miles from Eaton Constantine. One of the traumas of her childhood was the demolition of the castle by Royalist troops in 1644 during the Civil War.1

Richard first met Margaret when she came to Kidderminster (in Worcestershire, next county to Shropshire) to be with her godly mother, now Mrs. Hanmer. Having been widowed a second time, Margaret’s mother had moved there to receive the benefit of Richard’s magnificent ministry. Kidderminster was an artisan community of some eighteen hundred adults, with weaving as its cottage industry. Half the town crowded into church every Sunday, and many hundreds had professed conversion.

Margaret was a frivolous, worldly minded teenager when she arrived, and at first she disliked both the town and the piety of its inhabitants. But a sermon series on conversion that Baxter preached in 1657 set her seeking a change of heart and a total commitment to devoted, penitent, Christ-centered worship and service of God. In due course she found herself assured of her sincerity in this commitment, and thus of her new birth, pardon for sin, and title to glory. Eagerly she took her place among Baxter’s working-class converts. But then she sickened, and for months seemed to be mortally ill with lung problems that nothing would relieve. Special intercession with fasting for her life by Baxter and his inner circle of prayer warriors resulted, however, in a sudden cure “as it were by nothing”—a healing that today would be called miraculous, one of several such in Kidderminster in Baxter’s time.2

Mrs. Hanmer’s home was a large, war-damaged house alongside the churchyard, where she “lived as a blessing amongst the honest poor weavers . . . whose company for their piety she chose before all the vanities of the world.”3 It is clear that Pastor Richard was often in her home, and Margaret, who found it difficult to discuss her spiritual problems with her mother, depended heavily on him for what we would call spiritual direction. One thing led to another, and when in April 1660, right after the day of thanksgiving for Margaret’s healing,4 he left for London for an indefinite period to play his part in the forthcoming restoration of the Church of England,5 she found herself wanting to follow him. Soon her mother and she had relocated in London where Mrs. Hanmer died of fever in 1661.

Baxter omitted from his memoir of Margaret “the occasions and inducements of our marriage,”6 but it is not hard to put two and two together. By the end of 1661 Baxter, who had always urged that the combined claims of marriage and parish were more than any clergyman could really meet, knew that his Kidderminster ministry was over, that there was no prospect of future parochial ministry for him,7 and thus that his case for clerical celibacy no longer applied to himself. Facing a future in which he expected writing to be his main ministry, he needed a home and someone to look after both him and it—for, by his own admission, he knew little of matters domestic and did not want to be bothered with them.

Meantime, now that her mother was dead, Margaret was alone in the world, and it seems clear that she knew she wanted to be Baxter’s wife, just as more than a century before, Katherine von Bora had wanted to be Luther’s. It is a natural guess that Mrs. Hanmer let it be known that she would like such a marriage to happen. Who knows what she said to Baxter when he was with her in what from the start she expected to be her last illness? At all events, an official license was issued on April 29, 1662, and the ceremony took place on September 10, after “many changes . . . stoppages . . . and long delays.”8 Then followed nineteen years of happy life together, till Margaret died.

And what about their Puritanism? Both were confessedly Puritans to their fingertips. The Puritanism of history was not the barbarous, sourpuss mentality of time-honored caricature, still less the heretical Manicheism (denial of the goodness and worth of created things and everyday pleasures) with which some scholars have identified it. It was, rather, a holistic renewal movement within English-speaking Protestantism that aimed to bring all life—personal, ecclesiastical, political, social, commercial, family life, business life, professional life—under the didactic authority and the purging and regenerating power of God in the Gospel to the fullest extent possible. This meant praying and campaigning for thorough personal conversion, consecration, repentance, self-knowledge, and self-discipline; for more truth and life in the preaching, worship, fellowship, pastoral care, and disciplinary practice of the churches; for dignity, equity, and high moral standards in society; for philanthropy, generosity, and a Good Samaritan spirit in face of the needs of others; and for the honoring of God in home life through shared prayer and learning of God’s truth, maintaining decency, order, and love, and practicing “family government” (a Puritan tag phrase) according to the Scriptures.

The “heart-work” that was central to Puritan piety—self-examination, self-condemnation, self-motivation, self-dedication, and the continual focusing of faith, hope, and love on the Lord Jesus Christ— had nothing morbid or self-absorbed about it; it was simply the inner reality of disciplined devotion. As Baxter himself never tired of urging, cheerfulness and joy—set in a frame of faith, humility, watchfulness, and obedience (“duties”)—are of the essence of the true Christian life. This was the Puritanism that Richard and Margaret sought to live out.9

Puritan Marriage

The Puritans called for the sanctifying of all relationships as an integral part of one’s service to God. The rule for sanctifying anything was Scripture. What was the Puritan ideal for holy wedlock? “The serious divine Richard Baxter is united in marriage to a young Puritan lady of aristocratic birth, a woman of fine mind, deep spiritual experience and kindred Puritan sympathy.”10 What did they understand themselves to be taking on?

The question is not hard to answer, for the evidence is plentiful and homogeneous.11 Abundant printed treatises and wedding sermons all tell the same story. The Puritans do not appear as post-Christian moderns whose thinking stops short at physical attraction, sexual satisfaction, and parental fulfillment (cuddles, orgasms, and babies, to put it bluntly). Nor do they appear as Victorian sentimentalists, dwelling entirely on the beauty of rose-colored rapport between souls, with bodies right out of the picture. W. J. Wilkinson sounds very Victorian when he writes of Richard and Margaret as “two souls who love God and love each other with that sublime, spiritual beauty in which souls are wed, which gives orientation to life and is eternal,”12 and quotes Browning to ram the idea home.

To be sure, there is real truth in the Victorian vision, just as there is real truth in the physicality of the modern conception, but neither perspective is theological enough to find the Puritan wavelength.

Nor, again, do the Puritans appear as eighteenth-century evangelicals, ruthlessly denying that the “foolish passion which the world calls love” should influence the godly man’s choice of a wife.13 “I know you must have love to those that you match with,” writes Baxter, and his only proviso is that it must be “rational” love that discerns “worth and fitness” in its object, as distinct from “blind . . . lust or fancy.”14

So how, in positive terms, did the Puritans conceive of marriage? They saw it as a gift, a calling, a task, and a lifelong discipline, and programmed themselves for it accordingly. What this meant is well shown us in Richard’s own monumental Christian Directory, to which we now turn.

First published as a three-inch-thick folio in 1673, this work is rather more than a million words long. Its title page reads: A Christian Directory: or A Sum of Practical Theology, and Cases of Conscience. Directing Christians How to Use their Knowledge and Faith; How to Improve All Helps and Means, and to Perform All Duties; How to Overcome Temptations, and to Escape or Mortify Every Sin. In Four Parts. I. Christian Ethics (or Private Duties). II. Christian Economics (or Family Duties). III. Christian Ecclesiastics (or Church Duties). IV. Christian Politics (or Duties to Our Rulers and Neighbors). (Remember that in the days before dust jackets and blurbs, title pages had to be fulsome, since it was only there that a prospective buyer could find information as to what was in the book.)

Richard’s magnum opus should be better known than it is, for it is truly a landmark, a full-scale compendium of Puritan moral and practical theology in all its many-sided devotional, pastoral, life-embracing, and community-building strength. Part II of this magisterial distillation of Puritan wisdom is subtitled “The Family Directory, Containing Directions for the True Practice of All Duties Belonging to Family Relations, with the Appurtenances.”15 Here Richard discusses, among other things, first, how a man should determine before God whether and whom to marry, and, second, the “duties” (mutual obligations) of husband and wife within the marriage relationship. These sections are of special interest, not only because Baxter is here creaming off the wisdom of a century of Puritan discussion as tested and verified in a busy fifteen-year pastorate, but because he wrote them in 1664-65, two or three years into his own marriage, the experience of which was bound to color his thinking. What, now, does he have to say?

“Marriage,” declares the Westminster Confession, XXI:2, “was ordained for the mutual help of husband and wife, for the increase of mankind with a legitimate issue, and of the church with a holy seed, and for preventing of uncleanness.” Baxter assumes this throughout. Who then should marry? Minors for whom marriages were arranged by their parents;16 persons with incontinent hearts, as directed in 1 Corinthians 7:9;17 and any in whose case it appears “that in a married state, one may be most serviceable to God and the public good.”18 But go into it with your eyes open! “Rush not into a state of life, the inconveniences of which you never thought on.”19 Baxter lists twenty “inconveniences,” of which the most striking are these:

• Marriage ordinarily plungeth men into excess of worldly cares. . . .

• Your wants in a married state are hardlier supplied, than in a single life. . . . You will be often at your wit’s end, taking thought for the future. . . .

• Your wants in a married state are far hardlier borne than in a single state. It is far easier to bear personal wants ourselves, than to see the wants of wife and children: affection will make their sufferings pinch you. . . . But especially the discontent and impatiences of your family will more discontent you than all their wants. . . .

• By that time wife and children are provided for, and all their importunate desires satisfied, there is nothing considerable left for pious or charitable uses. Lamentable experience pro-claimeth this. . . .

• And it is no small patience which the natural imbecility [weakness] of the female sex requireth you to prepare. . . . Women are commonly of potent fantasies, and tender, passionate, impatient spirits, easily cast into anger, or jealousy, or discontent. . . . They are betwixt a man and a child. . . . And the more you love them, the more grievous it will be to see them still [constantly] in discontents . . . .

• And there is such a meeting of faults and imperfections on both sides, that maketh it much the harder to bear the infirmities of others aright. . . . Our corruption is such, that though our intent be to help one another in our duties, yet we are apter far to stir up one another’s distempers. . . .

• There is so great a diversity of temperaments and degrees of understanding, that there are scarce any two persons in the world, but there is some unsuitableness between them. . . . Some crossness there will be of opinion, or disposition, or interest, or will, by nature, or by custom and education, which will stir up frequent discontents. . . .

• And the more they [husband and wife] love each other, the more they participate in each other’s griefs. . . .

• And if love make you dear to one another, your parting at death will be the more grievous. And when you first come together, you know that such a parting you must have; through all the course of your lives you may foresee it.20

If, having weighed all this, you are still clear that you should marry, choose a God-fearing person of a temperament compatible with your own lest you “have a domestic war instead of love,” advises Baxter. Look for “a competency of wit; for no one can live lovingly and comfortably with a fool,” and also for “a power to be silent, as well as to speak; for a babbling tongue is a continual vexation.”21 Richard’s feet were always on the ground, and the wisdom of what he says here is obvious.

The mutual duties of husband and wife are listed as love; cohabitation (“a sober and modest conjunction for procreation: avoiding lasciviousness, unseasonableness, and whatever tendeth to corrupt the mind, and make it vain and filthy, and hinder it from holy employment”22); fidelity; delight in each other; the practice of quietness and peace (“Agree together beforehand, that when one is in the diseased, angry fit, the other shall silently and gently bear, till it be past and you are come to yourselves again. Be not angry both at once”23 ); spiritual support; care for each other’s health and good name; and help in all relevant forms.24 Elsewhere Richard boils the matter down with beautiful simplicity in question and answer, as follows:

I pray you, next tell me my duty to my wife and hers to me.

The common duty of husband and wife is,

1. Entirely to love each other . . . and avoid all things that tend to quench their love.

2. To dwell together, and enjoy each other, and faithfully join as helpers in the education of their children, the government of the family, and the management of their worldly business.

3. Especially to be helpers of each other’s salvation: to stir up each other to faith, love, and obedience, and good works: to warn and help each other against sin, and all temptations; to join in God’s worship in the family, and in private: to prepare each other for the approach of death, and comfort each other in the hopes of life eternal.

4. To avoid all dissensions, and to bear with those infirmities in each other which you cannot cure: to assuage, and not provoke, unruly passions; and, in lawful things, to please each other.

5. To keep conjugal chastity and fidelity, and to avoid all unseemly and immodest carriage [conduct] with another, which may stir up jealousy; and yet to avoid all jealousy which is unjust.

6. To help one another to bear their burdens (and not by impatience to make them greater). In poverty, crosses, sickness, dangers, to comfort and support each other. And to be delightful companions in holy love, and heavenly hopes and duties, when all other outward comforts fail.25

Such was the vision for marriage with which Richard and Margaret were armed when they covenanted together to be man and wife. As with so much else in historic Puritanism, one cannot but be struck by the mature, thoughtful, farseeing, fact-facing realism of the whole approach, and recognize the contrast with the starry-eyed, shortsighted, self-absorbed goofiness—there really is no other word for it—that marks so many dating and mating couples today. If all spouse-hunting young people were counseled in Baxterian terms regarding marriage, some marriages would never happen, and much of the misery of present-day marriage breakdown would be avoided.

Richard and Margaret themselves, as we shall see, were what we would call “difficult” people, individual to the point of stubbornness, temperamentally at opposite extremes, and with a twenty-year age gap between them. Moreover, they were both frequently ill and were living through a nightmarishly difficult time for persons of their convictions. For Richard, who was officially regarded as the leader and pacesetter of the Nonconformists, legal harassment, spying, and personal sniping were constant, making it an invidious thing to be his wife. Yet cheerful patience, fostered by constant mutual encouragement drawn from the Word of God, sustained them throughout, and their relationship prospered and blossomed. They demonstrated not only the grace of God but also the realistic wisdom of the down-to-earth ideal of marriage by which they lived.

To be sure, the Puritans knew all about falling in love. “Marriage love is often a secret work of God,” wrote Daniel Rogers, “pitching the heart of one party upon another for no known cause; and therefore when this strong lodestone attracts each to the other, no further questions need to be made but such a man and such a woman’s match were made in heaven, and God has brought them together.”26 But the Puritan emphasis was that, whether or not this delirious “pitching of the heart” is an element in the married couple’s present experience, sustained practical friendship and mutual help is in every case a matter of divine command.

So Puritan teachers often said that in choosing a spouse, one should look, not necessarily for one whom one does love, here and now, in the heart-pitched sense (such a person, if found, might still not be a suitable candidate for a life partnership), but for one whom one can love with steady affection on a permanent basis. Once more Richard brings all this down to earth, stressing that what makes for God-honoring marriage is not euphoria but character, consideration, and commitment—in other words, personal formation, reflection, and resolution.

If God calls you to a married life, expect . . . trouble . . . and make particular preparation for each temptation, cross and duty which you must expect. Think not that you are entering into a state of mere [pure and unmixed] delight, lest it prove but a fool’s paradise to you. See that you be furnished with marriage strength and patience, for the duties and sufferings of a married state, before you venture on it. Especially, 1. Be well provided against temptations to a worldly mind and life. . . . 2. See that you be well provided with conjugal affections. . . . 3. See that you be well provided with marriage prudence and understanding, that you may be able to instruct and edify your families. . . . [Extended families with servants was the seventeenth-century norm.] 4. See that you be provided with resolvedness and constancy. . . . Levity and mutability are no fit preparative for a state that only death can change. 5. See that you are well provided with a diligence answerable to the greatness of your undertaken duties. . . . 6. See that you are well provided with marriage patience; to bear with the infirmities of others, and undergo the daily crosses of your life. . . . To marry without all this preparation, is as foolish as to go to sea without the necessary preparations for your voyage, or to go to war without armour or ammunition, or to go to work without tools or strength, or to go to buy meat in the market when you have no money.27

Marriage preparation today often means no more than suggestions about managing money, handling disagreements, making love, and acting right at the ceremony. Marriage preparation for Richard was a personal spiritual discipline requiring prayerful self-scrutiny in light of all that God wants done and all that may go wrong. The difference is striking and bears a good deal of thinking about. In this, as in other matters, modern Christianity is simply not serious and thorough in the Puritan way.

The understanding of marriage involvement in terms of which Richard and Margaret took their vows is now clear. What is not yet clear is how, relationally speaking, they came to their certainty that marriage was right for them. That is what we must look at next.

Love Story

Three fine Baxter scholars of an earlier day28 found in Richard’s memoir a love story—“exquisite,” “incomparable,” “beautiful,” as they describe it.29