7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

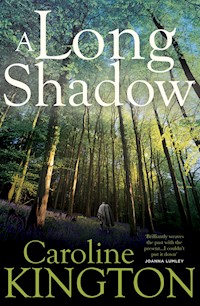

'Brilliantly weaves the past with the present…I couldn't put it down' – Joanna Lumley When farmer Dan Maddicott is found shot dead in one of his fields, he leaves behind a young family and a farm deep in debt. Although the coroner records accidental death, village rumours suggest he has taken his own life so that the insurance payout can save his family from ruin. Dan's wife, Kate, refuses to believe the gossip and is determined to prove to herself, and her children, that his death was an accident. But could it have been murder? Kate discovers a set of old diaries containing secrets that may reveal how Dan really died. Set against the backdrop of the farming crisis of the turn of the 21st century, Caroline Kington's absorbing family drama also tells the secret history of another resident of the farm, decades before, whose tragic tale will come to have major repercussions in the present day.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Published by

Lightning Books Ltd

Imprint of EyeStorm Media

312 Uxbridge Road

Rickmansworth

Hertfordshire

WD3 8YL

www.lightning-books.com

First Edition 2019

Copyright © Caroline Kington

Cover design by Ifan Bates

All rights reserved. Apart from brief extracts for the purpose of review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without permission of the publisher.

Caroline Kington has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as author of this work.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Printed by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

ISBN: 9781785631184

For Miles, whose encouragement and enthusiasm for this novel kept me writing

Contents

1: Susan

2: Kate

3: Dan

4: Susan

5: Kate

6: Dan

7: Susan

8: Kate

9: Dan

10: Susan

11: Kate

12: Dan

13: Susan

14: Kate

15: Dan

16: Susan

17: Dan

18: Frank

19: Dan

20: Kate

21: Frank

22: Dan

23: Kate

24: Frank

25: Dan

26: Kate

27: Frank

28: Dan

29: Kate

30: Rose

31: Dan

32: Kate

33: Frank

34: Dan

35: Kate

36: Rose

37: Dan

38: Kate

39: Frank

40: Dan

41: Kate

42: Rose

43: Kate

44: Frank

45: Dan

46: Frank

47: Kate

48: Kate

49: Frank

50: Kate

Acknowledgements

1 Susan

1943

The light was switched off, the door firmly shut and the tap, tap, tap of Matron’s shoes echoed down the stone corridor. The dormitory was pitch black; not a flicker of light. The blackout curtains blocked the world outside from seeping in, and fear of punishment as effectively extinguished any temptation by the occupants to break the lights-out rule.

The darkness was full of sounds: all little sounds, for the girls knew any disturbance loud enough to attract attention would bring punishment for the whole dormitory; a low mewling from one girl who was terrified of the dark and would whimper like this until exhaustion, or sleep, released her and her neighbours from her terror; muffled sobbing from the bed of another, and then another and another – they had all cried at some point and were likely to do so again. An occasional low whisper made comforting contact in the dark, and all night long the hard iron beds creaked as uncomfortable bodies sought in vain to find oblivion on the unforgiving mattresses.

Susan Norris lay on her narrow bed, her heart thumping so fast she could hardly breathe. She was not a brave girl, but desperation had led her to find a degree of courage and a determination that would have surprised her mother, had she been alive to care. Her body was treacherous with fatigue and she was afraid of falling asleep and, once asleep, not waking till the morning reveille. Inside her coat, she shivered with fear.

It was cold in the dormitory. The blankets on the beds were meagre and many of the girls disobeyed the rules and wore overcoats over the thin, regulation nightdresses. They were not afforded the luxury of dressing gowns but as a consequence of the night raids, their coats were hung next to the lockers in case they had to take refuge in the shelters.

Those lockers contained all the possessions they were allowed to bring to Exmoor House. These were minimal and included a change of clothing for their eventual release, a face flannel, a hairbrush, a purse, which was emptied when they arrived, and a family photograph, although photographs of single men were expressly forbidden.

Susan had already packed her possessions in a small bag and concealed it under her pillow. It was so pitiably little it didn’t make much of a bulge, but Susan had her heart in her mouth when Matron made an inspection of the dormitory before bidding them good night. Susan was also fully dressed, but wrapping her coat tightly around her as she slipped from the lavatory to her bed, nobody had noticed.

As the minutes ticked slowly by and the room grew quieter, she prayed hard there would be no air raid that night. Not that she had any great faith in God. He hadn’t listened to her when, at the age of seven, she had prayed that her mother wouldn’t die, or at the age of nine when she had prayed for her father not to marry the hard-faced woman he had brought in to replace her mother; nor had He heard her when the telegram came reporting her father missing in action; nor when Franklin’s regiment left overnight; nor when her period hadn’t come. If there were an air raid, it would be difficult for her to slip away as she intended. The girls would be counted in and counted out of the shelter and if she was not there, the hunt would begin immediately and she would be brought back and punished.

Exmoor House was originally a workhouse. Part of the old stone building was used to provide shelter for the elderly too poor or infirm to take care of themselves. Faced with increasing numbers of young, unmarried, pregnant girls, particularly since the stationing of US troops in the West Country, another wing had been opened and girls were referred there from all over the region.

As if to punish them for their transgression, life in the mother and baby hostel was one long ordeal. Kept there for the six weeks up to the birth of their children, the girls worked long, hard days, scrubbing floors and staircases, washing, ironing and cooking for themselves and for the old folk. There were few enough privileges, and these were removed at the slightest sign of insolence or misbehaviour. A pitiful wage was paid for the work they did but this was kept by the moral welfare worker responsible for them until their release, unless, of course, they lost it in fines in the interim.

After childbirth, their tasks become less onerous, being more related to the care and cleanliness of the nursery than the old folks. At six weeks, having loved, cared, and nurtured their little ones through the most vulnerable period of their lives, the girls were expected to hand the babies over for adoption.

It was this prospect that had driven Susan to plan her escape. She knew she would be too weak to resist the authorities who asserted it was ‘in her and her baby’s best interest’. But she knew that if she did give them her baby, it would be the worst thing she could possibly do. As she scrubbed the stone staircase outside the reception room where the babies were handed over, the bitter, desperate wailing of a young mother had struck a corresponding chord in her heart. She had not lost faith in God sufficiently to believe Franklin would not get her letter and come to her aid. What would be his reaction if he discovered she had given their precious baby away?

So she lay in her bed, shivering with cold and fright, heart thumping, baby kicking, listening to the clock on the wall of the old workhouse marking time. The hour when the raids normally seemed to start came and went. She should make her move: if she delayed, she would not be far enough away by the time her absence was discovered.

Quietly she slipped out of her bed, felt for her bundle and balancing it on her distended body, wrapped her coat tightly around her. Holding her shoes in her other hand she tiptoed, in her bare feet, to the door. It was not locked, as the girls, thus far gone in their pregnancy, needed to make frequent visits to the lavatory, and although one member of the Board of Governors had suggested that the door be secured and the girls use chamber pots, his suggestion had been rejected.

Unchallenged, she crept the length of the long, dimly lit corridor till she reached the night superintendent’s office. Here she paused a moment then crept past. Her knees wobbled so much she could hardly walk, and she dared not breathe; her breathing sounded so harsh and so loud to her she was terrified it would alert the superintendent.

She reached the staircase, clasped the cold stone banister and tiptoed down the stairs. For the first time in her life she had reason to be thankful they were stone: the creaking of wood would have been too much for her overwrought state. Reaching the bottom she whisked round the ornate stone newel post, taking herself out of sight of the main hall, slipping through a swing door to a back passage. Here there was no light to guide her and she had to grope her way along the passageway until she felt the coal-cellar door. It opened and shut behind her with a quiet click that sounded as loud as gun-shot to her.

The blackness and the smell of the coal inside were smothering. There was no guard-rail on these steps and a fall could prove fatal. She could see nothing, eyes open or shut – it made no difference. Sitting on her backside, she slipped on her shoes and bumped herself to the bottom, felt down to her left and found the pair of galoshes she had concealed there days earlier. She put them on, and stumbling and sliding over the piles of coal, she eventually found the packing case that had first given her the idea escape was possible. Clumsily she climbed on top of it, raised her arms and pushed at the coalhole hatch.

The night air rushed in, cold, damp.

With great difficulty she levered her heavy body through the hole and then, panting with the exertion, sat for a moment on the edge and looked around at the world.

It was not welcoming. There was no moon, no stars. The sky was almost as black as the coal cellar, and the air was damp with a light drizzle. But she was, at least for the moment, free.

2 Kate

2001

Everyone had gone, the inquest and verdict having been exhaustively dissected. Kate Maddicott sat alone at her kitchen table, her arms resting on the scrubbed wood, her hands cradling the mug of tea her mother had pressed on her before she had, oh so tactfully, oh so thoughtfully, slipped out to head off the children.

Tactful.

Thoughtful.

Rattling around her brain, faster and faster, like stones in an empty vessel, the words acquired a greater and greater resonance.

Everyone was being so tactful, so thoughtful. Even Ted, even Ted. Direct, plain-speaking Ted… From the very first moment he’d brought her the news, he…everyone…groped for the right words. Antiseptic, soothing: the right words. Words that wouldn’t cause too much collateral damage, but words that hurt, hurt so badly, hurt without ending – impossible they could be otherwise. The right thing to say… Nothing was right. Tactful, thoughtful – at best, at best, oh…just so inadequate…

A tune came floating from nowhere – ‘So ta-ctful, so thought-ful dum dum… So ta-a-actful are they-ey to–oo-oo me-ee.’

She stopped abruptly. What was she doing? What was she thinking? What was she feeling?

‘Nothing! ‘She shouted aloud to the empty kitchen. ‘I’m feeling…nothing. Dan’s dead and I’m feeling nothing. Nothing! I’ve no feeling left. I’m dead, too.’

The electric clock ticked on quietly, unhurriedly; the Aga pop-popped and gurgled deep in its belly, as it always did; and the walls, that long ago she and Dan had painted a soft yellow, glowed like a slice of lemon meringue pie in the late afternoon sun. Quietly, inexorably, the warm, welcoming kitchen had an effect on her. It impinged on the numbness that had gripped her; filled the empty vessels of her body and her mind with what felt like cold, grey clay, banishing all feeling.

She put her head on her arms and wept.

At first the grieving was a gut-wrenching animal sorrow, without shape or thought, but as she continued to weep, like fingers tracing over fresh wounds, she relived the agonies of the last few weeks. Images, graphic and painful in their detail, painted her darkness.

Ted’s face, agonised, his mouth forming and re-forming, trying to frame words that didn’t want to be articulated... ‘Girlie, I don’t know how to tell you this…it’s Dan. He’s dead. It was an accident. It must have been…’

What had she said? She couldn’t remember what she’d said. She had walked across the farmyard to greet Ted with some trivial quip about a date he’d had the night before. It was a beautiful morning and the seductive murmurings of the collar doves filled the air. At the sight of his face, everything froze. Sound stopped, senses stopped, the colour of the world bleached away.

‘It was an accident, it must have been.’ Dr Johnson, a little while later as he sat with her at the kitchen table, his fingers nervelessly pulling at the cap of his pen, trying to keep his distress under wraps. He had been present at Dan’s birth and then helped Kate give birth to Ben and to Rosie.

‘It was an accident. Daddy’s had a terrible accident.’ She couldn’t stop the awful hurt. She couldn’t kiss this pain away. At eight and six they were old enough to sense the enormity of their loss but not know how to deal with it. In Kate’s dreams, Ben’s stricken look jostled alongside Dan’s mutilated and bloodied face.

They hadn’t let her see the body. She had rushed with Ted to the edge of Sparrow Woods where they had found him, but an ambulance and a police car were already there and at the insistence of someone, she couldn’t remember who any more, she was led away and Ted went with Dan, to formally identify him, they said.

How had it happened? How? Why?

‘Why?’ Always she came back to the same point. If it was an accident, how did it happen? And if it wasn’t, why should Dan do such a thing? Why?

She was aware, after the first outpouring of sympathy, that there was doubt in many people’s minds. Great Missenwall, their village, was a small community, and along with the shock and the sympathy had come the gossip and the speculation. In open discussion the emphasis was on the word ‘accident’. But Kate knew what was left unsaid – farmers aren’t in the habit of climbing stiles with cocked twelve bores, and then to trip… But the only other explanation was unthinkable.

‘Believe me, Kate, Dan would never take his own life. Never. He loved you. And he’d never, ever, do such a thing to the children. He loved them too much. Suicide is selfish. Dan wasn’t selfish. Whatever his faults, he wasn’t selfish. You know that. You must know that!’ Polly, Dan’s mother, her eyes red and swollen, her face drawn, had turned fragile overnight.

Kate knew Polly was right. The Dan she knew would never inflict such pain. Never torture them in such a way. He loved them. Of course he did. And he knew how much they loved him. He did, didn’t he?

But then she’d discovered that Watersmeet farm was struggling; that it had been for some time. She’d been aware things were getting difficult, but never…never had she imagined that Dan would have kept the extent of his debts from her.

He’d not told her.

Before the children were born, they’d shared everything. More recently he had become moody and distant, not inclined to talk about the farm. She, preoccupied with the children, had let that side of their relationship drift. Had she let it drift so much Dan had felt he could no longer confide in her? That he couldn’t tell her just how bad things had become?

‘You were not aware then that Dan had reached the limit of his overdraft? That he was looking for ways to offset his debts?’ Mr Morgan, at the bank, was too polite to show surprise, but he was surprised nevertheless.

She had no tears left. Her eyes felt scratched and sore. She stared, without seeing, at her untouched mug of tea while her brain, refusing to rest, searched for answers, for explanations as it had done, unceasingly, since she woke from Dr Johnson’s drug-induced sleep to face the consequences of the nightmare into which Dan, by the manner of his death, had plunged her.

At first she had functioned in a trance and then she had raged. Raged against the horror of it all, the unfairness of it all; and then raged against Dan for inflicting such pain on her, on his children, on them all. Then she put herself in the dock and crippled with guilt and self-loathing for having failed Dan, she floundered in unimagined depths of misery. Failed him because he hadn’t told her he had gone beyond the limits of his overdraft, that he was under instructions from the bank to offset his debts…

And because he hadn’t told her about the life insurance.

Far from being a comfort, that had been a terrible shock, the most unwelcome piece of news she could possibly have received. After her interview with Mr Morgan, she’d assumed she would have to sell the farm. Then she discovered that shortly before his death he’d taken out a life insurance.

What was she to think? The inference was unavoidable. What had Dan been thinking of? Had he planned all this? Why hadn’t he told her? How had she become so disconnected? Had he tried to talk to her and she’d not listened, or simply not understood what he was telling her?

The inescapable fact was the insurance would not only clear their debts, but leave Kate with some capital. So what conclusions were there left to draw?

No, she absolutely refused to believe it.

In the private opinion of everyone but those who knew him best, the news of the farm debt and of the life insurance settled the question.

The coroner was convinced otherwise and a verdict of accidental death was recorded.

Kate pushed the tea away and putting her head on her arms, closed her eyes. If only she could go to sleep and not wake up… No, that wasn’t the answer. If only she could wake up and see Dan sitting there, on the opposite side of the table, smiling at her, teasing, because she’d nodded off. If only…

The futility of ‘if only’.

She sat up and opened her eyes.

He wasn’t there.

Of course not.

The following morning, as the day was breaking, Kate climbed the hill that led out of the valley. At the brow, she stopped and turned to look back down on Watersmeet. She breathed in deeply, feeling as she did so that it was the first conscious breath she had taken for ages. The air was fresh and sweet, untainted by the accumulated smells of the day. The sun, low and young, rose behind her to light the honey-coloured stone of the house and turn the reddening leaves of the Virginia creeper ever more scarlet.

She loved this view of the house. She had fallen in love with it the first time Dan brought her here at much the same time of year, eleven years ago. The façade of the house was early Georgian, ‘with plenty of alterations from less gentrified Maddicotts round the back.’ Dan had grinned, obviously pleased by her reaction.

It was not a large or particularly grand house but it was elegant, warm and inviting. It sat in the bottom of a narrow valley, bordered on one side by a modest river and by a brook in the front that danced its way in the early sunlight down to the river. A yew hedge separated the riverbank from the garden and a crumbling stone wall, sprouting daisies, valerian and ivy-leaved toadflax, stood between the brook and the front garden. A flat stone bridged the stream to provide access to a pair of old iron gates, and the flagstone path to the front door of the house was bordered with thick bushes of lavender.

To the left was the farm itself – a motley collection of stone buildings grouped around the yard, including barns, and a milking shed. Beyond the house and farm wound the river valley, and the rolling meadows where Dan’s sheep and cows grazed…

‘They’ve been doing that for hundreds of years, you know,’ Dan had said. ‘It’s good pasture and the milk is rich and creamy. You can try some, later.’ He had stood with his arm firmly round her shoulders. The first weekend she came down to Watersmeet, they’d scarcely let go of each other. ‘Look over there, the grey roof – that’s the cheese shed; Mum runs the cheese-making operation from there.’ Dan had paused. ‘My dad’s death was sudden. It hit her very hard. Setting up the business sort of helped her cope, I suppose…’

It was easier for Polly, thought Kate. She’d had Dan to take over, Dan to see her through the dark times. But now Dan had gone and left Kate; left her alone with two small children and a farm to run. And this huge question mark. Dan’s father died of a heart attack. No doubts attached to that…

‘You can’t see from here Kate, but beyond that valley we’ve the crop fields and more pasture, and another dairy unit. Believe it or not, we once had five tenant farms. But now, with one exception, they’ve all gone. It’s a shame, but that’s the way it is. Bigger fields, bigger yields, and it’s still a struggle…’

But if life was a struggle for Dan, it didn’t show that day. She closed her eyes and pictured him, young and tall, with white even teeth and strong features, his hair the colour of dark honey. His skin was clear and light gold and his eyes…his eyes were a melting brown, and so serious.

When he looked at his farm, as he had done the day he introduced her to it, he had become completely absorbed. It meant everything to him. She had realised that then, and had been entranced by it. And with a prescience, which quite unnerved her at the time, for she had never encountered anyone quite so wedded to a place, she knew if their relationship was going to go anywhere, it would be she who would have to make sacrifices.

Sacrifices.

She screwed her eyes tight shut, the longer to hold onto his image. But the image dissolved, grief took over, and alone on the hillside, looking down at Watersmeet, the home and lifeblood of generations of Maddicotts, she wept.

3 Dan

1990

At the end of a slow-moving queue, Dan Maddicott, his stomach grumbling plaintively, shuffled towards the tables laden with goodies. With one hand he gripped a glass of champagne precariously moored on the edge of a plastic plate, and with the other he helped himself to food. Cold meats, cold salmon, cold turkey, savoury rice, potato salad, green salad, tomato salad, creamy, glistening coleslaw… The wedding feast held no surprises, but he was hungry and before long a laden plate counter-balanced the anchorage of the full glass.

The noise in the marquee was deafening. Released from the sombre surroundings of the church, where the muted coughing, the whispering, and the tentative singing had reflected the awe and unease of a congregation on their best behaviour, the wedding guests chatted, laughed and shouted without inhibition.

It had been a typical June day: the early sunshine had given way to a succession of sharp showers so there was no prospect of going to sit on the grass outside. He looked around the marquee for somewhere to sit, but as he’d been slow joining the queue for food, most of the tables were occupied.

Clutching his plate and glass and weaving a precarious path through the tables, Dan flashed a smile at his mother, already seated and absorbed in conversation with one of her numerous sisters, avoided the eye of his Auntie Marilyn, who had an empty place beside her, and was rescued by a shout.

‘Dan! Dan! Over here!’

Max, his cousin, was at a table with a group of people, about his age, in their early twenties he guessed, none of whom he recognised. He headed towards them.

‘Coo-ee, Danny!’ His Auntie Marilyn had spotted him.

He smiled at her and with an apologetic shrug, indicated with his full hand, the table waiting to make room for him. The casual gesture had disastrous consequences. The champagne glass slid out of its mooring and emptied into the lap of a blue silk dress worn by a bridesmaid sitting at the table. Amid her shrieks of outrage and the shouts of laughter, Dan failed to correct the sudden imbalance of his plate following the abrupt departure of the glass; in a trice it tilted and what had been his breakfast, lunch and supper splattered across the floor of the marquee.

Mortified, cursing under his breath, he grabbed a napkin and attempted to mop the champagne-saturated dress.

Max jumped to his feet, shouting with glee. ‘Meet my cousin Dan Maddicott, everyone. He’s a farmer, yer know, oop from Zomerzet. They farmers got a way wiv birds – they like to throw food at ’em!’

Dan was saved the bother of a suitable retort by a call to attention from the top table. His glass was rescued and re-filled from a stack of bottles under the table and he sank into an empty chair next to his victim, whispering his embarrassed apologies. She had, he noticed for the first time, soft dark hair and round, twinkling eyes, the colour of forget-me-nots.

An only child himself, Dan had hordes of cousins, many of whom had spent part of their holidays ‘keeping him company’ as his mother put it, on the family farm in the soft, rolling, green hills of the West Country. His father had also been an only child. His mother, however, was one of seven, and the cousins kept on coming.

It was a cousin, Max’s younger sister Mary, who was getting married on this day. Their father worked in the diplomatic service, so the brother and sister had been frequent visitors to the farm. From their early years they had hunted hens, dammed streams, leaped among the hay bales in the barn, spied on the farmhands, and with their hearts in their mouths, sneaked into the yard of Woodside Farm to look with fascination at old Jem Leach’s collection of caged birds.

The Leaches had been tenants of the Maddicotts for as long as the Maddicotts had owned Watersmeet. There was little love lost between them. If the children were caught, they could expect a vicious clip round the ear followed by an angry telephone call and a ticking-off from whichever exasperated parent had been forced to collect them.

The last excursion they had ever made to Woodside was vividly imprinted on Dan’s memory. As he watched the little bride smiling up at her new husband, Dan’s thoughts wandered back to that time when he, Max and Mary – she was about ten – had slipped into the empty yard of Woodside and crept into the gloom of the big barn where old Jem kept the large cage…

A barn owl, a buzzard, two kestrels and a falcon, all fastened by short trusses to individual perches, stared at them with angry eyes.

‘They shouldn’t be in here,’ Mary whispered. ‘It’s cruel. I can’t bear it. We must do something!’

Max was all for instant action. ‘Let’s set them free. He’s a bastard, keeping birds shut up like this. Dan, your clasp should break this lock… Now…while the coast’s clear. Imagine old Jem’s face when he discovers his birds have flown!’

Dan hesitated. As he did so there was a roar of anger from the barn door.

‘What yer think yer doin? Getaway from they birds. Little varmin. Jest wait till Oi gets thee…’ And he rushed forward. They were too quick for him.

Scattering to the left and right of the old man, they made for the door and the freedom of the yard. Out in the sunlight they pelted across its uneven, dried-mud surface, to the open gate and the safety of the woods beyond. Dan made the trees first, Max hard on his heels.

There was a cry and spinning round, Dan saw Mary stumble and trip. She had barely got to her feet when Jem, with a shout of triumph, grabbed hold of her. Max pulled Dan down into the undergrowth and, dismayed, they watched Jem march a weeping Mary across the yard back into the barn.

Moments later he appeared without her and, with a triumphant lift of his head in the direction of the woods, shouted ‘Oi’ve got thee now my little varmin. Oi’ve got yer sister under lock and key. Give thyselves up and Oi’ll let her go. No show an’ her stays there. All noight if necessary. Geddit?’

The boys got it all right.

Max was furious with Mary and was all for leaving her to her fate. ‘He won’t keep her there all night. He wouldn’t dare. Bloody girl – typical! Fancy tripping like that. We should never have brought her. It’s her own fault. Bloody, bloody girl.’

They looked on as Jem pulled up a small bale, sat down and lit a pipe. A high, thin wail came from the barn then cut off abruptly.

The sound of that wail unnerved Dan. ‘We can’t leave her there, Max,’ he hissed. ‘You were gonna rescue those birds. We can’t just leave her locked up. We’ve got to get her out.’

It was a challenge and at the prospect of a rescue attempt, Max was immediately fired. They lay in the undergrowth arguing over first one plan, then another. And the foul old man sat there, smoking his pipe, casting looks in their direction and cackling.

‘If only we could distract his attention,’ said Dan, staring across at Jem. ‘Then get into that barn, without him seeing us. He’s probably pushed her into the old tool cupboard he keeps in the far corner. I’m sure my knife is strong enough to break the lock.’

‘Unless he’s put her in the birdcage,’ said Max with ghoulish relish.

Dan shuddered. ‘Christ, Max! We’ve got to get a move on. Look – you stay here. I’ll creep round to the back of the yard and make it to the barn without old Jem spotting me. Watch me carefully. When I signal to you, you must stand up and shout, yell, distract his attention any way you can so I can slip inside the barn without him noticing.’

Not ready to relinquish his role as the leader, Max scowled. ‘No, you stay here. She’s my sister. I’ll be the one to do the rescuing. Give me your knife.’

Furious, Dan turned on Max. ‘Don’t be so pathetic. I can run faster than you, and I know the layout of the yard and barn better.’

Max never backed down lightly and certainly not to Dan, his junior cousin, but faced with this rare explosion of anger, he immediately conceded. ‘OK, OK. But no mistakes. We don’t want you locked up an’ all…’

A call for quiet from the top table brought Dan back to the present. He craned his head to get a better view of the bridegroom.

As a teenager, if he thought about it all, he’d imagined that one day maybe he would marry Mary. But after the events at Woodside that day, the three of them had drifted apart. Then Dan’s father had died prematurely; Dan went to an agricultural college and took over the farm, and in London, Mary and Max had become absorbed in their own circles of friends. Max had moved easily from university into the financial market and was, the aunts whispered, ‘making more money than was good for him’. Mary had gone on to get a degree in business studies and found a job she loved with a PR firm.

And so now here she was marrying someone else.

Shortly after she’d announced her engagement, Mary had brought him down on a brief visit to Watersmeet. Clive was a wine taster for some prestigious company, and exuded ambition.

‘Clive’! I ask you…what sort of name is Clive?’ Dan had snorted after they’d left.

‘You’re just jealous,’ laughed his mother. ‘I thought he was very agreeable and Mary is clearly very happy.’

And indeed she was. The trouble was Dan could not find Clive ‘agreeable’ in the way his mother did. In Dan’s opinion, he was just a little too smooth and a little too self-confident, and Dan did not like him. But he was on his own.

Clive stood up to make a speech. He was a good-looking fellow, Dan had to admit, the cut of his morning suit emphasising an athletic physique, not tall (but then Mary was petite), with a thick head of dark hair swept back from a high forehead. He was smiling down at Mary and taking her hand, he addressed the guests.

Dan helped himself to some more champagne. It was hot in the marquee. The champagne was going to his head. He was hungry. He shifted in his chair and glanced surreptitiously under the table to see if he could retrieve any of his lost food. Two feet, his own, sat squarely in a mushy pile. He groaned.

‘What’s wrong?’ The girl with forget-me-not eyes whispered. ‘Are you unwell?’

‘No, just hungry.’ Dan whispered back. ‘I haven’t eaten anything today and I’ve been up since five. If I don’t have something soon, I shall pass out when we stand to toast the happy couple.’

The girl smiled. A smile that lit up her face, her eyes, her mouth, every muscle; a smile like the early morning sun, slowly, steadily, rising, illuminating everything with liquid gold. Dan had never seen such a smile.

He melted.

By the evening, the formality of the wedding had given way to the obligatory drinking and dancing bash. Dan stuck with Max’s group, hoping to spend as much time as he could with the girl he’d drenched in champagne. Her name, he learned, was Kate Dinsdale; her mother called her Katherine; her friends called her Katie; she preferred to be called Kate. She told him she was an old school friend of Mary’s and she had known both Mary and Max since she was thirteen.

‘So, you’re Dan,’ she smiled. ‘I meet you at long last. Mary used to boast about you and Watersmeet…’

Dan found Kate entrancing. Tall and slender, her face illuminated when she talked, and her eyes – he’d never seen eyes so blue – were bright and intelligent. Under her questioning, he told her a little about Watersmeet and his life there and she, in turn, told him about herself.

She worked in television as a researcher, with aspirations to be a documentary producer. At that moment she was working on a series of ‘Writers and Their Writings’ and was terribly excited about a planned interview with some novelist or other. She was about to regale the bemused and bewitched Dan with the plot when they were interrupted.

Max, as Dan would have expected, was the epicentre of his coterie of friends and had flitted around the reception flirting with every eligible girl. His attentions were now on Kate.

‘Darling,’ his arm slipped round her waist. ‘Dan’s hogged you long enough. It’s my turn. Come on, I want to dance.’

Kate playfully attempted to disengage herself. ‘Later, Max, I’m talking to Dan about Puffball. It’s set near where he lives, and I want to find out how...’

‘The only puffball Dan knows about is the sort you eat! Contemporary female writers are not his forte. But I tell you what, if you want to find out what it’s like living in the depths of nowhere, we’ll go and visit Dan one weekend. Bring a little excitement into his dull old life, down on t’ farm! But now, sweetheart, it’s time to boogie.’ And he steered her purposefully away.

Dan stared after them, feeling irrationally disappointed. He found Mary by his side. ‘I didn’t realise Kate was Max’s girlfriend?’ It was more of a groan than he’d intended.

Mary laughed. ‘She probably doesn’t see it that way. Max is determined they should be, and what Max wants, Max normally gets. But she’s holding out. Brave girl. He’s not used to being resistable.’ She looked at Dan. ‘Don’t tell me you’re smitten too? I thought you were devoted to me, only me, my darling Dan?’

‘And so I am,’ he looked down at his little cousin. Her heart-shaped face was flushed and her grey eyes were bright with excitement and laughter. ‘Completely devoted,’ he lifted her hand and kissed it with mock formality. ‘But you have married another, and unless I am to spend the rest of my natural as a bitter and twisted bachelor…’

She laughed. ‘Impossible. But I don’t suppose there are too many matrimonial prospects in Great Missenwall. You’d better get in there, Dan. Don’t worry about Max’s feelings. After all, he’d have no hesitation in walking all over yours...’

By the end of the evening, emboldened by Mary’s words, he had exchanged telephone numbers with Kate and elicited a promise that she would have dinner with him next time he was in the city.

But that was the sticking point. She lived in London; he lived in the heart of rural England. He was a farmer, a twenty-four-hour occupation; she was a television researcher with as little time to spare, it seemed, as he. A casual acquaintance was never going to be on the cards.

4 Susan

1943

At dawn, a grey, reluctant affair unremarked even by the birds, the drizzle had given way to rain. The road was a filthy combination of mulched leaves and mud. A slight wind drove the rain into Susan’s face. Every now and then, overhanging branches of trees that might have offered her some protection against the weather deposited large drops of water on her head. These trickled straight down her neck and back, soaking her inside as well as out. Her thin coat was no protection against either wind or rain. Worse, the sodden, freezing fabric added to her discomfiture and, flapping sullenly around her body, slowed her progress. Rivulets of water ran down her coal-grimed legs and into her galoshes. The fine fair hair Franklin had loved to twist in his fingers now hung in darkened, dripping tails, plastering her small pale face.

She passed a herd of cows squelching in the mud around their feeder. They lowed a mournful protest at the sight of her. They should have been snug in their winter quarters, not out in the mud and wind like her. Their barn had been blown to smithereens by a stray bomb, dropped after a night raid on Bristol. But they, at least, had someone to care about their plight and they had been given plenty of hay to eat.

As she passed the entrance of a farmyard a dog rushed out, barking ferociously. His unexpected and aggressive appearance badly shook her. She hurried on, trembling with fright in case he followed. Having seen her off, however, he lost all interest, and she trudged on, her trembling slowly subsiding.

The occasional rook eyed her askance through the rain.

Otherwise, there was nothing and nobody about.

Faint and hungry as she was, she was relieved. She knew her appearance would attract attention and she wanted to get as far away from Exmoor House as she could before she encountered anyone.

When she had first started to plan her escape, she had asked one of the girls in which direction Bristol lay, and so it was in that direction, without gaslight or starlight to guide her, she had started out.

In the blackness of the night it had been impossible to check her direction by any signpost, but at dawn she chanced on a milestone and was both encouraged and dismayed by the information that she had walked eight miles but that Bristol was still some thirty-five miles away. She was on the right road, but oh, how her feet ached, her body ached, her baby kicked, and how sick she felt.

There was an animal trough beside the stone milestone, fed by a bubbling spring. In the stone basin she washed her face and hands clean of coal dust, drying herself on the hem of her smock; then she drank the icy water. A hedge bordered a small orchard and she was able to reach the odd apple withering on the boughs. Thus fortified, she again set off.

She had decided, once she got to Bristol, she would try to find her Auntie May, her mother’s sister. When her dad had re-married, her stepmother had quarrelled with her auntie and the family broke off all contact. Her dad removed his family to Shepton Mallet and the rest of her relatives had remained in the city. Susan could not remember much of Auntie May, but she did have vague memories of a plump, smiling face and of being fed warm, crumbly, ginger biscuits. On such sketchy evidence she had convinced herself she would not be turned away.

Progress was slow. As the day lengthened, the traffic on the road increased. Not a great deal, and mainly local delivery vans, tractors, carts and an occasional car, but Susan was all quivering antennae and at the first sound of a vehicle she would conceal herself in the nearest field or ditch until the danger had passed. Nobody spotted her, or if they did, they paid her no attention. It was a cold, wet day and people were more concerned in sorting their business and getting back to the comfort of their homes.

By early afternoon she was exhausted and thoroughly dispirited. For the umpteenth time she had dragged herself out of a ditch where she had taken quick refuge at the unheralded appearance of a tractor. Nettles had viciously stung her legs and a stray briar had lashed out, drawing a thin scarlet line across her cheek.

For the first time since she had set out, she gave way to loud unchecked sobs. So wrapped up was she in her misery, she didn’t notice a ramshackle van coming round the bend behind her.

5 Kate

2001

As the number of days after the inquest lengthened, the pressure on Kate to make a decision about the farm’s future grew.

The family and the community had rallied round, and the funeral, so dreaded by her, actually helped them all.

Her mother returned home. Before she left, she tried hard to make Kate go with her, but Kate resisted. She knew that both Ben and Rosie couldn’t really believe their father was dead. And in her heart, too, there was denial, a refusal to believe she’d never see him again. Those feelings were made worse by thinking she’d seen him – in the street, in a shop, in a passing car. Each false sighting left her bruised and bleeding afresh.

In the meantime the whole legal business of the estate was being processed; the farm was ticking over, and she knew they were all waiting for her to tell them what should happen next. It was Polly, her much-loved mother-in-law, who finally stirred her to action.

‘I know, Kate, that you still haven’t made up your mind about…well, about your plans yet,’ she began. ‘But I think it only fair to tell you, I’ve decided to give up cheese-making.’

Polly Maddicott had always seemed ageless to Kate. She was neat and elegant, her skin smooth, her eyes clear and her cropped hair shiny. But today, Kate noticed as Polly sat, nursing a mug of tea in an old Windsor chair, a ray of sunlight falling across her face highlighted lines that had not been there before and silver hairs glinted among the auburn.

‘I suspect,’ Polly continued, betraying no emotion, ‘in the end you’ll feel the wisest course is to sell the farm. Your mother said you’ve more or less decided to…’

Kate was irritated. ‘Mum’s leaping to conclusions, Polly. You know what she’s like… I haven’t decided anything yet. Besides you know I’ll tell you first.’

‘That’s as maybe. But I’ve been thinking a great deal about my future as well as yours. I really don’t want to pressurise you, you’ve got enough to contend with as it is, but…well, if you sell, I think I’d like to move.’

‘Away from here?’ Kate was startled. Polly was so much part of Watersmeet it seemed inconceivable she should even think of leaving. ‘Away from Watersmeet? But you’ve spent most of your life here. You’ve so many friends here. Where would you go?’

‘Oh, I don’t suppose I’d go very far. But Kate, my cottage is so close, every time I open a window or step out of my door, I look down on Watersmeet. If you were to sell... No, of course I wouldn’t go far away. You’re right, I do have some very good friends here. But also because Ben and Rosie have their roots here and I hope they would come and stay with me, often.’

When Polly had left, Kate cleared the tea things, turning over and over in her mind the seemingly insoluble question: if she sold the farm, where would she go?

Her mother wanted her to move back to Canterbury permanently. Before she left, she had launched into a jumbled outpouring of thoughts and opinions. Her eyes bright with determination, scarcely pausing to draw breath, allowing no interruption, no discussion, no opposition.

‘It would be lovely to have you closer to us, darling. We’ve seen so little of you since you got married. Great Missenwall is so far away and now your father’s getting on, he doesn’t like to drive too far… Not that he’d be able to leave his bookshop for long. You could help him with the books, just like you used to... It doesn’t seem so long ago you and Emily were still living at home, your hair in pigtails…well Emily’s was, you always insisted on having your hair cut. Not that it didn’t suit you…you’ve always had such pretty curls. Doesn’t Rosie take after you? Not quite the same colouring, of course, she must get that from Polly… And Ben is so like poor Dan…’

‘Mum, please…’

‘Darling, they’re growing up so quickly, we’re missing out on their childhoods… And of course, there’s such a wide choice of schools in Canterbury. You’ve so few suitable schools around you and you’ve got to think of these things. After all, if you sold Watersmeet, they could both go to a good prep school and then go to King’s. It’s co-ed now, you know, and still so well thought of... They couldn’t have a better start… Then if you choose to start your career again, we could look after them. You know how much they’ve enjoyed coming to stay… Your father and I have talked it over and we both agree Ben is too young to feel he should follow in Dan’s footsteps. And anyway, farming is so terrible these days. Foot and Mouth, BSE. The poor farmers seem to stagger from one crisis to another…’ She finally ran out of steam and choked. ‘Would you want to burden little Ben with all that?’

No, whatever else, Kate couldn’t face the thought of moving back to Canterbury.

But London was different.

Max had come to stay the previous weekend; a breath of air from another life.

While she was preparing supper, he took the children off for a romp in the garden. Kate could hear them shouting and laughing in a way they’d not done since Dan’s death.

She tried to express her gratitude when he left.

‘Poor little buggers,’ he said, giving her a hug. ‘This valley is still frozen with shock. You can almost touch it. They need to get out and feel something else apart from all this grief. And so do you, Kate. You’re drowning. Why don’t you cut and run? Nothing you can do will bring Dan back. You’re not a farmer; you’ve not a drop of farming blood in your veins. You’re a city girl and in London there are loads of Dan’s aunties and cousins, all of whom would love to make a fuss of you and the children. You need to build a life for yourself, not throw it away, keeping a farm going for Ben or Rosie, which they might not want anyway.’

It was tempting. Life in London seemed so remote it was almost exotic. But if she did go back, she’d have to start a career all over again. The TV industry, her industry, had moved on, as had most of her contacts. There would be a lot of catching up to do.

But she was barely in her mid-thirties. There were years ahead of her. She was a creative, energetic person. Starting afresh would help her…would help her deal with her grief. Working in a different world would mean not being confronted with her loss every day. And Ben and Rosie, surely it would be the same for them? And wouldn’t it be better for them if, away from the shadow of the tragedy that engulfed them, she were to have a more fulfilled life?

Max was right: at heart she was a city person. She’d loved the little flat she’d had in Ealing, with all the buzz and instant accessibility of theatres, exhibitions, concerts. She acknowledged she’d given it all up without a backward glance, but that was because of Dan, and now…

The anonymity of the city was also attractive. The dramatic nature of Dan’s death, it seemed to her, had made her and the children the centre of too much unhealthy attention and speculation. Yes, definitely, a fresh start would be beneficial all round…

‘No,’ said Ben. ‘I don’t want to, ever! London stinks!’

Rosie burst into tears.

The phone rang. It was a local farmer, William Etheridge, a family friend.

Faced with her tear-stained, angry children, Kate hardly listened to him.

‘Hope this is not a bad time to call, Kate, but there is something I’d like to discuss with you. A proposal that you…’

‘Sorry William,’ Kate interrupted, ‘but now is not a good time. I’ve upset the children and I need to…’

‘Good God, Kate, I didn’t mean right now. I am slap-bang in the middle of harvest, but if the weather holds I should finish combining Thursday. Are you free Friday evening, at about 6.30?’

Putting the phone down, Kate turned her attention back to her children. Ben was sat at the table, his arms folded, a look of cold stubbornness so reminiscent of Dan on his face. Rosie had hidden her face in her hands. She crouched down between them and put her arms around them both.

‘I’m just trying to work out what’s best for us,’ she said softly. ‘You’ve always loved your visits to London. We’ve so many friends and family there. If we stayed here, I’d have to decide what to do about the farm. Farms need a farmer and I’m not one.’

‘You could be. You could learn. Ted ’ud help you ’til I was old enough. Rosie and me have already learned loads helpin’ him, so I don’t see why you shouldn’t.’

‘Ben, it’s not that simple…’

‘Yes it is. If you wanted to, you would. You would! You wouldn’t want to leave home. Well I’m not leavin’ here and you can’t make me and nor is Rosie, are you Rosie?’

But the only reply the little girl made was a muffled, ‘I want my daddy.’

Much later, tossing sleeplessly in her bed, she remembered her arrangement with William Etheridge. She puzzled over the call.

The Etheridges had been farming locally since the beginning of the last century. They were very successful and ran a large pedigree beef herd, the envy of the farming community. Muriel, William’s wife, had developed a racehorse stud on the farm and this had considerably added to their wealth. Kate and Dan had been on good terms with them, although William was older than Dan by about seven years so they were not childhood friends. Muriel and Kate had met at a party about a year before she married Dan. The two women couldn’t have been more different but they got along exceedingly well and had become firm friends. Then Muriel had died suddenly of cancer two years ago. After that Kate had hardly seen William.

The last time was at Dan’s funeral.

Sadly she remembered how awfully inadequate she’d felt at Muriel’s funeral. Looking at William’s grim face, the heartfelt sentiments she’d been going to express had felt mawkish, inadequate, and died on her lips. And it had seemed somehow indecent to try and say anything to their two children who, at thirteen and ten, looked so vulnerable and lonely. Very different from the loud, confident children who’d filled the house with their noise.

It must have been the same for people at Dan’s funeral. Afraid to say anything to her in case she burst into tears. Afraid to touch the children in case they broke.

How badly we manage death, she thought.

Finally she fell asleep, wondering whether she should cook supper for William. Whether, indeed, she could be bothered.

The following morning she mentioned the call to Ted.

‘He said he has a proposal to discuss with me, Ted. Have you any idea what that might be?’

Ted, looking even more impassive than usual, was silent for some time before he replied, ‘I’ve not heard anything in particular Kate, but maybe he is going to make you an offer.’

‘An offer? For Watersmeet?

‘I doubt for the whole of the place. He’s a businessman. He’d have no use for all of it. I wouldn’t be surprised if he didn’t make you an offer for a substantial part of the land, and for the herds. I know he’s a beef man, but we’ve a good reputation. He might want to expand into the dairy market – quicker returns than beef. All the beauty of diversification without having to start from scratch.’

Kate stared at him, suddenly feeling very sick. ‘But that would leave just the sheep, and a few fields of cash crops. Watersmeet farm wouldn’t be viable any more.’

‘That’s true, but at least you’d be able to carry on living here, without the worry of the farm.’ Ted’s voice was impassive. ‘You could let out the land he doesn’t want. Keep hold of Woodside Farm, if you want to, and that will supplement your income. In your position it makes sense.’ He looked at her sideways. ‘That is, if you want to stay. This is only speculation, mind; he might come with a completely different proposal. He doesn’t give a lot away, not even to his manager.’

‘Ted…’ It was a question they both knew Kate would ask, would have to ask, both dreading the asking, both dreading the answer. ‘What would you do if I sold the farm?’

Like Polly, Kate thought, as she waited for his reply, Ted had aged. He moved stiffly, without vigour. His black hair was shot with grey. The lines around his mouth and eyes had deepened into gorges and his face was leaner and more cadaverous than ever.

‘Well, that depends, Kate, on who bought it, what their plans for the farm might be, whether they wanted a farm manager, and whether they wanted to work with me and my old-fashioned ways…’

‘Old-fashioned? You? What are you talking about? I’ve never heard such rubbish…’

At her indignant tone, a smile flitted across his face. ‘But times are changing that quickly, Kate. For one thing I never had a college education. All I know I learned here, on the farm. Dan’s father taught me and then I made it my business to carry on learning when young Dan had to take over. My knowledge of modern technology is limited, to say the least, and farming is now dependent on that technology. Mebbe the time has come for me to hang up my overalls.’

‘And Ben said I could learn to be a farmer!’

‘Well, happen he’s right. For farming to be successful these days, you know, it has to be run, well, like any other business.’ Ted sighed. ‘The managing director of a shoe company don’t sit at a bench and stitch the leather; he don’t even design the shoes. No, he employs people who know what they’re doing and he manages ’em. He don’t get his hands dirty.’

‘But Dan was totally hands-on, you know he was. He’d be horrified to hear you talk like this. How can you compare a farm with a shoe shop? And anyway, I know labour costs are a permanent headache. So how can any farm afford to have someone running it who doesn’t get their hands dirty?’

‘Look how much time Dan spent on that computer of yours. Sure he was a hands-on farmer, but if Watersmeet is to survive the twenty-first century it means, for the boss at least, less and less time spent doing the actual farming, and more and more pushing paper.

Kate stared miserably at her boots. ‘Yes, you’re right,’ she said sadly. ‘And it made him very depressed.’

And they relapsed into mournful silence.

But it was very important for Kate to know that whatever she did, Ted would be all right. Dan would expect nothing less.

So she rallied, and gave Ted a direct look. ‘You still haven’t answered my question, Ted. If I sold the farm and you, for whatever reason, couldn’t stay on, what would you do?’

There was only the slightest hesitation. ‘I’d move on, Kate. Change direction. Finish with the land as I finished with the sea before I came here. An old friend of mine’s running a garden centre, up near Lacock. He always said he’d take me on if I was minded to leave the farm. We have to adapt to survive. And I’m a survivor.’

‘A garden centre! But you don’t like flowers. That’s no solution. Oh, why can’t we get rid of Frank Leach, then you could take over Woodside Farm? He’s ruining that place… I hate him being there.’

‘So you might, but Woodside is as much Frank’s as Watersmeet was Dan’s. You know the way it is, Kate, his family have farmed it for as long as there have been Maddicotts at Watersmeet. He’s entitled to be there.

A few days later, William Etheridge, invited by Kate for supper, arrived just as the children were finishing their food. Hearing they were to have a visitor, Ben became prickly and morose and Rosie acquired an unaccustomed shyness. Both children melted, however, when they saw that William had brought with him a bundle of brown and white energy in the form of a Springer spaniel pup.

Muriel had bred Springers and William had held on to her favourite bitch, breeding the occasional litter.

‘I hope you don’t mind,’ he apologised as the two children and the puppy tore outside in a confusion of barks, shrieks and laughter. ‘The little blighter shows no interest in playing with his sisters and follows me everywhere. I thought Ben and Rosie might like to play with him for a bit. Wear him out if they can.’

She smiled at him. ‘It was a good idea. They were feeling particularly gloomy before you arrived.’

‘They’ll be finding it difficult, and making it more difficult for you, I expect.’