Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The Honourable Mrs Victor Bruce: record-breaking racing motorist; speedboat racer; pioneering aviator and businesswoman – remarkable achievements for a woman of the 1920s and '30s. Mildred Bruce enjoyed a privileged background that allowed her to search for thrills beyond the bounds of most female contemporaries. She raced against the greats at Brooklands, drove 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle and won the first ladies' prize at the Monte Carlo Rally. Whilst Amy Johnson was receiving global acclaim for her flight to Australia, Mildred learned to fly, and a mere eight weeks later she embarked on a round-the-world flight, becoming the first person to fly solo from the UK to Japan. Captured by brigands and feted by the Siamese, Japanese and Americans, she survived several crashes with body and spirit intact, and became a glittering aviation celebrity on her return. A thoroughly modern woman, she pushed similar boundaries in her unconventional love life and later became Britain's first female airline entrepreneur. This is the story of a charismatic woman who defied the conventions of her time, and loved living life in the fast lane.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 416

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Victor and Mildred Bruce reunited at Croydon. (Courtesy of Caroline Gough-Cooper)

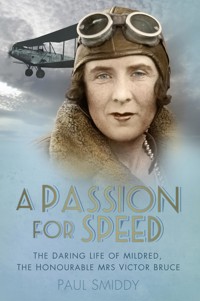

Cover illustrations

Front: Mildred’s Blackburn Bluebird; Mildred with her habitual string of pearls. (BAe Heritage) Back: Painting her steed’s name for the benefit of journalists just before departure on her round-the-world flight. (BAe Heritage)

First published in 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

© Paul Smiddy, 2017

The right of Paul Smiddy to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8530 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword by Polly Vacher

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1

Living the Novel: Rescue from the Brigands

2

Petre and Williams: A Potent Genetic Cocktail

3

Pressures of an Edwardian Girlhood

4

Finding a Lover in Post-War England

5

The Need for Speed: Edwardian Motoring, Brooklands and Meeting Victor

6

Victor: Family and Fame

7

Monte and Marriage

8

No Housewife This: Montlhéry and Breaking Motoring Records

9

Woman on a Mission: Fairy Tale and Fact

10

Departing England: Doing her Bit

11

Plenty of Sweat

12

Onwards to Japan

13

A Stout-Hearted Lady

14

The Last Lap

15

Arrival and Adulation

16

Stars in the Sky

17

Mildred, the Entrepreneur

18

The Restless Soul

19

More Pain for Mildred: An Eventful War

20

Epilogue

Appendix 1: Mildred’s Motor-Racing Career

Appendix 2: The History of the Blackburn Bluebird

Notes and References

Sources

FOREWORD

It is rare to find anyone who embraces all disciplines of speed, let alone a woman! The Hon. Mrs Victor Bruce, who began her addiction to speed before women had the vote in this country, is definitely the exception. This is the story of an incredible woman who lived life on the edge and yet managed to survive into her nineties.

In this biography, Paul Smiddy grips one’s imagination with a roller coaster of accidents, fights with bureaucracy and the sheer guts and courage of an Edwardian woman who defied all the conventions of her time. Paul’s meticulous research and attention to detail brings alive the spirit of a woman who coped with her car landing in a ditch and catching fire, flying over jungles, becoming engulfed in monsoons and landing in a muddy field and turning upside down.

Follow this intrepid lady as she pushes all boundaries in what was then a ‘man’s world’. Undeterred by setbacks, she ventures into the business world and drives herself at a pace which makes one quite breathless. Her focus, endurance, stamina and confidence are carried by her immense ability to charm her way out of any situation.

This is an incredible read as you journey through the life of a truly indomitable spirit.

Polly Vacher (aviatrix)April 2017

A pensive Mildred and Victor before departure. (BAe Heritage)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful I have managed to find many people who share my interest in Mildred and, in some cases, Blackburn Aircraft. My deep thanks go to: Paul Lawson and his colleagues at the BAe Systems Heritage Centre at Brough, for sharing their archive and knowledge so enthusiastically; Alan Wynn and his colleagues at the Brooklands Museum – a time capsule and jewel to be preserved, one hopes, from further industrial and housing encroachment; the staff at The National Archives in Kew – which is quite simply a national treasure; the management and staff at the RAF Museum at Hendon (which also houses some of the Royal Aeronautical Society’s archive material), who are enthusiastic and helpful; Wendy Grimmond, for generously sharing her memories of her father and her father’s collection; Caroline Brown, for showing me her Mildred material (and how to ski); Stuart McCrudden, for his reminiscences; John Davies, for his insight into life at Babdown; Peter Amos, the acknowledged guru of Miles Aircraft; The Orion Publishing Group for material reproduced from Montlhéry, the Story of the Paris Autodrome by William Boddy – I acknowledge that all other attempts at contacting the copyright holder of Montlhéry were unsuccessful; Amy Rigg and her colleagues at The History Press, for their faith, patience and wisdom; and finally my wife Tina for her long-suffering support.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. To rectify any omissions, please contact the author care of the publisher so that we can incorporate such corrections in future reprints or editions.

Paul SmiddyFebruary 2017

INTRODUCTION

This book owes its genesis to my grandmother – a very sweet lady, who was the cousin of Robert and Norman Blackburn, the founders of Blackburn Aircraft (if I ever meet you, I shall share one or two of her stories …). It must have been this that sparked my desire to fly. It certainly sparked my lifelong interest in the Blackburn Aircraft Company, and many years ago I had begun to attend auctions of aeronautica, and had started to purchase the odd artefact connected with Blackburn’s.

I heard of a forthcoming sale of the archive of a lady who had achieved great things in a Blackburn Bluebird – one Hon. Mrs Victor Bruce. The more I delved into her story, the more intriguing it became. Sadly, I was outbid at the auction by a determined (and presumably wealthier!) woman. Some years passed before, one day, I was chatting to a fellow aviator and skier and we established that we were both interested in Mrs Bruce. She, Caroline Gough-Cooper, had been my outbidder, and could not have been more helpful in showing me the archive she had purchased that day. It convinced me that a book just had to be written.

The days chasing Mildred’s story in the archives of Hendon, Kew, Wiltshire and BAe were very absorbing. Separating the fact from the fiction was better than doing any crossword. Some call our heroine ‘Mary Petre’; her husband called her ‘Jane’ – for what reason no one knows, since it was not one of her given names. I have chosen ‘Mildred’, as that seems to have been the most popular in her family. For the world at large, she was known as the Hon. Mrs Victor Bruce: this became her brand, and one that she refused to relinquish, even after divorce. Here is a lady whose story bears telling …

1

LIVING THE NOVEL: RESCUE FROM THE BRIGANDS

Mildred’s dream is not supposed to end like this, but at least she has someone in whom to confide her mounting fear – herself, as she has taken the novel step of installing a primitive dictating machine on the passenger seat to her left in the open-cockpit biplane. The petite 34-year-old Englishwoman is trying to reach her destination at Jask in Persia before the full heat of the day. Even at 5 a.m., four hours earlier, when she had taken off, it had been hot enough, but now she has left behind the comfort of supportive RAF officers at Bushire.

The geography of the littoral below is entrancing, ‘Wonderful, weird rock formations, which extend for miles with precise regularity,’ with ‘some wonderful oxide formations, mountains and hills of varying hues, such as the sugar-loaf formation towering up several hundred feet, of a brilliant turquoise blue.’1 The old river beds appear like silver ribbons leading from her left wing. It is desolate country, devoid of vegetation apart from occasional clumps of palms on the coastline. From time to time, dive boats from the pearl fisheries pass underneath.

She confides to the dictating machine, ‘I am losing a great deal of oil from my engine and am very anxious about it.’ Because of the time pressure and numbed with fatigue, instead of following the coast, Mildred has decided to cut a corner by flying straight across the 100-mile wide Straits of Hormuz. It should save her an hour or so because at 6,000ft in her single-engine, heavily laden Blackburn Bluebird, progress is slow.

A few minutes earlier, she has been cheered by the sight of two warships of the Royal Navy passing through the straits and has swooped low and returned the waves of the ratings on deck. Alan Cobham, on his famous proving flight to Australia in 1926, had been flying a seaplane so he was more attuned to the state of the sea than Mildred. He noted that there were permanent rollers on this part of the Gulf, so a ditching in the sea would make short shrift of Mildred’s Bluebird.2

Her de Havilland Gipsy engine has been proving incontinent since leaving England, and has required the attentions of Imperial Airways engineers several times along the route. A wiser soul would have awaited the arrival of spares at Bushire to replace the offending parts, but her schedule is overbearing, Mildred having been advised that it is imperative to cross the tropics before the onset of the monsoon season. Instead, she has made a temporary repair.

Now that oil is spewing across the windscreen, she is beginning to rue that decision. Her engineering background enables her to discern that it is coming from the thrust race housing – as if that knowledge is a help. A very bad vibration increases her anxiety. It has only been a matter of weeks since she has learned to fly and her experience in the air is negligible – nothing has prepared her for this.

It is late summer in 1930. Amy Johnson has only just returned to Great Britain from her record-breaking flight to Australia, having become the nation’s sweetheart and attracted admirers from around the globe. Mildred has less to prove. She has already won prizes for her motor racing, and broken records on land and sea. More to the point, she is not like Amy – a young, single woman trying to overcome the legacy of spurned love. When she took off from Croydon Airport four days earlier, Mildred left behind a husband and a young son. Nonetheless, her attempt to fly around the world is driven by the same compulsion and confidence that has attended all her previous expeditions.

At the beginning of the 1920s, the British Government had begun to scatter military bases around the Middle East to defend the Empire – but more particularly to protect trading and oil interests. Through the nineteenth century and up to the First World War, the region had seen Britain in direct competition with Germany for trading contracts and influence. Marshal of the Royal Air Force Lord Trenchard had successfully concluded an experiment in Somaliland in 1920 which had proved that RAF bombers were an exceedingly cost-efficient way of containing tribal threats and maintaining British control.

So now, the Gulf States are littered with RAF airfields. Conditions for the airmen tasked with flying the flag are harsh. Women, apart from the wife or daughters of the officer commanding and a handful of nurses, are notable by their absence (the conditions considered deleterious to the health of other females). The heat is exhausting, the postings long. One airman wrote to his wife, ‘Darling; for God’s sake have the bedroom ceiling painted a colour you like, because it’s all you’re going to see for a couple of months when I get back.’3 For the sweating men in shorts at the RAF base of Bushire, a diminutive female in pearls alighting from her Bluebird is a heavenly apparition.

At 11.45 a.m., Mildred speaks to her dictating machine, ‘This may be my end, as the oil pressure is down to nought. See land in distance, but fear engine will fail before I reach it.’ The sea below, she is later to learn, is well stocked with sharks, sting rays and poisonous sea snakes. If she could now only reach the coast, her plan is to land on the beach and top up the engine oil.

By the time the pressure has fallen to 5–10lb per square inch, she has managed to pass the coast. But it is difficult terrain: all the way down from Bandar Abbas (‘Bandar’ being ‘port’ in Persian) there are no major settlements, no harbours, little fresh water and pitfalls of swamps and quicksands.4 A sandstorm provides another distraction, ‘making the surface of the desert look as smooth as a golden billiard table’. Mildred almost pulls off the landing at Kuh Mobarak, a desolate area just inland, some 25 miles short of her destination at Jask. But the Bluebird noses in and ‘amid a deafening sound of splintering wood, and a smell of escaping petrol, I found myself hanging in the straps, the tail of the aircraft bolt upright in the air, and the engine buried in the soft sands’.5 The impact bruises her chin and legs, but she leaps out as fast as she can in her dazed state, aware of the risk of fire. ‘I hit my head but was only stunned for a moment.’6 It is one o’clock in the afternoon, and she needs to shelter from the oppressive heat under the wing.

Some Belushi tribesmen arrive, their children beat her with sticks until they are chastised by the elders and charmed by her. ‘I knew to show fear was fatal so went and shook hands with them and laughed. This changed them and they seemed more friendly.’7 Mildred’s only food is some dates and a small tin of biscuits, her refreshment only half a bottle of water and some Ovaltine. Soon, the tribesmen and children encircle her and try to eat one of her precious Dictaphone records, believing it to be chocolate. They show particular interest in her alarm clock, which she has to set off a few times for their amusement. She gives them some of her ‘treasured’ Ovaltine to drink. Shahmorad bin Salla, the tribal chief, begins to dance, gesturing that she must do the same. She soon exhausts herself and her water, but is resupplied by the tribesman. Bin Salla tells her that if she will sleep under the wing, he himself will mount guard to ensure her safety. Sleep does not come easily.

Feeling a little better the following day, when the tribesmen return she gives one a hastily scribbled message to take to the British outpost in Jask, ‘Please send help. Crashed – Mrs Bruce.’ After dusk, the undaunted Mildred sets to with her machine which, with local help, is soon put back on an even keel. When she examines the Bluebird, she finds that only the propeller is broken, and her spare prop, strapped underneath the fuselage, is quite unharmed. Having lost most of her tools, she has to resort to cleaning the sand-filled engine with her toothbrush. She removes the sharded propeller and fits the spare.

The toil is rewarded and the Gipsy engine bursts into life, but the Bluebird will not pull itself out of the soft ground – she has to confront the fact that she is stranded until outside help arrives. While temporarily alone, she goes down to the shore for a wash and bathe. ‘I heard a splash behind me and turned to find a horrible black native, nearly naked, leaping towards me. He seized me around the waist, and in a frantic struggle we both fell into the water. Somehow I managed to slip from his grasp.’8 She runs back to her aircraft to consult the chapter in her notebook entitled ‘Treatment of Savages’. (Perhaps at the back of Mildred’s mind was Edith Maude Hull’s 1919 novel, The Sheik, in which ‘an English girl was kidnapped in the desert by an Arab Sheik and repeatedly raped, but grew to enjoy it after five pages. “Oh you brute, you brute,” complained the heroine until his knees silenced her’.9)

Before leaving England, Mildred has astutely stimulated press interest by refusing to reveal her intended final destination; journalists therefore have termed it a ‘mystery flight’. At her Esher home, the file of press cuttings is already thick. Her non-arrival at Jask has, of course, been noted, and the following day the British papers pick up on her disappearance. Mildred’s fame has even spread to Australia, where the Melbourne Herald fears she has fallen into the sea between Henjam and the mainland and been lost:

Mrs Victor Bruce [titles apparently carrying little weight in Australia] is a product of her time. A restless, adventurous spirit, with a talent for mechanics, she comes from one of the most distinguished Catholic families in England, and by her marriage is connected with half the aristocracy of England. [They might have added ‘and Wales too’.]

Henjam is the island in the middle of the straits, which she has been observed overflying safely. Victor and her 10-year-old son will no doubt find the morning papers unhelpful to digesting their breakfast back at home in Esher.

Her tribal protectors grow increasingly nervous on the second night, looking towards the mountains to the north, and making gestures towards her throat with knives. Their fears are well-founded. It is all so reminiscent of a 1920s silent film, one almost expects Errol Flynn or Beau Geste to ride over the horizon. Indeed, three brigands arrive on horseback, armed to the teeth, and Mildred’s prose echoes a Mills & Boon novel, ‘The leader was a marvellous sight, and very handsome, with swarthy aquiline features, and straight black hair, worn very long.’ Mildred piles on the charm, and gives the leader £5, but he takes little notice – grabbing her leather helmet, he climbs into the cockpit to begin wiggling the controls. Unsettling enough for a pilot at any time, but for a lone woman, stranded in a very strange country with a fragile and possibly broken aircraft, one can imagine her terror.

But this roving aristocrat has been bred to stare death in the face. James Radclyffe, 3rd Earl of Derwentwater, was Mildred’s five times great-grandfather (and said, by her, to be a cousin of James III). Radclyffe himself had an exotic background: his mother was a daughter of Charles II by his mistress, Moll Davis. Radclyffe was companion to James, the young prince, in his court in exile. Radclyffe returned to England in 1710 and played a central part in the Jacobite uprising of 1715, which ended in defeat at the Battle of Preston. He was dispatched to the Tower of London, and refused to renounce his allegiance to James. George I was deaf to pleas for clemency by various senior courtiers, and Radclyffe was taken to the scaffold on 24 February 1716. In Mildred’s words, ‘It was the custom of the condemned man to tip the gaoler who led him to the block. But this Earl said to the gaoler, “You should be tipping me!”.’ He, and the undoubtedly large audience on Tower Hill, first had to suffer a long and tedious sermon by Samuel Rosewell MA. Radclyffe’s mind had plenty of time to wander into very dark places. According to family legend, when the preacher finally drew breath, Radclyffe examined the block and said to the executioner, ‘That’s too rough for my neck. Get someone to smooth it out.’ After his wish was carried out, he said, ‘Strike when I say “Jesus” three times.’ And so his life ended.

Meanwhile, in the twentieth century, the leader of the brigands rifles through Mildred’s bags and, in what might have been in other circumstances a Pythonesquely amusing move, tries on her evening frock. The ruffians try to force her on to the back of a horse, but the leader of the Belushis stands his ground and remains at her side. Before riding off in disgust, they take her Burberry coat as a final souvenir. The following day, she sets off on foot for Jask, with her guardian angel – the Belushi Chief, bin Salla. Sensibly, she has written on the Bluebird’s wing a succinct message for any would-be rescuer – ‘I’m walking to Jask’.

After two hours of shuffling across the desert scrub she discards her shoes:

I can’t remember much about that walk; the heat was scarcely bearable. The sand seemed to be burning me up, and on two or three occasions I fell down and couldn’t go on, but every time the old man pulled me up and shouted something in his strange language.10

After 5 miles they eventually arrive at a date palm oasis, to be welcomed with traditional Arab hospitality. The tribeswomen revive her with goats’ milk. It is her first real nourishment for three days, and it sends her into a deep sleep. Meanwhile, the Belushi tribesman who has carried her original SOS message to Jask has had a torrid time. His two-day journey has involved swimming across seven shark-infested creeks, and he too is in a state of collapse when he finally reaches the telegraph station. But, by 7.30 p.m. on 5 October, the British Consulate receives the crucial telegram.

Jask was just a small fishing village until, in 1869, the telegraph station opened. It was a link for the Empire’s communications between Bushire, 500 miles away, and Karachi, 685 miles to the east. In 1886 Persia had established a customs house and garrison in the village, but the Indo-European Telegraph Department was staffed exclusively by Britons. Murray, its assistant superintendent, assembles a five-man search party, including Dr H.K. James (the department’s doctor), J.W. Burnie (a colleague) and George Wilson (Imperial Airways’ local ground engineer). Their departure is seriously obstructed by the Persian authorities and ‘sympathy seemed an unknown word in their lexicon’, as the consul’s report drily described it later.

This was the same sort of obstruction that Amy Johnson had encountered a few months earlier when she had crashed on landing at the aerodrome of Bandar Abbas on the north of the Gulf of Hormuz – the route that the less cautious Mildred should have taken. Amy had noted that the Persians loved to exert their authority and cause delay. She had been advised to respond with politeness and flattery.11

After much discussion with local government officials and policemen, Mildred’s rescue party is eventually allowed to leave port at 9 p.m. the following day. It sails down the coast from Jask and catches up with her at the date grove. In her state of near exhaustion, her first words to them are, ‘they’ve been good; they’ve been good’. She recalled later that someone replied, ‘Thank God!’, and then, ‘Never mind Mrs Bruce, we’ve got sausages for tea!’ She later wrote, ‘I shall never forget as long as I live the exquisite English voices of [the rescue team].’12

Very conscious of the threat posed by more attacks from brigands, the search party are all for an immediate return to Jask. But Mildred stands firm – not for the first, nor last time on this trip – and refuses to leave her beloved Bluebird in the desert. So, she is carried in a sort of improvised sedan chair over the 5 miles back to her aircraft. The Bluebird has some further ministration from Wilson and then, with a group of twenty Baluchis and some ropes tied to the boat, it is dragged down to what they hope is firmer sand right by the water’s edge. Some carrier pigeons are released, announcing that Mildred has been found. But only with Wilson lying on the fuselage can Mildred succeed in powering the Bluebird from its sandy incarceration, and make the one-hour flight to Jask. Wilson laconically tells Mildred he is used to the procedure, having undergone the same indignity during his service in the First World War. The rest of the rescue party endure a torrid sail back to Jask in heavy seas and against a strong headwind.

Imminent monsoons or no, Mildred is forced to spend eighteen days at Jask, awaiting the arrival of spare parts dispatched from Britain by airmail. She contracts dysentery, but is nonetheless described by her new British friends as ineffably jolly. J.W. Burnie later said in his report, ‘We’ve felt the greatest admiration for Mrs Bruce, who is certainly a woman of great nerve and endurance. Few, if any, would have met these troubles with her spirit.’

However, that spirit was to be tested further.

2

PETRE AND WILLIAMS: A POTENT GENETIC COCKTAIL

Determination and panache flowed strongly through the genes on both sides of Mildred’s family. Her father was descended from Sir William Petre, one of the consummate political operators of the Tudor era. The steel magnate Andrew Carnegie pithily judged that ‘notwithstanding many notable exceptions, the British aristocracy was descended from bad men who did the dirty work of kings, and women who were even worse than their lords’.13 Had he been thinking of Sir William, Carnegie would have been a little uncharitable – but on the right track.

Born around 1505 in Devon to a yeoman cattle farmer and tanner, William graduated in law from Exeter College, Oxford, and in 1523 became a fellow of All Souls. What set him on a path to influence and fortune was his tutoring of George Boleyn, brother of Anne. This brought him to the attention of Thomas Cromwell, who dispatched him abroad for four years to serve the nation.

Petre had an almost unique ability as a courtier and civil servant to withstand the tempests of Tudor rule. A Catholic, he served not only Henry VIII, but also Edward VI, Mary Tudor and finally Elizabeth I. He was a critical examiner of one of Princess Mary’s closest friends, when Henry was nervous of her ambitions for the throne. He zealously helped Henry dissolve the monasteries as one of Cromwell’s flying squads, together with Leigh and Layton, Tregonwell and ap Rees. Their convoy arrived unannounced at convents and monasteries, these tyrants insisting on the best accommodation available. The impact on abbots, not used to such overt hostility, was predictable. Allegations of the ‘concealment of treason’ were easy to make, and difficult to deny. And it was all under the cloak of ‘reform’.

Petre was personally responsible for the surrender of more than thirty monasteries in 1537–38. His enthusiastic toil benefited him a year later when he was given lands at Ingatestone in Essex, which had been appropriated from the manor of Gyng Abbess. These lands became (and remain to this day) the Petre family seat.

After Henry’s death, he redeemed himself with Mary Tudor by the enthusiastic prosecution of some of the supporters of Wyatt’s rebellion, which had grown out of popular disquiet about Mary’s marriage to Philip of Spain (a union of which Petre was a strong advocate). Despite his role in dismantling England’s abbeys (and acquiring some of their real estate), William was at ease with Mary’s reintroduction of Catholic influence and he secured from the Vatican a personal papal bull confirming his right to retain that property. It also, however, stimulated William to start prodigious charitable giving, whether altruistic or not.

After Mary’s death, Elizabeth reasserted the Protestant faith in England. William had a central role in organising her coronation but failing health meant he was less frequently at court. However, he carried on pulling some of the levers of state from his manor at Ingatestone. William was a mix of Blondin and Blair – dancing nimbly on the high wire of Tudor religious belief, yet as accommodating as Tony Blair in shifting his political compass in whatever direction gave him greatest preferment. In her later years, Mildred was to note sardonically, ‘He was a sensitive man. Whenever someone was being burned at the stake, he always made an excuse to the Monarch that he had a sore throat and went to his home at Ingatestone to look after the plumbing. He was very interested in plumbing.’

Petre’s family fully embraced Catholicism, despite Queen Elizabeth’s persecution. After William’s death in 1572, his widow provided shelter for many priests and missionaries. Unsurprisingly, the wonderfully Tudor Ingatestone Hall retains a warren of priest holes.

William’s son, John, was made 1st Baron Petre in 1603 by James I. While James had been selling baronetcies and peerages to replenish his depleted coffers, Petre, like his father, had been sufficiently involved in state service to earn his honour. John’s motto, ‘Sans Dieu Rien’ (‘Without God Nothing’), publicly underscored his Catholic faith. An accomplished musician, he became the patron of William Byrd, the English composer, and a Member of Parliament for Essex.

Another of Mildred’s forebears found infamy by becoming the inspiration for one of English literature’s iconic poems. Robert, the 7th Baron Petre, her five times great-grandfather, was a handsome Hanoverian philanderer. He was overcome by an obsession with Arabella Fermor, a distant cousin from another prominent Catholic family. Their torrid affair was wryly observed by their mutual friend, the poet Alexander Pope. After Petre had been implicated in a Jacobite plot, he was forced to marry Catherine Walmsley, whose lack of beauty was more than compensated by an abundance of wealth. As a keepsake of his rejected lover, at their last tryst he snipped a handful of Arabella’s hair. The episode inspired Pope’s most famous poem, The Rape of the Lock. Less than two years after his marriage, Robert died of smallpox, but Catherine gave birth to his heir only two weeks later, becoming a major charity benefactor in widowhood.

By 1910, the House of Lords held only fifty-four peers whose titles went back to the seventeenth century or beyond.14 The Petres were therefore well planted in the aristocratic firmament.

Mildred’s grandparents, the Hon. Arthur Charles Augustus and Lady Katherine Petre, raised their family of seven children – with the aid of a governess and seven staff – in Coptfold Hall, a large, isolated, cold mansion on one of the higher points in Essex (at 200ft above sea level), reached by a mile-long avenue of trees. The Petre dynasty had demolished a villa designed by Sir Robert Taylor in 1751, erecting their brick Gothic house a century later. The Coptfold estate was heavily wooded right up to the drive leading to the house’s ivy-clad western frontage. (Edwin Lutyens and Gertrude Jekyll had met in 1889 and begun their liberation of English architecture and garden design, but Coptfold had not seen their horticultural liberation.) Swathes of dense, tall rhododendrons, such a favourite of Victorian estate owners, added to its dark Gothic feel. In the grounds, the Petres built a little Roman Catholic chapel – a small-scale replica of Boulogne Cathedral.

Mildred’s father, Lawrence, was the sixth child and only son, born in 1864. There had been scant opportunity for him to escape the confines of Catholic doctrine during his education, as first he was sent to St Stanislaus College, Beaumont, a recently established Catholic boarding school at Old Windsor. From there, he moved to St Mary’s College, Oscott – a Catholic seminary in the Midlands. His father, Arthur, died in 1882 at Coptfold, but Lawrence spent holidays and later much of his bachelorhood at Thorndon Hall, a magnificent Palladian mansion near Brentwood (10 miles from Coptfold). At Thorndon Lawrence was, in effect, lodging with his uncle, William Joseph Petre, the 13th Baron, who was also a Monsignor of the Vatican and unmarried. These two bachelors rattled around in the gorgeous house, with only a brigade of staff and Lawrence’s fifteen pointer dogs for company.

Lawrence must have subsequently found living in a much less grand house – with a woman – something of a shock. That she was an extrovert American must have given even more of a start to his palate.

In the dying years of the nineteenth century, Lawrence would still have been expected to assume a role in the squirearchical rule of Essex – if not lord lieutenant, then perhaps master of the local hunt, or chairman of the Quarter Sessions, or at the very least a Justice of the Peace. But no, at Coptfold, having been elected a fellow of the Royal Meteorological Society in 1886, Lawrence contented himself with taking the Englishman’s obsession with the weather to an extreme. After pottering to his rain gauge at 9 each morning, he would record in a diary a plethora of meteorological data taken from his observatory at Hyde, on the estate. Neatly recording the readings at that time, he also noted the sky from the night before. But, ‘the site was not all that could be desired as it was somewhat hemmed in by surrounding trees. It was no more than 30 yards from a large pond.’ So, on 30 June he moved it to Coptfold House, and then on 20 July to a purpose-built observatory that seemed to suit the requirements of this fellow as it ‘was finally placed in a very exposed situation in a large meadow, and railed off from beasts’.

On 3 October 1886 there is no reference to his birthday, which fell that day, but we learn that there were very light winds, and it was very sunny after an early morning dew. It turned overcast in the afternoon, before blue sky returned in the early evening. This fastidious Victorian would have been able to enjoy a birthday gin on the terrace or in his parterre. Detailed recordings ceased at the end of 1888, and he gave up any observations on 31 July 1889. Distraction by a star of the stage, rather than sky, had begun.

***

The family of Mildred’s mother, Jennie, if not ‘below stairs’, was certainly no higher than the ground floor, and her story has faded more into the mists of time. However, it is at least as exotic. Her family had arrived on the west coast of the USA in the dramatic manner of nineteenth-century pioneers – at least in Mildred’s occasionally fevered brain, Jennie’s grandmother had joined a wagon train from her native Kentucky to seek gold in California. According to family legend, while under attack by Native American Indians in the Great Plains, cowering underneath a wagon she gave birth to Jennie’s mother, Mary. This girl grew up to marry Alonzo Williams, who became a general in the Confederate Army in the American Civil War.

Jennie Williams became an actress, making her stage debut aged 10 as Sophie in Led Astray at the Baldwin Theatre in San Francisco. Six years later, she moved to the east coast to work in Minnie Maddern’s company, and played some Shakespeare and Ibsen. Mildred later noted that her mother’s talent could encompass both ends of the dramatic spectrum. In New York, she moved into the aegis of Tony Pastor, a highly entrepreneurial theatre impresario of Spanish descent.15 Jenny Williams became a ‘soubrette’ – a flirtatious comedy character – in Pastor’s troupe. Then, the Daily Critic (of Washington) breathlessly noted, ‘Jenny Williams, a soubrette of Tony Pastor, and of late an ornament of various London concert halls, is said to be about to lead to the altar Lord [sic] Lawrence Petre of Coptfold Hall, Essex.’ Petre’s father was the Hon. Arthur Charles Augustus Petre, and well down the seniority of sons for the barony, so, while honourable, Lawrence himself was no lord. (The nuances of the English aristocracy have long been a mystery to American journalists!) However, the writer accurately reported the dynamics of the relationship.

Even at the close of the Victorian era, British aristocratic marriages were, to a greater or lesser degree, arranged. The Petre/Williams union was the antithesis and the couple had become engaged on 11 August. A New Zealand newspaper described Jennie as:

The bright and clever little actress who made her debut in San Francisco, and who made all New York by her acting as Marie in Mamzelle several years ago … She was seen by a London manager, and was carried off to England to surprise the natives by her cleverness. The nobleman’s full name is Lord Lawrence Petre, and his estate is Coptfold Hall, Islington, Essex County. He has immense parks, miles in length, and before the wedding ceremony, which occurs in the latter part of April, he will will a large portion of these fair lands to his still fairer bride.

Not many wires crossed there, then.

American journalists were agog at an American actress ‘capturing’ an English ‘lord’. A New York newspaper, the Evening World, supplied its readers with plenty of juice. Jennie had arrived in London in spring 1890 and, according to the paper, she made her debut at the newly constructed Alhambra, and also appeared at the Pavilion and Tivoli music halls. Lawrence Petre had first become stage-struck when he saw her at the Alhambra in June, ‘and was so captivated by her skirt dance, that he fell head over ears [sic] in love with her at once’.

Jennie did not so much take the London stage by storm, as sidle on, albeit beautifully, from the wings. She was absent from the programmes of all those London theatres, apart from the Tivoli. This music hall opened on the Strand on 25 May 1890 and Jennie was in the opening production. Charles Hürter, its manager, had attempted to suborn actors appearing at the London Pavilion into appearing at his new 1,510-seat ‘theatre of varieties’. In May, the Pavilion served him an injunction thwarting his plans and Hürter had to search more widely for his launch talent. Jennie was the nineteenth act on a twenty-four-star bill. George Chirgwin the ‘One-Eyed Kaffir’, hid ‘his white eye behind a Scotch hat as big as a dining room table’, but unfortunately fell ill halfway through his act. Apart from him the playlist was devoid of the most well-known stars.16

Jennie was thrust into the rollicking traditions of Victorian music hall. On the opening nights:

There were certain adventurous individuals who preferred to perch themselves on the balcony fronts … there was a natural fear that some of them might in the course of the evening make an unwelcome dive into the stalls. Some rowdy blades in the audience continued to sing a refrain through later acts. But Jennie appeared, ‘with flowing locks and pretty frocks, offered flowers for sale, and tripped merrily and gracefully on the light fantastic toe’.

The Daily News averred ‘the opening night was a complete success’.

This aristocrat’s courtship of an actress who was easy on his eye followed time-honoured fashion:

The next day he sent her a bouquet containing a dazzling diamond necklace and soon after met her. Presents of ponies, dogcarts, phaetons, Paris bonnets and the like followed, and then the engagement ring, after he had won the consent of Miss Williams’ mother, who accompanies her daughter on all professional tours.

Even if the journalist had over-burnished his story, it is clear that Petre was smitten hard and swiftly. It was all rather out of character – Lawrence was not one of the many roués who made a habit of lounging around London’s West End clubs and theatres, gambling, eating, drinking and womanising his way through a trust fund. But the diamond necklace was indeed dazzling – fifty-three graduated, circular-cut diamonds of ‘fine cut and brilliancy’, with a diamond four-stone clasp.17 Petre’s uncharacteristic fit of largesse had to be funded somehow, and 100 head of shorthorn store cattle and some horses were sent for auction, replenishing Lawrence’s bank account with nearly £1,000 – steers for diamonds, Jennie’s ancestors would have chuckled.

Land had suddenly become a liability.18 In 1877, the wheat price fell from 56s 9d per quarter to 46s 5d within twelve months. By 1886 it was down to 31s. Essex, the homeland of the Petres, was one of the worst hit counties. This was a period of retrenchment. A swathe of British aristocrats sought to bolster ailing family fortunes by marrying wealthy American women. The list is illustrious: Winston Churchill’s mother, Jennie Jerome, brought a £50,000 dowry in 1874 to Lord Randolph Churchill and the family of the impoverished Duke of Marlborough; the 9th Duke himself most notably married the coerced and heavily courted Consuelo Vanderbilt in 1895, receiving a settlement of $2.5 million for his pains. (Oxfordshire literally rolled out the red carpet for her – when she arrived at Woodstock Station for her first visit to Blenheim, she stepped on to a carpeted platform to be greeted by the mayor in full fig.)

Rudyard Kipling married Carrie Balestier in 1892; Bertrand Russell wed Alys Pearsall Smith two years later; to fill depleted coffers Lord Curzon (while Viceroy of India) in 1895 most famously married Mary Leiter, daughter of Levi Ziegler Leiter, a Chicago department store magnate. Ten per cent of all aristocratic marriages between 1870 and 1914 followed this pattern.19

Lawrence Petre was an exception: he was clearly driven by love, not thoughts of financial gain. Did he understand Jennie’s background? Chorus girls were often wined and dined and after a few drinks, some of them would boast of their illustrious ancestry. One married a man of some standing and inflated her pedigree such that he called in a genealogist. All the latter could discover was that her grandfather had played the hind legs of an elephant in a pantomime at Margate!

Imagine the Petre family’s thoughts at their only son’s choice of bride. ‘Quiet’ and ‘sensible’, and at 28, old enough to know his own mind, they had expected Lawrence to take a measured decision. But his love spoke very strongly indeed. Jennie lodged at the Hotel Cecil opposite the theatre where she had been working. The marriage went ahead at the registry office on the Strand on 28 August, only seventeen days after the engagement, with Minnie as bridesmaid. None of the formidable Petre clan attended the ceremony – in their eyes, Lawrence was turning his back on his family.

Mildred (in Nine Lives) recognised that her mother must have been discomfited by the move from the bright lights of New York to the Coptfold estate in Essex. After their marriage, Lawrence and Jennie were installed in Furniss House, the ‘secondary’ house on the Coptfold estate. It was a substantial five-bedroomed farmhouse, but far from grand – there was only one servant to attend to the needs of the lovebirds.

Lady Katherine Petre (Mildred’s paternal grandmother) was a lady of some stature and wealth, her father being the Earl of Wicklow. This was both a blessing and a curse. The strongly Protestant Katherine was not keen for her side of the family’s wealth to disappear into the hands of papists, so she created a complicated will that prevented its capital falling into the hands of any subsequent generations who worked for Rome. This meant that Lawrence never had sufficient funds to run the large estate with any financial cushion.

His match with Jennie was unequal in many ways and, as their daughter later recognised, they were ill-suited:

Mama used to say to me, ‘Your father is a gloomy man – lugubrious’. At that time I wasn’t quite sure what lugubrious meant, but I remember asking her, ‘If he’s gloomy why did you marry him?’ Quietly, but firmly she replied, ‘I married him to keep him quiet, to shut him up.’20

Whatever their later struggles, they buckled down to business and, on 24 June 1891, Jennie gave birth to their first born, Louis John, named after Lawrence’s brother who had died aged only 17. He was baptised four weeks later at the Roman Catholic Church of St John the Evangelist and St Erconwald in nearby Ingatestone. Through her rebellious teenage years, Mildred was to find her elder brother (and in particular his motorbike) very useful. Jennie bore another son, Cecil, in 1893 but he died before his first birthday.

Mildred entered the world at Furniss House on 10 November 1895, to be christened Mildred Mary when she was two months old. Mary, an unsurprising choice for a Catholic dynasty, echoed the names of two of her aunts. Jennie then suffered the anguish of another early child death and Ronald, born eighteen months after Mildred, died before his first birthday. Finally, Mildred had a younger brother whom she could later order about when Roderick Lawrence Petre was born on 1 August 1902, after the family had left the Coptfold estate for London.21 Lawrence installed his family, complete with a housemaid and a cook, in Holland House in Isleworth. Ironically, given her later career, nowadays this would be insufferably noisy, situated as it is underneath the approach to Heathrow’s runways.

By now Lawrence had inherited Coptfold Hall, but had rented it out. The profitability of agriculture, particularly in eastern and southern England, had begun to decline markedly from around 1870. In January 1885, in nearby Ipswich, Joseph Chamberlain spelled out the underlying problem for landowners, ‘I suppose that almost universally throughout England and Scotland agriculture has become a ruinous occupation.’22 This was as a result of disease, and a great influx of cheap imports, facilitated by transport improvements.

The Petres’ decamping to London coincided with the accession of Edward VII after the death of Queen Victoria. The court’s tenor shifted quickly from puritanical to sybaritic. Edward’s courtiers soon became more ‘new money’ than landed gentry. Not that he was sybaritic, but Lawrence’s relinquishing rural life was of its time. Lawrence had timed the disposal of the estate well. By 1912, nineteen peers had large estates on the market.

After the First World War, death duties rose to 40 per cent: those many young sons of the landowning classes who had enlisted had become junior officers and this group suffered disproportionate fatalities. The First World War changed the British aristocracy irrevocably. The Great War inflicted losses on them not seen since the Wars of the Roses. Where two generations of a family died within a short space of time, the impact was catastrophic. Across Europe, land prices had been declining for the last two decades and by March 1919, half a million acres were up for sale, and as the sales continued until 1922, prices soon fell substantially.23

Joseph, the 17th Baron Petre, was only one of many English Lords to put his estate up for sale in spring 1919. In reality, it must have been Joseph’s guardians since the new lord was only 5 years old, having inherited the title after his father’s tragic death early in the war. Thorndon Hall, with its estate, was leased that year to a golf club, and the Petres returned to their ancient seat at Ingatestone.24 Across Britain’s aristocracy, by the end of 1919 one million acres had changed hands.

Mildred’s ties to Essex had loosened; her wanderlust awakened. If Mildred gained her sense of adventure from her father’s family, her mother Jennie passed on the skill to charm a crowd – which Mildred was later to use to good effect.

3

PRESSURES OF AN EDWARDIAN GIRLHOOD

In her extended family Mildred was surrounded by strong and dashing male role models. A desire to more than match up to them fuelled her drive to excel. Certainly, from a young age speed held no fear and danger was to be embraced. Jennie insisted that her husband buy a small Shetland pony once Mildred reached the age of 6 and she later recalled the animal, christened Dinky, ‘was frisky and used to bolt. Everyone used to have hysterics on these occasions, I was hysterical with delight’.25

Three years later, the tigerish girl had yet to reform:

When my mother would go to a dealer to buy me a pony she would say at once, ‘Is it quiet to ride and drive?’, and if the dealer said it was, I used to nudge my mother and say, ‘I don’t want it, mother, I want another pony.’ So that showed something – I wanted to live dangerously. I didn’t want one that would just mooch along.26

Lawrence and Jennie relented and a Welsh pony pulled Mildred’s governess cart at sufficiently exciting speeds. Following the second cart being written off after careering into a ditch, the insurance company refused to provide cover on its replacement. Luckily, there were enough acres to explore the wilder limits of pony and trap handling without injuring the public.

The budding carriage driver was also toughened up by Louis, her elder brother. A keen cricketer, he used Mildred as a target to hone his bowling skills, paying her a penny an hour to be bruised by hard cricket balls, rather than tennis balls. Louis also induced her to take up fencing so that he could have an in-house adversary. So, if only for self-defence, Mildred’s hand–eye co-ordination increased apace. The Petre’s household was not one where the children sat demurely in the nursery or library.