Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

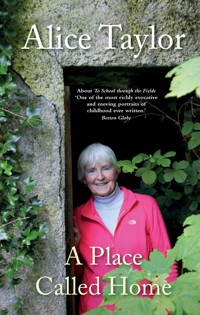

In fact, two places called home … For over sixty years, Alice Taylor has lived in the village of Innishannon, the gateway to West Cork. But her childhood was spent on a farm in North Cork, near the Kerry border, and her memories of that homeplace are vivid. Here, she recalls the sounds and smells of the farmyard, now silent; she visits her old national school, today in ruins, and her secondary, which has a new life as a cultural centre. She also writes of day-to-day life in her beloved Innishannon. With her trademark wit and wisdom, Alice takes us on a ramble around both of her homes, celebrating the places, the people and the special moments that have stayed in her heart over the years.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 159

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘In these pages, we see Taylor’s remarkable gift of elevating the ordinary to something special, something poetic, even ...’

Irish Independent on The Women

‘It’s like sitting and having a big warm blanket wrapped around you.’

Cork Today with Patricia Messinger on Tea for One

For more books by Alice Taylor, see obrien.ie

123

A Place Called Home

Alice Taylor

Photographs by Emma Byrne

Dedication

For Treasa who keeps a song in all our hearts

Contents

Introduction

Ahare changed the theme of this book. He perched himself inside my window on a small, restored pine desk that had been rescued in a battered state from an old school. After a good look around my front room he decided that this little desk, now serving as a table, was the best place for him. I grew up believing the old Celtic idea that hares are elusive, mysterious, mystical creatures with strange powers, and now that belief is fully confirmed because this hare caught my imagination, danced back through the fields to my old school – and taking a leap of faith I followed him, so changing my writing direction. In a recipe for hare soup in her well-known nineteenth-century book of household advice, Mrs Beeton sagely advised: ‘First catch your hare.’ Not an easy task! But on this occasion it was the hare who caught me and decided that I was his project. How he came to move in with me is told in a chapter of this book. But, I wondered, could the old school desk where I placed him have motivated him to lead me back across the fields to my old school?

Though not in my direct line of vision as I sit writing at my desk, I can still see him out of the corner of my eye. 10From there he can look out at the passing West Cork traffic, raise his gaze to the seasonal changing face of Dromkeen Wood while keeping a supervisory eye on me. From this little table he can see but not be seen. Having settled in, he led my thinking homewards. I had no plan to write about going back to my old school, church or farmyard, and some of the chapters of this book were already written and set in today’s world, but once that hare came on board and perched beside my desk he took over and the resulting book is a mixture of then and now. He decided that it was time to go back.

Going back can be problematic. You may occasionally peep back through a keyhole and allow colourful cameos of remembrances dance in and out of your head. But when you actually go back, memory meets reality and then you may be happy or sad as the present darns back into the past right there before your eyes. It could then well be a case of:

Remembrance wakes with all her busy train

Swells in my breast, and turns the past to pain.

From ‘The Deserted Village’, Oliver Goldsmith

During my childhood I had often watched with huge interest the eagerness and curiosity of returning emigrants. I witnessed their deep desire to see their home place and walk the fields where their ancestors had walked many generations earlier. I remember wondering what was in their minds. Where did this deep longing come from? Their 11desire to link up with the past has stayed with me, and also the memory of my parents’ and our neighbours’ understanding of and respect for their feelings. Later I saw the same response from the old people of Innishannon who, with endless patience and kindness, gave time and commitment in helping returning emigrants trace their roots. It was as if those who had remained felt an honourable commitment to the descendants of those who had had to go. Was it because those who went had so often helped those who had remained to survive hard times?

Compared to those emigrants I am ploughing a relatively fresh furrow as my journey back is within my own memory. Nevertheless, I was very curious as to how I would feel and how it would all work out. This book, like the returning emigrants, is a blend of then and now and as we travel back in time together I hope that you enjoy our shared journey. And watch out for the hare! He could lead us on a merry dance.

1

From Cockcrow to Corncrake

The sounds and smells of childhood fade into faint prints on the back pages of our minds. But an evocative smell or sound can somersault us back into a memory gallery where we have pictures of the past filed away. People who grew up by the sea fondly remember its sound, and even the sad wail of the foghorn, now gone, is full of nostalgia for them. Likewise, for me the long-gone smells and sounds of the fields and farmyard are my deepest memories of my childhood home. Going back there now opens a memory gate into that forgotten world.

Leading from the garden into the big yard was a small gate which in later years I sketched from memory and had a replica made for my garden here in Innishannon. But 14whereas my gate is solely for remembrance and to keep me happy, the original was to keep the children safe inside it and the animals at bay outside. Back then we did not call the area inside that gate the ‘garden’, but it was known as the ‘small yard’. Maybe we thought that gardens were for townies while our real garden was the land. We swung constantly off that old gate that bridged the adult gap between leisure and work. Its squeaking hinge also served the purpose of alerting us to unexpected visitors. Most of the neighbours came in through the surrounding groves or over the ditches, but those warranting a hurried, flustered inside tidy-up came in the gate. A glance out the kitchen window established if a ‘tidy-up visitor’ was approaching. However, when its squeaking became an irritant, my father oiled it silent, obliterating our substitute doorbell, until eventually the weather made its rusty voice audible again. When the Stations came around, the gate got a shiny new green coat, which sometimes a misplaced cow or calf succeeded in decorating before the big event arrived. Outside that little gate was the ‘big yard’, hedged in by an assortment of homes for an army of farm animals, all producing a variety of sounds, smells and endless jobs. Now, all the animal shelters and the endless jobs, and that small gate, are gone. But back then, that now-silent farmyard was a symphony of sound.

The first sound to break the morning silence was the dawn chorus, which usually went unheard by us humans unless my father happened to be up attending to a calving cow. Then, one night while I was up minding bonhams 15I heard it for the first time. It was an awe-inspiring concert, heralding the arrival of a new day. And with the dawn chorus came the cuckoo with his repetitive ‘cuckoo, cuckoo, cuckoo’ – which, with monotonous regularity, he repeated constantly throughout the day. Like a record with the needle stuck in the same groove he was the ongoing background chant of our summers.

But out in the henhouse another ear was listening and as the first streaks of dawn began to light up the sky he sprang into action. Our large white imperious Mr Cockerel, with his bright red crowning comb and long strong yellow legs announced, in strident tones, from his high henhouse perch, that another day was about to begin. His insistent, repeated ‘Cock-a-doodle-doo’ set off a whole menagerie of sound which continued all day, until finally, with the descending shades of darkness, he stopped and the rasping voice of the corncrake performing his evensong told us that it was time for sleep. Mr Cockerel was our morning call and the corncrake was the sound of the night.

Mr Cockerel’s early, imperious wake-up call caused his harem of hens to reluctantly ruffle their feathers and very slowly withdraw their heads from beneath their wings as they softly clucked themselves into the coming of a new day. Their enthusiasm for morning did not match the strident tones of their strutting, domineering male master. However, as they eased themselves off their high perches they emitted gentle cooing sounds of satisfied self-sufficiency. Their male master lacked their calm, serene approach to life. Still, they 16did express a whoop of victory later when they produced an egg and wished to announce its arrival. And all morning around the farmyard their triumphant calls announced their ongoing egg production. The hens believed in getting the job done early in the day and afterwards they relaxed around the yard emitting little cackles of satisfaction, as, with fluffed-out feathers and wings, they scratched for seeds of nourishment under briars and bushes. Occasionally taking time to rest, they sat with outspread wings, emitting comforting sounds of contentment. But with the approach of feeding time, they gathered in a cackling cluster around the garden gate and made their presence felt in a cacophony of demanding voices. They generously shared their mash and oats with the flocks of little birds who descended and ran in under and around their plumped-out plumage. Occasionally during the day their royal master took it upon himself to crow forth a ‘Cock-a-doodle-doo’ of domination, which his female harem ignored. His sole contribution to their world was his fertilisation of their eggs, which later led to the arrival of clutches of yellow chicks chirping around the yard behind their doting mothers. These mothers occasionally sat in the sun with outspread wings from beneath which their chicks peeped out with little chirps of contentment, a delicate, mothering, joyous sound.

At one stage guinea fowl found their way into our yard. These small, darting little black and white hens were a total contrast to their more relaxed larger cousins, emitting a sharp, high-pitched, ear-piercing screech, which caused us to grimace. 17They produced small pullet-sized eggs, which some people favoured. But their larger cousins did not take kindly to this guinea-hen invasion, so they were quickly evicted. They were short-term visitors on our farm. The large flocks of Red Sussex, White Minorca and Rhode Island Reds produced dozens of eggs, which were a constant on the kitchen table, and also part of the farm income.

The ducks and geese were far more vocal than the hens and greeted each morning with a demanding quacking and honking for release from their smelly houses. Once released, the quacking and honking became even more high-pitched. They had no time to spare for good manners, pushing each other aside and tumbling over each other in a noisy flurry of freedom as they ran down the yard with outstretched wings wanting to get to the water and the wilds. The geese foraged for their food out in the fields and along the river but came home in the evening to be housed safe from the night-prowling Mr Fox. The ducks divided their time between yard and field, constantly quacking their way around both their demesnes. They scoffed every bit of food in sight and produced large blue eggs, which required a strong palate for consumption, but were deemed excellent for baking. Both the ducks and geese over the summer months produced baby bundles of fluffy offspring, who at first waddled beep-beeping around the yard until their proud parents led them out into the freedom of the fields. In the evening all the ducks too quacked their way back to base camp for safety. Sometimes, though, roast duck joined roast chicken on our 18dinner menu, and at the end of the year the geese went to market to provide the money for Christmas, or sometimes became our most special dinner of the year.

But of all the farmyard fowl the black turkeys, who were the forerunner of the white turkeys more common nowadays, were the most vocal, emitting a high yodelling sound with the cock hitting the highest notes. While the turkey hens were gentle docile creatures, the cock was full of aggression and constantly on the lookout for assailants, even of the human kind, and this behaviour became more pronounced when fatherhood came his way. But later he replaced the goose for the Christmas dinner though his female companions were more attractive to the homan palate.

Compared to the feathered fowl, the four-legged farm animals were far more noisy and demanding. The pigs believed that the louder you yelled the more likely you were to get fed fast, and as soon as they felt the first pangs of morning hunger they commenced the most ear-piercing demands imaginable. Waves of wailing rose from their pig styes, and they jumped up, thumping their timber doors with their strong crubeens. The only way to gain silence was to land buckets of mess into their iron troughs, otherwise you felt that your eardrums could split open at their insistent thumping and screeching. So they won their case! But gaining access to that trough was an exercise in bravery, balance and, yes, pig-headedness, as the pigs from their low, four-legged, solid base made every effort to impede your progress to the trough. They were determined to help 19themselves individually and immediately to your bucket before you reached the place of communal sharing. A struggle with a pig taught you at an early age that though they might be smelly, and maybe not look too good, they had the brains and brawn to get what they wanted. But once their bellies were full, they became silent, calm and docile. These pigs provided most of our daily dinners and those who went to market oiled the financial wheels of the farm.

Whereas I found it hard to love a pig, I found calves adorable. When they were hungry and wanted to be fed, they sent out piteous bawls of appeal. They were babies, really, wanting breast or bottle, but because after the initial breast-feed of beastings from their mothers’ udders they were denied access to the cows, buckets of warm milk were the next best thing on offer. So we became the substitute mothers who answered their cries of hunger. As their cries reached fever-pitch we made our way into their midst with an assortment of buckets to appease their demands. They nudged us with their heads, but gradually we sorted them all out with the appropriate bucket, and instantly the wailing turned to the sound of satisfied slugging. Afterwards they settled down into their beds of straw until eventually released out into the fields where they kicked up their heels and took off at breakneck speed with an exultant bellow of freedom. They arrived back in the evening bawling for milk until we once again silenced them with a supply. Their mothers, who were housed in winter, also enjoyed the freedom of the summer fields, but ambled more slowly back 20for milking, morning and evening, their bellowing voices announcing their arrival. Once the cows had settled down in their stalls, the milker’s stool found firm ground beneath their full udders and the sharp sound of the first spray of their milk resounded off the bottom of the tin bucket and then mellowed to a softer tone in the deeper depths of the rising milk. This was the music of milking. At night as they calmly chewed the cud, the sound of their munching filled the stalls with their milky bovine tranquility.

The horses seldom made their presence felt except for an occasional neigh and a stamp of hooves from their stables where they were housed over winter, but in summer they came into the yard only when needed for work in the fields. Their reluctance to come back to be tackled up for work was counteracted by the rattle of a bucket, which they knew contained oats, and this enticed them to approach the person delegated to go out and ‘catch the horses’.

Their first job of the season was mowing the hay, and with two of them tackled up on each side of a long shaft, the mowing machine moved around the meadow where the whirring of the long blades though the grass sent out a low humming sound that echoed along the valley. To walk into the meadow then was to be welcomed by the sweet smell of new-mown hay. But before that mowing machine was ready for action, my father sat on a stool in the haggard sharpening its long, serrated blades with a timber-handled, grey edging stone, which he dipped in and out of a rusty gallon of water. As he worked the edging stone along the dampened blades, 21smoothing their rusty surface to a silver glint, the sound of stone against blade changed from rasping to soothing.

The endless activities of the farmyard varied with the seasons but some of the animal sounds continued all year. For us every day ended with ‘the jobs’. These consisted of milking the cows and feeding and bedding down all the other animals for the night as quietness slowly descended. Then came a blanket of satisfied silence, broken by the constant ‘crake’ of the corncrake from the grove below the house. Sometimes the sharp edges of the corncrake’s rasping voice were softened by the accompanying gentle cooing of the pigeons hiding in the branches of the surrounding trees. But despite the soft voices of the pigeons, the rasping rhythm of the corncrake predominated. Though definitely not soothing, his was the music of the night. It is quite difficult to describe the sound of the corncrake, but the pronunciation of his name, especially in a somewhat hoarse voice, maybe best conveys the erratic sound he made; the corncrake is a perfect example of onomatopoeia. When we heard his deep, throaty call, which seemed to come forth from the depths of his belly, we chanted our own little nonsense chorus:

Corncrake out late

ate mate

on Friday morning.

That grove behind the house sheltered rows of busy beehives and to stand beside them at night, breathing in the 22essence of their honeycombs and listening to their murmuring hum, was to feel close to the heart of creation.

Back then, that old farmyard was full of the sounds and smells of animals, but when I return there now and stand listening to the sound of silence it is mostly the distinctive ‘crake’ of the corncrake that echoes back through the decades. 23

Cow Dung

As a child my feet felt

The three stages of cow dung;

First warm green slop oozed up

Between pressing toes,

Poulticed sinking heels.

Later sap fermented

Beneath black crust

Resisted a probing toe.

Then hard grey patch,

Dehydrated and rough

Beneath tender soles,

Its moisture absorbed

Into growing field.

Noble cow dung fed the earth

Which gave us our daily bread.

2

As It Was in the Beginning

‘Who made the world?’ she chanted.

‘God made the world,’ we chorused back.