Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

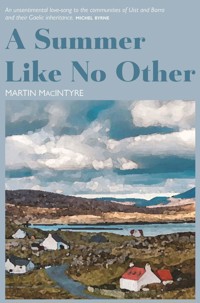

Amidst the beauty of the isles, a bond is forged that will last a lifetime. In the summer of 1978, young Colin Quinn spends time on South Uist with his uncle, Dr Ruairidh Gillies. As Scotland's World Cup hopes in Argentina stir the nation, Colin and Ruairidh forge a deeper bond amidst the beauty, isolation and rich storytelling of the Outer Hebrides.But, as the days pass, a dark cloud gathers over this idyllic summer and the local folklore capturing Colin's attention begins to hold a sobering mirror to the present. A Summer Like No Other is a moving exploration of family, connection, and the haunting forces that shape our lives. Martin MacIntyre's compelling narrative draws us deeply into that complex changing world, making us care every step of the way.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 393

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MARTIN MACINTYRE is an acclaimed author, bard and storyteller, who has worked across these genres for over twenty years; he has written eight works of fiction and three collections of poems.

In 2003 his short-stories in Gaelic and English, Ath-Aithne (Re-acquaintance), won The Saltire Society First Book Award. His novels Gymnippers Diciadain (Wednesday Gymnippers) and An Latha As Fhaide (The Longest Day) were in contention for their Book of The Year awards in 2005 and 2008, while his second story collection Cala Bendita ’s a Bheannachdan (Cala Bendita and its Blessings) was shortlisted for both The Donald Meek Award and The Saltire Literary Book of The Year in 2014. In 2018 his novel Samhradh ’78 (The Summer of ’78) was long-listed for the Saltire Fiction Book of the Year and Ath-Aithne was published in French as Un passe-temps pour l’été (A Summer Past-time) – a first for Gaelic fiction!

Martin has written two novels for younger people Tuath Air A Bhealach and ‘A’ Challaig Seo Challò’ the latter of which one The Donald Meek Award in 2013.

Martin’s bilingual poetry collection Dannsam Led Fhaileas / Let Me Dance With Your Shadow was published in 2006 and in 2007 he was crowned ‘Bàrd’ by An Comunn Gàidhealach. Since 2010 Martin has been an Edinburgh ‘Shore Poet’ and was a Poetry Ambassador at The Scottish Poetry Library 2021–23.

A new collection of poems – A’ Ruith Eadar Dà Dhràgon / Running Between Two Dragons – inspired by Catalonia and Wales, which won The Gaelic Literature Award 2021 for an unpublished manuscript, was published in April 2024 by Francis Boutle Publications in Gaelic, Catalan, Welsh and English – a first for Scottish poetry.

Another new collection, Poems, Chiefly in The English Dialect was published in July 2024 by Drunk Muse Press and launched at the Belladrum Music Festival.

Martin has been a guest at Stanza and The Edinburgh International Book Festival. He appeared at Scotland Week in New York, IFOA Toronto and was a regular contributor to The Ullapool Book Festival. He often performs at The Scottish International Storytelling Festival.

Martin was Co-ordinator of the major digitisation sound archives’ project, Tobar an Dualchais / Kist o Riches, from 1998 to 2003 and founded Edinburgh’s Gaelic community social and Arts’ club, Bothan, also in 2003. He was The University of Edinburgh’s first Gaelic Writer in Residence 2022–24. Martin is currently completing a collection of Celtic Myths for children which will be translated into many languages and published by Dorling Kindersley (DK).

First published 2018 in Gaelic as Samradh ’78

First published 2025 in English

ISBN: 978-1-80425-249-9

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by

Main Point Books, Edinburgh

© Martin MacIntyre, 2025

In honour of my uncle Dr Fergus Byrne and his late wife, my aunt, Shonna Byrne

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

May 2018

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

Bha uair ann reimhid ma-thà… once, a long time ago, when the Gàidhealtachd of Scotland and Ireland were one, there was a band of warriors, the Fèinn, who were duty-bound to protect its lands and shores from any possible invaders. Among them was a young man by the name of Oisean, Oisean mac Fhinn ac Cumhail – Oisean the son of Finn MacCool.

THE JOURNEY FROM Greenock to Glasgow Central, then north from Queen Street, was all too familiar though I’d never travelled it alone. The West Highland Line had been the usual route to Oban, twice, sometimes three times a year until my father purchased our first modest family car near the end of primary school. This wasn’t an advancement I announced with pride to my wealthier classmates. It would have been like saying, guess what lads we’ve finally decided to switch from porridge to Rice Krispies. ‘Wow, really Col!?’

God’s own island, specifically the crofting township of Eoligarry, had looked forward to Màiri Iagain Iain Mhòir’s1 return home with her brood since first she showed off her new baby, James, in the summer of 1955. I followed in ’58 and then my twin sisters, Celia and Flora, a year into the swinging decade.

My dad, Tom (or Tam) Quinn was also made most welcome, but a bus-driver’s limited holidays couldn’t always mean Barra. ‘Blackpool, Mary? Whit aboot Scarborough this year, doll?’

For Mum, time with her parents and sisters was crucial – and demanded. She couldn’t really see why anyone would choose to go elsewhere and pay good money for the privilege. Respectful daughter did though press notes into her mother’s fists on departure – ‘Dìreach son a’ bhìdh, a ghràidh.’2 None of us had ever ventured across the sound to Uist, nor indeed to any of the other Western Isles.

This year the Claymore would call briefly at Colonsay before heading further into the Minch, four hours west, to Castlebay – Barra’s ‘bustling’ capital. For the first time ever, I would not disembark here but sail a further two hours to a more languid Lochboisedale.

The thought of spending a fortnight in South Uist with my mum’s brother did not thrill me. It just wasn’t the right time, I protested – for him or me. Ruairidh was a nice enough fellow and always an interested uncle and generous with birthdays. He was also a stickler for application. Dr R J Gillies swore by hours spent sitting on one’s tòn3 and the by-product. His ‘kind’ suggestion I join him for the second half of his month’s locum on the island was as good as an order in his younger sister’s view.

‘Dè eile a tha thu a’ dol a dhèanamh?’4 her musical North Barra Gaelic demanded. ‘Certainly no exams stopping you for now, Colin, or…’

‘A job?’ I enquired faux-cheerily. This sentence was one I’d completed often in the preceding few weeks, since opting not to take second-year finals. Forced good humour once again stopped my yelling in her wan face.

She was of course correct. The ‘for now’ indicated that while, by mutual consent, my advisor of studies – Big Ron – and I had lost hope of summer success, given some harsh-reality, Ruairidh Gillies-style effort, I might still try in August. Passes in Psychology, English Literature and Modern European History would offer a scraped place in Junior Honours? ‘We’ll see Mum,’ I said.

Academic Year 1977/78 was a most sociable one at Glasgow Uni and sudden release from formal assessment had helped boost its potential greatly. With a full grant, a large, shared flat in the West End and cheapish tastes in food, alcohol and clothes, there was no desperation. As one of less than ten percent of Scottish twenty-year-olds in Higher Education – Father Cairns liked to remind us – I was well off, except that now I was on the verge of failure. So why wasn’t I scared?

Ruairidh had enjoyed none of these luxuries in the St Andrews of the ’30s and ’40s and had ‘just got on with it’. His questions would be uncomfortable. My parents, neither of whom stayed on beyond fifteen, (nor James his sixteenth birthday), had pinned considerable academic hopes on their second child. ‘Our Colin might well try Law in the end, though he’s still considering teaching.’ Really? The Colin Quinn I knew had no wish to lose hours of real life mugging the minutiae of dead tomes or babysitting bored kids with writing for which he felt scant passion.

‘And it’s not’ – my mother’s other refrain – ‘that you wouldn’t make a good doctor, if that’s what you chose to do.’

Like her husband Ruairidh, Aunt Emily – an elegant, refined lass from Perth, had chosen and indeed succeeded in medicine; her painful death eighteen months previously being the cruellest of Christmas presents.

This then was my uncle’s first locum on the island since his darling’s grave was closed. Until that point, over a period of some twenty-six years, he’d become a regular feature on the visiting professional Gael landscape; quite a small, discreet group of men. His usual routine entailed a week at home in Barra – with and at the family – then a further week’s ‘holiday’ on Uist relieving one of the local GPs; he and Dr Marr had been housemen together in Dumfries. Eric Adams, a tough Yorkshire lad, would remain on-call for all surgical emergencies. Ruairidh could cope with the rest, including most childbirth scenarios, and crucially he also had anaesthetic skills.

This year, having wrested himself from partnership in Duns, he could give the fine chaps a whole month; they would each get their first proper holiday in fifteen years. And my proposed role? To walk, fish, chat and presumably not quaff too much if Ruairidh was on-call round the clock.

So, I agreed to go; an initial commitment of a week that could be extended if all was cordial.

My ‘passage’ proved uneventful – the extra time on board the vessel a challenge to fill, and no compelling book to help achieve this. The sea was its usual grey, rolling, choppy self, but not nearly as turbulent as I had experienced it. A greasy pie and beans slid down in The Sound of Mull and behaved themselves thereafter. If any of those travelling knew me, none took the additional step of saying hello.

There was, though, a table of drunks in the bar – still high from the previous day’s cattle-sale – who were continuously hassling a guitar duo who denied knowledge of any popular Gaelic numbers. The young singer had a sweet voice and his rendition of ‘Yesterday’ was well-practised and supported with care by his friend. The boys soon tired of the facile jibes, returned their instruments to the luggage rack and donned duffle coats to escape outside. I passed them on deck near Mingulay – a first romantic visit there was still pending since delighted Catrìona MacNeil raved about the deserted island’s cliffs, between kisses, on my seventeenth birthday.

Uncle Ruairidh was on Lochboisedale pier as promised and undaunted by the hour – around 2.00am. ‘Almost had to send a stand-in,’ he joked, ‘but wee Anna cracked on and now has her fifth boy to carefully place in front of the TV to shout for Scotland.’

‘We’re on the march with Ally’s army!’ – another song the ferry pair refused to play – had been recorded weeks previously by comedian Andy Cameron. He gallusly assured us that football manager, Ally MacLeod, would lead Scotland to World Cup victory in Argentina. Our opening game, against Peru, was still over a week away.

‘Do bheatha dhan dùthaich!’5 My uncle’s more formal greeting, as he opened the neat but adequate boot of his silver MG. ‘A new acquisition, Colin,’ he added, half apologetically. ‘Always fancied one, but with a family it was never a practical consideration. Suspension’s much better than you’d think – it can handle the worst of the roads here. I see the hair’s not got any shorter!’ he then said with a funny little smile, which I answered by hooking a few strands behind my ears. ‘Just like a wee lassie’, my dad would grunt on a bad day. ‘Anyway,’ said Ruairidh, ‘how’s everyone?’

We exchanged family news as he drove, firstly to Daliburgh Cross, then right onto the main island artery. Both my older cousins were now down south I learned: Claire had recently moved – ‘with our first precious grandchild’ – to London for her husband’s job. Much of Ruairidh’s ‘our’ must still have belonged to Aunt Emily, but he made no mention of his late wife that night and nor did I.

‘Bill has sorted me a rather interesting house this year, Colin. In Eòrasdail. Bit further from Cnoc Fraoich Surgery but nothing is too far away in this machine.’ I again stated my ignorance of South Uist, much as I had when he phoned to confirm travel plans.

‘Yes, yes,’ he said, ‘I’d only been here once myself before starting locums all those years ago. Now I know the place, the South End anyway, like the back of my hand – probably better than I know Barra these days. Did you ever visit Eòrasdail in Vatersay?’

‘Nope,’ I admitted.

‘A lovely spot, Colin. I was at a wedding there once, all ghosts now. Look at that sky, there is not a star hasn’t come out for you, lad.’ He was right and The Northern Cross dazzled more on Uist’s vast celestial canvas than I’d ever previously seen it.

An island GP, Ruairidh went on to explain – with many older people still without cars – was expected to make many more home visits than their mainland counterparts, even in a semi-rural Borders towns like Duns. These houses were often located at a distance from the main road and could be challenging to find, especially in the dark. Overall, though, the Uibhistich6 were a stoic lot, and would only call out a doctor when absolutely necessary – too often a tad too late.

‘And what are you up to, Colin?’ he enquired. ‘General Arts degree, is it? Then what?’

‘Not sure.’

‘‘N d’rinn thu sgath Gàidhlig?’7 he probed. I shook my head. ‘Understand it all, just not used to speaking it that much and I couldn’t take it at school.’

‘No, the Jesuits don’t indulge such leanings; all proud Roman and erotic Greek ones with them!’ My uncle changed down gear and then roared past a pensive van in a passing-place with a vantage point over the Atlantic that promised daytime delights.

‘Got some Latin, though?’

‘An O’ Level, then…’

‘It might be worth your meeting John Boyd. He’s an old Fort Augustus pal – though his dad was a Barrach8, from Bruairnis! The Celtic lot are always on the lookout for students that are a bit different. Seonaidh’s now Departmental Head. We’ve been corresponding about my recording work, with which you are very welcome to help. This island boasts the very finest traditional singers!’

I looked at my uncle as we turned west into the village of Eòrasdail. What practical assistance could I possibly offer in the field of folklore research? Under pressure, I would just about manage to render our genealogies back a couple of generations, but beyond that you might as well plonk me on a Chopper Bike and point me down a steep brae.

My uncle, though, was on a roll. ‘And, do you know, Colin, there are still some truly remarkable storytellers here, though you always have to coax them.’

‘Really Ruairidh?’ I said, failing to stifle a yawn. ‘That’s great.’

The cloud-filled sky was bat-dark but I could see, by the lights of the little sports car, that our accommodation, Taigh Eòrasdail, was a fair size: an old square, two-storey, farmhouse at the end of the village. Ruairidh explained it had been the manager’s family home until 1909, when many of Lady Cathcart’s remaining farms or tacks were divided into crofts. Some of these original dwellings fell into ruin or were subsequently demolished – the stone transferred to more modern homes. This one had survived but was in need of modernisation.

My downstairs sleeping-quarters was more like the lounge in our West End flat, with its high-ceiling and coving, and far more spacious than my cramped brown bedroom in Greenock. It had a not altogether unpleasant mustiness about it, with brown-paper lined drawers and a camphor-wafting solid wardrobe. Both windows pulled up easily and could be secured on rusty clips. The firm double bed was pre-warmed with bricks wrapped in a worsted blanket and deliciously cosy. Four digestives with cheese and a glass of milk sat on a small bedside table. These nibbles invited me to partake without worrying about tooth-brushing, but guilt or habit, and a need to further empty my bladder, had me groping the walls around 4.00am.

The bathroom was located to the rear of the house in a corrugated-iron roofed porch. It had been added, I reckoned, within the previous twenty years, at a point, perhaps, when it was no longer convenient to empty boiled pans into a tub in front of the range, or squat to the inquisitive lowing of much less constipated cows in the byre.

That night, the light switch – neither fixed at shoulder height nor as an easily found cord – frustrated and eluded me. A brief crack in the sky let rays through the curtain-less frosted glass and beyond towards the cistern. I sat quickly for safety and an ice-bolt shot up my spine.

The deep ceramic sink offered only one built-in tap, but I could now see the thin hot-water pipe emerging from a small tank suspended above the basin. That luxury could wait until later in the morning. The cold tap was stiff, growled and burped for a good thirty seconds before delivering peaty liquid onto lathered hands. I’d stupidly left my toothpaste in the bedroom and if Ruairidh had any use for this stuff there was none lying around. A brief washout would have to do. I was merrily gurgling, when I felt the fuzzy sensation on my chilly toes – the tickle of whiskers advancing in the direction of my bony ankle, the accompanying scratchy sound on the slippery lino. My scream, Ruairidh confirmed at breakfast, could be heard in the hills of Harris.

There would definitely be mice, he said, large ones and rats in old farmhouses like these. Entry points were plentiful. He would throw down some gin-traps – lace them with that quality Wensleydale from the deli in Melrose. This, though, would mean an end to bare-footed roaming or sleepwalking, else I’d be returning home not just a little nibbled but maimed in half my lower leg.

The clang of cutlery had woken me. Through still-closed eyes, I pictured teaspoons being placed just so on saucers beside white china cups, then plain-loaf toast transferred onto a larger plate and centred on the round table. These images – of definite Greenock and Barra origin – were juicily brought to my Uist bedroom by the sizzling of bacon and fresh eggs.

A lightly sung Gaelic refrain confirmed my hunch that these culinary skills were not Ruairidh’s – any male’s in fact.

‘You got up, then!’ accused a woman, perhaps in her fifties, wearing an apron-covered, plain cotton top and brown skirt. She seemed a wiry, energetic, pleasant-smiling sort.

‘Yes!’ I admitted. I had done more than that. I’d got up and thrown some clothes on.

‘I’m Ealasaid,’ her reply, as she wiped her right hand on her pinny, before extending it formally. ‘Colin, or Cailean ’n e?’9 ‘Yea,’s e.’10 I shook her hand. What now? A kiss on each cheek? A bear hug? Perhaps not.

‘Uncle’s long gone,’ Ealasaid enthused. ‘Up with the lark to visit the sick and the infirm. ‘Eat!’ she commanded, flipping four slices of bacon and two fried eggs onto my daisy-trimmed plate.

Anna, who’d ‘cracked on’ so well, had begun bleeding at 5.30am; just after I’d fallen asleep, cocooned in my starched sheets and scratchy blanket, safe from further rodent intrusion.

Ealasaid Iain Alasdair11 (her full patronymic) was accustomed to feeding men. ‘Plenty brothers I have and always hungry, the lot of them!’ For the last three years or so, she’d also been employed on an official basis to look after Dr Marr and Mr Adam’s locums – especially the single ones. Being on-call for a week, or weeks on end, required sustenance; Ealasaid knew lots about sustenance.

‘They’re all working – mostly fishing,’ she explained. ‘Back at the prawns this last two month. Got them over and done with first, then I drove down here. Years and years since I was visiting in this house – could do with some maintenance mind you, inside and out. The Old Post Office was much more suitable. And what work will you do here now, a Chailein12?’

There it was, another reference to my assumed idle state; abject too, it seemed, in this woman’s presence, observing and savouring her industry; imagining her well-fed men out in small bouncy boats on the Atlantic. Learning of my uncle’s return to duty mere hours after he had got to bed also induced panic. So, what was I going to do now in South Uist and in the future? Ealasaid’s straight talking, and the traditional, practical, feel of Taigh Eòrasdail, demanded I address this issue immediately. People worked hard here – very hard. What ‘work’ then was Colin or Cailean Quinn going to do?

‘Don’t know,’ I answered. ‘Not sure yet. I’ll try and help somehow, I could…’

The door opened and Ruairidh Gillies entered, Gladstone bag in hand, a russet Winston-knot half-visible at his flecked collar above the shallow V of his bottle-green sweater.

‘This boy’s here to work!’ Ealasaid informed him. ‘But first of all, your breakfast. And Anna’s fine, is she?’

Ruairidh’s assurance about the woman’s haemorrhage was helpful and discreet. Ealasaid was a cousin of Anna’s husband’s and the first to hear of her complication – being so closely tied to the doctors. It was she who had convinced the tired mum to phone immediately and not leave a thing like blood-loss a minute longer. Her kind heart and Mini Clubman would head straight over there after galley-duties were completed in Eòrasdail.

Perhaps a little ahead of its time, there was no longer a scheduled Saturday surgery in Lochboisedale – a stipulation of Bill Marr’s when he arrived from Broughty Ferry in 1970.

‘Nonsense!’ he’d rebuffed those who thought such a service mandatory. ‘If they are genuinely ill, they’ll soon find us and us them.’ Mr Adams agreed.

By way of compensation, Cnoc Fraoich Medical Centre was happy to see patients until 7.00pm on a Friday evening. Ruairidh, who’d had a busier than normal week and who had worked every second Saturday morning of his post-graduate life, could have seen that late clinic far enough.

Consulting, he said, had commenced with the usual round of coughs, sniffles and sore throats, but then a woman in her early sixties appeared. Her pallor was of chalk, the only hue on her hands the dirty yellow of nicotine. She sat flanked by two younger females – daughters, he presumed – whom she banned from entering the room with her.

My uncle didn’t divulge any clinical details, but I inferred from his head shaking and our early return visit that what he’d found had concerned him.

‘What else are you going to do all day long, Colin, if you don’t come round the houses with me?’ his swift reply to my earlier enquiry. ‘You’ll enjoy it and so will I. This soul hadn’t seen a doctor in thirty years. Not once. Not even a Blood Pressure. Dear, dear. I wish she had.’

Perhaps if Ruairidh had spent a month in Uist a few years back this might have happened. People, I soon discovered, would reveal things to new doctors and new priests and new nephews that they had stored up unexplored for months or years.

The patient lived two villages south, down a narrow road very near the sea but the little sports car coped admirably. Hers was a drab pre-war croft-house, whose walls and roof needed significant attention. Perhaps as she had been flanked the previous evening in Cnoc Fraoich, two modern homes sat either side of the original family dwelling.

A range of rusted farm implements and one old wheel-less Hillman Imp, raised on breezeblocks, adorned the overgrown forecourt. As the brake screeched up, doors of both new houses flew open and two be-scarfed women emerged and darted across.

Since the weather was dry, I chose to stay back at the car, fending off remonstrations regarding cups of tea or a little something to eat that would be ‘no trouble at all’. Two collies – perhaps banished to keep me company – begged, with hungry eyes and a burst leather ball, for a game. I obliged and, using the flatter side-panel of the Imp, threw and kicked their gnawed toy at a range of deft, exhilarating, angles.

Much later, when my uncle emerged, Bob and Glen leapt on him demanding he resume the fun I had so wantonly abandoned. Ruairidh petted and talked to the dogs like old friends, but he didn’t play.

A smell of whisky from his breath and a prolonged silence on the way home in the teeming rain stirred a feeling of disquiet. What were the norms here? Where were the professional boundaries?

Our attendance at poor woman Norma’s funeral the next week allayed some of those fears.

1 Mary, daughter of Big John

2 Just for the shopping, my dear

3 backside

4 What else are you going to do?

5 Welcome to the land/country!

6 Uist folk

7 Done any Gaelic?

8 Someone from Barra

9 is it?

10 it is

11 Elizabeth the daughter of John of Alasdair

12 ‘Colin,’ when being addressed.

Chapter 2

Oisean was a likeable lad and got on well with his father, Fionn – the mighty leader of the Fèinn – and his uncle, Diarmad, their skilful swordsman. However, if these two, and many others among the band, were keen on fighting and killing, Oisean had a very different type of character.

‘RIGHT, COLIN,’ RUAIRIDH said the first Monday heading out to post-surgery house calls. ‘The normal rules of confidentiality just aren’t going to work here if you’ve to get to know the Uist people. Coming out with me will also give you a bit of an insight into what’s involved in this job; you wouldn’t be the first to switch between Arts and Medicine.’ Aha, I thought, so was this Ruairidh’s – or indeed his crafty little sister’s – plan from the start? It would have been nice had either of them consulted me about it. Perhaps it slipped their minds.

I gave my uncle a non-committal nod, then clocked a speckled cow lift its tail and splatter an enormous steaming cac13 in the middle of the village road. The heavily pregnant black one which followed, stood on it and almost skited headfirst into the ditch.

‘Of course, Colin,’ my uncle continued, ‘I’ll ask everyone’s permission first, just as I do with the medical students, and if there’s anything sensitive, well you can play with the dogs,’ he smiled. ‘Or the kids? But the people here are fine. Very little bothers them.’

A crofter in his forties had caught his leg in a bailer and was lucky not to have lost it. Fortunately, he’d suffered only an uncomplicated fracture, which Eric Adams had set and plastered ten weeks previously. There was now some concern regarding a possible infection of the newly healed skin.

This patient might reasonably have been expected to attend the surgery – as his femur had fused – but the fact he lived over a mile up a rough track (a couple of miles north of the official practice boundary) and didn’t drive made it difficult. Calum hadn’t called requesting a visit; there was no phone in the house, and he would happily have sat watching his leg fester rather than bother a doctor or bother himself to prioritise his health.

Ruairidh judged the limb to be infection-free – ‘a mild inflammation only’ – and discharged him from the repeat-call list.

The fellow’s face was particularly whiskery and his few days’ growth much greyer than his thick black hair and lamb chop sideburns. A faded image of Elvis Presley in Las Vegas sat incongruously on a neatly arranged ornament-filled dresser. I doubted his mother – a rotund soul with electric eyes – was the main fan: ‘Love me tender, RIP’ slanted in deliberate ink across the poster’s bottom edge. ‘These’ll give Ealasaid something to do,’ Calum said, handing over a sack with two skinned rabbits in it. ‘By the way, mac Sheumais Bhig14 and Joan very much enjoyed your cèilidh15 the other night.’ This was a reference to a recent visit – folkloric, not medicinal – in Kilphedar. Ruairidh had recorded two stories and a few songs with his large Uher reel-to-reel machine. I had stayed back at the house to read and think, though Ealasaid hampered much of that.

Ruairidh agreed. Iain and Joan MacDonald were very nice people indeed. ‘Iain was saying his father was full of stories and that he remembers only a fraction of them. I thought he was very good. Is that man 85 yet, Calum?’

‘Soon will be, Doctor; the day Holland thrashes Scotland. Not a patch on big brother though.’

‘Sorry?’

‘Alasdair.’

‘His big brother, you said?’

‘Yes, by age.’ Our reluctant patient was now enjoying showing off his inside knowledge. ‘Alasdair’s now quite a bit shorter than Iain, but sharp as a tack.’

‘Seadh,’16 Ruairidh checked. ‘Alasdair Sheumais Bhig, is it?’

‘Alasdair mac Sheumais Bhig is what we call him.’

‘And where does he stay?’ I could see my uncle was excited – like a little boy at the prospect of a treat.

‘You’ll have heard of Fionn MacCumhail?’ the man continued, ignoring Ruairidh’s directness. ‘He’s got a good few of those stories they say. Seumas Beag, his father, had them all and fine ghost stories. Frighten the life out of you, they would!’ To this, he added a large chesty laugh.

‘So is Alasdair in Kilphedar too, Calum?’ Ruairidh pushed. ‘Colin and I could just call in – ask after his health.’

‘You could,’ he replied with a knowing nod. ‘But you won’t get near him. Nor will he tell you a single thing. And he doesn’t speak to his brother, so don’t bother trying Iain. If Ealasaid gets these rabbits cooked tonight, they’ll feed the both of you over the weekend.’

With that, Calum retreated to raise his weak leg and listen to the news. There was no TV set in evidence or a curtain in the living-area behind which one could be resting nor had I noticed an aerial bound to the chimney. Newspapers galore though – the house was full of them with a sturdy old Bakelite wireless strategically placed in the window.

‘What do you know about Finn McCool, Colin?’ Ruairidh asked, as we drove from the rocky gravel section back onto the tarred, still narrow, road through the village. The curved concrete shelter to our right was missing its Virgin Mary, but contained flowers, candlesticks and a white prayer book. Ruairidh saw me peering. ‘A wild northerly must be due,’ he said, ‘Or else Our Lady’s gone cèilidh-ing. Do you still willingly go to Mass, Colin?’

I had accompanied my uncle to St Mary’s in Bornish the day before and would be in Garrynamonie for the chalk-white woman’s requiem, but the answer was no. ‘Anyway,’ he said, moving on. ‘Fionn MacCumhail, or Finn McCool, was a legendary Celtic warrior, both here and in Ireland. He and his troop, the Fèinn or the Fiantaichean got themselves into lots of interesting scrapes against the Lochlannaich – the Vikings. And of course, Fionn was the leader of the gang – bit like Gary Glitter, but in a more medieval macho way.’

I laughed. That singer was a fat joke. I’d never liked glam-rock and was glad his star had lost much of its brash lustre. At the time, bands like Queen and the mighty Led Zeppelin were still my thing; ‘Whole Lotta Love’ had been the Top of the Pops theme tune for years.

‘Mum never mentioned Mr McCool,’ I said. ‘She’s a good storyteller in her own way – family tragedies and all that.’

‘Tha i sin!’17 her older brother agreed. ‘Lots of these Fingalian legends were gone in Barra, even in our time! Màiri did well though speaking Gaelic to you four in Greenock. You should use it more.’ He glanced across – for quite some time, I felt, for someone driving on a narrow road. I met his stare then looked away. ‘I didn’t even consider it, Colin, when the girls were small. Claire’s keen, but as a new mum in England it won’t…’

‘Be easy,’ I supplied. ‘Or for us – you – to get anything Fingalian from Iain mac Sheumais Bhig’s big brother.’

‘We’ll see about that,’ he answered. ‘But first we’ve got to find him.’

We were in the heart of the middle district and after a third cattlegrid my uncle suddenly pulled up at a well-maintained, white-washed, house with a perfectly built peat-stack at its west-side and equally orderly chickens beyond. Not for the first time since I’d arrived, did I witness Ruairidh’s use of the art of his healing craft.

He started with a good warm chat about family – bit of teasing of the woman of the house about her having retained her good looks, whatever was her secret! Interest was then expressed and sustained on aspects of crofting: the animals in particular, what were they now sowing for them on the machair? Was silage going to help matters or be a hassle and how would that then affect feeding costs?

Husband and wife sat there placidly – daoine uasal18 – their drowned son squinting out of a square silver frame on the mantelpiece with a single un-bent Lenten palm trapped behind him. The other round wooden frames presented two beaming brides and two bashful grooms. The small woman sang at the end of the consultation – which did not include an examination, but did confirm that the new tablets were helping her sleep and dream less.

Ruairidh asked if she’d also like to try ‘Cumha Sheathain’,19 and the simple, unadorned, rendition of this elegy moved me suddenly and unexpectedly – a feeling which lingered for the rest of that day.

‘And did you ever hear of an Alasdair mac Sheumais Bhig?’ Ruairidh of course asked them, just at the right moment, before rising to leave.

Sure, they’d heard of old Alasdair – knew him well – and cautioned unequivocally against visiting him.

13 shit

14 The son of Small James

15 social visit

16 Uh-huh

17 Sure is!

18 decent people

19 A Lament for Seathan, King of Ireland

Chapter 3

There was nothing that Oisean liked more than to recite his poems and sing his songs. Oisean was famous throughout the land as the bard of the Fèinn; a bard who never killed a man.

IT WAS NOW my sixth day and Uncle Ruairidh couldn’t settle. There was a ten-year-old boy in South Boisedale with abdominal pain whom he’d seen twice in Cnoc Fraoich. Though the lad hadn’t become significantly worse, he wasn’t that much better five days later. Now he’d vomited and had a little diarrhoea: likely to be a virus – though as time went on the exclusion of something serious became crucial. Ruairidh knew several families in Uist who’d had near misses with late-diagnosed septic conditions and one who’d lost their daughter from a perforation – described by old Dr Grim as trapped wind until she collapsed.

A likely appendicitis in a child might require an Air Ambulance to Glasgow, if there were one available and it could get in through that thickening mist.

We turned abruptly south and made an impromptu visit on our way back from Uist House – the home for the elderly. Ruairidh was delighted to find the young lad up and about and with much-improved appetite and energy and obsessing, as were all the boys of his age, with Scotland’s football fortunes against Peru.

‘Bheir sinn dearg dhroinneadh orra!’20 he pronounced in quaintly idiomatic Gaelic. ‘Specially if Derek Johnstone gets a game,’ he added in English, presumably for my benefit and to confirm that his Old Firm allegiance was to Rangers.

His mother was delighted by her son’s renewed vigour and Ruairidh’s obvious concern. Iseabail reckoned she would be returning to teaching the following day. She also showed awareness of Ruairidh’s interest in Uist lore and mentioned some potential informants who had been missed when ‘The Scottish Archive people’ forayed west in the ’50s and ’60s. Alasdair mac Sheumais Bhig was not on her list.

‘You see, a Dhotair Ruairidh,’ she explained. ‘These people were still quite young then and far too busy to sit yacking into a microphone. Is it a book you’re writing, ma-thà?’

‘Perhaps in time, Iseabail. For the moment, I’m just collecting what’s still out there. I’ll deposit the lot with The Archive, but I’d like a copy to remain in Uist.’

‘Why never Barra?’ I asked, as we neared Àsgarnais.

‘Too close for comfort, Colin,’ he replied, ‘Nor nearly the same access. Did you see the wee fellow guzzling those scones, I hope he doesn’t spew tonight from all that!’

After a while in silence, bar my uncle’s slightly annoying humming, we turned towards the village of Ormacleit and followed a long, narrow road down, then up, past Clanranald’s sad ruin; the decaying walls looked as if the buttercups in the field below had spray-painted their colour on them to tart them up a bit. ‘Thig an dà latha air mòran, tha fhios’21 – Ruairidh’s take on the castle’s condition. ‘Their best days here were short-lived anyway. Fixing this place would make a good Job Creation project if anyone were interested. There’ll be two hundred in the Southern Isles working at the scheme, Colin. That’s a lot of people with unemployment at twenty percent. And it’s to end in December!’

Shortly after this, and having passed some industrious looking crofts, he asked me to open the gate to a field with a caravan in it, displaying equally modern damp and neglect. A complementary rust-pocked, off-grey, Bedford Van sat parked outside.

‘This isn’t one for you, Colin,’ he said, ‘I won’t take long!’ He didn’t and his sighing afterwards and references to the destruction wrought by alcohol in these places told enough.

‘They’ll promise you the moon and the stars,’ he added, ‘But then who feeds the kids? Especially in that midden? Over half the houses here are considered “intolerable”, a Chailein. Inverness couldn’t give a damn, and these places will bear the legacy for years to come despite the new Council’s best efforts. Right, time to organise a little pleasure.’

We continued through the next village, then back to the machair and west past the church out to Rubha Àrd Mhaoile and its broch, Dùn Mhulan. ‘This gave Bornish its name,’ my uncle said, on reaching a stone circle full of little pink flowers, ‘and that wasn’t yesterday. Iron age, a Chailein, with no shortage of pork on the table either! I hear it’s a hog-roast for the Ìochdar barbeque on Friday – if the heavens don’t open again.’

We returned to the main road, past the memorial to the fallen of The Great War, and back in through the next township, Kildonan – a most active township by all appearances including the amount of newish agricultural machinery throughout. Ruairidh then began winding his way south on a rough road by the sea – a squawk of warring birds on the rocks below us – which soon became a much bumpier machair track; the sand ridges rhythmically skelping my low-lying bum, before we turned up towards the neighbouring village. On entering Milton, we passed a farm dwelling on our left not dissimilar to Taigh Eòrasdail, except that it was larger and looked permanently occupied. Ruairidh pulled up at a small house on the opposite side with a zinc roof and a neat, felt-covered, byre.

Retired postman Teàrlach Toilichte22 appeared flattered by Ruairidh’s interest and was not in the least reticent regarding his storytelling abilities. ‘Well, I’d have a few, right enough, if I could remember them.’

That afternoon, he had overdue painting to do for a neighbour and would be in another’s the following evening for the opening game of the tournament – his house contained a colour TV and a tolerant wife. Friday would be perfect – no plans whatsoever. Of course, Teàrlach had a phone! Ruairidh would call if anything were going to delay him. Likewise, he could be contacted there in an emergency – both Ealasaid and the hospital would be given the number.

The old postie saw us to the gate and commented on my resemblance to Uncle Ruairidh but also to another Gillies brother whom he’d seen only once in his life, sitting in the saloon of The Lochearn; in 1959.

‘Yes, yes,’ Ruairidh confirmed. ‘Poor Eòin. He died the following summer – fell off a roof while building Easterhouse. Is that’ he enquired, pointing half a mile across the field, ‘Alasdair mac Sheumais Bhig’s house?’

‘The very one, a Ruairidh,’ confirmed Teàrlach. ‘But that snazzy wee machine won’t take you there. Leave it at the end of the path or you’ll never get it out! If you see a blue van…’ he began, then stopped, and allowed us to return to the MG.

‘Do we give it a go?’ I enquired.

‘Why not?’ Ruairidh answered. ‘I reckon it’s our lucky day.’

The parking spot at the path-end was empty, but there was clear evidence of a vehicle’s recent presence in the muddy verge. We left plenty of room and headed south on a rough footpath towards a tufted hillock.

Beyond the hillock was another smaller one – covered in the yellow of blooming cuiseagan.23 A scraggy sheep greeted us with her toothy smile, before darting off, as if we’d fired a gun, down and out of sight. A thin line of smoke rose ahead of us from an attractive tall clay chimney pot.

This mac Sheumais Bhig’s house was a meticulously and newly thatched two-roomed cottage. Immediately adjacent stood a similarly roofed but much smaller, hive-like, byre and behind it a felted barn – an àth.

The whitewash on the walls of the house wasn’t this year’s, though I could see that the exterior surface of the deeply set windows had been spruced more recently.

The low door had a muted brown hue but was clean, showing no flaking paint. Ruairidh knocked, and without waiting turned the handle and entered the bodach’s24 dwelling. Although it was still a relatively bright day outside, Alasdair had lit one of his Tilley lamps – its glow leaking out through a sooty frame to warm the ‘living room’ whose stove was struggling to get going.

‘Anyone in?’ Ruairidh cried, as if half-expecting the old fellow to appear by magic in his empty armchair or, as his cat did, dart out from under the bench.

‘One minute,’ was the muffled response dispatched from behind the wallpapered partition. The door then opened, allowing the briefest of glimpses through to the old man’s sleeping-quarters. A colour-tinted photograph – presumably his parents – sat centre-stage in a large wooden frame above his bed. To its immediate right hung a much darker, smaller, crucifix. In the corner I spotted – on an upended flour-chest (I reckoned) – a cruisie lamp and beside that a large enamel jug. Familiar mustiness mixed momentarily with the strong peat smell of his rùm.25

‘How are you today, Doctor? he asked Ruairidh. ‘Suidhibh!’ he commanded us both as he might a sheepdog. ‘Sit!’

Ruairidh replied that we were in good form. ‘This is my sister’s son, Cailean,’ he clarified and then added. ‘Do you think he’d make a doctor?’

I smiled nervously. This old boy gave a penetrating stare from small sea-green eyes. A stare, I felt, that could see that my entering this field would be far from straightforward. I half-coughed a ‘Ciamar a tha sibh?’26

‘Thought we’d call,’ Ruairidh continued for me. ‘See how you were.’

‘She keeps me very well. Very well indeed,’ Alasdair’s reply. ‘You’ll not want to visit too often? I’ll drop one day and that’ll be that! What else, at my age?’

No tea was offered. No biscuits hurried onto a plate. The two large kettles atop the Modern Mistress sat quietly, patiently. Alasdair did though open the door of his range and add more peat.

‘I could have a wee listen to your chest or your heart?’ Ruairidh suggested. ‘Have you had your pressure taken this last while, ma-thà?’

‘Bit late for all that now,’ his lost patient’s rebuttal. ‘When it’s all borrowed, who wants to know when it has to be given back?’

‘Young Cailean was wondering,’ Ruairidh then tried. Why this approach, I wasn’t sure. ‘If you might have any of the old stories? Làn chinn a Ghàidhlig aige,’27 he then added, by way of endorsement, though we hadn’t spoken a word of English since entering the house.

‘Ach, well…’ Alasdair began.

‘Has a doctor not got more to do than harass old men?’ barked a youngish, plumpish, short woman as she dashed in. ‘Not even had time to get dressed properly, eh?’ she scolded, and immediately advanced to Alasdair’s chair, secured two loops of his button-braces and then tucked his shirt into his dungarees before pulling down his fresh-looking fawn sweater. ‘Did you not finish that?’ she demanded, lifting an encrusted plate off a narrow wax-clothed table and emptying what she could of the contents into a large soup bowl on the floor. ‘Sceòlan,’ she hissed and a lean, black and white collie-mix, rushed in and began guzzling. ‘Soup again, I’m afraid,’ she then said, taking a lidded pot from a plastic bag before placing it on the stove. ‘But it’s hoch this time – your favourite. Dia, Dia, bidh sibh seo gu sìorraidh a’ feitheamh!’28 With that she thrust some more peat and sticks in through the top of the range.

All this, she did without acknowledging our presence further or including us in any way. I could feel Ruairidh’s awkwardness.

‘Hi,’ I tried, in English, ‘I’m Colin.’

‘Are you really?’ she answered, ‘That’s amazing! I’ve asked herself to come tonight,’ she continued to Alasdair. ‘Twins have got that stupid concert thing at the school. I don’t want to keep you up. But I’ll see you in the morning. Seo,’ she handed him two newspapers, then turned round to face us. ‘Goodbye, Doctor Ruairidh.’

My uncle rose and nudged me to do likewise. ‘Thanks, Alasdair,’ he said, turning back towards the old man. ‘See you soon.’

‘And thank you, very much, indeed, to the both of you for coming,’ replied the bodach.

‘Look after yourself, Jane,’ my uncle then murmured not making eye contact with the woman. ‘Give my regards to Ìomhair.’

‘Dash,’ he said as we walked over the hill. ‘Dash, dash. How bloody addled do I have to get, Colin. Fucking Jane and Ìomhair.’

I shot a glance at him: my grimace made obvious the distaste of his expletive.

‘We’re all human, Colin. Jane MacDonald would do well to remember that. And of course, they’ve all been trying to warn me off the old boy, but I’m so bloody thick I couldn’t see why.’

‘She might let him speak to me,’ I said.

‘Why?’

‘Because I’m not you?’

‘Really? You think she took a bit of a fancy to you, do you, eh?’

This was getting weird. Why was my uncle behaving so unpleasantly?