9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

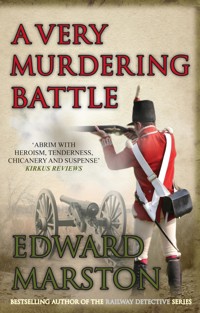

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Captain Rawson

- Sprache: Englisch

It is 1709, and Europe is in the midst of the coldest winter for a century. France is suffering profoundly: with her people starving and her army rattled by mutiny and desertions, King Louis XIV is at The Hague, searching for peace with the English on almost any terms. To assist these negotiations, the Duke of Marlborough sends Captain Daniel Rawson on a dangerous mission to Paris to seek out a package of vital information that could secure an advantageous peace deal for England. Yet when the peace talks collapse, Daniel is again embroiled in a dangerous adventure behind enemy lines And as the French army regains its strength and a bloody encounter looms at Malplaquet, Daniel faces his most murdering battle yet.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 491

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

A Very Murdering Battle

EDWARD MARSTON

To Judithwith love and thanksfor the way that she fought every battlein the War of the Spanish Succession beside me.

Contents

Title PageDedicationCHAPTER ONECHAPTER TWOCHAPTER THREECHAPTER FOURCHAPTER FIVECHAPTER SIXCHAPTER SEVENCHAPTER EIGHTCHAPTER NINECHAPTER TENCHAPTER ELEVENCHAPTER TWELVECHAPTER THIRTEENCHAPTER FOURTEENCHAPTER FIFTEENCHAPTER SIXTEENCHAPTER SEVENTEENCHAPTER EIGHTEENCHAPTER NINETEENCHAPTER TWENTYBy Edward MarstonCopyright

CHAPTER ONE

January, 1709

France was in the grip of the coldest winter for a century. Rivers froze, animals died in vast numbers and the seed corn for the next harvest perished in the ground. An almost perpetual frost blanketed the country. Icy fingers closed around the throat of Paris and tried to throttle it, choking off its commerce, squeezing the breath out of its administration and killing off at random the old, the infirm, the sick, the poor and anyone unable to find adequate protection against the relentless chill. It was the worst possible time to visit the French capital but Daniel Rawson had no choice in the matter. While his regiment was shivering in its winter quarters, he’d been dispatched into enemy territory on important business. It was not an enticing prospect. What made the visit bearable was the fact that he was able to stay with an old friend in a house that offered him a warm welcome and a roaring fire.

Ronan Flynn tossed another log onto the blaze, then appraised him.

‘What, in the bowels of Christ, has got into you, man?’ he asked. ‘Only a lunatic would come to Paris in this weather. It will freeze your balls off.’

‘It’s the same wherever I’ve been,’ said Daniel, ‘and I hear that England fares just as badly. The Thames is solid ice and they hold a frost fair on it.’

‘Then at least they get some pleasure out of the winter. There’s none of that for us, Dan. The last harvest failed and we’re facing a famine. Think what that means for me. I’m a baker now, remember.’

Daniel nodded. ‘How could I ever forget?’

Flynn was a tall, rangy, raw-boned Irishman in his forties with long, grey hair that curled at the edges and which hung so low over his forehead that he was always brushing it back. He and Daniel had once fought together in the Allied army but his most recent military service had been in one of the Irish regiments in the pay of the French. The change of sides had not affected their friendship because the bond between them was too strong. After a rescue on the battlefield, the Irishman owed Daniel his life and would always be indebted to him. For his part, Daniel admired the ebullient Flynn both as man and soldier. Also, in view of what happened during his last stay at the house, he had reason to be eternally grateful to his old comrade.

‘Bakers need flour,’ said Flynn, worriedly, ‘and there’s little to be had. The Treasury tried to buy corn from the Beys of North Africa but they were stopped from shipping it to France by squadrons of British and Dutch warships.’

‘You can’t expect me to apologise for that, Ronan. War is war.’

‘And bread riots are bread riots.’

‘I’m sure you’ll survive somehow.’ Seeing the anxiety in his friend’s eyes, Daniel quickly changed the subject. ‘It’s wonderful to see you and your family looking so well. Charlotte is as beautiful as ever and I can’t believe the change in Louise. She was a babe in arms when I last saw her. How old is she now – three?’

Flynn brightened immediately. ‘She’s almost four, Dan, but she gives herself such airs and graces that you’d take her for a young lady, so you would. Louise can be a little devil sometimes and I love her for it. The girl has got such spirit.’

‘She inherited that from her father.’

‘Yes, she has Charlotte’s looks and my mettle. Thank goodness it’s not the other way round,’ Flynn went on with a laugh, ‘because I’m an ugly bugger and my dear wife – God bless her – is placid as they come. That’s why I married her. After all this time, mind you, I still don’t know why she married me.’ He laughed again then narrowed one eye as he looked at Daniel. ‘But talking of beautiful women, what happened to that darling creature you brought here the last time you stayed under our roof? She had the face of an angel. What was her name – Emilia?’

‘Amalia,’ said Daniel, fondly. ‘Amalia Janssen.’

‘I can tell from your voice that she set your blood racing. What man could resist her? You shouldn’t have let her slip through your fingers, Dan.’

‘I didn’t.’

Flynn’s interest quickened. ‘You’re still in touch with her?’

‘I always will be, Ronan.’

Daniel gave him a brief account of the way that his friendship with Amalia Janssen had matured into something far more significant and satisfying. He’d first met her when he’d been sent in disguise to Paris to track down her father, Emanuel, a celebrated tapestry maker employed at Versailles by Louis XIV. Unknown to his patron, Janssen had also been working as a spy on behalf of the Allied army and, when exposed, he was promptly imprisoned in the Bastille. It fell to Daniel to rescue him from captivity, then spirit Janssen, his daughter, his assistant and his servant all the way back to Amsterdam. Such a feat would have been impossible without the help and advice of Flynn, who sheltered the fugitives until they were ready to sneak out of the city by means of cunning stratagems devised by Daniel.

Flynn was a good listener, sipping wine and tossing in the odd question to keep the narrative flowing. He was delighted to hear that his friend had finally found someone with whom he was ready to share his life.

‘You’ve changed, Dan,’ he teased. ‘When we bore arms together, you had an eye for the ladies and took your pleasures where you found them. The handsome Captain Rawson broke lots of female hearts in his time.’ He smothered Daniel’s interjection with a raised palm. ‘Yes, I know, I was just as bad – far worse, if truth be told. I had more than my fair share of conquests and I shudder at the thought of what I once was.’ He looked upwards. ‘May the Lord forgive me my sins!’ he said with feeling. ‘I was a different man then. It was before I met Charlotte and realised what it was like to love someone with every fibre of my body. When Louise came along, my life felt complete for the first time.’

‘I’m very happy for you, Ronan – and full of envy.’

‘Does that mean you’ll follow my example and give up soldiering?’

‘Oh, no,’ said Daniel, seriously, ‘I’d never do that.’

‘You could if you had real sympathy for your wife. See it from her side. Marriage to an army officer is a species of hell. You never know from one day to the next if your husband is still alive. The constant anxiety will wear any woman down.’

‘This war will be over one day.’

Flynn raised an eyebrow. ‘How many years have you been saying that?’

‘Peace talks are taking place at this very moment.’

‘I’ll wager anything you like that they’ll come to nothing. You know that as well as I do. Be honest, Dan – can you really sniff peace in the air?’

Before Daniel could reply, Charlotte came down the stairs and emitted a sigh of relief. Wearing a plain dress that showed off her shapely figure, she had a shawl around her shoulders. She didn’t seem to have aged at all since the last time Daniel saw her and looked more like Flynn’s daughter than his wife.

‘I finally got her off to sleep,’ she said.

‘That was Dan’s fault,’ argued Flynn, lapsing into the French he habitually used in conversation at home. ‘That doll he brought for Louise got her so excited that I thought she’d be up all night.’

‘It was a lovely gift. Thank you, Daniel.’

‘No thanks are needed,’ said Daniel. ‘It’s such a pleasure to see her again.’

‘Don’t leave it so long next time.’

Charlotte sat beside them and warmed her hands at the fire. Fluent in French, Daniel chatted happily with her, struck yet again by the fact that such an attractive young woman had somehow met and married a wild Irishman with a chequered past who was all of eighteen years older. It was an unlikely union but man and wife were supremely contented with each other. When Daniel asked how dire the situation was in Paris, she became more animated, gesticulating with both hands and bemoaning the economies they’d been compelled to make.

‘It’s been a real ordeal,’ she said.

‘We’re better off than many, my love,’ Flynn reassured her.

‘That’s no comfort to me, Ronan.’

‘It ought to be.’

‘I wonder how much longer we can go on like this.’

‘There’s bound to be a change in the weather soon,’ said Daniel, more in hope than with any certainty. ‘Everything will be back to normal then.’

‘I’ve prayed for that to happen a hundred times or more,’ she said, sadly, ‘but God doesn’t listen to me. Madame Vaquier thinks that this terrible winter is his way of punishing us.’

‘For what?’ asked Flynn with mild outrage. ‘Why punish me when I lead such a blameless life? I’m the next best thing to a saint.’

Charlotte giggled. ‘I wouldn’t say that, Ronan. Saints don’t use some of the rude words that you do. But,’ she went on, turning to Daniel, ‘we mustn’t bore our guest by complaining about our woes. What brings you to Paris this time, Daniel?’

It was a question that Flynn had the sense not to ask, knowing that his friend would, in all probability, be there to gather intelligence and not wishing for any further detail. He preferred to offer unconditional hospitality.

‘Well?’ pressed Charlotte with an enquiring smile.

Daniel weighed his words. He was about to speak when he saw movement out of the corner of his eye. He flicked his gaze to the staircase where Louise, the bright-eyed child with her mother’s arresting loveliness, was sitting on a step in her nightdress. She was hugging the gift that Daniel had brought for her and was clearly entranced with her new doll. The girl unwittingly provided him with his cue.

‘I came all this way to give Louise a present from Holland,’ he said, beaming at her. ‘Can you think of a better reason?’

Encrusted with frost, the palace of Versailles looked rather forlorn, its magnificence dimmed, its celebrated gardens turned to a white wilderness, its countless fountains no more than slabs of ice and its statuary deformed and diminished by the bitter weather. A veritable army of servants was deployed to keep the fires blazing in the rooms and the bedchambers but the long, wide corridors were avenues of gnawing cold. Huddled into a corner, the courier pulled his cloak around him and wished that he could slip off to the kitchens where there was sure to be a reviving warmth and even the possibility of a hot drink. Orders were orders, however, and he was forced to obey them. He was a dark-haired man of medium height and middle years. A regular visitor to Versailles, he was usually glad to leave it. Not on this occasion. When he glanced through the window and saw snow beginning to fall, he quailed inwardly. It would be a testing ride to Paris and one that he would rather not make, but his inclination carried no weight. The work was too well paid to ignore and too important to postpone. He was committed.

Everything was done by numbers. He was not allowed to move until the various clocks began to strike eleven times. Only when their echo had died away could he leave his post and take the second passageway to the left. Just beyond the third door on the right was a small oak chest. Inside it was the package for him. The courier never knew who put it there or who would take it from him in Paris. He was merely an intercessory. Even the signals used were in the form of numbers, allowing him to deliver the package to the right person in the right place at the right time. Conversation was unnecessary. What was in his secret cargo, he had no real notion. It was not his place to speculate. Discretion was absolute. That had been impressed upon him from the start.

It seemed to be getting even colder. Cupping his hands together, he blew into them to give his palms fleeting warmth then tucked them under his armpits. Time hung heavy. The wait became increasingly tedious. His fear of being discovered and challenged grew more intense. Then, at long last, he heard the clocks begin their choral tribute on the hour. One, two, three, four – he stamped his feet in time to the melodic chimes. Five, six, seven, eight – here was action at last. Nine, ten, eleven – he heard the crucial number fade into silence then he was off. Marching along the corridor, he turned left at the appropriate place then counted three doors on the right. Stopping beside the oak chest, he looked up and down to make sure that nobody was watching. It was the work of a second to lift the lid of the chest, snatch the package, hide it in a pocket and replace the lid.

When he stepped out of the building, he discovered that the snow had enlisted the help of an accomplice – a knifing wind that made the flakes swirl and that stabbed at his face. Pulling his hat down over his forehead, he hurried to the stables. His horse was even less willing to go out in a snowstorm and bucked mutinously. Once in the saddle, he mastered it with a fierce tug on the reins and a sharp dig with both heels. It emerged resentfully from the stables and trotted off into the wind. So intent was he on his mission that the courier didn’t notice the two men concealed in the shadows. As he went past, they stepped out to watch. The younger of them was impatient.

‘Let’s go, Armand,’ he urged.

‘There’s no hurry,’ said Armand, lazily. ‘We know where he’s heading and his horse will leave plenty of hoof prints in this snow. We only need to get closer when we near Paris.’

‘Do we kill him or take him alive?’

‘We kill him, Yves. He’s only a messenger and can tell us nothing. The man we’re after is the one awaiting the delivery. He’s the real catch.’

By the time that Daniel reached the little shop, the snow had stopped falling. It was, however, still more than cold enough to justify his thick cloak, wide-brimmed hat and gloves. He rode with a blanket over his horse so that it had some insulation against the elements. Paris was fairly empty at that time of the evening and nobody saw him turn into the side street where the premises were located. Since the shop was closed, he banged on the door and the owner was instantly roused. The door opened to reveal the diminutive figure of Claude Futrelle, the apothecary, white-haired and with a wispy, white beard. As he studied his visitor through bloodshot eyes, his voice was flat and his face motionless.

‘The shop is closed, monsieur,’ he pointed out.

‘I didn’t come for medicine,’ said Daniel.

‘Then I can’t help you.’

‘I was told that you could, Monsieur Futrelle.’

‘You were misinformed.’

‘I think not.’

‘Be off with you.’

‘Your suspicion is understandable.’

‘Farewell, monsieur.’ When the apothecary tried to close the door, Daniel grabbed it with a firm hand and held it ajar. ‘Leave go,’ said Futrelle, angrily.

‘Not until we’ve discussed the symptoms.’

‘You said that you didn’t want medicine.’

‘I’m not talking about my condition,’ said Daniel, ‘but that of France itself. It’s eaten away with a disease that no apothecary can cure. Don’t you agree?’

Futrelle looked at him anew with a mixture of curiosity tempered by caution. He asked a few apparently irrelevant questions and Daniel gave him the correct answers. They were talking in code. Once the old man was satisfied with his visitor’s credentials, he told Daniel to tether his horse in the stable at the side of the property. The two men then adjourned to a room at the back of the shop and sat either side of a table. A crackling fire helped Daniel to thaw out. Since there was still a vestigial suspicion in the apothecary’s eyes, Daniel produced a letter from inside his coat and handed it over. Reading it by the light of the candle, Futrelle gave a nod. Daniel was accepted.

‘You are welcome, monsieur,’ he said.

‘Let us remove all trace of this,’ said Daniel, taking the letter from him and holding it over the candle until it was ignited. ‘We don’t want anyone else knowing who sent me.’ He tossed it into the fire and it was soon consumed. ‘There – it’s as if it never existed.’

‘One can’t be too careful.’

‘Pierre Lefeaux taught me that.’

Futrelle was startled. ‘Pierre died years ago.’

‘I know,’ said Daniel. ‘I found him hanging from the rafters beside his wife. He obviously hadn’t been careful enough.’

‘Someone betrayed him. He was a brave man.’

‘I’m glad to see that you are equally brave.’

‘Not me, monsieur,’ said Futrelle with a self-deprecating laugh. ‘Brave men don’t tremble as much as I do, nor fear for their lives every time a stranger comes into the shop. Because I’m terrified of meeting Pierre’s fate, I trust nobody.’

Daniel warmed to the old man. He was one of the go-betweens employed by the Allied army, people with a strong enough grudge against France to help its enemies by acting as repository for intelligence gathered by agents in the city. Futrelle had no idea what was in the various missives that he stored before passing them on at regular intervals. He just hoped that he was helping a cause in which he passionately believed and accepted – albeit nervously – the consequent risks.

‘I have nothing for you at the moment,’ he explained, ‘but, as it happens, I expect a delivery this very day. Your arrival is timely.’

‘It’s no accident,’ said Daniel. ‘I was warned to be here on the thirteenth of the month because that’s the date when word is sent from Versailles. I just hope that it gets through. This weather would deter most couriers.’

‘He’ll be here, monsieur, I assure you.’

‘Will he come to the shop?’

‘That’s far too dangerous. The exchange is some distance away.’

‘Do you always take the delivery?’

‘No,’ replied Futrelle, ‘I have a number of agents and we take it in turns to be there on the thirteenth of the month. January is always my turn.’

‘I’ll go in your place.’

The apothecary smiled gratefully. ‘Then you are doubly welcome, monsieur. I’d hate to go out on a night like this. I have potions to cure almost anything but being chilled to the marrow is a condition I cannot relieve. And I am of an age when I feel the cold more keenly.’ He lowered his voice. ‘He’ll need to be paid first.’

‘I have plenty of money with me.’

‘You obviously came prepared.’

‘Prepared and eager,’ said Daniel. ‘Teach me the code.’

Once on his way, the courier had found his journey less onerous than he had feared. The snowstorm eased and the wind became less capricious. It was still not a pleasant ride but at least he no longer had doubts about reaching his destination. Paris was some ten miles distant from Versailles, so he had ample time to get there. He stopped at a wayside inn to take refreshment and to rest his horse. With hot food and a glass of brandy inside him, he felt able to face the next stage of the journey. It never occurred to him that he was being trailed by two men. No sooner had the courier ridden off than the pair stepped out of the inn and made for the stables. Mounting their horses, they gave pursuit, staying close enough to keep him within sight and far enough behind him to avoid arousing suspicion.

When he reached Paris, the courier had hours to spare and decided to make the most of them. After picking his way through the deserted streets, he turned into a courtyard, dismounted, tethered his horse to a post then rang the doorbell of a house. Recognised by the servant who opened the door, he was admitted at once. The two men arrived in time to witness his disappearance.

‘Do we follow him in?’ asked Yves, impulsively.

‘There’s no need,’ said Armand.

‘But he’ll be making his delivery.’

‘He won’t be handing over any correspondence here. He’s making a visit of a very different kind. This place is a brothel.’

‘How do you know?’

Armand grinned. ‘How do you think I know?’

Yves was indignant. ‘Do we have to stay freezing out here while he’s between the thighs of some greasy harlot?’

‘Show some compassion,’ said his friend, tolerantly. ‘Let him enjoy it. Before the night’s out, he’ll be dead.’

Even the meeting place had a number. Les Trois Anges was an inn in one of the rougher parts of the city but there was nothing angelic about it. Cluttered, low-ceilinged and dirty, the bar was gloomy and malodorous. The fire did little to dispel the abiding chill. Needing to make the exchange at precisely eight o’clock, Daniel arrived ten minutes early and bought himself a drink. The weather had robbed the inn of most of its habitués, so he had a choice of tables. He took one near the door, then casually put six coins on the table before arranging them in a triangle. It was all the identification needed. He sipped his wine and waited, checking, as usual, for any other exits from the building. In the event of an emergency, it was always wise to have an alternative means of leaving a place. The precaution had saved his life on more than one occasion. He looked up as the door swung open but it was not the courier he was expecting. The big, slovenly man who stumbled in was too early and hardly a person to be trusted with so important a task. His torn clothing, massive hands and fearsome gaze suggested someone used to manual labour. He would never have been allowed near Versailles.

Hunched over his table, Daniel used his arms to shield the telltale money. It was when a distant clock began to boom that he sat up and exposed the triangle of coins. The courier was punctual. He came in with a quiet smile on his face, walking past Daniel and appearing not to notice the signal on the table. He ordered a glass of brandy and stood at the bar as he sipped it, trading banter with the landlord. When he’d finished his drink, he bade farewell and headed for the door. Daniel was ready for him. Passing the table, the courier slipped the package into his hand and received a small purse in exchange. He let himself out. Daniel, meanwhile, had secreted the package in a pocket inside his cloak. It was all over in seconds. Nobody in the bar noticed anything untoward but the eyes at the window were more observant. They saw what they had come to see and acted accordingly.

Daniel lingered for a few minutes before downing his wine in one last gulp. Then he swept up the coins, thanked the landlord for his hospitality and went out. Intending to reclaim his horse, he was surprised to be confronted by two men who blocked his way. One of them held a pistol on him while the other extended a hand.

‘I’ll thank you for that package, monsieur,’ said Armand.

Daniel was unperturbed. ‘You are mistaken, my friend. I have no package.’

‘It was given to you by the courier.’

‘What courier? There’s clearly a misunderstanding here. I received nothing from anybody. I was merely enjoying a drink. If you doubt me, ask the landlord.’

‘We followed him from Versailles,’ explained Armand, ‘and the trail ended here – with you. As for the courier, the trail ended altogether for him.’

The two men moved apart so that Daniel could see the figure sprawled on the ground behind them. Enough light was spilling through the windows of the inn for Daniel to see that the courier’s throat had been cut from ear to ear and that he was lying in a pool of blood. His visit to Les Trois Anges had cost him his life.

Yves raised the pistol and aimed it at Daniel’s head.

‘We’ll ask you one last time, monsieur,’ he said, menacingly. ‘Hand over that package while you’re still alive to do so.’

CHAPTER TWO

Daniel needed no convincing. If they could kill the courier with such casual brutality, they’d have no compunction about sending Daniel after him. He therefore came to an instant decision. Since he couldn’t bluff his way out of the situation, a show of compliance was required. With a shrug of defeat, he reached inside his cloak.

‘You have the advantage of me, messieurs,’ he said, resignedly.

‘Hand it over,’ insisted Yves.

‘I will, I promise.’

But it was not the package that he brought out. What emerged from his cloak was a dagger that flashed upwards and pierced the wrist of the hand holding the pistol. As Yves let out a cry of pain, the weapon jerked skywards and discharged its bullet harmlessly into the air. Daniel pushed him hard in the chest and he tottered back, tripping over the corpse and falling to the ground. Yves was more concerned with stemming the flow of blood from the wound than anything else but Armand wanted revenge. His hand went to his sword. Before the man could draw, however, Daniel kicked him in the groin, making him double up in agony, and shoved him on top of his friend. While the two of them struggled to get to their feet, they rid themselves of a stream of expletives. Daniel didn’t hear them because he’d already run off to his horse and mounted it at speed. Not knowing where he was going, he galloped off into the night.

Armand and Yves were soon in pursuit. Cursing their folly and mastering their pain, they delivered a valedictory kick at the dead courier before staggering across to their horses. Though Daniel had a good start, there was an immediate problem. As he clattered over the cobbles, his horse’s hooves echoed along the empty streets and gave a clear indication of his route. All that the two enraged men had to do was to follow the sound. There was a secondary consideration. Daniel was riding blind while they, he reasoned, probably knew the city well. They’d be aware of any short cuts and might be able to intercept him. Since he couldn’t outrun them, he was faced with a choice. He could either hide somewhere or turn and fight. The obvious refuge was Claude Futrelle’s shop but Daniel was unsure of finding it in time and, in any case, wanted to lead his pursuers away from the apothecary. It would be unfair to put Futrelle in jeopardy. Apart from anything else, the old man would certainly break under torture and endanger the lives of other agents. The complex network of spies simply had to be protected.

Daniel reined in his horse and listened. The sound of furious hooves could be heard in the distance. They were after him and wouldn’t give up until they caught him. The decision was made for Daniel. He had somehow to dispose of them before they killed him and recovered the documents he was carrying. Kicking his mount into action again, he rode on until he came to what appeared to be a commercial district. Warehouses loomed up on both sides of the road, then he passed a timber yard. When he came to a turning on the left, he took it, only to discover after fifty yards or so that he was in a cul-de-sac. Instead of being dismayed, Daniel was pleased. Here was a possible chance of turning the tables on his enemies. He rode back to the corner, dismounted and lurked in the shadows. Armed with a dagger and a pistol – and with long experience of escaping from such predicaments – he felt that the advantage had now tilted in his favour. He’d not only chosen the ground for combat, he had the element of surprise.

As the two riders approached, Daniel could hear them slowing their horses so that they could search for their quarry. He waited until they got closer then put his plan into action. Slapping his horse on the rump, he sent it galloping down the cul-de-sac. Armand and Yves responded at once, drawing their swords and spurring their mounts on. Pistol in hand, Daniel was ready for them. When they came hurtling around the corner, he let them get within yards of him before stepping out and firing his weapon at the nearest rider. The bullet hit Yves in the middle of the forehead, blowing his brains out and knocking him from the saddle. As it bounced on the ground, Daniel leapt forward to snatch up the dead man’s discarded sword. Armand was shocked at the loss of his friend and infuriated that they’d ridden into a trap. Yanking on the reins, he pulled his horse in a semicircle then jumped to the ground. He could only see Daniel in silhouette but it was enough to set the blood pulsing through his veins. Sword in hand, he stalked his prey.

‘Who are you?’ he demanded.

‘Why not come and find out?’ invited Daniel, coolly.

‘Yves was my friend. You’ll pay for his death.’

‘Take care that you don’t pay for the courier’s death. I’m not an unsuspecting man leaving an inn and there are no longer two of you against one. We fight on equal terms, monsieur, and that means you will certainly lose.’

Armand brimmed with confidence. ‘There’s no hope of that happening.’

‘We shall see.’

They were now close enough to size each other up, circling warily as they did so. Daniel knew that his adversary would strike first because the man was fuming with rage and bent on retribution. Armand didn’t keep him waiting. Leaping forward, he tried a first murderous lunge but Daniel parried it easily. Their blades clashed again and sparks flew into the air. Daniel was testing him out, letting him attack so that he could gauge the man’s strength and skill. Evidently, Armand was a competent swordsman but he had nothing of Daniel’s dexterity, still less his nimble footwork. Each time he launched himself at his opponent, he was expertly repelled because he was up against a British army officer who had regular sword practice. Aware that he couldn’t prevail, Armand became more desperate, slashing away wildly with his blade and issuing dire threats as he did so. Daniel remained calm and chose his moment to bring the duel to a sudden end. Unfortunately, the frosted cobblestones came to Armand’s aid.

As Daniel poised himself for a final thrust, his foot slipped and he was thrown off balance. Armand seized his opportunity at once, putting all his remaining power into a vicious attack that drove Daniel back until his shoulders met a wall.

Laughing in triumph, Armand went down on one knee to deliver what he felt would be the decisive thrust but Daniel was no longer there. Moving agilely sideways, he let his opponent’s sword meet solid stone and jar his arm. Armand’s moment had gone. A slash across the back of his hand forced him to drop his weapon, then Daniel thrust his blade into the man’s heart. With a gurgle of horror, Armand slumped to the ground and twitched violently for several seconds before expiring. The commotion had aroused nightwatchmen in warehouses nearby and loud voices were raised as they came to investigate. First on the scene was a man with a lantern held up to illumine Daniel’s face. Others soon converged on him. There was no time to search for his horse at the other end of the street. Tossing the bloodstained sword aside, Daniel pushed his way past the newcomers and melted quickly into the darkness, sustained by the thought that he’d saved the vital package and done something to avenge the murder of the hapless courier.

Army life had accustomed Ronan Flynn to having his sleep rudely disturbed. He was used to being roused in the early hours of the morning to make a hasty departure from camp. Rising well before dawn, therefore, was no effort for him and he’d settled into a comfortable routine. He awoke in the dark, got out of bed and groped for the clothes he’d left on the chair. Once dressed, he gave his wife a token kiss on the forehead, then tiptoed out and crept down the stairs. When he’d lit a candle, he made himself a light breakfast and reflected on the changes in his life. The visit of Daniel Rawson had left him with mixed emotions. Flynn was glad that his soldiering days were over and that he was now happily married to a gorgeous young woman in his adopted country. He had a new occupation and a new set of responsibilities. At the same time, however, he felt that something was missing. The sense of adventure embodied in Daniel had a heady appeal and he was reminded of the thrill of courting danger at every turn. While he had no wish to return to the army, he’d begun to feel regrets that had been dormant for years. Work as a baker was safe, undemanding and profitable. Yet it was also mundane and repetitive. It lacked the excitement and the camaraderie he’d found when in uniform.

Shaking his head, he tried to dismiss such thoughts. He knew who to blame. ‘Damn you, Dan Rawson!’ he said to himself. ‘Why the devil did you have to come to Paris and stir up memories I’ve tried so hard to forget?’ He addressed his mind to what lay ahead. When he got to the bakery, the ovens would already be lit by his assistant and Flynn would be able to start making loaf after loaf. It was a staple food that people needed every day. Providing it gave him satisfaction and, after all this time, he still savoured the tempting aroma of fresh bread. The bakery was owned by his father-in-law, Emile Rousset, but he’d been happy to let Flynn gradually take charge. It was a far cry from the menial jobs he’d done as a boy in his native Ireland. Having mastered his new trade, he applied himself to it and soon built his reputation. He was liked and respected by his customers for his excellent bread and for his cheery disposition. It was something of which Flynn could be justly proud.

Breakfast over, he put on his ratteen coat and reached for his hat. With an old cloak around his shoulders, he was ready to step out of the house into another wintry day. He carried the lighted candle, cupping a hand around the flame to prevent it from being blown out. In the stable, he set the candle up on a shelf and went to work in its flickering circle of light. After harnessing the horse, he had difficulty persuading it to go between the shafts of the cart and had to swear volubly in French at the animal. It was only then that he realised he was not alone in the stable. Something seemed to be moving under the pile of sacks on the back of the cart. Holding the candle in one hand, he used the other to grab a sickle that was hanging on a wall.

‘Come out of there,’ he ordered, standing over the cart.

As the sacks were peeled off one by one, Flynn watched with his weapon held high and ready to strike. Angry that someone had dared to trespass on his property, he resolved to punish the interloper. When the final sack was moved aside, however, a familiar face came into view. Daniel gave him an apologetic smile.

‘Good morning, Ronan,’ he said. ‘I hope you don’t mind me bedding down here for the night. I had a spot of bother.’

The Duke of Marlborough divided opinion. While everyone agreed that he was a supreme strategist on the field of battle, there were those who criticised him for what they perceived as his characteristic meanness. Compared to other generals in the Allied army, he maintained rather modest quarters and was quicker to accept an invitation to dine elsewhere than to offer hospitality himself. His friends argued that he was always in such demand as a dinner companion that he had to share himself around, but his many detractors discerned guile and parsimony. The protracted siege of Lille had extended the campaign season well beyond its usual limit and it was not until the subsequent fall of Ghent in the first week of January 1709 that hostilities were finally suspended. His coalition army was at last able to retire into winter quarters and try to keep up its spirits in the atrocious weather conditions. Unable to sail back to England, Marlborough contrived to get himself invited to stay in The Hague at the commodious home of an obliging Dutch general. When they saw him and his entourage take over half the entire house at no expense, critics said it was one more example of his stinginess, while others countered that he could hardly refuse such a generous offer and – rather than offend his host – had therefore accepted out of sheer politeness. At all events, it meant that the captain-general of the Allied army spent January in the Dutch capital, enjoying a warmth and comfort denied to the vast majority of his men.

Marlborough was not, however, idle. His day started early and he crammed a great deal into it – writing dozens of letters, planning the next campaign season, meeting with senior members of the Dutch army, wooing his other allies and maintaining a busy social life. Adam Cardonnel, his loyal and conscientious secretary, was usually at his side to assist, advise, console or congratulate. In the course of the long and arduous war, they’d been through so much together that they’d been drawn close. Their interdependence was complete. They were seated at a table littered with reports, maps and accumulated correspondence. Finishing a letter, Marlborough read it through before signing his name with a flourish. He pushed the missive aside with a long sigh.

‘It was a waste of time writing that,’ he said. ‘It can’t be sent in this weather.’

Cardonnel looked up from the document he was reading. ‘Is it another appeal to Her Majesty?’

‘Yes, Adam, and it’s doomed to failure.’

‘Not necessarily.’

‘It is. The chances of my dear wife being clasped to the royal bosom again are extremely faint. She pestered Her Majesty to the point where she became intolerable. I’d never dare to say this to her, of course,’ he admitted, ‘but Sarah is largely to blame. She seems to forget that the Queen is recently widowed and still mourning her husband. Limited as the poor fellow undoubtedly was, she doted on Prince George. It’s a time for tact and sensitivity, qualities with which my wife, alas, is not overly endowed. Had she not continued to browbeat the Queen, the rift in the lute wouldn’t have widened beyond repair.’

‘Her Majesty may yet relent.’

Marlborough shook his head. ‘Too many of our enemies have the royal ear. My own position at home is fragile and my wife’s antics hardly improve it. You see my dilemma, Adam?’ he asked, face clouding with concern. ‘If I’m deprived of the support of Her Majesty, how can I retain my position as the leader of the Grand Alliance?’

‘It’s surely not in any danger,’ said Cardonnel, earnestly. ‘One only has to look at your achievements in last year’s campaign. Oudenarde was a triumph that rocked the French to their foundations and it will take them an age to recover from the battle. You then took the prized citadel of Lille before bringing Ghent to its knees. It was one victory after another.’

‘Then why do I feel so insecure?’

‘Only you can answer that, Your Grace.’

Marlborough sighed again. He remained a handsome, distinguished and imposing man but, as he neared the age of sixty, there were clear signs of ageing. His face was more lined, his eyes had lost their sparkle and his back no longer had its ramrod straightness. Seen in repose, he seemed utterly to lack the energy and determination for which he was famed.

‘If only Sidney Godolphin were not so unwell,’ he resumed, ruefully, ‘I’d have more hope. He could continue to solicit support for us. As it is, his position as Lord Treasurer is in question. Lose him and we lose our best ally.’

‘I still say that you should have no qualms,’ encouraged Cardonnel. ‘Your very name strikes terror into the hearts of the French. It would be madness to relieve you of your duties.’

Marlborough fell silent. Overworked and under strain, troubled by migraines, frustrated at being confined to the Continent and sensing the impending loss of his authority, he was in a dark mood. As he turned over the possibilities in his mind, one soon assumed prominence. It allowed him to sound more positive.

‘Perhaps I should petition Her Majesty,’ he said, thinking it through.

‘You’ve just done that very thing, Your Grace.’

‘I talk not of my wife, Adam. This would be on my own account. What if I were to request that I be appointed captain-general for life?’

‘It’s no more than you deserve.’

‘Indeed, it is not. Hampered by the problems of leading a coalition army, I’ve nevertheless delivered three resounding victories on the battlefield and driven the French out of city after city. Such success should be recognised.’

Cardonnel grinned. ‘You don’t have to persuade me of that.’

‘Can I persuade Her Majesty, I wonder?’

‘There’s certainly no harm in trying, Your Grace.’

Marlborough lapsed into silence again, dogged by anxieties about the wisdom of making such a suggestion to Queen Anne. When he won his remarkable victory at Blenheim, he’d been feted at home and granted a sumptuous new palace as his reward. Things were very different now. Over four years had passed and the Queen had become increasingly impatient with a war that was draining the nation’s coffers and liberally spilling the blood of its soldiers. Given the situation, she might not be susceptible to an approach from Marlborough. It might be better to bide his time.

He turned to another cause of vexation. Covert peace negotiations were taking place and, to his chagrin, Marlborough was not directly involved in them. The thought that major decisions might be made over which he had no control was unnerving.

‘What have we heard from the States General?’ he asked.

‘Very little,’ replied Cardonnel. ‘These are early days.’

Marlborough clicked his tongue. ‘Dutch politicians move even slower than those parliamentary snails back in London.’

‘It will take months before negotiations either founder or come to fruition.’

‘If only we knew what that old fox, King Louis, is really thinking.’

‘Well,’ said the other, ‘if he has any sense, he’ll be guided by an incontrovertible fact – namely, that the Duke of Marlborough is invincible.’

‘I don’t feel invincible at the moment, Adam,’ confessed Marlborough, wearily. ‘I feel tired and uneasy. I feel as if everything is slipping away from me and I’m powerless to stop it from doing so.’ He slapped the table with a peevish hand. ‘I want to know exactly what’s going on.’

‘Then you’ll have to wait until word comes from Paris,’ said Cardonnel.

‘If it comes,’ corrected Marlborough.

‘Have no fears on that score, Your Grace. We sent the ideal man.’

‘Remind me who it is.’

‘It’s someone well versed in the art of working behind enemy lines.’ Cardonnel smiled reassuringly. ‘Captain Rawson won’t let us down.’

It was not the first time that Daniel had been to the bakery and he knew how to make himself useful, responding quickly to orders from Flynn and putting the previous night’s escapade temporarily out of his mind. He had learnt how to get the loaves out of the oven without burning his hands and, like his friend, he relished the odour of freshly baked bread. As a reward for his services, he was allowed to taste it. All that he’d told Flynn was that he’d got involved in an argument with two men and had lost his horse in the process. There’d been a long trudge across Paris in the dark and he’d arrived back at the house too late to rouse them from their slumber. Accordingly, he made a bed of straw on the cart and covered himself with a pile of sacks. It was only at the end of the working day that Flynn was able to press for details. They sat side by side on the cart as it rattled homewards.

‘What really happened last night?’ asked Flynn.

‘I told you, Ronan – two men picked a fight with me.’

‘Now why should they do that?’

‘For some reason,’ said Daniel, ‘they didn’t like the look of me.’

Flynn turned to him. ‘I’m not sure that I like the look of you at the moment. You need a shave and your face is covered in flour. Louise will be scared stiff when she sees you.’

‘Your daughter takes after you, Ronan. Nothing frightens her.’

‘Coming back to these two men, who exactly were they?’

Daniel shrugged. ‘I have no idea.’

It wasn’t true. Since the men had followed the courier all the way from Versailles, Daniel knew that they had to be government agents of some sort. As a result, the report of their deaths would be taken very seriously. A hunt would be launched for their killer, based on the description of Daniel given by the nightwatchman who’d held the lantern to his face. Anyone trying to leave the city would come under intense scrutiny. Daniel didn’t want to take the risk of trying to bluff his way past sentries. Yet it was vital that the package was taken to The Hague as swiftly as possible and handed over to Marlborough. It contained information from the very heart of the French government.

‘Do you know what I think, Dan Rawson?’ asked Flynn.

‘What?’

‘I think you’re a dirty, rotten, two-faced, lying bastard.’

Daniel grinned. ‘I take that as a compliment.’

‘Why on earth I bother with you, I really don’t know.’

‘Yet you gave me such a cordial welcome.’

‘That was a mistake. You’re always bad news. Charlotte keeps asking me what you’re doing here – and don’t try to palm me off with that nonsense about bringing a doll for Louise. I’m not stupid enough to believe that.’

‘How much do you want to know?’

Flynn pondered. ‘Nothing,’ he said at length. ‘It’s safer that way.’

‘I’d never put you or your family in any danger,’ said Daniel.

‘You’d answer to me if you did.’ The Irishman flicked the reins to get more speed out of the horse. ‘What happens next?’

‘I need your help to get out of Paris.’

‘What’s to stop you going out the same way you came in? I assume that you have a forged passport of some kind.’

‘It might not do the trick a second time,’ admitted Daniel.

Flynn shot him a glance. ‘In other words, they’re looking for you.’

‘Let’s just say that I need an alternative means of departure.’

‘And why should I help to provide it?’

‘You’re under no obligation to do so, Ronan.’

‘You’re damn right I’m not,’ said Flynn, moodily. ‘There might have been a time when we were birds of a feather but that’s no longer the case. I mean, taking all things into consideration, we’ve nothing at all in common.’

‘I wouldn’t say that.’

‘Look at the facts, man. You’re a soldier and I’m a civilian. You’re a Protestant and I’m a Catholic. You’re English and I’m Irish.’

‘I’m half Dutch,’ Daniel reminded him.

‘Dutch or English – what does it matter? Both nations are fighting to defeat France and I’ve chosen to live out the rest of my life here. By rights, we should be mortal enemies. In fact, I don’t know why I’m wasting my breath talking to you.’

‘It’s because we’re two of a kind,’ argued Daniel.

‘Not anymore.’

‘At heart, we’re both adventurers, men who like to take chances.’

‘You can’t take chances when you have a wife and child, Dan.’

‘Perhaps not,’ said Daniel, ‘but you can yearn to do it. You can still have that urge deep inside you even if you’ve learnt to control it. I simply don’t believe that the Ronan Flynn I once knew has disappeared entirely.’

‘Well, I have. I’ve been reborn as a decent, law-abiding, God-fearing human being who doesn’t want any trouble.’

‘Does that mean you refuse to help me?’

‘Give me one good reason why I should,’ challenged Flynn.

Their eyes locked and Daniel could see that his friend was serious. It was an awkward moment. Without assistance from his friend, Daniel would find it difficult to slip out of the city unseen. He was relying on Flynn to provide unquestioning help.

‘Go on,’ pressed the Irishman, ‘give me one.’

‘Very well,’ said Daniel with a disarming smile. ‘I offer you one very good reason. It’s the only way you’ll get rid of me.’

Flynn burst out laughing. ‘You crafty devil – you’ve got an answer for everything, you silver-tongued son of a bitch. As a patriotic French citizen, I ought to turn you over to the police right now and have done with you.’

‘But you’re not going to do that, are you?’

‘No,’ said Flynn, putting a companionable arm around his shoulders, ‘I’m just dying to see the back of you. For that reason, I’m going to get you out of Paris even if I have to throw you over the city wall with my bare hands.’

Daniel chuckled. ‘I had something a little easier in mind.’

CHAPTER THREE

Amsterdam had not escaped the protracted cold spell. Its streets were frostbitten, its canals frozen and ice floated in its harbour. Holland was a maritime nation that relied on the free movement of its merchant fleet. At the moment, however, its ports were more or less paralysed. Fortunately, a prudent Dutch government had built up large reserves of corn, so the general suffering was not as great as in some countries. Yet it was still a testing time for the inhabitants of Amsterdam. The combination of glacial weather and a shortage of certain foodstuffs lowered the morale of the beleaguered city. Most people chose to stay indoors beside a fire and moan about their lot. What set the Janssen household apart from the majority was the fact that it reverberated to the sound of laughter and applause.

‘It’s magnificent, Father,’ said Amalia, clapping her hands.

‘More to the point,’ observed Emanuel Janssen, ‘it’s finally finished. I’ve spent so much time on the Battle of Ramillies, I feel as if I fought in it.’

‘It’s a masterpiece.’

‘Thank you, Amalia.’

‘What do you think, Beatrix?’

‘It’s wonderful,’ said the plump servant, staring open-mouthed at the tapestry. ‘I hate the thought of battles but this one is different.’

The other servants agreed with nods and muttered approbation. What they were looking at in the extensive workshop at the rear of the house was the completed tapestry commissioned by the Duke of Marlborough and due to hang in Blenheim Palace. Now that its separate elements had been sewn expertly together, it covered one entire wall and spilt over onto the two adjacent ones. It was held in place by Janssen, Kees Dopff and the other assistants who’d toiled at their looms to produce the vivid pictorial record of an Allied victory against the French. Amalia was especially thrilled with the result because Daniel Rawson, who’d taken an active part on the battlefield at Ramillies, had been deputed to advise her father about details of the encounter. It was thus a joint effort by the two people she loved most.

There was, however, a potential drawback.

‘Does this mean that we have to go to England in person to deliver it?’ asked Amalia, warily. ‘I sincerely hope that we don’t.’

‘Transport arrangements haven’t yet been made,’ said her father, ‘and there’s no chance of the tapestry leaving Amsterdam until the weather improves. Whatever happens, Amalia, I promise you that you’ll be spared the journey.’

‘That’s a relief.’

‘I can’t say that I’m looking forward to it. On the other hand, I can’t resist the pleasure of seeing my work hanging at Blenheim Palace. It’s a signal honour. However – under the circumstances – it’s perhaps better if I go on my own.’

Amalia was grateful. As the men began to fold up the tapestry with great care, she turned away and thought about her ill-fated visit to England the previous year. What could have been an exhilarating event in her life had been marred by the Duchess of Marlborough’s curt manner towards them and by the attentions of their host who had stalked Amalia relentlessly. Determined to seduce her, he’d tried to persuade her that Daniel had been killed in action and, to make sure her beloved was no longer an obstacle, dispatched an assassin to kill him. Though Daniel survived and was able to come to her rescue, Amalia’s view of England had been fatally jaundiced. The country held too many painful memories to lure her back.

It was the same for Beatrix Udderzook who’d accompanied her to England.

‘I wouldn’t go there again for all the money in the world,’ she said, stoutly. ‘The only thing I enjoyed seeing was St Paul’s Cathedral.’

‘Yes, that was truly amazing,’ conceded Amalia.

‘I didn’t like their food and I didn’t like the way they treated us.’

‘Then let’s put it out of our mind, shall we?’

‘We have everything we need right here in Amsterdam.’

‘You’re quite right, Beatrix.’

The servant’s eyes twinkled. ‘I usually am.’

Beatrix waddled off to continue her work, leaving Amalia standing beside her father, a round-shouldered man with a silver mane and beard. There was an air of fatigue about him as he looked down at the tapestry, now neatly folded up.

‘It may be the last of its kind,’ he said, sorrowfully.

‘What do you mean, Father?’

‘I’m not sure that I could attempt anything on that scale again, Amalia. My eyes are not what they were and a day at the loom leaves me more and more tired. In future, I’ll have to take on commissions for smaller tapestries.’

‘You should let Kees and the others do most of the work.’

‘If I did that,’ he complained, ‘then, strictly speaking, it wouldn’t be a genuine Emanuel Janssen tapestry.’ He injected a note of pride into his voice. ‘People have come to appreciate my distinctive touch. Anything that leaves this workshop must have that. I’ll continue for as long as I can but at a slower pace.’

‘I think that’s very wise.’

‘It’s a necessity, Amalia.’

‘I know.’ She was struck by a thought. ‘What a pity it would be if you were offered the chance of making another tapestry for Blenheim Palace and had to turn the offer down.’

‘Oh, I doubt that His Grace would approach me again.’

‘He will when he sees the miracles you’ve worked with the Battle of Ramillies. He might ask you to do the same for Oudenarde.’ Amalia’s face glowed. ‘That would be such a treat for me.’

‘Why is that?’

‘Why else?’ she replied. ‘You’d need to speak to someone who fought in the battle and that means Daniel would be appointed as your advisor again. I’d get to see much more of him.’

Janssen smiled. ‘I don’t weave tapestries solely for your benefit, Amalia.’

‘Well, you ought to,’ she teased.

‘Besides, I suspect that Captain Rawson has far more important things to do than describing to me what happened at a battle last year. He’ll be too busy thinking about fighting against the French this year.’ He turned to her. ‘Do you happen to know where he is at the moment?’

Amalia shook her head. ‘No, Father,’ she said, sadly, ‘I’m afraid that I don’t. The army has gone into winter quarters but the war continues in other ways. Daniel could be anywhere.’

Ronan Flynn’s working day started much earlier than that of most Parisians but it finished sooner as a result. There was still a glimmer of light in the sky when he left the bakery with Daniel and drove back home. Having stayed another night with his friend, Daniel had worked hard baking bread in gratitude for the help that the Irishman was about to give him. There were limits to what he could ask Flynn to do and, at all costs, he had to keep his intentions hidden from Charlotte. She was a patriotic Frenchwoman and would not knowingly assist an enemy soldier. As far as she was concerned, he was simply an old comrade of her husband’s and, as such, would always be welcome. Also, she was very fond of Daniel because he’d been so kind and obliging during his previous stay with them. When she agreed to go on a visit to a relative that evening, therefore, Charlotte had no idea that she’d be simultaneously aiding the escape of a British spy.

‘What’s it like out there, Ronan?’ she asked.

‘You won’t notice the cold if you wrap up warmly enough,’ said her husband. ‘It will do you and Louise good to get out of the house for a while. You’ve been cooped up here far too long.’

‘Is Daniel coming with us?’

‘We’ll take him as far as the city gate, my love. Delightful as your aunt is, I don’t think that Dan would want to meet her. It’s a family occasion. He’d only feel in the way.’

‘What happened to his horse?’