Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

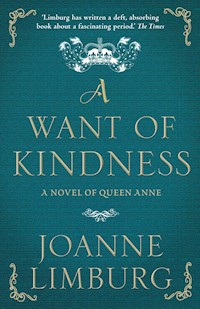

Longlisted for the Historical Writers Association debut novel award 2016. Every time I see the King and the Queen, I am reminded of what it is I have done, and then I am afraid, I am beyond all expression afraid. The wicked, bawdy Restoration court is no place for a child princess. Ten-year-old Anne cuts an odd figure: a sickly child, she is drawn towards improper pursuits. Cards, sweetmeats, scandal and gossip with her Ladies of the Bedchamber figure large in her life. But as King Charles's niece, Anne is also a political pawn, who will be forced to play her part in the troubled Stuart dynasty. As Anne grows to maturity, she is transformed from overlooked Princess to the heiress of England. Forced to overcome grief for her lost children, the political manoeuvrings of her sister and her closest friends and her own betrayal of her father, she becomes one of the most complex and fascinating figures of English history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 554

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A Want of Kindness

Contents page

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2015 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Joanne Limburg, 2015

The moral right of Joanne Limburg to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78239 585 0

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 588 1

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 589 8

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Dedication

In memory of

Ruth Helen Limburg

Contents

Dramatis Personae

Part I

Calisto and Nyphe

The King’s Dogs

Man or Tree?

The Ruin of Winifred Wells

A Catechism

In the Ruelle

What a Good English Princess Knows About Catholics

Love

From Lady Anne of York to Mrs Mary Cornwallis

The Duke’s Dogs

From Lady Anne of York to Mrs Mary Cornwallis

Mary’s Closet

Tom Thumb, his Life and Death

The Dean of the Chapels Royal

Letters From Lady Anne of York to Mary Cornwallis, August 1676 – October 1677

Anne in Flames

Anne’s Skin

Part II

Anne’s Maternal Line

Anne Enters Into Her Closet

The Princess of Orange

The Duchess’s Secretary

The Martyrdom of Charles I

Anne and Isabella

The English Tongue, Already so Rich in Insults, Acquires Two More

Anne in her Closet, Windsor, July, 1679

At The Inn for Exiled Princes

A Game of Ombre

Anne is Thankful

The Duchess’s Ball

Isabella’s Sister

Prince George Ludwig of Hanover

Anne Enters Into Her Cabin

Scottish Gallants

With the Duchess

What Anne Learns from Sarah Churchill

The Duchess’s Health

Lady Peterborough’s Nephew

What a Good English Princess Knows about Protestant Dissenters

The Princess and the Poet: a Romance or All-pride and Naughty Nan: a Comedy

Part III

His Majesty’s Declaration to all His Loving Subjects

The Prince and Princess of Denmark

Anne’s Maids of Honour

Hans in Kelder

Anne’s Fall

12th May 1684

Anne Gives Thanks in Tunbridge Wells

The King’s Body, and his Immortal Soul

King James II’s First Speech to His Privy Council, As It Was Taken Down by Heneage Finch, Printed at London by the Assigns of John Bill, Deceased, and by Henry Hills and Thomas Newcomb, and Subsequently Read to the Princess of Denmark by Her Ladyship, the Countess of Clarendon.

Anne’s Religion

The King and his Parliament

Anne’s Daughter

King Monmouth

Physic

The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes

Anne’s Uncle Rochester

The Triumph of Squinting Betty

The Man from Versailles

The Vapours

The Queen of Hungary’s Water

Anne Treats Her Father Like a Turk

Lady Churchill’s Character

The Man from The Hague

From the Princess of Denmark to the Princess of Orange

Anne’s Fear

22nd October 1687

The Queen Is With Child

The King’s Vexation

The Queen’s Belly

From the Princess of Denmark to the Princess of Orange

16 April 1688

Exodus 14:13

From the Princess of Denmark to the Princess of Orange

The Parable of the Ten Virgins

Anne’s Uncle Clarendon

His Majesty Bleeds at the Nose

Part IV

The Throne is Vacant

Anne’s Abdication

Anne’s Sister

Lord Devonshire’s Leavings

Peas

Anne is Delivered in State

Mrs Pack

Persons Not At Ease

Anne in Lent

Chintz

Campden House

14th October 1690

The Queen’s Ladies

Anne Dines at Holywell

Anne’s Non-Naturals

The Reformation of Manners

From the Princess of Denmark to King James, written with the assistance of the Earl and Countess of Marlborough

Anne and her Sister Mary

The Earl of Marlborough’s Dismissal

From the Queen to the Princess of Denmark

From the Princess of Denmark to the Queen

Syon House

17th April 1692

Unkindness

Lady Marlborough’s Misfortunes

The Duke of Gloucester’s Birthday

Anne is Pardoned

In Bed with the Denmarks

What a Good English Prince Knows About Warfare

21st January 1694

Gloucester’s Progress or The Making of a Soldier

Mary Consumed

Part V

Anne at Thirty

The Good Hope

20th September 1696

Anne Dances

Love for Love

25th March 1697

The Peace of Ryswick

2nd December 1697

Whitehall Burns

Gloucester Is Taken Out of the Hands of Women

15th September 1698

Anne’s Bedchamber Woman

25th January 1700

From the Princess of Denmark to the Countess of Marlborough, in gratitude for her Lord’s good offices in securing a repayment for the Prince

The Duke’s Eleventh Birthday

Settlement

Acknowledgements

Dramatis Personae

Part I

Calisto and Nyphe

Anne and her sister Mary make their entrance into Court under wooden clouds, that smell a little of distemper. Their bodies are draped in heavy layers of silk and brocade, run through with gold and silver thread, and made heavier still by the many jewels their dressers have attached to them; Anne feels heavy inside too, as if all the months of practice and expectation, the dancing lessons, the acting lessons, the fittings, the conversations overheard, and even her own prayers have all been mixed up and baked together, so that now the whole concoction sits stolidly in her breast, like a pudding on a pantry shelf.

For all this weight, she treads daintily – if not quite as daintily as Mary – her arms outstretched as they have been taught, holding a castanet in each hand. The sisters take their places first, then the other young ladies take their places behind and to either side. First they curtsy – everything begins with a curtsy – then there is a little pause, a quick burst of applause, and the music starts, half flowing up from the pit, and half down from the clouds, two separate streams of sound that pool together on the stage, exactly where she stands.

Now they begin to trace the steps that they have learned, with the viols and the recorders treading alongside, three slow beats at a time; underneath the music, Anne can hear the heels of their shoes sliding against the baize, the little thuds they make when they all step in time, and the rustling of their skirts whenever, with a pert clicking of castanets, they kick up and show the Court their stockings. It is a pretty song, so the hardest task she has is to keep herself from humming. The Court is watching her, so the Court might well be listening too.

Anne is, for once, grateful that God has given her such bad eyes. From the stage, the Court is no more than a glistening murmur, held at bay by a row of candles. Their flames run together, making a bank of fire. She can see smaller lights flashing on the dancers’ costumes and when the dance brings her close enough, she catches a glimpse of a face: Mary’s is taut with concentration; the others’ are scared or excited or saucy, according to temperament. This is as much as she wishes to see. If she saw anything more, she fears she would not be able to dance at all.

The music stops, the Court applauds, and now Anne can go back to the tiring-room, where Danvers and the other dressers are waiting, and where she can refresh herself from dishes of oranges, olives and almonds. As she steps through the wings, she meets the Duke of Monmouth and his gentlemen on their way to the baize to dance a minuet. Lady Henrietta Wentworth stops suddenly to watch them walking out, and Carey Fraser, who is just behind, nearly trips over her gown – a couple of the other young ladies giggle, and are shushed.

Monmouth is the King’s eldest son, but not his heir: that is the King’s brother, the Duke of York, Anne’s father. Mary’s and Anne’s places, at Court, and in the succession, are therefore ordained by God, and the masque they are about to perform has been commissioned so that these important truths might be confirmed and demonstrated. Monmouth’s place is altogether less certain, but he is handsome and beloved, one of the lights of the Court, so it is only right that he should have his minuet, and lead the dance. Mary says it is to show the world how well the King loves him; Squinting Betty Villiers, who has no part, says it is to show the Court how well his leg is turned.

The masque has been written by a Mr Crowne who, as he writes in his dedication to Mary, has been unexpectedly called out of his obscurity by the command of their step-mother the Duchess, to the glory of serving her fair and excellent Highness. So unexpected was this call, he explains, that he has not had time to ripen his conceptions, and regrets that the words he has found for Mary to say must fall sadly short of the excellence of her thoughts:

For none can have Angelical thoughts but they who have Angelical virtues; and none do, or ever did, in so much youth, come to so near the perfection of Angels as yourself, and your young Princely Sister, in whom all those excellencies shine, which the best of us can but rudely paint.

Anne is used to hearing Mary’s perfections praised: she is quick, she is diligent, beautiful, agreeable, pious; she dances gracefully, draws and paints exquisitely, embroiders charmingly. Conscientious in all things, she read the whole libretto of Calisto: the Chaste Nymph as soon as it was put into her hands. Her young Princely Sister has seen only her own parts, because reading makes her eyes water. Mary’s view is that Anne could read much more if she wanted to, but as she is herself always just as willing to talk as to read, she has told Anne the whole story, more than once:

‘We’re to play sisters – Calisto and Nyphe – they’re princesses, and nymphs serving Diana. Jupiter and Mercury watch them. Jupiter loves Calisto. She loves only innocence and chastity, but there’s a jealous nymph, Psecas, who thinks she’s shamming it. Psecas knows Mercury loves her, and means to pretend to love him in return, so her conduct will shame all the rest—’

‘How’s that?’

‘Because if one nymph loses her honour, it throws suspicion on the others. Where was I . . .? Jupiter tells Mercury how he’ll appear to Calisto in Diana’s shape, thinking that she cannot mind if her mistress caresses her, so he finds Calisto and embraces her and she thinks he’s Diana run mad and calls “Help!”—’

And here Mary strikes the appropriate attitude.

‘—so he shows himself in his true shape, but she still won’t have him, so he orders the Winds to seize her. Then his jealous Queen, Juno, comes looking for him. In the meantime, Mercury promises to make Psecas a goddess, and they plan to have Calisto shamed, and Nyphe too. Nyphe finds them and – listen, Anne, this is your biggest part – she quarrels with Psecas, who thinks herself above the others now—’

‘And I tell her that I am a princess born, but she is only made great by her lover.’

‘So you have read that, at least – yes, and then Psecas and Mercury plot to show Nyphe with Mercury and Calisto with Jupiter in front of Diana and Juno. Then Juno finds Jupiter and Calisto, and Jupiter tells her he’s to have Calisto as well as her. Then Nyphe finds Calisto alone, and they weep together.’

‘But then . . .?’

‘Then Mercury finds Psecas and tells how he’s roused Juno to punish Calisto, and now they will shame Nyphe. Now the sisters are enchanted and afraid. They see Diana and— no, there’s something else: Juno appears and tells Diana she is deceived in Calisto, and— Sister, you do not listen—’

‘I am. I do. Mary, do please go on.’

‘Very well. So now . . . so now the sisters come. They think Diana is Jupiter so they strike her with darts, so Diana says they must die. Then Juno says she’ll crown Psecas a goddess, but Psecas makes Mercury angry, so he tells all to Diana, and so the sisters’ honour is restored. Psecas is banished, and Jupiter sets the sisters in the sky to rule over a star. And that’s the end.’

If Mary has told this story more than once, it is because Anne has asked more than once, partly because she is reassured by repetition, but also because the story seems to complicate itself further with every telling. By this time, though, she has grasped the chief point, which is that nobody much cares if she understands, as long as she speaks her lines beautifully, and as she is well able to do this – Mrs Betterton has even commended her voice to the King for its sweetness – she is no longer troubling herself, or Mary, about the intricacies of the plot. After all, Mary is thirteen and it is quite natural that she should comprehend more than Anne, who has only just turned ten.

Anne understands this much: the play is about lovemaking, adultery and attempted ravishment, but it is from the Classics, and all the parts are taken by ladies, so there can be nothing improper in it. The gods Jupiter and Mercury are played, respectively, by Lady Henrietta and Sarah Jennings, while their father the Duke has commanded Margaret Blagge out of retirement from Court to play Diana, and Anne has heard from several reliable sources that Mrs Blagge is so given over to goodness and piety that she has sworn never to say or do one amusing thing ever again. Margaret is sharing a tiring-room with the princesses and other principals, and while they wait between acts she sits on a chair in the corner, reading a book of devotions. When they are called for the first act she puts down the book with conspicuous reluctance, accepts her bow and arrows from her dresser, and takes her place at the head of her train. Mary follows her, then Anne, and then Lady Mary Mordaunt, who is Psecas. A group of lesser ladies, playing lesser nymphs, join them in the wings, and they complete the retinue.

Anne hears Jupiter’s last lines –

She swiftly by like some bright meteor shot

Dazzled my eye, and straight she disappeared

– and thinks, as she always does, of Mrs Jennings, who leaves the stage as they come on, bright-haired and dashing in her breeches, her smile like a private letter.

After a long evening of pursuing and plotting, resisting and weeping, denunciations and revelations, all interspersed with the affairs of shepherds and shepherdesses from the King’s music, and dances of Basques, Cupids, Winds, Satyrs, Bacchuses and, finally, Africans, the sisters make their final entrance under a great canopy, with the Africans supporting it.

Jupiter is to crown them before an assembly of all the gods, so as soon as they reach centre stage, the wings are pulled back, and behind and above them a heaven is revealed in the form of a glory, with the gods and goddesses seated in front of it. The glory is made of a huge back piece with a round hole in the middle of it, taffeta stretched over the hole and many dozens of candles behind. Anne can see nothing of this, but she can feel the heat, which, added to the warmth of the footlights, her heavy costume and the press of bodies on stage for the finale, is suddenly almost too much. But soon enough Lady Henrietta has descended from the glory to speak the epilogue, and it is nearly over.

Jupiter announces a final change of heart: he will not waste their virtue and beauty on a star. That is no way for a king to dispose of princesses: he will keep them to oblige other thrones, to grace some favourite crowns. Having spoken, Lady Henrietta steps forward in her own person and addresses the real King, on the subject of the real princesses:

Two glorious nymphs of your own godlike line,

Whose morning rays, like noontide, strike and shine

Whom you to suppliant monarchs shall dispose,

To bind your friends, and to disarm your foes.

The King’s Dogs

The tiring-room is suddenly full of dogs, excitable little spaniels; for formality’s sake, a footman announces that the King is coming. All the goings-on in the room, the eating and drinking, flirting and gossiping, jokes and congratulations, stop in an instant; for a moment there is nothing to hear but panting and snuffling on one side of the doorway, and well-shod feet approaching from the other. Then Anne’s uncle is at the door, and the room lowers itself, bending at the waist and the knee.

The men on either side of him have kept their heads covered, so must be ambassadors, here to examine Mary. The usual pack of courtiers follow the three of them as they approach her, and she greets them all with a perfect curtsy, first taking a step to one side, towards the men, then drawing the foot back so that her heels touch, before making a bend of carefully judged depth, allowing her arms to fall gracefully to her sides. All the men, apart from the King, bow in return, the ambassadors slightly, the courtiers deeply and elaborately.

The King lifts Mary’s face by the chin, holds on to it while he praises her dancing, her poise, her height, her fine verse-speaking, her charming yet modest demeanour and, most fulsomely, her beauty. The ambassadors join in with accented compliments. Meanwhile, Anne’s favourite spaniel, Hortense, starts sniffing about her skirts, so she bends down to pet her. They are both of them afflicted with a constant watering of the eyes, and Anne believes that this has given them a special understanding.

She is stroking Hortense’s ears when a hissed Your Highness! from somewhere makes her jump: the King has finished with Mary and is now addressing her. As she straightens up, she feels one of her worst blushes coming, hot and red, spreading out from the sides of her nose all the way to her ears, up to her temples, and down to her neck. Once the blush has started, nothing can go right, and her curtsy is sufficiently unlike Mary’s for some of the courtiers to laugh a little into their sleeves. The King, at least, doesn’t laugh. She looks straight up at him, at his black intelligent fox face, and waits to hear what he has for her.

‘Anne, I think you astonished our Court tonight.’

She sees she is expected to speak.

‘How is that, Your Majesty?’

‘With your voice. We hear it so seldom, and that is a great pity, for it is a very fine thing, sweet and clear. If you were not a princess, you should have a great career upon the stage. It was a pleasure for us to hear you speak your lines – a great pleasure. We must work upon that voice – I shall have Mrs Barry give you more lessons.’

‘Thank you, Sir.’

‘But tell me . . .’ and he leans towards her, ‘which shall you be, do you think? A comedienne or a tragedienne, hmm?’

Anne knows that she should provide an answer, but she has nothing to offer except more blushes. All the same an answer comes:

‘Her Highness is too modest to give an answer, for the truth is that she knows she must excel at both.’

But it isn’t her voice – it is an older, altogether more confident one, and it comes from behind her, from the same source as the hiss: insolent Mercury, speaking out of turn.

Her uncle’s gaze shifts, and a change comes over him, so that he reminds Anne of the way Hortense looks when she thinks she might have caught the scent of something interesting.

‘Vivacious Mercury,’ and he beckons Sarah Jennings forward. She makes her curtsy a little awkwardly, because she is still in breeches, but a sound performance, all the same.

‘So, Mercury, what will you?’

‘I, Your Majesty?’

‘Yes. The Lady Anne is for the stage, but Mercury?’

Sarah gives the King, the ambassadors and Court gentlemen only the shortest time to watch her thinking before she replies:

‘Well, Sir. When Mercury has put off his costume he must become Mrs Sarah Jennings again, a most dutiful Maid of Honour to her Grace of York, and later, if it pleases God, some gentleman’s virtuous wife.’

There is a brief silence in which many things Anne does not understand seem to be happening, and then her uncle bursts into laughter, taking his pack of gentlemen with him.

After the King has left, Anne asks Sarah why he laughed. Was it because she was jesting?

‘No,’ Sarah replies. ‘He laughed because I was in earnest.’ Then she lowers her voice and adds: ‘Your Highness, try not to screw your eyes up so: people are saying it gives you a disagreeable look.’

Anne’s Eyes

For as long as Anne can remember, her eyes have caused consternation. It is on account of them and their watering that her earliest memories are all in French.

She is at her grandmother’s chateau in Colombes, and one of her grandmother’s physicians is dropping something into her eyes. She cries, then her face is wiped, and she is given something to eat. Later, in the nursery, something nasty is spooned into her mouth; she splutters, and cries again, and is given something nicer to console her.

Her grandmother falls ill and takes to her chamber; then she disappears altogether and Anne is taken to another nursery. It belongs to her cousin Marie Louise, who is sometimes kind to her and sometimes a tormentor. Every now and then their play is interrupted for visits from Marie Louise’s mother – the kind and pretty aunt whom everyone calls Madame – or from more physicians who come to put drops in her eyes. Sometimes they cut or blister her for good measure. The doctors come and they go, but there are always ladies to wipe her face, to administer nasty spoonfuls, and to feed her sweetmeats afterwards.

Months pass like this, then a day comes when the house is full of people hurrying and hushing and nobody remembers to wipe her eyes. They are all wiping their own, because her aunt Madame is dead. Her uncle, Monsieur, comes to the nursery, puts his hand on her head, and gives her a candied apricot. She does not like Monsieur – maybe it is his smile, or perhaps his smell – so she hides the apricot inside her sleeve and drops it later, in a corner.

On Monsieur’s orders, Marie Louise and Anne are dressed in long violet gowns with veils down to their feet, and she is dragged, stumbling, to a chapel where she is upset by overwhelming music, rich scents and too many adults weeping.

Soon after this, she is told the good news – her father has sent for her, and she is to return to London, because her eyes are cured! She is put on a boat with her ladies, and two pearl and gold bracelets, a present from the King of France. They are such beautiful things that she feels compelled to lick them, but as soon as she does so, they are taken away. And then her eyes are wiped again.

Man or Tree?

That night they stay at their father’s house, at St James’s, but next day they are sent straight back upriver to Richmond, where the air is cleaner, and the smell of rut only perceptible when the deer are in season.

Even in a royal barge, with eight strong oarsmen, the journey takes a couple of hours or more, and the first part, from Whitehall Stairs, is never pleasant. The night before, in the prologue to Calisto, Thames made her appearance as a beautiful river nymph draped in silks, leaning on an urn, attended by Peace, Plenty and the Four Parts of the World, all come to pay homage and bring her presents of sparkling jewels. In daylight, her character is quite different. Her broad body is pasted all over, in the most ramshackle way, with boats of various sizes and states of repair, which are themselves studded haphazardly with boatmen, passengers, coal, timber, livestock, cabbages, pails of milk, and whatever else London and the Court might consume, or excrete. Her attendants, the watermen, hail her with coarse and violent oaths. One small mercy, as Danvers says, is that it is February, and cold, so the smells are not too bad.

But the cold, like the watermen, is no respecter of rank, and it is pretty bad. The princesses are sitting in the shelter of the tilt with their dressers and Sarah Jennings, they are wrapped up in heavy cloaks, fur boas and fur muffs, but the cold comes to find them all the same, to pinch their royal noses. Anne pulls her hood over her face, as far forward as she can. Mrs Danvers asks if she might not push it back just a little, but Anne says ‘No’, and this sets Mary off telling Mrs Jennings her favourite story about her sister. Anne supposes Mrs Jennings must be the only one of their stepmother’s Maids of Honour not to have heard it already.

‘My sister can be so stubborn.’

This is how it always starts.

‘She was quite small then – I remember she had not long returned from France – and we were walking in the Park together, out in the open, and we saw something at a great distance. Whatever it was, it was too far away for us to be certain as to what it was – of course we both have our bad eyes, but even if we did not – but we were wondering aloud together what it was, and then a dispute was started between us as to whether this something were a man, as I believed, or, as my sister thought, a tree. After a short while, we came near enough to make out the something’s shape, and then, clearly, it was a man, so I said, “Now Sister, are you satisfied that it is a man?” But then Anne, after she saw what it was, turned so that she had her back to him, and cried out, like this – “No, Sister, it is a tree!”’

Sarah laughs obligingly, then turns to Anne and asks her, ‘But what were your thoughts?’

Anne pushes her hood back long enough to say, ‘Mary tells everyone about this, but I don’t recall it,’ then having nothing more to add, retracts her head again.

The Ruin of Winifred Wells

Anne has been told, many times, that Richmond was a great Palace once, but that was before Cromwell and his traitorous Parliament took possession and sold it. Then the buyers took down the white stones of the State and privy apartments, the Great Hall and the Chapel, leaving only the red-brick buildings that had housed the lesser people, the courtiers and officials. Now Cromwell’s head sits justly rotting on a spike above Westminster Hall, while the Duke of York’s daughters inhabit these red-brick remains, along with their governess, Lady Frances Villiers, her daughters Betty, Barbara, Anne and Catherine, their chaplains, nurses, footmen, necessary women, laundresses and suchlike, portraits of forgotten courtiers and various pieces of heavy oak furniture no longer wanted at St James’s or at Whitehall, where tastes run to more delicate items, fine-legged, inlaid or japanned, and preferably made of walnut.

So when they sit down to dine, it is at a refectory table of quite exemplary sturdiness, the bulbous legs of which, as Sarah Jennings points out, resemble nothing so much as two rows of squabbish frights in farthingales.

Eating dinner is one activity to which Anne always applies herself most diligently. It is not only that she loves it for itself, but also that nobody can reasonably ask her to speak if she’s using her mouth to eat with. When at table, the sisters always divide the labour between them: Mary keeps up the flow of conversation, while Anne eats.

In this way, they work together through the first course, and the second. Mary chatters, laughing first, then checking herself, then moralising, then forgetting herself, and laughing again. The Villiers sisters, Betty especially, do nothing but laugh. They find Mrs Jennings particularly amusing; Anne cannot help noticing that her sister does not.

With dinner almost over, the broken meats of the second course not yet removed, Anne pulls a silver dish towards her, and helps herself to a sippet. It is her favourite way to end a meal: first she crams the sodden bread into her mouth, then – and this is the heavenly part – she presses it against her palate with her tongue, forcing the warm gravy out over her tongue and down her throat, waiting until the last, tiniest drop has gone before chewing and swallowing the squeezed-out bread. She has finished one and is reaching for her second, when Mary’s brittle voice cuts in:

‘Sister, must you always finish every sippet on the table? I fear you will grow as fat as our mother did.’

The word ‘mother’ to Anne means a richly upholstered lap, and sweet bites offered by sparkling, chubby fingers. Fat or not, the face has long since faded, and she takes the portraits on trust. Now another sippet has arrived in her mouth; she hears her sister huffing through her nose, and glances towards her.

Mary is sitting bolt upright, her face severe, a silver spoon held with conscious delicacy halfway between a bowl of rosewater cream and her perfect mouth. Anne stops, shamed, her mouth full of half-sucked sippet. She can hardly spit it out, but she no longer feels like swallowing. Then Mrs Jennings pushes another dish towards her, saying, ‘But such tiny morsels, what difference can they make?’

‘Besides,’ Betty adds, ‘surely it is the duty of every royal person to increase her dignity?’

‘My sister needs to learn to moderate her appetites.’

‘Quite so,’ says Betty, and then, in a voice a little less like her own and a little more like Mary’s she adds, ‘We might all profit by your example: I have never known Your Highness to sit down more than three hours at the card table, or to write to her dearest dear Mrs Apsley more than twice in one—’

‘That’s enough, Betty.’

‘Yes, Mother. That was too sharp: Madam, forgive me.’

If Betty sounds less than sincere, Mary is gracious enough to accept her apology in the spirit in which it should have been offered. Anne continues with her sippets, and the conversation moves on. Sarah Jennings is asked for her opinion on the Duchess’s other Maids of Honour, which she delivers in plain terms.

‘Great fools, for the most part, and easy prey. There’s hardly one among them who wouldn’t exchange her honour for a pair of kid gloves, a fan or two, a handful of compliments and some inferior verses bought off a hack.’

‘I heard,’ says Barbara, ‘that Monmouth and Mulgrave and even—’ she stops short and looks at Anne, ‘others are daggers drawn over Mrs Kirk.’

‘Mary Kirk is the biggest fool of all of them – and lately most unwell.’

‘That I can believe.’

‘It was just the same when my sister Frances was at Court. Worse, perhaps – have you heard of Winifred Wells?’

‘Winifred Wells?’ Betty sits up. ‘Wasn’t she the one who—’

Sarah, not to be cheated of her story, cuts in again. ‘Had a mind to take Lady Castlemaine’s place with the King. She was pretty enough, but had no wit to speak of, and surrendered far too readily to hold his interest—’

‘There is a verse about her!’ Betty again. ‘It puns upon her name, like this:

“When the King felt the horrible depth of this Well,

Tell me, Progers, cried Charlie, where am I? oh tell!

Had I sought the world’s centre to find—”’

‘Betty! You are quite incorrigible! Remember where you are!’ Sarah takes up the story again. ‘So, the affair did not last, and no-one – except I suppose Mrs Wells – thought much more of it, but then some months later, at a ball, in the very midst of the Court, as she was dancing in Cuckolds All Awry, she suddenly stopped, and groaned, and before everyone’s eyes she dropped her child!’

Anne clears her throat suddenly, and everybody looks at her. ‘What became of the baby?’ ‘Another dancer, a lady, took it up in a handkerchief—’ ‘Did it not cry? Had the dancers stepped on it?’ ‘No, I believe it was . . . it was an abortion, quite dead.’ ‘Just as well, under the circumstances,’ says Barbara. ‘Perhaps, but Mrs Wells had to leave Court, all the same.’ Then Lady Frances announces, very firmly, that dinner is over. Anne is glad of this: she has the beginnings of a stomach ache.

A Catechism

First, Anne believes in God the Father, who hath made her, and all the world.

Second, in God the Son, who hath redeemed her, and all mankind.

Third, in God the Holy Ghost, who sanctifieth her, and all the elect people of God.

Her duty towards God is to believe in him, to fear him, and to love him, with all her heart, with all her mind, with all her soul, and with all her strength; to worship him, to give him thanks, to put her whole trust in him, to call upon him, to honour his holy Name and his Word, and to serve him truly all the days of her life.

She knows that she is not able to do this of herself, because she is weak, and naturally sinful, and so cannot walk in the Commandments of God, or serve him, without his special grace, which she must at all times call for by diligent prayer.

Every morning and every evening, she says the Lord’s Prayer, and asks him to lead her not into temptation.

She prayed last evening, and again this morning, but she cannot deny that her heart and mind were both times very much taken up with the play, the dancing, the costumes, the Court and Mrs Jennings.

So that there was not enough room in them for God.

So when she prayed, he did not hear her; he caused sippets to appear before her at dinner time, and she ate a surfeit of them.

This surfeit being an offence in his eyes, he has sent her a correction in the form of a stomach ache, so there will be no cards after dinner, and no tea.

But as he is merciful, he has also provided a spoonful of Mrs Danvers’ surfeit water, and a soft bed on which she may bear her sickness patiently, and with a contrite heart.

In the Ruelle

Anne is the cunningest fox that ever was. She has made a harbour of the ruelle in one of the bedchambers at St James’s, and her sister and step-mother may seek as much as they like, but they shall not find.

When Anne was smaller, too small to understand that grown people have different pleasures, she supposed that the Palace was built with hide and seek in mind. Behind the well-ordered state rooms is a ravelled heap of closets, staircases and narrow, curving passages that drop down a step without warning, or run on for miles with nothing in them but bottled ships and dead mice, or end abruptly in sullen, doorless walls. Hiding in the ruelle, Anne sits between the two palaces: to her right, behind the hanging, is the Duchess’s Great Bed; on her left is the wall, with a door in it which leads to a closet, which has another door, that leads to a staircase, that might lead to another closet, or the kitchens, or outside, or anywhere.

As far as the game is concerned, it makes no difference where the staircase goes, because neither Mary nor the Duchess will be ascending it to find her. Anne has taken care to put the greatest possible distance between her and her pursuers, and to travel it by the most elaborate route. This is not a stratagem that would ever occur to the other ladies, who are both by nature too obliging to put anybody to the trouble of searching too long or with too much effort. Anne has no such scruples: she likes to know that her absence is felt.

Once she has arranged herself comfortably, and her eyes have accustomed themselves to the darkness, she rummages about under her skirts until she finds her pocket. She has a secret hoard in there, some sugar-plums she had from the housekeeper this morning. It is only after she has popped one into her mouth and broken its shell that she remembers she has given them up for Lent.

Anne had her first proper conversation with her step-mother a couple of months after the new Duchess’s arrival in England. Her English had already improved greatly by then, and she was crying only every other day, so was a good deal more approachable than she had been. She had come to visit Anne and Mary at Richmond, and, although religion was not to be mentioned, they had come, somehow, to be talking of fast days.

‘We had soupe maigre,’ said the Duchess, ‘every fast day the same, and I hated it so much, but my mother said I had to have it, she made me and she watched me and I was not allowed to stop until I finished the bowl.’

Anne, so used to parables and homilies, searched for the moral.

‘But then you found the soup was tolerable after all?’

The Duchess shook her head. ‘No. Never, and every fast day I wept into the soup.’

Anne thought of the Duchess’s mother on her visit, insisting that she must have precedence over all the great English ladies, and seating herself in the Queen’s presence while other duchesses stood. Mary must have been thinking the same, because she remarked that the Duchess Laura was indeed a most commanding person.

‘Commanding, yes. I was scared of the men who cleaned the ashes in my chamber – they had black faces – what do you call them here?’

‘Chimney sweepers.’

‘“Chimney sweepers.” Thank you. They frightened me when they came, and I told my mother, so then she told them to come closer to me: I was of the Este family, and I should not be frightened.’

For a long time, it seemed as if the Duchess was as frightened of the Duke as she had ever been of chimney sweepers, and whenever he came close, she would cry all the harder. Fortunately, however, he fared better with her than fast-day soup: after a while, she came to find him tolerable after all, and a little after that to love him. These days when she cries it is usually because he has been moving in close to some other lady. That said, the Duchess is in excellent spirits today. She has recently come out of her first confinement with a healthy child – a daughter, but never mind – and the Duke, when not out hunting, is most attentive.

Anne becomes aware of busy noises in the closet next door. She wipes her mouth quickly, and straightens her skirts, but when the door opens it is neither Mary nor the Duchess, but only a necessary woman, a very young one, with a fresh chamber pot. Both girls are equally startled; they blush at each other, while the necessary woman hurriedly conceals the chamber pot behind her back. Then she curtsies and mumbles something that might be ‘Your Highness’. They blush together for another moment, then Anne whispers, ‘Pray don’t alarm yourself: it’s only a game. I’m hiding.’

When the necessary woman has completed her return journey, and the renewed blush has died down, Anne is returned to darkness and to quiet. Nobody else comes into the chamber or the closet. She hears the clang of the bell in the clock tower, and begins to wonder if Mary and the Duchess are ever going to come. Perhaps they have given up the game altogether, and have sent one of their ladies to look for her. They might have picked up their work again, or started playing cards. The Duchess’s card-playing has improved along with her English, and nowadays she plays as often as any other lady at Court; she even plays on Sundays, with the Queen. Dr Doughty has made it clear to the princesses that it would not be expedient for them to join her on these occasions: Sunday card-playing is a sin, and more to the point, a Catholic one.

What a Good English Princess Knows About Catholics

They do not belong to God’s Church, but to the Pope’s, and he is the Antichrist, the Son of Perdition, who opposes and exalts himself above all that is called God, and sits in the temple, dealing in signs and lying wonders.

Some you meet may be agreeable, even kind, they may do many good works, but nevertheless they shall not be saved. Salvation is the reward of a life lived in the light of God’s truth, a truth found only in the Bible, which Catholics do not hear. In the English Church, the Bible is read over to the people once every year, and in their mother tongue, so that they might see for themselves the process, order and meaning of the text and therefore profit by it, but in the Popish Church, such scripture as the people hear is broken up and read to them in Latin, which they do not understand; then the Word is further smothered under a multitude of responds, verses and vain repetitions. If any drops of truth remain, they are quenched by the priests and Jesuits, with sophistry and traditions of their own making, founded without all ground of scripture. Such men can take the text and twist it, and do so with such serpentine subtlety, as to amaze the unlearned, and turn plain truth to riddles. By these means and others, the Popish clergy maintain their abominable mischief and idolatories, and damn their people with them. Any Englishman who chooses such a religion, when the truth is plainly laid before him, has declared himself an enemy of that truth. And if he is not a true Christian, then he is not a true Englishman either, for a man can be loyal only to one prince, and the Catholic looks not to his King, but to the Pope in Rome. His design, and that of Popish kings across the Channel, is to bring England under Catholic tyranny, and to this end they have waged ceaseless war against the English, from without, and from within. Queen Elizabeth’s life was often in danger; there was even a plot to kill King James with all his Parliament, which by the grace of God was foiled. Every year the people give thanks for this deliverance, and burn the Pope in effigy, with a cat sewn into his belly to make him scream.

And this was deliverance not only for the King and his Parliament, but for every Englishman, for it is quite certain that under a Catholic prince he would lose his freedom, his religion, his property and the rule of law, and in their stead get persecution, blood and fire. Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, which is nearly as true as the Bible, shows how this happened in the reign of Queen Mary, when anyone who proclaimed God’s word was hunted down, imprisoned, examined, tortured and condemned to die in flames. Anne Askew was so tormented on the rack that she couldn’t walk to her own execution; Lawrence Sanders’ death was drawn out on purpose, because they burned him with green wood, and other smothering fuel, so put him to much more pain. When the bloody Bishop of London had Thomas Tomkins in his custody, and found that neither by imprisonment, nor beating, nor by shaving off his beard could he persuade him to renounce his faith, he became so vexed against the poor man, that he thought to overthrow him by some forefeeling and terror of death. With this in mind, he took Tomkins by the fingers, and held his hand directly over the flame of a candle, but so rapt up was Tomkins’ spirit that he felt no pain, and never shrunk, even when the sinews burst, and the water spurted into Master Harpsfield’s face.

No-one was spared in these terrible times, not even princesses. The Queen’s own sister, the Lady Elizabeth, suffered terrible persecution, which no-one could have borne more bravely. By the Queen’s own orders, she was fetched from her sickbed by a troop of a hundred and fifty horse, put under armed guard, and taken to the Tower, where she was examined, and falsely accused of treason. Then she was imprisoned in Woodstock, still under guard, and in danger from plots to murder her. The Bishop of Winchester even sent a writ for execution while she was there, and it was only by God’s Providence that this came to no effect. All the time she was in captivity, guiltless men were racked in the Tower, in the hopes of persuading them to accuse her, and even when she was let out of prison and went to Hatfield, she was closely watched until her sister’s death.

The story of Lady Elizabeth and her miraculous preservation is the only one in the book that does not end in death, but that is not to say that the others do not have happy endings, because every martyr in it concludes his or her earthly life by praising God even in the midst of the flames, and departing to a better place, there to live in joy unspeakable. In the pictures their faces are rapt and beautiful, their arms raised like a preacher’s in the pulpit, and words of faith come out of their mouths on long ribbons: ‘Welcome lyfe!’ says one; ‘Lord receive my spirit!’ cries another. Every story is beautiful, because it tells that even though there may be persecution and suffering in this life, for those who remain steadfast in their faith there will be a just reward in the next, and for their persecutors, just punishment.

It puzzles Anne very much, knowing all this, that her father should choose to be one of them.

Love

‘I love my love with an A’, says Mrs Jennings, ‘because he is Admirable.’ It is Betty Villiers’turn. ‘You would be better, Mrs Jennings, to love him with a B, seeing as he is Betrothed to another.’ ‘And you with a C,’ says her sister Barbara, ‘because you are Canker-tongued.’ Betty shrieks with laughter. ‘How you cheat, Bab! Canker-tongued! There is no such word!’

Now Sarah declares herself sorry to have ever started the pestilent game, turns her back on the Villiers sisters, who carry on without her, and sits down next to Anne.

It is summer, so the Court has moved to Windsor. The King spends his time fishing, walking, playing tennis and visiting his mistresses in their lodgings, while the Queen holds picnics. Today she and the Duchess have joined their two households together, and there are several dozen women gathered under the shade of the oak trees, ladies and servants seated side by side. Leaves sieve the strong afternoon sunlight, letting through just enough to lend the servants’ plain gowns a few hours of sparkle, while protecting the ladies’ complexions.

Food and drink are shared along with the sunlight, and everyone has brought a dish: there are chines of beef, venison pasties, several dozen ruffs and reeves, baskets of fruit, all kinds of sweetmeat and several cases of wine. Mary is sitting a little way away, with her friend Frances Apsley, picking delicately at the contents of a fruit basket, so Anne has been able to work her way through the heavier dishes unseen and unrebuked.

The Duke’s newest daughter, baby Catherine, has joined them for the meal, and is sitting on her nurse’s lap, mumbling a crust of bread. She has a sticky cascade of saliva running down its bed of crumbs from her lower lip onto the lace of her mantle. A few more crumbs come out every time she smiles, but all the same her smile is beautiful, and Anne has a most excellent way to bring it out. If she sounds one pair of strings on her guitar, the corners of Catherine’s mouth will begin to turn up; if she thrums all the strings at once, then the baby smile will break out in its full glory. Pushing the experiment a little further, she plays the first few notes of the chaconne that Signor Corbetta has been teaching her this last week, and now the baby is more delighted than ever, crowing and waving her newly unswaddled arms about until the crust flies out of her hand.

Sarah Jennings rushes to pick it up, but Mary Cornwallis gets there first. She is the York sisters’ oldest friend, and has been stationed at Anne’s side all afternoon, ready to assist. She is unable to get as sure a grip on the crust, however: the baby has mushed it to paste and there is nothing to do but wipe the mess off her hand on the grass.

‘Not such a prize after all,’ says Mrs Jennings. ‘Too bad.’ Catherine’s nurse reaches into her pocket and produces another crust, which the baby snatches.

Anne can hear her sister Mary, still engaged in her tête-à-tête with Mrs Frances Apsley. She is admiring the cornelian ring Mrs Apsley is wearing, saying how well it becomes her, how it draws the eye to her elegant hands. Having Mrs Apsley to love makes Mary happy; if you are to make a proper figure at Court, having someone to love is essential, and there are right and wrong ways to go about it, as there are right and wrong ways to dress, to walk, to dance, and to play. Anne strikes a thoughtful chord, catching first Mrs Jennings’s eye, then Mrs Cornwallis’s.

‘Your Highness.’ It is Mrs Jennings. ‘Will you play the whole tune, or are you meaning just to thrum at us?’

‘Oh yes indeed, do play us the tune!’ cries Mrs Cornwallis. ‘It’s a new one, isn’t it? You play so well, it is always such a pleasure to listen!’

So Anne plays the rest of the piece, for the company, and the baby, and for Mary Cornwallis.

From Lady Anne of York to Mrs Mary Cornwallis

Wednesday five a clock

I have said that I have gone into my closet to pray but I must write to you my dearest friend, if Mary can write to Mrs Apsley then I do not see why I should not write to you. Fate has cruelly parted us since this morning but in a letter I might yet tell you my heart. I will send this by the hand of Mr Gibson the drawing-master, you must know him, he is a dwarf.

Your affectionate friend,

Anne

The Duke’s Dogs

It is an early afternoon in August, nearing the end of another Windsor summer, and Anne is on horseback. She has her usual mount from her father’s stables, a roan jennet named Mercy, quiet, comfortable and surefooted, with the character of a perfect lady, in horse form or in human. They have been hunting together since early morning, and in all this time Anne has only persuaded her to canter twice, and to gallop not at all. The truth is that the Duke does not wish her to gallop: that is why he has had her mounted on Mercy, and accompanied at all times by a trusted equerry, a portly older gentleman the Villiers girls call Wheezing Warner. They might laugh as much as they like today: Anne won’t hear them, because despite the twin impediments of Mercy and Warner, she has long since left them behind. And Mary too. One of the chief pleasures of riding, for Anne at ten, is in leaving Mary behind.

Another is the knowledge that, even though he has ordered the impediments, her father is proud of her when she joins him in the field, is delighted that one of his children, at least, loves sport as much as he does. He has no living sons, but in her riding habit, with its buttoned-up doublet, long-skirted coat, boots, hats and periwig, Anne could be both son and daughter. Only her petticoat gives her sex away. She doesn’t resent it on that account, although she might wish that it weren’t so heavy, or so hot.

The sun is at its highest now, and the day is growing overripe. There is a glare about that draws the water from her eyes, and powerful smells are rising off the coats of horses and gentlemen, and – though one should never say so – off the coats of ladies too. Mr Warner is wheezing especially hard, and there is a dampness on Mercy’s neck. Anne feels as if her own blood-heat is trying to rise out through her skin to join the heat outside. But they have come to a stop finally, the stag they have pursued for five hours is harboured in a thicket, and they are all gathered outside, waiting for the huntsman to drive him out.

Waiters have jumped down from their wagons and are moving among the riders with refreshments. Mr Warner hands Anne a mug of small beer; she drains it with what Mary, or Lady Frances, would say was unseemly haste.

‘The stag is tired, Your Highness,’ the equerry says, as he takes the mug back. ‘I think we are nearly at the end.’

Anne nods slowly. ‘Yes,’ she says. ‘Besides, he’s old. He’ll not stand long before the hounds.’

She expects Warner to say at this point that her knowledge puts him to shame, and he does. Then she nudges Mercy forward a little, so as to be nearer to her father, and have a better sight of his dogs.

They have had a hard day of it. The stag’s great age has been evident not only in his girth and magnificent crown, but also in his cunning: he has in the course of this one morning’s hunting run straight into the middle of three different herds, and on two of those occasions confounded the hounds completely, so that it has taken some time for them to pick up his scent again; too many times to count he has doubled back over his tracks and then back again; once he had even headed straight for the river and it had seemed for a moment that he was about to take soil, but at the last moment, in a move the hunt had come to recognise as his signature, he had doubled back again.

Now they have tracked their quarry to the entry in this thicket, and the scent is strong. They have run up to the entry, and pulled back again, bawling: they believe that the stag is there. The sound of a pack in full cry, each animal barking as if tuned to a different note, all the notes moving with and across and after each other in agitated counterpoint, is Anne’s favourite sound, and it charms her further and further forward, until she is close enough to discern each broken bough at the entry, close enough to see the huntsman stop to check the footprints, to make sure that the hounds are baying for the right beast, close enough—

‘Anne – get back this instant! Warner! What are you about, man?’

It is the Duke’s voice, half-fear, half-rage, and louder even than the hounds. She pulls back at once, and goes to beg her father’s pardon, but he has not quite finished being angry yet.

‘What did you think you were doing, girl? Have I not taught you better? Do you have a sword now, do you? Do you?’

Anne opens her mouth and shuts it again.

‘Well, do you have a sword? A stick? Anything? Are you armed?’

‘No, Sir.’

‘No, of course not, so when the stag is unharboured, when he rushes out of that entry, when he comes at you with his great horns, what will you do, Anne? What. Will. You. Do?’

His face is very red: it might be the heat, or the beer he has been drinking all morning – he is blowing the smell of it into her face as he shouts – or then again perhaps she and her foolishness are the cause of all of it. She finds she cannot say or do anything in response, except turn redder herself.

They hold each other’s gaze for a moment, the red-faced Duke and his ruddy daughter, mouths firmly shut, one enraged, one sullen. Then Henry Jermyn, the Duke’s Master of the Horse, appears at his side, ready to soothe and to charm. Anne has never understood what is supposed to be so charming about him, but he does amuse her, if only by having ridiculous short legs and an enormous head. Next to her stately father, he always looks especially absurd.

‘No harm done, Sir,’ he says to the Duke. ‘She is in one piece still, and – if you will permit me to say so – Her Highness’s spirit and grace in the field, the figure she makes on horseback must be such a source of pride, and were she my daughter—’

‘That’s enough, Jermyn. You’ve stuck the point. Anne, I will not send you back for now but you must stay where you are. Warner, mind she goes no further.’

The Duke and Jermyn turn their horses round, and at the very next moment there is a shout from the huntsman: the stag is unharboured.

Anne turns in time to see him take a few, stiff steps forward, then stop and stand, facing the hounds, who know the danger in their well-trained sinews, and hold back. While the hounds and stag face each other, the huntsman runs to the Duke and Jermyn; they put their heads together for what can be no more than a minute but seems much longer, and while they do so nobody else speaks, no animal moves. The huntsman nods, and signals to his men, who in turn call the hounds back softly, and couple them. And as they do so, the Duke is carefully, quietly drawing his sword.

The exhausted stag, whose fear has driven all his cunning out, turns his head at once to flee, but the Duke has galloped up already, and his sword drives home.

Now the Duke dismounts, and the huntsman hands him a shorter blade, a hunting knife. He cuts the stag’s throat, then he bloods the youngest hounds. Then the Mort