8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

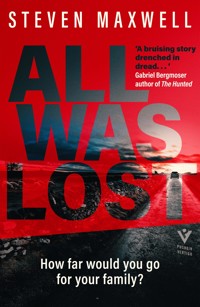

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

OBSERVER THRILLER OF THE MONTH SUNDAY TIMES CRIME CLUB PICK A HEARTSTOPPING, GRISLY MOORS THRILLER ABOUT A WOMAN WHO WILL STOP AT NOTHING TO GIVE HER DAUGHTER A BETTER LIFE _______ 'Fast paced and shocking' Observer A brilliant example of Northern noir' Sunday Times 'Dark, grisly and utterly compelling. Thriller writing at its finest' CAROL WYER 'A bruising story drenched in dread. . . recalls Cormac McCarthy in its drive and brutality' GABRIEL BERGMOSER 'Dark, fast-paced and thrilling' ALAN PARKS _______ THE CASH IS GONE. THE HUNT IS ON. HOW FAR WOULD YOU GO FOR YOUR FAMILY? Orla McCabe has found a case of money. Willing to do almost anything to give her family a better life, she flees with her husband and baby daughter - and the money. Meanwhile, detectives Lynch and Carlin are investigating a botched human trafficking deal on the isolated northern moors. They find piles of bullet-riddled bodies, but no cash. The owners of the money are on the hunt, and soon a world of brutal violence envelops Orla and the detectives. To secure her daughter's future, Orla will never stop running. It's just a matter of who she drags into the dark with her. . . This promises an adrenaline ride like no other - Deliverance meets The Hunted set on isolated northern moorland - for fans of Elly Griffiths, Adrian McKinty and JM Dalgliesh

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Her rash hand in evil hour Forth reaching to the fruit, she plucked, she ate: Earth felt the wound, and Nature from her seat Sighing through all her works gave signs of woe, That all was lost.

Milton, Paradise Lost

Contents

All Was Lost

67

The detectives looked through the glass. The glass was one-way and beyond was a purpose-built chamber. The chamber’s walls were concrete block fitted with ringbolts and against the far wall lay an iron-frame bed, thin mattress wrapped in plastic, headboard hung with manacles. Gazing down at what lay piled beside the bed on the poured concrete floor was the cold glass eye of a wall-mounted camera.

‘What are we talking here?’ Lynch said.

They were standing in the viewing room, a dark and narrow space that ran the length of the chamber, and maybe out of reverence for the dead or owing to the oppressive dimensions of the room, both men whispered when they spoke.

‘Communication breakdown,’ Carlin said. ‘Transaction failure.’

Male and female. Some barely adults. A death-camp pile yoked together by their necks with collars and chains. Their hands and feet manacled. At least three of them had fresh purple scars hacking across the sides of their torsos. All had track-marked arms. All had been branded. All had been shot in the head. The blood under them flowing off into the trench drains had dried brown and begun to crack at the edges.

‘No sale, kill the product,’ Lynch said.

‘Don’t call them that. Just because they were treated like meat doesn’t mean we talk about them like meat.’ 8

‘I know. Sorry.’ Lynch gestured to the small metal desk beside them where a high-end laptop linked to the chamber’s camera had been shot through its keyboard. ‘Wonder if we can pull anything off that.’

‘We’ll see.’ Carlin opened the steel door that led upstairs and looked back at Lynch, waiting for him to follow. ‘Let’s go.’

Lynch didn’t move. He stood staring through his reflection in the glass at the murdered who lay callously exhibited in the dead fluorescent glare. One young woman naked from the waist down, sweater ridden up exposing the thin smile of a fresh caesarean scar. He guessed he was no more than five years older than her. His fists whitened.

‘Lynch.’

He came to and followed Carlin out of that bleak cubbyhole and up the concrete steps to the hallway where polished oak boards creaked under their shoes. Below brass picture lights, framed paintings of foxhunts hung from the burgundy walls of the hallway. A hooded forensic scientist in white coveralls approached carrying a clear plastic bag containing an old Nikon F camera and several 35mm film canisters.

‘These were found under the console table,’ she said.

‘Outside the living room?’ Carlin pointed down the hallway. ‘Right there?’

‘Yep. Maybe nothing.’

‘Maybe something.’

In the doorway of the green-painted living room, they looked anew on the carnage before them. Several men dead among scattered pistols and rifles and shell casings. Sound suppressors had been fixed to most of the guns. Some had their eyes open and looked as if they were about to talk, mouths frozen in speech. Two wore dark suits and Kevlar-lined leather gloves, white shirts 9blood-soaked. One of these men supine on the chesterfield couch still gripping a pistol, gut-shot, his entire midsection darkly drenched. The other on his stomach across the rosewood coffee table, the back of his head blown out, bits of skull and brain strewn about him. Curled under the table was a man wearing a black Adidas tracksuit who’d taken one in the throat. Two others wearing boilersuits and steel-toe boots had each been shot in the chest. On a sodden rug beside the stone hearth lay a biker in leathers with a spiderweb bullet hole punched through the mirrored visor of his full-face helmet and the helmet was flooded. Blood everywhere.

‘No wallets, no licences,’ Lynch said. ‘No ID at all.’

Carlin looked at the suited man dead on the chesterfield, holding the Ruger pistol. He looked about the doorway he and Lynch were standing in and then behind them at the door across the hallway pelted with bullet holes. He looked at the floor in the hallway and the console table under which the camera and canisters had been found.

‘Get these developed.’ He handed Lynch the plastic bag.

They stepped out of the shooting box and into the gritty light of a vast northern moor. Cold wind. Dawn sun boiled low in the sky yet offered only cold light and long shadows. A helicopter hung nailed to the sky, blades stirring the air, and then it was leaning forward, nosing towards the horizon, and banking sharply.

‘The air smells funny without the fumes,’ Lynch said. ‘Too clean. Never thought I’d miss the city.’

Carlin inhaled and looked around. ‘I could get used to it.’

They milled about the moorland and then turned and headed back, slowly, absorbing the grim acreage about them. Exposed gritrock risen though the dried heather and crowberry shrubs resembled great scabs grown across the back of the land. Small 10dark birds like windblown leaves blew over the burnt-yellow moor grass. Deep drainage grip channels coursed through heath and blanket bog. On the horizon of that spectral garden rose distant scarps and the ruins of an abbey.

The shooting box was a grand double-fronted building of many rooms and a chamber. Stone tile roof. Four chimneys. Floodlight above the front door. Abandoned beside the building sat four vehicles: two Audis, a Ducati superbike with jacked-up suspension and off-road tyres, and a Scania flatbed truck laden with eighteen 55-gallon drums. A tyre stabbed flat on each vehicle had left them slumped in the raked gravel, the superbike fallen on its side.

At the gable end they stopped at the body of a suited man dead on his belly between an Audi and the shooting box.

‘Looks like he got the furthest,’ Lynch said.

‘Apart from her and the baby.’ Carlin pointed his thumb over his shoulder.

Lynch turned and looked across the moor to where the other crime scene, smaller yet no less grim, had been cordoned off. The mother and daughter hikers who’d found the bodies and made the call were talking to uniformed officers among a fleet of ambulances and cruisers, lights strobing vibrantly in the pale light.

The woman lay sprawled in a peat bog, pink hair flecked with blood flowing across the sedge. Ligature bruises clouded under the skin of her wrists and ankles. Scarfed about her throat hung a spit-soaked gag and a blindfold. A gutter dredged through her cheek as if by a chasing bullet. In her back, her latissimus, gaped a ragged black hole. This bullet had perforated her torso and entered what she’d been carrying. Mute in her track-marked arms lay a dead newborn. Both had been branded.

‘Fucking men.’ Lynch spat in the grass.11

Carlin looked at him. ‘Bury that shit now. You hear me?’

Lynch grunted and looked away.

‘I mean it. Bury it now or it’ll eat you alive.’

Clouds massed into mountains and their immense shadows crossed the moor and the temperature, already low, dropped another couple of degrees.

‘One thing that doesn’t make sense,’ Carlin said.

‘Just one?’

‘There doesn’t appear to be any money involved. I mean, if this is some trafficking deal gone wrong, where’s the money?’

Lynch thought about this. ‘Maybe the money side of the deal was made over the phone or online. The laptop.’

The helicopter came back and swooped in low, the grass careening in the blades’ backwash, and then it was rising again and moving off, leaving behind a thrumming silence.

Lynch’s phone sounded. He took it out and looked at the caller ID. Kat. He pocketed the phone without reading the text and cleared his throat.

‘Just one of the lads.’

‘I didn’t ask.’ Carlin was examining the dead man’s outstretched hand. The wrist and digits bent in abnormal articulation. ‘What do you think?’

Lynch put on nitrile gloves and sat on his heels in the blood-spattered gravel and inspected the splayed hand. ‘Looks like his fingers were prised apart. Couple feel broke. Like someone was trying to take something from him.’ He stood up. ‘A gun?’

‘Maybe.’

‘So what we have here is potentially missing money and a missing gun.’

‘Which means?’

‘We’re missing a man. Or men.’12

‘And maybe a couple of other vehicles.’ Carlin nodded at the ground.

Lynch stepped back and looked at the marked-off tyre tracks intersecting gravel and grass. ‘More off-roaders. Big. Probably a Land Rover. The others, not sure.’

The clouds shifted and the sun flared and hit the truck. They squinted at the gleaming steel drums loaded on its back. All empty.

‘You think them people in the chamber were inside those?’ Lynch said. ‘Transported in them?’

Everywhere seemed to stop and fall quiet. A breeze in the downy cotton grass. The helicopter now a far-off murmur high over the distant abbey ruins.

Carlin didn’t answer.

‘Drums lined with Teflon,’ Lynch said. ‘I mean, what are we talking here, acid baths? They were going to dissolve them?’

Carlin palmed flat his thin grey hair and shut his eyes. He still didn’t answer.

66

The Banskin brothers stood waist-deep in the river mouth under a pale dawn sky. Dark hair and beards dripping wet. The smaller of the two stood very still, bloodstained hands at his sides in the cold water, eyes shut. The larger one hulked nearby laving handfuls of brine over his head, light catching in the droplets and in the stones of the pilfered rings he wore on every finger. 13Three blurred tattoos marked their left forearms. Old flogging scars criss-crossed their backs.

A dog barked and the men turned. On the crest of the riverbank stood a man about sixty with a Dobermann. With an expensive leather shoe, he distastefully toed their bundled clothes and canvas kitbags. He wore a wool overcoat and a flat cap and carried an engraved double rifle. A seigneurial air about him. The dog had a docked tail and cropped ears permanently erect and when it barked again, the man stroked its sleek head.

‘When you lads are decent I’d like to talk,’ he called.

While the brothers dressed in filthy clothes, the man, who went by Cyrus ‘Cy’ Green, shouldered his rifle and swatted midges as he looked out across the estuary to a remote hill range that had taken on the same watery blue haze as the brightening sky.

Then he spoke, telling of an ‘unholy fuck-up’ at a moorland shooting box the night before, and they listened and they watched, and when he finished talking, Dolan, the smaller of the brothers, pulled on a dark green oilskin poncho and put up the hood.

‘Why you telling us?’

‘Before any pigs could come snuffling through the truffle patch, I spoke to one of my lads. He was gut-shot but still kicking. Said someone was in there taking photos. A woman. Said he shot at her but doesn’t know if he hit her or not.’

‘So?’

‘So I want you to find her.’

‘Why?’

‘I suspect she has something that belongs to me.’

Dolan knuckled a nostril and blew out a string of snot. ‘What something?’

‘What that something always is.’14

The elder brother, Joseph, finally spoke: ‘Animals piss on things to mark territory, to show submissiveness, to claim ownership.’

Cy squinted between the men. ‘You’re saying I should have… pissed on my money?’

They said nothing.

‘I checked high and low and didn’t find a penny. However’—Cy held up a driving licence—‘this I did find. Was in a rucksack on the floor. Don’t know if she’s just stumbled into this shit or she’s been playing us all along. Either way, find her, I believe I find my money.’ He handed the licence to Dolan.

They looked at it.

Orla McCabe. Thirty-five years old.

‘You know where she lives, talk to her yourself,’ Dolan said.

‘A message needs broadcasting loud and clear to any weaselly cunts who think they can cross me.’ Cy took off his flat cap and touched his dyed-black hair and smiled with only his mouth, teeth small and grey, well used. ‘Your eminent presence is that message.’

They conferred in silence while Cy looked west at the clouds gathering over the distant mudflats and the thunderous sea beyond. The dog hadn’t moved an inch or taken its eyes off the brothers. It stood rigid in its steaming gloss coat while vapour from its breath wreathed its head. Cy glanced at the men out the corner of his eye and then looked away again, back to the mudflats, feigning interest in the littoral wastes of the rolled-back sea.

With Cy looking away, Joseph bent at the waist and reached into the tall grass. The dog’s head followed him. Cy turned back, holding his cap, and was about to speak when Joseph rose and swung the curved blade of a sickle into his neck and pulled him to his knees in the glasswort. The speed of the attack shocked open Cy’s mouth and eyes. Cap and rifle hit the ground. The dog leapt. 15Dolan put a boot in its muzzle but it recovered quickly and went for him. This time he kicked it hard in the head and it yelped and backed off. Joseph jerked the blade free in a welter of blood and stropped the dripping steel on his thigh, while Dolan knocked aside Cy’s flailing hands and strangled the rest of the life from him, arterial blood running through his fingers. The whites of Cy’s eyes clouded red as capillaries ruptured.

They hauled the body down the bank to the inlet and cast him out into the silted depths. Insects blowing out of the reeds on cellophane wings. They stood watching blood ribbon and disperse through the turbid water while the dog paced the riverside, baying and whining as its master went under. Incurious gulls soared the soft blue void on invisible axes. They threw cap and rifle into the water and then ascended the bank and retrieved their kitbags and went to the dead man’s grey Land Rover Defender.

The vehicle was fitted with roof lights and a bull bar and sat on a dirt road beside the cat’s cradle of a felled pylon dissolving to rust. Keys still in the ignition. Joseph started the engine and Dolan tapped Orla McCabe’s address into the GPS. The Defender accelerated and then braked and a rear door swung open. Dolan whistled and the dog sprang soaked from the reed bed and galloped up the bank. It stood staring at him through the open door, head cocked in strained contemplation. Then it shook itself dry, barked once and jumped in. The door shut and the Defender vanished.16

65

Six hours ago Orla McCabe was standing at her kitchen table looking at the money in the case. The money lay stacked in a block the exact size to plug the hole beaten through the middle of her life. She wiped her arm across her sweaty face and looked at the case itself. A brutal thing, deep and bulky, like something a paramedic would lug. Bright orange shell made from some type of thermoplastic polymer. Unbreakable, watertight. Black foam lining imperfectly cut to accommodate the money block. She shut the case and went upstairs.

In the doorway of the box room at the back of the house, she stood watching her baby sleep. A flickering street light intermittently laddered the room through the vertical blinds. At the cot she kissed her fingertips and touched them to the baby’s forehead. The baby flexed a chubby paw and made a noise in her throat.

Orla switched off the TV in her bedroom and watched Liam sleeping fully clothed on top of the covers. Was she in his dreams like he was in hers? She often wondered this but never asked. Afraid of the answer. She was covering him with the blanket when he asked her the time.

‘It’s late,’ she said. ‘Has she been okay?’

‘Yeah, she’s fine. I’ve been calling you. Where’ve you been?’

She walked around the bed and held him. He reached out and stroked her shoulder. She pressed her cheek against his beard.

‘You okay?’ he said.

She said nothing.

‘Get in bed,’ he said. ‘I can feel the cold coming off you.’

‘Come downstairs.’17

‘What for? What’s wrong?’

‘I need to show you something.’

After she’d shown him what she’d brought home with her from the moor, she packed a bag while he called his Uncle Fran. She’d never met the man and Liam himself hadn’t seen him in years but they’d no one else to turn to. They lived small lives. The phone call was difficult for Liam and no doubt for Fran given the nature of the call and the hour.

She watched him standing there in T-shirt and boxers, holding his neck and looking down at the baby’s clothes scattered across their bed. He saw her behind him in the full-length mirror. She put her arms around his waist and leaned her head on his shoulder. They shut their eyes and swayed on the spot. As if nothing was happening.

‘We must be out of our minds.’ He broke their embrace and turned to face her. ‘We’re doing okay.’

‘How can you say that with a straight face? Are you forgetting how much debt we’re in? We had our house repossessed, our first home. You’ve got a month left on the job you’re on and then what, another six-month contract and you’re out on your arse again?’

‘I’ll find something else.’

‘What about me? You think I’m happy emptying bins and cleaning toilets? You said so yourself, you can’t take being bounced from pillar to post any more. Well, neither can I. It’s demeaning. Our lives are built on sand. That money is stability.’

‘We can’t do this.’

‘You can’t work on building sites, living hand-to-mouth all your life. You can’t do it. I know I can’t. Not for the next thirty-five years.’ Her eyes sharpened. ‘Scum take what they want. Maybe now and then, we should stop being so pathetically nice and take 18what we want. You know what the worst thing is about having no money? It isn’t that you don’t own things, it’s that you don’t own yourself.’

He looked at her with an expression of anxiety and confusion that left her stomach cold. Her eyes softened.

‘Look, that money’s a lifeline,’ she said. ‘Think what we can do with it. Debt gone, like that. We could put her in a good school. Private health care. I could start my own photography business. You could go to college or do whatever you want. We could buy a house again instead of pissing our money down the drain renting. We could start again, Liam, start properly.’

She took his cold hands and kissed them.

‘Do you want to slave away for some boss for the rest of your life who drives a car worth more than people’s houses?’ she said. ‘Do you want to spend every waking hour worried out of your mind about money? Having a fit every time a bill arrives or the van breaks down or she needs new clothes. Do you want her to grow up like us? Slaves with no opportunities. Grinding away in thankless jobs for rich pricks and then numbing ourselves to death in front of the telly. Is that what you want?’

She didn’t give him time to answer because she knew he could be persuaded. He just needed a push.

‘And then she goes to that shithole school on the corner and the manners and good ways we’ve taught her make her an easy target because we should have taught her to be scum like the rest just to fit in. It’s easy being scum because they don’t have any ambitions or expectations, but we do. It’s just our bank account says otherwise. Our bank account says we’re as useless and hopeless as the filth we live beside. Ambition is a disease and money the only cure. With that money, we’re better people. With that money, she gets to live the life she deserves.’19

‘How do you put that kind of money into the bank without people noticing?’

‘We buy everything in cash.’

‘What, for ever? A house? School fees? Are you serious?’

‘I don’t know.’ She shrugged. ‘Yeah.’

‘We’d have to deposit it in dribs and drabs. Open up a few bank accounts.’

She squeezed his hands and he squeezed back.

‘We need to go,’ she said.

She got her phone from the living room windowsill and was putting it in her jacket pocket when the nightmare image of men in a van tracing her calls stopped her dead. She looked around the room and focused on the couch. The image hit again and she switched off the phone and set it under the middle seat and looked out the window. Nothing. Just wind, darkness.

Under the dull ochre wash of the street lights, they loaded their bags and the case into the loadspace of his old Transit van, the case wrapped in a bedsheet and stowed in the furthest corner. She got in the front with the baby while he went back to the house to lock up. A train thundered by over the high brick wall at the end of the street, a wall daubed in graffiti and topped with flakes of bottle glass embedded in cement.

A new world was unfolding in her skull. A world of immunity and choice. The dead weight of frustration and anxiety and pessimism rising, dispersing. Money worries that had run on for years now seemed trivial, easily solvable, hardly worth considering. Their baby’s future now looked a colourful and bright place with a surfeit of opportunity and choice. For the first time, she felt weightless. She tried not to think of the infernal machinations that must have gone into getting the money into the case, the intended transactions, the logistical planning, the underground 20meetings, the earnest promises, the smiling lies. She needed to focus on now, on their lives. Lives augmented.

The lights went out in the house windows and he emerged and locked the front door. He got in the driver seat and sat looking back at the house while absently putting on his seat belt. She helped him buckle up and then she locked the doors and he started the engine. She looked down at the baby awake beside her, tired eyes lost in the middle distance.

‘I can’t believe we’re doing this,’ he said.

She held his hand on the gearstick. ‘It’s for her, Liam, not for us. It’s all for her. Remember that. It’s all for her.’

The baby opened her eyes and saw them there and her face crumpled and she looked as if she were about to cry, but sleep swallowed her consciousness and she slipped back under.

Liam switched on the headlights and pulled away into predawn darkness. While he drove, Orla reached down into the passenger door compartment and carefully rearranged something in there and then sat back and looked out the window into the onrushing dawn.

64

Almost noon. The blinds in the police station were open but the city skyline was blocked by the courtyard walls that held the carriers and the vans and the cruisers below. The urban roar beyond resonated through the glass. Car alarms, blowing horns, roadwork, the airport flight path. After thirty-five years 21Carlin was used to it. He wouldn’t miss it when he was gone but he was used to it.

He sat alone in the office, drinking vending-machine chicken soup from a plastic cup, bifocals hanging on the end of his nose. He was studying a series of monochrome photos developed from the film canisters found with the Nikon camera in the shooting box. Photos of moorland and reservoirs, outcrops and gritstone walls, limpid brooks, moorbirds. Photos of an abbey in ruins. Photos of the shooting box’s exterior. Photos of the vandalized and abandoned vehicles and their plates. None of the dead in the living room or the concrete chamber. Why?

He thought about this, picturing the suited man on the chesterfield aiming the gun at the doorway, the bullet holes, the positioning of the camera and canisters on the hallway floor. He guessed a dying man lying there firing a gun would probably prevent him from taking photos too. He picked up a pile of monochrome photos developed from another of the canisters.

Candid images of a woman, mid-thirties, sitting on a swing. Then a man laughing while driving a van. Another of her sitting with the man and a newborn on a blanket in tall grass, the photo taken at arm’s length by the woman, the two of them smiling over the sleeping child, the low sun flaring behind almost darkening the woman from the image. To Carlin’s eye something was wrong with their smiles.

He looked at the framed photo of his own family. Wife, daughter, granddaughter. They should not occupy the same abyssal plane as these photos. He knew better. He was putting his own photo in the desk drawer when Lynch came into the office, eating a bacon sandwich folded in a greasy napkin and carrying an envelope. He pushed the envelope across Carlin’s desk and tapped it.22

‘There’s the address,’ he said.

Carlin opened the envelope and took out a sheet of paper and a monochrome photo of the same young woman, this time holding the baby and leaning back on an old Transit van. He looked at the van’s plate in the photo and at the address scrawled on the paper.

‘It’s still registered to them?’

‘Yep.’

‘At this address?’

‘Yep.’

‘Mortgage?’

Lynch finished chewing and swallowing his sandwich before answering. ‘Rental.’

‘You tried calling them?’

‘No answer.’ Lynch wiped his hands and mouth on the napkin. ‘Maybe they’re out shopping.’

‘What about the landlord?’

‘A few late payments, nothing weird. Said she hasn’t heard a peep from them in months.’

Carlin set down the photo and the paper. ‘What about the camera in the chamber, the laptop, any luck?’

‘Computer forensics is on it.’ Lynch spun a couple of the photos around to face him. ‘Black-and-white film, old school. They’re pretty good. By the way, I looked into the phone records for the shooting box.’

‘And?’

‘There are none. It’s never had a landline. They might have used wireless or something. We’re looking into it. For now, it looks like if there was money, it was right there in the middle of bedlam. Speaking of which, I take it you heard about the passports.’

‘What passports?’

‘At the shooting box.’23

Carlin took off his glasses. ‘What are you talking about? We’ve just got back from the shooting box.’

‘Forensics found them after we left. They didn’t tell you? I thought they would have told you.’

‘Jesus, lad, get to the point.’

‘About fifty Eastern European passports were found taped to the biker under his leathers. Serbian, Latvian, Croatian. You name it.’ Lynch looked at the photos and ran a hand over his expensive haircut. ‘This is big, isn’t it?’

Carlin picked up the photo again.

63

They drove with the baby asleep between them. The rumble of the engine and the road beneath them a meaningless drone, white noise. Orla sat looking out the passenger window at a vast petrochemical plant out on the edge of the sea. She felt drugged and unreal with lack of sleep and adrenaline. It was Liam who finally broke the silence.

‘How do you go to take photos of a church and come home with a case of money?’

‘It was an abbey.’

He looked between her and the road, his face stone. ‘Don’t, Orla. I mean it. We fled our house. Our home.’

‘It’s only a rental.’

‘Only?’ His voice rose sharply over the syllables.

‘You’ve got to trust me.’24

‘You think I don’t? I’m here, aren’t I?’

‘I know.’

‘Then trust me.’

‘I do trust you. It’s just…I found it, okay? That’s all you need to know.’