0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Passerino

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

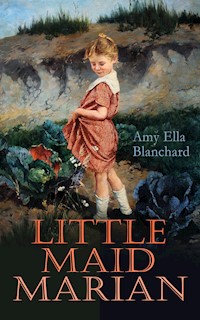

Little Maid Marian is a children's novel by

Amy Ella Blanchard, published in 1924.

Amy Ella Blanchard (June 28, 1854 – July 4, 1926) was a prolific American writer of children's literature. Amy Ella Blanchard was at first a teacher of art in the Woman's College in Baltimore, now Goucher College. She taught school while studying art.

She then taught drawing and painting for two years in Plainfield, New Jersey.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Amy Ella Blanchard

An Everyday Girl

A Story

The sky is the limit

Table of contents

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

CHAPTER XV

CHAPTER XVI

CHAPTER XVII

CHAPTER XVIII

CHAPTER XIX

CHAPTER XX

Amy Ella Blanchard

An Everyday Girl

A Story

1924

Digital Edition 2023

Passerino Editore (Edited by)

Gaeta 2023

CHAPTER I

A FAMILY DISCUSSION

Ellen settled herself on the most uncomfortable chair in the room for the simple reason that it was the only one left her, the others being occupied by her elders, relatives of various sorts. She pulled down her skimpy black skirt over the length of rusty-looking stockings which covered her long legs, and gave herself up to a survey of the articles in the room. There were so many little gimcracks that Ellen considered she could entertain herself by looking at them while the others talked and talked. She was not interested in the conversation at first, but suddenly she withdrew her gaze from a group of wax flowers and fruit under glass, and sat up very straight. They were talking about her!

“Being a bachelor whose housekeeper would leave if a child were foisted upon her care, I couldn’t consider taking her, housekeepers not growing upon every bush these days,” said Mr. Josiah Crump, a bald-headed pot-bellied old gentleman.

Ellen pictured a bush with housekeepers dangling from it, and wondered what such might be called.

But this fancy left her when Mr. Crump continued, “I always liked Rosanne and haven’t a thing against her daughter, but I never cared much for that artist husband.”

“Gerald North was a dear, a perfect dear,” spoke up pretty Mrs. Lauretta Barton; “I always liked him and so did Bobby.”

“No business sense; impractical,” Mr. Crump differed with her. “No man has any right to go off to war and get killed, leaving his family unprovided for; it makes it very awkward for them, and furnishes an unpleasant subject for the relatives to contemplate. I don’t believe in having unpleasant subjects brought up when they might be avoided.”

“I don’t like unpleasant subjects myself,” sighed Mrs. Barton, “but they have to be faced when they are thrust upon you. I wish I could advise, or, indeed, assume the responsibility of the child myself, but in my delicate state of health it would be impossible; it would be entirely too great a task.”

“Delicate fiddlesticks!” broke in Miss Orinda Crump. “What you need, Lauretta, is some vital interest to take you out of yourself.”

“If only Bobby were living,” murmured Mrs. Barton.

“Which he isn’t,” pursued Miss Orinda, “and it doesn’t do you any good to brood over your loss, or to magnify every little ache and pain; you’ll end in a sanitarium.”

“But I do suffer; you don’t know,” complained Mrs. Barton plaintively.

“From lack of exercise, rich food, and nothing to think of but your own self,” continued Miss Orinda. “If you had to hustle for your bread and butter, and turned your thoughts out instead of in, you’d find life more interesting; but when your hardest exercise is cutting off coupons, and your chief interest is in germs, vitamines, and X-rays, what can you expect? As I see it, it’s up to you to adopt Ellen. Don’t you think so, Uncle Jo?”

“H’m, well, each must be his own judge in such matters,” replied Mr. Crump, leaning back in his chair and placing the tips of his fingers together. “I believe in freedom of thought, in——”

“Oh, do shut up, Jo,” said his sister, Mrs. Ed. Shirley, a stout, comfortable, well-dressed woman. “Once you get off on one of your harangues there will be no stopping you. Of course every one knows that, with my big family, I couldn’t be expected to take the girl. It is as much as I can do to manage my own brood, so count me out, Orinda.”

“I don’t see why you all constitute me chairman of this meeting,” retorted Miss Orinda. “If age has any prerogative, it isn’t up to me to preside.”

“Well, it’s your house, and you got us here,” returned Mrs. Shirley.

“To read you the letters from Dr. Markham and Mr. Barstow, that you might understand how imperative it is that Ellen should be provided for at once. You all have your own cars, so it was no effort for you to get here.”

“What is the matter with her Uncle Leonard? Why isn’t he here? He is nearer of kin than we are, and has no children,” Mrs. Shirley went on.

“He has sea duty for two years, and I don’t know where he is.”

“Well, there’s his wife.”

“She is with her people in California. She will stay till he gets back, and anyway——”

“Where are her father’s people? Why don’t they come forward?” Mr. Crump again came into the conversation.

“His parents are dead, and he was an only child. If he had any near relatives, we do not know where they are.”

“Humph! I understand. Well, as far as I can see we’d better put the girl in some good institution; there are plenty of them. What with taxes and the high cost of living it isn’t up to any of us to increase our expenses.”

Ellen smothered a little cry of dismay and clenched her hands. An institution! She choked back her tears. She must be brave. She must not let them see.

There was a moment’s complete silence. Mr. Crump sat with his hands clasped over his ample front, his eyes fixed on the ceiling, and an expression which said, “The oracle has spoken.” Mrs. Shirley looked across with a satisfied smile at Mrs. Barton, who lifted her hands and let them fall helplessly into her lap, intimating that there was nothing further to be said. Miss Orinda alone looked at Ellen, who sat with downcast eyes, clenched hands, and a heaving breast.

It was but for a moment that Miss Orinda regarded the girl; then she sprang to her feet. “Rosanne’s child shall not go to an institution!” she cried. “Take off your things, Ellen. You are going to live with me, and pray Heaven you will make a capable, useful woman.”

Ellen’s mute misery changed to an expression of intense relief. “Oh!” she breathed tremblingly.

“Well, that’s good of you, Rindy,” declared Mr. Crump, rising from his chair, “though, after all, you are the best fixed to give the girl a home. You live alone, own your own house, have a garden, and in this little place living can’t be as high as in the city.”

Orinda tossed her head and looked at him scornfully from under half-closed eyelids. She gave a little bitter laugh. “Of course,” she replied.

“Well, Susan,” said Mr. Crump, turning to his sister, “we may as well be getting on; it’s right smart of a ride, you know. Good luck to you, Rindy. Good-by, little girl. You’ve got a good home, and I hope you’ll appreciate it.”

Ellen answered never a word, but stood in silence till all went out, Mrs. Barton drawing her handsome furs about her as she entered her shining car. She nodded and smiled her farewells as the car bowled off, following the less elegant one of Mr. Crump. Miss Orinda did not stop to watch them out of sight, but shut the door hard, came back into the parlor, and stood for a moment in front of the Latrobe stove which heated the greater part of the small house.

“Well, that’s that,” she said at last. “If any one had told me this morning—— But, never mind. Maybe I’m a fool, but I’d rather be some kinds of a fool than a hide-bound, self-indulgent, cold-blooded skinflint. I rather imagine there have been worse fools in this room lately than I am. Come here, Ellen, and let’s take stock of each other, since we’re to be housemates.”

Ellen came readily. Miss Orinda held her off at arm’s length and regarded her steadily. “You’re not much like the Crumps,” she said presently. “You get your hazel eyes from your mother, but your nose and mouth from the Norths. It’s just as well, for the Crumps aren’t much for looks usually.”

“Uncle Josiah isn’t,” said Ellen in a decided voice.

Miss Orinda smiled. “No, he’d never take a beauty prize, neither would Susan. Lauretta wasn’t a particularly pretty girl; she grew up to her looks somehow; and you may, too, for you haven’t a bad beginning, though no one could call you a prize beauty either. Lauretta is about my age, a little older in fact, but doesn’t look it. If I gaumed up my skin with creams and clays, and was forever fiddling with my hair, maybe I’d look younger, but life’s too short for me to spend it messing with my old carcass, and I haven’t an eye out for the men, so there you are.”

While she was speaking Ellen was taking in her own impressions. She didn’t guess her cousin’s age; she was about forty-five, but looked older, for she used no devices for increasing her charms. She wore her dark hair straight back from her forehead, which was too high for beauty; she had somewhat small, but clear, frank gray eyes, a large nose, a straight, thin-lipped mouth, long upper lip, decided chin, was of medium height, slender, and straight. Her good points were her finely-shaped head, well set, her figure, her perfect teeth, and clear, unblemished skin. Ellen had seen the gray eyes snap and the lips compress into a hard, decided line, and concluded that some might not find it easy to get along with Cousin Orinda Crump.

But then she had delivered her from that terror which had threatened,—life in a charitable institution. Tears gushed to Ellen’s eyes as she thought of this, for she was an emotional, sensitive little body. She gave a short gasping sob. “I want to kiss you,” she faltered.

Miss Orinda patted her on the shoulder. “There, there, child,” she soothed, as Ellen put her arms around this deliverer from an unhappy fate. “I’m not much of a hugger, not having had anything but a cat to hug for a good many years, but if it would do you any good to kiss me, go ahead and do it, only it isn’t to become a daily habit, I warn you. We’ll get along all right if you’re a good child. You’ll turn out to be a real smart girl, I have no doubt, but I must warn you right this minute that you can’t expect either fine clothes or luxuries from me. We shall manage to get along somehow, I dare say, but I shall expect you to do your part.”

“Oh, I will, I will, Cousin Orinda,” promised Ellen after giving the other a much less ardent kiss than she desired to bestow.

“Everybody in this town calls me Rindy Crump, and maybe you’d better call me Cousin Rindy. What name did you go by at home?”

“Mother always called me Ellen, but Daddy often called me Nelly or Nell.”

“Ellen it shall be; that’s a nice sensible name. Now then, Ellen, bring your bag up-stairs, and we’ll get your room ready. We’ll send for your trunk to-morrow.”

Up one flight of steps they went to a plain little room furnished with a bureau, a washstand, a small white iron bedstead, and two chairs, but there was an attempt at decoration, such as advertising calendars and Christmas cards tacked on the walls, and on the bureau a very hard pincushion. The mantel held two ornate glass vases and a small bisque figure of a kneeling Samuel. The small house contained but six rooms; this one was next to Miss Rindy’s; above was an attic. All was neat and orderly.

“Now wash your face and hands,—the bathroom is at the back,—put on an apron, and come down so I can show you about setting the table,” said Miss Rindy; “then you can help me get supper.” She closed the door and went out.

Ellen stood still for a moment and looked around. This was her home! Her lip trembled, her eyes filled. She dropped on her knees by the side of the bed and gave way to a fit of weeping. It was all so different from the home she had left, a dainty, artistic one. But she must be thankful for this one; she was. Her tears were half in regret for the things which were lost to her forever, half in thankfulness for that which was now provided.

However, it was not like Ellen to remain long in the depths. She was a courageous little soul, and the past few weeks had been desperate enough to show her that the ills we have sometimes can be so bad as to make us grateful for a chance to try out those we know not of; moreover, there was a call from below. She sprang to her feet, bathed her face and hands, and went down. If Miss Rindy noticed the traces of tears she made no comment.

“Haven’t you an apron?” she asked.

“I believe I have in my trunk,” answered Ellen doubtfully.

“Well, here, put on this one of mine,” said Miss Rindy, taking one down from a peg behind the door. “Aprons are most useful members of society, they cover a multitude of sins; they ought by rights to be called charities instead of aprons.”

The apron hung far below the hem of Ellen’s dress, but that didn’t matter, as Miss Rindy remarked. “It’s the fashion now to have floppy do-dabs switching about below the edge of a skirt,” she said. “Not that I hold to such silly styles. I thought Lauretta’s dress too silly and fussy for words. Come along, Ellen, I’ll show you where the dishes are. I don’t use tablecloths; mats are much less trouble and more economical. They are in that table drawer.”

Ellen found them and laid them as directed; then the rest of the table was set and she viewed it approvingly. She liked the antique mahogany with the old blue-and-white china upon it, but still there was something missing. “Don’t you have flowers on the table?” she inquired. “We always did.”

“You did? Well, I don’t; I can’t be bothered with them.”

Ellen was silent for a moment before she asked, “Would you mind if I bothered with them?”

“Dear me, I don’t know where you’d find any. I don’t raise them; they’re like Lauretta, pretty but useless. But, pshaw! I don’t see what’s got into me, picking on Lauretta, though she always did rub me the wrong way.”

“Maybe I could find something,” persisted Ellen.

“You’re welcome to,” returned Miss Rindy from the pantry where she had gone.

Ellen opened the kitchen door and looked out. It wasn’t very promising. A few green tomatoes still hung on the vines, a scraggy apple tree bore several apples at the top, and there was a row of cabbages left in a patch at the back. None of these offered anything like a bouquet.

Ellen went down the brick walk to investigate farther, and presently discovered that a honeysuckle vine, which had strayed from the neighboring yard and hung over the fence, ventured to display a few late blossoming sprays of which Ellen took immediate possession. While doing this she observed that there was an open lot bordering on the property. It was easy to reach by climbing the low fence. An open lot always presented all sorts of possibilities, and this one, while somewhat disappointing, offered a sparse supply of blooms which Ellen was quick to gather,—two or three crimson clover-heads, a cluster of purple asters, yarrow more plentiful, and two belated buttercups. With the honeysuckle these would do very well, and when at the last several frost-touched leaves of woodbine added more color, Ellen returned well pleased.

She ran into the kitchen. “Look, Cousin Rindy, look!” she cried.

Miss Rindy turned from her task of grating cheese. “Well, I declare,” she exclaimed. “They’re nothing but useless weeds, but they’re right pretty after all. You can get a tumbler out of the pantry to put them in.”

Ellen set her bouquet proudly in the center of the table on which Miss Rindy already had deposited a plate of warmed-over rolls, a dish of stewed apples, some plain gingerbread, and the grated cheese. There was a glass of milk for Ellen, tea for herself.

It was a simple meal, but there was enough of it, and Ellen rose from the table satisfied. She helped her cousin with the dishes, and then they sat down together in the parlor. The light from the big kerosene lamp picked out the gleam of the two or three ornately bound books on the marble-topped table, discovered the gilt frames of “A Yard of Roses” and the big chromo where woodeny waves threatened to engulf a tin-like ship.

“Now we’ll talk,” announced Miss Rindy, settling herself in a heavy haircloth-covered rocking-chair. “You will have to be provided with some work to do, Ellen. You can’t sit all the evening just holding your hands in that useless way. I don’t suppose you have anything just now, but you can hold this worsted for me and meantime tell me all about yourself. Of course I know in a general way, but I want more information, if you are going to live with me. You can tell me what you choose, and I will read between the lines.”

CHAPTER II

ELLEN BEGINS TO BE USEFUL

Ellen fixed her eyes on the ruddy isinglass in the doors of the Latrobe. Certain discolorations gave to her fancy strange pictures,—a glowing sunset behind a line of trees, a burning lake beneath a cloudy sky. She wondered if Cousin Rindy ever had noticed them, but she did not ask, for her thoughts went galloping off to the little studio apartment in a big city, her home till three months ago. Now it was stripped of all its furnishings, occupied by strangers, and Ellen would know it no more.

“Go on,” encouraged Miss Rindy after a short silence. “You needn’t tell me where you were born; I know that, and I know when your parents left you. What I want to know is how you lived and all that. You went to school, of course.”

“Oh, yes, I went to school, and I studied music and French at home. Mother and Father generally spoke it at meals. Even when I was quite small I could chatter away rather glibly, for they wouldn’t let me have things at table unless I asked for them in French.”

“Much good it will do you here. I don’t suppose there are two persons in town who know a word of it, unless maybe Jeremy Todd; the Todds live next door.”

“But you were in France and must speak it.”

“A smattering, merely a smattering. I picked up a little, naturally, but most of my dealings were with our own boys, and I had enough to do without studying French grammar. Did your mother do her own work? How big was your flat?”

“Only three rooms besides the bath. The studio and two rooms were all we needed. Mother got breakfast on a little gas stove; we had just any sort of lunch, and went out to dinner, sometimes to one place, sometimes to another; that was while Father lived. It was fun to decide which restaurant we could afford to go to. If Dad was flush, we’d go to a swell place; if he wasn’t, we’d go to a cheap cafeteria, but we didn’t mind. Often we’d have a late supper. Some of our artist friends would call up and say they were going to bring some specially nice thing from the delicatessen; then Mother would make coffee, and it would be awfully jolly.”

“Humph!” Miss Rindy grunted. “What did you do when you were not at school?”

“Oh, I just knocked around, practised, of course. Sometimes I sat for Dad when he had an illustration to make, and often I washed his brushes. Often, too, we’d all go out to some exhibition or a musicale. I loved the musicales. Mother had a lovely voice, you know; she sang in a church choir, and sometimes, after Dad went, she sang at private houses.”

“You still kept the studio while your father was in France, and after he came back?”

“Yes, for he was always hoping to get back to work, but he couldn’t, though he tried. You see it was shell-shock, and he was gassed, too.”

“I know, I know,” Miss Rindy breathed. “Poor boys, poor boys, how many I have seen suffer. You kept right on in the studio then while your mother lived.”

“Yes, for she couldn’t bear to give it up; we had all been so happy there, but at last the money gave out and everything had to go. I hated to see Dad’s pictures go for so little, and Mother’s piano, too, but it had to be. I think it was the grief and shock and all that which wore Mother out. The doctor said she had no resistance, and when she took a heavy cold and had pneumonia she hadn’t the strength to fight against it.” Ellen tried to choke back her sobs.

“Don’t let’s talk about it,” said Miss Rindy herself, feeling an emotion she did not want to show, but she laid aside her knitting and patted Ellen’s hand furtively. “Just tell me where you went after all that happened.”

“First to one and then to another, but artists aren’t usually very well off, though they do manage to have such jolly times. They were all just as kind and generous as could be, especially Mr. Barstow, one of Dad’s best friends. He had a long talk with me before he sailed for Europe, and said I was not to worry, that he would hunt up some of my relatives, for it was only right that they should know I was—homeless.”

“He was quite right,” said Miss Rindy, again picking up her knitting. “I was fond of your mother, and I should be ashamed to have her daughter dependent upon strangers. You don’t have to call yourself homeless any more, you understand, for here you are, and here you be as long as I have a roof over me and a crust to share. I own this house and I have a little income. It will be close cutting, but we sha’n’t starve, I reckon. As for clothes, they don’t take as much stuff as they used to, that’s one comfort. You’re how old, Ellen?”

“I am just fifteen.”

“Well, you’re not very big, and won’t need trains even when you are grown up, so I reckon we won’t have to lay out much on dry-goods. I must start you to school first thing, and between school hours you can be learning useful things. Can you sew?”

“A little; I used to help Mother sometimes.”

“That’s something. Can you cook?”

“I can make toast, and cocoa, and fudge.”

“Cake?”

“No, we bought cake when we wanted it. We had no real stove, you know.”

“To be sure. Funny way of living, but never mind, you’re never too old to learn, and we’ll begin next Saturday on gingerbread. What about clothes? Have you enough to last a while?”

“Ye-es, I think so; not many black things, and I want to wear black.”

“So you shall, for a while anyhow. What isn’t black can be dyed.”

“But dyeing is expensive, isn’t it?”

“You don’t suppose for one minute that I’d send anything to a dyer’s when you can get a package of dye for ten cents? No, sir. When I want coloring done I do it myself.”

“Oh!”

“Yes, ‘Oh!’ I imagine you didn’t know that things could be dyed at home.”

“Yes, I do know, for lots of the women artists do it when they want draperies or costumes and such things. Mother never did because there was always so much else to do, and because it wouldn’t have been convenient.”

“We’ll unpack your trunk to-morrow and then we can tell what can be dyed. You can help me with the stirring and rinsing. What about your mother’s things?”

“They are in a trunk Mrs. Austin is keeping for me. Mrs. Austin was one of our good friends.”

“Better send for the trunk. No doubt there will be many things in it that you can make use of.”

“Oh, but—Mother’s things!” The tears rushed to Ellen’s eyes. “I—I couldn’t.”

“There, child, there. No doubt you feel that way now, but in a little while you will love to wear them; you’ll feel that she would like you to, and it will bring her nearer.”

“Do you—do you really think so?”

“Yes, I do. It may be hard at first, but you mustn’t be over-sentimental; it doesn’t do for poor folks like us, and you can’t afford to hoard away anything that will be of practical use to you. We will attend to your trunk first; meantime send for the other.”

So as soon as Ellen’s trunk arrived Miss Rindy applied herself to the task of going over its contents. Most of the pretty, gay little dresses, with a faded coat, were laid aside for dyeing, and the colored stockings put with them.

“These tan shoes can be made black easily,” decided Miss Rindy; “so can that light felt hat. I can reshape the hat over a bowl or a tin bucket. Let me see those gloves. I can dye the cotton ones, but I’m not so sure that I’d better undertake the kid; we’ll see about that later. Can you knit, Ellen?”

“Yes, when it’s straight going.”

“Then this evening you can rip up that yellow sweater. I’ll tie the worsted in hanks and dye it black, then I’ll show you how to knit it over and you’ll have a good sweater for school. Do the dresses all fit you?”

“Some of them I’ve outgrown; both those blue serges are too small.”

“Then we’ll rip them up, dye them together, and make a good dress of them that will last you as long as you need to wear black. Give me that piece of blue ribbon; it will do to go around your hat when it’s dyed. There now! I don’t see but you’re all fixed up, or will be when we get everything ready.”

Ellen was quite overcome by these suggestions of her exceedingly resourceful cousin. “You’re a perfect wonder, Cousin Rindy,” she said.

“Well, I never was placed in the bric-à-brac class, pretty but useless, and I hope you’ll not be.”

“I’ll never be the first,” returned Ellen with a smile, “and I don’t want to be the second.”

“It’s up to you,” returned Miss Rindy. “We’ll start on these things to-morrow, Ellen. If it should suddenly turn cold, you’ll need the coat and hat. Those stockings you have on are disgracefully faded, such a dirty green as they are. Haven’t you any other black ones?”

“I have a couple of pairs, but they are soiled and need mending.”

“Then get them out. Here, pile all those things on one chair. Don’t leave them scattered around till your room looks like a second-hand clothing shop. First thing to do is to wash out those stockings, and, while they are drying, you can run down to the drug store and get the dye. This evening the stockings will be dry and you can darn them. If you are to start to school on Monday, your wardrobe must be in some sort of shape.”

Under her cousin’s directions Ellen soon had the stockings washed and hung out; then she started forth to get the dye. “But, you know, I haven’t an idea where the store is,” she remarked as she paused at the door.

“You can’t miss it or anything else in this place,” Miss Rindy answered. “Just follow your nose and it will take you anywhere you want. Walk straight down the street till you come to the church, the white one, not the gray. It is just opposite the store, and the store is opposite the church; it’s the post-office, too. You can’t miss it. Now, run along.”

Ellen started off to make her first venture into the one long street of the drowsy old town. It was early November, and a mat of red and gold leaves covered the boardwalk, for the street was not paved. Houses, set rather far apart, stood each side the street. Most had gardens in front where a few late chrysanthemums and scarlet salvia brightened the borders. Some more thrifty households had vegetable plats in which long, dry blades rustled from shorn cornstalks, and purple cabbages squatted in rows farther along. The air was full of the tang of fallen leaves, of apples, wind-fallen, rotting on the ground. Once in a while, from some kitchen where pickling was going on, spicy odors were borne.

As Ellen entered the general store she noticed that it held a conglomeration of all sorts of goods. The drugs were on a row of shelves at the farther end of a long counter, neighboring the piles of gingham, flannelettes, and such dry-goods. Next came canned articles and groceries. These led the way to hardware, which followed shoes. At the extreme end of the store was the post-office. The middle of the store was occupied by such vegetables and fruits as were in season. In the glass cases were notions, candies, and stationery. The loft up-stairs was given up to crockery and house furnishings.

Ellen stood just inside the door for a moment and looked around. She had never seen just such a place in her life, and wondered how on earth the proprietors managed to keep track of such a mixed stock. There was no one in the store, but presently a voice from behind the post-office box called out, “I’ll be there in just a minute,” and before long a slim, dark-eyed little woman appeared. “He’s gone to the city,” she explained, “and I’m kind of short-handed, for the boy has gone out with the orders. What was it you wanted?”

“I want some black dye.”

“Who’s it for?”

“Miss Orinda Crump.”

“Oh, Rindy Crump. What’s she going to dye?”

“Several things.”

“Silk, cotton, wool, or mixed goods?”

“Why, all kinds, I think.”

“Then I’d better give you a package for each, and if she doesn’t need all, she can return what she doesn’t use. Kin of hers?”

“I’m her cousin.”

“Making her a visit?”

“Why, ye-es. I’m going to live with her.”

“You are? I did hear somebody say last night that a power of Rindy’s kinfolks came down yesterday. You don’t mean—— But never mind, I won’t ask any more questions. Rindy can tell me all about it. What did you say your name was?”

Ellen hadn’t said, but she gave the desired information.

“You don’t favor the Crumps,” continued Mrs. Perry; “none of them have red hair.”

“I’m like my father,” replied Ellen, tossing back her shining, copper-colored locks.