11,56 €

Mehr erfahren.

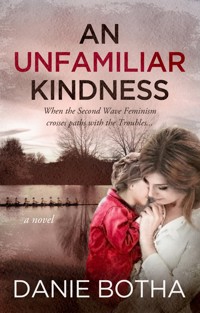

- Herausgeber: Charbellini Press

- Serie: An Unfamiliar Kindness mini-series

- Sprache: Englisch

When the Second Wave Feminism crosses paths with The Troubles . . .

Mistaking gratitude for love comes at a price.

In 1971, Oxford student Emilee Stephens marches with the just-formed Women’s Liberation Movement. She meets Connor O’Hannigan, an intriguing sympathizer who harbors more secrets than the reason he’s at the march.

Despite her friends’ repeated warnings—and even hints that he may be in the IRA—Emilee falls for Connor when he saves her life in a kayaking accident.

The two marry and have a daughter, Caitlynn Aine. On the child’s third birthday, daughter and father disappear, leaving only an abandoned car and a small red jacket behind.

Decades pass—until Emilee receives a handwritten letter from her presumed-dead former husband.

An Unfamiliar Kindness asks an unanswerable question: how much does love cost?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 417

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

An Unfamiliar Kindness

Danie Botha

Contents

Also By Danie Botha

Dedication

Author’s note:

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Epilogue

Final notes

Acknowledgments

References

Also By Danie Botha

Be Silent

Be Good

Maxime

Young Maxime

An Unfamiliar Kindness

Copyright © 2018 Danie Botha

All rights reserved

This book was published under Charbellini Press.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without the express permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews.

This novel is a work of fiction. All the characters and most of the situations are fictitious and a product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

https://www.daniebotha.com

Published in the United States by Charbellini Press

ISBN-13: 9780995174870 paperback

ISBN-10: 0995174870

ISBN: 978-0-9951748-8-7

Created with Vellum

For Charlize and Clara-Li

Author’s Note:

Until the late 1970s, connections between Britain, Europe, and South Africa were maintained by sea for passengers, cargo, and mail. The large ships completed the fourteen-day journey with considerable ease. One such liner was the Windsor Castle, a British Royal Mail Ship (RMS), which completed the journey between Southampton and Cape Town on a regular basis, always departing on a Thursday at 4 p.m. Only during the latter part of the 1970s did the arrival of the jumbo jet make air travel not only faster but also cheaper than ocean liners.

“The Troubles” refers to the thirty-year period of conflict from 1968 to 1998 between elements of Northern Ireland’s Irish Nationalist community (mainly self-identified as Irish and Catholic) and its Unionist community (mainly self-identified as British and Protestant). The goal of the former was to end British rule in Northern Ireland and reunite Ireland and create an Irish Republic. During this time, more than 3,500 civilians were killed.

The Women’s Liberation Movement in the UK that kicked off in early 1970 was a second-wave feminist movement, which followed the suffrage campaign of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It pushed hard to improve the conditions and quality of life in general for women. It succeeded in getting several laws passed, such as the Equal Pay Act in 1970, the Sex Discrimination Act in 1975, and the Domestic Violence Act in 1976.

Even though An Unfamiliar Kindness is woven around these historical facts, it remains a work of fiction, and all the characters and most of the incidents are imaginary and bear no reference to individuals alive or dead.

Prologue

The letter. Oxford, UK. 29 July 2000.

Emilee was afraid, not of dying, but of picking up her mail.

This had to stop, she realized—her being so terrified. Each time the heaviness choked the life from her. All these years—all the therapy sessions—wasted.

Friday afternoons became a calculated dance, rehearsed to precision. Only in the safety of her apartment, the doors locked, two fingers of Dún Léire on the rocks later—would she sort through the postal pieces, berating herself for being such a coward.

And the therapist claimed I’d outgrow my angst. Well, she knows nothing.

It started as a game. He was smart. Serious. A complex man. She loved the challenge, in spite of the intimidation; the elaborate daily test. The changes were subtle, so slight she didn’t notice. Her insecurity grew under his ridicule. It turned into a maelstrom, from where there soon was no escape. And, when he got ill, it blossomed into full-scale dread—of living with an unpredictable man. From the mountaintops he plunged into valleys of desolation, the momentum hauling her along. She loved him and yet learned to fear for Caitlynn and herself when he became aggressive, vindictive. Then, one night, they disappeared; without word, without warning. No last kiss.

The search was a stillbirth from the start. Caitie’s red jacket was discovered a week later a mile downstream. Nothing else. How does a heart heal when it is denied farewell, denied closure, even a burial? It was three years later when Emilee filed for an annulment. For the declarations of presumed death, she had to wait seven.

She remained hopeful to receive word—a letter, a notice in a newspaper, a sign—even a body.

There was nothing.

When the official documents arrived, after seven years of waiting, seven years of hoping, she could begin her grieving.

Emilee surprised even herself as she bolted away from the counter, her face drained. The high stool crashed over, and her mail scattered as she glanced around the room. Shivering, she shook her hand with the letter as if to free itself of the calamity that had entered her house and from the horror that had attached itself to her fingers: a handwritten envelope with no return address.

They were dead. Connor and Caitie are dead. It was official. The courts had confirmed that all those many years ago. In the end, she believed it to be so.

And even if that were no longer the case, how could he have known my mailing address? If he found my address, then he knows where I live. Why an old-fashioned letter? He must be outside, watching the house. She shuddered. But he’s dead, Emilee. And Caitie? He must know what happened.

She scrutinized the letter under the glaring spotlights of her breakfast nook. It is him. The way he curled his n’s. He must have a tremor now. The post office stamp was legible: 27 July, 2000. Unmistakable. It had been mailed in Slough. So he went back. Still clinging to the unopened letter, she grabbed her cell phone and darted through the house, again checking the front door.

Emilee slipped the Yale lock into place one more time and turned the key in the second lock, then raced to the back for the kitchen door and turned the key one more time, then through to the living room where she yanked the sliding door open and stepped onto the small, open-sided porch. She glanced around then jumped down three brick steps. She paid her only row of blooming roses little attention as she dashed toward the garden gate on the side of the house. It was a wooden contraption built from split poles—like the fence, six-foot high—and covered by a trumpet creeper over its entire length. The creeper was late that year with flowering. The padlock was in place, and she gave it a confirmatory tug.

Her heart skipped another beat. The water. He can come along the water, along with the Castle Mill stream!

She raced through her backyard toward the twenty-foot stretch of dock, which had been built flush with the riverbank. She tried to tiptoe to the dock’s edge, but her momentum made her do a butterfly dance not to end up in the water. Once she regained her balance, she peered up and down the stream, cupping her hand against the glare. There was no traffic on the canal, not even a water snake to disturb its surface. It was too quiet for that time of the afternoon. She cocked her head. Water lapped against the undersides of the wooden dock. She inhaled the reassuring smell of water grass, rotting wood, and stale water.

Something yellow caught her eyes: the tip of her kayak, safely tucked in along the cast-iron fence to the side of the property, underneath a long, rectangular black tarpaulin she had strung to protect it.

She could not recall being in such a panic—not since she had moved back here to Rewley Road in 1983. At first, she had rented, but then she bought the place. She had never been afraid—not to this extent, not since they disappeared. Not since the courts had sent her the certificates.

Dare I hope again? Caitie would have turned twenty-seven in May.

She stepped through the patio door on her way back and heard thumping on her garden gate. She jumped. Someone had called her name.

She paused before slamming the door closed behind her with a scream, only to open it again and jut her head out. “Francois?”

The thumping was more assertive. “Emilee!”

“Hold on. I’m getting the key!”

She fumbled in the kitchen. The key was not hanging on its usual little hook. She dropped the letter and hurried outside. She could see narrow slices of her friend through the slits in the gate. “I’m sorry, but I can’t seem to find the key.” She stopped to catch her breath. “Come around to the front door.”

“What’s going on?”

Running back toward the house, Emilee hollered, “Try the front door!” She slammed the patio door shut and locked it, scooped the letter from the floor, and made for the front entrance. Why could Francois not have phoned me like other civilized people, to say he was outside? The poor idiot. His head is still in Africa.

She jerked the Yale lock back and turned the second key, swung the heavy door open, and grabbed her startled guest by his jacket. She dragged him inside, kicked the door shut, slipped the Yale back in place, and turned the key. She spun around and took his face in her hands and kissed him smack on the lips. His face was one big frown.

“Francois.”

Francois Moolman took hold of Emilee’s shoulders as tears ran down her cheeks. He tried to dry them with his thumbs, stroking upward on each cheek, but failed. He inhaled her fear.

He hesitated, then kissed her pale lips. “What is wrong?”

“You won’t understand, this . . . this . . . .” She shook the condemning letter, which had grown to her skin.

He pulled her closer when she gave a sob and hugged her, her tremors shaking them both. “When I spoke to you earlier today, everything seemed fine.”

“It was fine. I received, or rather discovered, this letter only minutes ago among my stack of mail.” Emilee stuffed the letter into his hand.

And everyone thought I was mad for having this obsession about picking up my mail.

He broke the embrace and pulled her behind him into the house. “You don’t mind if we go in and perhaps sit down?”

He plopped onto her couch and studied the letter. “Isn’t it amazing that there are still people writing letters by hand and then with an ink cartridge?” He began reading aloud.

“Mrs. Emilee O’Hannigan.” Francois glanced at her. “You never told me your married name. I much preferred Emilee Stephens.” He turned the envelope over several times. “This was written by an individual who is sure of himself, or, perhaps not. The writing is a bit unsteady. It was written with a fountain pen, was mailed two days ago in Slough, and it has no return address.”

Francois held out his hand. “Come sit, Emilee O’Hannigan. Please.”

She took the letter from him as she sat down, their thighs touching, but she continued shaking. “Thank you, Mr. Sherlock, but I already know all that.” She struggled not to smile through her tears.

He studied her eyes, the face of the woman he had put on a plane in Windhoek, Namibia, four months ago. She had then seemed at peace with herself and her world.

“You plucked me through your front door like a Navy SEAL on a mission and then locked everything in a panic. Why are you so terrified?”

“This letter was written by Connor O’Hannigan.” Emilee took several breaths. “But he’s dead, or rather, was dead. I was married to him for four years during the seventies. He was involved with the Unions and The Troubles in the North. His involvement was much deeper than I had ever suspected. Then he disappeared one day, with our daughter. They were declared deceased by the courts in nineteen eighty-three, after seven years of hoping and waiting.”

“You had a girl?”

Emilee nodded.

“What . . . has he done to you?”

“It’s not that simple.”

“Did he hurt you?”

She shook her head but avoided his eyes.

“He must have,” Francois insisted, lifting her chin.

“When he got angry, which was often, he would break things, but he never hit me,” she whispered. “Although, he taught me, taught us, what fear was. He was a master.”

1

The RMS Windsor Castle. Cape Town, South Africa. 7 December 1969.

Emilee tightened her iron-grip on her friend’s hand and elbowed their path open to a spot next to the railing, apologizing as they went. She bestowed a sweet smile on everyone who frowned on their uncivil pushing to get to where they could have an unobstructed view of the dock far beneath. She was determined to make visual contact with her family before their ship sailed. Taken aback by their boldness, young and old, male and female, found it impossible not to take a step back to allow the two girls thoroughfare.

Caroline Washington had little control over her blushing, which only intensified as they approached the railing. She loved her friend but was equally exasperated by her forwardness. Her free arm was engaged in keeping herself decent as she smoothed and held down the hem of her summer dress that took flight in the breeze. Wearing the miniskirt dresses was Emilee’s idea. “Something cool and complimentary for our departure,” she had said.

Still attached to Emilee’s hand, she whispered, “That was so embarrassing.”

Emilee only laughed. “No, it wasn’t. There they are!” She pointed at her parents, brothers, and Caroline’s family, who stood huddled together on A-berth, waiting on the two girls to appear.

Emilee took a step back from the railing as the subtle stench of spilled sewage, salt water, dead fish, and ship’s oil shot up at them. Far below, gentle waves washed against the steel hull.

Their families heard them calling and answered their beckoning. Everyone waved. The moment they had dreaded and dreamed about had arrived.

The wave of hands intensified. Some waved with handkerchiefs, shouting endearments as the PA system behind the girls warned, “The ship is sailing.” The horn sounded. Dockworkers called in warning. Seagulls screeched excitedly as they dipped toward the water.

As the horn sounded a second time, the screws started turning. The bow—in no apparent hurry—righted in the direction of the open sea. Later, it would point at Southampton. The people on the wharf-side grew smaller, the separation taking place in slow motion until they were beyond hearing distance. Neither party had the heart to cease waving, not even when infinite specks were all that remained of them. Emilee clung to her handkerchief, waving, refusing to concede.

One by one the passengers left the railing in search of their cabins, but the two friends held fast, unwilling to say their final goodbyes. Wrapped in its cloud-blanket, Table Mountain towered behind Cape Town as the RMS Windsor Castle left port.

Emilee squeezed her friend’s hand, leaned against her, and whispered a last goodbye to Cape Town and good old Africa. Caroline repeated the farewell and wrapped her arms around her friend’s slim shoulders to slow her shaking.

She pondered whether they would ever see their folks again, or their country, and whether that would happen before they were both old and senile.

Together they swayed with the roll of the ship, leaning into the breeze.

They remained there until the mountain and the continent faded into the sea and their tear-streaked faces had dried.

Their haven for the ten-day journey was a two-berth cabin, number 54, in Tourist Class. Since it consisted of two bunk beds, they had to toss a coin on Emilee’s insistence, “in order to be fair.” Caroline spun the coin and Emilee called it. Emilee chose the top bunk.

Except for a single red chair, everything in the cabin was mint green.

Emilee immediately responded, “It’s hideous. It looks like bile!”

“Bile is yellow. This is called mint, and the bedspreads have beautiful hibiscuses. They’re gorgeous and match the chair.”

“It’s still hideous,” Emilee said, giving her final verdict. “Our cabin smells of abandoned rugby boots too.”

As she bent forward and stretched out on the hibiscus-print spread, Caroline stared at her friend of five years, baffled by her random outbursts of cynicism. She closed her eyes and imagined smelling the flowers. Rugby boots. They had both graduated three weeks earlier from Wynberg Girls High in Cape Town and were on their way to Oxford, where they would study with scholarships. She was so proud of them both—they had worked hard for this, to get accepted—and yet so afraid. England had seemed all safe and secure and not far at all on the map.

But just now, when Table Mountain finally dropped off behind the horizon, the ten long days on the open sea sunk in. It was quite disconcerting. They were scheduled to berth in Southampton on the seventeenth, with their interviews for college placement, as per special arrangement, at 9 a.m. on Friday the nineteenth. Her hopes were to study law, and Emilee was obsessed with immersing herself in English literature and modern languages.

Emilee bounced to the floor. “Come on, Carrie. Enough of this self-inflicted cabin-arrest. I’m not waiting until suppertime. Let’s go find something edible.”

They locked the door and bolted down the hallway as Emilee bellowed, “Last one to reach the Promenade deck is an old maid!” They ran neck-to-neck until Emilee overtook her friend as they rounded the corner, where they crashed into a crewmember, sending them all careening to the floor. The poor man went down without so much as a squeak.

Caroline had seldom seen Emilee crimson and in search of words. She was stuttering as they picked themselves up and straightened their clothes. The young man had gathered the small stack of papers he was carrying and pushed his fingers through his hair before he put his cap back on. He glared at Emilee.

“Is there an emergency that the captain should know about, Miss?” he managed with a straight face.

“No . . . not exactly,” Emilee stuttered, catching her breath. “We were being silly. I’m so sorry.”

“Not at all. Do you play rugby, Miss? That was a brilliant tackle.”

Emilee laughed and flushed. She was not blind. He was striking—a virile young man. He smelled of shaving cream. “You’re making fun of me, sir. Please forgive us.”

“I’m afraid I can’t. I’ll have to report you to the First Officer on deck. No running is allowed on this vessel.”

“Excuse me? That’s a joke, right?” Emilee said.

“It is not. This is a Royal Mail Ship. We discourage any frivolity during the journey due to the precious cargo in the hull. Your name, Miss?” The man took a small notebook and pen from his pocket but failed to hide his grin.

Emilee groaned as she grabbed Caroline’s hand. “Come, Carrie! This man is not accepting our apology and takes us for fools.” She scrutinized his nametag. “Excuse us, Mr. Harding.” She spun around, no longer embarrassed but furious.

He capitulated immediately and called after them, “Ladies, I’m sorry! I’ve been an ass—it was unpardonable. Please allow me to make it up to you.”

Emilee turned back. “Pardon me, Mr. Harding. First you refuse to accept my apology, and the next moment you make a pass at me. I would say that is unpardonable. Come, Caroline. Perhaps we should go find the First Officer on deck.”

Mr. Harding remained only one step behind them as they went up the staircase. “Please accept my apology, Miss. But I still don’t know your name.”

“Perhaps it is better that way, Mr. Harding.” Emilee hollered, “We prefer anonymity,” and they ran off toward the dining hall.

2

At sea. 8 December, 1969

It was lunch hour the following day before Douglas Harding had success in locating the two young ladies from cabin 54 who had run him over. He chastised himself for not being able to extract the anonymous one’s name from her before he had to sound the retreat. He stood behind the buffet tables armed with a small stack of menus, which he had reprinted late that morning.

He bided his time. He could not afford another fumble with the redhead. There were over eight hundred passengers on this vessel, with scores of young ladies, and he had to choose these two. If he caught him here, his boss in the printing shop would demand his head.

He approached their table and leaned in next to Caroline’s chair. “Excuse me, Miss Caroline, I hope I’m not too late. I printed a couple of fresh menus for your table. I was hoping . . . .” He offered the blushing Caroline two of the menus.

“Thank you, Mr. Harding,” Caroline stammered.

Emilee leaned forward and hissed, “How did you find us? Are you a stalker?”

“No, Miss,” Douglas said. “I only brought you those, as well as this,” and he took a folded sheet from his back pocket. “Perhaps, if you missed the daily news-sheet.”

Caroline slapped her friend’s arm, “Stop it, Emilee. It’s a peace offering.”

“Stalker,” Emilee insisted.

He ignored her comment. “Thank you, Miss Caroline. I have to go. Have a pleasant meal. Please excuse me, Miss Emilee, Miss Caroline.” He hesitated, took the news-sheet from Caroline, scribbled on it, then handed it back to Emilee, bowed, and took his leave.

“What did he write?” Caroline cried as she tried to take the news-sheet, but Emilee pinned it down on the white tablecloth.

Miss’s E & C, please meet me at the entrance to the smoking room at 4 p.m., aft side. Douglas Harding.

“He likes you,” Caroline purred as her friend let go of the sheet and she inhaled the fresh printer’s ink. She closed her eyes.

“Oh please, he’s a pip-squeak who stalks us.” Emilee leaned back in her chair as they waited for their order. “I think we should rather socialize with the engineers or radio operators. That sounds so much more exciting and sophisticated than printing-shop assistant.”

Caroline gasped, “You are a snob.”

“Or better still,” Emilee laughed, “what about the sonar operator?”

“Be careful what you beg for,” Caroline said. “The sonar guy might be a blubber of a sailor with a stubble beard and missing teeth. If you wish to meet the upper class, we’ll have to hang out in the dance hall every night, or go on hourly excursions with the captain—if you can convince him.”

As soon as they left the dining hall, Emilee made them search for two unoccupied deck chairs. “Please let me lie down—my sea legs feel all wobbly. I’m not used to this constant heaving.” She dropped down on the first open canvas chair. Her complexion was similar to the mint color of their cabin.

Caroline was easy to be alarmed. “Shouldn’t we rather go to the hospital? Let the ship surgeon attend to you.”

“No . . . no doctor. It will pass. Let’s rest for a bit.”

Emilee broke the silence after two minutes. “Aft. Is that at the rear, the stern?”

Caroline laughed. “It’s the rear. He’s a stalker, remember? Now you want to go and meet with the man.”

“He’s only a boy. It will be bad manners if we don’t show up.”

“A beautiful boy. He looks twenty, though,” Caroline mused.

“Nineteen, max. He has such a weird accent.”

“He’s British, silly. They must think we speak funny.” She turned on her side facing her friend. “Somebody’s smitten.”

Emilee snapped upright. “I feel better already. Smitten? Who’s silly now? Let’s grab our swimming gear and do laps in the pool.”

Their hair was still damp from the swim as they hovered outside, close to the stern entrance to the smoking room, leaning against the outside railing, trying desperately to look old enough to hang around a bar facility.

Douglas Harding was on time, to the second, and walked over with a wide grin. He had changed out of his uniform. “Miss Emilee, Miss Caroline, I am honored—you both came.”

“We didn’t want to hurt your feelings, Mr. Harding,” Emilee said. “Please, can you drop this Miss thing. We are not princesses.” She curtsied.

“Shame on you!” Caroline chided.

“I see milady mocks me,” Douglas said.

“Well, stop acting like a fool. And what’s it with the smoking room? None of us smoke.”

“Neither do I.”

“So, is this really the only place on the ship where you can meet a young lady?” Emilee asked.

Caroline tried to put her hand over her friend’s mouth.

“Very few people actually smoke inside,” Douglas said. “Children are not allowed in here, so there’s no one who can run you over, and besides, they have a decent bar. You’ll love it. Both of you are eighteen, aren’t you?”

Emilee blushed. “Touché, Mr. Harding. Yes, we’re over age. Sorry for being such a bitchy female.” She held her hand, which he took and squeezed.

“That’s a contradiction of terms, but you’re forgiven,” Douglas said. “Let’s go inside.”

Fresh-poured liquor, tobacco smoke, and leather upholstery greeted them as the three found seats at the far side of the bar counter. The two girls got lost in studying the cocktail menu. Caroline bumped Emilee’s elbow, whispering, “What are you going to order?”

“Tequila sunrise.”

“It sounds like a breakfast drink.”

Douglas laughed. “It would be wiser not to start with that in the morning.”

“Well, it’s healthy. Got tons of orange juice in it,” Emilee replied.

Caroline continued whispering, “You never drink. Where did you learn all this about cocktails?”

“I did some research before we came, in the school library.”

“You learned about mixing cocktails in our school library?”

“One only needs to know where to look.”

They were thirsty from the swim, and Emilee finished her first sunrise with three gulps. She immediately ordered a second one and downed it on the spot. Caroline sipped on her first one with caution. Douglas said nothing as he nursed his drink, his hooded eyes resting on them.

“Wow! I can feel the orange juice surging through my veins,” Emilee said.

Douglas raised his brow, and Caroline touched her hand. “That’s not the orange juice you’re feeling. Slow down.”

Emilee bubbled over, “Oh no, Carrie, I am filling up with vitamin C,” and she laughed with unfamiliar abandon.

They sipped in silence for several minutes, but as soon as the tequila and vitamin C found equilibrium inside her, Emilee turned in her high seat, all sweet and nice. “What exactly are you doing on the Windsor Castle, Douglas Harding?”

“I chaperone unescorted young ladies from the Cape of Good Hope all the way to Southampton and deliver them in one piece to the doorstep of her Royal Majesty.”

Emilee snorted in her drink. “Douglas, you Philistine! Not only are you a stalker, you are a charlatan.” She turned toward Caroline. “See why I need to be hard on him?”

Douglas laughed and clinked their glasses. “I’ve been employed on this Royal Mail Ship for the past twelve months. I started as a cleaner in the dining hall, which I didn’t enjoy. I got to meet all the passengers, but they all, especially the young ladies, took me as a fool because of my low status. I transferred to the printing shop, where I am now the first assistant, my day job, and I love it.”

“And first printing assistant has status?” Emilee asked.

He pulled up his shoulders. “I enjoy it.”

“And what is your other job?” Caroline asked.

“Oh, that is my chaperone portfolio, my extracurricular activity, from after work till I start again the next morning. But I don’t charge for the service. It’s free.”

Both girls turned scarlet.

“That’s not what I meant!”

Emilee jumped off her chair, “We’ve heard enough. Carrie, let’s go. He’s indeed a charlatan. Thanks for the drinks, Mr. Harding. Please excuse us.” Emilee took Caroline by the arm and they made for the exit.

Douglas was quicker and bolted ahead of them. “Ladies, that was unfair! I said nothing improper. I was pulling your legs. You act as if I run an undercover white slave-trade business on this mail liner.”

Emilee pouted her lips. “For all we know, you do.”

“Let’s at least finish our drinks,” he pleaded.

“My friend feels I’ve had enough,” Emilee said.

“Remember that it’s not water, and sip it slower,” he said.

The girls took their time to return to their drinks at the bar counter and slipped back onto their seats, eying their companion with suspicion, not touching their cocktails.

He threw his arms up in mock surrender. “Why are you guys glaring at me like that?”

Emilee jumped up again, this time with her drink in hand. “There’s an open table in the back. Come along.”

Once they sat down, she downed her third drink with little hesitation, hiccupped twice, and giggled. She leaned forward in an unhurried fashion and murmured, “Douglas Harding, did you think just because we wear bell-bottom jeans and our hair all long and wavy that you could bring us here, get us all tipsy, and then make love to us?”

Caroline gasped. Douglas choked on his drink.

“Make love?” he whispered, still coughing.

“Yes, Douglas, have intercourse with us—one after the other. I can see you are young, fit, and trim. You could do that.”

Douglas Harding was pale when he stood up, keeping his voice down. “Is that what you want?”

“No, Douglas,” Emilee said, “that’s what you were hoping for. Two for the trouble of one.”

Although she had temporarily lost her tact and sensibility, she was still able to read his expression, witnessing the extent of his turmoil. She immediately regretted her words. Not once since they’d met (even in the most awkward fashion on the hallway floor when she’d run him over) had she found him staring at her in a gawking or lusting fashion, undressing her with his eyes, as many of the other males on the vessel had done with both her and Caroline. Although, he had openly demonstrated an interest in her, which was, she realized now, an appreciation of her unbound spirit, of her fearless honesty.

His eyes and mouth showed the unexpected hurt: a mixture of shock and disappointment, but also a declaration of hope that he was not wrong in his initial assessment of her character. Those fleeting expressions confirmed his noble intent: that he was innocent of what she had accused him—the betrayal was all hers.

“Miss Emilee, you’re not used to alcohol, to cocktails for that matter, and definitely not on an empty stomach.” Douglas’s voice was hushed. “You’re probably a little drunk. Why would I want to make love to you? Sorry, that came out wrong. You are both alluring females, two exceptionally gifted individuals, and I was . . . .” He blushed, coughed, and continued.

“A man can dream—but that was not my intention. I thought you were different from all the other girls on the ship who only care about fancy nails and designer clothes and five-course meals and copulating. They don’t make love—they have nothing between their ears. I thought you were of a class apart. You have such a fresh and effervescent spirit. I was wrong. Excuse me, ladies.”

He bowed and stormed from the smoking room.

3

A storm in the Atlantic Ocean. 8 December 1969

Caroline bolted upright and implored her friend to meet her eyes. “I don’t need to tell you—that was low. Shameful. I give you a formal time-out. I’m going for a long walk outside. Don’t try and follow me. I do not want to see you, and I do not want to talk to you. I only want to see you once you’re truly sorry.”

Emilee jumped up, her eyes wet. “Carrie, don’t go . . . I’m sorry . . . .”

“No, you’re not! Sorry comes too easy for you. I am extremely upset with you. You’re more than a little drunk. Ask the barman to help you with a black coffee.” She marched out without looking back.

Caroline followed the railing toward the stern, glad to escape the stale confines of the smoke room. The wind gusted round the superstructure, taking her by surprise, billowing her clothes; it forced her to cling to the railing. This stupid long hair. She lurched into a doorway, pulled the hair out of her face, and knotted it into a ponytail before grabbing the railing again. Just imagine if I had a dress and platform shoes on. I’ll show Emilee. I’ll finish my walk. I need some distance from her. She went down a set of stairs and had difficulty telling where the dark sea ended and where the gray skies began.

She wasn’t certain for whom she felt the most sympathy: for Douglas, for herself, or for Emilee. She hauled herself along, struggled against the wind, and moved with the roll of the ship. And they boasted about those stabilizers down below!

Only during their last year in Waterloo House, the hostel at Wynberg Girls High, did they receive half a glass of wine each, on three separate occasions, and once at a wedding, when they had champagne. She realized now how pitiful and inadequate the parental and adult educators’ guidance had been in all things men: falling in love, relationships, marriage, making love . . . contraception.

The word sex was seldom used. It was hushed—referred to but seldom uttered. The same went for smoking, alcohol, and recreational drugs, believing it would suffice to inform them, “Ladies of good upbringing abstained from such things, since it destroys lives.” As if that would be good enough.

Emilee’s parents still worked in the Caprivi in Namibia, so she had spent every weekend in the hostel, except for the few compulsory weekends out, when she would stay with Caroline’s folks.

Limited. That was the extent of their knowledge and exposure to alcohol—and to boys. The few times she had tumbled around with them, the farthest they’d ever got was to fondle her breasts. She never allowed their hands down there.

She liked the Harding boy. He was more than sweet. To use his own word, he was different. In spite of the unruly wind that tugged at her, she found herself glowing as she thought about the first printing assistant on the Windsor Castle. He wasn’t a stalker, only a tenacious young man. She liked that. She was so ready to fall in love with such a man—someone who cared.

She was certain Douglas had taken the trouble to print the extra menus for their sole benefit, at great risk to himself, if only to impress them. She could still smell the fresh printers’ ink when he handed her the menus. Their fingers had touched for the briefest of moments, sending a current through her—it gave her goose bumps all over again.

Wake up, Caroline! He did it for your friend, before he realized she had a two-forked tongue. Now he will have nothing to do with either of us.We’ve barely been on this liner for twenty-four hours and already we’ve sunk to the bottom of the popularity list.

In the five minutes she had been outside, the wind had increased in force, and she had to pay attention and guard each step. Every second step, a spray of seawater rained down on her. She licked her lips. The saltwater stung. Gone was the nauseating odor of the harbor and docks in Cape Town.

Her path became slippery fast. The railing and deck were as if coated with soap. She lost her footing once. Then a second time. Emilee will be the death of me. But I am not ready to go back. She passed a pair of deckhands dressed in orange oilskins. They were tying down some of the big ropes on deck and securing everything around it. They mock-saluted her, pointed toward the ominous grayness above them, then pointed below. They yelled something at her. The wind stole their words.

“Excuse me?” she hollered back.

“Back! . . . You should turn back . . . Inside . . . .” She lip-read.

One of them shuffled across and was slammed into the railing next to her. Once he regained his balance, he grasped her by her upper arm. She was surprised by his immediacy and physicality and tried to yank her arm free. He smiled at her but held tight and yelled close to her ear. She smelled his hot breath and inhaled his oilskins and sweating torso. His lips brushed her ear. “Storm coming . . . Let me help you . . . This wind . . . Not your friend.”

He refused to let go of her arm and helped her work her way back, both of them clinging to the railing until they reached an outside door where she could slip in. He held the door steady against the wind and tugged her inside. She was surprised how immediately quiet it was in the hallway—safe and warm and dry.

“You’ll be fine now, Miss. Just follow the hallway all the way to the center of the vessel.”

“Thank you,” Caroline piped.

The sailor grinned at her, gave a half-salute, and, with an almost inaudible “Ma’am,” disappeared back into the storm. She pushed the door tight behind him.

Caroline leaned against the steel bulkhead to catch her breath. She was cold. Too bad about the wet blouse. I am not returning to our cabin. I’m not ready to face Emilee.

Setting off at a brisk pace, she hoped to warm herself with the walk but had to slow down. Like-minded passengers, all forced indoors by the storm, congested the hallways and stairs. The temptation for a bite became overwhelming when the aroma of fresh bread wafted from the gulley. It would have to wait until Operation Bridge is completed.

She rubbed her arms as she clambered the stairs and waited outside the door, shivering, peering inside.

Most of the bridge was visible. Officers and crew moved about with purpose, adjusting instruments and devices. No one noticed her. The glow of embarrassment crept up her neck. What were you thinking, Miss Washington? That you’re still an eight-year-old whom the captain will show around as a treat?

As she turned to leave, the door slid open and a man asked, “Can I help you, Miss?”

She spun around, her face glowing. This man is even more handsome than Mr. Harding. The arctic white uniform suited him. He was too young to be the captain—perhaps one day.

“Miss?”

“Oh yes, I . . . wanted to see the bridge.”

He hesitated, and the hint of a smile appeared as he stood back. “Sure, but you won’t be able to stay long. With the storm brewing, things are hectic around here. By the way, I am the third radio operator.” He gave her an amused look over. “It seems you have already tasted the tail end of the storm?”

She touched her wet hair and followed his gaze, regretting having chosen a white silk blouse that morning. Her nipples strained dark against the now-transparent, damp fabric. She clasped her arms across her chest and met his eyes until he looked away with a smirk, then followed him around the bridge, not hearing a single word he said. She prayed the churning sea would swallow her.

The trance only broke when he introduced her to the helmsman, who asked, “Would you like to spin the wheel, Miss?”

Mesmerized, she nodded and took hold of the large wheel, clutching it in a death grip. “Does this steer the ship?”

“Indeed, ma’am. Why don’t you relax your grip and give it a spin?”

“Spin it?”

“Yes, ma’am.” He showed her and she spun it.

Emilee would never believe that she had steered their colossal vessel during the storm. The third RO then showed her the intricacies of the radiotelephone, the gyro compass, and the radar monitor, as well as the functions of the multitude of dials against the one wall, but she was still navigating the RMS Windsor Castle through a storm in the Atlantic, off the coast of South West Africa, with a crew of 475 and some 821 passengers depending on her—Captain Caroline Washington—set on a course, north by northwest.

4

Doing penance.

The act of penance should not be undervalued, my child. Caroline recalled her grandmother’s words of last summer when they kneaded dough side by side in her kitchen. Then she had added, But the punishment should not be worse than the transgression, and never throw away the key.

Thank you, Ouma, for making me feel guilty.

Caroline had returned to their cabin, finding it empty. She rushed through a shower and changed into dry clothes. Miss Emilee is playing the martyr game, forcing me to go look for her.

She found Emilee sitting at a different table, in the corner of the smoking room, with three empty coffee cups in front of her. Emilee cringed and whimpered—a pathetic mess.

“What are you still doing here?”

“I’m doing penance,” was Emilee’s meek response.

“By hiding in a bar, drinking black coffee?” Caroline squeezed her friend’s shoulder only to jerk her arm away. “You’re drenched. Why did you go into the storm?”

Emilee’s shoulders shook as she glanced at her friend, her hand clasped over her mouth to silence her sobs. She shivered uncontrollably.

“Poor thing.” Caroline swooped in and cradled her friend, pulling her upright. “What happened? Let’s get you out of these wet clothes.”

She gripped Emilee’s shoulders and pulled her along, waving at the barman as they left.

“No need to cry. Douglas will survive the insult—he’s a big boy. Enough of this self-pity. You need a warm shower.”

Emilee was inconsolable as Caroline steered her from the aft deck inside and down hallway after hallway.

“Why did you follow me on deck?”

Emilee shook her head, trying to catch her breath. “I tried to get away from this man in the bar. I ordered a fourth sunrise after you left when this asshole joined me.”

“Why didn’t you call the barman?”

“I was embarrassed. We were both a little drunk. He was witty when he sat down, but then he started gawking down my shirt, making all kinds of vulgar suggestions.”

Caroline unlocked their cabin door, pulled her shivering friend inside, kicked the door closed, and peeled Emilee’s wet clothes from her.

Emilee wept louder as she allowed her friend to steer her into the soon-steaming shower, her teeth chattering. “I ran off. I couldn’t think clear . . . just to get away from him.”

“Here, take the shampoo.” Caroline passed the container around the shower curtain. She averted her eyes. She had to maintain an illusion of modesty. It was irrelevant that she had seen her friend unclothed before and that she had undressed her now.

“The bastard followed me onto deck and then groped me.”

“Didn’t you cry for help?”

Steamed filled the small room. Emilee poked her head around the curtain. “You were outside—it was useless. The storm gave him perfect cover.” She laughed through her sobs. “But I hit him.”

“That’s my girl!”

“He held on and fondled my—”

“Did he touch . . . ?”

Emilee yanked the curtain open for her friend to see.

Caroline gasped. Her friend’s chest was nine inches from her face. Both nipples were engorged and sienna-red from the steaming water. She had always been jealous of her friend’s perfect bosom—not too big, not too small. Two flawless peaks. Bruises the shape of deft fingers marred the left globe.

“The bastard!” Caroline whispered.

“He wouldn’t let go. I hit him again. He was so strong. Held me from behind, kissed my neck, and shoved his hand inside my jeans. He hollered something that sounded like ‘teach you a lesson.’”

Emilee spun back into the shower, her chest heaving as she let the curtain fall in place. She sobbed louder behind the plastic drape.

“Did he . . . did he manage . . . ?”

“The ship rolled and caught him off balance. That’s when I struck him a third time, this time between his legs, and shoved him into the railing. I escaped and raced back to the smoke room.”

“He didn’t go overboard?”

Emilee shook her head. “He was down on his knees when I left him.”

“Will you recognize him? Was he a passenger or crew member?”

Emilee turned the water off, stepped out, and allowed Caroline to wrap a towel around her. She shook her head and whispered, “I don’t know. He had civilian clothes on . . . I think.”

Once Emilee was dressed, Caroline made her sit down in their only chair, grabbed a second towel, and rubbed her hair down. “The scoundrel. We’ll hunt him down. Douglas must help us. We’ll go see the Captain. He can—”

“The Captain will laugh at me. I was drunk.”

“Drunk doesn’t mean you said yes.”

Emilee took the towel and faced her friend. “I was such a fool—baring my inexperience with liquor for the whole world to witness. I embarrassed you, my dearest friend. I must have mortally wounded Douglas Harding. And I became an easy prey for that drunken jerk. I’m certain Douglas never wants to see me or speak to me again.”

“Nonsense. It was a misunderstanding. I told you, he’s a big boy. Let’s go find him—he’s a decent man. He’ll listen. And, we must tell him about the guy who assaulted you.”

Emilee clambered to her feet. “I’ll apologize to him, but not tonight.” Her lower lip trembled; her eyes brimmed. “I’m not ready to tell Douglas about the groper. He’ll then lose all his respect for me.”

It was late afternoon on December the eleventh, and the peace between Mr. Harding and Miss Stephens still had to be made. The latter found a reason (or fabricated one, according to her roommate) on a daily basis for three consecutive days not to visit the printing shop. In her defense though, it was noticed that since they’d left port in Table Bay, at least once a day, sometimes even twice, Miss Emilee was seen hanging over the railing retching (or over the sides of the hand basin in their cabin), her complexion mint-tinged, struggling to find harmony between her empty innards and the incessant rolling, heaving, and dipping of the Windsor Castle, stabilizers in spite.

Emilee refused to say a word further about the man who had assaulted her on deck. She refused that they report the incident to the Captain or port authorities.

Caroline felt compassion for her friend. When they had crossed the imaginary line in the ocean that morning, leaving the South and entering the North, the realization dawned on them of the infinite distance that had been put between them and their families. The sea journey was all excitement on the surface, but at night in their berths, when neither of them could sleep, they would listen to the hum of the engines, taking them farther away from where it was safe and familiar, and closer to the vast unknown.

That Thursday afternoon, Caroline cornered her friend in the coral lounge. There would be no further excuses or procrastination tolerated. Seasick or not, peace had to be made.

“Emilee, you broke a promise.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about. Please let me pass.”

“No, not until I receive a solemn undertaking from you.”

A light blush crept into Emilee’s face. “He’ll refuse to speak to me.”

“You didn’t commit a crime. He didn’t think what he was saying, and you got the tequila to speak on your behalf.” Caroline then leaned forward and pressed down on her friend’s shoulders, forcing her to sit.

Caroline lowered her voice. “You never told me. Did you secretly hope Douglas would take us to our cabin afterwards and have sex with us—well, at least with one of us? He definitely likes us.” She giggled and turned crimson as she leaned closer.

Emilee’s blush intensified. She mimicked their headmistress’s voice. “Miss Washington, it is unbecoming for a young lady of your class and upbringing to have such carnal thoughts.”

“You didn’t answer my question.”

“Caroline, he’s a beautiful young man, but it would have been wrong. We’re not married. You know that.”

“I don’t know anymore. Douglas is not like the other boys—it might have been different.” Caroline gave a longing sigh.

Emilee took her friend’s hands, held them tight, and kissed both. She was relieved that Caroline could not read her own confused mind, which at that moment had longings all of its own. She was longing for someone strong and lithe who would fall in love with her. She blushed again when she thought of the word Douglas had used—copulating—that had so little meaning. She needed commitment. A special person who would love her, hold her, without hurting her. She was so scared for a man to touch her again, touch her there. Her secret place was not to be taken by force—only to be given by her.

She pulled the now-standing Caroline closer and hugged her. My dear, dear friend. This someone would have to take great care—be a master of patience. But it wouldn’t be Douglas.

“You fancy him.” Emilee stated the obvious.

“It’s not true.”

“Miss Washington, you have my blessing.”

“What are you talking about? Come, enough babbling. We have to go find him and get you to make peace.”