1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Raanan Editeur

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

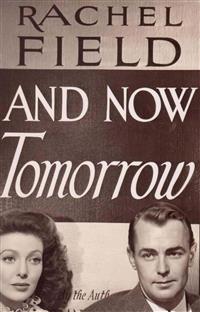

And Now Tomorrow is a novel by Rachel Field, first published in 1942. Emily Blair is rich and deaf. Doctor Vance, who grew up poor in Blairtown, is working on a serum to cure deafness which he tries on Emily. It doesn't work. Her sister is carrying on an affair with her fiance Jeff. Vance tries a new serum which causes Emily to faint... Will it work this time ?...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

SOMMMAIRE

AND NOW TOMORROW

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

RACHEL FIELD

AND NOW TOMORROW

1942

Raanan Editeur

Digital book994| Publishing 1

And, when the stream

Which overflowed the soul was passed away,

A consciousness remained that it had left,

Deposited upon the silent shore

Of memory, images and precious thoughts

That shall not die, and cannot be destroyed.

WORDSWORTH

TO

ROSALIE STEWART

WHOSE FRIENDSHIP BEGAN

"AT THE JUNCTION"

Author's Note

The place, action, and characters of this book are purely fictional. There is no Vance method of treatment to restore hearing, nor is the theory based on any actual medical findings.

AND NOW TOMORROW

CHAPTER ONE

It was years since I had set foot in the ell storeroom. But yesterday Aunt Em sent me there on an errand, and the souvenirs I came upon have disturbed me ever since, teasing my mind with memories that persist like fragments of old tunes.

There is a fascination in places that hold our past in safe keeping. We are drawn to them, often against our will. For the past is a shadow grown greater than its substance, and shadows have power to mock and betray us to the end of our days. I knew it yesterday in that hour I spent in the storeroom's dusty dullness, half dreading, half courting the pangs which each well remembered object brought.

So we sigh, perhaps, at the mute and stringless guitar with its knot of yellow ribbon bleached pale as a dandelion gone to seed. So we smile at the tarnished medal that set the heart pounding under the dress folds where it was once pinned. So we tremble or flush again at the flimsy favors and dance programs with their little dangling pencils and scribbled names.

"Now who was he?" we ask ourselves, puzzling over some illegible name. "I must have liked him very much to save him the first and the last dance."

And the old photographs in albums and boxes! It takes fortitude to meet the direct gaze of a child whose face is one's own in innocent embryo. It is hard to believe that the shy young woman with the sealskin muff is one's mother at nineteen beside a thin, merry-eyed young man whose features bear a faint resemblance to one's father. Their youth and gaiety are caught fast on this bit of cardboard all these years after that winter day when they sat for their pictures at the Junction photographer's. Here am I, a child of two between them, and here again at four with my arms about year-old Janice and the clipped French poodle Bon-Bon pressing close to my knees. That was the summer I first remember the big lawns and trees and high-ceilinged rooms of Peace-Pipe and all the curious New England relatives who peered at us. They asked questions that must be answered politely in English, not the French which Bon-Bon and I understood most easily. He and I still look bewildered in the picture, but Janice is completely at ease in her embroidered Paris dress and bonnet. Yes, there we are--Bon-Bon who has been still for years now under the thorn tree at the foot of the garden; Janice whose round baby eyes give no hint of the defiance I was to see there at our last meeting, and I, who will never again fit into those slippers with crossed straps or face a camera or the world with so steadfast a look.

Once when I was a child Father told me of a great scientist who could take a single bone in his hands and from that reconstruct the whole skeleton of the animal to which it had belonged. I wondered, standing alone in that jumble of possessions, among dangling clothes, old books, and discarded furniture, whether there might be anyone wise enough to reconstruct from these remnants the likeness of a family. Yet perhaps out of such very clutter some pattern does emerge if one has the insight to ferret out the faults and virtues, the hopes and shortcomings, the loves and loyalties of one such household. Merek Vance would have the wisdom and patience to do that if anyone could. But Merek Vance is three thousand miles away and busy with research of a very different sort. Besides, he would only smile and shrug in the way I know so well, and say that the ell storeroom and its contents are my problem.

He knows that I do not like problems, that I have sometimes lacked courage to accept the challenge of those that belong peculiarly to me. I shunned problems whether they took the form of choosing between a sleigh-ride party and a trip to Boston, or happened to be inside an arithmetic book and concerned men papering imaginary rooms or digging wells that required an exact knowledge of yards and feet and fractions. The same inner panic seized me yesterday when I opened a worn algebra and met those dread specters of my schooldays, a and b and their mysterious companion x that for me always remained an unknown quantity. Well, I know now that this unknown quantity is something to be reckoned with outside the covers of an algebra. I have learned that it can rise up out of nowhere to change the sum total of our lives.

There were plenty of old schoolbooks on the storeroom shelves, books with Janice's name and mine on thumb-marked fly leaves. In one I had written in a prim vertical hand the familiar jargon:

Emily Blair is my name, America my nation, Blairstown, Mass., my dwelling place, And heaven my destination.

September 19th, 1921

I must have been fourteen when I penned that, barely a dozen years ago. Yet "heaven" is a word I seldom write or take for granted nowadays. In this year 1933 I am not so confident of my dwelling place or my destination.

Another book that bore my name was a Latin grammar, with penciled jottings on margins and exercises on folded sheets of paper. I used to be rather good at Latin, though it never occurred to me then that truth or meaning might lie behind the phrases I labored to translate. But as I pored over the pages again they began to take on life and significance. Once, I realized, people had used this tongue to speak to one another, to write words warm with affection or heavy with despair. A phrase held me as I turned the pages: "Forsan et haec olim meminisse juvabit." My lips repeated the words. I wrestled with their meaning as one struggles to move the key in some rusty lock. At last I had it: "Perhaps it will be pleasant to remember even these things." I knew then that it was not some whim of chance that had sent me to the storeroom, that had guided my hand to that book and my eye to that particular phrase.

In the life of each of us, I told myself, there comes a time when we must pause to look back and see by what straight or twisting ways we have arrived at the place where we find ourselves. Instinct is not enough, and even hope is not enough. We must have eyes to see where we missed this turn or that, and where we struggled through dark thickets that threatened to confound us. I know that I have arrived at such a time.

Some day, it may be, I shall tie a handkerchief round my hair and take a broom and duster and set to work clearing out the storeroom. But I must take stock of myself before I am ready for that. I rebelled against returning to this house and the querulous wants of a tired old woman and a middle-aged man with time heavy on their hands. But I am rebellious no longer. Old times, old feelings, old hurts, old loves, and old losses must be sorted and weighed and put in order as well as outworn mementoes. We cannot simply close the door upon them and forget what lies behind it. We cannot let bitterness gather there like a layer of dust.

I fumble awkwardly for words as I sit here at this desk where I have so often dashed off schoolgirl essays full of glib phrases; where I have penned letters marred with self-pity and despair. I am done with all that now. Once I considered myself a very important person in my own world. Now I know that I matter less perhaps in the scheme of things than the tireless, pollen-dusted bee; than the mole, delving in darkness; than the inchworm that measures its infinitesimal length on a grass-blade.

I don't pretend to know what I believe beyond this--that nothing which lives and breathes and has its appointed course under the sun can be altogether insignificant. Some trace remains of what we have been, of what we tried to be, even as the star-shaped petals of the apple blossom lie hidden at its core; even as the seed a bird scatters in flight may grow into the tree which shall later shelter other birds. And so, those whose names I write here--Aunt Em, Uncle Wallace, Janice, Harry, Old Jo and young Jo Kelly, Maggie, Dr. Weeks, Merek Vance, and I--all of us are changed in some measure, each because of the others. Our flesh and blood, our nerves and veins and senses have responded under this old roof to forces and currents that we shall never be able to explain. We are scattered now, and what we did and what we said will be forgotten soon. It will fade into the unreality of old photographs, like those I stared at yesterday in the storeroom.

I shall begin with the river because without it there would have been no busy Blairstown, with its bridges above and below the falls; there would have been no mills and no bleacheries, no pulsing machinery, no smoking chimneys gaunt against the winter sky or thrusting their darkened tops through summer's dominant green. There would be no reason for trains between Boston and Portland to stop at the brick station with its black-lettered sign above the familiar trademark of the Indian War Bonnet and Pipe and the words that encircle them: "Peace-Pipe Industries."

No one thought it an ironical name until lately. Four generations of American households have known the pipe and feathers and the legend they carry on sheets and pillowcases and towels the country over: "Peace-Pipe for Quality." It was Great-grandfather Blair who made famous those four words and the product of his mill. But it was a hundred years before his time that the first Blair had made his peace with the Wawickett Indians. Their name alone has survived them in the bright, rushing waters of the river where they fished and paddled their canoes.

More than anything else in Blairstown; more even than this big stone house that rose on the foundations of the first unpretentious family farm, the river is bound up with my childhood. I cannot remember my first sight of it, for I was less than two when Father and Mother brought me back from France to be displayed to my New England relatives. Father used to swear that even then the river had a queer power over me. He would stand on the bridges and lift me up in his arms, and I would stare, spellbound, at the torrent of shining water that fell endlessly, and at the fierce steaming, churning whiteness of the rapids below. In other summers when we returned and Janice was the baby to be held aloft, I would stand peering through gaps in the stonework, never tiring of the liquid drama that went on without beginning or end.

Father was amused and tolerant of my passion for the river, and Aunt Em openly gloated over my preference, but Mother did not seem altogether pleased. She died before I was seven, and so she must always remain for me a dim figure in rustling skirts, with a voice that kept unpredictable accents and cadences because she had learned to speak first in Polish. If we children happened to be with her when we crossed the bridges, she always hurried us over, ignoring my pleas for "just one more little look." Only once I remember prevailing upon her to pause there, and I have never forgotten the occasion. She stayed so quiet at my side that her silence at last made me curious. Though I was young to notice such things, I was struck by the expression of her face as I peered up into it. She was not looking either at me or at the seething water. Instead she stayed still as stone staring over at the mills and the chimneys and the small brick and wood houses where the mill hands and their families lived. Her eyes had grown dark in the soft, pale oval of her face. They held a remoteness that chilled me.

"Mama!" I tugged at her hand. "Don't look over there at the ugly side."

My words brought her eyes back to me, and she answered in her slow, rich voice that blurred softly where words met.

"So you feel shame for that already, my little Emily! But don't worry. You are safe on your side of the river. You're all Blair."

I was to hear that last remark many times afterward. But as often as it has been said, I can never hear it without thinking of that day on the bridge when my early complacency met its first shock. There we stood together, hand in hand, yet we had hurt each other. The river, shining in the summer sun, and the smoky bulk of the mills with those small crowded houses and yards full of washing, were somehow all part of what had come between us.

Often and often I think of it, until sometimes the Wawickett River becomes more than a hurrying stream that has furnished the power for Peace-Pipe Industries and brought prosperity to our family. It has become a symbol to me, as it must have been to my mother that day. For in spite of its bridges the river did then and does now mark the boundary between secure and precarious living; between the humble and the proud. Some may cross from one side to the other as my mother did; as young Jo Kelly was to do years after. And there are a few, like me, who stand on the span of its bridges, knowing that we belong to both--troubled and uncertain because we cannot renounce all of one side for all of the other.

CHAPTER TWO

"Always do what's expected of you, Emily," Father used to say, watching me with eyes narrowed in a habit acquired by years of painting. "I never learned the trick, but it saves a lot of trouble in the end."

No, Father never did what was expected of him, but perhaps it wasn't altogether his fault. Everyone expected almost too much of Father, and he was born wanting to please everyone he met. He made people happy too easily; and by the same token he disappointed them, because no one can please everybody all the time. He was the oldest of those three Blairs, the handsome, clever one of the family. Aunt Em came next to him--tall, and serious and distinguished-looking even before she was full-grown. She had inherited the Blair shrewdness for business, along with the Blair stubborn streak and the Blair energy. It's a pity that her passion for activity couldn't have been directed as successfully as the Wawickett River's forces had been harnessed into power for the mills. Uncle Wallace came last in order of age and importance, a position he has maintained ever since.

Always he has been referred to as "the other Blair brother." He has never seemed to resent this. I think it's all he ever wanted to be. A pleasant, uncommunicative man, contented with the mill routine, occasional business trips, his golf, and his collections of stamps, Uncle Wallace has fitted himself into the scheme of life to which he was born better than any of us. He hasn't Aunt Em's will to fight against the current. He asked little of life and has paid the penalty of those who ask that; for even that little has been taken away from him.

But with Father it was different always. His good looks and gifts marked him from boyhood. Yet he managed, miraculously, not to be spoiled, and he was never taken in by himself. Therein lay his salvation. It was also the reason why he never became a first-rate artist. Tolerant of others' work, he was ruthless when it came to judging his own. And so his vigor and friendship poured out in all directions, enriching those whose genius bore the fruit he was often the first to recognize. In the memoirs of his contemporaries, painters, writers, and musicians living in those more leisurely years of the early 1900's, Father's name slips in and out like some comforting and casual tune. I like to come upon it and know that he mattered more than the canvases that bear his name in the corner and that will never bring a price worth mentioning.

"Want to come in the studio and play being a model?"

Those were words I loved to hear, and I always sprang to answer the invitation. Father had a flair for catching likeness. The best things he painted are portraits of Mother and of us as children. I never tired of sitting for him in the high, littered studios he made so completely his own, whether he inhabited them for a year or a month. I can see his big left thumb hooked into the hole of the palette where he had squeezed brilliant daubs of vermilion and cobalt and burnt sienna. His right hand held the long brushes with a strength and delicacy I shall never forget. He seldom talked when he painted, but he used to hum in deep, contented monotony like bees in an apple orchard in May. That pleasant rumble is bound up in my mind with Father and his studio. It will always be part of the smell of turpentine and linseed oil and the tobacco in the pipe he smoked; part of the image of a tall man with eyes as blue as his paint-spattered smock.

Janice can barely recall the studio days, though she says she remembers the afternoon receptions and evening gatherings when we would be carried from bed in our nightgowns to be displayed to the guests. I was never the success that Janice used to be on these occasions, though I was much more dependable when plates of refreshments were entrusted to our passing. Janice needed no encouragement to dance in her white nightgown and red slippers. She was always applauded; and no wonder, for she was a captivating sprite with her fair hair tumbled on her shoulders and falling into her eyes that shone as dark and bright as blackberries. She was the despair of those who tried to catch her on canvas, for she was changeable as quicksilver. I was considered quaint and paintable with my solemn blue eyes and brown straight bangs.

"That one," people would remark, "is her grandfather Blair all over again. Too bad she couldn't have been a boy to carry on the family name as well as the family features."

Once again Father had failed in what was expected of him. Having married a Polish girl worker in the mills and having abandoned the family business, at least he might have provided a son instead of two daughters. But he didn't seem to mind, and from the day I was brought back to wear the Blair christening robe and be called by her name, Aunt Em accepted the marriage and Mother.

"You couldn't wonder he fell for her," Maggie told me once when I questioned her about that match which had been the talk of the county. "When a Polack girl's beautiful she puts the come-hither on a man once and for all."

"The come-hither, Maggie?" I persisted, for I was still very young and curious. "What's that?"

"You'll know right enough some day."

That was all I could ever get out of Maggie on the subject, but I know now how it must have been that day when my father saw my mother sliding down a long patch of ice by the mill gates. The story has taken on the quality of a legend all these years afterward. It was closing time, and the workers were thronging out in the November dusk, chattering and jostling one another as I have seen them so often at that hour, a human torrent of youth and animal high spirits. Skirts were longer in those days, and there were shawls and braids and thick coils of hair instead of berets and bright scarfs over permanently waved, bobbed heads. But the effect must have been much the same then as now. Father had been out of college for several years, and the mill routine had been growing more and more irksome. His heart wasn't in the business. Besides, he was already set on his painting. In the mill workers he saw living models that he longed to put on canvas. I don't mean that he was indifferent to some Polish or Lithuanian girl's good looks, any more than the other men in the office. But he had an artist's eye for line and color as well as masculine appreciation of a curved body, full lips, or trim ankles.

It was fate, or destiny, or just plain good luck that singled Mother out from the rest that winter day. The closing whistle had blown, and Father stood by a window watching the girls hurrying through the mill yard. Ice had formed round one of the exhaust pipes. There was a smooth frozen stretch below it. Suddenly a girl broke away from the rest and took it in one long, graceful slide. It was the most simple, spontaneous response that he had ever seen, he said afterward. Though he couldn't see her face for the gathering twilight, he couldn't forget the free sure motion of her body, with arms held out to keep the balance true, or the way her warm breath streamed out in the dullness under a red knitted shawl that wrapped her head like the crest on a woodpecker.

That was how it began--strange and improbable enough to be the climax of some old-fashioned romance in paper covers. Father must have been born a romantic, but he must have had his share of the Blair persistence to carry the courtship through. Certainly Mother gave him very small encouragement. She had scruples against accepting attentions from the mill owner's obviously admiring son. Lots of girls had set their caps for Father, and he was well aware of that. It made him cautious at picnics and dances and house parties. Perhaps it made him all the more vulnerable to this girl with her foreign name and speech and her self-guarded beauty. Even more than the heavy coils of light brown hair, the soft oval face and wide-set dark eyes, it was this quality of personal dignity in her that must have stirred and held him.

Well, in love there's no choosing, and Father and Mother were ready for love and each other. I shall never know when they first answered the summons; when they first guessed what had taken possession of their separate lives, drawing them so surely and inexorably together. I shall never be able to conjure up what passed between them during the months when each struggled to keep an impossible freedom. But I can picture how it may have been as they met, day after day, while the building vibrated about them and the mill machinery throbbed like a gigantic pulse. It must have seemed almost a magnified echo of their own pulses and the beating of their two quickened hearts. Yes, that is how I like to think it may have been--shuttles weaving, bobbins twisting, threads like millions of humming harp strings, fine-spun about them. And so they became part of the pattern of life, which may not vary its design, though the two who give themselves to its making are always new.

Afterward, when Aunt Em had accepted the marriage, she made rather a point of stressing Mother's background. Polish, yes, but far from the ordinary run of mill girls. Helena Jeretska came of good stock. Her father had been a music teacher, and her mother had had a fair education. Both had died in a typhoid epidemic shortly after landing in Boston, and another immigrant family of quite a different type had taken the child and brought her up with their own. Somehow they had drifted to Blairstown and the mills. Mother had gone to work there at seventeen.

"Oh, yes," I can almost hear Aunt Em saying, "she's quite pretty, almost beautiful in a different sort of way. I think Elliott expects to spend his life painting her. Well, naturally, it's hard to have him go so far away, but Paris is the place for artists. It's not as if the business had ever been congenial to him, and Wallace and I can do our part. Peace-Pipe Mills have always been family-run, and I trust they always will be."

It never took Aunt Em long to recover from any shock. I wasn't born till two years after she met that one, but I've seen her take a good many since. I know the set of her head and lips and the old rallying phrases she summons for times of need. Only lately have I known her to admit defeat, and she has never accepted it. Even now with her once active body stiff and restricted of motion, I can tell that she believes in the power of her own will to accomplish the inevitable. I am reminded of a picture in an old history book--King Canute sitting in state with salt waves breaking about his feet, commanding the tide to turn back.

Aunt Em will resist the encroaching tides of change right up to her last breath, and I love her for it. For all the difference in our ages she is younger than I in some respects. She has not learned what I am only just now beginning to understand--that no matter how hard and faithfully we may try we can never compensate another for some lack in his or her life.

In my own case this sense of obligation came about naturally through the circumstances that followed Mother's tragic death the summer I was seven. She had been fatally injured in a motor accident that spring in Paris, and Father moved in a daze of despair during those days when doctors and nurses fought hopelessly to keep her alive. Father was like a stranger to Janice and me for a long time. His new black coat didn't smell comfortingly of paint and tobacco, and we were glad when men came to crate the canvases and pack furniture and when our things were put in trunks and sent to the ship that would take us back to America. We missed Mama, but our minds were full of the thought of Peace-Pipe. We longed to see how our big brown poodle, Bon-Bon, looked after a winter without us. We wanted to be back before the lilacs were past blooming and in plenty of time to pick wild strawberries in the meadows on the outskirts of town. Father seemed to care little for important things like that, though he was very indulgent of us on the crossing.

One occasion on the voyage I recall with peculiar distinctness. It was the night of the captain's dinner, and Father had promised that I might sit up later than my usual bedtime to watch the people in evening dress go down to the dining saloon. I was ready long before the dinner hour, and to quiet my impatience Father took me on deck. We sat very close together watching the last fiery shreds of cloud dim as the steamer throbbed on tirelessly through darkening water. It was exciting as if Father and I had escaped to some far and secret place. The tones of his deep voice when he spoke to me out of the dimness were all part of that night, giving emphasis to his words.

He had been speaking of Peace-Pipe and Aunt Em when suddenly his tone changed.

"This summer won't be like the others," he said. "You and Janice are going to be Aunt Em's little girls from now on."

I must have trembled or crept closer, for he added quickly:

"Of course you'll always belong most to me, but you mustn't ever let Aunt Em think that. She needs you, and you'll try hard to make her happy, won't you?"

So I promised, filled with a pleasant glow of responsibility. Yet it seemed a queer thing to me then, as it does to me now, that anyone should have to try hard for happiness.

CHAPTER THREE

There is one day I recollect most clearly from that summer of our return, because it was my seventh birthday and because it was my first meeting with Harry Collins.

From its start the early August day was mine. I ran out barefoot into a world of dew and opening flowers; of robins making little watery calls and splashing at the rim of the lily pool. I measured my seven-year-old height against the vigorous green of hollyhocks by the fence; but, stretch as I might, I could not reach the lowest pink rosette. By the side door a huge old snowball bush bent double under its load of green and white. I crept beneath and felt the cool shock of dew upon me from shaken branches. Myriads of bees were filling it with sound. As I crouched there in the morning stillness they seemed louder and more insistent than I have ever heard them since. That tireless sound made me think of the water going over the Falls; like the throbbing mill machinery when it came distantly from across the river.

Butterflies and birds were everywhere as well as bees. Droning or darting or drifting, they passed me on invisible currents of air. I was aware of them wherever I moved. There was an intensity to their busyness that made me a little in awe of them. They went about their work as if the world were coming to an end at sunset. I think something of the fierce urgency of their frail bodies must have been imparted to my young self that day to make me remember the shape and color and sound of each moment as I do these years afterward.

The trumpet vine that covered the side porch is gone now, but I can still see the miraculous spinning of a hummingbird above it. I knew that its wings were a rainbow whirl because they revolved so fast, yet they gave an illusion of stillness, and the long bill seemed held fast to the magnet of a trumpet flower. I stood there, elated and alone, with my bare feet rooted to wet earth. Some vigorous, sweet essence of summer and sun flowed through me in that moment of breathless watching.

"Happy birthday, Em'ly," Janice called down from an upper window, and the spell was shattered.

Then breakfast, with waffles and honey and packages to open, claimed me. Father had gone to Boston, but he had promised to be back on an afternoon train in time for my party. I knew there would be more presents in his arms, and meantime there were plenty to keep me busy--a new doll and carriage and a boat with sails that could really put to sea in the waters of the lily pool. I much preferred it to the blue enamel locket that had belonged to Aunt Em when she was a little girl, but, remembering my promise to Father, I tried to let her think that was my favorite present.

Uncle Wallace let us walk to the bridge with him, and when we returned Old Jo Kelly and young Jo, his grandson, were waiting to wish me happy birthday. They lived in quarters over the stable. Old Jo had been gardener on the place as long as Father could remember. He had a bouquet of flowers for me, and young Jo had brought three alley marbles and a tin soldier.

"You can play he's captain," he suggested when he saw the new boat. "He don't stand very good alone, but you can lash him to the mast."

We wanted young Jo to play with the new boat, but he went off to help his grandfather haul fertilizer. They worked side by side, those two, the best of cronies for all the sixty-odd years' difference between them. Young Jo's parents had died when he was a baby, and he had always lived with his grandfather.

Even then there was something to be reckoned with about young Jo Kelly. Gay and good-natured though he was for the most part, he could summon up furies that were terrifying to behold. I have seen his blue eyes darken and his lips turn white when he pleaded with his grandfather not to set traps for the moles that were ruining our lawns. His hands were clever at unfastening traps. If rabbits or squirrels or mice could have given testimonials, then young Jo Kelly's name would surely have been blessed. Aunt Em, I remember, once had a long conversation with him on the subject of ridding the place of English sparrows. He listened quietly through her explanation that they were noisy, dirty pests who drove the songbirds away. But her arguments left him unconvinced.

"Sparrows are just as human as any other kind of bird," he told her firmly, and for once Aunt Em had no answer.

My party began on the stroke of four when the Parker twins, Nancy and Joan, appeared, bringing their cousin who had arrived that morning. His name was Harry Collins, and he was older than the rest of us by several years. I can see him now as he looked coming up our drive in his white sailor suit with a twin on either side in pink and blue dresses. The sun made his sandy hair look redder than it really was, and he walked easily with an air of being on very good terms with the world. The twins carried gifts, conspicuously displayed, but he came empty-handed.

"Hello," he called when they were within hailing distance, and I saw that his eyes were hazel with gold flecks that matched the freckles on his nose. "How old are you?" he demanded pleasantly.

"Seven today," I explained.

"Seven's nice," he encouraged me. "Wait till you get to be ten."

"Are you ten?" I ventured.

"Well, practically," he amended.

"Not till after Christmas," the twins chorused. "You only have a right to say you're going-on ten."

"'Practically' means the same thing," he insisted, and once more he smiled at me.

When Harry Collins smiled one seldom questioned his statements. He turned a not very expert handspring on the grass while we four little girls watched admiringly. If he made a mistake he somehow convinced you that it had been intentional, merely a delightful variation from the usual pattern.

We were joined just then by Jim and Lolly Wood from across the Square, and by the time I had opened their presents young Jo Kelly had appeared from the back garden, more scrubbed and combed than I had ever seen him.

"Who's the kid?" Harry Collins eyed Jo critically.

I felt uncertain just how to explain him. Young Jo Kelly, we had always taken for granted without classification. Yet I knew that he did not usually rate parties.

"Oh, he lives down there," I answered evasively, pointing vaguely in the direction of the garden.

I was glad that Maggie and Aunt Em appeared just then to supervise a hunt for presents hidden in the shrubbery. After that we played hide-and-seek, and it was then that I found the injured chipmunk under the big hemlock.

Bon-Bon, our French poodle, really made the discovery. I heard his excited barks, and by the time I reached him the tawny ball of fur with dark and light stripes was electric with fright. My first impulse was to pick it up, but Bon-Bon's behavior made me hesitate. I seized him by the collar instead, and it took all my strength to hold him back. The others ran up, attracted by the barkings and my cries. Harry Collins reached us first and bent over the chipmunk, which had begun to make terrified chitterings and to bare sharp little teeth.

"Gee, look at it spit!" he cried. "Get him in a box quick, and then we'll have a pet squirrel."

But Harry had reckoned without young Jo Kelly.

"You leave that chipmunk be," he ordered. "Can't you see it's hurt?"

"Then it'll be all the better in a box. We can crack nuts for it, and--"

Young Jo pulled him away.

"Don't you touch him," he said. "They always die if you shut 'em up."

"He'll die if the dog gets him."

"Sure." Jo was growing exasperated. "We've got to get him back up there."

He pointed to the hemlock, but just then Bon-Bon made another lunge, and I all but lost my grip on his collar. When I looked up again I saw a brown fist double and strike out. It thudded against Harry Collins' face, and though he was so much bigger than young Jo, the sudden surprise of the blow made him stagger back. The next moment Jo stooped down, stuffed the chipmunk into the front of his shirt and made for the lower branches of the hemlock. Up and up he went, hand over hand, while we all watched from below and I still clung to Bon-Bon.

"He hit Harry," the twins kept saying. "He hit him right in the face, at a party too."

"Jo Kelly's got no business coming to parties, anyhow," I heard Lolly Wood protesting. "His grandfather's just your gardener, isn't he?"

The dog's barking gave me an excuse not to answer, and Aunt Em was calling as she hurried to us across the lawn: "Children, children, what on earth is all the racket about? Leave that dog, Emily, and come here."

But I hung on. I wasn't going to let Bon-Bon leap against the tree while young Jo was balanced precariously up there among the spiked boughs. He had climbed to a place where he could brace his feet between two branches and while he held on with one hand I saw him fumbling in his shirt with the other. I saw him take something out and reach up and up with the branch he clung to sagging under his hold. Suddenly he gave a sharp cry and then he was slipping and clutching frantically to keep his hold. Before any of us could move or cry out he came crashing through a shower of twigs and green needles to lie in a heap at our feet.

Everyone began to cry and run after that. I let Bon-Bon go free and dashed off to hunt for Old Jo Kelly. By the time I had found him and we reached the hemlock tree again Maggie had taken charge with wet cloths and spirits of ammonia.

My birthday party ended with less festivity than it had begun. We were hustled off to the arbor to eat our ice cream and cake with strict orders to keep out of the house and not to ask questions.

"Send them home as soon as you can, Maggie," we heard Aunt Em say. "Mr. Elliott's just back and I've sent him after Dr. Wells."

We gulped great spoonfuls of ice cream and talked in excited whispers. Later we stood at the gate in a subdued little group.

"Goodbye," the twins said politely. "It was a nice party, and we had a lovely time."

"You asked us from four to six, and it's only a quarter to," Lolly Wood said reproachfully as they turned to go.

"So long, kid," Harry Collins laughed through the fence at me. "I'll be seeing you."

"My birthday'll be next," Janice was saying beside me. "You won't have another for a whole year."

"Mine's not over yet," I reminded her.

But I felt low-spirited because the party had been spoiled before it was over and because young Jo had been hurt. The sun had slipped to the level of the lawns, lighting them to a strange clear green, deeper than the emerald in Aunt Em's ring. The frogs had begun to grunt in their deep guttural under the lily pads in the pool, and birds made sleepy-sounding calls that filled me with a sadness I could not explain or share. Morning with its shimmering promise seemed years ago. I did not care when Janice pounced on a forgotten package and claimed it for her own.

Upstairs in the room where they had carried young Jo I could hear the murmur of voices and sometimes a long, whimpering cry. Then it grew suddenly quieter and a queer, sweetish smell drifted down to us.

"Emily! Janice! Where are you?" Aunt Em was calling us as she followed Dr. Weeks out to his car. We ran to her with questions, and she comforted us.

"Young Jo's going to be all right," she explained. "The doctor has just been setting his leg where he broke it. No, it didn't hurt Jo much--he had a whiff of chloroform, and he slept till the splints were on. We'll keep him in the spare room till he's able to be up and about."

We were allowed to say good night to young Jo later, conversing through the door. He looked no bigger than a chipmunk himself in the middle of the big carved walnut bed. His voice came faintly from between the pillows.

"He bit me," young Jo explained. "I reached to put him in that hole and he up and bit my thumb."

"That was mean," I said, "when you were only trying to save him."

"Oh, he didn't mean no harm." Jo would never let a word be spoken against anything in fur or feathers. "Chipmunks just get rattled."

Maggie was unusually short when she put Janice and me to bed that night. Her temper had been tried by the afternoon, between the extra work of the party and caring for an unexpected invalid. She seemed inclined to blame me for being the cause of the catastrophe, and she made few responses to our chatter, hurrying us through baths and prayers.

"Now, then, no more mischief," she warned us sternly. "There's been plenty for one day."

"What's mischief, Maggie?" Janice demanded from her bed.

She looked so pretty with her yellow hair shaken round her ruffled gown and her eyes dark and shining in her flushed face that Maggie couldn't stay altogether grim.

"Now, Miss Janice," she remonstrated, "you know what I mean, so you needn't put on the innocent airs. You just remember the mother of mischief's no bigger than a midge's wing."

Janice fell asleep before darkness filled the room. But I watched it creep over the familiar pieces of furniture. I hid my head under the covers when it took my clothes draped over a chair and turned them into terrifying shapes. Outside, the frogs sounded very loud and insistent. Suddenly I wanted Father to come and tell me that everything was all right. I remembered in that moment that Father had not appeared at my party according to his promise. In the excitement I had forgotten that. Surely he must be back by now. I began to feel very sorry for myself lying awake up there in the darkness. I slipped from bed and felt my way across the room. The doorknob eluded me. I fumbled for it in panic, and tears overwhelmed me before my hands felt the reassuring cold brass.

Downstairs lights were bright, and I could hear voices coming from the back parlor. My bare feet made no noise; and although I was breathing hard I managed to smother my sobs. When I reached the portieres I paused, fearing that there might be visitors. I knew Aunt Em would be mortified to have me burst in on guests, so I listened though I knew that that, too, was strictly against rules.

"But what if there is a war over there?" Uncle Wallace was saying. "That's no reason for you to get mixed up in it."

"Thank your lucky stars you're here with the children, not caught over in the midst of it," Aunt Em's voice broke in.

"Besides"--it was Uncle Wallace speaking again--"they all say it can't possibly last more than three or four weeks."

I heard Father give an impatient grunt before he spoke.

"Believe what you want to," he answered. "I happen to know what France and now England too have got ahead. Everyone talked war last year, but no one thought it would come so soon. It's happened, and I know where I belong."

"But, Elliott"--Aunt Em's voice sounded as if she were trying hard not to cry--"you can't really mean what you're saying. There's nothing to take you there and everything to keep you here: your work, your children, and--"

"And Peace-Pipe!" Father gave a short laugh that had no fun in it. "No, Em, the mills will go on, the way they always have. And the children will grow the way children always do, whether I'm here or not. As for my work which you so kindly mention, you know as well as I do that I'm no great shakes of a painter, and ever since I lost Helena--"