8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

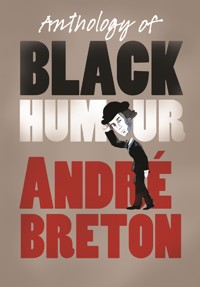

- Herausgeber: Telegram Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

This is Breton's definitive statement on l'humour noir, one of the seminal concepts of Surrealism. In his provocative anthology of the writers he most admires, Breton discusses the acerbic aphorisms of Swift, Lichtenberg and Duchamp, the theatrical slapstick of Christian Dietrich Grabbe, the wry missives of Rimbaud, the manic paranoia of Dali, the ferocious iconoclasm of Alfred Jarry and Arthur Cravan and the offhand hilarity of Apollinaire. For each of the authors included, Breton provides an enlightening preface, situating both the writer and the work in the context of black humour - a partly macabre, partly ironic, and often absurd turn of spirit that Breton defined as `a superior revolt of the mind'.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

ANTHOLOGY OF BLACK HUMOUR

André Breton

Anthology of Black Humour

Translated from the French and with an Introduction by Mark Polizzotti

TELEGRAM

First English edition published by City Lights Books, San Francisco, 1997

This edition published in 2009 by Telegram

ISBN: 978-1-84659-074-0 eISBN 978-1-84659-198-3

Copyright © Société Nouvelle des Editions Pauvert 1979, 2009 Translation and Introduction copyright © Mark Polizzotti 1997, 2009 Acknowledgments for the use of copyrighted material appear on 413

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Manufactured in Lebanon

TELEGRAM

www.telegrambooks.com

Contents

Introduction: Laughter in the Dark, Mark Polizotti

Foreword to the 1966 French Edition

Lightning Rod, André Breton

Jonathan Swift

D.A.F. de Sade

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg

Charles Fourier

Thomas De Quincey

Pierre-François Lacenaire

Christian Dietrich Grabbe

Pétrus Borel

Edgar Allan Poe

Xavier Forneret

Charles Baudelaire

Lewis Carroll

Villiers de l’Isle-Adam

Charles Cros

Friedrich Nietzsche

Isidore Ducasse (Comte de Lautréamont)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

Tristan Corbière

Germain Nouveau

Arthur Rimbaud

Alphonse Allais

Jean-Pierre Brisset

O. Henry

André Gide

John Millington Synge

Alfred Jarry

Raymond Roussel

Francis Picabia

Guillaume Apollinaire

Pablo Picasso

Arthur Cravan

Franz Kafka

Jakob van Hoddis

Marcel Duchamp

Hans Arp

Alberto Savinio

Jacques Vaché

Benjamin Péret

Jacques Rigaut

Jacques Prévert

Salvador Dalí

Jean Ferry

Leonora Carrington

Gisèle Prassinos

Jean-Pierre Duprey

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Laughter in the Dark

Breton’s Anthology of Black Humour is aptly named in more ways than one. Originally intended as both a showcase for the Surrealist conception of humour and a way for its impecunious author to earn a quick advance, the book ultimately took Breton longer to assemble than practically any other work. It suffered years of publisher’s delays, ran afoul of the censorship board and contributed to its author’s dangerously poor standing under the Vichy government, and in the final account earned Breton very little money at all. As to its philosophical impact, and despite Breton’s lifelong view of it as one of his major statements, the Anthology has never received the kind of attention granted most of his other books, making do instead, in the general response to Breton’s opus, with the condescending status of poor cousin.

This relegation to the second tier is unjustified, for the Anthology of Black Humour not only gathers into one volume texts by many of Surrealism’s most important precursors and practitioners, but it still stands as the first and most coherent illustration of a form of humour that, as Breton notes in his introduction, has only gained in prominence since the concept was first codified. Who today – in the wake not only of the Theatre of the Absurd, but even more so of the writings of Kurt Vonnegut, John Barth, et al., not to mention Monty Python’s Flying Circus and its avatars, the films of David Lynch and the Coen brothers, or even such mainstream television fare as Saturday Night Live – could fail to recognize a distinct timeliness in the dark, acidic humour of Sade’s jovial Russian cannibal or Leonora Carrington’s party-going hyena, or with the dismissive whatever echoing from the selections by Rimbaud, Apollinaire, and Jacques Vaché?

There is, in fact, a lot of what today we would call ‘attitude’ in these pages. This attitude, which takes the form of both a lampooning of social conventions and a profound disrespect for the nobility of literature, is perhaps the one thread that links these otherwise disparate writers: from Jonathan Swift’s famous, deadpan prescriptions for overpopulation to Jacques Rigaut’s nonchalant relations of his suicide attempts, from Charles Fourier’s delirious cosmogony to the mind-bending wordplay of Jean-Pierre Brisset and Marcel Duchamp, from Alphonse Allais’s neighbourly pranks and Alberto Savinio’s rude soirée to Alfred Jarry’s pataphysics and Charles Cros’s physics of love. If some of Breton’s choices (particularly those that most explicitly challenge the rules of ‘acceptable’ society) occasionally appear a bit heavy-handed, they nonetheless join with the others in subverting our expectations, upending our preconceived notions of life and art, and often – no small feat – making us laugh.

This laughter, however, is always a little green around the edges, for as Breton is quick to point out, black humour is the opposite of joviality, wit, or sarcasm. Rather, it is a partly macabre, partly ironic, often absurd turn of spirit that constitutes the ‘mortal enemy of sentimentality,’ and beyond that a ‘superior revolt of the mind.’ Taking his cue from Freud’s remarks in Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious – the Freudian terminology recurs throughout his presentations – he describes this form of humour as ‘the revenge of the pleasure principle (attached to the superego) over the reality principle (attached to the ego) … The hostility of the hypermoral superego toward the ego is thus transferred to the utterly amoral id and gives its destructive tendencies free rein.’ A recipe for psychic unrest, perhaps, but hardly the stuff of mirth.

Still, despite the very modern aspect of black humour, the concept itself dates back well before Breton’s definition of it, to Jonathan Swift at the beginning of the eighteenth century (Swift who was already listed in the 1924 Manifesto as being ‘Surrealist in malice,’ and whom Breton here singles out as humour’s ‘true initiator’). Breton himself had begun appreciating this kind of humour in 1914, via some recently unveiled works by Rimbaud: as he saw it, Rimbaud’s offhand rejection of French nationalism during the Franco-Prussian War perfectly mirrored his own scepticism at the outbreak of World War I, and, perhaps more to the point, sounded the bitter guffaw over which the bellicose folly of his times had little hold.

But his first direct contact with the living spirit of black humour did not come until a year and a half later, during his service in the army medical corps, when he met a fellow soldier named Jacques Vaché. Although the two young men knew each other for a comparatively short time, and although Vaché’s written output consisted of little more than a series of ‘letters from the front,’ his importance for Breton can be gauged not only by his prominent inclusion in the Anthology, but also by the various essays Breton would write about their friendship over the following years (notably in The Lost Steps). It was Vaché who provided Breton with his first definition of humour as it applies here – ‘a sense … of the theatrical (and joyless) pointlessness of everything’ – and whose words and actions showed the young intern just how unsettling its manifestations could be. ‘In Vaché’s person, in utmost secrecy, a principle of total insubordination was undermining the world,’ Breton later commented, ‘reducing everything that then seemed all-important to a petty scale, desecrating everything in its path.’ From that moment on, this particular form of humour – or umour, as Vaché spelled it – would become a main preoccupation of Breton’s, and a major criterion in his evaluation of works and individuals.

Nevertheless, it was not actually Breton who came up with the idea of an anthology of black humour. In early 1935, finding to his distress that his recently married second wife, Jacqueline Lamba (the heroine of Mad Love), was expecting their first – and Breton’s only – child, and desperately short of money, he appealed to his friend Léon Pierre-Quint, the editorial director of Editions du Sagittaire, to find him a book project that would demand little time and effort, but whose commercial prospects would justify a reasonably high advance. After several false starts, Pierre-Quint and the American poet and translator Edouard Roditi, a member of Sagittaire’s editorial board, proposed an international anthology of writings that would gather and introduce the main proponents of umour.

By the end of 1936, Breton had assembled texts by the forty original contributors to the Anthology (the last four, plus Charles Fourier, were added in a later edition, while several extracts by the original authors were deleted). He had also drafted the short introductory pieces that preface each excerpt, as well as ‘Lightning Rod,’ his overall foreword to the volume, in which he elaborates his own theory of black humour.

Unfortunately, by this time as well, Editions du Sagittaire was on the verge of bankruptcy, and after some hesitation Pierre-Quint ceded the rights to rival publisher Robert Denoël. But neither was this edition to see the light of day: Denoël was experiencing his own financial difficulties, on top of which Breton’s requirements for the book – photographs of the contributors throughout, a full-colour cover designed by Duchamp, a Picasso etching for the deluxe editions – made the production costs prohibitive. In 1939, after France once again found itself at war, Denoël abandoned the project altogether.

In despair, Breton then turned to Jean Paulhan of Editions Gallimard, the publisher of several of his best-known works (among them Nadja and Mad Love), hoping that Paulhan could rescue the Anthology from oblivion. His letters over the following months revealed an anxiety that – while largely due to worry over the Fascist menace, the constraints of military service, and his enforced separation from Jacqueline, their four-year-old daughter, Aube, and the majority of his friends – seemed to take as its main focus the fate of his anthology. ‘I would ask you and Gaston Gallimard to please not make me lose hope over Black Humour,’ he wrote to Paulhan in January 1940. ‘You know that the silence surrounding me is at least partly due to the non-distribution of my books.’ And two months later, he pleaded directly with Gallimard to publish the anthology ‘in the very period we are living through, [for] I believe that afterward it would no longer be quite so situated.’

Breton’s concern was not merely that of an author eager to see his work in print. In his view, the message implicit in the Anthology was even more pertinent to the wartime climate than it had been several years earlier. ‘It seems to me this book would have a considerable tonic value,’ he told Paulhan at the time. Just as Rimbaud’s anti-war poems and letters had stayed him in 1914, so now he wanted to further that message, to spread the word to youths of the next generation who refused the jingoism of the war effort, as he himself had refused it twenty-five years earlier. In this regard, it is no accident that five of the Anthology’s forty original contributors are Germanic: a devotee of Hegel, Marx, Freud, and Novalis, Breton abhorred the Nazis but would not reject German culture. Instead, he highlighted those Germans whose works most forcefully belied the Fascist programme.

Still, although Gaston Gallimard initially professed enthusiasm for Breton’s anthology, in the end he, too, would decline, and it was Léon Pierre-Quint of Sagittaire, the book’s original publisher, who ultimately reclaimed the project in April 1940. On the 29th, a relieved Breton told him: ‘You know that I had originally composed this book for Sagittaire: I’m delighted that it is now back with you. It seems to me, furthermore, that its publication at any other time would have been less fitting.’

The printed sheets came off the press on 10 June; four days later, German forces entered Paris and the Occupation began. The puppet Vichy regime was quickly established, as was a censorship board to which all forthcoming books had to be sent for clearance. Pierre-Quint duly submitted the Anthology for authorization in January 1941, but that same month the board gave its unequivocal refusal and the Anthology of Black Humour, finally printed after a four-year delay, languished for another five.

When the book was at last distributed in 1945, it was to almost total silence – hardly more than three or four notices in the papers, including a piece by ex-Surrealist Raymond Queneau, typical of the reigning attitudes, that chided Breton for his parlour anarchism. In any case, Breton, who had left France and taken wartime refuge in the United States, would not see these reactions, or his anthology in the bookstores, until after his return to Europe a year later.

Not surprisingly, the first edition soon disappeared from circulation, and for several years the book was again unavailable. A second, revised edition was issued in 1950, this time to slightly increased notice, and a ‘definitive’ one, featuring a new preface, was published shortly before Breton’s death. Only then did the Anthology of Black Humour begin to receive at least a share of the attention normally paid Breton’s works.

* * *

As of this writing, all those included in this volume, with the exception of Leonora Carrington and Gisèle Prassinos, are dead. This was not the case when Breton published the final edition, and I have acknowledged the passage of time by putting death dates in brackets for those who, when Breton died, were still alive.

As to the translations themselves, in keeping with the spirit of a collective work I have used existing versions whenever good ones were available, to preserve a diversity of voices. I have also expanded Breton’s selected bibliographies at the end of each prefatory note to account more specifically for English editions of the relevant works, if such exist.

In translating this Anthology of Black Humour, it is my hope, as it surely was Breton’s, that the samples provided here will inspire further contact with these strange, hilarious, and sobering minds.

M. P. July 1996

Foreword to the 1966 French Edition

The current, revised edition brings to the preceding one a few corrections of detail. It has deliberately not been expanded, even at the risk of leaving a few readers dissatisfied. In the perspective that initially informed this book, it is certain that the author, in the course of these past few years, could not help but see new figures emerge who emit a similar light. He particularly had to resist the temptation to include the works of Oskar Panizza, Georges Darien, G. I. Gurdjieff (as he appears in his magisterial ‘The Arousing of Thought,’ the opening chapter of Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson), Eugène Ionesco, and Joyce Mansour; but he finally chose not to, for obvious reasons. This book, published for the first time in 1940 and reprinted with a few additions in 1950, marked, as is, its era. Let us simply recall that when it first appeared, the words ‘black humour’ made no sense (unless to designate a form of banter supposedly characteristic of ‘Negroes’!). It is only afterwards that the expression took its place in the dictionary: we know what fortune the notion of black humour has enjoyed. Everything suggests that it remains full of effervescence, and is spreading as much by word of mouth (in so-called ‘Bloody Mary’ jokes) as in the visual arts (especially in the cartoons featured in certain weekly magazines) and in film (at least when it deviates from the safe path of mainstream production). My wish is that this book should remain directly linked to our era no less than to the preceding one, and that it should never be seen as some sort of constantly updated annual, a pathetic honour roll bearing no trace whatsoever of its original purpose. Kindly consider this, then, the definitive edition of the Anthology of Black Humour.

André Breton Paris, 16 May 1966

Lightning Rod

‘The preface could be called “the lightning rod”.’ Lichtenberg

‘For there to be comedy, that is, emanation, explosion, comic release,’ said Baudelaire, ‘there must be …’

Emanation, explosion: it is startling to find the same two words linked in Rimbaud, and this in the heart of a poem that is as prodigal in black humour as can be (it is, in fact, the last poem we have of his, one in which his ‘expression as buffoonish and strange as possible’ reemerges, supreme and extremely condensed, from efforts that aimed first at its affirmation, then at its negation):

‘Dream’

In the barracks stomachs grumble –How true ………………………………Emanations, explosions,An engineer: I’m the gruyere! ……………………………………

Chance encounter, involuntary recall, direct quotation? To decide once and for all, we would have to take the exegesis of this poem – the most difficult in the French language – rather far, but this exegesis has not even begun. Such a verbal coincidence is nonetheless significant in and of itself. It reveals in both poets a shared concern with the atmospheric conditions, so to speak, in which the mysterious exchange of humorous pleasure between individuals can occur – an exchange to which, over the past century and a half, a rising price has been attached, which today makes it the basis of the only intellectual commerce that can be considered high luxury.

Given the specific requirements of the modern sensibility, it is increasingly doubtful that any poetic, artistic, or scientific work, any philosophical or social system that does not contain this kind of humour will not leave a great deal to be desired, will not be condemned more or less rapidly to perish. The value we are dealing with here is not only in ascendancy over all others, but is even capable of subsuming them, to the point where a great number of these values will lose the universal respect they now enjoy. We are touching upon a burning subject; we are headed straight into a land of fire: the gale winds of passion are alternately with us and against us from the moment we consider lifting the veil from this type of humour, whose manifest products we have nonetheless managed to isolate, with a unique satisfaction, in literature, art, and life. Indeed, we have the sense – if only obscurely – of a hierarchy in which the total possession of humour would assure man the highest rung; but to this very degree, any global definition of humour eludes us, and will probably continue to elude us for some time to come, in virtue of the principle that ‘man naturally tends to deify what is at the limit of his understanding.’ Just as ‘high initiation (which only a few elite spirits have reached), as the ultimate postulate of High Science, hardly teaches us how to reason with Divinity’1 (the High Kabbalah, reduction of High Science to an earthly level, is jealously kept secret by the initiates), there can be no question of explaining humour and making it serve didactic ends. One might just as well try to extract a moral for living from suicide. ‘There is nothing,’ it has been said, ‘that intelligent humour cannot resolve in gales of laughter, not even the void … Laughter, as one of humanity’s most sumptuous extravagances, even to the point of debauchery, stands at the lip of the void, offers us the void as a pledge.’2 We can imagine the advantage that humour would be liable to take of its very definition, and especially of this definition.

Under these conditions, we shouldn’t wonder that the various surveys on the subject have so far yielded only the most paltry results. For one of them, poorly executed in the November 1921 issue of Aventure, Paul Valéry wrote: ‘The word humour cannot be translated. If it could, the French would not employ it [in its English form]. But employ it they do, precisely because of the indeterminacy that they read into it, which makes it a very useful word when trying to account for taste. Every statement in which it figures alters its meaning, so that this very meaning is rigorously no more than the statistical totality of all the sentences that contain it, or that eventually will contain it.’ In the final analysis, this stance of total reticence is still preferable to the verbosity demonstrated by Mr Aragon, who in his Treatise on Style seems to have taken it into his head to exhaust the subject (one might say cloud the issue); but humour was not so forgiving, and, subsequently, I can think of no one whom it has abandoned more radically. ‘You want the rest of humour’s anatomical parts? All right, if you look at that fellow who is raising his hand, Suh? to ask permission to speak, you’ve got the head of hair. The eyes: two holes for mirrors. The ears: shooting lodges. The right hand called symmetry represents the law courts, the left hand is the arm of a one-armed person missing the right … Humour is what soup, chickens and symphony orchestras lack. On the other hand, road pavers, elevators, and crush hats have it … It has been pointed out in kitchen utensils, it has been known to appear in bad taste, and it has its winter quarters in fashion … Where is it running to? To the optical effect. Its home? The Petit Saint-Thomas. Its favourite writers? A certain Binet-Valmer. Its weakness? The sun like a fried egg in the evening sky. It does not scorn adopting a serious tone. All in all, it bears a strong resemblance to the foresight of a rifle,’ etc. A good grade-A senior paper, which takes this theme as it might any other, and which has only an external view of humour. Once again, all this juggling merely begs the question. On the other hand, the subject has been handled with rare precision by Léon Pierre-Quint, who in Le Comte de Lautréamont et Dieu presents humour as a way of affirming, above and beyond ‘the absolute revolt of adolescence and the internal revolt of adulthood,’ a superior revolt of the mind.

For there to be humour … The problem remains posed. Still, we can credit Hegel with having made humour take a giant step forward into the domain of knowledge when he raised it to the concept of objective humour. ‘The fundamental principle of Romantic art,’ he said, ‘is the concentration of the soul upon itself. On finding that the external world does not perfectly respond to its innermost nature, the soul turns away from it. This opposition was developed in the period of Romantic art, to the point where we have seen interest be paid sometimes to the accidents of the external world, sometimes to the whims of personality. But, now, if that interest goes so far as to absorb the mind in external contemplation, and if at the same time humour, while maintaining its subjective and reflective character, lets itself be captivated by the object and its real form, we obtain in this penetration a humour that is in a certain sense objective.’ Elsewhere,3 I stated that the black sphinx of objective humour could not avoid meeting, on the dust-clouded road of the future, the white sphinx of objective chance, and that all subsequent human creation would be the fruit of their embrace.

Let us note in passing that the position Hegel assigns the various arts (poetry leads them all as the only universal art; it patterns their behaviour on its own, insofar as it is the only art that can represent the successive situations of life) suffices to explain why the kind of humour at issue here began appearing in poetry much earlier than it did in painting, for example. Satiric and moralizing intentions exert a degrading influence on almost every work of the past that, in some way, has been inspired by that kind of humour, threatening to push these works into caricature. At most, we would be tempted to make an occasional exception for Hogarth or Goya, and to reserve judgment about others in whose work humour can be sensed but at best remains hypothetical – such as in the quasi-totality of Seurat’s painted opus. It would seem that, in visual art, we must consider the triumph of humour in its pure and manifest state a much more recent phenomenon, and recognize as its first practitioner of genius the Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada. In his admirable ‘popular’ style woodcuts, Posada brought to life all the upheavals of the 1910 revolution (the ghosts of Villa and Fierro should be studied alongside these images, for a possible passage from speculative humour to action – Mexico, moreover, with its splendid funeral toys, stands as the chosen land of black humour). Since then, this kind of humour has acted in painting as if it were on conquered territory. Its black grass ceaselessly ripples wherever the horse of Max Ernst, ‘the Bride of the Wind,’ has passed. If we limit ourselves to books, there is in this regard nothing more accomplished, more exemplary than his three ‘collage’ novels: The Hundred Headless Woman, A Little Girl Dreams of Taking the Veil, and Une Semaine de bonté ou les Sept Eléments capitaux [A Week of Goodness, or the Seven Deadly Elements].

Cinema, insofar as it not only, like poetry, represents the successive stages of life, but also claims to show the passage from one stage to the next, and insofar as it is forced to present extreme situations to move us, had to encounter humour almost from the start. The early comedies of Mack Sennett, certain films of Chaplin’s (The Adventurer, The Pilgrim), and the unforgettable ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle and ‘Fuzzy’ (Al St John) command the line that should by rights lead to the midnight sunbursts that are Million Dollar Legs and Animal Crackers, and to those excursions to the bottom of the mental grotto – Fingal’s Cave as much as Pozzuoli’s crater – that are Buñuel and Dalí’s Un Chien andalou and L’Age d’or, by way of Picabia’s Entr’acte.

‘It is now time,’ says Freud, ‘to acquaint ourselves with some of the characteristics of humour. Like wit and the comic, humour has in it a liberating element. But it has also something fine and elevating, which is lacking in the other two ways of deriving pleasure from intellectual activity. Obviously, what is fine about it is the triumph of narcissism, the ego’s victorious assertion of its own invulnerability. It refuses to be hurt by the arrows of reality or to be compelled to suffer. It insists that it is impervious to wounds dealt by the outside world, in fact, that these are merely occasions for affording it pleasure.’ Freud gives this common, but adequate, example: the condemned man being led to the gallows on a Monday who observes, ‘What a way to start the week!’ We know that at the end of his analysis of humour, he sees it as a mode of thought that aims at saving itself the expenditure of feeling required by pain. ‘Without quite knowing why, we attribute to this less intensive pleasure a high value: we feel it to have a peculiarly liberating and elevating effect.’ According to him, the secret of the humorous attitude would rest on the ability that certain individuals have, in cases of serious alarm, to displace the psychic accent away from the ego and onto the superego, the latter being genetically conceived as heir to the parental function (‘it often holds the ego in strict subordination, and still actually treats it as the parents – or the father – treated the child in his early years’). I thought it might be interesting to confront this thesis with a certain number of individual attitudes that reveal humour, and with some texts in which this humour has been given its highest degree of literary expression. In order to reduce them to a common, fundamental idea, I thought it best to employ Freudian terminology in my account, without this dispelling the reservations caused by Freud’s necessarily artificial distinction between the id, the ego, and the superego.

I will not deny a considerable partiality in the choice of texts, all the more so in that such a frame of mind seems the only one appropriate to the subject at hand. My greatest fear in this case, my only cause for regret, would be not to have proven exacting enough. To take part in the black tournament of humour, one must in fact have weathered many eliminations. Black humour is hemmed in by too many things, including stupidity, sceptical sarcasm, light-hearted jokes … (the list is long). But it is the mortal enemy of sentimentality, which seems to lie perpetually in wait – sentimentality that always appears against a blue background – and of a certain short-lived whimsy, which too often passes itself off as poetry, vainly persists in inflicting its outmoded artifices on the mind, and no doubt has little time left in which to lift towards the sun, from amid the poppy seeds, its crowned crane’s head.

1939

.

1. Armand Petitjean, Imagination et Réalisation (Paris, 1936).

2. Pierre Piobb, Les Mystères des Dieux (Paris, 1909).

3. ‘Surrealist Situation of the Object,’ in Political Position of Surrealism (1935). [English translation in Manifestoes of Surrealism (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969).]

ANTHOLOGY OF BLACK HUMOUR

Jonathan Swift

1667–1745

When it comes to black humour, everything designates him as the true initiator. In fact, it is impossible to coordinate the fugitive traces of this kind of humour before him, not even in Heraclitus and the Cynics or in the works of the Elizabethan dramatic poets. Swift’s incontestable originality, the perfect unity of his production viewed from the angle of the very special and almost unprecedented emotion it elicits, the unsurpassable character, from this same viewpoint, of his many varied successes historically justify his being presented as the first black humorist. Contrary to what Voltaire might have said, Swift was in no sense a ‘perfected Rabelais.’ He shared to the smallest possible degree Rabelais’s taste for innocent, heavy-handed jokes and his constant drunken good humour. In the same way, he stood opposite Voltaire in his entire way of reacting to the spectacle of life, as their two death masks so expressively attest: one bearing a perpetual snicker, the mask of a man who grasped things by reason and never by feeling, and who enclosed himself in scepticism; the other impassive, glacial, the mask of a man who grasped life in a wholly different way, and who was constantly outraged. It has been remarked that Swift ‘provokes laughter, but does not share in it.’ It is precisely at this price that humour, in the sense we understand it, can externalize the sublime element that, according to Freud, is inherent in it, and transcend the merely comic. Again in this respect, Swift can rightfully be considered the inventor of ‘savage’ or ‘gallows’ humour. The profoundly singular turn of his mind inspired in him a series of diversions and reflections on the order of ‘The Lady’s Dressing Room’ and the ‘Meditation Upon a Broom-Stick,’ which partake of a remarkably modern spirit, and are responsible in and of themselves for the fact that perhaps no body of work is less out of date.

Swift’s eyes were, it seems, so changeable that they could turn from light blue to black, from the candid to the terrible. This variation perfectly matches his ways of feeling: ‘I have ever,’ he says, ‘hated all nations, professions, and communities, and all my love is towards individuals … But principally I hate and detest that animal called man, although I heartily love John, Peter, Thomas, and so forth.’ The man who more than anyone despised the human race was no less possessed by a frantic need for justice. He wandered through the ministries of Dublin and his little vicarage in Laracor, anxious to know whether he was meant to look after his willows and enjoy the playing of his trout or to meddle with affairs of state. He did meddle with them, moreover, as if despite himself and on several occasions, in the most active and effective way. ‘That Irishman,’ it was said, ‘who considers himself an exile in his own country, has yet to reside elsewhere; that Irishman, always ready to speak ill of Ireland, risked for her his fortune, his freedom, his life, and saved her, for almost a century, from the slavery with which England threatened it.’ In the same way, the misogynistic author of the ‘Letter to a Young Lady on Her Marriage’ was doomed in his own life to the worst emotional complications: three women, Varina, Stella, and Vanessa, fought over his love, and, if he broke with the first in a shower of insults, he was condemned to see the other two tear each other apart and die without having forgiven him. It was to this priest that one of them wrote: ‘Was I an Enthusiast still you’d be the Deity I should worship.’ From one end of his life to the other, his misanthropy was the only disposition that never altered, and that events never belied. He had said one day, pointing to a tree struck by lightning, ‘I shall be like that tree; and die first at the top.’ As if for having wished to reach ‘the sublime and refined point of felicity … the possession of being well-deceived; the serene peaceful state of being a fool among knaves,’ he saw himself decline, in 1736, into a mental enfeeblement whose progress he was able to follow for ten years, with horrible lucidity. In his will, he left ten thousand pounds to build a hospital for the insane.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: A Tale of a Tub, 1704. The Works of Sir William Temple, 1720. Gulliver’s Travels, 1726. Miscellanies in Prose and Verse, 1727–1735. Directions to Servants, 1751, etc.

.

DIRECTIONS TO SERVANTS

Masters and ladies are usually quarrelling with the servants for not shutting the doors after them; but neither masters nor ladies consider that those doors must be open before they can be shut, and that the labour is double to open and shut the doors; therefore the best, and shortest, and easiest way is to do neither. But if you are so often teased to shut the door, that you cannot easily forget it, then give the door such a clap as you go out, as will shake the whole room, and make every thing rattle in it, to put your master and lady in mind that you observe their directions.

If you find yourself to grow into favour with your master or lady, take some opportunity in a very mild way to give them warning; and when they ask the reason, and seem loth to part with you, answer, that you would rather live with them than any body else, but a poor servant is not to be blamed if he strives to better himself; that service is no inheritance; that your work is great, and your wages very small. Upon which, if your master hath any generosity, he will add five or ten shillings a quarter rather than let you go: But if you are balked, and have no mind to go off, get some fellow-servant to tell your master that he had prevailed upon you to stay.

Whatever good bits you can pilfer in the day, save them to junket with your fellow-servants at night, and take in the butler, provided he will give you drink.

Write your own name and your sweetheart’s, with the smoke of a candle, on the roof of the kitchen or the servants’ hall, to show your learning.

If you are a young, sightly fellow, whenever you whisper your mistress at the table, run your nose full in her cheek, or if your breath be good, breathe full in her face; this I have known to have had very good consequences in some families.

Never come till you have been called three or four times; for none but dogs will come at the first whistle; and when the master calls ‘Who’s there?’ no servant is bound to come; for Who’s there is no body’s name.

• • •

Some nice ladies who are afraid of catching cold, having observed that the maids and fellows below stairs often forget to shut the door after them, as they come in or go out into the back yards, have contrived that a pulley and a rope with a large piece of lead at the end, should be so fixed, as to make the door shut of itself, and require a strong hand to open it; which is an immense toil to servants whose business may force them to go in and out fifty times in a morning: But ingenuity can do much, for prudent servants have found out an effectual remedy against this insupportable grievance, by tying up the pulley in such a manner that the weight of the lead shall have no effect; however, as to my own part, I would rather choose to keep the door always open, by laying a heavy stone at the bottom of it.

The servants’ candlesticks are generally broken, for nothing can last for ever. But you may find out many expedients; you may conveniently stick your candle in a bottle, or with a lump of butter against the wainscot, in a powder-horn, or in an old shoe, or in a cleft stick, or in the barrel of a pistol, or upon its own grease on a table, in a coffeecup, or a drinking-glass, a horn can, a teapot, a twisted napkin, a mustard-pot, an ink-horn, a marrowbone, a piece of dough, or you may cut a hole in the loaf, and stick it there.

When you invite the neighbouring servants to junket with you at home in an evening, teach them a peculiar way of tapping or scraping at the kitchen-window, which you may hear, but not your master or lady, whom you must take care not to disturb or frighten at such unseasonable hours.

Lay all faults on a lap-dog, a favourite cat, a monkey, a parrot, a child, or on the servant who was last turned off; by this rule you will excuse yourself, do no hurt to any body else, and save your master or lady from the trouble and vexation of chiding.

When you want proper instruments for any work you are about, use all expedients you can invent rather than leave your work undone. For instance, if the poker be out of the way, or broken, stir up the fire with the tongs; if the tongs be not at hand, use the muzzle of the bellows, the wrong end of the fire-shovel, the handle of the fire-brush, the end of a mop, or your master’s cane. If you want paper to singe a fowl, tear the first book you see about the house. Wipe your shoes, for want of a clout, with the bottom of a curtain, or a damask napkin. Strip your livery lace for garters. If the butler wants a jordan, he may use the great silver cup.

There are several ways of putting out candles, and you ought to be instructed in them all: You may run the candle end against the wainscot, which puts the snuff out immediately; you may lay it on the floor, and tread the snuff out with your foot; you may hold it upside down, until it is choked with its own grease; or cram it into the socket of the candlestick; you may whirl it round in your hand till it goes out: when you go to bed, after you have made water, you may dip the candle end into the chamber-pot: you may spit on your finger and thumb, and pinch the snuff until it goes out. The cook may run the candle’s nose into the meal-tub, or the groom into a vessel of oats, or a lock of hay, or a heap of litter; the housemaid may put out her candle by running it against a looking-glass, which nothing cleans so well as candle-snuff; but the quickest and best of all methods is to blow it out with your breath, which leaves the candle clear, and readier to be lighted.

* * *

A MODEST PROPOSAL

for preventing the children of poor people from being a burthen to their parents or country, and for making them beneficial to the public.

It is a melancholy object to those who walk through this great town, or travel in the country, when they see the streets, the roads, and cabin-doors crowded with beggars of the female sex, followed by three, four, or six children, all in rags, and importuning every passenger for an alms. These mothers, instead of being able to work for their honest livelihood, are forced to employ all their time in strolling, to beg sustenance for their helpless infants, who, as they grow up, either turn thieves for want of work, or leave their dear Native Country to fight for the Pretender in Spain, or sell themselves to the Barbadoes.

I think it is agreed by all parties that this prodigious number of children, in the arms, or on the backs, or at the heels of their mothers, and frequently of their fathers, is in the present deplorable state of the kingdom a very great additional grievance; and therefore whoever could find out a fair, cheap, and easy method of making these children sound useful members of the commonwealth would deserve so well of the public as to have his statue set up for a preserver of the nation.

But my intention is very far from being confined to provide only for the children of professed beggars; it is of a much greater extent, and shall take in the whole number of infants at a certain age who are born of parents in effect as little able to support them as those who demand our charity in the streets.

As to my own part, having turned my thoughts, for many years, upon this important subject, and maturely weighed the several schemes of other projectors, I have always found them grossly mistaken in their computation. It is true a child, just dropped from its dam, may be supported by her milk for a solar year with little other nourishment, at most not above the value of two shillings, which the mother may certainly get, or the value in scraps, by her lawful occupation of begging, and it is exactly at one year old that I propose to provide for them, in such a manner as, instead of being a charge upon their parents, or the parish, or wanting food and raiment for the rest of their lives, they shall, on the contrary, contribute to the feeding and partly to the clothing of many thousands.

There is likewise another great advantage in my scheme, that it will prevent those voluntary abortions, and that horrid practice of women murdering their bastard children, alas, too frequent among us, sacrificing the poor innocent babes, I doubt, more to avoid the expense than the shame, which would move tears and pity in the most savage and inhuman breast.

The number of souls in this kingdom being usually reckoned one million and a half, of these I calculate there may be about two hundred thousand couple whose wives are breeders, from which number I subtract thirty thousand couples who are able to maintain their own children, although I apprehend there cannot be so many under the present distresses of the kingdom, but this being granted, there will remain an hundred and seventy thousand breeders. I again subtract fifty thousand for those women who miscarry, or whose children die by accident or disease within the year. There only remain an hundred and twenty thousand children of poor parents annually born: The question therefore is, how this number shall be reared, and provided for, which, as I have already said, under the present situation of affairs, is utterly impossible by all the methods hitherto proposed, for we can neither employ them in handicraft, or agriculture; we neither build houses (I mean in the country), nor cultivate land: they can very seldom pick up a livelihood by stealing till they arrive at six years old, except where they are of towardly parts, although, I confess they learn the rudiments much earlier, during which time they can however be properly looked upon only as probationers, as I have been informed by a principal gentleman in the County of Cavan, who protested to me that he never knew above one or two instances under the age of six, even in a part of the kingdom so renowned for the quickest proficiency in that art.

I am assured by our merchants that a boy or a girl, before twelve years old, is no saleable commodity, and even when they come to this age, they will not yield above three pounds, or three pounds and half-a-crown at most on the Exchange, which cannot turn to account either to the parents or the kingdom, the charge of nutriment and rags having been at least four times that value.

I shall now therefore humbly propose my own thoughts, which I hope will not be liable to the least objection.

I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food, whether stewed, baked, or boiled, and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee, or a ragout.

I do therefore humbly offer it to public consideration, that of the hundred and twenty thousand children already computed, twenty thousand may be reserved for breed, whereof only one fourth part to be males, which is more than we allow to sheep, black-cattle, or swine, and my reason is that these children are seldom the fruits of marriage, a circumstance not much regarded by our savages, therefore one male will be sufficient to serve four females. That the remaining hundred thousand may at a year old be offered in sale to the persons of quality, and fortune, through the kingdom, always advising the mother to let them suck plentifully in the last month, so as to render them plump, and fat for a good table. A child will make two dishes at an entertainment for friends, and when the family dines alone, the fore or hind quarter will make a reasonable dish, and seasoned with a little pepper or salt will be very good boiled on the fourth day, especially in winter.

I have reckoned upon a medium, that a child just born will weigh 12 pounds, and in a solar year if tolerably nursed increaseth to 28 pounds.

• • •

A very worthy person, a true lover of this country, and whose virtues I highly esteem, was lately pleased, in discoursing on this matter, to offer a refinement upon my scheme. He said that many gentlemen of this kingdom, having of late destroyed their deer, he conceived that the want of venison might be well supplied by the bodies of young lads and maidens, not exceeding fourteen years of age, nor under twelve, so great a number of both sexes in every country being now ready to starve, for want of work and service: and these to be disposed of by their parents if alive, or otherwise by their nearest relations. But with due deference to so excellent a friend, and so deserving a patriot, I cannot be altogether in his sentiments; for as to the males, my American acquaintance assured me from frequent experience that their flesh was generally tough and lean, like that of our schoolboys, by continual exercise, and their taste disagreeable, and to fatten them would not answer the charge. Then as to the females, it would, I think with humble submission, be a loss to the public, because they soon would become breeders themselves: And besides, it is not improbable that some scrupulous people might be apt to censure such a practice (although indeed very unjustly) as a little bordering upon cruelty, which, I confess, hath always been with me the strongest objection against any project, however so well intended.

• • •

I think the advantages by the proposal which I have made are obvious and many, as well as of the highest importance.

For first, as I have already observed, it would greatly lessen the number of Papists, with whom we are yearly over-run, being the principal breeders of the nation, as well as our most dangerous enemies, and who stay at home on purpose with a design to deliver the kingdom to the Pretender, hoping to take their advantage by the absence of so many good Protestants, who have chosen rather to leave their country than stay at home, and pay tithes against their conscience to an Episcopal curate.

Secondly, The poorer tenants will have something valuable of their own, which by law be made liable to distress, and help to pay their landlord’s rent, their corn and cattle being already seized, and money a thing unknown.

Thirdly, Whereas the maintenance of an hundred thousand children, from two years old, and upwards, cannot be computed at less than ten shillings a piece per annum, the nation’s stock will be thereby increased fifty thousand pounds per annum, besides the profit of a new dish, introduced to the tables of all gentlemen of fortune in the kingdom, who have any refinement in taste, and the money will circulate among ourselves, the goods being entirely of our own growth and manufacture.

Fourthly, The constant breeders, besides the gain of eight shillings sterling per annum, by the sale of their children, will be rid of the charge of maintaining them after the first year.

Fifthly, This food would likewise bring great custom to taverns, where the vintners will certainly be so prudent as to procure the best receipts for dressing it to perfection, and consequently have their houses frequented by all the fine gentlemen, who justly value themselves upon their knowledge in good eating; and a skilful cook, who understands how to oblige his guests, will contrive to make it as expensive as they please.

Sixthly, This would be a great inducement to marriage, which all wise nations have either encouraged by rewards, or enforced by laws and penalties. It would increase the care and tenderness of mothers toward their children, when they were sure of a settlement for life, to the poor babes, provided in some sort by the public to their annual profit instead of expense. We should see an honest emulation among the married women, which of them could bring the fattest child to the market, men would become as fond of their wives, during the time of their pregnancy, as they are now of their mares in foal, their cows in calf, or sows when they are ready to farrow, nor offer to beat or kick them (as it is too frequent a practice) for fear of a miscarriage.

* * *

A MEDITATION UPON A BROOM-STICK

This single stick, which you now behold ingloriously lying in that neglected corner, I once knew in a flourishing state in a forest; it was full of sap, full of leaves, and full of boughs; but now, in vain does the busy art of man pretend to vie with nature, by tying that withered bundle of twigs to its sapless trunk; ’tis now, at best, but the reverse of what it was, a tree turned upside down, the branches on the earth, and the root in the air; ’tis now handled by every dirty wench, condemned to do her drudgery, and, by a capricious kind of fate, destined to make other things clean, and be nasty itself: at length, worn to the stumps in the service of the maids, it is either thrown out of doors, or condemned to the last use, of kindling a fire. When I beheld this I sighed, and said within myself, Surely man is a Broomstick! Nature sent him into the world strong and lusty, in a thriving condition, wearing his own hair on his head, the proper branches of this reasoning vegetable, until the axe of intemperance has lopped off his green boughs, and left him a withered trunk: he then flies to art, and puts on a periwig, valuing himself upon an unnatural bundle of hairs, (all covered with powder,) that never grew on his head; but now, should this our broomstick pretend to enter the scene, proud of those birchen spoils it never bore, and all covered with dust, though the sweepings of the finest lady’s chamber, we should be apt to ridicule and despise its vanity. Partial judges that we are of our own excellencies, and other men’s defaults.

But a broomstick, perhaps, you will say, is an emblem of a tree standing on its head; and pray what is man, but a topsyturvy creature, his animal faculties perpetually mounted on his rational, his head where his heels should be, grovelling on the earth; and yet, with all his faults, he sets up to be a universal reformer and corrector of abuses, a remover of grievances, rakes into every slut’s corner of Nature, bringing hidden corruption to the light, and raises a mighty dust where there was none before; sharing deeply all the while in the very same pollutions he pretends to sweep away: his last days are spent in slavery to women, and generally the least deserving, till, worn out to the stumps, like his brother besom, he is either kicked out of doors, or made use of to kindle flames for others to warm themselves by.

* * *

THOUGHTS ON VARIOUS SUBJECTS, MORAL AND DIVERTING

If a man will observe as he walks the streets, I believe he will find the merriest countenances in mourning coaches.

*

Venus, a beautiful, good-natured lady, was the goddess of love; Juno, a terrible shrew, the goddess of marriage; and they were always mortal enemies.

*