8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In 2008 a faded typescript was discovered in a suitcase in the attic of one of Martin Freud's grandchildren. It was a satirical novel about the Second World War written by Sigmund Freud's son Martin, but never published and apparently forgotten about. Freud and his family had escaped from Nazi-occupied Vienna in 1938, narrowly avoiding losing everything, including their lives. Arriving in England, Martin, formerly an eminent lawyer in Vienna, was interned as an 'enemy alien,' and later ran a shop near the British Museum (his son, Walter, fought for the British in the SOE during the war). It is known that Martin wrote numerous poems and pieces of fiction, but the only books he ever published were a fictionalised account of his experiences during the First World War, Parole d'Honneur, in 1939 and an autobiography, Glory Reflected, in 1957. Now translated into English and published for the first time, Any Survivors? is not only a satirical and dramatic novel about a refugee who returns to Hitler's Germany as a rather inept spy, but also the testament of a man who lived through the most dramatic moments of this period as part of a famous and fascinating family.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

ANY SURVIVORS?

ANY SURVIVORS?

A LOST NOVEL OF WORLD WAR II

MARTIN FREUD

TRANSLATED BY ANETTE FUHRMEISTER EDITED BY HELEN FRY

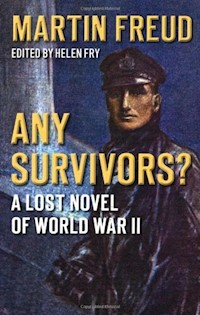

Front Cover: U-boat commander (Mary Evans Picture Library)

First published 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

© Martin Freud, 2010

Translation © Anette Fuhrmeister

Preface © Helen Fry

The right of Martin Freud, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7596 7

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7595 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Preface

Prologue

1 Lights Out!

2 Sealed Order

3 Counter-espionage on Holiday

4 The New Role

5 Tightrope Walk in the Dark

6 In the Deep

7 Dangerous Game

8 Arrest

9 The Nightmare

10 Division of the Loot

11 The Gift

12 Kraft Durch Freude

13 Health Resort, Headquarters

14 The Königssee

15 A Guest at Berghof

16 The Relentless One

Translator's Notes

PREFACE

It is every historian's dream to stumble across something significant in a battered old case in a forgotten attic. However, that is precisely what happened with Martin Freud's unpublished novel Any Survivors? I discovered it quite by chance whilst rummaging through papers which the family had lent me for writing Freuds’ War. The manuscript was amongst several papers in a tatty briefcase, both of which had seen better days. The novel, which ran to over 330 typed pages, was written in German except for the opening scene which was in English. When I read the opening scene, I wanted to read on – who was the survivor pulled out of the freezing water by men on a British destroyer? And what was his connection to the U-boat crew that had perished? Whilst my German was not sufficient to understand the bulk of the text, I knew already from my study of Martin Freud's life that much of what he had written in the past was strongly autobiographical and I suspected that this might be true of this novel which is set in the Second World War. During his lifetime Martin Freud published two books: the first his autobiography Glory Reflected and second, his novel Parole d’Honneur which is heavily based on his experiences in the Austro-Hungarian Royal Horse Artillery in the First World War.

The manuscript has been translated from the German and edited in such a way as to keep closely to the style and ambiance of the original.

Martin Freud was the eldest son of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. Born in Vienna on 7 December 1889, Martin grew up in an environment where he was aware of his father's international reputation and fame, and spoke of being ‘content to bask in reflected glory’. Martin was close to his father, whom he described as having ‘ein froehliches herz’ (a merry heart). From 1914 until 1918 he fought for his country on the Russian and Italian front lines during the First World War, during which time he was awarded seven medals for bravery, two of which were Military Crosses. Just days before the Armistice was signed in November 1918 he was taken as a prisoner of war by the British in Italy and spent nearly a year in an Italian prisonerof-war camp until the summer of 1919. When he was finally released he returned to Vienna and trained as a lawyer. On his thirtieth birthday in 1919 he married Ernestine Drucker and settled into married life. They had two children: Anton Walter (1921) and Sophie (1924). During the 1930s Martin ran his father's press as Director of International Psychoanalytical Press (Verlag). The offices of the Verlag had moved to 7 Berggasse, just down the street from the family home. In March 1938 Freud's world and that of Austrian Jews was turned upside down when Hitler marched his troops over the border into Austria and annexed the country. After a period of house arrest and two tense months in which it was not obvious the family would get out, visas were finally secured. Martin left for England a month before his parents and settled in London. His marriage had deteriorated and so Martin and Esti separated. Esti stayed in France with their daughter Sophie until forced to flee from the Nazis again, eventually settling in America.

With the outbreak of war in September 1939, Martin and son Walter (now in England) were classified as ‘enemy aliens’. In June 1940 Martin was interned by the British government at Huyton near Liverpool, from where a few months later he enlisted in the British army's Pioneer Corps. Disillusioned with life in a labour corps, he was eventually invalided out in June 1941 and took up reserved war work travelling the country as an auditor for the National Dock Labour Corporation. It was during this particular work that he may have gained the inspiration which forms the basis of parts of this novel. This is not an unreasonable assumption because most of his unpublished short stories which exist amongst the family papers are largely based on his personal experiences; likewise his autobiographical first novel Parole d’Honneur. Martin worked for the National Dock Labour Corporation until c. 1948. When he left, he opened a tobacconist shop near the British Museum. Later he moved to Hove in Sussex where he lived with his partner Margaret, until his death on 25 April 1967. His ashes are interred in the family section at Golders Green crematorium.

During his lifetime Martin had no success in getting Any Survivors? published. However, four decades after his death this has come to fruition and is a welcome addition to the Freud family contribution to the literary world.

Dr Helen Fry, author of Freuds’ War

PROLOGUE

‘Are there any survivors? Any survivors?’ asked the commander of the British destroyer.

‘Just the one, sir. A young sailor. He is conscious and unhurt. Spitting a little blood, the poor chap. I don't think his lungs could cope with the Davisapparat.’

‘What is he saying?’

‘Well sir, he won't stop talking. His English is terrible but he insists he is not part of the U-boat crew.’

‘What a cheek! He appeared at exactly the spot where we sank the U-boat. And who does he pretend to be? A cruise passenger or a leisure traveller …?’

‘Sir, I don't think he means any harm. He's just expressing himself a little awkwardly in our language. He's saying: “I am supposed to be a member of the crew but I am not a member.” He may well be confused from the shock of being submerged in the icy water. He keeps repeating that he must tell his story. Would you like to hear it, sir?’

‘Nonsense! Not now. The man should be taken to quarters, given some warm clothes and put to bed with a hot toddy. Tomorrow, as soon as we land, he will be taken to hospital.’

‘Yes sir!’

What a dirty trick to pretend he is not a member of the crew.

Well, here is the story …

1

LIGHTS OUT!

September 1939

I was thinking … and when I was thinking simple things, I thought in English. I had been living in London for over a year. Although I was not exactly a maharajah in my home town, I was at least a young man with a profession and the opportunity to progress in my career. A dental technician is a useful and reputable occupation and even well paid. And here I was now living as a refugee in England with no work permit, forgetting the little I had learnt in my previous life. People treated me like one half of a pair of gloves found lying on the street – of no commercial value.

I'm sure my mother was right to persuade me to leave the country. I can divulge only a little of my past as my mother is still in my home country and anything I say, write down or do, could harm her. I will say only this much: I am from a country that used to be free and happy until Hitler came along and forced us into submission with arms and no resistance.

I received some aid here in London but not to the extent that I could live it up in the Grosvenor House or even anywhere in Mayfair; I was living in King's Cross in a basic boarding house. Unfortunately it so happened that I was the only young man in the house. The other guests, mainly elderly ladies, were also from countries that Hitler had already occupied – or was going to in the near future. The more prudent amongst us did not wait but emigrated well before he seized power.

My room was a tiny garret on the top floor, just big enough to sleep in but with no real space in which to live during the day. Once, when I was in the communal living room, I had no time to relax because all the ladies started bossing me around and asking me to do things for them. As they were older than I, and female too, they believed this was their right. If they had their own way I might have spent all day on ladders, hanging blackout curtains and filling gaps with black paper to achieve perfect darkness.

I should have started with the fact that war had just broken out. As I headed for the lounge, I could overhear one of the ladies saying: ‘Where is that insolent lazy-bones hiding?’ It was one of the elderly ladies with a very deep voice. ‘I’ve been looking for him all day. I want him to go to the W.W. for me to get some more drawing pins before they run out.’

‘I don't know what you mean,’ said a lady with a much higher voice. ‘I don't think he's insolent. He is modest and shy and often looks at one with his kind eyes. I tell you it makes me feel quite motherly towards him.’

‘That's only when he wants something from you; some toast made or some trousers ironed.’ Now this was slightly unfair in my opinion; it was over a week since anyone had made me any toast or ironed my trousers.

I came into the room. ‘Please excuse me,’ I said. ‘You were speaking about me.’

I don't think I put that quite right; I should have said ‘Excuse me for listening in’ but I wanted to be as polite as possible. My aim was to take a book from the shelf, and there was the danger that they would come up with another thing for me to do, as in: ‘Leave the book there and go and fill some sandbags instead.’

All this took place yesterday. As I came into the room today, there was no one there. It was unusually quiet. I took out a book on Charlotte Corday since I was researching the history of famous murderers of tyrants. Not that I wanted to murder a tyrant myself. Personally, I didn't feel I could murder anyone, even less a tyrant, but I was interested in the method: how to plan grand deeds and how to execute them, peaceful deeds that are not murderous ones.

I was daydreaming, pleasantly seated on the biggest and most comfortable sofa. The only good reading light was to my left. The Charlotte Corday book was on my lap, with my thumb marking the spot where the beautiful murderess buys a kitchen knife from an ironmonger near the Palais Royal at the crack of dawn. My legs were dangling down the side of the seat and to my right there was a glass of water. I gazed at the cheap clock on the mantelpiece, its hands gratifyingly inching towards 7 p.m. Any minute the dinner gong would sound. I was only on half board, entitled to breakfast and dinner. This arrangement was more appropriate for those who worked and lunched in the city. Shouldn't the gong have sounded by now? Earlier today there had been some unrest: furniture was shifted, doors banged and phones rang. The silence now was pleasant in contrast.

I heard footsteps and quickly sat up straight, removing my legs from the cushion. It was only the chambermaid with whom I was having a minor feud. My circumstances dictated that I could not tip her but that was no reason for her to treat me with contempt and not speak to me in her mother tongue, which was Scottish. She came in, took the clock off the mantelpiece, stuck it under her arm and left the room without saying a word. Aha, I thought, we’re having soft-boiled eggs for dinner or something that needs to be timed accurately. She came back in. This time she took my half-empty glass of water without a word of apology and disappeared again. Aha, I thought. Frau Pokorny has visitors and they are serving orangeade for which they need more glasses. Frau Pokorny lived comfortably – her daughters were married and living in the United States and sent her money regularly. The boarding house charged 6d per glass which was surely a 100 per cent mark-up since sugar and fruit were still cheap.

The girl came back again, this time approaching me directly. I clutched my book resolutely. She grabbed the reading lamp, unscrewed the light bulb and stuck it in her apron pocket. She used a cloth to hold the bulb so as not to burn her hands; then left me behind in complete darkness. This seemed to me to overstep the mark of what I could endure. I was a paying customer even if I was being helped financially. Besides, I was no more than three days behind with the rent. Ready to complain to the chambermaid, I carefully felt my way out of the room.

The hallway was full of boxes. The chambermaid was now unscrewing the bulbs from the lamps in reception and filling a basket with them. The doors to the bedroom on the ground floor were wide open and all the rooms empty. There was no sign of the landlady. On the desk I found a letter addressed to me. It was the weekly bill which was normally due in four days time. I owed 15/4 and this morning's breakfast was the last meal they were charging me for. Underneath the bill I found the following:

Dear Mr …, I trust that you will pay the outstanding amount of 15/4 as soon as you receive your next benefit payment. We are closing here and are moving to a new site. I am only able to take the ladies with me, as we are already at full capacity. I'm sure you will find somewhere else to stay.

Yours sincerely,

…

It was not only water and light that had been taken from me; it was now the roof over my head. I could just about see into the kitchen downstairs. The crockery and cutlery was all packed up and there was no sign of the gong either.

‘When are you closing up?’ I asked the chambermaid. She shrugged and remained silent. I may as well have spoken to her in Farsi. The sooner I left, the sooner I would find somewhere else to stay. Two men came in and started to remove the suitcases. Emergency lighting on the stairs enabled me to make my way up to my room to pack. Only when I had opened and closed all the cupboard drawers did I realise that there was nothing I could pack because I had no possessions. There was no point in taking a pile of old papers and magazines. My spare shirt and second pair of socks were in the wash with little chance of retrieving them now that I owed laundry money. I put on my shoes with the bitter feeling that horses and cows could grow new hooves but the heels on my shoes would not grow back. They would only wear down further. My slippers weren't worth taking either. I packed only my razor and toothbrush. The towel and bedding were part of the hostel inventory. My flute was already in my trouser pocket and I had sold my coat last April. I had never owned a hat. I was as ready as I could ever be.

But … where were my documents?

I remembered they were being held at the central office responsible for refugees, and since they were in the process of moving premises as well, my papers had been deposited safely. In case we were interned, they promised they would send the documents straight to the Lagerkommando. My mother can't write to me now the war has broken out so she won't mind if I don't have an address for the time being.

‘Adieu, Mansarde,’ I called. ‘Goodbye to all you mice! You’ll miss me when you look for cheese rinds under the bed.’ At dinner I liked to save a piece of cheese to eat in bed at night. I went back downstairs and deposited the Charlotte Corday in one of the baskets the maid was now filling with books. There was little hope that these items would arrive in one piece, as there were light bulbs at the bottom and books on top. But what can you expect from a chambermaid who won't even speak to you in her native tongue?

If I hadn't walked the route to King's Cross so often in daylight, I would have been lost. The darkness was merciless. It was a blackout because of the war. From time to time, when I could see nothing at all, I stood still and waited. When cars passed and shed their lights on the streets for a few seconds I got up and moved a few metres further on. I had no real plans of where to go. Five pennies was all I had. If only I owned luggage or better clothes I could have stayed in a boarding house and lived on credit until my next payment. But from the way I looked, I could expect no courtesy. My only item of respectable clothing was the immaculately kept gas mask with a brand-new white hemp cord; but everyone knew that these were free, not for sale and compulsory to carry around. I had a few telephone numbers of fellow emigrants who lived in posh hotels but I wasn't brave enough to invest my few pennies in the risky venture of a phone call. And how would they treat me in reception? My heels were worn and my tie was pieced together from bits of one of the ladies’ old dressing gowns.

It had been some time since the last car had passed me to cast a faint light on my path. I should have spent less time thinking and more time paying attention. Now I was truly lost. I could hear cars passing in the distance but I must have landed in a side street with no traffic. I rationalised – I may be lost but even if it seems like I'm in the midst of a deserted mine, I am in a million-strong city. Within a few metres of here there must be people in their dressing gowns and slippers, playing with their offspring, making toast and reading the Evening Standard. If it weren't for the blackout curtains I could make them out, I was sure of it. Someone had to come by and help me out sooner or later. I felt around for something solid and sat down. Something crashed to the ground. I must have knocked over an empty milk bottle in the darkness. It shattered but luckily I was unaffected as there was no dampness and the stones remained dry and warm. As I was seated comfortably I thought that I might as well continue my train of thought …

I came from a country that used to be free and happy. We spoke German at home, that much was true, but was that reason enough for Herr Hitler to come along and take over? I was almost always a good boy and often stayed at home to help my mother, although she did send me to the mountains to live with her brother for a while to build up my strength because I was a weak child. I wondered why my mother, teacher and priest all tried to convince me to be a good and honest young man and put up with no injustice from others? When this was put to the test and I followed these directives, it caused only shock and dismay. The first time this happened was when I was buying a new exercise book. This was immediately after the invasion of the German troops and in the midst of jubilation. The window display of the stationers with the funny name was almost empty. Only the owner, an old man with a grey beard, sat there with a sign around his neck – Saujud, swine of a Jew. It was written with no orthographic errors unlike the other signs in similar shops, and this was rare. An SA man guarded the shop. It was already obvious to me that no one would be able to buy an exercise book in the foreseeable future. I didn't walk on. It was a disgrace to humanity; and I felt sorry for the man in the window display with the sign around his neck. He had always been so kind to me and friendly. Perhaps I could help.

‘Why don't you let me sit in the window in his place?’ I asked the SA man. A few people who had been eyeing the display came a little closer so that they could follow what was happening. ‘Just think,’ I continued, loud enough for the others to hear, ‘how embarrassing it must be for the old man. Imagine if it was your father.’

One of the women said, ‘Really, what is the point? Why should an old Jew sit in the window like that?’ The other women murmured their approval. At this time and location it wasn't unusual for the crowd to change their opinion. It resulted in the SA officer setting the old man free. People weren't really that bad; they were easily led astray. One only has to lead them on the right path again. With these comforting thoughts in my mind I fell asleep.

The next attempt was less successful. Two days later, quite early in the morning, I passed a group of elderly women who were being led away by the SA for cleaning duties. I think they were mainly wives of old officers and aristocrats, loyal to the emperor. They were carrying heavy buckets filled to the brim with lye, brushes, brooms and cleaning rags. A particularly unsavoury rabble who had recently converted to the new regime followed them, scoffing and jeering loudly. One old lady with snow-white hair stopped to rest. She could go no further with the amount she was carrying. I stepped in, took her bucket and said: ‘Gnaedige Frau’ (‘Madam, let me carry that for you’). I was not sure why they felt they had to beat me to a pulp for this act of politeness. If I had not pretended to be dead, they would have carried on relentlessly. My poor mother hardly recognised me. I had to stay at home for a few days so my wounds could heal.

I was disappointed – I had no chance! How could I change the mind of 80 million people? I had to change my methods. I would either need several hundred kind helpers or I would have to speak to larger groups of people at one time. It would not be easy recruiting helpers, so I chose the alternative – to speak to the masses. Sadly, this was not as easy as I had imagined. The masses that gathered to hear the speech of a bigwig might have listened to what I had to say. The speech they had come to hear was to be about the extermination of the inner enemy. I got no further than ‘In the name of humanity’ before the Gestapo grabbed me by the collar of my overcoat. I managed to free myself by slipping out of the coat and darting between their legs. I then was able to get through to the next street by running into a house with two exits, and then jumped onto a tram.

I remembered my coat pocket held the deposit receipt for my faltboot, my collapsible boat. Here I had left a copy of a book from the library. The author was a Jewish philosopher and it was about the freedom of speech. There was a register showing who the current holder of the copy was. If the Gestapo followed this lead, they would track me down within a few hours. When I got home, I told my friends and family. Everyone was shocked. My friends all contributed money to enable me to cross the border straight away. Once out of the country I was passed from pillar to post until I finally ended up here in England.

A car finally approached. It was heavy and moving very slowly. I got up and ran towards it, waving my arms in the headlights. I hoped this car would give me a lift, at least to somewhere I had a chance of finding my way from. It stopped. It was a Rolls Royce with a slightly unusual shape. The bonnet was exceptionally wide and the roof was very high. The driver and his partner were wearing top hats and there was a large black box behind them – it was a hearse. I decided against the lift. ‘Sorry,’ I called out and stepped back on to the pavement. The car with the sombre profession appeared to have gotten lost in the blackout; the headlights were aimed towards the houses and walls, on the lookout for a clue to their current position – a street sign perhaps or something else. This proved to be fortuitous for me because the gloomy memory of the hearse was soon replaced by something far more pleasant. A larger-than-life image of a beautiful girl with long flowing hair and rosy cheeks was glowing in the darkness. Her white neck was shimmering and her shapely arms were beckoning me. For a few seconds I thought I was witnessing a miracle, but then I understood. The headlights were directed at a large poster and had singled out this perfectly sharp image. I could not make out what her sweet smile was extolling: soap, toothpaste or shampoo? Something to eat or strengthen the nerves or perhaps washing powder? The fair image disappeared. The searchlights found a clue to our whereabouts. We were only a few hundred metres away from Upper Regent Street.

As I walked on I asked myself: why was I not only without a home country but also without a home and poorer than I had ever been? Was I being penalised for the fact that I had spent recent months following my personal interests and only worrying about satisfying my creature comforts? Should I travel back to the Reich and continue with the fruitless task of trying to persuade 80 million people to change their opinion as one single soul labouring against the masses? That was the error. What a ridiculous mistake to think that I could influence millions of people when their individual opinion counted for nothing. In the whole of the Reich there was only one man whose opinion counted – and that was Hitler himself. I should have tried to persuade him instead so that he would see the error of his ways and end this war that was both wrong and unjust. This insight came a little late as I was now in England and there was no opportunity for me to get back to Germany and penetrate the Führer's inner circle. Disillusioned and a little bitter, I told myself: just give up! There is no point in fantasising. You need to think about yourself and the future. And right now you need a bed for the night!

I decided to head for the West End. This is where I would normally find my friends and acquaintances. There was a good chance I would bump into one of them, start talking and then be invited to stay the night. I did not think I would even have to beg or complain about my situation too much. It was generally enough to look a little sad and despairing. The darkness made things difficult. If only I had a big illuminated sign or something to hang around my neck, but even then no one would be able to see what kind of face I was pulling.

People of various shapes and sizes were running into me, as I had been standing still for a few moments. I could sense by their prods that this was no ordinary flow. People were heading in more than one direction. An entrance covered with a heavy black curtain became clear to me. On it red neon letters proclaimed: OPEN ALL NIGHT, MUSIC.

Thank God for that! Music was allowed again.

People pushed in and out as the flow led me towards the entrance and I found myself heading inside. It must have been fate. I didn't suppose I could invest my 5d in a profit-making way so I thought I might as well spend it. Why wait until I got even hungrier and more tired? Judging by the raincoats, packages and dialects my neighbours in the human stream called their own, this was more a haven for the common people, not the upper classes. I would rather avoid being somewhere where custom would dictate that I tip half a crown in the absence of having the right change to hand.

Despite my resolution not to be impressed, and although I had been here before, I took in the lavish luxury of the establishment. Marble, cut-glass mirrors, concealed lighting illuminating the vaulted ceiling, porters in uniform … Had the flow of people not carried me, I might have turned around and ended up in a cheap pub eating fish and chips or sausages and cabbage instead. The stream carried me past the reception desk. I reached into my pocket and counted the coins by feeling with my fingers. They were all still there. At the other end of the hall there was a podium with white-suited musicians, instruments at the ready. The conductor was just raising the bow of the violin as I tiptoed past as quiet as I could. I had just taken my seat when the dulcet tones began. If only the other customers had been as considerate. They spoke in loud voices, rattled their cutlery and plates, shouting their orders loudly to the waiters. I, for my part, had no wish but to remain invisible for the time being and surrender fully to the rhythm of the melodies.

The band was playing the Intermezzo from Cavalleria, a piece of music that in the best of times could move me to tears. It was either that or take out my flute and play along; both options sadly out of the question. People were still coming and going, getting awkwardly in and out of their coats. A new experience for me: the aim of many was not to listen to music, talk to friends, or eat and drink, but rather to find the most complicated way of shedding their parcels, gas masks, umbrellas, hats and coats. How complicated life was for the well-heeled! I was much better off, I thought. I had nothing to stash away under seats and behind tables. Full of enthusiasm I listened to the music, determined to reach the most paradisiacal state of bliss that my 5d would buy, regardless of what the waiters thought of me. And who knows, I thought; they might even play La Bohème or Butterfly.

It was not possible to remain invisible. The waiters were already attempting to take my order, approaching me from all possible sides. Finally I had to acknowledge their presence. I took the menu as if I had never looked at it before. It was a smallish leather-bound booklet with multicoloured print. I explained to him that I needed more time. My English was improving. He seemed to understand and left me in peace to make my choice.

There were two pennies on the table which I could have swiped without anyone noticing. My assets would have increased to 7d; enough for a proper meal of bread and butter, for example, with two sardines or bangers and mash or even soup and an egg. However, 5d did not yield quite as much. I could not bring myself to order a mere cup of tea when water would do just as well to quench my thirst. The waiter returned. I pointed to the 2d, for I was and wanted to remain, an honest man. He seemed to misunderstand and disappeared, reappearing with a fresh tablecloth. A few practised movements and the old tablecloth, by no means pristine, was gone and replaced by a new one. He then removed the 2d from under my eyes. I could hear the rattling in his pockets and the coins were gone. It was time for me to order. It was a good thing my hearing was what it was. ‘Chicken liver is out,’ I heard another waiter say. Perhaps my waiter had not been into the kitchen for a while. I ordered the liver; he noted it and went off. Another fifteen minutes of paradise passed. The band still did not play La Bohème or Butterfly but We’re Going to Hang out the Washing on the Siegfried Line, not a piece I particularly enjoyed but I tried to memorise it because I thought it might work well on the flute. I tried with little success to ignore two gentlemen and a lady behind me who were speaking loudly and unabashedly in German. But they were beginning to interest me. To turn around and stare at them would have been impolite and was unnecessary. I could observe their table in one of the many mirrors if I looked straight ahead. Admittedly, I could only see them the wrong way around. There was a young man with broad shoulders and a smart haircut, a greying older gentleman and a younger lady with platinum-blonde hair. They must have had a few drinks before they came in because they were definitely in ‘high spirits’, but here they were only drinking coffee. Finally the band finished We’re Going to Hang out the Washing and was silent. I could now hear every word they were saying and paid full attention.

‘How much have we earned all in?’ asked a bass voice, probably the greying man.

‘I haven't counted it,’ replied the metallic tenor voice, undoubtedly belonging to the young man with the mass of hair. ‘Here,’ he was beating his breast pocket. ‘You can hear the rustling noise. Loads of £10 notes. And the timing was perfect! If the war had broken out twenty-four hours later I would have lost it all to the Portuguese agent who disappeared to South America. Poor German bigwig in Berlin! I can see him now, tears rolling down his fat cheeks. But I don't dare let the money out of the country. Rather than risk coming into conflict with the Defence Finance Regulations I'd prefer to waste it and drink on my own. I mean with you guys, ha ha!’ He was sounding merrier by the minute.

‘Leo,’ said the man with the deeper voice. ‘I hardly recognise you, pull yourself together. Yes, it is an achievement to receive a handsome sum in English currency as a result of the outbreak of war, and I have no sympathy with the German bigwig. But that's no reason to lose control of yourself like this!’

‘Oh, you and your self-control, Herr Doktor,’ the girl squealed. She probably hadn't had the most to drink but seemed to tolerate the least. She also had a rather off-putting speech impediment. ‘Come on, Leo,’ she lisped. ‘Celebrate (th-elebrate) with me. I'm a bird, flying high in the sky (thky), high as a kite. Tweet, tweet!’

In the mirror I could see she was getting up and trying to use the seat as a step onto the table. People began to stare.

‘Sit down, Angelica!’ the tenor hissed, ‘or I’ll feed you to the dogs.’ She put up some resistance but fell back into her seat, throwing her things to the floor in the process. Her hat, handbag and umbrella rolled towards my feet. I could no longer ignore the situation and turned towards them. The music was changing: Troubadour, Schon naht die Todesstunde (The Hour of our Death is Approaching). Not quite appropriate but I had no time to enjoy the melody. I could only make out the skinny back of the girl in her ill-fitting suit. She was crawling on the floor, looking for her treasures.

By now I was looking right at the man with the tenor voice; he had a pleasing, well-balanced and well-fed face with a strong chin. Sparkling blue eyes were staring back at me. His complexion was like milk and blood, a dimple in his cheek, his smooth forehead set off by the wellcoiffed light brown curls. He left me no time to admire him further. He grabbed the lapel of my jacket. I was none too pleased about his rough treatment. He pulled me up, shouting: ‘You old crook! Have you finally escaped? You see – you managed it without my help. But I'm pleased. I'm really pleased!’

How could I escape this sudden outburst of unwanted attention?

I responded coolly: ‘Sir, I am neither old, nor a crook, escaped or otherwise. Besides, I don't even know you. Please be so kind as to let go of my jacket.’

His reaction was one of unfeigned surprise. Despite being the victim of a misunderstanding, I was playing a manly and dignified role. The waiter had returned and was standing behind me: ‘Chicken liver is out, sir.’

The girl by the name of Angelica had packed her things and was ready to leave. ‘You know what he's like, full of fun and jokes!’ Once again she demonstrated her speech impediment. I looked at the girl more closely. There wasn't much of her. Without the make-up, the platinum-blonde hair, false eyelashes and the speech defect, she was very ordinary – and this girl was called Angelica!