7,40 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Artifacts of Lanedon

- Sprache: Englisch

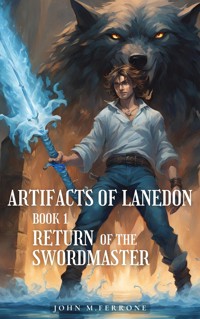

In a world called Lanedon, five Artifacts enabled the High Council to keep the evil Lord Maligor at bay for centuries. But Maligor is cunning, and he has used powerful sorcery to open a portal to a parallel world where he has hidden the sword Aurcrin—the greatest of the Artifacts—so it can never again be used against him. This other world is a place called Earth.

Krem Connelly just graduated from a college preparatory school in the Chicago area. His life has been a lot like his name: odd and obscure. But unbeknownst to Krem he happens to be a bloodline descendant of a special family in a parallel world. While backpacking in France he finds a sword that was never meant to be discovered. When he grabs it, it opens a portal to a place called Lanedon.

Upon stepping through he begins a journey to pursue a destiny that he does not understand, that only he can fulfill, and that will determine the fate of Lanedon. He must find the other bloodline descendants and help them acquire their Artifacts if they are to defeat Maligor. He must also discover his true self and come to terms with the history he has lived on Earth, and the history he has inherited in Lanedon.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 731

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Artifacts of Lanedon: Return of the Swordmaster

By John M. Ferrone

Copyright©2024

ISBN: 979-8-9910864-0-0

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: The Teen Who Could Meditate

Chapter 2: The Farmer and the Apparition

Chapter 3: The Flight of the Spy

Chapter 4: Somepin’ Special

Chapter 5: A Stranger in the Ruins

Chapter 6: The Wolf-Lord and the Gestaban

Chapter 7: The Secret Passage

Chapter 8: The Cave of the Flaming Sword

Chapter 9: A Fort in the Woods

Chapter 10: The Last Fire Mage

Chapter 11: The Bond and the Portal

Chapter 12: Confiding in the Pastor

Chapter 13: The Tornado

Chapter 14: The Awakening of the Fire Mage

Chapter 15: The Goblin Arrow

Chapter 16: The Struggle for Command

Chapter 17: The Pipe Code

Chapter 18: A Stranger in the Pastor’s Home

Chapter 19: The Path to the Village

Chapter 20: The Winged Wolves

Chapter 21: Bled Island

Chapter 22: The Siege of Tellanac

Chapter 23: The Hike to Tellanac

Chapter 24: Assault of the Shadow Stalkers

Chapter 25: The Swordmaster Revealed

Chapter 26: A Father’s Last Plea

Chapter 27: The Interrogation of Grolin

Chapter 28: The Path to the Seer

Chapter 29: The Decision

Chapter 30: The Legend Keepers

Chapter 31: The Canyon of the Seer

Chapter 32: Images and Questions

Chapter 33: A New Beginning

Chapter 34: Shadows in the Ruins

Chapter 1: The Teen Who Could Meditate

The glow from the fire of the burning goblin bodies was fading the further they marched away from it and was soon no longer visible amidst the thick fog. The dwarves and Krem made their way along the edge of the woods, following a level path that skirted the hillside just above the tree line. The dwarves were silent and steady, and Krem tried his best to avoid making noise, as well as to keep up. They were battle-weary and some were assisting their wounded brothers, but the dwarves moved at a surprisingly quick and steady rate. The occasional head-turn from one of his bearded companions let Krem know that he was not impressing them much with his stealth.

The fog made it difficult to see ahead, and when the path suddenly turned to the left and sprang into the forest between two trees that formed a low arch with their branches, it caught Krem by surprise and he wanted to hesitate—but he didn’t for fear of being left behind by the quickly marching dwarves. And if the night and fog seemed dark, the forest, now, was an expanse of blackness that made Krem feel like he had walked through a veil and somehow stepped into black velvet. He began stumbling on roots and after falling forward into the dwarf just ahead of him, he decided enough was enough and drew his sword from his side and whispered “Lichtene”; the sleek blade began to emit a soft blue glow that allowed Krem to see the path a few feet in front of him.

The dwarves moved at a steady pace that made Krem hurry every few steps to keep up. He tried taking longer strides but that made him fall behind faster; when it came down to it, he just had to quicken his steps. Although he had never really been pushed to his physical limits, he knew he possessed an uncannily high level of endurance that emanated from a hidden recess deep within him, an intrinsic quality that often surprised him. He had learned to draw strength from it through meditation, and as he hurried along with the dwarves, he searched for that resource deep within him.

But the marching continued, and the shock of the entire situation was taking a mental toll on him. Regardless of his strong endurance, Krem was out of shape and he knew it. He never was much of a sports jock in school, although he was very athletic—he had a strong and wiry physique, excellent coordination, and an intuitive feel for his body’s capabilities. He just hadn’t play sports much.

It wasn’t for lack of interest that he avoided organized sports. In fact, he often tried to fit in on the playground or in less formal sports situations, like pick-up basketball. He marveled at what some of the other kids could do with a basketball.

As he hurried along with the dwarves, his mind wandered back to a playground memory when he was fourteen.

“We’ve got Crap, so we get the ball first,” Curt said. He held his hand out, palm up, his gaze on Bruce who stood facing him, sizing up the teams. “C’mon, Brucey. You know it’s fair. Gimme the ball.”

Bruce shook the shaggy brown bangs out of his eyes, glanced over at Krem, the kid they called ‘Crap’, and then back at Curt, “Yeah, alright.” He let the basketball drop and bounce towards Curt and then turned towards the rest of his team and called them in to talk about who they were going to guard.

Curt grabbed the ball and turned to do the same with his guys. Krem was still trying to pull his sweatpants down and over his shoes; both feet were stuck and soon he was sitting on the blacktop and taking his shoes off to free himself. He looked at Curt and the other guys who were all staring back at him, hands on their hips.

Garrett looked sideways to Curt, then back at Krem who was finally putting his shoes back on, and then asked, “Who’s he gonna cover?”

“Billy’s not that quick, and he’s not tall, so Krem can stick on him. Should make it a four on four game,” replied Curt.

Krem stood up, tossed his sweat pants over to the side, and then jogged towards the guys. They broke their huddle and Curt starting dribbling the ball as they advanced up the court to Bruce’s team. “Krem, you’ve got Billy when we’re on D.”

As Curt brought the ball up the court, the other guys fanned out and began moving around the key, setting picks, passing the ball, and pushing for position. Krem bounced awkwardly on the balls of his feet, hands up in case the ball happened to come his way. But he didn’t really expect it to. Billy guarded him, and the two occupied a space to the right of the top of the key, the game mostly occurring around them. Anyone watching could tell that Krem was simply the guy added to make the teams even. He knew it, too, but it didn’t bother him. He was glad to be on the court with the guys, even if he never would touch the ball. There was something about belonging that was important to Krem—not important in the same way as it is to most kids—important because Krem was, at the awkward age of fourteen, very certain that he did not, in any way, shape, or form, feel like he belonged. Sure, he looked like any other gangly fourteen-year-old with budding masculinity and a slew of pimples, yet this certainty about not fitting or belonging was not immature. Rather, it was rooted in a wisdom that—something else he was very certain of—was atypical of kids his age, and, in fact, atypical of most adults.

This wisdom—or something he told himself was simply an advanced awareness of things—he attributed to his ability to meditate. He was quite cognizant of this uncommon awareness (let alone the ability to meditate as a teenager), and it had often served him well. But it also left him quite out of touch with the moment, for his mind would wander towards the focus of his meditation—something surreal, and very out of the ordinary. Any person who meditates knows that focusing your mind on one thing, perhaps even just a sound, or a number, or a rhythm is difficult enough. For Krem, though, the focus of his meditative efforts had always been the image of a magnificent sword—and not just any sword, and not just a simple image of a sword. The sword in his mind had a jewel-encrusted hilt, and its blade was engulfed with swirling blue flames, and it was suspended over an ornately carved stone pedestal, somewhere inside a small cave with wet, glistening walls that twinkled in the light of the blue flames. This image that had come to Krem’s mind at first when he turned seven, had become the object of his concentration, and it was as easy for him to conjure it in his mind as it is for any person to think of a stop sign.

The basketball bounced off Krem’s head and into Billy’s hands, and Billy quickly passed it up the court to a streaking Bruce who took it in for an easy breakaway layup.

“Krem! C’mon, man!” Curt shouted.

Krem, his head still ringing from the shock of the basketball, looked over at Curt who scowled at him while walking down the court to retrieve the ball that Bruce left behind.

“Yeah, Krem, c’mon. We need ya’,” Garrett offered quietly as he jogged past Krem to catch up to Curt.

Playing defense was a lot easier for Krem to engage in, because it was a good test of his intuition. Billy never touched the ball, except for when it bounced off Krem. Krem had a gift for knowing what the other players were going to do well in advance of when they did it, and he was able to be in the right place at the right time to prevent Billy from receiving a pass or pulling down a rebound. One would think that with this gift of insight that Krem would excel and be a key player on his team, but his lack of self-confidence kept him from sharing or acting on his insights, except to help him in his own task of guarding Billy. It’s funny how things like that work with teenagers—how something that is such a gift and a strength can actually lead to an insecurity and trepidation. Perhaps it’s an awkward imbalance between humility and confidence, an imbalance that teenagers struggle with, often without knowing they are struggling.

In the end, it was Krem’s hand that deflected a pass that was not intended for Billy but that came close enough that Krem could reach out and swat it to Garrett, who passed up the court to Curt who took it in for a game-winning layup. Curt had given Krem a nod of approval, but no words accompanied the gesture. Garrett had smiled and high-fived everyone, including Krem. And there was a lot of chatter about certain plays, and bragging about clutch moments, and finally the guys dispersed and headed off in two’s and three’s, as Krem sat on the bench trying to put on his sweatpants over his shoes. There was something satisfying about having played and having contributed, but he still didn’t feel like he belonged. Most kids wouldn’t dwell on this feeling; in fact, most wouldn’t even be conscious of it—they would just experience it and react to it, and let it shape their feelings and actions. Krem analyzed it, though. He possessed wisdom beyond his age, and an awareness of himself and of what was going on in his head. And what he realized was that this particular lack of belonging was itself not the issue and it didn’t cause him any hurt—it was, instead, his belief that he couldn’t belong, not now, not ever. It wasn’t a matter of figuring out how to belong. There was something different about him, about his essence, about his being, about him, about him in his totality that would prevent him from ever really belonging among his peers. And he knew this about himself.

“So where do I belong?” Krem muttered out loud to himself as he knotted the first of his shoes which he eventually had to take off again to put on his sweats.

“What?” came a voice down the bench to his left.

Krem jerked his head in surprise and there was Garrett.

“Sorry, I thought everyone had gone,” Krem offered in a lowly voice.

“You know, Krem, for as much as you can’t play ball out here, you have somethin’ goin’ on that’s kinda cool. Can’t put my finger on it, though.”

“Me either,” laughed Krem, and he smiled at himself, now tying the right shoe.

Garrett finished stuffing his things into his bag, except his ball. He clutched a towel and he dragged it over his neck and through his short, black hair and over his face one more time. He slung the towel over his shoulder, grabbed his bag, and then tucked his ball under his arm. He was just a tad shorter than Krem, but even at fourteen he was far more muscular and cut—he also played football and as a linebacker was a menace to running backs. His thick, dark eyebrows and dark eyes, underlined with eye-black stripes looked intimidating through a face mask, and the beginning of stubble on his face made him look a lot older than he was. He was just one of those kids who happened to go through puberty much sooner than most his age. But for all his tough guy look, he usually had a kind expression that fit his small nose, and above all, his dark eyes shined with intelligence and curiosity.

Garrett walked towards Krem, and as he passed by he slowed down and came to a stop just long enough to offer, “This is gonna sound weird, but when you deflected that pass to me, for a moment I thought that you knew it was gonna be there, and it was like slow motion watchin’ you decide to flick it out of the air right to me.”

Krem didn’t look up at him. He fumbled extra-long with the second knot, the back of his neck tingling and growing hot with anticipation and a sense of fear, a fear that maybe Garrett could see into him and know what he had been thinking. How would he explain any of it? His detachment, or the blue-flamed sword, or any of it?

The basketball slapped hard against the blacktop near his face, and Krem jerked upward in surprise. Garrett clutched his ball again and grinned down at him. “Did you hear anything I just said?”

“Yeah,” said Krem.

“Well?”

“Well what? It was nothin’. Just stuck my hand out and got lucky. Hawkish peripheral vision, I guess.” Krem smiled at his own attempt at wit.

“I don’t buy it,” Garrett said. “I know basketball—I know the plays, the moves, everything. And you don’t. And yet every time on defense you were always in the right place at the right time. You interrupted at least eight of their plays. I started keeping count.”

“Hmm. All I did was guard Billy,” Krem offered. He was now feeling pressed and he absolutely did not want Garrett learning too much about something he himself didn’t know enough about.

“Listen, Krem. You know your nickname is ‘Crap’.”

Krem sat up and looked directly at Garrett. He knew that that was what they called him when it came to choosing up sides. It sort of amused him, though, to hear the captains negotiate who would take Crap. And then he said, “You’re saying that because…?”

“It doesn’t bother you! I mean… why not? You show up all the time and we use you—just to make teams even. Any other kid wouldn’t come back.”

Krem didn’t respond. He knew where Garrett was going with this, even though Garrett was still trying to figure out what it was that was bothering him.

“I’m not picking on you, Krem. You’re sorta cool in an odd way. It’s kinda like you’re… you’re…” Garrett paused; he didn’t know how to finish the thought.

“Beyond all of you?” Krem finished it for him. It was a bold statement, but Krem decided it was time to explore himself a bit more, and test himself among his friends.

A blank look occupied Garrett’s face. Krem stood, now, a bit taller than Garrett. He looked down into Garrett’s expression, holding his gaze intentionally, and he could feel a power emanating from him and for the first time since he had become aware of it a few years back, he decided to use it to grip Garrett’s presence.

Garrett wanted to back up a step, not out of fear, but instinctively because he could feel something about Krem that needed more space. But he couldn’t move. He stammered, “Yeah, somethin’ like that. Beyond us.” He paused a moment. Krem didn’t interrupt, and Garrett said more, “Not the word I woulda used. But, yeah, beyond us is right. And… I guess I wanna know more.”

Krem smiled and released Garrett from the mental grip. Garrett stepped back with fear in his eyes, now, because he was suddenly aware that he had been held, held by Krem in some way.

“Garrett, do you ever have the same dream, over and over and over?”

Again there was a long pause between them, and then Garrett said, “No.”

Some different kids, younger kids, were coming onto the playground and towards the basketball court. Krem looked over, but Garrett did not take his gaze from Krem.

“See that kid there? The one with the black shorts and shoes? He’s what, maybe thirteen?”

Garrett finally looked over, “Yeah, that’s Joel Kramer. He’s thirteen. Why?”

“He’s got a mean heart. Not his fault, but it’s who he is.”

“What the heck?” Garrett was shocked. “You don’t even know the kid, and what does that mean, anyway?”

“It means that he’ll hurt people his whole life, and it will get worse and worse.”

Garrett tried to laugh off the comment. He was struggling between being taken aback by Krem and being fascinated at learning more about what he had been perceiving about him. “That’s a bunch of BS. What are you, some sort of fortune teller?”

“No. I’m just beyond you. I can’t explain how, because I don’t know. All I can say is that I’ve had the same dream about this thing—the same dream since I turned seven, and the more I think about it and focus my mind and energy on it, the more I go beyond you, and I know things. I just… know things.”

Garrett’s expression soured at the thought of being put down, of being inferior. Krem noticed right away and offered, “Listen, I don’t say that to cut you down. Maybe ‘beyond’ is the wrong word. Maybe ‘different’ is a better word. You’re so much better than me at so many things, and there are a few things that I’m really good at because, well, because I guess I’ve honed my mind by meditating so much on this thing in my dreams.”

Krem was like a man talking to a child, it seemed. He knew that the word ‘different’ didn’t come close to characterizing the gap between himself and Garrett, and everyone else for that matter. The word ‘beyond’ was, indeed, accurate.

“I’m not sure I know exactly what you just said, but I think I get it. And I know I feel something. That sounds crazy, doesn’t it? Have you ever had someone tell you that they felt somethin’ coming from you, some kind of vibe, or something?”

“You’re the first, Garrett. And that, by itself, says something special about you, too.” Krem concentrated on sending a nourishing energy through his gaze to Garrett.

Garrett’s chest swelled and he could feel the warmth of validation flooding through him. He blushed a bit, yet in the end he was completely unaware of the invisible touch from Krem.

For the moment, Krem’s presence was powerful, and it was outside and beholden to anyone near him, but only Garrett was there. It was Krem’s first venture in exploring himself and what he smartly sensed was a gift, or a talent, perhaps even a power that he possessed. He reached out and chucked Garrett on the shoulder. “C’mon. Let’s get goin’.”

Garrett smiled and they turned away from the court and headed off towards the street. From behind them they heard the shouts of the kids on the court, and turning just in time they saw the Kramer kid slug another smaller boy in the stomach and then push him over. It wasn’t a fight that needed breaking up—just a moment of posturing. Garrett looked at Krem. Then they turned again and continued walking out to the street.

It had been a good test, and Krem was pleased at the results, as well as the mere fact that he was able to seize the opportunity when it presented itself to explore some of his gifts.

“What’s the thing you keep dreamin’ about?” Garrett asked.

“A sword.”

“A sword? You mean like Excalibur? Or like in Dungeons & Dragons… that kind of thing?” There was great curiosity in Garrett’s voice.

“Kinda. I’m not sure. It’s just there, in my dream, waiting for me to find it,” Krem stated matter-of-factly.

Garrett couldn’t mask his shock, “You mean you think it’s real? But it’s just a dream, isn’t it?”

“No. I’m pretty sure it’s real. And,” he looked sideways at Garrett with a reassuring smile, “I’m also pretty sure that I need to find it. And, Garrett, you must promise me that you will never mention this to anyone, ever.” He stopped and looked at Garrett squarely, placing a hand on his shoulder.

“I promise,” said Garrett.

He had followed the dwarves for nearly four hours, winding through the forest, constantly on a downward slope. Thank goodness for the downward slope, as Krem would not have made it up a hill, at least not at a dwarven pace. Their path cut through an occasional glade, and at the lower altitude the fog had dispersed and Krem was able to see stars—and wow were there stars! The starlight in the glade was nearly as bright as the light from the sword, and the stars were one more reminder that he was some place very different, not that he needed any other reminders given that he was marching through the woods with a band of dwarves, having just slain dozens of goblins with the sword that he was now using to light the path at his feet. In the sky there was no Big Dipper, no North Star. Instead the sky was full of points of light, some blue, some white, and many with shades of pale green, their varying colors creating a distant carnival light effect, similar to what he imagined the Northern Lights to be, although he had never seen them. But the colors were not moving like the Northern Lights. This sky was a fixed black canopy with ten times as many stars as he had ever seen, even when he spent the night at his grandfather’s farm and sat out by the fire pit with him late into the night listening to the breeze rustle the tassles on the corn.

Krem’s mind was wandering again, this time with questions. Was the sun he had known his whole life one of the stars above? Was it really possible that he had left one physical world and entered another through a portal? A portal?Really? That was the stuff of science fiction and Hollywood! Sure, he was a fan of the Harry Potter series, and of course The Lord of the Rings, but what sane person would ever consider entering a world like those, a possibility? Perhaps that was the point: was Krem suffering from a mental illness? He didn’t think so. And this was not a dream, either—at least he was convinced it was not, because the only dream he had ever had, or remembered anyway, was about the sword. This was real, as real as it ever gets, as real as the smell of the pine trees whose bows they now tread silently beneath after having left the glade, stepping softly upon a thick bed of damp pine needles. And despite the preposterousness of it all, Krem felt quite at peace, and actually quite at home.

In the end, when he searched deeply within himself for a genuine reaction to what had transpired since the mysterious encounter in the courtyard of the ruined castle, what he felt was a sense of coming home, as if this was meant to be. He was meant to find the sword, and therefore, he was meant to be here, now, following the dwarves through the forest, unaware of his destiny but somehow sure that he had one. And isn’t this what he had felt his whole life thus far in his short eighteen years? That somehow he had a destiny to fulfill? What teen doesn’t think that they have a destiny, though? But on the other hand, Krem wondered, what teen dreams about a sword each night for eleven years, and then learns through meditation to draw real power from it, and then eventually finds it? There are a lot of kids that Krem could think of who would be having a break down right now… who would have never ventured up the stairs, or entered the battle with the dwarves… who would have never followed along when the dwarves headed away from the scene of the battle in search of a trading post down the mountain. It never crossed his mind, though, as to whether or not he should have done any of these things; each action fit, and felt right.

“I am just different and this was meant to be,” Krem said to himself contentedly, “And that is all there is to it. And I’m okay with that… as long as I someday understand how and why, and why they call me the Swordmaster.”

A nearby dwarf shushed him, and then offered in a gruff voice, “You are different, and you are a gift, and just as you have a destiny, it is now mine to help you be who you are destined to be, by life or death.” At that moment the group traversed through another starlit glade and Krem recognized that the dwarf who had spoken to him was Brentor, the one he had healed from a mortal wound after the battle above the tree line.

For the first time in his life, Krem felt the gush of genuine belonging sweep over him and he nearly burst out sobbing, or laughing, he wasn’t sure which, and with a bound he caught up to Brentor, slapped his shoulder heartily and walked side by side with him, the dwarf looking up at the gangly teen and beaming.

They continued to walk, their pace having slowed a bit, and in the aftermath of the warm glow of belonging and camaraderie, a thought occurred to Krem for the first time since he passed through the portal: What about his mom and dad? He wondered what they would think when they learned he had simply vanished while trekking through France with a backpack and camping gear. Now THEY would be the ones losing their minds, he figured. What parent wouldn’t? And now a sense of guilt began to edge its way into his thoughts, like a flame from a struck match that takes to the edge of a piece of paper and slowly grows and spreads as it consumes the paper. His first thought was to get word to them. But how? He couldn’t go back—there was something too urgent about following the dwarves to safety. Maybe there was another portal somewhere? Krem’s mind raced through the possibilities, and in the end, he knew that he would have to choose a different time to attempt to contact his parents. And his inner voice calmed him: Remember that the best time to do something is the right time to do something.

He chuckled inwardly at the fact that his conscious mind had very quickly and easily moved past what should have been a difficult moment. His parents would be okay. Yes, they would worry, but they would be okay, and in time he would be in touch with them. Was it maturity, or wisdom, or foolishness that caused this peace of mind? None of those, thought Krem—it was about his destiny, the one he knew now more than ever was real and was unfolding not before him, but with him and through him. He was part of it, and he was shaping it, and what he did not know was the extent to which his destiny would shape the lives of many beings and good people whom he had yet to come to know, but would in due time.

Chapter 2: The Farmer and the Apparition

“It’s a fine evening,” he softly offered, his chin tilted up to see the black sky filled with stars. He tucked his thumbs into the straps of his overalls.

“It’s nice the wind has settled,” his wife replied. “But I’m wore out… I’m headed in. You stayin’ out?”

“Fer awhile,” he replied, turning to her. “Night like tonight… can’t turn my back on it.”

“Don’t be too late,” she whispered, her eyes smiling at him. Then she leaned into him and kissed his cheek and hugged him. “We’re gettin’ old, ya’ know. I don’t want cha’ over-doin’ it.”

“Ah, I ain’t old, and I don’t feel old. Sixty and feelin’ sixteen,” he whispered and smiled, embracing her with long arms. “Good night.”

The screen door creaked as she pulled it open, and again after she moved through the doorway and gently closed it behind. She disappeared into the dark house.

He walked out into the back yard a bit, leaving the fire pit behind him. He stood with his hands on his hips, now hooking his thumbs into the sides of his overalls and surveyed the tops of the trees along the shelter belt, trying to see their silhouette. But the night was dark—no moon in the sky, and no city lights for forty miles: the typically yellow corn was a muddled grey beneath the stars, and the tree-line melted into the black night.

“An unusual dark,” he muttered to himself.

He breathed deep—the heavy, hot summer air almost a chore to gather into his lungs. In the far distance the steady engine of his neighbor’s pivot struggled to break the silence.

“Feels like somethin’s… amiss,” he said to himself again, as if saying it somehow helped him put his thumb on what it was he was beginning to feel in that moment.

An occasional flicker of lightning from a far-off thunderhead lit the horizon off to the west. A bat fluttered by which he keenly discerned by hearing the distinct, quick flapping of its wings. The leaves hung heavily from the limbs of the great sycamore just off to his right—something he could not see, but he knew because it was just so still and quiet. Crickets? Where are the crickets and frogs? They had stopped, but why didn’t he notice until now that they had stopped? That’s when it registered with the farmer that, indeed, something was strange in that moment, as if there were a presence out in the darkest part of the night—where the corn rows ran up to the shelter belt and blackness seems to become a thing of its own.

He held his breath for a moment, trying to hear more distinctly. The far-off pivot motor had ceased. The bat was gone. Now there was nothing.

That’s when a breeze swept down over the shelter belt and into the tops of the corn stalks, stirring them slightly, like a stone that had been dropped into a pond, causing a small wave that would eventually make its way to the shoreline. The corn stalks rustled against each other as the breeze moved quickly across them in the direction of the house and the man standing on the lawn. He couldn’t see the wave coming, but he could hear it. A tingling sensation ran up his back. There were days when he had watched the wind play with the tassels of the corn; it reminded him of watching the surface of the pond on a windy day. Somehow, this breeze felt different—he could sense that there was something strange about it. It seemed too deliberate, if the wind could be such a thing. It was too focused. Too controlled. Nothing but the corn was moving, that he could hear.

The yard fell in a gentle slope away from the house about fifty yards down to the cornfield which extended a couple acres out to the shelter belt. He was halfway between the house and the corn, and the firepit—along with the shotgun that leaned against the chair—were ten yards behind him. The rippling wave across the tops of the corn was approaching quickly and steadily. He felt the urge to turn and run up to the fire pit, but he stood rooted to the ground like a tree awaiting the rushing approach of a thunderstorm.

The rustling grew louder as the line of the wind drew near. It was much stronger than he realized and now a sense of dread pooled in his stomach. But this is just wind, he thought. What if it isn’t? But what, then?

Before his imagination could plug in any possibilities, the breeze rolled up to the end of the corn like a wave approaching a beach and then blew onto the grass and rushed up the incline towards the old farmer who now was more like a dead tree waiting to be blown over.

It knocked him backwards and he fell to his butt, catching himself with his hands behind him. The line of wind rushed passed him to the smoldering fire in the pit and then turned skyward, sending a plume of sparks up into the night.

And then it was gone.

It all happened so suddenly that the old man barely had time to react—yet he still had the presence of mind to listen for the impact of the wind upon the house, perhaps rattling the screen door, or maybe even knocking over a flower pot—surely sending the wind chimes into a frenzied cacophony of noise. But there was none. And hearing none, a tingle again shot up his spine.

He slowly turned his head and gazed back towards the house. A very faint light shown through the curtain of the second story where his wife was making ready for bed, and it cast the faintest of glows about the fire pit area where there he could barely make out the two chairs—and a figure of something sitting in one of the chairs!

The pit of his stomach fell through him into the grass. His mouth went dry. The hair on the back of his neck stood on end as he contemplated this figure, this apparition.

“Who is it? Who’s there?” He croaked, his mouth dry. “Is someone there?” He asked half-heartedly hoping his mind was playing a trick on him, his heart thumping madly in his chest.

No answer came.

He squinted and adjusted his position to look directly up the incline. There was definitely a figure sitting in the chair on the right. It wasn’t a large person, but it was difficult to tell without more light.

He thought about trying to call out to his wife. But the night was humid and the house was buttoned up tightly to preserve the air conditioning—and he knew that even if he tried his voice would betray him and remain cowering in his throat.

“Come forward and sit with me,” the figure said, its voice calm and not unpleasant. “I am not here to hurt you or your wife. I have come to give you important information.”

The voice startled the old man, but it did not make him afraid. Rather, it calmed him. He gathered himself to his hands and knees, stood and began to walk up the incline to the fire pit.

As he drew closer he could see what looked like a man wearing a heavy cloak, like a monk, with the hood pulled over its head. He could not see any part of the person’s skin. Was it a person?

The old man eyed the shotgun. The figure turned its head under its cloak toward the weapon. It stretched out its arm and a whitish-blue hand with burn marks and scars protruded from the sleeve towards the shotgun. The weapon rose into the air and with a wisp of its hand the figure launched the shotgun far out into the cornfield and the darkness.

The old man froze. It was hard to know exactly what had just happened, but he knew that the shotgun was no longer there, and that this figure had made it disappear.

“Come. Sit. If I wanted to hurt you, or kill you, I would have done so already. And you can’t flee—I move as the wind. You might as well enjoy the night with me.” The voice was warm and unexpectedly reassuring.

The old man walked steadily but cautiously up to the other chair. He thought about attacking the stranger, but without knowing who or what it was, and given the mysteriousness of it all, he chose to sit and learn more about what was going on—perhaps there would be a better opportunity to take control once he had had a chance to size up this intruder.

“A little light?” the figure asked, and he reached forward without waiting for an answer, and with that ugly hand he made a scooping gesture in the air in the direction of the fire pit and tossed something imaginary above them—and correspondingly the embers from the smoldering fire were lifted into the air and formed a glowing, twinkling aura all about them. The old man could now see that, indeed, it was the figure of a smallish man wrapped in a monk’s cloak. He could barely see the bottom of the man’s chin, whitish-blue like his hand, beneath the hood.

But the floating red-hot embers!

“How…? What...?” the old man stuttered and gasped.

“Things will happen. And you will remember tonight. And you must write down what you remember. You will think that this has been a dream after I leave. But it is not a dream,” said the cloaked figure in calm, soothing words.

The old man listened. He did not feel threatened. And his mind had stopped searching for answers or explanations. He felt as if he had become one with the chair, much like a person receiving a massage melts into the table. He sat and listened intently. He did not know that he was under a spell.

The figure spoke at length for some time, and when he finished, he simply stated, “I must leave now, but you will see in this chair my mark—and it will be proof that I have been here and that I am real, and all that I have shared with you is the truth. If you fulfill what I have humbly requested of you, you will have saved the people of my world.” The cloaked figure paused, with its head turned directly to the old man who stared back at him. And then it spoke one more time, “Do you accept this task, and can I count on you to fulfill it as I have described?”

The old man, without hesitation, said firmly, “Yes.”

A breeze rolled up the lawn towards the house again and swept the floating embers away. The old man shielded his eyes as the embers circled all about him, and when he was able to look around again, the cloaked figure was no longer there. On the back of the wooden chair was a fresh marking that was both carved and darkened with burns. Upon close examination, the old man discerned it to be an elaborate symbol akin to the capital letter ‘A’.

He sat for a few minutes thinking about all that had been told to him. Then, without any more hesitation he stood, walked to the porch to grab the flashlight he had left on the table, came back to the chairs and picked up the one with the marking and slowly made his way down the slope towards the cornfield.

With great labor, he carried the chair through the corn rows to the other side of the field where the shelter belt rose up like a wall of black ink. Into the line of trees he walked, shining his flashlight and picking his way among the fallen logs and between the new saplings amidst the thick trunks of the older trees until he came to a great oak tree. There, against its trunk he placed the chair, and to his astonishment the tree began to absorb the chair. He turned the flashlight beam on the tree and watched as the chair melded into the trunk so that eventually only the elaborate ‘A’ could be seen.

“Just as he said it would,” the old man said to himself, his lips barely moving.

He then turned and walked back towards the house, stepping on the butt of the shotgun as he went. Picking it up, he again said to himself, “Just as he said I would.”

Stepping out of the corn and onto his lawn, the old man looked up to the window which had now gone dark. The sounds of crickets and frogs came roaring back to his ears, and he noticed how much closer the lightning in the west had come. He could feel the temptation building in him—the temptation to dismiss as a dream all that had happened. He gripped the shotgun tightly and felt the jab of a splinter from the chair he had carried out to the shelter belt.

His mind halted with the jolt of the memory.

“Just as he said I would feel it. One last reminder. God help me. It is mine to do.” And, staring at the dark window, and then down to the door of the back porch towards which he was about to make his way, he muttered one last time—not resignedly, but rather with a sense of determination, “And I will see that it is done.”

Chapter 3: The Flight of the Spy

There is a land lush with greenery and wet with many lakes, rivers, streams and springs among the open valleys, rolling hills, jagged mountains and deep forests. The forests are dense and dark beneath solid canopies; they are expansive, running for miles upon miles to the edge of the ocean and to the base of the mountains. Birds and animals populate the land, and fish are plentiful in the waters. It is a vast land, populated with many creatures and races. The days are long, with a sun rising and nearly setting halfway in its journey across the sky before rising again, to then finally sink beyond the horizon of the ocean. The first half of night is filled with a multitude of stars accompanied by several moons, both near and distant, that give off such a collective illumination that a father could play catch with his son in the front yard beside a quiet street, the popping sound of the ball hitting their mitts echoing among the houses. That is, if there were such a front yard alongside a street. If there were such a father and son. If there were such a game as baseball. But there are no such things in this wild place called Lanedon.

And as the first half of the night is lit, so is the second half inversely black. Black as a cauldron. Black as a bottle of ink into which the tip of a feather quill is dipped and disappears for a moment, completely gone beneath the surface if one were to actually observe it carefully—as if the tip of the quill begins where the ink ends. That impenetrable type of black, such that without a source of light, most things cannot see. In fact, only the dwarves of Lanedon can see in such utter darkness.

The creatures of Greneth, however, thrive in such darkness. If Lanedon is the land of life, Greneth is the land of death. It resides beneath Lanedon, accessible through a handful of rocky crags that open like jagged wounds and that disappear into unknown depths. And it is in these depths that evil creatures wait, always watchful and seeking the right moments to come forth, to take and pervert what is good, to wreak havoc, and to foster slavery and death. And these creatures have a master—the Master of Death, the Lord of Evil, the Giver of Pain, and the one with several other such monikers—Lord Maligor. Feared, reviled, and dreaded, he harnesses the magic inherent in the land and for ages has wielded it via sorcery towards accomplishing his will, which is the absolute destruction of those opposed to his domination. For Maligor, killing and taking life is too easy, too unfruitful. Breaking the will and mind of those who oppose him is his preferred goal. A cunning shape-changer, he is a wizard at his core, compelled by malice yet sheathed in charm, he is what a father and son discussing religion might refer to as the devil.

Deep within Lord Maligor’s underworld of Greneth is a dish-shaped valley filled with water and with a tower at its center that soars three hundred feet above the lake, its pointy spire nearly reaching the craggy bottom of the land of Lanedon that spans all of Greneth—a veritable sky, or ceiling, of rock. A soft, blue glow emanates from the ore in the rock ceiling, illuminating Greneth in a perpetual bath of twilight, against which the spire is silhouetted. Made of smooth marble and reinforced with Maligor’s sorcery, it is slick like a polished rod and stronger than steel or stone. The air surrounding it induces thoughts of hopelessness that would subdue the stoutest of hearts, and wraiths continuously patrol the sky, hidden within the strands of swirling fog that never dissipates. The tower is unassailable, unshakable, and impenetrable, and it is his fortress from where he commands his legions. It is also a laboratory where he channels the ever-present magical energy into evil devices—spells, potions, and weapons, all of which he has tested and perfected during the wars with those who would oppose him in the land above.

At the base of the tower, beneath twenty feet of water, is the only entrance: a stone door—guarded both by magic and the ominous presence of two great pukel-trolls waiting to spring to life with their massive hammers. A single window opens near the top of the spire through which Maligor collects the magnetic energy of the ore, or captures the waves of electricity that pass through Greneth’s sky in conjunction with the passing of the moons during the first half of night in the sky above Lanedon, both of which power his sorcery.

And, once upon a time ages ago, Maligor was nearing completion of his greatest strategic endeavor, one that would once and for all remove all barriers to his domination of Lanedon and its free races. Simultaneously, a figure no larger than a small child was somehow climbing the tower towards the window….

It was an impossible climb. At least, it was supposed to be impossible. Yet Narda clung to the tower’s smooth marble surface with her tree-frog-like fingers and toes, slowly inching her way higher. She looked down to the water—black as the marble of the tower, a hundred fifty feet below—and then up in the direction of the window towards which she was climbing: another hundred and fifty feet higher. Snappy whips of wind desperately tried to peel her from the surface, but she would not be so easily thwarted. She was a Muirling, a rare human-like creature that preferred the rocky cliffs at the ocean’s edge to forests or other landscapes—she was used to the wind, the height, and the water far below. Despite her conditioning for just such a task, this climb was different. The stakes were high, and deep in her heart she knew she had only a slim chance of avoiding being captured, tortured, and eventually killed. But she was on a mission and knew she must try.

The cold of the marble numbed her body and was icy against her cheek as she held herself closely against the surface. Why was she there? Why had she volunteered? The lonely moment caved in upon her and a desire to let go and plummet to the water swept through her—the temptation of an easy way out. It was hopeless—she should give up. She wouldn’t make it. No one could do this. How did she ever think she could?

She could feel herself beginning to loosen her grip. Any moment she would be plunging backward from the wall and it would be over. She could leave this burden for someone else, and everyone would believe she had died a heroine.

“Narda,” a soothing voice said in her head, “do not succumb to his spells. I see you. You are doing so well. You are almost there. Keep a tight grip, and continue. This is yours to do. You know you are the only one who can make this climb.” She gripped the marble tightly again, closed her large cat-like eyes and refocused her energy and mind—Yes, this is mine to do, and he cannot stop me—and upon reopening her eyes she gritted her teeth and harnessed her spirit and energy. She whispered to herself between breaths that correlated with the movement of a single limb at a time, left arm, right leg, right arm: “Half way. Under control. Keep the pace.”

She continued her ascent inches at a time. The magic she had cast upon herself neutralized Maligor’s sorcery with which he had imbued the marble to detect assailants. And beneath her chameleon cloak that made her invisible against the marble, she was imperceptible. She had only to compete with herself—her fear, her will, the burning in her limbs—in order to reach the window.

As she climbed higher, the shreds of fog swirled about her and she knew the wraiths were near, ever-searching for the warmth of life to drain from unsuspecting victims. But her cloak concealed her from them; nor was she unsuspecting. She knew her peril. She had accepted this mission—to spy on Lord Maligor to learn what he had done with the Artifacts he had stolen, and how they could be retrieved. It was a mission from which most believed she would not return. If she could just reach the window and learn something of his plans and perhaps retrieve one or two of the Artifacts, then maybe some hope might be restored in Lanedon.

Such hope rested upon this creature, no larger than an average six-year-old girl, sneaking up the side of the impossible-to-climb tower. Although small, Narda was not young. Ancient, in fact, would be a better descriptor, as her years in Lanedon were not counted in decades but in millennia. Among her people she was one of the matriarchal ancestors, revered for her wisdom, skill, and agility—the older a Muirling, the more agile and nimble. They lived in small packs that aggregated as flocks—more akin to cliff-dwelling birds due to their ability to glide upon the shoreline winds using thin membrane wings that stretched from their wrists to their ankles. Quiet as a swift, and stealthy as a tree snake, a Muirling had the prerequisites to be the most accomplished of spies, and many had become such spies and had delivered secrets and intelligence to the High Council. None, however, had stepped forward for this mission, save Narda.

She kept her ears tucked beneath the hood of her cloak, and her raven-black hair was kept in a braid down the center of her back, latched with the end of her rope-like tail. Her body was covered in short, fine hair except for her face which she had muddied on the bank of the lake so that her pale skin would not give her away, especially her long, slender nose that jutted out in a turned-up button above her small mouth. Behind her coy blue lips were jagged teeth that easily tore through the toughest of fish scales. She could be fierce, and during the course of her life and the wars against Maligor, she had been.

But now was not the time for fierceness. She must remain calm and collected, and focused on reaching the window in total secrecy. The slightest noise could attract a wraith.

“Four have been disposed of, Rogart. And now, only the sword remains,” said a tall, slender man in a deep, rich voice. His mane of wild black hair hung over his face as he stooped over an elaborate book that lay open upon a pedestal, its leather binding smooth and oiled, its pages thick and covered with drawings, thin lettering and exotic symbols. One hand he held behind his back, and with the other he traced with his finger the words upon the book, occasionally pausing to examine the artistic embellishments. He was in no rush.

“What are you waiting for, then, Lord Maligor?” asked an old raven that sat upon the branch of a dead tree off to the side of the pedestal. It was a wretched bird with bald patches where feathers had long ceased to grow—it looked like it had once been a taxidermist’s fine accomplishment, but had been played with by children, tossed into various boxes during moves, forgotten and smashed under the weight of other things, and then resurrected.

The man did not answer but continued to study the book.

A minute went by. And then another. The raven turned its head to the left, tilted it so as to view the man below more acutely, and blinked repeatedly. It waited patiently for the reply knowing better than to repeat the question.

“Rogart,” whispered the man, his words deep and now cold as a mountain lake, “I have but one opportunity to master the magic to open a portal both large and stable enough to allow the sword’s power to pass through it.”

He straightened himself, brought his hands together and touched his fingertips to his lips in contemplation of the moment. His eyes were closed. The raven did not move, but continued to blink.

When he opened his eyes they were aglow with a power that caused the entire chamber to seem to shrink before him.

“Yes,” whispered the raven in a slow croak of awe, “That is the power that is needed.”

From Maligor’s eyes a strange light flooded the room, bathing it in a dark blue light. The raven adjusted its feet and turned its head to watch with its other eye, one that was larger and covered in a white film—as if it had been plucked out and the hole covered with shiny scar tissue.

Maligor’s black lips curled and he muttered words that caused the torches to diminish, and then he spread his arms with his palms turned upward and beckoned the magic: “Power in the ore, essence of the spirit, servant of the one who has harnessed your potential—I command you once again to open the portal.”

Outside the tower the ore embedded in the rock above the tower began to vibrate at an exceedingly fast pace creating a buzzing hum. It began to glow brighter, and just as it seemed as if it might explode and cause the rock ceiling to tumble into Greneth, Maligor brought his hands together with a clap above his head. Like a lightning rod his hands attracted the energy from the ore and in a brilliant flash of dark blue light with amber streaks the energy erupted from the ore in a bolt and shot through the window into his hands.

Still thirty feet below the window, the bolt caught Narda by surprise and she cowered as much as she could against the cold marble. Fear gripped her and she nearly thrust herself from the tower, but a voice in her head soothed her again and she hugged the marble trying to recover her focus.

His hands now alit with a ball of dark blue and amber energy, Maligor strode towards a circle of stone on the floor at the center of the chamber, slightly elevated like a stage. He then stepped upon it, walked forward and gently squatted and placed the ball of energy on top of an elaborate symbol marked at the center. He stood with his hands open but close together and above it as if he were taking warmth from a fire, and then stepping backward he began to expand his hands outward and the ball of energy grew.

Rogart shifted his position again but did not take the scarred eye off the ball of energy.

Having stepped back off the stone circle, Maligor held his hands as far apart as possible. The ball of energy was now a sphere, ten feet in diameter, buzzing with the energy of the ore—a swirling mixture of dark blue light streaked with shards of amber.

Climbing as quickly as possible, Narda could see the dark blue and amber hues of the energy emanating through the window. Her heart racing, she wondered what sorcery Maligor had conjured. Ten more feet, and she would reach the window of this impossible climb. A quick glance down, and her stomach turned deep inside of her—she was so high, higher than she had ever climbed along the cliffs. The black water below churned in response to the activity in the ore. She desperately desired to be freed from this task, but having seen the energy that Maligor had summoned she knew that the High Council must learn of this. She must continue, for no one else could do it, and if she abandoned this task then Maligor would win. She was convinced that she was going to die, yet with all her strength of will she continued to scale the tower.

The wraiths disguised in the fog seemed more active and as they swooped closer to the tower Narda could feel their presence and she froze and held her breath. Would they see her somehow with this additional light from the tower refracting off the fog? Would they sense the warmth of her life, or perhaps her fear? She dared not move and remained a mere five feet below the window flattened against the tower as best as she could manage, her cheek growing numb as she pressed it hard against the cold marble. She was alone, paralyzed with fear three hundred feet high, death in every direction.

In the chamber, Maligor slowly brought his hands together again while the ball of energy remained large and in place. He stepped towards it and with his hands now palm on palm as if he were about to pray, he inserted them fingers first like a knife into the center of the ball of energy and began to expand them outward as he crisply chanted, “This world bridged to another, a portal through which to pass.”

A hole opened where he had inserted his hands and it began to grow wide as his hands drew further apart. From the hole emanated a new light—bright white, like the sunlight of Lanedon above, but this was not Lanedon. As the hole grew in size, a visage came into view: boulders lying among tall grass on the side of a gently sloping hill. At the bottom of the hill the grass was wet with a spring.

Now the gaping opening was eight feet in diameter, and Maligor gestured with his hands to fix the rim of the opening in place. He moved back from the ball of energy and breathed heavily—the portal remained, independent of him, now. The dark blue light of his eyes dimmed and his normal vision returned. His upper lip curled maliciously. Then he glanced at the raven and said, “My finest portal, yet, Rogart. Wouldn’t you agree?”