0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Passerino

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

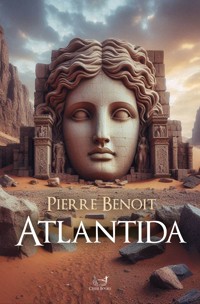

Atlantida (French:

L'Atlantide)

is a fantasy novel by French writer

Pierre Benoit, published in February 1919. It was translated into English in 1920 as

Atlantida. L'Atlantide was Benoit's second novel, following

Koenigsmark, and it won the Grand Prize of the French Academy. The English translation of Atlantida was first published in the United States as a serial in Adventure magazine.

It is 1896 in the French Algerian Sahara. Two officers, André de Saint-Avit and Jean Morhange investigate the disappearance of their fellow officers. While doing so, they are drugged and kidnapped by a Targui warrior, the procurer for the monstrous Queen Antinea.

Pierre Benoit (16 July 1886 – 3 March 1962) was a French novelist, screenwriter and member of the Académie française. He is perhaps best known for his second novel

L'Atlantide (1919) that has been filmed several times.

Translated by

Mary C. Tongue and Mary Ross.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Pierre Benoit

Atlantida

The sky is the limit

Table of contents

Preface

1. A Southern Assignment

2. Captain De Saint-Avit

3. The Morhange-Saint-Avit Mission

4. Towards Latitude 25

5. The Inscription

6. The Disaster Of The Lettuce

7. The Country Of Fear

8. Awakening At Ahaggar

9. Atlantis

10. The Red Marble Hall

11. Antinea

12. Morhange Disappears

13. The Hetman Of Jitomir’s Story

14. Hours Of Waiting

15. The Lament Of Tanit-Zerga

16. The Silver Hammer

17. The Maidens Of The Rocks

18. The Fire-Flies

19. The Tanezruft

20. The Circle Is Complete

Preface

Hassi-Inifel, November 8, 1903.

If the following pages are ever to see the light of day it will be because they have been stolen from me. The delay that I exact before they shall be disclosed assures me of that. 1

As to this disclosure, let no one distrust my aim when I prepare for it, when I insist upon it. You may believe me when I maintain that no pride of authorship binds me to these pages. Already I am too far removed from all such things. Only it is useless that others should enter upon the path from which I shall not return.

Four o’clock in the morning. Soon the sun will kindle the hamada with its pink fire. All about me the bordj is asleep. Through the half-open door of his room I hear André de Saint-Avit breathing quietly, very quietly.

In two days we shall start, he and I. We shall leave the bordj. We shall penetrate far down there to the South. The official orders came this morning.

Now, even if I wished to withdraw, it is too late. André and I asked for this mission. The authorization that I sought, together with him, has at this moment become an order. The hierarchic channels cleared, the pressure brought to bear at the Ministry;—and then to be afraid, to recoil before this adventure! . . .

To be afraid, I said. I know that I am not afraid! One night in the Gurara, when I found two of my sentinels slaughtered, with the shameful cross cut of the Berbers slashed across their stomachs,—then I was afraid. I know what fear is. Just so now, when I gazed into the black depths, whence suddenly all at once the great red sun will rise, I know that it is not with fear that I tremble. I feel surging within me the sacred horror of this mystery, and its irresistible attraction.

Delirious dreams, perhaps. The mad imaginings of a brain surcharged, and an eye distraught by mirages. The day will come, doubtless, when I shall reread these pages with an indulgent smile, as a man of fifty is accustomed to smile when he rereads old letters.

Delirious dreams. Mad imaginings. But these dreams, these imaginings, are dear to me. “Captain de Saint-Avit and Lieutenant Ferrières,” reads the official dispatch, “will proceed to Tassili to determine the stratigraphic relation of Albien sandstone and carboniferous limestone. They will, in addition, profit by any opportunities of determining the possible change of attitude of the Axdjers towards our penetration, etc.” If the journey should indeed have to do only with such poor things I think that I should never undertake it.

So I am longing for what I dread. I shall be dejected if I do not find myself in the presence of what makes me strangely fearful.

In the depths of the valley of Wadi Mia a jackal is barking. Now and again, when a beam of moonlight breaks in a silver patch through the hollows of the heat-swollen clouds, making him think he sees the young sun, a turtle dove moans among the palm trees.

I hear a step outside. I lean out of the window. A shade clad in luminous black stuff glides over the hard-packed earth of the terrace of the fortification. A light shines in the electric blackness. A man has just lighted a cigarette. He crouches, facing southwards. He is smoking.

It is Cegheir-ben-Cheikh, our Targa guide, the man who in three days is to lead us across the unknown plateaus of the mysterious Imoschaoch, across the hamadas of black stones, the great dried oases, the stretches of silver salt, the tawny hillocks, the flat gold dunes that are crested over, when the “alizé” blows, with a shimmering haze of pale sand.

Cegheir-ben-Cheikh! He is the man. There recurs to my mind Duveyrier’s tragic phrase, “At the very moment the Colonel was putting his foot in the stirrup he was felled by a sabre blow.” 2Cegheir-ben-Cheikh! There he is, peacefully smoking his cigarette, a cigarette from the package that I gave him. . . . May the Lord forgive me for it.

The lamp casts a yellow light on the paper. Strange fate, which, I never knew exactly why, decided one day when I was a lad of sixteen that I should prepare myself for Saint Cyr, and gave me there André de Saint-Avit as classmate. I might have studied law or medicine. Then I should be today a respectable inhabitant of a town with a church and running water, instead of this cotton-clad phantom, brooding with an unspeakable anxiety over this desert which is about to swallow me.

A great insect has flown in through the window. It buzzes, strikes against the rough cast, rebounds against the globe of the lamp, and then, helpless, its wings singed by the still burning candle, drops on the white paper.

It is an African May bug, big, black, with spots of livid gray.

I think of the others, its brothers in France, the golden-brown May bugs, which I have seen on stormy summer evenings projecting themselves like little particles of the soil of my native countryside. It was there that as a child I spent my vacations, and later on, my leaves. On my last leave, through those same meadows, there wandered beside me a slight form, wearing a thin scarf, because of the evening air, so cool back there. But now this memory stirs me so slightly that I scarcely raise my eyes to that dark corner of my room where the light is dimly reflected by the glass of an indistinct portrait. I realize of how little consequence has become what had seemed at one time capable of filling all my life. This plaintive mystery is of no more interest to me. If the strolling singers of Rolla came to murmur their famous nostalgic airs under the window of this bordj I know that I should not listen to them, and if they became insistent I should send them on their way.

What has been capable of causing this metamorphosis in me? A story, a legend, perhaps, told, at any rate by one on whom rests the direst of suspicions.

Cegheir-ben-Cheikh has finished his cigarette. I hear him returning with slow steps to his mat, in barrack B, to the left of the guard post.

Our departure being scheduled for the tenth of November, the manuscript attached to this letter was begun on Sunday, the first, and finished on Thursday, the fifth of November, 1903.

Olivier Ferrières, Lt. 3rd Spahis.

1. A Southern Assignment

Sunday, the sixth of June, 1903, broke the monotony of the life that we were leading at the Post of Hassi-Inifel by two events of unequal importance, the arrival of a letter from Mlle. de C——, and the latest numbers of the Official Journal of the French Republic.

“I have the Lieutenant’s permission?” said Sergeant Chatelain, beginning to glance through the magazines he had just removed from their wrappings.

I acquiesced with a nod, already completely absorbed in reading Mlle. de C——’s letter.

“When this reaches you,” was the gist of this charming being’s letter, “mama and I will doubtless have left Paris for the country. If, in your distant parts, it might be a consolation to imagine me as bored here as you possibly can be, make the most of it. The Grand Prix is over. I played the horse you pointed out to me, and naturally, I lost. Last night we dined with the Martials de la Touche. Elias Chatrian was there,—always amazingly young. I am sending you his last book, which has made quite a sensation. It seems that the Martials de la Touche are depicted there without disguise. I will add to it Bourget’s last, and Loti’s, and France’s, and two or three of the latest music hall hits. In the political word, they say the law about congregations will meet with strenuous opposition. Nothing much in the theatres. I have taken out a summer subscription for l’Illustration. Would you care for it? In the country no one knows what to do. Always the same lot of idiots ready for tennis. I shall deserve no credit for writing to you often. Spare me your reflections concerning young Combemale. I am less than nothing of a feminist, having too much faith in those who tell me that I am pretty, in yourself in particular. But indeed, I grow wild at the idea that if I permitted myself half the familiarities with one of our lads that you have surely with your Ouled-Nails . . Enough of that, it is too unpleasant an idea.”

I had reached this point in the prose of this advanced young woman when a scandalized exclamation of the Sergeant made me look up.

“Lieutenant!”

“Yes?”

“They are up to something at the Ministry. See for yourself.”

He handed me the Official. I read:

“By a decision of the first of May, 1903, Captain de Saint-Avit (André), unattached, is assigned to the Third Spahis, and appointed Commandant of the Post of Hassi-Inifel.”

Chatelain’s displeasure became fairly exuberant.

“Captain de Saint-Avit, Commandant of the Post. A post which has never had a slur upon it. They must take us for a dumping ground.”

My surprise was as great as the Sergeant’s. But just then I saw the evil, weasel-like face of Gourrut, the convict we used as clerk. He had stopped his scrawling and was listening with a sly interest.

“Sergeant, Captain de Saint-Avit is my ranking classmate,” I answered dryly.

Chatelain saluted, and left the room. I followed.

“There, there,” I said, clapping him on the back, “no hard feelings. Remember that in an hour we are starting for the oasis. Have the cartridges ready. It is of the utmost importance to restock the larder.”

I went back to the office and motioned Gourrut to go. Left alone, I finished Mlle. de C——’s letter very quickly, and then reread the decision of the Ministry giving the post a new chief.

It was now five months that I had enjoyed that distinction, and on my word, I had accepted the responsibility well enough, and been very well pleased with the independence. I can even affirm, without taking too much credit for myself, that under my command discipline had been better maintained than under Captain Dieulivol, Saint-Avit’s predecessor. A brave man, this Captain Dieulivol, a non-commissioned officer under Dodds and Duchesne, but subject to a terrible propensity for strong liquors, and too much inclined, when he had drunk, to confuse his dialects, and to talk to a Houassa in Sakalave. No one was ever more sparing of the post water supply. One morning when he was preparing his absinthe in the presence of the Sergeant, Chatelain, noticing the Captain’s glass, saw with amazement that the green liquor was blanched by a far stronger admixture of water than usual. He looked up, aware that something abnormal had just occurred. Rigid, the carafe inverted in his hand, Captain Dieulivol was spilling the water which was running over on the sugar. He was dead.

For six months, since the disappearance of this sympathetic old tippler, the Powers had not seemed to interest themselves in finding his successor. I had even hoped at times that a decision might be reached investing me with the rights that I was in fact exercising. . . . And today this surprising appointment.

Captain de Saint-Avit. He was of my class at St. Cyr. I had lost track of him. Then my attention had been attracted to him by his rapid advancement, his decoration, the well-deserved recognition of three particularly daring expeditions of exploration to Tebesti and the Air; and suddenly, the mysterious drama of his fourth expedition, that famous mission undertaken with Captain Morhange, from which only one of the explorers came back. Everything is forgotten quickly in France. That was at least six years ago. I had not heard Saint-Avit mentioned since. I had even supposed that he had left the army. And now, I was to have him as my chief.

“After all, what’s the difference,” I mused, “he or another! At school he was charming, and we have had only the most pleasant relationships. Besides, I haven’t enough yearly income to afford the rank of Captain.”

And I left the office, whistling as I went.

We were now, Chatelain and I, our guns resting on the already cooling earth, beside the pool that forms the center of the meager oasis, hidden behind a kind of hedge of alfa. The setting sun was reddening the stagnant ditches which irrigate the poor garden plots of the sedentary blacks.

Not a word during the approach. Not a word during the shoot. Chatelain was obviously sulking.

In silence we knocked down, one after the other, several of the miserable doves which came on dragging wings, heavy with the heat of the day, to quench their thirst at the thick green water. When a half-dozen slaughtered little bodies were lined up at our feet I put my hand on the Sergeant’s shoulder.

“Chatelain!”

He trembled.

“Chatelain, I was rude to you a little while ago. Don’t be angry. It was the bad time before the siesta. The bad time of midday.”

“The Lieutenant is master here,” he answered in a tone that was meant to be gruff, but which was only strained.

“Chatelain, don’t be angry. You have something to say to me. You know what I mean.”

“I don’t know really. No, I don’t know.”

“Chatelain, Chatelain, why not be sensible? Tell me something about Captain de Saint-Avit.”

“I know nothing.” He spoke sharply.

“Nothing? Then what were you saying a little while ago?”

“Captain de Saint-Avit is a brave man.” He muttered the words with his head still obstinately bent. “He went alone to Bilma, to the Air, quite alone to those places where no one had ever been. He is a brave man.”

“He is a brave man, undoubtedly,” I answered with great restraint. “But he murdered his companion, Captain Morhange, did he not?”

The old Sergeant trembled.

“He is a brave man,” he persisted.

“Chatelain, you are a child. Are you afraid that I am going to repeat what you say to your new Captain?”

I had touched him to the quick. He drew himself up.

“Sergeant Chatelain is afraid of no one, Lieutenant. He has been at Abomey, against the Amazons, in a country where a black arm started out from every bush to seize your leg, while another cut it off for you with one blow of a cutlass.”

“Then what they say, what you yourself—”

“That is talk.”

“Talk which is repeated in France, Chatelain, everywhere.”

He bent his head still lower without replying.

“Ass,” I burst out, “will you speak?”

“Lieutenant, Lieutenant,” he fairly pled, “I swear that what I know, or nothing—”

“What you know you are going to tell me, and right away. If not, I give you my word of honor that, for a month, I shall not speak to you except on official business.”

Hassi-Inifel: thirty native Arabs and four Europeans—myself, the Sergeant, a Corporal, and Gourrut. The threat was terrible. It had its effect.

“All right, then, Lieutenant,” he said with a great sigh. “But afterwards you must not blame me for having told you things about a superior which should not be told and come only from the talk I overheard at mess.”

“Tell away.”

“It was in 1899. I was then Mess Sergeant at Sfax, with the 4th Spahis. I had a good record, and besides, as I did not drink, the Adjutant had assigned me to the officers’ mess. It was a soft berth. The marketing, the accounts, recording the library books which were borrowed (there weren’t many), and the key of the wine cupboard,—for with that you can’t trust orderlies. The Colonel was young and dined at mess. One evening he came in late, looking perturbed, and, as soon as he was seated, called for silence:

“‘Gentlemen,’ he said, ‘I have a communication to make to you, and I shall ask for your advice. Here is the question. Tomorrow morning the City of Naples lands at Sfax. Aboard her is Captain de Saint-Avit, recently assigned to Feriana, en route to his post.’

“The Colonel paused. ‘Good,’ thought I, ‘tomorrow’s menu is about to be considered.’ For you know the custom, Lieutenant, which has existed ever since there have been any officers’ clubs in Africa. When an officer is passing by, his comrades go to meet him at the boat and invite him to remain with them for the length of his stay in port. He pays his score in news from home. On such occasions everything is of the best, even for a simple lieutenant. At Sfax an officer on a visit meant—one extra course, vintage wine and old liqueurs.

“But this time I imagined from the looks the officers exchanged that perhaps the old stock would stay undisturbed in its cupboard.

“You have all, I think, heard of Captain de Saint-Avit, gentlemen, and the rumors about him. It is not for us to inquire into them, and the promotion he has had, his decoration if you will, permits us to hope that they are without foundation. But between not suspecting an officer of being a criminal, and receiving him at our table as a comrade, there is a gulf that we are not obliged to bridge. That is the matter on which I ask your advice.’

“There was silence. The officers looked at each other, all of them suddenly quite grave, even to the merriest of the second lieutenants. In the corner, where I realized that they had forgotten me, I tried not to make the least sound that might recall my presence.

“‘We thank you, Colonel,’ one of the majors finally replied, ‘for your courtesy in consulting us. All my comrades, I imagine, know to what terrible rumors you refer. If I may venture to say so, in Paris at the Army Geographical Service, where I was before coming here, most of the officers of the highest standing had an opinion on this unfortunate matter which they avoided stating, but which cast no glory upon Captain de Saint-Avit.’

“‘I was at Bammako, at the time of the Morhange-Saint-Avit mission,’ said a Captain. ‘The opinion of the officers there, I am sorry to say, differed very little from what the Major describes. But I must add that they all admitted that they had nothing but suspicions to go on. And suspicions are certainly not enough considering the atrocity of the affair.’

“‘They are quite enough, gentlemen,’ replied the Colonel, ‘to account for our hesitation. It is not a question of passing judgment; but no man can sit at our table as a matter of right. It is a privilege based on fraternal esteem. The only question is whether it is your decision to accord it to Saint-Avit.’

“So saying, he looked at the officers, as if he were taking a roll call. One after another they shook their heads.

“‘I see that we agree,’ he said. ‘But our task is unfortunately not yet over. The City of Naples will be in port tomorrow morning. The launch which meets the passengers leaves at eight o’clock. It will be necessary, gentlemen, for one of you to go aboard. Captain de Saint-Avit might be expecting to come to us. We certainly have no intention of inflicting upon him the humiliation of refusing him, if he presented himself in expectation of the customary reception. He must be prevented from coming. It will be wisest to make him understand that it is best for him to stay aboard.’

“The Colonel looked at the officers again. They could not but agree. But how uncomfortable each one looked!

“‘I cannot hope to find a volunteer among you for this kind of mission, so I am compelled to appoint some one. Captain Grandjean, Captain de Saint-Avit is also a Captain. It is fitting that it be an officer of his own rank who carries him our message. Besides, you are the latest corner here. Therefore it is to you that I entrust this painful interview. I do not need to suggest that you conduct it as diplomatically as possible.’

“Captain Grandjean bowed, while a sigh of relief escaped from all the others. As long as the Colonel stayed in the room Grandjean remained apart, without speaking. It was only after the chief had departed that he let fall the words:

“‘There are some things that ought to count a good deal for promotion.’

“The next day at luncheon everyone was impatient for his return.

“‘Well?’ demanded the Colonel, briefly.

“Captain Grandjean did not reply immediately. He sat down at the table where his comrades were mixing their drinks, and he, a man notorious for his sobriety, drank almost at a gulp, without waiting for the sugar to melt, a full glass of absinthe.

“‘Well, Captain?’ repeated the Colonel.

“‘Well, Colonel, it’s done. You can be at ease. He will not set foot on shore. But, ye gods, what an ordeal!’

“The officers did not dare speak. Only their looks expressed their anxious curiosity.

“Captain Grandjean poured himself a swallow of water.

“‘You see, I had gotten my speech all ready, in the launch. But as I went up the ladder I knew that I had forgotten it. Saint-Avit was in the smoking-room, with the Captain of the boat. It seemed to me that I could never find the strength to tell him, when I saw him all ready to go ashore. He was in full dress uniform, his sabre lay on the bench and he was wearing spurs. No one wears spurs on shipboard. I presented myself and we exchanged several remarks, but I must have seemed somewhat strained for from the first moment I knew that he sensed something. Under some pretext he left the Captain, and led me aft near the great rudder wheel. There, I dared speak. Colonel, what did I say? How I must have stammered! He did not look at me. Leaning his elbows on the railing he let his eyes wander far off, smiling slightly. Then, of a sudden, when I was well tangled up in explanations, he looked at me coolly and said:

“‘“I must thank you, my dear fellow, for having given yourself so much trouble. But it is quite unnecessary. I am out of sorts and have no intention of going ashore. At least, I have the pleasure of having made your acquaintance. Since I cannot profit by your hospitality, you must do me the favor of accepting mine as long as the launch stays by the vessel.”

“‘Then we went back to the smoking-room. He himself mixed the cocktails. He talked to me. We discovered that we had mutual acquaintances. Never shall I forget that face, that ironic and distant look, that sad and melodious voice. Ah! Colonel, gentlemen, I don’t know what they may say at the Geographic Office, or in the posts of the Soudan. . . . There can be nothing in it but a horrible suspicion. Such a man, capable of such a crime,—believe me, it is not possible.’

“That is all, Lieutenant,” finished Chatelain, after a silence. “I have never seen a sadder meal than that one. The officers hurried through lunch without a word being spoken, in an atmosphere of depression against which no one tried to struggle. And in this complete silence, you could see them always furtively watching the City of Naples, where she was dancing merrily in the breeze, a league from shore.

“She was still there in the evening when they assembled for dinner, and it was not until a blast of the whistle, followed by curls of smoke escaping from the red and black smokestack had announced the departure of the vessel for Gabes, that conversation was resumed; and even then, less gaily than usual.

“After that, Lieutenant, at the Officers’ Club at Sfax, they avoided like the plague any subject which risked leading the conversation back to Captain de Saint-Avit.”

Chatelain had spoken almost in a whisper, and the little people of the desert had not heard this singular history. It was an hour since we had fired our last cartridge. Around the pool the turtle doves, once more reassured, were bathing their feathers. Mysterious great birds were flying under the darkening palm trees. A less warm wind rocked the trembling black palm branches. We had laid aside our helmets so that our temples could welcome the touch of the feeble breeze.

“Chatelain,” I said, “it is time to go back to the bordj.”

Slowly we picked up the dead doves. I felt the Sergeant looking at me reproachfully, as if regretting that he had spoken. Yet during all the time that our return trip lasted, I could not find the strength to break our desolate silence with a single word.

The night had almost fallen when we arrived.

The flag which surmounted the post was still visible, drooping on its standard, but already its colors were indistinguishable. To the west the sun had disappeared behind the dunes gashed against the black violet of the sky.

When we had crossed the gate of the fortifications, Chatelain left me.

“I am going to the stables,” he said.

I returned alone to that part of the fort where the billets for the Europeans and the stores of ammunition were located. An inexpressible sadness weighed upon me.

I thought of my comrades in French garrisons.

At this hour they must be returning home to find awaiting them, spread out upon the bed, their dress uniform, their braided tunic, their sparkling epaulettes.

“Tomorrow,” I said to myself, “I shall request a change of station.”

The stairway of hard-packed earth was already black. But a few gleams of light still seemed palely prowling in the office when I entered.

A man was sitting at my desk, bending over the files of orders. His back was toward me. He did not hear me enter.

“Really, Gourrut, my lad, I beg you not to disturb yourself. Make yourself completely at home.”

The man had risen, and I saw him to be quite tall, slender and very pale.

“Lieutenant Ferrières, is it not?” He advanced, holding out his hand.

“Captain de Saint-Avit. Delighted, my dear fellow.”

At the same time Chatelain appeared on the threshold.

“Sergeant,” said the newcomer, “I cannot congratulate you on the little I have seen. There is not a camel saddle which is not in want of buckles, and they are rusty enough to suggest that it rains at Hassi-Inifel three hundred days in the year. Furthermore, where were you this afternoon? Among the four Frenchmen who compose the post, I found only on my arrival one convict, opposite a quart of eau-de-vie. We will change all that, I hope. At ease.”

“Captain,” I said, and my voice was colorless, while Chatelain remained frozen at attention, “I must tell you that the Sergeant was with me, that it is I who am responsible for his absence from the post, that he is an irreproachable non-commissioned officer from every point of view, and that if we had been warned of your arrival—”

“Evidently,” he said, with a coldly ironical smile. “Also, Lieutenant, I have no intention of holding him responsible for the negligences which attach to your office. He is not obliged to know that the officer who abandons a post like Hassi-Inifel, if it is only for two hours, risks not finding much left on his return. The Chaamba brigands, my dear sir, love firearms, and for the sake of the sixty muskets in your racks, I am sure they would not scruple to make an officer, whose otherwise excellent record is well known to me, account for his absence to a court-martial. Come with me, if you please. We will finish the little inspection I began too rapidly a little while ago.”

He was already on the stairs. I followed in his footsteps. Chatelain closed the order of march. I heard him murmuring, in a tone which you can imagine:

“Well, we are in for it now!”

2. Captain De Saint-Avit

A few days sufficed to convince us that Chatelain’s fears as to our official relations with the new chief were vain. Often I have thought that by the severity he showed at our first encounter Saint-Avit wished to create a formal barrier, to show us that he knew how to keep his head high in spite of the weight of his heavy past. Certain it is that the day after his arrival, he showed himself in a very different light, even complimenting the Sergeant on the upkeep of the post and the instruction of the men. To me he was charming.

“We are of the same class, aren’t we?” he said to me. “I don’t have to ask you to dispense with formalities, it is your right.”

Vain marks of confidence, alas! False witnesses to a freedom of spirit, one in face of the other. What more accessible in appearance than the immense Sahara, open to all those who are willing to be engulfed by it? Yet what is more secret? After six months of companionship, of communion of life such as only a Post in the South offers, I ask myself if the most extraordinary of my adventures is not to be leaving to-morrow, toward unsounded solitudes, with a man whose real thoughts are as unknown to me as these same solitudes, for which he has succeeded in making me long.

The first surprise which was given me by this singular companion was occasioned by the baggage that followed him.

On his inopportune arrival, alone, from Wargla, he had trusted to the Mehari he rode only what can be carried without harm by such a delicate beast,—his arms, sabre and revolver, a heavy carbine, and a very reduced pack. The rest did not arrive till fifteen days later, with the convoy which supplied the post.

Three cases of respectable dimensions were carried one after another to the Captain’s room, and the grimaces of the porters said enough as to their weight.

I discreetly left Saint-Avit to his unpacking and began opening the mail which the convoy had sent me.

He returned to the office a little later and glanced at the several reviews which I had just received. “So,” he said. “You take these.”

He skimmed through, as he spoke, the last number of the Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft fur Erdkunde in Berlin.

“Yes,” I answered. “These gentlemen are kind enough to interest themselves in my works on the geology of the Wadi Mia and the high Igharghar.”

“That may be useful to me,” he murmured, continuing to turn over the leaves.

“It’s at your service.”

“Thanks. I am afraid I have nothing to offer you in exchange, except Pliny, perhaps. And still—you know what he said of Igharghar, according to King Juba. However, come help me put my traps in place and you will see if anything appeals to you.”

I accepted without further urging.

We commenced by unearthing various meteorological and astronomical instruments—the thermometers of Baudin, Salleron, Fastre, an aneroid, a Fortin barometer, chronometers, a sextant, an astronomical spyglass, a compass glass. . . . In short, what Duveyrier calls the material that is simplest and easiest to transport on a camel.

As Saint-Avit handed them to me I arranged them on the only table in the room.

“Now,” he announced to me, “there is nothing more but books. I will pass them to you. Pile them up in a corner until I can have a book-shelf made.”

For two hours altogether I helped him to heap up a real library. And what a library! Such as never before a post in the South had seen. All the texts consecrated, under whatever titles, by antiquity to the regions of the Sahara were reunited between the four rough-cast walls of that little room of the bordj. Herodotus and Pliny, naturally, and likewise Strabo and Ptolemy, Pomponius Mela, and Ammien Marcellin. But besides these names which reassured my ignorance a little, I perceived those of Corippus, of Paul Orose, of Eratosthenes, of Photius, of Diodorus of Sicily, of Solon, of Dion Cassius, of Isidor of Seville, of Martin de Tyre, of Ethicus, of Athenée, the Scriptores Historiae Augustae, the Itinerarium Antonini Augusti, the Geographi Latini Minores of Riese, the Geographi Graeci Minores of Karl Muller. . . . Since I have had the occasion to familiarize myself with Agatarchides of Cos and Artemidorus of Ephesus, but I admit that in this instance the presence of their dissertations in the saddle bags of a captain of cavalry caused me some amazement.

I mention further the Descrittione dell’ Africa by Leon l’African, the Arabian Histories of Ibn-Khaldoun, of Al-Iagoub, of El-Bekri, of Ibn-Batoutah, of Mahommed El-Tounsi. . . . In the midst of this Babel, I remember the names of only two volumes of contemporary French scholars. There were also the laborious theses of Berlioux 3 and of Schirmer.4

While I proceeded to make piles of as similar dimensions as possible I kept saying to myself:

“To think that I have been believing all this time that in his mission with Morhange, Saint-Avit was particularly concerned in scientific observations. Either my memory deceives me strangely or he is riding a horse of another color. What is sure is that there is nothing for me in the midst of all this chaos.”

He must have read on my face the signs of too apparently expressed surprise, for he said in a tone in which I divined a tinge of defiance:

“The choice of these books surprises you a bit?”

“I can’t say it surprises me,” I replied, “since I don’t know the nature of the work for which you have collected them. In any case I dare say, without fear of being contradicted, that never before has officer of the Arabian Office possessed a library in which the humanities were so well represented.”

subjHe smiled evasively, and that day we pursued the ect no further. Among Saint-Avit’s books I had noticed a volu-

minous notebook secured by a strong lock. Several times I surprised him in the act of making notations in it. When for any reason he was called out of the room he placed this album carefully in a small cabinet of white wood, provided by the munificence of the Administration. When he was not writing and the office did not require his presence, he had the mehari which he had brought with him saddled, and a few minutes later, from the terrace of the fortifications, I could see the double silhouette disappearing with great strides behind a hummock of red earth on the horizon.

Each time these trips lasted longer. From each he returned in a kind of exaltation which made me watch him with daily increasing disquietude during meal hours, the only time we passed quite alone together.

“Well,” I said to myself one day when his remarks had been more lacking in sequence than usual, “it’s no fun being aboard a submarine when the captain takes opium. What drug can this fellow be taking, anyway?”

Next day I looked hurriedly through my comrade’s drawers. This inspection, which I believed to be my duty, reassured me momentarily. “All very good,” I thought, “provided he does not carry with him his capsules and his Pravaz syringe.”

pig I was still in that stage where I could suppose that André’s imagination needed artificial stimulants. Meticulous observation undeceived me. There was nothing suspicious in this respect. Moreover, he rarely drank and almost never smoked.

And nevertheless, there was no means of denying the increase of his disquieting feverishness. He returned from his expeditions each time with his eyes more brilliant. He was paler, more animated, more irritable.

One evening he left the post about six o’clock, at the end of the greatest heat of the day. We waited for him all night. My anxiety was all the stronger because quite recently caravans had brought tidings of bands of robbers in the neighborhood of the post.

At dawn he had not returned. He did not come before midday. His camel collapsed under him, rather than knelt.