Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CASSAVA REPUBLIC

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

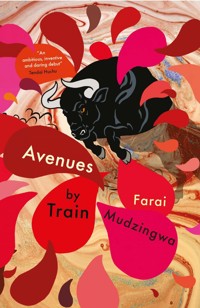

When seven-year-old Jedza witnesses a tragic incident involving a train and the death of his close boyhood friend in his hometown Miner’s Drift, he is convinced that his life is haunted. Now in his mid-20s, Jedza is a down-and-out electrician, moving to Harare in the hopes that he will escape the darkness and superstitions of the small town. But living in the shadowy restless atmosphere of the Avenues with its mysterious pools of water rising under musasa trees, he is tormented by the disappearance of his sister and their early encounters with ancestral spirits, the shapeshifting power of the njuzu and a vengeful ngozi. To move forward, he must stop running away and confront the trauma of his past. An eclectic, experimental novel, Avenues By Train is a brash and confident debut by an exciting new voice

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 440

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

AVENUES BY TRAIN

Farai Mudzingwa

Dedication

To Annastasia and Alexio Noah whose presence is stronger with the passage of time.

Akuruma nzeve ndewako

Contents

1

1974

Listen, when the ancestors bite your ears. Natsai and her friends raced across the foot bridge on their way from the early morning Roman Catholic Church mass and teased whoever came last.

“Whoever is left behind is left behind,” the same voice blurts out again.

“Onyo marks!”

“Seti, seti …”

“Go!”

Theresa was the slowest kid. She wheezed all the way down the foot path. Their little heads disappeared into the reeds along the stream and only their shrieks and squeals sounded until they popped up on the home side.

On this April school holiday Sunday, on which they stopped by the shops on their way back from church and each bought a loaf of white bread for morning tea, six kids emerged panting and giggling on the other side of the stream. Theresa did not.

She dances,

Come see,2

In her watery den,

She dances…

As the kids reported the incident to their parents, Natsai rubbed her ankle where the njuzu had grasped at her, before she had slipped through and it had reached for Theresa instead.

A watery viscous hand slides up out of the water and webbed fingers run up her foot. The prehensile grip around her ankle tightens.

Fingers so cold they register as a burning sensation. A jolt, an electric shock of feeling, shoots up her leg.

The elders sighed and word spread from mouth to ear around Miner’s Drift, that another one had been taken.1

After this taking, as with the others before it, parents forbade their children from walking across the wetland or wandering near the stream and the deep pool near the narrow footbridge. “Take the longer route over the vehicle bridge,” they cautioned. “That family, those ones, they don’t pray properly; that’s why these things happen to them,” said others.

Theresa’s family gathered and performed a bira renjuzu at the pool to appease the water being. During the bira, the spirit of the taken child whispered from the watery depths, and through vigorous dance, the family elders learned what they needed to sacrifice before the njuzu would release the child. It took the better part of a week to source a goat, and in more costly fashion, the requisite mature black bull. “She is of VaDziva,” they chanted in unison to the water entity. “We are kin,” they pled, while clapping in sombre rhythm. Not a single tear was shed, for shedding tears would seal her fate. 3And so it was, that after days of carrying out these and other rituals, she was returned to the surface unharmed, poised for life as a healer.

As the gathered petitioners wipe the water from their eyes and wring out their garments, they catch sight of a little girl crawling up the bank on her hands and knees. She has emerged at the edge of the pool, water streaming and dripping from her, her thin dress clinging to her drenched body. The child is gasping as she tries to adjust to breathing the thin air above the surface.

Theresa’s mother rushes to embrace her. The faraway gaze in the child’s unblinking eyes does not alter.

Back home, Natsai sat rubbing her ankle, “Mai, they are saying that if it touches you then you are now a bad person.”

“Those are witchcraft things my child. Let them touch each other there where they do those things at night.”

“Asi Mai…”

“Ah you Natsai, what is it with you today?”

Natsai started to raise her foot up to show her mother the mark on her ankle. “The thing, it was crying. I think it was trying to say something.”

“Do not talk about those heathen things in this house, do you hear me Natsai? We pray in this house. People who believe in those njuzu things do the works of darkness. If you were another person you would bring me my rosary so we can pray right now.”

1 Miner’s Drift was named after Henry Miner, the biggest and worst poacher in all history. Killed 1 200 elephants “on horseback”. Died instantly when a rhino he was trying to shoot sat on his face.

2

Tracks Of My Fears, 1984

Ride with me. I’m about seven years old with a shiny bald head courtesy of a weekend visit to Miner’s Drift by my grandma Mbuya Maswiti and her razor blade.2

Everyone calls me Gerry.

I have a squad. Dalitso, Takunda and me. Takunda’s parents own the Continental Supermarket and he is forever telling us how busy his father is “bal-an-cing the books”. Dalitso’s parents run Chinopisa Bakery which bakes shiny sugar buns for the whole town. My parents are both civil servants at The Ministry and also devout members of the Roman Catholic Church. Father sings in the choir (between me and you, he does this to get Mother off his back) and Mother prepares the girls for marriage. My older sister Natsai is cool.

5Walking in town with Father is such a gas. I lead the way and he is right behind me with a steady clippity-clop of his leather shoes and his Farmer’s Weekly tucked under his arm. Every so often he will clear his throat and I will adjust my pace accordingly. All too often, he will come to a complete stop as he chats to people. They will make way for me and then greet him. He will enquire, “Ah, Mr So-and So, how is the family? Ah, Comrade So-and-So, how was such-and-such meeting?” And then he will say, “Ah, work is work. But there is always more to be done.” And then he will tap his magazine and comment on how the rains are late this year or how the country needs a winter crop. Or, in a lowered voice, and only to a select few, how certain things in the country are not how they should be, given what we have been through. When he is done, he will clear his throat and we take off down the pavement.

After weeks of pleading and promises to be good, he agrees to buy me a bicycle from Zambesia Cycles next to the Post Office. The owner of the shop is this hunched man with windblown grey hair who lives above his shop and sits behind the counter during the day. He puffs away at a pipe in his mouth which he only pulls out to bark at his assistant. His shop assistant, who does all the talking for him, is forever chasing our squad away from the shop front when all we’re trying to do is catch a glimpse of the new bikes in the window. That guy deserves what’s coming his way, if you know what I mean.

On the day that we come in to buy my bike, I strut into the shop with my shorts pulled high and my chest full of air. The assistant glances down at me, purses his lips, then greets Father. Father says, “Ah Comrade, how are things in your establishment? Are things going well?” The assistant wipes his brow, then looks over at the man behind the till, then back at Father. Father puts a hand in his pocket and starts whistling while looking around the shop. The assistant stiffens and creaks over to the old man. The pipe comes out 6of the owner’s mouth while the assistant explains with the help of his hands. The pipe hovers outside the downturned mouth and the assistant’s hands keep gesturing. In the end, the pipe is placed on the counter and the owner drags his feet over to Father.

Father gets straight to the point. “My son wants a bike. What do you have for someone his age?”

The owner rattles off words I don’t understand. Here and there, I pick up a word in English. He uses a lot of hand gestures as if his upturned hands could speak for him. Father seems to understand him but replies mostly in English. Here and there, the owner glances over at the shop assistant and Father stares down the owner who mumbles something under his breath before carrying on. The shop assistant keeps shifting from one foot to the other like a gum tree swaying in the wind. Father taps his magazine when the old man speaks, and other times, lets out a drawn-out whistle, all the while with his other hand in his pocket. This man’s style is something else, I tell you.

There are only two options: either the Choppers or the regular Twenties. I run my fingers along the long Chopper handlebars and Father clears his throat. I slide over to the Twenties. I seat myself on a red bike and it feels just right. The seat is a bit stiff but it will do. When flicked, the bell chimes and echoes around the shop. That seals the deal. Father does what Father does and I wheel my new red bike out of the shop, he tucks his Farmer’s Weekly back under his arm, and the pipe goes back into the owner’s mouth.

Walking down the street, I ask Father about the old man and Father says that he’s from far down the highway, from a town called Tete along the Zambezi River in Mozambique, and that he only speaks ChiPutukezi.3 “He is one of those who 7refuses to accept that times have changed,” Father adds. I ring my bell twice.

***

My squad and I are in our final year at Little Mermaids Nursery School. Our teachers can’t wait for us to leave. My role in the squad is one of charm and persuasion, if you know what I mean. I get us in and out of trouble. Dalitso could whip Takunda and I with two fingers of his left hand while taking gulps of milk in the other hand and bal-an-cing a football on his right foot, but he humours us and lets us get away with all kinds of nonsense. Takunda’s family is rich. He’s the bank, I’m the sweet talk and Dalitso is the muscle. So this is my crew when we set off on our cycles, on a journey across town to Pfumojena township, venturing into territory far from what is familiar to us, so I can show them the stream where the njuzu lives.4

Dalitso is taller and broader than all the other boys but he never fights or argues with anyone. He has this calm, steady manner that I copy and aim to improve each time we hang out. He doesn’t punch Takunda at times when Takunda should be punched, which tends to annoy me. Dalitso sometimes comes to school wearing his showy clothes. He wears a small cloth cap on his head, a jacket with long sleeves, and long pants all made of the same shiny fabric. His dad wears similar clothes, his mom wears full black. On these days the other kids at Little Mermaids tease him. Takunda used to lead the taunts. That’s one of the times Dalitso should have punched his teeth out, but he didn’t. I 8think Dalitso’s clothes are cool. That’s also why we became friends. Takunda stopped laughing at Dalitso’s clothes when he realised that I had started hanging out with him and then we all started hanging out together.

***

Sisi Natsai told me about the njuzu that lives in the stream near our old house in Pfumojena township. She also showed me the strange marks on her ankle where she says it touched her when she was little. Three tiny dark lines that never fade: she says those are the njuzu’s fingertips. She has been marked and it must mean something, she says. She made me promise not to speak to Mother or Father about the marks. Of course, I did tell the kids at Little Mermaids Nursery School the following day, as one does. The atmosphere at breaktime was highly charged. Most of them didn’t believe me though. The kids who did believe me were scared senseless of the njuzu. They too had heard the stories about young girls being taken underwater. A current hummed through their minds and little sparks of fear kept them on edge.

***

Electricity. That energy that bridges the divide between what is scientific and technological and magic. That’s the reason the colonisers challenged the gods of nature when they built Kariba dam to create hydro-electric energy. Electricity to power industry, commerce, indeed technological modernity, and electric trains to more efficiently shunt resources to the ports and up to the metropole. Trains that weren’t there to carry people but made for raw materials and munitions, routes from mines to factories to towns. The first trains were those beast-drawn wagons that circled and laagered and fired seven-pounder cannons right up to Fort Salisbury. Unlike those Batonga living on the Zambezi who resisted the damming of the great river, who would oppose and 9want nothing to do with this brand of modernity, the local people along the wagon routes embraced or succumbed to the invaders and sought work on the railways, the most ambitious attaining the station of the wagon driver. At the time, the wagon driver was the envy of other men and the heart’s desire of women. The one who rode in on the beast of modernity and whose wife, it is said, cooked only with the poshest of oils, grease, as they called it then.

***

Takunda’s father has just bought a brand-new white Peugeot 504 sedan and he’s now getting all the attention at Little Mermaids when his dad drops him off.5 I could be chatting away with little Tari Makanda, showing her what I have in my lunch box, when guess-who swings by asking her if she wants to ride in his father’s car at pick-up time? Such a show off, I tell you. Takunda also has a new skateboard and the girls do not notice me anymore. It is under these pressing circumstances that I announce that I have passed by the njuzu’s stream, seen the water spirit on many occasions and will take the squad there if they aren’t afraid.

Gasps and squeaks ring out across the playground; swings hang mid-air with frozen kids suspended in them; Mandy Wilson’s ponytail shoots up straight above her head in fear; Taka Moyo tries to clench his little bum but the frightened farts shoot out of his tiny Adidas shorts in rapid bursts; Mrs Dube steps out onto the verandah, swinging the bell to end breaktime but no one moves; a gust of wind blows up little Tari Makanda’s yellow skirt but none of the boys giggle. Takunda clears his throat. I look across at him.

“Let’s go see it,” he stammers bravely.

10“Let’s,” I say.

***

Where the gods may anger then forgive, nature tends towards patience and measured wrath. Hubris brings catastrophe, the world spins off-balance. Take for instance the series of gas explosions ripping up from deep in the bowels of the earth at Wankie No. 2 Colliery in June of 1972. Resulting in 424 miners’ bodies forever sealed in a carbon tomb. It is almost as if some deity held a grudge carried over from the floods on the Zambezi of 1957 and 1958, and feeling slighted, decided to thwart whichever energy source these humans need to power their brand of civilisation or drive their locomotives. It is almost as if the earth does not approve of its belly being excavated or its riverine lifelines being choked and harnessed.

And so, on this specific morning in 1984, despite all the warnings that the spirits have given to the unhearing, an electric train departs from Harare. The wagon driver, posh as his earlier incarnations may have been, is posher still as the driver of an electric locomotive of the National Railways of Zimbabwe. This lively chap has awoken in a sweaty bout of coughing, then left his dwelling in Chenga Ose, an aspirational residential development on the outskirts of the city already showing signs of decline, to jog, splutter and gasp through the early morning crowds striding towards the bus stop, stale beer still on his breath, the pungent smell of a greasy perm stuck in his nostrils, as is the cheap perfume of last night’s special friend, someone he cannot wait to get back to in a couple of days’ time. His trotting gait gets shorter as his chest gets tighter and his breathing raspier. At one point, he bends over on the side of the road and grasps his knees while dry heaving and forcing out wheezes that culminate in a high-pitched whine. Too many smokers in the bar last night, he tells himself. The air is too dry and cold today, he mumbles to a passerby who shakes her head and steers 11clear of him. Four months just coughing, he grimaces, while standing up straight again and taking off towards the bus that awaits him.

***

Back in Miner’s Drift, I’m the first to get going on this bright morning. Dalitso is dressed in his white tunic and wheeling around in his driveway when I roll up to his gate. I punch him in the shoulder and he laughs, then punches me back. He has held back on the punch but I still wince and blink. “Are you okay, Gerry? Sorry, shaa.”

“Haa, it’s not sore. Don’t worry.” I blink away tears.

“Do you want to see my grandpa? He’s sitting in the sun outside the cottage.”

“Not now, Dali. We need to go. Remember we are on a mission today?”

Dalitso starts wringing his hands.

“Okay, but I promised Sekuru Jairos I would sit with him today.”

“He will be here when we get back. Are you afraid now? Should I tell everyone at school that Dali is afraid?”

He shuts his eyes and works out his thoughts on his fingers. I know not to interrupt him because that will just make him start all over again. I shuffle my feet and look around the garden. There is some movement in one window but I can’t quite make out who or what it might be. Little birds dart and dive between shrubs. A gecko bobs its head up on a rockery. “Gum-kum, bang your head on the rock, Gum-kum, bang your head on the rock,” I chant to myself a few times. Stubborn little fellow refuses to oblige me. I saunter across the driveway and peek behind the house to the cottage and sure enough, Dalitso’s grandpa is slumped in an armchair with his head tilted at an angle to catch the sun rays on his stubbly chin. A newspaper has slid off his lap and lies at his feet, pages threatening to flip open in the breeze. Dalitso releases a long breath. “Let’s wrestle.” 12

“What?”

“Let’s wrestle. If you win, we leave straight away. But if I win, then we go and sit with my grandpa.”

“No, I don’t want to wrestle you. You’re too big.” He’s a mountain of a chap, I tell you.

“What if we go another day? Like, why do we have to go anyway?”

“Dalitso?”

“Okay, what should we do then?”

“I’ll lift you.”

“What?”

“If I can lift you then we have to go.”

Dalitso starts to ponder again but I can’t take another round of his thoughts. “Dali, we need to go. Come, let’s finish this now.” He yields.

I step behind him and lock my arms around his belly. He starts laughing the instant I squeeze. It takes a couple of attempts with me grunting and him roaring and elbowing me in protest. Dali’s mother shouts above the commotion, “Hey, Jayi! What’s going on there? No fighting, you hear me? Is that you, Gerry?” We untangle and straighten our clothes.

“What are you doing here anyway? Go and play somewhere.”

I look at Dalitso in victory. He accepts defeat. We pull up our bikes and head out towards the gate.

“Who is Jayi?”

“Heh?”

“Your mother called you “Jayi”.”

He smiles and glances at the back garden.

“She calls me that sometimes. It’s my grandpa’s name. He’s called vaJairos. That’s why I call him Sekuru Jairos”

“Oh, okay. So, it’s like your second name?”

“Yeah, that’s why I must sit with him in the afternoon. He tells me stories about lots of things.”

“Like fairy tales?”

“Not really. Well, sometimes. But mostly stories about where he grew up and stuff. He said that he walked all the 13way from Malawi for days and days and he just followed the railway line all the way here.”

“Where is Malawi?”

“It’s a country far from here.”

“Oh, okay.”

“And then he tells me all this stuff about being nice to other people and respecting other people and saying ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ and that I must ‘remember where I’m from’.”

“Is that why you wanted us to go and sit with him? To hear stories?”

“Don’t be mean, Gerry.”

“Fine, fine. I’m sorry, big guy.”

“Yeah, but it’s okay I guess. Grandpa is funny. You should see how weird he starts sounding when he talks about the train. He talks about it like it’s a scary monster or something. Mom says it’s because he saw too many things on that long journey as he walked down here.”

“Wait, are you afraid of the railway line? Is that why you’re acting weird?”

“Me? No, of course I’m not afraid of anything.”

Dalitso fumbles with the latch, finally closes the gate behind us and we take off towards the shops.

***

Harare. The train driver makes it to the station in the city just in time to clock in but he needn’t have bothered. The departure has been delayed and the signal technicians are standing around perplexed.

“This has never happened before. It’s just not working. We are not sure what’s going on. We have tried everything, even shutting down the whole system and then switching it back on again.”

The driver finds a bench in a corner to snooze while they figure it out. His chest has a burning spot that he tries to soothe by taking slow careful breaths but every minute or so 14he lets out a volley of whinnying coughs.6 When he tries to lie prostrate on the bench, his insides at first rebel against the motion then impale him into the wood. A boozy highlight reel from the previous night flashes in and out of his mind. What was her name? Peggy? Patience? Petronella?

***

We pass by Takunda’s dad’s bakery to pick him up. He launches into us. “You guys should have been here ages ago. Where were you? I’ve been waiting and waiting.” Dalitso and I just exchange glances. We know he will calm down as soon as he is done acting like a little power-drunk bully. I ring my bell and look to the side but keep Takunda in the corner of my eye so I can see his reaction. He mumbles something about his bell not working and how his dad can fix it but he’s getting him a new one instead. Takunda is so easy to work up, if you know how. He’s in a new red Spiderman T-Shirt, same as mine. I got mine first, naturally. Our cycles are the same colour, red, because everyone knows red bikes go faster than blue ones. I have a Raleigh that you can fold in the centre, which is cool. Takunda has a Raleigh too but his bike is a Chopper with the long handlebars and a 3-speed gear. It’s not that I don’t like Choppers but that long seat is just weird. Also, who puts a small front wheel and big back wheel on the same bike? When we eventually set off, after Takunda is done being angry, we pass a couple of kids from our school and he changes down his gears for no reason. Such a show-off. He thinks his bike is faster because of the little gear thing but we’ll see. Mine has a louder bell and it works. 15

***

Back at Harare station, the switchboard lights up and the signals are working again. The driver rouses from his dreamless sleep feeling as if a steam train is charging around in his head. When he gets up, his insides stay behind on the bench while he staggers onto his feet, and when they then come up into his belly, they swim up into his throat. He heaves painfully, then wipes his mouth with his sleeves. He has had rough mornings before but this one is laced with trepidation. He could still get this day off as sick leave but he also knows that he is walking a tightrope with all his drunken missed days. He shrugs and heads to the platform boards. He needs no prompting from the station manager, knowing he has to make up for lost time. He pulls out of the yard and accelerates out of the city, sliding out with well-practiced mechanical motions. He has done this routine so many times that the responses are automatic: he flips switches, turns knobs and pulls levers in a daze. He usually blows the horn when passing Chenga Ose. It is his good-luck ritual. A part of him wishes his neighbours knew it was him driving the engine. Indeed, he has told people often about his important position, bragged while drunk.

This morning a fog hangs over Chenga Ose. A fog unlike any he has seen at this time of the year. The white orb appears as an opaque wall across the tracks and extends into nothingness in each direction. The engine ploughs into it. A chill passes through him and brings on another volley of coughs and sneezes. The locomotive is going at full tilt and blows through the white blanket, the wagons rattling at pace. A sense of dread washes over him as he takes measured breaths to calm himself down.

The train emerges from the fog and a pastoral landscape opens out with the city behind him. The train’s contact to the electric line above the train sings out and the contact of the wheels on the rails responds. The trucks rattle on as the train sweeps into wide curves and down through gently sloping 16valleys. It cuts through the hillside along a dyke and the red banks of earth zip by in a blur. On the other side, a cluster of shops, a crossing, fields and fields of some crops too young and low-growing to recognise, another cluster of shops, and beyond the fields, a weir that strains to contain a river whose pent-up waters are eager for a signal to erupt.

If the driver were to observe these hills that he has passed mindlessly on numerous trips, he would count seven. Seven hills that the ancients may have considered sacred. If he were to hear the voices echoing around the granite boulders, what would he hear? Pleas from those who came before, not to blast away the hillsides? Not to alter the configuration of this granite amphitheatre which lends an elegiac acoustic quality to the rainmaking ululations of old women who brew millet beer? Are these not the hills of Bangidza, the first hills of the first people? Would the voices of the ancients ask the driver what is a road or a railway, and what mighty gods do they serve who demand that they shift mountains and dry rivers? They would certainly insist that he look more closely at the fields and see the morning sun gleaming on the sweaty backs of farm workers whose fathers and mothers followed these same tracks to break their backs in these fields. They would ask the driver, “Who dares to own land?” The ancients would want to know if those who cleared this land knew that they were cutting down rain-making trees. It is as if they knew that tobacco would take and take from the soil, depleting it of nutrients. As if the interlopers and forgetful youth did not care to know that the people of the soil embedded the fertile umbilical cords of generations before and generations to come, in the same earth. The ancestors would warn that to leach goodness from the earth is to starve the people of the soil. They would advise them not to take as if this land never had those who lived upon it and with it, those whom they exiled from it and who now live it in their dreams. Those who came before would demand that these hills be protected from quarry excavators and mining shafts in which cages and pulleys are worn and strained to the limit. If only the train 17driver would prise open his heavy eyelids and see these bal-an-cing granite boulders used by the ancestors as granaries, burial sites and worship sites. They would show him these forgotten battlefields, sites of ambush and the desecration and betrayal of a people. Then, he would feel the ground shake, ever so slightly, as the train thundered across rivers that had been cut off and around valleys that had been flooded. If only he would see that our people now fish and hunt under cover of darkness. If he were to listen, allowing the ancestors to bite his ear, he would feel each sideways shake of the carriages as the spirits in the hills leaned into the train.

Alas, the train attains top speed and locks in. The driver sounds his horn and conquest reverberates through the hills. The train swerves again and thunders on, fortissimo, unstoppable.

***

Miner’s Drift. On our bicycles we speed along a wide footpath until we join the road heading into the township. Takunda and I pedal ourselves ragged trying to get ahead of one another to maintain front position. We get to the slight incline that leads up to the railway crossing, riding abreast and pumping furiously. Dalitso keeps up effortlessly, uninterested in our competition.

“Stop, the boom is coming down.” Takunda focuses ahead while riding on.

“You first.”

“Look Takunda, the lights are flashing!”

“I don’t care. You must stop.”

“No, you. I said it first,” I counter.

“Doesn’t matter. I’m in front.”

“No, I am.”

“No, I am.”

“No, I am.”

***

18The train begins the long sweeping arc over a ridge and into Miner’s Drift. Dotted along the ridge are the verticals of mining scaffolding and pulleys. The town itself is not visible yet, save for grain silos and a couple of communication towers. The train driver looks at his watch and sees that he has made up for the lost time. He takes a deep breath and swallows to ease his throat. His tongue catches on the roof of his mouth. He looks around for the bottle of water he knows is somewhere in the cab. The headache is now at full steam and he feels hot, feverish, his insides begin their revolt again. The sideways rocking and jolting of the train has had him fighting off nausea for a while. He looks ahead and sees that he has turned into the final straight entering the town. Ahead, he can see flashing lights at the crossing and the booms coming down. He sounds the horn, then turns back and resumes his search for the fallen water bottle.

***

The train horn blasts into my ears.

I start pumping my brakes while keeping my eyes on the train. Takunda’s foot misses a pedal; he cuts across me and jams our front wheels. We both land in the red dust. Dalitso comes crashing into us. I push him off me, but I push too hard and my shove lands him in the path of the train.

***

The driver sees the water bottle rolling under his seat and reaches for it, crouching low. Shakes his head and struggles back onto his feet. He unscrews the cap and takes a few painful swallows. The hot reflux remains lodged in his tract. A mouthful of water only nudges it down a notch.

The tracks in front of him, at the crossing point.

Something there that shouldn’t be. White blanket. No, not déjà vu. Small this time. He sees a little kid in white garments scrambling up onto his feet, right there on the rails. 19

Not possible. But yes, there is someone, there is this fucking kid. The ball of acid stops in his tract. He just stares as it happens. The acid burns. Paralyzed to the spot. Why does he not move? The corrosive burn radiates outwards into his chest and belly, rises back up his throat. What is he doing on the tracks? Why this, why now? His stomach lurches and caustic bile shoots back out of his mouth. No, he thinks, no, not this. Shaken, unsteady, light dimming, he lunges for the brakes.

***

Trains blew past him, Sekuru Jairos, at intervals as he walked. He travelled alone but knew he was part of a long human chain seeking their fortune southwards. There was evidence of those who were travelling ahead of him. Remnants of a fire here. Tall grasses flattened out as a temporary bed. Empty cigarette packets, matchboxes, corned beef tins, rotting flesh picked at by crows and vultures, a mound of earth the length of a grown man, with stones laid over it and stuck in at the head a crude cross made from branches and tree bark. Sometimes he passed groups of men working shirtless to repair the rails, shivering with fever and sweating with exhaustion, replacing timber on the tracks, laying new lines at a mile each day for trains they would never ride.

Sekuru Jairos swore at each train as it blew past. A great beast snorting clouds of black dust and sparks of fire, with red eyes, a shrill bellow, a charging animal with insatiable hunger, gasping and heaving forward, grinding its jaws. He spat on the railway tracks and cursed them as he set off each morning. Swore he never wanted to see another train ever in his life, if he only made it to Salisbury, and if anyone ever made him look at one again, he would never let them rest.

***

High in the skies, a line of storks breaks formation and scatters. One spirals downwards in broken flight. 20

A small thud of noise, insignificant, no louder than the odd calf struck down on the tracks.

Somewhere near the boy sprawled in the dust, another boy is screaming, hands covering his eyes. What cannot be unseen.

The bird impacts the ground in a soundless burst of white feathers.

***

Up on the ridge, the earth is trembling: shaft cables snap in quick succession, sending loose cages crashing down into the depths.

Streams in surrounding farms break through weirs and cascade downstream in cathartic waves of release.

Below Pfumojena township, at the pool in the stream, bubbles rise from the depths and sigh into the surface air. Reeds tremble in waves radiating outwards from the pool, sending weaver birds into upward surges of panicked flight.

***

I lie in the dust looking around me. The top of the rail is smooth and shiny. The sides are caked in dull soot blending in with the dirty quarry stones and wooden sleepers. The smell of the hot tarred road at midday, oil, steel and red clay soil fills my nostrils. I sit up and stare. At the tracks, at the pair of feet and white garment. The train blows past with a sound like a rounders bat swinging into a small bean bag. Like a bag of flour landing on the floor in a puff of white.

Then train brakes start screeching and the horn blasts long and hard. The trucks speed past and mesmerise me. The horn trails off and a high-pitched whine rises louder and louder. I have energy rising within me, singing in my veins and making my limbs tingle. All I can see is what is directly in front of me. Inside my head blankness, that is all I know. Time slows down and then stops. The whining recedes. It’s 21all too quiet now. The sky closes in on me. All around me the world darkens.

The figure in white reappears but it is now Sekuru Jairos sitting on the tracks in his armchair, staring at me. I squeeze my eyes shut. When I peek through them again, it is now Dalitso. My heart leaps into my throat and thumps at my epiglottis. I squeeze my eyes shut again. I do not know for how long. I want to keep them shut forever.

Slowly, I reopen them. It is Sekuru Jairos again, and he stands up, eyes boring into me and points at me. Silently, he mouths,

“You. You. You.”

His voice loops in my head, over and over. Then he fades away.

The sky rifts apart and light filters back in, widening my field of vision. A heavy molten light that leans on me. The surge of energy abates and seeps out of me. My limbs weaken under the weight of the sky.

The train has come to a standstill further down the track. A man, bent double, vomits beside the engine. Running feet come closer. Distant scream after distant scream floats in from above and across the tracks. Silence again.

The world has cracked open.

Then someone places a hand on my shoulder and shakes me, hard. I can see what they are doing even though I cannot feel it. My teeth are grinding back and forth, molar on molar, bone on bone, and I can’t hear what they are saying. The whining sound pierces my hearing again but not as loud as before. Overhead, the noon sun blinds me like the township tower lights in the evenings, sunspots floating black and giddy.

I squeeze my eyes tight closed and scream into the dust. I feel the raw strain in my throat but I do not hear my voice.

***

Dalitso is gone.

2 The fall of Portuguese East Africa in 1974 brought a wave of exiles across the border. Some dropped off the caravan here in Miner’s Drift and others carried on to Harare and some over the other border into South Africa. The salty colonial Portuguese who couldn’t lord it over there, as independence became inevitable, settled here and opened little businesses and created absurd little micro-fiefdoms. The mindfuck is how, when MNR/RENAMO started shooting up the new Frelimo-led Mozambican state, newly independent Mozambicans streamed back across the border and next thing you know they are now interpreters under their former colonisers yet again, in these little fiefdoms. Comrade Samora Machel must have let out a big, “What the actual fuck?” up there in Maputo. It is what it is, I guess.

3 The little town has long been a place of migrants. Mostly, the Chewa, Nyanja and Vemba from the north, seeking refuge. A tough home for those who never leave. But also a home for those who leave the small town itself to seek fortune in the cities and lands abroad, become exiles themselves, only to come back where their souls never left. My younger self couldn’t wait to get going.

4 Pfumojena, Mashayamombe and Nehanda townships, created as war-time confinement camps referred to officially as “Protected Villages” and more appropriately as “Keeps” by the people who were forced into them during the time when “this country was beautiful,” were named after vanquished African spiritual mediums, military heroes and legends.

5 Between 1965-1980 the UDI Rhodesian Front regime of Ian Smith was under international sanctions which the French decided to ignore. And so at the turn of independence, Peugeot, Renault and Citroen vehicles were ubiquitous on Zimbabwean roads.

6 “Long Illness” is what they said in the papers and in the news, back in the days when AIDS-related deaths were newsworthy and still a devilish phenomenon mentioned in hush-hush tones. Euphemisms that mask our fears. The tuberculosis, cholera and typhoid, malnutrition, kidney failure from the backbreaking work in the mines and fields, all naughty descendants of the ancestral poxes that drifted in on those colonial wagons.

3

Fight or Flight? 1988

Listen, this isn’t the worst day this week. I’m standing-standing at the gate and waiting to see if Sisi Natsai has brought me anything from town. I’m always the one she talks to as soon as she gets home, calls me to sit down on her bed. She sits across from me massaging her ankle with those three thin lines still visible.

“Sisi Natsai, am I also touched by the njuzu?”

“Why do you ask that?”

“Because I’m always doing bad things and Mai is always angry at me.”

“What bad things are you talking about, kid?”

“Like that bad thing that happened at the railway. Maybe that’s why Mai is always hitting me?”

“You must forget about that, Gerry, you hear me?”

“But what if everything happens to me because I’m also touched and I don’t know it?”

“Gerry, look at me.”

She sighs.

“You’ve done nothing wrong, okay? No-one, nothing touched you. Don’t worry about all that for now.”

“But I don’t understand why…”

“Shhh kid. You’ll understand when you’re older. Trust me.”

“When, Sisi Natsai, when will I be older?” 23

“Soon. Then I’ll explain everything to you, I promise.”

“Should I also pray about it like Mai does? Mai says prayers answer everything. Even when she’s hitting me.”

“You can pray if you want to, little brother.”

“Do you pray, Sisi Natsai? How come I’ve never seen you praying.”

“Oh Gerry, add that to the list of things I’ll explain to you when you’re older.”

***

Stay with me, time is passing. Today I’m in the lounge, sitting in Father’s chair while watching The Mukadota Family on TV. Mai Rwizi is chasing Baba Rwizi, aka Mukadota, around the sofa in their one-room house because she has caught him entertaining his mistress, Machipisa.7 In real life, Mother comes back home from another day of work in the Girl Child Department of The Ministry and is instantly on me like dust on Vaselined legs.

She is forever threatening to sell me to the Gule dancers from Pfumojena township if she ever returns home and finds her vegetable garden unwatered. On this day, even though I haven’t sprayed a single drop of water on her garden, she has a hunch that I have been selling some of her tomatoes in the neighbourhood, and therefore she is in a temper. She can’t prove her hunch and I deny it vehemently so she mumbles, “You will not see heaven if you carry on like this,” and then walks past me into her bedroom.

At some point though she has a stroke of genius, decides she’s being too soft and sweeps back into the lounge with a slim black belt in her hand. It has occurred to her that the dusty kid sitting on her sofa watching TV, with the crocheted sofa covers scrunched up and swallowed by the cushions, 24deserves some correction. She slides some rhythm into the belt strokes.

“I-told-you-not-to-watch-TV-until-you-have-bathed.”

The strokes ring out sharp and land with a sting that feels like a surface pinch at first, but then slowly the sharp strokes pierce into flesh and flick pins into my bones.

At whipping time Mother grows an extra arm. There is always one arm coming down as another cranks up. She has me pinned. Braving it, I squirm headfirst between her legs and briefly get my face caught in pleated waves of georgette. Trapped and squirming. She lands a few quality strokes.

To escape these assaults on my person, I usually run into my bedroom and wedge myself against the door but on this day, I turn left out of the lounge and head out the front door.

The taste of freedom.

I carry on into the dimly lit driveway. Somewhere between the front door and the gate I decide I’ve had enough of this home life and look around for my dog Spider.8 At some point in a ten-year-old boy’s life, he comes to a fork in the road. Life is a series of decisions and mine have escalated. Left or right? If I’m going to run away, then I need a companion. No point in running away if you can’t do it properly and if you don’t have a Mudhara Bonnie to your Mukadota.

It’s now dark outside and I can’t see the branches of the guava and mango trees in the front yard. For a few moments I pause to catch my breath in the shadow of the trees. Trees are a shelter for me, a safe place to hide out. In my haste to get away from my mother and the belt, I rushed out of the house empty-handed. Now I’ve decided to run away from home and haven’t packed anything to take with me into exile. Shirtless, panting, unshod and face still wet, hot and salty, I stand at the gate waiting for Spider. He will be at the rear of 25the house at this time – hanging outside the kitchen door listening to the clatter of pots and waiting for an edible scrap to fly out the door. There is no discipline to Spider’s begging. No decorum. Depending on how rough his day at the office has been, evidence of which would be holes dug all around the garden, he will either be staring animatedly at the door or scratching furiously at it. Waiting at the gate, I start to realize that my journey into the great unknown might have to be a solo effort.

The warm darkness within the yard is comforting for me. I don’t need light. I would know my way around every ridge, rockery, tree and flower bed with my eyes closed and walking on my hands.

There is a faint glow of moonlight but the clouds hold steady and it stays hidden. The darkness outside the gate though is a whole different proposition. Peggy, the town ghost, tends to lurk on the highway, a kilometre or so away, and there are streets and houses and the shops in between but I’m not taking any chances. The sounds of rainwater dripping from leaves overhead and the smell of hot soaked earth mingle in the evening air. Everything is quieter, only the muffled noise from a neighbour’s TV and distant traffic reach my ears. My whistle doesn’t get past the lump in my throat. In between sobs, receding heaves and anger, my mouth is not whistling. That whistle can get my hound here in an instant. I developed it to sound like his name; a feat which makes me proud. My pride in this though has been dented because Spider also responds to any old whistle from any old mouth. His is a politics of the stomach. His loyalties lie with whoever fills his bowl.

I hear the scurrying of Spider’s paws in the darkness. He is on me before I can raise my arms against him. Face licked, chest wildly scratched and deep breaths taken, I unlatch the gate and he races out past me. It’s a significant moment, I tell myself: I take one last look back at the house I have grown up in. I have had so many happy moments here. My first words and my first baby steps towards Natsai, both of which I’m 26certain were spectacular triumphs. So many birthday parties, learning how to ride a bike and receiving Spider from Father on my eighth birthday – but now it’s time to go.

Spider is a shaggy, fawn-coloured, gangly contraption with sparkling grey marbles for eyes and two rows of magnificent teeth which he employs on all occasions. He bites to greet, tease, eat and play. Good old Spider – my brother from another species – with a name from yet another species.

I turn away with a heavy heart, latch the gate and set off down the road. A cool damp breeze blows to remind me of my inadequate clothing. Various enticing odours – meat stew, tripe, fried eggs – from cooked suppers are drifting across the street, clashing in my nostrils, and threatening to jeopardise my expedition. To miss out on supper is a challenge.

Street lights have come on. They always come on in the same sequence. Pop, pop, pop. There is a curve in the street out to the right and they shoot round that bend and up to our house in rapid succession. I always pretend I can outrun them. As things stand, I will never see these lights come on again. Never again shall I stand outside by the gate with Spider panting by my side, eager to be let out, ignoring Mother’s shouts and threats of violence, contemplating how many eggs and pints of milk I would need to eat daily to get fast enough to outrun the Despondency Avenue street lights.

Spider comes to a halt and waits in the road a few metres from me in the amber glow. He has enough empathy to allow his travelling companion to wrest free of his attachment to his former home. I continue down the road and he capers a few steps ahead of me. We walk two houses down to the corner of the street and I feel this is far enough. We shall set up our living arrangements here under the corner streetlight, far from the woman in that house and the haunting memories that hopefully will fade over time.

And so, I stand under the streetlight surveying my new lodgings and trying to mark out a boundary fence with a fallen twig. This is going to be good fun. The sensation of freedom and adventure is throbbing in my scrawny chest, 27drying my face and making my fingers itch. The latter may be a bout of hives. All my Boy Scout skills are going to come in handy: I can now knot a bowline-on-the-bight and am working my way towards my first compound knot. I have also been for two hikes and two overnight camps.

It is dark though. I peer around the corner and Alarm Street is lit in most parts but also has tree branches and foliage blocking out the streetlights in some parts and throwing down holes of darkness. No fear here. Spider is having a good time prancing around the corner, disappearing into the dark spots and then jumping back into the light with his mouth ajar and tongue flapping around. Being outside the gate is a rare treat. The only time he gets to play outside is when my old man comes back and he bolts out the gate soon as it is opened. He streaks one way down the road barking at the neighbours’ dogs and then streaks back down the other way fleeing from his shadow.

Another wave of cooked supper drifts in, this time from the neighbours across the road who always cook nice food. I almost befriended their son Forget a few months ago and tried to visit him at mealtimes but their maid kept telling me he wasn’t in even when I could see him opening and closing his mouth through the lace curtains in their dining room. Grilled sausage comes riding in on this new wave of cooking odours: my stomach rumbles a bit and nudges my face in the direction of my former home. I take the quickest glance backwards and then focus on my new residence.

Spider starts barking wildly and leaping into the air and snapping at something. It’s a flying termite. The mutt is insane. The first insects of the rainy season are coming out of the termite hill across the road and flying towards the streetlight.

Spider goes delirious. He leaps into the air and clamps his jaws over one, promptly spits it out when it flutters on his tongue. These are the larger flying termites. A flurry of them drift into the light and start circling around the lamp post and up towards the bulb. A squadron comes in and the fluttering sounds turn into white noise. Spider stiffens and 28