7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

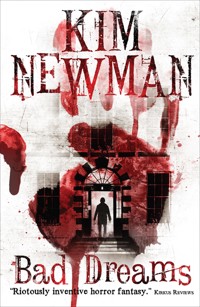

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

When Anne Nielson, an American journalist, travels to London to investigate the death of her sister Judi, she finds herself sucked into her nightmarish world of corruption and perversion, populated by dealers, pimps, sadomasochists and a vampire race that feasts on their victims' dreams. At the centre of this sickly web lurks the Games Master. Something more and something less than a man, the closer Anne draws to his domain the more she endangers herself and everyone she knows, and soon she will learn that the Games Master is not just a name, and when he plays, he plays for keeps. An updated edition of the critically acclaimed novel, featuring the short story 'Orgy of the Blood Parasites' and a brand-new afterword by Kim Newman.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Kim Newman

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

The Morning Before

1

2

Daytime

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Evening

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Entre’acte

1

2

3

Night

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

Dawn

Bloody Students

Prologue: Lunacy in the Age of Reason

Part One: Out of the Animal Room

Part Two: The Freak-Outs

Part Three: Graduation

Epilogue: Reason in the Age of Lunacy

Afterword

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

ALSO BY KIM NEWMAN AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Anno DraculaAnno Dracula: The Bloody Red BaronAnno Dracula: Dracula Cha Cha ChaAnno Dracula: Johnny Alucard

Professor Moriarty: the Hound of the D’UrbervillesJagoThe QuorumLife’s LotteryAn English Ghost Story

COMING SOONThe Night Mayor

Bad DreamsPrint edition ISBN: 9781781165614E-book edition ISBN: 9781781165621

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: November 2014

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Kim Newman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 1990, 2014 by Kim Newman. All rights reserved.

‘Bloody Students’ also previously published as ‘Orgy of the Bloody Parasites’.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive off ers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

For The Peace and Love Corporation, Plc.

‘First you dream, then you die.’

CORNELL WOOLRICH

THE MORNING BEFORE

1

Judi dreamed she was waking up. Without moving, she got out of the double bed, pulled a rough towel robe over the things she was still wearing, and searched the mess on the carpeted floor for her Camels. She found most of her clothes, relatively unspoiled, mixed up with Coral’s. Also three empty Dom Pérignon bottles, a shredded Iris Murdoch paperback, some studded leather fripperies and a multi-coloured scattering of pills. Her head was an open wound, leaking steadily, and she had either vomited recently or would do so soon. She hauled her heavy black jacket out of the heap and patted its zippered pockets. No luck. She walked across the room, knees and ankles threatening to fail her, and became acutely aware of the sticky ache between her legs.

Sweet Jesus, did we get raped again?

Most of one wall was mirrored. On this side only, of course. The room beyond was dark. Even if she put her face close to the glass she couldn’t see through. It was probably empty this early in the morning. The show was over. She sat at the dressing table and scratched her scalp. The spiky perm was well into its decay. She pulled her handbag open and went through it. The Camels were there, but someone had snapped her disposable lighter in half.

Her money, credit cards, diary, hankies and address book were soaked. She stuck the least wet cigarette in her mouth, hoping she would not burn half her face off.

No matches. She would have to wake Coral.

The other girl was still in bed, comatose. She had been twisting and turning as if buried alive. A nylon sheet wound around her like a soiled blue boa constrictor. The bare mattress was missing several buttons, and patterned with old pee, blood and come stains. In the bruising on Coral’s back, bottom and legs, Judi could see designs. The yellow and blue smudges were handsome faces with red welts for eyes. The faces coalesced, making a Japanese dragon with heaving shoulderblades for wings and penny-sized scales of ragged flesh.

The little green scorpion tattooed on Coral’s wrist scuttled out from under her digital watch and took refuge in her armpit. Judi was back in the bed now, sinking into the mattress, soothing the ruffled dragon with practised massage. She had given up on Coral’s matches, and spat the Camel out onto the pillow. The bed hugged her. The duvet slithered up over her bare legs. Judi’s eyes turned inward, focusing on a white hot point three inches behind the bridge of her nose. The pain went away.

She was not dreaming she was awake any more. She opened her eyes and saw the skylight. The dingy grey looked about ready to fall. She had always thought Chicken Licken had a better grasp of cosmology than Galileo.

Really awake, she sat up in bed, wearily ready to go through it all again.

That was when she realized she was handcuffed to a severed arm.

2

The old, old man watched, his own reflection faintly superimposed on the dusty one-way glass. In his current condition, he was glad not to be looking at the silvered side of the mirror. He had lost a lot of weight recently. He did not like to be reminded of his flesh. It was turning into greasy lumps that shifted and shrank beneath his slackening skin. The fabric of his quilted dressing gown hung heavily on his arm as he raised a hand to the cold glass. His fingers were dead, the knuckles swollen with ersatz arthritis.

He was unaroused by the spectacle. Judi was thrashing around the room, unsuccessfully trying to rid herself of the dead weight hanging from her wrist. She was screaming, but he had chosen to switch off the intercom. He could still just hear the racket, but these Victorian walls had been built for privacy. Already, the girl was beginning to wear herself down. Already, he was beginning to feel the warmth.

He knew his face was filling out, settling comfortably again onto his skull. His hands grew fatter. The skin crept back over the half-moons of his fingernails. His fingers bent, knuckles cracking, he made a comfortable vice-grip fist. He felt himself expanding to fit his clothes. His dry mouth filled again with water. His teeth swelled, and sharpened, changing the shape of his jaw, making him grin.

Now, he was ready for Judi.

He used the connecting door. It had never been locked, but there was no handle on her side. Judi had finished with her hysterics, and was back in the bed. She was coiled in a foetal ball, with Coral’s arm sticking out in place of an umbilical cord. The little green scorpion was resting. It had been neatly done. There was almost no blood. The room smelled musty. He caught the residues of spent lusts in his nostrils, and drew them into himself, tasting them as they went down.

The things he had watched last night were replayed inside his head. He smiled, new skin tight over his cheekbones. Judi, he remembered. And Coral. The clients. Pain and pleasure, locked together. And the almost pathetic pettiness of it all. It had barely been an appetizer for what he would do now. Coral, a pretty but dull girl, would have been a less substantial delight than Judi. Barely a morsel. But still, it was a shame she had been wasted. Her death had given him little sustenance.

He climbed into bed and cuddled Judi. He touched her fractured mind, feeling for the spots that would give first, sinking black fingers into her confusion. She was delicious. He stroked her side, his nails turned to bony scalpels. He opened her at the hip, and scraped the bone. She convulsed like an electroshock patient. He clamped a passionless kiss over her shriek. He swallowed air, and her cries echoed inside, him.

He fed off her for hours, until her heart burst.

DAYTIME

1

Anne was waiting for The Call.

Every couple of days, she would telephone the old family home, and talk with Dad’s nurse. She had never met the woman, and at the echoing end of the transatlantic line, she sounded like a little girl a long way away. Her father had had his second stroke back in September, and all the doctors were expecting the third soon. If not before the end of the year, then early in January. The first stroke, three years earlier, had just slowed him down and slurred his words. The second had put him in a chair and made talking a supreme effort. The third would kill him.

She had the Radio 4 early morning current affairs show on in the tiny kitchen, and the Channel 4 breakfast television service on in her front room, and was dividing her attention between them, following several stories as they broke. It was mostly international activity, in Central America and Eastern Europe, but there were a few local, London-based, items she was keeping an ear to. She had already done her two days in the newsroom this week, but she was scheduled to turn in a couple of pieces by Friday, to meet the deadline for the Christmas double issue. The Aziz inquest would be turning in a verdict in the next few days, and, depending on the degree of officially admitted police involvement in the youth’s death, that would affect the conclusions she would draw in the last of her articles on racist attacks.

The old boiler rattled, and Anne checked the heating. The flame was going full inside, but the flat was not getting any warmer. She really ought to start looking for a new place in the New Year. When her father died, there would be some money from the estate. She shivered with the thought, and tried to unthink it, forcing it back into the blacks of her mind. She shivered again, only with the cold, and pulled her robe tighter over her nightie. It would be warmer when she had her clothes on.

There were tanks moving through rubble-strewn streets on television, and a foreign correspondent on the radio was making a report with the whoosh of anti-tank rockets in the background. Anne was not sure whether the coverages were of the same crisis. Usually, news wound down for Christmas; this year, events were speeding up as the holiday approached. Some governments were probably planning to spring nasty surprises over the Christmas break, purely to avoid publicity. TV programmers had already overloaded the airwaves with blockbuster movies, light entertainment specials and quiz-of-the-year features, and there was no room at the inn for states of emergency, covert activities or the odd execution.

She had a morning at home due, and the notes for her pieces were neatly piled by the word processor in the front room. That meant, since she did not have to struggle through the rush hour to get to Clerkenwell, she could take some care over breakfast. ‘The most important meal of the day,’ her British friends would tell her as her stomach somersaulted at the sight of grease-grilled bacon, runny eggs and a horror they called fried bread. In the kitchen, a cheerful vicar on ‘Thought for the Day’ was trying to draw some Biblical parallel between current events and those in Nazareth at the time of the Nativity. While her old-fashioned percolator dripped thick coffee, she mixed St Michael’s ‘Thick and Creamy’ strawberry and mango yoghurt with Neal’s Yard muesli, and added just a little milk. Two croissants were gently warming in the depths of the oven.

At eight o’clock, the radio and the TV hit news bulletins at the same time, and told the same stories in slightly varying ways. Anne did the remains of last night’s washing-up. Two teacups, two wine-glasses, and the dug-out-from-somewhere ashtray. For a moment, she wondered if Mark had expected to stay the night with her. She thought that was not going to happen, but recently, he had been a bit broody around her at the office. He went all quiet and British when she was talking to anyone else, and was hearty with her in that slightly hollow way of his. She put the dripping cups and glasses up on the rack to dry. She was getting the impression that Mark was capable of a species of desperate devotion she would find stifling. For her, this year, turning thirty without having been married or had children had not been the stereotypical shock. The only thing she wished she had done was write a book, and there was plenty of time for that. Maybe she could fix up the racist attack series. It was an important subject.

She took the croissants out, welcoming the outrush of warm air from the oven. Outside the fire escape window, she could see frost-furred ironwork. It was cold, and the forecasters were saying it would get colder. She carried her breakfast tray through to the front room. The television was warning of a traffic snarl-up in North London. The trains were running intermittently because of the cold. Every year, winter caught London Regional Transport by surprise, as if they expected a dingy summer to stretch on until the year’s end. Anne’s fingers felt the chill, and she warmed them on the croissants. Sitting at the folding table she had pulled out for Mark and not put away, she ate the croissants and watched the television.

Usually, with her breakfast, she opened her mail and set aside letters that needed immediate replies, listed cheques in her account books and paid bills. She liked to get that out of the way before she started anything. Her father’s lawyers were sending her a packet of legal documents federal express. But, thanks to the Christmas post, the mail was not arriving until late in the morning this week. She already had too many cards for her limited mantelpiece and shelf space, and was beginning to regret her decision not to bother this year. She took her first caffeine hit of the day, and considered the muesli and yoghurt.

At first, the expectation of The Call had been constant. Every time she heard a telephone ring, even if she was not in her flat or an office where she could be traced, she had been instantly certain that this was it, and felt her heart squeeze. Then, the dread had turned to a dull resignation, although she realized that, when it came, it would still surprise her.

Fathers died, she knew. Hers had written an entire play about the fact. And when the third seizure came, the film of the play would undoubtedly be pulled out of the vaults and shown on late-night television as a tribute. She had videoed On the Graveyard Shift at Sam’s Bar-B-Q and Grill the last time it was on, but had not got around to watching it again. Produced on Broadway in 1954 and filmed in 1955, the property had been cited by the Nobel Prize Committee as a great achievement, but it had also dwarfed everything else Cameron Nielson ever did, including raise children. Anne still found it hard to associate the play, written before she was born, with the distant, kindly, disappointed man she had known all her life. In the big, last-act speech, where Maish Johnson – the role that proved Brando’s Stanley Kowalski was not a one-off achievement – angrily expressed his grief at the death of Sam, the fatherly-wise owner of the all-night Bar-B-Q and Grill, and denounced everyone else’s numbed reaction to the bad news, Anne knew that her father had written the cornerstone of his own obituary. He had been a young man when he wrote Maish’s speech, fiercely identifying with his hero; how would he feel now that he had been pushed, presumably kicking and screaming inside his chairbound bone-and-flesh prison, into the Lee J. Cobb role of Sam?

She took a spoon to the muesli and yoghurt, and mixed them up more thoroughly. The news was starting to repeat, so she zapped from channel to channel, getting an early morning educational show about claw-feed grinding, a high-tech commercial for a bank, and three presenters on a pastel couch swapping mild innuendoes with a teenage pop star. The coffee was getting into her system, waking her up. She laced her cold fingers, and rubbed her palms together, generating some warmth. Back at the news, there was a thirty second blip on the Aziz incident: a black and white photograph, grainily enlarged, of the smiling Pakistani at his wedding; another, post-mortem, of his swollen face on a pillow; a brief, live, snippet of Constable Erskine, in uniform, being hustled out of the inquest, dodging microphones.

At the sight of Erskine’s face, Anne felt a flash of cold anger. She had never met the policeman, but she had read the doctor’s reports on Charlie Aziz, arrested for ‘driving without due care and attention’, breathalysed and proved not under the influence of alcohol, then battered to death by ‘person or persons unknown’ in a South London cell. The official version was that Charlie suffered a claustrophobic spell and injured himself fatally, but Anne knew that was not consistent with his all-round injuries and with the police force’s unexplained suspension of Erskine, the arresting officer. Erskine, a blandly handsome young man, did not look like a monster, but then they never did. In his off hours, according to Anne’s investigation, Erskine was a member of the English Liberation Front, a far right splinter group who alleged that immigrants from the Indian sub-continent and the Caribbean constitute an army of occupation and should be resisted with maquis tactics.

Aziz’s parents were glimpsed, but they did not get to say anything. Over the last few weeks, attending meetings of the Charlie Aziz Memorial Committee to Stop the Attacks, Anne had got quite close to the boy’s mother. She admired the woman’s quiet determination, and her ability to cope with family tragedy while doing something concrete about it. Mrs Aziz, Anne believed, was quite capable of forcing answers from the police where years of investigating journalists would only get nothingy press hand-outs. And if that happened, there would definitely be a book in it. Perhaps even a television docu-drama. Perhaps…

She picked up her spoon, and the telephone rang. She dropped the spoon, and found herself shaking. It was only partly the cold. Using the remote control, she turned off the television. The ringing was needlessly loud.

Nerving herself for The Call, she picked up the telephone, and said ‘hello’.

The line did not crackle. It was not from America. This was not The Call.

‘Anne…’ It was Mark. Her whole body tensed. She did not need an ‘…about last night…’ conversation. ‘Anne, I’m ringing from the office…’

He sounded edgy, urgent, like a conspirator during a crisis.

‘Mark, I…’

‘The police have been checking up on you, Anne…’

The doorbell rang.

‘Mark, excuse me, someone at the door…’

She put the receiver down, and stabbed the entryphone buzzer. It would be the postman, and she did not want to miss him and have to take the trip to the sorting office to pick up the Federal Express packet. She unlatched her door, and stepped out onto the landing.

It was not the postman. Anne shrank back, mentally kicking herself for her lack of caution. In New York, that sort of mistake could get you killed; and London these days was not exactly a paradise of non-violence either.

‘Good morning,’ said the visitor. ‘Anne Nielson?’

It was a civil service type in a grey topcoat, but the dread did not lift.

‘Yes?’

He showed her a card, with his photograph under plastic. She looked at it, but could not focus on the words.

‘I’m Inspector Joseph Hollis, from the Holborn Police Station.’

The name did not mean anything to her. She looked backwards, at the still off-the-hook telephone. She adopted a neutral expression, and did not invite the policeman into her flat. Any business they had could be done on the landing. She was not paranoid, but she had friends who had been harassed for what they wrote. She had not expected any official feedback on her Aziz pieces, but she was not surprised.

‘Miss Nielson?’

The face was unreadable but vaguely sympathetic, the voice professionally expressionless.

She took a breath. ‘Yes.’

‘Anne Veronica Nielson?’

She expected to be told her rights. ‘Uh-huh.’

‘And do you have a sister, Judith Nielson?’

Judi! She always came out of left field, but today…

‘Yes. What is this about?’

This time, the policeman drew breath. Whatever it was, she knew, it would be bad. With Judi, it was always bad.

‘I’m sorry, miss, but I have to tell you that your sister is dead.’

2

The night before, Nina had been out with Rollo, one of her regulars. They had ended up at his maisonette in Hackney. She had tried her best, but just was not up to it. Afterwards, she had vomited biriani on his new duvet cover. It was decorated with ringlet-haired ancient Greeks kaleidoscopically demonstrating an assortment of lovemaking positions. It was supposed to be tasteful.

Rollo had kicked her off his futon and called for a minicab. He had given her less money than usual, and made her wait for the taxi outside his front door. She had got cold listening to him clatter about the house, tidying up, and had come even further down. Her toes were still frozen, without feeling, from the twenty minutes outside. She had had to pay the driver out of her earnings. Usually, Rollo would give the cabman ten pounds to cover it. He had not made a date to see her again. They had met in the first place through the ‘Heartland’ section of City Limits. He was ‘in the music business’, but did not have any records out at the moment. His sitting room was full of framed posters for concerts by bands she could barely remember.

Back in the flat, she hugged her Snoopy pyjama case, imagining a gentle and considerate lover. Someone like Jeremy Irons in Brideshead Revisited. A schoolfriend had once told her that all prostitutes were really lesbians. But, then again, Nina was not a real prostitute. She was… What was she? A party girl, she supposed. Like everyone else, she called herself a model on her tax returns.

Exhausted, she did not dream.

When she woke up, she felt ghastly. It was then that she decided to quit using smack. But smack was not ready to leave off using her.

Aware that she needed to build her strength again, she fixed up as substantial a breakfast as was possible with what she had left in the tiny fridge and the cupboard over the sink. Branflakes, six cheddar thins, grapefruit juice and a cup of jasmine tea.

She sat at the kitchen table, looking at the neatly laid breakfast for a quarter of an hour. The hot water in the teacup slowly darkened until she could no longer see the sachet in the bottom. She took the paper tab and hauled the teabag out on its length of cotton. She dangled it in front of her face, and took the soggy lump into her mouth. It was slightly scalding, but the flavour was good. She could taste the perfume.

She spat the bag out into a saucer, and began to nibble one of the biscuits. Her stomach contracted sharply. ‘Soon,’ she said, ‘it’s coming soon.’ She kept the cheesy pulp in her mouth for minutes, squeezing it through her teeth. Finally, she swallowed. It hurt going down, but it hurt a lot more coming up.

She bent double, cracking the cereal bowl with her forehead. The spasms hit her again and again in the belly. She twisted off the stool and dived for the kitchen mat, curling up around her pain. Milk and bran dried on her face. She managed to control herself before the kicking started.

This had happened before. She could live through it.

After a while, she calmed down. She unwound herself, and lay face up on the floor, looking up at the Marvel comic covers pasted to the ceiling by a previous tenant. Silver Surfer and Daredevil, Iron Man and The Avengers. She had had a guy around for a party once who was a comic collector. He claimed that, unmutilated, several of the ’60s issues that had been cut up for wallpaper were worth around fifty pounds. What a waste.

She sat up, and felt temporarily at peace with herself. It would not last. There was no smack in the place. She had hoped to be able to find the silver paper her last jab had come in, but it was lost. She had got a hit off that kind of minute residue before, by licking it. It felt like sherbert on the tongue, and a carnival in her brain. At least, it had once. More recently, she had been treading water, using the shot to stay even, not to get ahead. That was dangerous, but she was a strong person, she told herself, she could deal with it.

It took her a full minute to dial Clive’s seven figure number. Apart from her own, it was the only one she knew. She had forgotten her mother’s, and had a little book for regulars and friends.

Clive. Charming Clive. Well-spoken Clive. Cunning Clive. He was the one who had found the song with her name in it. Nina Kenyon. He had suggested she find a partner called Ina Carver. It was the first line of ‘My Darling Clementine’. Ina Carver, Nina Kenyon. Excavating for a mine. Clive would have smack. He always had smack.

Clive’s telephone rang four times, then his answering machine cut in. It told her in the kind of voice she usually only heard on University Challenge that Clive Broome was out right now and that she could leave a message after the bleeps if she wanted to. She did not.

She could not quite get her phone back on the hook. The tangled cord got in the way.

In any case, she knew Clive would only come across if she paid him for her last shot. He was her friend and he loved her, but he was a businessman like any other and he could not make that kind of exception. She barely had enough cash left over from last night to get her through the day.

Even from the other side of the room, she could hear the phone. The dialling tone buzzed, annoyingly loud, like a persistent insect.

She squandered a fifty pence coin on the electricity meter and turned the fire on full strength. Standing up, she felt pins and needles in her knees. The gilt-edged invitation that had come in yesterday’s post was on top of a pile of newspapers, magazines and bills on the coffee table. Under the copperplate request for the pleasure of her company and the address, Amelia had written ‘bring a friend’.

So, if she could get herself together, there was the prospect of earning some good money. Not in a terribly comfortable way, but good money was good money. She had been to Amelia’s ‘entertainments’ before and survived.

And Clive would be at Amelia’s ‘entertainment’. And wherever Clive went, he did business.

‘Bring a friend.’ Nina had not known if Amelia was being graciously hospitable, or issuing an order. ‘A friend’?

Nina had thought that had to mean Coral. The last time she had met Amelia, she had been with the skinny blonde in the Club Des Esseintes. The hostess could easily have been quite taken with Coral. The girl had certainly been exciting attention for as long as Nina had known her.

They had come from the same school in North London originally. At first, Nina had been the one to show Coral how to get along. They had worked as a sister act for a while, but had got on each other’s nerves. They went back too far to be comfortable together these days. Coral could be a moody cow when she wanted to, and was ungenerous with her gear. She had stopped crashing most nights on Nina’s floor a few months before, and found a place with the American girl, Judi. Once Coral moved out, Nina found she got on better with her friend. There were plenty of relationships that worked best that way.

Judi? Maybe Amelia meant Judi. Nina had introduced her to the hostess as well. The more she had thought about it yesterday, the less she had known whether to call Judi or Coral. In the end, it had hit her that she did not have to make a choice. Judi and Coral were still together, at the same address. If she phoned them, one would answer the phone. Today, she could not remember which she had spoken to. But she had arranged to meet with one of the girls at the Club. Judi or Coral. She wondered which.

In the cramped bathroom, it took Nina a while to get dressed. She kept being distracted by her face in the mirror. Even before she washed the bran off, she did not look like the girl in the old smack adverts. The ones that said it screws you up. Just because she did smack did not mean she could not wash and comb her hair – although soapy water did make her feel squirmy sometimes – and put a little make-up over the blue-ish crescents under her eyes.

She dressed for the party, mainly in her best black. She favoured forties styles, with padded shoulders and deep pleats. She always wore long sleeves. Nina posed like a model in front of the tall mirror. She looked so much better since she started losing weight. She did not have to suck her cheeks in to appear glamorous any more, and she had completely lost her stomach.

She still thought she could get by doing modelling, but she never had the money to assemble a decent portfolio and that was what you needed if you wanted to get into the big money. She only had one nice photo of herself, and that was years out of date now. One of her regulars had wanted her to model for him, but he turned out to be interested only in private camera sessions. She did not want any of those photos.

She brushed the tangles out of her hair, feeling the scratch of the tines on her scalp. There was nothing wrong with parties, really. They were probably easier than modelling jobs.

More in control now, she got back to the telephone. After putting the receiver properly in its cradle, she picked it up and, flipping her book open to the number, called Coral and Judi. Knowing what they were like, they probably needed reminding about the meet. Their phone rang and rang until she gave up. She tried Clive again, but put the phone down before his machine could finish.

There were hours to go before Amelia’s ‘entertainment’, so she would have time to set something up with Coral and/or Judi, and to pull herself together.

3

While Anne waited for the policeman to come back, she listened to the hospital piped music. They were playing something strangled by a million strings. Irritated, she recognized ‘I Saw Her Standing There’ under the Mantovani massacre. Messages from administrators to doctors chirruped in the background like signals gone astray in deep space. The Synthesized Celestial Choir segued into ‘Do You Want to Know a Secret?’

Even under normal circumstances, she could not comfortably listen to The Beatles any more. They had been so much a part of her pre-adolescence. The four chord melancholies and ecstasies had turned scary. It had been ‘Helter Skelter’. They had gutted Sharon Tate in Hollywood, and shot John Lennon in New York. All that was left was musak.

Judi had been into groups with more honestly horrific names. Paranoid Realities, Skullflower, Coil, Bad Dreamings, The Manson Family Reunion, Three More Bullets and a Shovel. She would have spat on ‘Love Me Do’ and ‘Please Please Me’.

Still, The Beatles had been with her all her life. Anne’s first memory was of her father letting her stay up past her bedtime to watch them on The Ed Sullivan Show. Not the first time, but a re-run. Judi had not been born yet. Later, the Double White was the first album she had bought with her own money. She had played it over and over on the old phonograph in the cellar rumpus room of the summer house in New Hampshire. Cam had taken personal offence at ‘Revolution No. 9’, and so it automatically became her favourite track. Even so, she would lift the needle over it when he was not there.

Judi was around then, making her presence felt everywhere, all the time. She had been reading almost before she could put a real sentence together in her mouth, and father had taught her long division before she ever saw the inside of the school. There had been no doubt about it: Judi had been the clever child, the pretty child, the promising child. Cam was the first-born, and thus beloved of God (and his mother, Dad’s ex-wife). That left Anne as the nondescript one in the middle.

Now, Cam was as rich and famous as it was possible for a self-styled avant garde composer to be, Anne was working her way up the ladder as a journalist, and Judi was dead.

‘I’m sorry, miss, but I have to tell you that your sister is dead,’ Inspector Hollis had said. No tactful build-up, no euphemisms. The policeman had simply established that he was talking to Anne Nielson, and told her what he had to. She could not help but wonder whether he was familiar with her Aziz pieces. They had not been calculated to endear her to the Metropolitan Police. But she knew really that this was how everybody got treated.

There are a million stories in the naked city, and not enough words to go around. What with government cuts, a copper’s vocabulary would have to be pared down to the absolute minimum. No surplus circumlocutions, synonyms hoarded like golden acorns.

Back in November, Anne had interviewed an ex-marine who had written a good book about Vietnam. He never used the words ‘kill’ or ‘dead’, just ‘waste’ and ‘wasted’. That was bluntly the best way of putting it. Wasted.

Anne saw the doctor who was supposed to have looked at Judi when she was brought in. He was busy now, pulling apart the do-it-yourself mummy swathings wrapped around the head of a little West Indian boy. She glimpsed red cheeks, raw meat rather than blushes. This time, she was impressed by the doctor’s performance as he kept up a non-stop stream of soothing chatter for the boy and his visibly anxious mother.

With Anne, he had been offhand, awkward. She wasn’t his patient, just related to an inconvenient lump of deadness he could have nothing more to do with. Alive, you are a challenge; dead, you are an embarrassment.

There were uniformed soldiers, unarmed, in the corridor. With the ambulance drivers’ dispute dragging on, many local authorities were calling in troops to man the emergency services. Two squaddies, berets folded and tucked into the epaulettes of their olive-drab jerseys, were sharing a cigarette and a joke in an alcove, trying to keep out of the way. Their presence in the hospital made the place not feel like mainland Britain. Anne assumed this was what combat zone first-aid centres were like, in Belfast or in Central America. Even this early in the day, the casualty reception was busy. With the holidays starting, it was a prime time for accidents. Anne had had to do the hospital ring-round when she was starting out as a journalist, fishing for stories. Now, that seemed a long time ago.

Anne had been at home that summer when Judi was fifteen. She was freshly graduated from journalism college, doing bits for the local paper and working on the novel she never did finish. She had been a witness to what their mother, in one of her infrequent bursts of British understatement, called ‘Judi’s turn for the worse’. It was as much her fault as father’s, or Cam’s, or anyone’s. ‘There are some days,’ Judi had told her in a rare communicative mood, ‘when I think that life is an unending Hell of misery and desolation, and others when it seems merely to be a purposeless punishment, unending in its monotony.’ It was hard to come back with something like ‘yes, but what will you be wearing to the junior prom, sis?’

That summer, Judi had realized that being clever was not getting her what she wanted out of life, and so she had decided to be stupid instead. She had stolen money from Cam’s wallet and bought a Greyhound ticket to New York. In the city, it had not taken her long to find 42nd Street. On 42nd Street, it had taken her an absurdly, and probably mercifully, short time to find the undercover vice cop.

Father, the Great Man, had shrugged into a fit of inertia when the NYPD called, and so Anne had had to deal with it. Cameron Nielson Sr. came up with the bail, his agent kept it out of the papers, and Anne went to town to pull her little sister out of the pussy posse’s holding cells.

The next time, Judi had used her one telephone call to get in touch with a stringer for a paper so yellow that a dog could piss on it without making a difference. He had to be told who Cameron Nielson was, but he came up with the headlines anyway. NOBEL PRIZE-WINNER’S DOPER DAUGHTER IN B’WAY BUST. BAR-B-Q MAN’S GIRL IN SEX FOR DRUGS RACKET. Shit, that had been bad for all of them.

Anne thought again about The Call. Father could not talk any more. He had not written anything much since the late ’60s. But he had been the only Nobel laureate ever to write for Rock Hudson and Doris Day, and then have his script redone by a kid fresh from two episodes of The Mod Squad and some quickies for Laugh-In. Anne thought that humiliation had done more to Cameron Nielson than any of Judi’s exploits. More even than Hugh Farnham and his Committee. His only substantial work in the last ten years was The Rat Jacket, an intensely personal one-acter about an informer committing suicide. Widely interpreted as autobiographical, the piece – Anne suspected – would eventually be seen as one of his most important. There was talk of Robert Altman doing it as a television play with Harry Dean Stanton.

‘Miss Nielson,’ said Hollis, not unkindly, ‘we’re ready for you now.’

The policeman escorted her to the lift. He took a gentle hold of her upper arm and steered her. She was too drained to be annoyed by the imposition. The lift was large enough to accommodate several six-foot stretchers, and smelled like a dentist’s office.

‘We’ve contacted your brother. He was at the Grafton, like you said.’

‘That’s where he usually stays when he’s in London.’

‘Cameron Nielson? That’s a famous name.’ He was trying to make conversation, keep her mind busy. ‘Any relation?’

‘We’re his children. It’s Cameron Nielson Junior.’

‘On the Graveyard Shift at Sam’s Bar-B-Q and Grill. It’s a 20th century classic.’

‘That’s what they say.’

‘I saw it at the National when Albert Finney did the revival. With Donald Pleasence as Sam. Of course, I’ve seen the film…’

‘Elia Kazan directed that.’

‘…with Marlon Brando, Lee J. Cobb, Therese Colt and Eli Wallach and… who was the girl? The English actress?’

‘Victoria Page. My mother. And Judi’s. Not Cam’s. That was another actress, a woman who divorced Dad in the fifties.’

They were there.

It was not like morgues in the movies. They did not have walls with long drawers. The bodies were on gurneys like elongated tea trolleys, with green sheets over them. The air conditioning was breathing low, cooling the place even in December. The place could as easily have been a school kitchen.

Movie morgues were always antiseptic, as clean and dignified as chapels. This was dirty. The waste bins overflowed with plastic cups and used paper towels. Someone had left an oily car battery recharging on a wash stand, and the only attendant was a kid with an unstarched mohican. He wore a Cramps T-shirt under his soiled hospital whites and he was reading the Arts pages of The Independent.

‘Of course,’ said Hollis, ‘we’ve already identified her from fingerprints…’

‘Yes, this is just a formality, but it has to be done. Right? You have forms to fill in before you can forget her.’

She was immediately sorry for snapping at him. After all, he was not PC Erskine. Hollis continued without taking notice. He must be used to dealing with irrational people.

‘You knew that your sister had a criminal record?’

‘Oh yes.’ Here and in New York. Possession, soliciting, resisting arrest, carrying a concealed weapon, whatever. Judi’s Interpol file was probably more substantial than anything Anne had written.

Hollis lifted the sheet himself.

There had been a mistake. It was not Judi.

This woman was old. All the substance beneath her mottled skin had drained away. She looked like a life-size shrunken head. The hair was dyed a blotchy black, but the roots were the white-yellow colour of drought-killed grass.

‘It’s a mistake,’ said Anne, disorientated. ‘It’s not her. She was…’

‘Twenty-five. We know.’

‘But…’

‘Look again.’

The eyes were open, rolled up into the skull, whites red-veined. The dead old woman’s mouth was shrunken, but still firm. She had all her teeth.

Not wanting to, Anne touched the face. There was a spot on the upper lip, where Bogart had a scar, where Judi had a mole.

‘It can’t be. How…?’ She looked at Hollis, and answered her own question. ‘Drugs. Heroin?’

Hollis gently eased the left arm out from under the sheet. He ran a finger over the extensive abrasions. Amid the bruises, Anne could see fresh and ancient pinpricks. And there was Judi’s crescent scar over the inoculation marks. A childhood scrape with an electric lamp.

Anne wanted to cry, to break down, to give up.

Hollis was talking, almost lecturing.

‘She was an addict. We know that. Recently, there have been some quantum leaps in the drugs industry. They don’t need to import as much opium-derived heroin as they used to. The stuff can be synthesized in laboratories. Designer drugs, they’re called. From California, originally. The stuff is cheaper, purer, more debilitating. Strictly, it’s not even illegal yet. I’ve seen senile teenagers. It affects the metabolic rate. The processes that make you grow old… I don’t really understand this… they get speeded up…’

Poor Judi. Wasted. Her whole life literally used up. Anne looked at the old woman’s face and saw the child her sister had been. Judi had not died easily.

Hollis covered Judi again, tucking her in.

‘Did she do this to herself?’ Anne asked.

Hollis looked at the floor, not quite shrugging.

Anne did not say any more. She was too good a judge of her own character. She knew what she wanted. It was the same when their mother had left, and when the novel had not worked out, when she had first heard of Charlie Aziz, and when father had wound up mute in a chair. For her, it was only natural.

She wanted someone to blame.

4

Even the Kind dreamed. But with the passing of so many years, the old man had outlived his imagination. All his mind had … left was the almost unbearable weight of memory. There was so much he could no longer consciously recollect. Yet all of it existed, untapped by his waking self, in his night thoughts…

By the standards of centuries he would live to see, it had hardly been a battle at all. A routine patrol of six or seven horsemen with maybe two lances between them had come upon the enemy encamped in a shallow valley and, against his orders, engaged them. The din had carried in the strong winds, and his own camp had been roused to the combat. His hand thus forced, he had committed his men to the skirmish. It had turned into a minor massacre.

Taking both armies into account, there were perhaps one hundred dead. But he was well pleased. The English captain had been taken, and he had spent a long, rewarding afternoon with him. The man had been a genuine soldier, not some royal cousin assigned a command to keep him out of treason and plotting at home. He was much more resilient than the children who were his frequent guests between wars, but, in the end, he had yielded as completely as the scrawniest peasant brat.

He was satisfied, glutted, complete. Beneath his helmet, the tangle of his hair, grey-streaked at dawn, was a match now for the purest sable. His lieutenants no longer remarked upon the changes in him. By now, they were used to his cycles and simply put his occasional youthful appearance down to sorcery. A few of them were given to boasting about their master’s skill in the Black Arts, and that could be useful from time to time. Poor Sieur Barbe-Bleue, meticulously obsessive as ever, was even trying through atrocity and alchemy to ape him, searching in the ruined and abused flesh of small boys for an elusive immortality. But some of his other officers, an unfortunate number who would soon learn better, had almost forgotten to fear him. For them, the English captain should have been saved for a ransom, not wasted on pleasure.

He had his ragged cloth-of-gold pitched on the bloody grass, about where the fighting had been most concentrated. He looked forward to stretching out on the insanguinated ground and luxuriating in the residues as others would in a heated and perfumed bath.

After the Englishman was exhausted, and consigned to the bonfires with his followers and the dead horses, he paid a visit to the girl.

She was squatting between the fires, her face still streaked with blood, her hands clasped in prayer. Sometimes he wondered what she said to her saints. Did she apologize for the extra load of souls that were lining up outside the Gates of Heaven as a result of her conversations with dead divines?

He knelt before her, and took her young head in his hands. His fingers slid into her cropped, coarse hair. He picked out a hard-shelled parasite and popped it between thumb and forefinger.

He, the Monster, kissed her, the Saint.

That year, he favoured little boys. But his congress with the girl was different. Her skin was permanently marked with the weave of chain mail. During the physical act of love, she called him ‘father’ several times. Whether she meant her father in the village, a father at the church, or the Father in Heaven, he could not say.

The wind tore at the already tattered walls of the tent, detaching wisps of golden thread that floated over the camp. A detail was stripping the dead of their armour, and piling it up. The fires burned fiercely, roasting and consuming carcasses with much crackling and hissing. The soldiers sang, words about intercourse with goats set to sacred tunes.

Every so often, there was a gurgling cry. He had ordered the whores to comb the battlefield, cutting the throats of the wounded, no matter whose colours they wore.

Close to his already dwindling body, the girl slept, doubtless dreaming of the young king and the angelic voices that whispered inside her skull. He touched his head gently to hers and sadly tasted the emptiness within. Briefly, he thought there was something, but it was just a memory of the unending winds that forced this girl, and all like her, to and fro without regard.

Strangely, he did not feed off her.

5

There were Monsters, Anne knew. It was a secret she shared with Judi. Their father had met a Monster, and lost, before they were born. Anne knew all about it. She had seen the kinescopes. She knew the face of the Monster, and that their family bogeyman had once had a name, Hugh Farnham, but that was the least of it. He went on forever, revealed only by a tone of voice, a strident attitude, an indestructible set of mind, a few whistled bars of an old film theme tune.

‘You have to stop thinking in absolutes,’ her journalism tutor had told her. ‘Life isn’t a movie, with good guys and bad guys, heroes and monsters.’

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!