7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

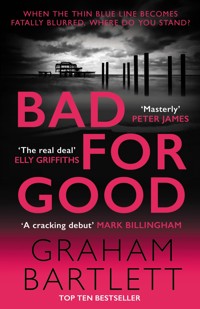

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Jo Howe

- Sprache: Englisch

'Brutal, dark and laced with violence ... Peter James had better watch out, he has a new competitor' DAILY MAIL 'A masterfully spun tale . Intense pace, striking characters and a riveting denouement' IRISH INDEPENDENT 'Gripping' PETER JAMES 'Thoroughly absorbing' ELLY GRIFFITHS How far would you go? The murder of a promising footballer, son of Brighton's highest-ranking police officer, means Detective Superintendent Jo Howe has a complicated and sensitive case on her hands. The situation becomes yet more desperate following devastating blackmail threats. Howe can trust no one as she tracks the brutal killer in a city balanced on a knife edge of vigilante action and a police force riven with corruption. 'Cracking' MARK BILLINGHAM 'Engaging' M.W.CRAVEN

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 497

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

5

BAD FOR GOOD

GRAHAM BARTLETT

For Julie, Conall, Niamh and Deaglan. You make all my dreams come true xxx

I always tell authors that the story and characters must come first. With that in mind, this is a work of fiction, hence some structures, titles, locations, even some police procedures, have been modified to serve the story and the characters for your enjoyment.

Contents

Part One

1

8.30 a.m., Friday 27th April

As the steel baton shattered his right kneecap, Wayne Tanner wished he had broken his golden rule and driven away from trouble this time.

‘What the fuck?’ he cried, as he concertinaed into the dirt. Writhing and screaming in agony, he barely registered the second swing as it disintegrated his left shoulder.

He’d had ample opportunity to lose the black Audi tailing him out of Brighton city centre, but that was not in his nature. Now, trapped in the remote Ditchling Beacon car park and hemmed in by four truncheon-wielding thugs, there was no way out.

His reluctant yet desperate attempts to clamber away only resulted in his flaccid leg shooting fiery pains through him with every drag. He’d only managed a couple of yards before another flurry of strikes rained down, crippling his other knee and left forearm.

‘You’re fucking killing me!’ he yelled, as he heard his white van cough into life. ‘Whatever it is, you’ve got the wrong bloke.’

‘Oh, I don’t think so, Wayne,’ came the reply from the impassive spectator who then raised his hand, which immediately stopped the beating.

‘Who the fuck are you?’ Wayne cried.

‘Friends of Susie’s. Or rather, her dad.’ Wayne detected a northern accent but couldn’t place it.

‘Reg?’

‘See, we are on the same wavelength.’

‘What are you on about and where’s he going with that?’ he shouted, as his van disappeared onto the Beacon Road.

‘We’ll take good care of your motor. Can’t say the same for you though,’ the man said as he pile-drove his boot on Wayne’s shattered leg.

A flock of gulls screeched into flight.

‘See, Reg never liked you. Couldn’t see what Susie saw in you. So when you put her in hospital, well he wasn’t best pleased.’

‘But I got nicked for that. I’m on bail and I can’t go near her again.’

‘Yet even if it gets to court, you’ll get a small fine and a smack on the wrist. Reg didn’t think that was enough, so asked us to help.’

‘But …’ Tanner pleaded.

The man turned to the others, their batons at the ready. ‘Get him in the car.’

Wayne’s howls went unheeded as they dragged his crumpled body to the Audi. Pausing to plasticuff his wrists together, they shoved him into the back seat.

As the door slammed behind him, one of his attackers slid in the other side and shoved Wayne’s head forward into his lap.

‘Where are you taking me?’ he groaned, as the car wheel-span out of the car park.

The man fiddled with the satnav, then turned and said, ‘Let’s just say, you’ll soon wish you’d never met Susie Parker.’

2

8.00 a.m., Monday 30th April

Detective Superintendent Joanne Howe had worked harder than most to get where she was. Some kinder souls, unaware of her professional and personal struggles, described her as lucky. Her more vicious rivals attributed her holding the most coveted of detective jobs to positive discrimination.

Her status was the last thing on her mind though, as she scurried between her sleek new kitchen and the bomb site of a lounge where her boys – Ciaran, four, and Liam, three – were spooning Weetabix everywhere but in their mouths while glued to an eternal loop of SpongeBob SquarePants on Nickelodeon.

At forty, children and her dream job, the Head of Major Crime, had come late in life and now, as those two frenetic worlds collided, she wondered why on earth she had craved them for so long. Her husband, Darren, was her rock – when he was around. As an investigative journalist for the Daily Journal, his habit of zipping off to far-flung cities for days on end was beginning to grate; even if that was how they’d met. At least now that she was in charge, she could work her turn as the duty Senior Investigating Officer – SIO – around his absences. In theory.

The familiar chirp of her work mobile phone snapped her from her domestic chaos.

Eventually locating it nestled under the sheaf of Major Crime Unit performance reports she had been fretting over last night, she tapped ‘accept’.

‘Jo Howe, can I help you?’

‘Morning ma’am, it’s the duty inspector at Brighton here. Have you got a moment?’

Jo scurried into the lounge, grabbed the cereal bowls and mouthed, ‘Brush your teeth,’ to the boys.

‘Yes, go ahead.’

‘Are you duty SIO today?’

‘No, but you’ve got me now, so what is it?’ she replied, battling to keep the irritation out of her voice.

‘Oh sorry, I was looking at the wrong on-call sheet. Well, if you’re sure. We’ve had a misper reported. Bloke called Wayne Tanner. He’s been missing since Friday morning. I wouldn’t normally bother you, but he was last seen when we bailed him from custody for a domestic assault.’

‘Woah. Rewind a second. Why are you worried about him? I’m taking it he had a bust-up with his partner?’

‘Yes ma’am, he punched his girlfriend. It’s just odd. There’s no trace of his van, he’s not turned up at his usual haunts, no trace of his phone and no activity on his bank. And he only had £3.50 when he was released from custody.’

‘OK, I’ll have a look at it, but raise it at your own DMM too. Give me an hour, as I have to wait for my childcare to arrive.’

She detected a faint sigh from the other end of the line. She bet the blokes never got that reaction. That was the police for you. If she said she was at the football and would come out at half-time, no one would bat an eyelid. Say, God forbid, that you have kids that need looking after, then the chauvinists got all sniffy. But she always made that point, as part of her crusade to chip away at the stigma that came with being a working mum in the police.

Monday mornings after his duty weekend sparked Phil Cooke’s mischievous side.

Having spent most of his thirty-five years’ service at Brighton and Hove Division, at every rank from PC to chief superintendent, he knew at first-hand the carnage his officers would have endured since Friday.

Age had been kind to him. The wrong side of fifty, but his passion for the weekly five-a-side football tournament and a job where meals were a rare luxury stemmed any middle-age spread. His sandy close-cropped hair was holding its own against the creeping grey that afflicted so many of his peers. Only his ruddy complexion hinted that life – or the drink – was taking its toll.

As the divisional commander, he bore a huge responsibility to the City’s quarter of a million residents, eight million visitors and the ever-thinning blue line of around four hundred cops. In awe of the brave young men and women who faced violence and misery on a daily basis, he conceded that they worked considerably harder than he and his erstwhile colleagues ever had.

The changing face of policing over the years meant that out of office hours, the fort was held by the response teams and CID. They ran themselves ragged racing from call to call, scraping up the detritus that went hand in hand with a city that never slept.

Come Monday morning, everyone else played furious catch-up, struggling to get their heads around the chaos of the last sixty hours. No one wanted to be exposed at the Daily Management Meeting, or DMM, as lacking grip.

Having kept up to speed over the weekend, what Phil didn’t already know wasn’t worth knowing. So, exploiting the deferential police culture, he loved to breeze into offices, distracting and stressing his industrious juniors with inane small talk.

Ambling across the ramshackle open-plan Divisional Intelligence Unit – DIU – he nodded to the dozen or so bustling detectives and analysts as he beelined towards his old friend, DI Bob Heaton, who was beavering away in his glazed corner office. Bob’s rumpled appearance, tatty red-and-white checked tie, already at half mast, and his creased and smudged striped shirt suggested, to those who didn’t know him, that rather than having just arrived at work he’d spent the night traipsing through some gruesome crime scene.

‘Morning Bob,’ Phil chirped as he entered the poky room. ‘How was your weekend?’

‘Oh, hello sir. Yes, good thanks. Fairly Q here from what I can see,’ replied a harassed Bob, observing the police superstition of never saying the word ‘quiet’ out loud.

‘Really? Those chemist shop burglaries looked interesting. Still, save me the details until DMM.’

‘Oh right. Yes, I, er, I haven’t got to those yet.’

Phil took a seat, then inwardly smirked as he saw the DI crumble in the recognition he would never get the next ten – or maybe fifteen – minutes of his life back.

‘Found yourself a new woman yet?’ asked Phil, piling on the agony. They had been DSs together years ago and were a formidable team. Since Bob split from Janet ten years ago, his reclusive lifestyle bothered Phil.

‘Ha! No, not yet. How’s your lot?’

‘Harry’s being tipped for a professional contract at the Albion. Got all his footballing skills from me, you know,’ he joked. ‘Ruth’s not so good though. That last lot of chemo completely wiped her out. She’s tough but I’m not sure how much more she can take. They’re even talking about hospices.’

‘Kyle?’

‘Oh, yes, he’s OK. Still mucking about with his band or something.’

‘That’s good for the boys but I’m so sorry about Ruth, mate.’

‘No worries, we’ll get through. Look, I better let you get on. Don’t forget about those chemist breaks, now will you?’

‘As if,’ replied Bob, spotting an unfamiliar sag in his boss’s posture as he shuffled out of the door.

The ‘Sussex by the Sea’ ringtone blaring from Phil’s phone drew flashes of irritation as he made his way out of the DIU.

The caller ID sent his mood plummeting to new depths. Every Monday morning his boss, ACC Stuart Acers, phoned each of the three divisional commanders on his drive to Sussex from his sprawling Surrey pad. Despite having a staff officer, he insisted on hearing any dramas direct from his chief superintendents.

‘Morning Stuart,’ said Phil, as he ambled up the stairs back to his own office, struggling to mask the contempt in his voice.

‘Morning Phil. How’s Brighton looking?’

‘Fine thanks. Fairly Q weekend. Some chemist breaks that Bob Heaton is all over, the usual drug dealing on the estates, a couple of robberies and half a dozen mispers. One of them was in custody for domestic violence last week but I suspect he’s just lying low.’

‘Sorry, you broke up a bit there. Must have been driving through a dodgy area. Not as dodgy as your city though.’

Tosser, thought Phil. ‘Do you want me to go through it again?’

‘No. Don’t forget, next week’s Neighbourhood Policing Board is your last chance to come up with the twenty per cent efficiencies we need from your division before I find them for you.’

‘Look, I’ve told you, you’ve already cut me to the bone. Most of my teams haven’t had a complete set of rest days off for six months. Any more cuts and I might as well put up the “Closed” sign.’

‘Sorry, you broke up again there. Anyway, good luck with those savings proposals.’ The abrupt silence told Phil this was not up for debate.

‘Knobhead,’ Phil muttered as he reached the landing, oblivious to the red-faced young PC scurrying past.

*

No one dared call him Marcus nowadays.

Not even his despairing parents, who were now little more than his hoteliers on his rare trips back to London. Since he had ‘gone country’ to run the north Brighton drugs supply line, he had no further need for them.

Marco, as he insisted on being called now, found ‘food’ – heroin and crack cocaine – a cinch to shift. Since the London markets had been flooded, the supply almost exceeding demand, exploiting what others quaintly labelled county lines was child’s play. The kingpins in the capital sent up-and-coming gang members to rural towns and cities to open new markets and create new addicts.

All Marco had to do was shift the drugs and return the spoils up the line. He strutted like he owned the patch, which spanned from Preston Park to the city’s boundary close to Waterhall, but still he remained vigilant.

His only real fear was if the police confiscated his stash. There were no excuses for that. His debt to the bosses could run into thousands and the consequences of default were brutal. A machete up the arse would render him shitting in a colostomy bag for life.

Soon after being recruited at the relatively late age of fourteen, he quickly worked out who to kowtow to, and who he could crush. He took risks, plugging drugs into orifices that, until then, he presumed had only biological functions, but he instinctively knew when to be cautious. His nous quickly impressed his London-based masters and within two years Marco was assigned his own line.

Too many of his peers had failed and paid the ultimate price, so he knew not to let his guard down, and never to show weakness. His ruthless and public destruction of anyone who showed him even the slightest disrespect or moved to usurp his precarious position was well known; beef with Marco and you’d get the pick of mobility scooters.

Tonight, as usual, he was touring his manor, checking up on his minions. He was beyond handling the food himself – far too risky – but he needed to show who was boss.

He ripped about the streets on a black Mongoose BMX bike – his ped. What it lacked in prestige it more than made up for in dexterity, always outrunning and outsmarting any overly inquisitive cops. It was especially useful after dark, its colour and stealth melting him into the gloom.

He whipped around the corner on to Ladies Mile Parade, jack-knifing the back wheel to a halt, smiling when he saw his runners all present and correct.

‘Hey Marco, what’s happening?’ said Junior, lurking in a charity shop doorway. Fifteen-year-old Junior’s career had ground to a halt last Christmas after his sluggish bulk enabled a rival gang member to chase him down. The hospital managed to fix the two stab wounds to his leg, but Marco was less than pleased with the hassle of having to firebomb the other gang leader’s grandmother’s house to teach respect.

‘S’good Junior. How’s t’ings?’

Junior flashed five fingers, indicating that he and the three younger hoodies, cowering two paces behind, had collected about £500.

‘Not bad. Any calls for me?’

‘Nah.’

Marco eyed an approaching, battered bottle-green Toyota Yaris. Sensing his apprehension Junior said, ‘He’s cool. A regular.’

Marco loathed being so close to a deal, but he knew to hide his unease from his lackeys. He watched intently from the shadows.

A flick of Junior’s head sent the smallest of his three acolytes forward. The boy swaggered to the parked car and darted his hand in and out of the open passenger window. Marco nodded. He made a mental note to find out the boy’s name. He’d seldom seen such a deft deal.

The Yaris sped away, business done.

‘Oi! I know what you’re up to,’ came a sudden shout from the direction of Patcham High School opposite.

A figure, dressed in a green sweatshirt and blue joggers – clearly thrown on in a hurry – marched from the school across the road.

‘I saw that. You just passed something into that car. I’ve called the police and they’re on their way.’

Marco pulled his black-and-red bandana up to cover his nose and mouth, tightened the cords of his blue hood around his face and stepped out to confront the man.

‘Eh, beat it Grandad,’ he hissed.

‘Says who? I’ve seen your sort before. You come here selling your muck, scaring decent people off the streets. I’m not having it.’

The caretaker was now squaring up to Marco, Junior standing at his boss’s shoulder. The three younger boys had dissolved into a doorway.

Marco stepped forward.

‘Fuck off back to your little wifey and leave the streets to the big boys.’

‘I used to eat scum like you for breakfast,’ he replied, puffing himself up to his full five foot seven inches.

Marco didn’t want a fight, but people couldn’t go round calling him scum; that was disrespectful. With the faintest flick of his neck, Marco’s headbutt floored the caretaker.

‘In there,’ Marco told Junior, pointing to a jet-black alleyway between the shops. Each grabbed an arm and pulled the dazed man out of sight.

When Marco and Junior emerged, blood splattered across their fists and white Nike trainers, they spotted the three youngsters huddled in the doorway. ‘Split,’ Marco ordered, then tutted when he saw the fresh vomit dribbling down the smallest one’s hoodie.

He knew none of them would sleep that night, but they had learnt a valuable lesson, and that made it sweet.

3

7.30 a.m., Tuesday 1st May

The following morning Phil traipsed, bleary-eyed, into Ruth’s bedroom, mug of tea in hand, his uniform shirt scarred from the hasty ironing session.

He hated that they now slept apart but she had insisted, especially after chemo. Her nausea, together with the numbness and tingling in her hands and feet, guaranteed sleepless nights. Despite his protests, she insisted that if he was going to look after her and the city he loved, the last thing he needed was being kept awake by her tossing and turning.

‘Morning love,’ he whispered, careful not to jolt her from a rare but inevitably shallow sleep.

‘Morning darling. Oh thanks, I’m parched,’ she croaked, shuffling up the bed, her arm outstretched to take the tea.

‘Here, let me,’ Phil insisted as he rearranged the pillows before passing over the Brighton and Hove Albion FC mug. He perched on the side of the bed. ‘Good night?’

‘Terrible, since you asked. You?’

‘Not too bad, considering. Is it tomorrow the Macmillan nurses are coming round?’

‘No, it’s … Oh God, pass me that bowl, quick.’

Phil grabbed the blue washing-up bowl that never left Ruth’s side, holding it under her chin just in time to catch her dry retch. He had seen some awful things in his life, but watching the love of his life – her beautiful hair just wisps now – waste away in such pain was killing him.

When she stopped, he passed her a pink towel from the bedside table. She dabbed her mouth as he deftly wiped away his tears before she noticed.

‘Sorry, oh I feel so rough. She’s coming on Thursday afternoon I think.’

‘OK, I’ll take a few hours off.’

‘No need. I’ll be fine. The boys are around.’

‘No, it’s my place to be with you. You can’t expect them to hear conversations like that.’

Their sons, Kyle and Harry, were the loves of their lives. Just eighteen months between them they arrived, after years of infertility, like London buses. Despite being chalk and cheese – Kyle, the eldest at twenty, a musician, Harry a gifted footballer – they were good mates. Since Ruth fell ill, they were great around the house but had their own lives to lead. Phil vowed to become as involved with Kyle’s music as he was Harry’s football. Ruth had ribbed him about living his failed soccer dreams through his younger son, once even using the ‘f’ word – favouritism.

He couldn’t believe he’d once nearly thrown it all away.

‘Hadn’t you better get going? I’ll get the lads to help me up.’

‘Blimey,’ he said, checking his watch, ‘I better had, but I’m taking Thursday afternoon off, no arguments.’

‘If you say so,’ she muttered as he pecked her on the cheek.

‘Love you.’

‘Love you, too,’ she said as he shuffled out of the door, choking back more tears.

*

Phil grabbed his chestnut-leather shoulder bag from beneath the stack of jackets on the newel post. This modish accessory was last year’s Father’s Day present from the boys, determined to drag him into the twenty-first century. Apparently, his battered black attaché case no longer cut it.

Picking up his work and personal mobiles from the radiator shelf by the front door, he shouted a general ‘bye’ back into the house, releasing the three security locks.

As he trudged down the path towards his car, he vowed – not for the first time – that on his next day off, he really would tackle the garden.

The bleep from his key fob flashed the lights on the police-issued white Ford Mondeo parked just outside the front gate. He slung in his bag and settled in the front seat.

As he slammed the car door, his work mobile chirped.

‘No rest for the wicked,’ he muttered to himself glancing at the screen. ‘Jesus,’ he exclaimed.

‘Have you heard what happened last night?’ bellowed ACC Acers.

Fuck you, mouthed Phil.

‘Stuart, I’ve just got into my car, so feel free to enlighten me.’

‘I’ve had Penny Raw, the City Council Chief Executive, on the phone …’

‘I do know who Penny is,’ interrupted Phil.

‘She is livid. The caretaker of one of their schools was beaten up last night.’

‘I’m very sorry to hear that.’

‘So you should be. He called the police reporting drug dealers opposite his house. When he got fed up waiting, he went out to confront them. He’s in intensive care for his troubles. Massive internal injuries and he’s in an induced coma. What’s going on, Phil?’

‘I just told you, this is the first I knew of it.’

‘I mean with your city, you idiot …’

‘Now look here …’ Phil just managed to bite his tongue.

‘No, you look. I have had enough of fielding complaints about your inability to provide the most basic service. Get a grip. I want an update by ten o’clock,’ he demanded, then the phone went dead.

‘Twat,’ shouted Phil at the inert phone. It wasn’t the poor caretaker Acers was worried about, it was how it looked for him and his career prospects. To Phil, the ACC had already been promoted three ranks above his level of competence.

Reluctantly, he scrolled through his contacts to find the number of his deputy, Superintendent Gary Hedges. He hit ‘call’ before starting the engine, letting the hands-free kick in, as he squeezed the car on to the carriageway.

Gary answered within two rings.

‘Afternoon, old fella. Nice lie-in?’ joked Gary in his South Wales lilt.

‘Piss off. Some of us have actual lives to lead. Look, Acers has been chewing my ear about some caretaker getting a beating last night. Do you know anything about it?’

‘I’m already on it mate. Frank Whitehead, caretaker of Patcham High School. He’s in a coma in intensive care. His missus says he went to have it out with some druggies outside their house.’

‘Not Marco’s lot again?’

‘Dunno. Anyway, when he didn’t come back, she went out and found him sparko in an alleyway.’

‘Holy shit.’

‘Yeah, she’s distraught but won’t leave his bedside. House to house, as ever, revealed fuck all so once again we’re at a loss.’

‘That’s the third one in as many weeks.’

‘Fourth.’

‘Acers said the victim tried to call us before going out there.’

‘Yeah but the control room told him it would be at least two hours before anyone would get to him.’

‘Two hours?’ asked Phil as he darted across Preston Drove to head along the east side of Preston Park. ‘How many did we have on last night?’

‘Eight.’

‘What, eight cars?’

‘No, eight officers – across the whole city. By then all but two were tied up in custody.’

‘Jesus,’ Phil replied, exasperated. ‘So I take it CID are picking this up?’

‘In your dreams. If we gave every assault to CID they’d sink.’

‘This isn’t a black eye after some handbags in the pub, Gary. Sounds like he’s touch-and-go. If it is Marco’s gang, I want them nicked and soon.’

‘You’re sounding like Acers now. I’ll do what I can but we’ve got twelve missing people, fourteen overnight burglaries, two rapes, an armed robbery and a couple of protests to deal with.’

‘Another day in paradise,’ Phil sighed. ‘Has that Tanner bloke turned up yet?’

‘What, the all-action hero who beat up his girlfriend? No. Jo Howe’s had a look at it, as he was in custody before, but she’s pinged it back to us. I suspect he’ll crawl out from whatever stone he is under when he’s ready.’

Phil’s heart quickened on hearing Jo’s name. ‘I hope it crushes him first. Right, crack on Gary, I’ll be with you in a bit. White, no sugar for when I get in if you don’t mind!’

‘Homemade cappuccino?’ replied Gary, mimicking a phlegmy hawk from the back of his throat.

‘You repulse me,’ said Phil, killing the call, his melancholy swamping him again as his mind turned back to Ruth.

*

‘Let me out you wankers! I need a doctor!’ yelled Tanner as he writhed on the cold stone floor.

‘Wind your neck in,’ spat a voice next to him. ‘This isn’t the bloody Hilton.’

‘Fuck you. I’m in agony here.’

‘Yeah, yeah. Wait till you’ve been here as long as us. And we’re the lucky ones.’

‘If I don’t see someone soon I’ll be crippled for life. With all the shit and piss I’m wallowing in, I’ll get fucking gangrene.’

The tiny cell in which he and four others were crammed was literally from the dark ages. It was not so much the lack of light – a crack in the roof threw an occasional blade of sunshine, when the rain wasn’t streaming through. It was the stench, the bone-chilling damp, and the unrelenting cold and hunger that drove him crazy.

‘It’s not just you,’ came a second voice from behind. Tanner could only imagine what his room-mates looked like. This one, he decided, was a pasty academic: thinning black hair, fingernails chewed to the quick. His tweed jacket probably reduced to rags.

‘I’m the only one I give a shit about. Get me a fucking doctor!’ he yelled at the door again.

‘You’ll need an undertaker if you don’t wind your neck in,’ came a third voice – gruff, clipped, brash. A military man? Tall, muscular, ramrod no doubt. Tanner made it his business to avoid the sergeant-major – well, as much as you could in a six-by-eight-foot cubicle with one stone bench and a single shit-bucket in the corner.

He shuffled away to the lichen-encrusted wall, his chest heaving with despair.

*

It was six months since Helen Ricks had scooped promotion to chief constable and she was growing impatient with Sussex Police.

Her previous force, London’s Metropolitan, had its share of bigots and cliques, but there was an embedded intransigence here. Outwardly she was warmly welcomed, but she’d yet to find anyone she could trust.

In her long experience, she knew it sometimes took a monolithic crisis to jolt the police into change. She had lived through the botched investigation into the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence in South London in 1993 and – somehow – avoided the spotlight during the enquiry into undercover policing.

If only they knew.

She just hoped it wouldn’t take something like that for her new force to face the fact that the good times, if they ever existed, were over.

When she first arrived in the force, the contrast between the imposing exterior of the Grade I listed building which housed the diminishing Force Command Team and its utilitarian interior, made her chuckle. All fur coat and no knickers.

Sharing her anodyne, yet functional open-plan office with her deputy and the assistant chief constable, she guessed whoever defined these cosy working arrangements as efficient progress had never worked with Stuart Acers.

She kept her bleached MDF desk obsessively clear. It wasn’t that she had no personal life, it was just best kept to herself.

This morning had not got off to a great start. Her boss, the police and crime commissioner, Teresa Sutton, had already balled her out over the epidemic of violence blighting Brighton and Hove, and now ACC Stuart Acers’ booming West Country burr was resounding down the passageway.

‘Just bloody sort it,’ he bellowed, bursting into the office, mobile phone clamped to his ear.

‘Morning Stuart.’

‘Do you know, this job would be a piece of piss if it wasn’t for the staff and the public. They make my life a bloody misery.’

‘That is the job though,’ said Helen.

‘You’ve got to sort out Phil Cooke,’ he said, as he hefted his tall-as-wide frame into the groaning swivel chair. ‘He’s past it. Can’t we get rid of him? He refuses to find the cuts we need, and on top of that his troops don’t even answer the bloody calls.’

Helen gave Stuart a wry look. He was too dim to spot the irony in his two bones of contention.

‘You bleat about Philip day in and day out. I’m not moving him, not this close to his retirement. He’s good for Brighton, the locals love him. Just take some responsibility, will you?’

‘It’s not bloody difficult. Why can’t he just get a grip?’

‘Stuart, if it’s not “bloody difficult”, you help him. Look, he’s got a lot going on at the moment. His wife’s dying of cancer. Cut him some slack for once and be part of the solution. Get alongside him and come up with another way to skin the cat. Use that creative streak you hide so well.’

*

Few people scared Crush, certainly not physically, but there was a coldness, a brutality, in his immediate boss that terrified him.

His imposing frame, tempered through his obsession with iron-man challenges, quivered – ever so slightly – as he rapped on Doug Robinson’s office door.

The summons had left no room for doubt or discussion – he was in the shit and if he knew what was good for him, he would get his sorry arse over to Ocean House, nestled in the shadow of Brighton Railway Station, tout suite.

It could be any number of things that had riled the boss. Demands like this usually sprung from nowhere, so far as Crush could see. Robinson’s explosive temper was legendary, often sparked by some minor irritation. He had once sent his secretary home in tears, bawling her out when she brought in his tea and bourbons, because she had forgotten he had given up chocolate biscuits for Lent.

‘Come in,’ the voice bellowed.

He did as he was told, and was relieved his boss was alone. No audience. It was not unheard of for him to call one of his minions over for a bollocking just so he could show off to a business partner or some prospective client.

Crush stepped over to the smoked-glass desk, from behind which Robinson glared, sweat glistening on his bald pate. Avoiding eye contact, Crush sat down in the black leather chair opposite. That was his one insubordination – whatever the balance of power, he was not going to stand like a naughty schoolboy.

‘You wanted to see me, boss,’ he said, his Tyneside brogue camouflaging his fear.

‘Too right. I’m hearing that shit Tanner you grabbed on Friday put up a bit of a fight.’

‘Nothing we couldn’t handle.’

‘I see,’ Robinson replied, resting his chin on his steepled fingers. ‘So, it was a standard snatch then. Just what the client asked for, yes?’

‘Of course.’

‘Then why has he got two broken legs, a broken arm and a shattered fucking shoulder?’

‘What does that matter? He just needed softening up, that’s all. You’ve never worried before.’

‘Don’t take me for an idiot,’ yelled Robinson, his laser-blue eyes locked on to Crush’s. ‘This was a Premium Job, not some scally or paedo we swept up like garbage. The client paid a five-figure sum for a bespoke service. He was very specific, a grab, a mild roughing-up, a few nights in the dungeon, then dumped a couple of hundred miles away with some flesh wounds to remind him not to return.’

‘I’m sorry boss, but no one told me that. I just thought it was the standard job.’

‘Well it fucking wasn’t,’ bellowed Robinson, slamming his fist on the desk, his mug dancing in protest. ‘When I told him what happened he started to bottle. Talked of going to the police, denying everything.’

‘Do you want me to sort him out, boss?’

‘God no. I’ll deal with him.’ He paused, took a deep breath, rubbed both his hands over his head then prodded a menacing finger towards Crush. ‘If you ever ignore the brief again or fail to keep those gorillas under control, you’re out and we don’t pay severance.’

‘Yes boss. Sorry.’

‘Right.’ Robinson moved on, much calmer now. ‘I need you and a team in Brighton. A caretaker was beaten half to death by drug dealers in Patcham last night. He’s not the first one to be left with tubes sticking out of him and booing relatives at his bedside either. Word is he called the Old Bill and when they didn’t turn up, he decided to front them up himself.’

‘Stupid twat.’

‘Yeah, that’s as may be, but we need to sort this lot out once and for all. Get down there and send them a message.’

‘So, to be clear, is the old caretaker paying for this? If so, what does he want exactly?’

‘No, this one has come from the Boss, so it’s part of our community service. You’re not necessarily looking for the geezer that beat the old man up, you’re just going to send a shockwave through these pipsqueak gangs.’

Crush knew the mere mention of ‘the Boss’ curtailed any further discussion. He had never met this mythical puller of strings, but had been around long enough to know that the one-off grabs were a paid service: people let down by the police, forking out for their own justice. Orders for the more general snatches, beatings and vanishings came from on high. He presumed one funded the other and what the Boss wanted, the Boss got.

‘Just a word of warning, guv. We are getting very short of space at the dungeon. Probably only room for about half a dozen more.’

‘You need the lorry?’

‘Yeah, tonight or tomorrow I’d say. If we can get rid of around ten that should do us for a week or so.’

‘OK, I’ll see what I can do. It’ll be at least three days. That’s if we can get the stoker down here today to get the furnaces up to temperature.’

‘Thanks boss.’

‘It might be best if Tanner’s one of them. He’s become a complication and the Boss hates complications.’

‘Consider it done,’ Crush replied, struggling to conceal his grin until he was well clear of the office.

4

6.10p.m., Tuesday 1st May

Perhaps if Harry Cooke’s head wasn’t buzzing with his incredible news, he might have spotted the watcher as he skipped off the number 11 bus.

Perhaps if he had not been so engrossed bragging on Snapchat, he might have noticed him trailing his progress as he strutted across the swarming A23 towards Withdean Park, his shortcut home.

But his head was turning cartwheels as he made the call he was most excited about.

‘Honest Dad, I reckon it was between three of us, but when the gaffer called me in, I couldn’t believe it.’

‘Harry, I’m so proud of you. You’ve worked so hard. God, I could cry,’ said Phil.

‘I hope you’re on your own. Rough tough cops can’t go around bawling you know,’ he chuckled.

‘It’s hay fever,’ Phil joked. ‘Look, I’ve got to go but bloody well done. I’ll get some beers on the way home.’

‘I’m going out with the lads to celebrate. And commiserate with the ones who didn’t make it.’

‘Well don’t be too cocky, will you?’

‘Moi? As if! See you Dad.’

‘Yep, see you and, hey, I love you.’

‘Love you, too.’

Harry pictured his dad dashing across the corridor to gush to Superintendent Gary Hedges, who would take the piss, then offer his heartfelt congratulations.

As Harry felt the tree-lined park’s soft turf cushion his feet, a lump came to his throat. It was on this very field, aged about three, that he had first dribbled a ball.

*

The watcher was only too aware that unless he kept up, it would be game over. However, fortune was smiling on him. Harry was so distracted that he’d been able to match his pace.

As Harry reached the enclosed Puppy Park, close to the woods, there were fifteen yards, twenty tops, between them. Half a dozen dog walkers were still ambling back to their cars over to the right, so pouncing here was out of the question. Witnesses were a risk and getting caught was not an option.

When they disappeared, the point of no return loomed.

Had he thought this through properly? Probably not, but he had no choice. He’d brought this on himself.

Harry disappeared into the shade of the copse. For the first time, the watcher broke into a jog. The thicket was heavy, but narrow; thirty yards and he would be back out in the open on to Woodland Way, where no doubt some Neighbourhood Watch busybody would be twitching their curtains.

It had to be now. Away from prying eyes.

Now or never.

The watcher’s focus adjusted quickly to the gloom.

Harry was still gassing.

‘Always in the bag,’ he heard him brag.

Well, you are going to be in a very different bag soon, thought the watcher.

Harry said his goodbyes.

This was it.

Pulling the red-and-black bandana over his mouth and nose, he sprung forward. ‘Oi,’ he hissed.

Harry spun round.

‘Oh hell … What the f—’ Harry blurted, his gaping eyes fixed on the glint of steel, dodging back off the path to buy some distance.

‘Shut it.’ The watcher mirrored Harry’s move.

He saw Harry was about to run, so he lunged. The blade shimmered as he thrust it forwards and up. The brief resistance offered by muscle soon gave way and the razor-sharp blade seared deep between Harry’s ribs.

Feeling the hilt snag, the watcher yanked it clear.

Harry gasped and then, holding the gaping wound, he stumbled to the ground, dropping his phone. His eyes silently pleaded for help.

The watcher turned and bolted through the bushes, the branches snagging at his clothes. In his haste he tripped on a tree root, just catching himself before he fell.

He was certain no blood had spattered, but when the cops came anyone who’d seen him flee would remember the running man. He had to get away.

Lie low.

Perhaps for ever.

Perhaps in plain sight?

*

Harry prayed it was only a punch. A hell of a punch – a hammer blow even – but a punch nonetheless. Enough to stun, but nothing too serious.

Please God.

Crumpled among the nettles and brush, hearing the crack of branches and the fading thud of footsteps as the watcher fled, he prayed he was just winded. He was going to be OK.

He grabbed his chest. What was with the wheezing? Where was this stickiness coming from? The metallic smell? It took him back to that nasty clash of heads in the Youth Cup final.

Looking down in horror, he found his hands were dripping, the greenery around him drenched in deep crimson.

He felt faint.

Every breath sapped him.

In his haze, he became strangely irritated by the nettles stinging his neck. Frantically groping the ground, he grabbed the slimy plastic of his iPhone, struggling to grip it in his blood-soaked hand. Instinctively he opened the lock screen, barely discerning the white glow.

One 9. Yes, he could do this. His life, his career, everything hung on just two more numbers.

Two 9s. One more to go.

Oh God, he was really hurting now. Feeling so weak. So alone. Fog shrouding his every sense.

Just one more. Just one more …

*

The black Audi cruised to a halt outside Carden Park, the northern outpost of Marco’s patch. Probably a customer or some busybody who’d soon get the message and piss off.

Junior swaggered up to the open car window, oozing arrogance.

Marco browsed his phone.

The piercing scream jolted him and he darted for a shadow. Had Junior been bottled? Better to watch – take it all in – than show out and put the whole crew in danger, he decided.

True horror hit him when Junior threw himself to the floor, gripping his reddening but unbroken face.

Acid.

Marco fixed on the unfolding scene; a safe – certainly not cowardly, no – distance away.

All four doors of the Audi flew open. From each sprung a black-clad bruiser, each balaclava’d up and wielding a retractable baton.

Under the orange sodium glow of the sparse street lights, the first made straight for the single gated entrance to the park, menacingly guarding the only remaining escape route.

As Junior battled to hold his melting flesh together, the other three dealers were scurrying round like ducklings separated from their mother.

Two were felled by precise knee strikes, collapsing them where they stood. Marco retched at the ear-splitting snap when metal shattered one of their forearms, offered up in hope of clemency.

The other boy quickly submitted. He and his less fortunate ally lay compliant, yet screaming, as the thugs wrenched their arms behind them and plasticuffed their wrists together. Marco was horrified as the automatic boot lid slowly raised and one of the boys was bundled in, the other manhandled into the back seat.

Marco shook in terror, forgetting his fourth dealer until he heard the desperate screams coming from his right.

He peered round a snuffed-out lamp post to glimpse the last of his gang pinned by the throat against an emerald-coloured ‘Dogs to be kept on leads’ sign. The hulk holding him produced a hunting knife from the back of his belt. The wails intensified.

He watched in horror as the man shoved the boy to the ground. As he hit the deck, the man dropped his full weight on him, knife thrust towards the boy’s pleading face.

From this distance, Marco could just pick out the boy’s petrified eyes, flicking between his attacker’s own and the knife. Surely he was not about to plunge the blade into the boy’s outstretched neck. No way would they leave a body out there in the street. Acid burns and broken bones could just about be explained away to an indifferent police force, but a body? Surely not.

The man deftly spun the lad onto his front, then flipped himself round, crushing the boy. Marco struggled to work out what was happening as the man shimmied down the pinioned body.

Clenching the boy’s calf, stopping his writhing – a futile attempt to break free – the man twisted his head round, and hissed something inaudible.

He grabbed the boy’s right ankle, stretched it a fraction, then sliced the razor-sharp blade across the taut Achilles tendon, severing it in one swipe. The whip-crack of the boy’s other ankle being bisected wasn’t quite drowned out by his screams.

The man sprung up and threw himself into the waiting Audi, which spun up Carden Avenue and away.

Marco knew he should get the hell out of there – after all, these boys could be replaced – but the begging cries from his two woefully wounded dealers tore at him. How could he abandon them? What would they do if the roles were reversed? Surely he should get help.

Then he remembered his masters’ chilling warning. Only the food mattered. Nothing else. You’ll survive any fuck-ups, but lose the drugs and you’ll pay, either in Ps or with your life.

Sobbing uncontrollably, he powered his ped away, wondering, for the first time, if he was ever going to get out of this alive.

5

7.30 a.m., Wednesday 2nd May

Detective Superintendent Joanne Howe had managed to get to work early for a change. Life was tough while Darren was away, but she still felt guilty asking for help with the boys. Few blokes would have such qualms.

Like every other department head, she had to find savings – cuts in the midst of an unyielding tsunami of violent crime. She’d grabbed a desk at the Crowhurst Road police station, next to the custody block, and pored over spreadsheets and pie charts willing for the answer to appear as if from a Magic Eye picture.

The blast of her Eddy Grant ringtone came almost as a relief.

‘Morning ma’am.’ She hated ‘ma’am’. It was so dated. ‘It’s the control room. The Brighton duty inspector asked me to give you a call. A runner phoned in about half an hour ago to say she had found a body in Withdean Park woods. We’ve got officers out there and they’re asking for you.’

‘Me specifically? Have you tried the on-call SIO? It’s DCI Scott Porter this week.’

‘Yes, but there’s a massive pile-up on the M25. He’s got no hope of getting here from Kent much before ten o’clock. You’re the nearest I’m afraid.’

Jo cursed. This was happening time and time again. It was bad enough when the Major Crime Unit comprised just Surrey and Sussex, but since they took in Kent and Hampshire, most of her officers were spending at least four hours a day on the road. And when this ate into the Golden Hour – the time during which finding and securing evidence was most crucial – killers were literally getting away with murder.

‘Right, tell me what you’ve got and I’ll get there as soon as I can.’

The controller read over everything he knew. Jo then reeled off a list of instructions and made him repeat them back, before grabbing her go-bag and car keys, glad to leave the number-crunching until later.

*

Phil’s guilt at leaving Ruth tortured him as he abandoned his car at the back of Brighton Police Station. While neither mentioned it, both knew she was dying. Her determination to do so at home, surrounded by those she loved and memories of happier times, was all that mattered.

There was never a good time to leave for work early but, if Phil was to be with her tomorrow when the Macmillan nurses would doubtless broach ‘end of life pathways’, he needed to make a dent in the shedload of reports, authorisations and whatever other unread tedium was clogging up his inbox.

If only the boys had woken up to take over when he left. Gone were the days when he could waltz into their rooms and demand they get their act together. Nowadays he risked stumbling on a scene that no dad should see. They were eighteen and twenty, after all. He wanted them at home for as long as possible, so if they brought a girl, or in Kyle’s case a boy, back – so what? He’d rather that than force them into dossing in some shitty drug-infested bedsit, as so many of their mates did.

As he swiped his access card across the reader, his phone chirped a text.

This is your early warning system!! The Chief is in your office. Been found out after all these years??!! Lol. Gary.

Shit. Helen Ricks was not a time-waster, but she liked to make the most of her visits to divisions, ‘to see the whole coalface’. He would try to fob her off and on to Gary, but knowing that wily git he would have already conjured up some non-existent gold planning meeting or safety advisory group that he couldn’t possibly miss.

Plodding up the stairs, frantically trying to plot a credible exit strategy, he nodded and grunted good mornings to the exhausted cops and civilian staff he passed.

The chief constable, he saw, had already made herself at home at his small circular conference table, tapping furiously away at her laptop.

‘Oh, morning ma’am,’ said Phil, feigning surprise. The steaming cup of coffee next to her made him wonder whether Gary had threatened to gob in hers as well.

‘Just a minute, Philip,’ she said, waving a hand but not looking up. ‘I just need to reply to the PCC. She’s on my back again, which is what I want to talk to you about.’

‘Sounds ominous,’ said Phil, trying to affect nonchalance.

He slipped off his civvy jacket and, as he hung it on the coat stand, he glimpsed Gary in his office opposite, grinning. His pumped biceps jumped as he mocked hanging from a noose.

*

Jo and Crime Scene Manager Dean Gartrell listened as the uniformed sergeant briefed them by the fluttering blue-and-white police tape.

A couple of clarification questions later and they both struggled into their ‘one-size-fits-no-one’ forensic barrier suits, gloves, masks and overshoes.

Dean held the tape up for Jo to duck under, then they edged their way towards the wood, the grisly tableau emerging into view.

The canopy of trees eclipsed the early morning sun and they inched into its shade, balancing on the steel stepping-plates laid out. On reaching the red-and-white tape that marked the inner cordon, the kernel of the scene, they silently peered at the horror before them.

The blood-soaked corpse lay flat on its back on a bed of ruddied nettles and bracken, eyes still agape in shock. The reek of decomposition had yet to take hold; the only aroma was the perfume of fresh vegetation tainted with the ferrous, slightly sweet, tang of spilt blood.

The chaffinches high in the trees chirped their mockery at the butchery below.

An explosion of red rendered the corpse’s Brighton and Hove Albion tracksuit top barely recognisable. The phone resting beside the open left hand would no doubt hold clues but the foliage, the post-mortem and, God willing, witnesses would be the key to this senseless death.

Jo crouched for a closer look. She studied the cadaver, then sprung up.

Something about the boy’s features. In death, people looked different – pasty and drawn, all colour and structure stripped away – but she was sure she had seen him before.

‘Dean, do you recognise him?’

They squatted together, Dean’s hood and mask hiding his furrowed brow.

‘I don’t think so. It’s hard to tell.’

She remained on her haunches, her tilting head in deep thought.

‘Look closer.’

Dean studied the body from a different angle. Jo watched him in reverential silence as her worst fears swelled.

Someone shut those bloody birds up.

Jo expected him to stretch back up, with either a name or a blank look but, eerily, he remained rooted to the spot.

‘Any clue?’

He stood up slowly. Pensive.

‘I didn’t notice before.’

A deep foreboding swelled deep in Jo’s stomach; the gut feeling that this was surging from tragic to catastrophic.

‘Well?’

‘I can’t be sure, but he looks so familiar and, of course, the tracksuit …’

Jo offered up a name, her voice trembling.

‘I think so.’

‘Think?’

‘No, I’m sure.’

Jo nodded, dreading where her next stop must be. He had broken her heart once before, but that was nothing compared to what she was about to do to him.

*

Jo drove to the police station in a blur. She should have been planning how to break the news but instead her thoughts were swamped with headier days.

Was it really fifteen years ago? She was Jo Reed then, young, free and single, but that was no excuse. How often had more worldly-wise women on the force warned her against the charms of the senior men? How often had she promised herself she was not that kind of girl?

She had always been cautious after what had happened to her sister, but common sense gave way to lust that night.

It was supposed to have been a quick overnight stay while her and DI Phil Cooke spent two days debriefing a prisoner in Norwich Prison, all in preparation for taking down a vicious crime family – the Larbies – that had the south coast’s drug market all sewn up.

The pre-dinner drinks, the bottle of Greek red with their kleftiko, moussaka and then their nightcaps were no excuse for what happened.

She had always found him charming – a bit rough around the edges – but a true gent to her and the young DCs under his command. Off duty though, she found him beguiling, funny, self-effacing and, above all, truly interested in her. Not all ‘me, me, me’.

The peck on the cheek that should have sent them to their separate rooms became a lingering kiss and before long they were naked in each other’s arms on the ‘sleep guaranteed’ king-sized bed. The hotel did not live up to its promises that night.

In the morning, as she watched the rise and fall of his honed chest – damned fit for an older bloke – she wanted to feel guilty. He was married, had young kids for God’s sake, but her heart ached for this not to be a one-night stand. She’d always baulked at the notion of love at first sight, and this was not first sight by any stretch of the imagination, but something had happened. It was so wrong but felt so right.

The following morning, Phil stretched the enquiries out a couple more days – ‘to follow up on some local leads’. In fairness there were more people to see but, aside from that, they hardly left her bedroom over the next forty-eight hours.

The flame of their six-month affair – and plenty more ‘overnight work trips’ – with all its secrets, betrayals and passion was ignited in that Best Western anonymity.

*

Nailing the clock above the door was one of Phil’s first acts as divisional commander.

That way, with just a flick of his eyes he could gauge when his visitors had outstayed their welcome – provided he could bag the seat opposite.

Unfortunately, Chief Constable Helen Ricks knew his ploy and had got in first, leaving Phil to only guess the time. He had no idea how long she had been droning on, but could see his day spiralling down the drain.

‘So you see, Philip, it’s all about innovation. We can ill afford to have another attack. Certain people are getting jumpy and it’s all coming back to you – and me.’

‘But I can’t get blood out of a stone, ma’am,’ pleaded Phil. ‘Of course, we would love to do things the way we used to, but the troops have hardly come on duty before they’re swallowed up by the vacuum created by the previous understaffed shift. It’s a vicious circle.’

‘I know, but you need to work with others. The council, schools, youth groups, private businesses. Anyone. We need to stop crime before it starts.’

‘So, can I assume that I can ignore ACC Acers’ demands for another pound of flesh?’

‘Leave Stuart to me, but try to be positive.’

He was about to argue, but was saved by a sharp rap on the door. Phil looked at the chief and on her assenting nod he said, ‘Come in.’

Superintendent Gary Hedges opened the door, but rather than bowling in as was his habit, he hovered in the threshold avoiding eye contact.

‘What is it, Gary?’ demanded Phil.

‘Ma’am, can I have a word please?’ he said.

‘Say whatever it is in front of me,’ Phil chuckled. ‘Last time I checked I was still the divisional commander.’

‘Ma’am?’ pleaded Gary.

Helen Ricks shrugged, stood and walked towards the door. ‘I won’t be long.’

Fear swamped Phil. Was it Ruth? He checked his phone. No missed calls.

Anger took over. He sprung to his feet. No one kept secrets from him, not on his patch, not even the chief bloody constable.

As he stepped into the corridor, a gentle but firm hand clutched his right arm.

He spun round about to unleash a tirade, catching himself just in time as a familiar but tortured face stared at him. He read the signs straight away. Softly she guided him back through his door, saying nothing.

‘Jo, what is it? You’re scaring me.’

‘Phil, please sit down,’ said Jo as she eased the door closed.

He moved round the conference table to his favoured chair, his stomach clenched, eyes searching Jo’s face for clues, but at the same time praying he’d read this wrong.

Whenever he was about to destroy a family with the worst news imaginable, they always knew – even before he had opened his mouth.

He knew.

Jo sat opposite, her slender features strained. She reached for his hand, but he snatched it away. He needed to take whatever was coming straight.

‘Phil, I don’t know if you’ve been told, but early this morning a runner found a body in Withdean Park.’

‘Gary is duty command. Perhaps he knows,’ he quaked. Make this go away.

Jo faltered. Her gaze dropped.