Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

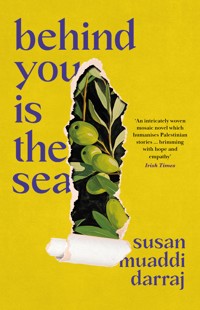

Behind You Is the Sea is a compelling debut that fearlessly challenges stereotypes surrounding Palestinian culture. 'Intergenerational differences … are explored from both sides with keen-eyed humanity and understanding' Marie Claire 'Funny and beautifully written' Stylist Magazine 'A rich panoply of a community'Crack Magazine Book of the Month 'Wonderful … A novel about ordinary people fighting for what they believe to be right' Irish Independent 'A poignant reminder of our shared humanity … brimming with hope and empathy' Irish Times Funny and touching, Behind You Is the Sea brings us into the homes and lives of three main families – the Baladis, the Salamehs and the Ammars – Palestinian immigrants who've all found a different welcome in America. Their various fates and struggles cause their community dynamic to sizzle and sometimes explode, as their lives intersect across divides of class, generation and religion.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 280

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

BEHIND YOUIS THE SEA

SWIFT PRESS

First published in Great Britain by Swift Press 2024

First published in the United States of America by HarperCollins Publishers 2024

Copyright © Susan Muaddi Darraj

The right of Susan Muaddi Darraj to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Thank you to World Literature Today and Red Hen Press for allowing us to use the words of Ibrahim Nasrallah and Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, respectively.

Designed by Ad Librum

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781800754171

eISBN: 9781800754188

To my children,Mariam, George, and Gabriel

You have to be loyal to your exile as much as you are loyal to your homeland.

—Ibrahim Nasrallah

if all that breaks our hearts is

yesterday,

and the silent colonnade

anticipating

the dynamite,

if all we love

is a lost world

then let the dust

swallow our names

let the maps

beneath our feet

burn.

If all we are is past,

who are these millions

now

gasping for air?

—Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, “Ruin”

Contents

A Child of Air

Ride Along

Mr. Ammar Gets Drunk at the Wedding

The Hashtag

Behind You Is the Sea

Gyroscopes

Cleaning Lentils

Worry Beads

Escorting the Body

Acknowledgments

A Note from the Cover Designer

A Child of Air

Reema Baladi

Amal calls it “the thing” too, but I hear she’s getting rid of hers. Her brother is a cop and he’s planning to find the money somewhere. Torrey says he’s probably running drugs like the other crook cops do. Marcus isn’t one of those. We all grew up together, I tell Torrey, and Marcus is solid. Torrey is trying to get me the money to get rid of it too, but here’s the other thing I have to tell him: even if I had the money, I’m keeping mine.

What Torrey doesn’t get . . . what nobody gets . . . is this is the best thing that’s happened to me.

Torrey’s not bad. It’s just he’s been here before, in this situation. One girl he got into trouble was Tima, who rents a room in a house near Hopkins, and she went during week twelve, okay, week twelve, to take care of it. It happened with some girl from Dundalk too, he said, but she didn’t want to see him so he just sent her the money, a wad of fifties, with his friend.

He doesn’t want to get married or anything, and since my father is dying, it doesn’t matter anyway. Amal’s father is all strict, but mine is sick, and having a sick father exempts you from most Arab rules.

Here’s how it is with us: usually your mom also keeps you in line, to make sure you do your duty: grow up slim and gorgeous so you can be a doctor’s wife, get your nails done every week, and have a cleaning service. Amal and I both got skipped when they handed out tough moms, but not because we’re lucky or anything: Amal’s died a long time ago, and my own mom is like a ghost. Like when I told Mama about the thing, she just looked at me with her phantom stare, like I wasn’t even standing in front of her. She spends all day either praying for Baba or scrubbing invisible stains out of the linoleum floor. A lot of times, especially lately since he’s worse, I find her with her elbows propped on a pillow at the windowsill, looking down on Wolfe Street and watching everyone else live.

“Your mom is nuts,” Torrey says one day, after I told him I’m thinking of keeping it and maybe she can help after it’s born.

“So?” See, I don’t even deny it.

“Just telling you how it is. She can’t take care of herself but you want her to take care of my baby.”

“No, I want her to take care of my baby.”

“Come on, Reema. She’s crazy.”

“The whole block says the same thing. You think I care what they think?”

“How ’bout me?”

“Oh? You?” I say, all tough. “I don’t give two fucks what you think.”

He stares at me when I talk shit like that, and then he gets a big smile over his face and usually ends up kissing me. He does that now, and he did it when we first met too.

I was working at the Aladdin restaurant and qahwah, owned by Mr. Naguib, but everyone calls him al-Atrash because he’s deaf. He’s from the same village as my parents, Tel al-Hilou, and Baba used to do odd jobs for him; that’s why he hired me, when he heard Baba’s cancer was back with a vengeance.

It was good for me that al-Atrash couldn’t hear anything because that meant I answered all the phone calls and took reservations. Torrey used to hang out at the deli next door and he’d walk by to check me out. Sometimes to wave. Sometimes he would pretend to ignore me but just stand there, posing in his tight jeans and denim jacket. I would stand at the desk by the front door, and there was a big picture of some sultan-looking dude on the wall behind me. Some ugly-as-fuck velvet picture that al-Atrash found at a yard sale in Canton.

One day, Torrey stood by the door and winked at me.

I rolled my eyes and turned my back.

The phone rang. “Why you can’t even smile, girl?” he said, and I whipped around to see his face near the glass, his ear pressed to his cell phone, his grin so damn big and corny.

He’d call all the time after that. He’d sing that Groove Theory song to me that I liked, especially that line: “‘You’re so lovely when you’re laughing,’” he’d sing in his deep voice. “‘It makes my day to see you smile.’” Over and over. Sometimes he’d call and just sing it to me, that one line, watch me to make sure I smiled, then hang up. A lot of times, while we snuggled after, he’d tell me all the people he thought I looked like, and one of them was Amel Larrieux, and that made me happy because she is so beautiful.

Torrey was the first person in my life to ever tell me I was beautiful. I mean, he’s mad because I’m not listening to him right now, but in some ways, he is dedicated. He called me “baby girl” even though he’s only two years older than me, but because I’m still in high school, he thinks he’s an adult and I’m not. If he’d known back then how I was the one dealing with Baba’s sickness, with Mama being a phantom, and even with taking care of my baby sister . . . he’d know for sure I was a grown-ass adult.

The first time we went out, I lied to Mama and said I had to work late. She never talked to al-Atrash herself, she never talked to anyone really, and Baba was so sick by then anyway. All he did was lie in bed and gasp when the pain would set in, sweating and sucking in his breath so sharp until Mama gave him the pills. Those things just knocked him out, as far as I could tell, and even though I was glad he wasn’t in pain, I missed him. I felt bad lying to Mama, but it was so easy to do. Baba never let me out, but now that he didn’t know me from my little sister, I figured this was what they call a silver lining. Mr. Donaldson in English class said that all the time: “If there is a silver lining to the death of Romeo and Juliet, it’s that their families realize the error of their ways.” Not sure about that, I remember thinking. Fuck their families, honestly.

So, that first date. Torrey walked me to the Burger King on Greenmount. I just ate small fries so he didn’t think I was a heifer plus I had no clue if he was going to pay for me. How would I know? I told him I had to be home by nine—that’s what time I would normally be home anyway, if I was working at Aladdin. Mama didn’t ask a lot of questions, even of the home nurse who came on Fridays—she just absorbed whatever you said and didn’t comment. Didn’t repeat anything. When Mrs. Miranda from down the block asks me why my mom doesn’t talk to her—“What, she don’t like me or something?”—I tell her she doesn’t even talk to me so don’t take it personal.

“You live where?” Torrey asked me, as he bit into a Whopper. He had three lined up in front of him.

“On Wolfe,” I said, delicately dipping a fry into the ketchup, trying to be cool.

“Your family?”

“What about them?”

“Got one?”

“Yeah.”

“Do I gotta worry about your dad showing up here or something? I heard about you Arab girls.”

I asked him if Puerto Rican fathers are any different, and he grinned and took another bite.

Sometimes in school, I can turn on a different Reema. I can be someone else when I’m taking a test. It always makes my teachers wonder if I’m somehow cheating. But it’s just that I’m good at putting on a show. In that moment, with Torrey, I put on a show. I shrugged and said no like he was an idiot. And it worked. He smiled and we talked about other things: how al-Atrash is probably a racist because he doesn’t like it when Torrey and his friends hang out in front of Aladdin’s; how he was taking a class at a time at the community college but would probably drop it because of the money; how he was thinking about joining the military but really hated guns and the thought of killing other brown people. “I’m like Muhammad Ali, you know?” he said, laughing. “For real, though. I’m not gonna let them trick me into fighting some war, just so they can pay for classes and textbooks.”

We did that, me and Torrey, a few times—eat at Burger King (he always paid) then make out in his car. He tried a lot of times before I had sex with him. I told him I never did it before, and he smiled that charming smile and promised he’d do all the work. He joked a lot like that, to make me relax. And the first time was really nice. That’s why I kept going back, even though he didn’t wear a condom. “I’ll pull out,” he promised coaxingly. “I know, baby girl . . . I know what I’m doing.” And because I didn’t, I stayed quiet.

He was gorgeous, I thought that even then, and his eyes were green. They stood out like emeralds in his brown face. That, plus the curly hair on top of that head? I was gone. I would have lied to Mama a thousand times just to be with him again.

And now we’re here.

Now he wants me to do what Amal is doing, and he’s mad because I’m being stubborn. “I have zero dollars,” he says. “Nothing. And I’m not going to marry you.” He doesn’t say this mean, just matter-of-fact. I know he’s not with anyone else, because his friends tell me how he’s obsessed with me, plus he calls me constantly. He has a beeper, so if I call it, my own phone rings within seconds. He even comes to the doctor with me, because I figured out how to get checkups without Mama knowing a thing.

“This is wild,” he says, looking at a poster of a growing fetus in the womb. And when the doctor hands him the stethoscope and he hears the heartbeat, he bursts into tears.

Baba is getting worse, the nurse says. She talks to me sometimes because she doesn’t think Mama understands her.

“She understands you,” I tell her, “but she doesn’t know what to really say.”

“He has about a week,” she says, patting my shoulder with large, strong hands. “I’m going to make him as comfortable as I can.”

Comfortable means pain-free, which also means he’s already dead to me. He won’t hear me if he’s drugged up. His eyes stay open, so I surround him with books and pictures. The books are the Arabic books he likes to read, their pages thumbed and worn down so much that you can run your finger down the side and not get a paper cut. Some of them are Arabic language workbooks. He used the same books over and over when he was teaching me how to read Arabic. I wasn’t allowed just to learn the dialect we spoke . . . I had to study the fus-ha Arabic, the hardcore, classical Arabic that they use only in fancy speeches and news talk shows.

He spent a long time teaching me how to read and write, how to connect the letters together because Arabic is not printed. The letters mostly slide into each other. Except for some letters—some letters, like ra, alif, and others—are complex because they don’t want to be connected. They’d rather cut a word in half than reach out and link to the next letter. My name is like that—the first letter is ra, and it’s separate from every other letter in my name. Sometimes, when Baba would make me write it over and over, I imagined that the ra was standing on an island, cast away from the other letters, watching as they sailed away together.

I put two small tables on either side of him and prop up pictures of me carrying Maysoon, who is two years old and has no clue what’s happening. I add his wedding photo, which makes me sad because he and Mama are so young, about to board a plane from Palestine to come to America, and they look so hopeful. They have no idea what’s coming.

There’s one picture of when he came with me to the middle school play and someone snapped a pic of him with his arm around me. I’m in my Nutcracker costume—the only fairy with black hair and thick thighs and tits in a sea of skinny blonds, but I thought I looked pretty good and Baba told me that night, as he watched me onstage, that he thought I would fly.

It’s a special picture because it’s the only one, really. Not the only picture, I mean—the only “moment.” He didn’t come to my stuff a lot. He worked all the time. He worked for al-Atrash. He worked for Mr. Ammar in his strip mall, doing odd jobs: painting parking lot lines and speed bumps, cleaning the siding, installing new doors. He worked in the Thai restaurant down the block, washing dishes, making six dollars an hour. He saved some money for me to go to college, I tell Torrey, despite all this. He still saved . . . which I cannot believe. He saved it for me, and told me one day he needed me to find good work and save it for my little sister. He would help me, but I would have to help Maysoon. He couldn’t do it for us both.

In English class, we’re getting ready for the AP exam in May, months away. As far as I can figure, if I keep it, I won’t be taking that exam at all. But I prep for it anyway. Our class is small, about fifteen kids, and Mr. Donaldson makes us practice by writing short-answer responses to specific questions. I usually do well on them because I always know to “back up what you say.” If you say, “The poet has an ambivalent attitude towards death,” you must back that shit up with evidence.

But today, I’m not ready. Mr. Donaldson gives us a Robert Louis Stevenson poem, “To Any Reader.” I’m into it from the beginning. That’s never the problem. I read really well—English and Arabic—so my comprehension is like nothing you’ve seen. But this poem . . . the ending is what gets me: “It is but a child of air / That lingers in the garden there.”

I don’t write a word. I just think of all the sadness that’s suddenly in my heart. How can one line, “a child of air,” do that to you? It’s not what the poet meant, for sure. But I’m taking it that way. Because that’s what is at stake here. I don’t want to be haunted by a child of air. My mother is already made of air. My father is basically gone.

Torrey? Torrey loves me. But I know better than to depend on anyone like that.

I take a zero on the writing and avoid Mr. Donaldson’s eyes.

When I walk home, I think about the craving I have inside of me. It’s like an empty spot that I can never fill. I pause at the crosswalk, watching the cars zip by. Instead of crossing the street, I turn back and make a right on Mitchell, towards Amal’s house. The other Arab girls at school have been talking about her. Even though she’s in the same situation I’m in, I haven’t talked to her in so long. It bothers me to hear what they say, because they are worse than white girls in some ways. Their dads are the type who were already doctors and lawyers when they left Palestine. Or they had money and came here and started buying up shit. Mr. Ammar is like that, a real estate type. He owns the strip mall that Aladdin’s is in.

Amal and I were always friends, maybe because our dads are the type who work for their dads. When you’re at the bottom, you stick together.

I know their house by the large metal frame on the side, with a grapevine snaking around the poles. When my mother was normal, and when Marcus and Amal’s mother was alive, they used to pick the leaves. Every weekend in June—that’s what they did. And they’d clean the leaves and dry them and flatten them in Ziplocs and put them in the freezer so we could eat fresh warak all year and not the salty stuff in the jars. Now it looks like a jungle. The leaves have not been picked and they grow wild—I can see them creeping into the neighbor’s lawn, over the fence, looking for more room to stretch.

Marcus, Amal’s older brother, is in front of the house, trimming the shrubs under the window with big clippers. I’ve always had a crush on him, honestly. He looks like the painting of Lord Byron we saw in our English textbook— slick black hair and big eyes.

“Hey, runt,” he says and grins. “Long time.”

“How’s everyone?”

“Eh. Okay. How’s your dad?”

“Same.”

“Did they say—”

“Any day. They said any day.”

“Hey, you have my cell, right? You call me anytime, okay? You or your mom.”

I say thanks and ask about Amal, and he gets weird on me. I finally get him to crack a bit, and he tells me Amal is not living there anymore. “You know how my dad is,” he says, sighing. He makes a big deal about a small twig sticking out of the shrub and he surrounds it with his clippers, then decapitates it. “He’s so goddamn stubborn.”

We stand there for a bit, until I say, “I mean, is she okay?”

“She’s okay. It was the right thing,” he says. “I don’t care what anyone else thinks, you know?”

“Yeah. Me neither.”

I tell him I’m going home now because I have to work at Aladdin’s tonight. He jokes that he better not see me smoking narghile with the old men when he swings by. “Hey, runt,” he calls out as I walk away. “You call, okay?”

“I will.”

The day he dies, Baba looks skinny and surprised. When he sucks in the last breath, his mouth opens in an O, like America has shocked him at last, and freezes there. It’s like he finally understood he was never meant to win here.

We’d known it was coming. You can tell. You don’t even need anyone to tell you that all you have left are just a few minutes to be together, intact, as a family. So we stood around him, me, Mama, and Maysoon. The nurse with the long gray hair asked if we should call someone else, but there is no one. She stayed in the next room, to give us privacy while we waited, but she came in whenever she heard him gasp or to put more morphine in his IV. “He can hear you,” she reminded us every time before slipping away again.

Americans like to talk about everything, I know. They like to share their feelings, like purging old clothing or dumping clutter. But when you’re like us, you purge nothing. You recycle or repurpose every damn thing. Nothing is clutter. And as I stand here, watching my father die before he ever really lived, all I can think about is how I’m going to use these feelings I’m having now. I need someone to love, the way I love Baba. I can’t love Mama because she’s a ghost, and my sister is so young that . . . well, I can love her, but she may not always want it from me. Torrey is someone I can love, but he may not always be able to give it back, either. Not with the steadiness I need.

While we wait for the doctor to come in and confirm time of death, I go out and talk to the nurse. She’s sitting quietly, her hands folded in her lap, and I wonder if she’s praying for us. Deep inside, I hope she is.

I need to call someone after all, I say. Two people, in fact. First, Marcus, because he knows how to handle these things. He will come here, he will tell us what to do next, and he will tell all the other Arabs the news. Then Torrey, to tell him, with my hand on my belly, I’ve decided where I’m going to pour all this love that’s dammed up in my heart.

I miss the AP exam. I decide I’ll save the money that Baba left for Maysoon’s education instead—she might use it someday. Torrey is getting more and more used to the idea that he will be a father, whether he wants to be or not. But he surprises me because he’s less and less mad. Sometimes, he puts his palm on my belly and waits there, looking like a child himself.

When the baby is born, Torrey tells me I can choose the name. I tell him of course I can—it’s not like he’s doing me a favor. I’m going to name him after my father, I explain. I’m the daughter, but my son will have my father’s name anyway.

“What’s your father’s name?”

“Jibril.”

“What’s that mean?” he asks, though I can tell he likes the way it sounds, the softness, the strength of it.

“It’s Arabic for Gabriel.” I write it out for him in Arabic, and I show him how the ra in the middle of the word doesn’t get connected to the other letters. “Like my name. His name is like my name that way.”

“Jibril. Gabriel. Jibril.” He sounds them out, slowly, tenderly. “Oh yeah,” he says, smiling. “I like it, baby girl.”

“I don’t care if you do.”

“But, baby girl? I do.”

He squeezes my hand and I accept that quietly, my heart trembling but ready.

Ride Along

Marcus Salameh

My sister is on a ride along with me, buckled up in the backseat, when she tells me about her boyfriend, Jahron. I’m turning left onto Curry Avenue because they’ve just called in a disturbance at the Overlook Townhouses. Domestic.

“He’s sweet,” Amal says, her black eyes wide in her milky face. They fill up my rearview mirror. We bring civilians along all the time, and she’s technically allowed to sit up front with me, but I don’t tell her that. Instead I tell her it’s regulation, that she’ll be safer in the back.

“Wife says husband’s hitting her. There’s a four-year-old boy in the house. She says he’s also been hit,” comes Gerard’s voice over on my radio.

“Car Four Fifty, en route. Three blocks away,” I respond, then shut off my radio. “Go ahead,” I tell Amal. “Your friend. Tell me about him.”

“When I graduate, it’ll be because of him, you know.”

“Oh yeah?” I go right on Taunton Avenue and look for number 225.

“He tutored me through all my English classes. He’s the one who thought history was a good major for me.”

“Nice.” Here I’m thinking that I was the reason she’d graduate, seeing that I’d paid most of her tuition bills the last four years.

I find the house, a two-story with a fake well on the lawn. I hate those things, especially when they have the fake bucket hanging on the side. Like anyone’s going to believe this family hauls water out of the ground when, if you just look up, the electric box is sticking out of the side wall and the AC unit is tucked in by the back fence. Baba has one too, except his is even worse—it’s got those plastic flowers from the dollar store planted inside with rubber dirt. A fake well that’s being used as a flowerpot. For fake flowers.

Lights are on in the front window. Upstairs is dark.

“Marcus? Should I stay here?” Amal asks timidly. I hate when she says anything timidly. Makes me want to remind her who she is.

“Yeah. Keep the windows up and the doors locked.” I get out and walk up the driveway, where tufts of grass grow disobediently around flat round stones like they enjoy breaking the rules. My eyes sweep around and up and down the street. Upstairs. Downstairs. It’s quiet and I don’t like it.

I knock three times, hard, and the front door opens. Blond with a red, puffy face. Red eyes. “It’s okay. I’m okay,” she mutters. Her face and chest are dotted with sunspots. They’re even on her arm and the hand that holds open the screen door. The other hand is down at her side, behind her ass.

I show her the badge and tell her we received a call. “I need to see your hands, ma’am,” I say, and she pulls out her hand quickly, then hides it again.

“We’re really okay,” she says again.

“Well, I still need to ask you some questions,” I say and smile. “They make me ask, since you did call. Sorry.”

She nods nervously, looking over her shoulder.

“Are your husband and child home?”

“Oh yes, we’re all watching the O’s game. It was just stupid, a misunderstanding . . .”

“Oh yeah? They playing the Blue Jays?” She’s distracted because I hold out my badge again. “Here, look at it.”

“Yeah, the Blue Jays. Listen, okay, it’s fine . . .”

“You should check it out, you know. I’m driving an unmarked car. I could be anybody.” I hold it out, waiting pointedly, wearing a smile.

She rolls her eyes and takes it with the other hand, the one behind her. It’s quick—she grabs the badge, flips it over politely, and gives it right back, but I have a few extra seconds this time to see what I need to see. The blue bruise around the wrist, the long scratch along the forearm, the bruise above the elbow where she’s been grabbed.

“Who’s winning?” I ask, now that she’s comfortable. “The Blue Jays?”

“Yeah, the Blue Jays,” she says. “Well, thank you. Sorry you had to come out for nothing.”

“So, actually, the O’s are playing the Yankees tonight,” I say, stepping into the doorframe. “And I’m going to need to see your son.”

Later, at the station, Amal watches me book Mr. Alex Joaquin IV—and he insists that I call him “the fourth”—for second-degree assault, while his wife curses me the whole time. “He didn’t do nothing!” she shrieks the whole time, telling everyone: me, my captain, the wall. “I told you.”

“Your son had a bloody nose,” I tell her as calmly as I can because people like this really piss me off. She shrieks again and I try to tell her quietly there are people who can help her, numbers she can call. She refuses to take the social services card I try to press into her hand.

As I drive Amal back home to her apartment, she asks me what will happen to the boy. I tell her they’ll start a file, watch the family to make sure he’s okay living with the mother. She looks sad, tiny in the backseat, her frizzy hair stuck to her temple like spider legs. “Hey,” I say, “finish telling me about your friend.”

She perks up and leans forward. “Marcus, I want you to meet him. And maybe sometime soon I can introduce him to Baba. You know, he wants to meet my family . . . he’s been asking.” My poor sister.

“I’d like to meet him,” I say.

“Thanks, Marcus. Hey, how about you?” she asks. “You seeing anyone?”

“Nobody special.”

She leans back and sighs. “You’re lying,” she says.

The next day I drop off my father’s groceries. Baba lives alone in the house. It’s been fourteen years since my mother died. He’s changed nothing, really, except to take down all the photos of Amal and hang up my picture—the one from the police academy—in the living room. It’s my best photo, in the uniform. I’ve got my first medal on, my eyebrows and sideburns are still black. Can you believe that I used to get this paint that you comb in your hair, and you know I used it on my eyebrows. Yes, sir. If my mom were still alive, I would ask her to do it for me. I would ask Michelle, but she would just give me a weird look and accuse me of being a girl. But I’m not being a girl. It’s just that it’s wrong for a thirty-eightyear-old man to have white hair.

Baba comments on it every time I see him. “You getting old. You need to get married.” But I ignore him every time he says it because if there is anything he hates more than Benjamin Netanyahu, it’s Michelle Santangelo. Today, I walk in and set the bags on the counter and unpack: cans of chickpeas, cans of red kidney beans, bags of bread, so much bread. The man eats three bags of it a week but he’s still as lean as my nightstick. Just as leathery too, because he still smokes a pack and a half a day and is always pissed because it’s something I refuse to buy for him. “Wallah, I pay you back, ya kelb,” he argues, but it’s not the point and he knows it, and calling me a dog won’t intimidate me, not the day after an abuse victim called me the asshole.

“You want the milk upstairs or down?” I ask.

“Down,” he says from his favorite spot on the kitchen stool, where he’s busy puffing away and reading the Jerusalem Times on his iPad, which is really my old iPad. One of his Umm Kulthum tapes plays in the old boom box, which was mine when I was in high school. “What the hell Abu Mazen is doing?” he mutters but he’s not really digging for an answer, not from me, because I’ve never been to Palestine. We never had the money growing up, and Baba stopped talking about it after Mama died.

I head downstairs, to the second fridge. When I was a kid, my mother bought a used fridge-freezer and kept it in the basement to store extra food. My mom was a wizard shopper. “Look, ya Marcus,” she’d say, pointing to the register before handing over her coupons. And the subtraction would start: “Two dollars off two, one dollar off one—but double the coupons, Marcus.” And I’d watch eighty-nine dollars wither down to forty. “That’s why I love this country,” she’d say, and the cashier would laugh every time. She knew them all on a first-name basis, asked about their grandkids, their bad backs, their knee surgeries, told them how lovely their hair looked. “I have a lot to learn from you,” one of them, a middle-aged white lady with red hair, always told her when she ripped her receipt off the printer.

That fridge was one of the hardest-working things in our little house. When Mama cooked, she cooked enough to feed all of Ramallah and Baltimore combined.

“You know, you have a whole bag of baby carrots down here!” I yell up at Baba.

“On the top shelf?” he calls down.

“Yeah.”

“In the big bag?”

“Yeah.”

“It’s unopened?”

“Yes! They’re here!”

“I know. Leave them there.”

“You old bastard,” I mutter and run upstairs. He’s still on his stool, by the window, the morning sun shining through the two broken blinds and off his clean, bald head. He’s wearing his brown cardigan, the one my mother knitted for him more than twenty Christmases ago, and it’s held up all these years. He keeps his Lucky Strikes and lighter in the left pocket, his tissues and the remote control in the right. He wears leather loafers with white sport ankle socks.

“Marcus, you have work today?”

“At four. Till two.”

“Too late for you, no?”

“It’s fine.” And then I just dive into it. “I saw Amal last night. She came with me to work.”