Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Little Tiger Press

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

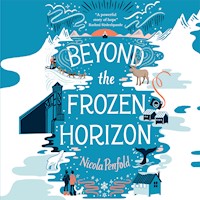

The earth is thriving – with wilderness status protecting land and wildlife, and scientific organisations researching new ways to support human life sustainably. Rory's mum is a geologist on one of these projects, and Rory is beyond excited to join her on a work trip to the Arctic. But the project isn't all that it seems, and Rory soon learns what's at stake for the people and animals who live there…A thrilling and thought-provoking ecological adventure from the author of the highly acclaimed WHERE THE WORLD TURNS WILD and BETWEEN SEA AND SKY. Perfect for fans of THE EXPLORER, THE LAST WILD and WHERE THE RIVER RUNS GOLD.PRAISE FOR BETWEEN SEA AND SKY:"Atmospheric, memorable, extraordinarily gripping, this is storytelling at its finest." – The Guardian"I loved Penfold's debut … and this confirms her as a rising star of children's fiction, mixing a thrilling evocative adventure with pertinent themes of the environment and recovery." – Fiona Noble, The Bookseller "A beautifully told adventure that will have readers, like its protagonists, diving deep to discover the fragility of our eco-system and emerging emboldened to protect its delicate balance." – Sita Brahmachari, author of Where the River Runs Gold"A message to us all in the most powerful, evocative and hopeful story spinning." – Hilary McKay, author of The Skylarks' War"I loved Between Sea and Sky. I was totally immersed… I could almost smell the sea and feel salt in my hair. Powerful storytelling and a thought-provoking tale." – Gill Lewis, author of Sky Hawk"A shimmering testament to the restorative power of nature and the limitless wonder unearthed by childhood curiosity." – Piers Torday, author of The Last Wild"BOSS level MG dystopia, so vivid!" - Louie Stowell, author of The Dragon in the Library"Nicola Penfold makes me want to love our planet harder, hold it closer." – Rashmi Sirdeshpande, author of How to Change the World"This is compelling, high-stakes storytelling… This will be a favourite that I will return to over and over again." – Nizrana Farook, author of The Girl Who Stole an Elephant"An original and wonderful story of wild children and a world in trouble … so perfectly written that reading it is living it. And living it is an adventure." – Rachel Delahaye, author of Mort the Meek

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 300

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Praise forBeyond the Frozen Horizon

“Through Rory’s epic journey, Penfold builds an awe-inspiring, light-filled environmental adventure story for readers, allowing us all to journey into this precious future Arctic wilderness.”

Sita Brahmachari, author of Where the River Runs Gold

“A powerful story of hope – a glimpse into a brighter future, a world where we have taken action to protect our fragile planet.”

Rashmi Sirdeshpande, author of Good News

“A beautifully crafted story of wild encounters and conservation; one that will keep pages turning and hearts beating from start to finish.”

Rachel Delahaye, author of Mort the Meek

“With just the right mix of spookiness, action, intrigue and mystery, Beyond the Frozen Horizon takes Nicola Penfold to the next level.”

Sinéad O’Hart, author of The Eye of the North

“A gripping story that drew me into its icy clutches with a dystopian climate mystery. Polar bear encounters, dog sled rides, blizzards and hugs with Arctic foxes, the action is both chilling and thrilling!”

Lou Abercrombie, author of Coming Up for Air

“Beautifully evocative with a fantastic cast of characters and, as always, an important yet lightly told message about the necessity of caring for our precious environment.”

Sharon Gosling, author of The Golden Butterfly

“A sublimely crafted tale of loss, friendship and bravery.”

Jo Clarke, author of Libby and the Parisian Puzzle

“A haunting tale of friendship, exploration and protecting our planet.”

Maria Kuzniar, author of The Ship of Shadows

“Nicola’s reverence for the natural world oozes from the pages of this breathtakingly beautiful story… This is storytelling at its very best.”

Kevin Cobane, teacher

“A high-stakes adventure that will leave readers thinking about their place and impact on the world for a very long time.”

Kate Heap, Scope for Imagination blog

“An eco-adventure, ghost story and love letter for a better world.”

Gill Pawley, Inkpots

“I loved this utterly compelling near future ecological thriller set in a vividly evoked remote Arctic landscape.”

Joy Court, UKLA

“A plot as devastating and mesmerising as the frozen landscape of the Arctic night.”

Lindsay Galvin, author of My Friend the Octopus

Background

In 2030, world leaders pledged a coordinated and unprecedented response to the Climate Crisis. Global Climate Laws were brought in, including a ban on the extraction and burning of fossil fuels, stringent targets to reduce the consumption of meat and dairy products and a ban on single-use plastic. World Wilderness Zones were also established, setting aside vast areas to absorb carbon and act as vital wildlife refuges. For the first time in history, wildlife was prioritized over humans and people were moved out of the Wilderness Zones. The High Arctic was one of these designated zones and included the archipelago of Svalbard.

Temperatures have continued to rise, but there is hope that the rate of warming has slowed.

Flight

I’d never been in the sky before.

It feels unnatural. A subversion of all the laws of physics, and all the Climate Laws too. Humans don’t belong in the air.

But I hadn’t reckoned on the excited twitch of my brain as the metal cylinder hurtled into the sky. Above the clouds, looking down on England as we left it behind for six whole weeks.

The box-like shapes of Mum’s and my estate, with its new build apartments and neat green spaces, and my sprawling academy school, glowing in the early morning light. Then more town buildings – the leisure centre, supermarket, hospital, sports stadium – and roads whirring with electric cars, until a swathe of green, like someone got a paint pot and threw it over the earth’s surface. One of the new forests, to suck up carbon and give wildlife a fighting chance to recover. The trees are a collage of shades and textures, in different brushstrokes – alder, cherry, maple, birch, willow, hawthorn. Somewhere in the tangle of trees is Dad’s wooden hut with a solar-panelled roof and a tiny annex that’s mine every second weekend.

I pull myself away from the window. A book’s open on the table in front of me. Creatures of the Far North. It was Dad’s gift to me for the trip, alongside a Polaroid camera that’s sunshine yellow and little boxes of film. “To capture your adventures,” Dad had said. He doesn’t trust phone cameras.

“How are you feeling, Rory?” Mum asks beside me. “Six weeks in the Arctic! It’s quite something, isn’t it? I hope we’re doing the right thing taking you out of school like this.”

I let the words drift over me. “It’s only Year Eight, Mum. It’s not like I have exams or anything.”

“You must still do the work you were set. I promised Ms Ali…”

Typical of Mum, to start up about school when I’m strapped in and there’s nowhere to run to. Does she expect me to have a textbook out instead? It’s not like I’m behind. It’s not the work that’s a problem for me at school.

I close my eyes deliberately.

Mum squeezes my hand. She whispers, “I’m sorry. We can sort it out later. Maybe you need a break first, time to reset your brain, switch off from all that.”

Neither of us wants to acknowledge what “that” is, but behind my eyes there’s a crowd of faces and taunts. That I’m strange and quiet. That I don’t belong. That I should run away with my dad to the woods. Mum swears I could fit in at school if I try, but I don’t seem to know how. It was different when I was younger and we lived in a line of terraced houses with parallel back gardens and my best friend in the whole world next door. Betty. Every morning we walked to school together, Dad waving us off with a smile.

Those houses are gone now. Our primary school as well. They were too old and draughty to bring up to new energy efficiency standards. Or, if you believe my dad, developers moved in waving green home grants and thick wads of cash. Either way, the wrecking ball came and the rubble was repurposed into apartment blocks.

Betty’s parents got jobs at one of the nuclear plants and moved out to the coast. We moved to one of the new estates. A two-bedroom cube of convenience on the tenth floor, with a tiny balcony and a couple of planters as outside space. Dad said it was bad for his soul, growing herbs in the sky, hearing neighbours through the walls. He said there wasn’t enough oxygen. He and Mum became angrier and angrier with each other until neither of them could stand it. Dad found a job as a ranger in one of the new forests that came with its own place to live.

Sometimes I take a bus back to where our old street was. It’s nice enough – there are reed banks and wildflower beds, bird feeders and children’s playgrounds. But I’ll never stop feeling sad about our old house. The back garden had a tangle of shrubs with a hidden space inside. Betty and I would lie there for hours listening to birdsong and the hum of the bees, being visited by neighbourhood cats.

“What are you thinking about?” Mum asks now, scrutinizing my face.

“Just school, I guess,” I say.

She squeezes my hand and stretches her legs out under the seat in front. Her face breaks into a sudden grin. “I can’t believe we’re doing this. You and me, girls together. We’re going to the far north, Rory. To the land of bears and ice and lights!”

“I thought you said it was going to be twenty-four-hour darkness!” I can’t resist saying. We’ll be arriving in the countdown to the polar night. Every day shorter than the last until the sun won’t rise at all till spring.

Mum laughs. “We have a few weeks of light first. Plus we’ll have the northern lights. The aurora borealis! We’re sure to see them, spending all that time on Svalbard.”

“Aurora borealis,” I repeat, enjoying the way the vowels feel in my mouth. Then “Spitsbergen,” I say, emphasizing the consonants in the name of the largest island in the Svalbard archipelago. It’s going to be our home for the next few weeks, in an old coal mining town that Mum’s new company, Greenlight, is reopening to extract rare earth metals. Silvery grey elements, magnetic and electrical, that make things faster, stronger, lighter, smaller. Batteries, wind turbines, electric cars, smart phones, cancer drugs – there’s a rare earth metal in all of them.

“Spitsbergen,” Mum says. “Hard to say without spitting!”

I laugh and she says it again, louder, with even more terrible enunciation. I look about to see if any of our fellow passengers hear, but they all have earplugs in, tuned in to something else.

I smile back at Mum. I wonder if I’d known her when she was my age, whether we’d have been friends.

I force school out of my head. All the girls I feel so separate from. I don’t want to bring it with me. That’s not what this trip is for.

“I can’t believe we’re flying!” I say. “I am so excited! We’re above the clouds!”

“I was a child the last time I took a plane,” Mum says dreamily. “We were going to Portugal. Me and your aunty Clem, and Granny and Grandpa. To a villa with a swimming pool on a clifftop. It was two years before the Climate Laws came in. It felt like heaven! I don’t suppose we’ll be swimming this time.” She pretends to shiver.

I frown. “I thought there was a pool? The most northerly swimming pool in the world, you said.” The most northerly pool in the most northerly town. The settlement also once boasted the most northerly school, before all the people left.

Mum nods. “Oh yes! I suppose we can use it. If there’s…” Her voice trails off.

“Time,” I finish for her. I can always see it in Mum’s face when work takes over. A wrinkling by the sides of her eyes; furrows deepening on her forehead.

“Well, you might not have time, but I will,” I vow petulantly, not caring how I sound. Not here on a plane that’s filled with grey middle-aged people, most of them barely bothered about the fact we’re flying. How can they not be gazing out of the window absorbing it all?

Aviation is meant to be for essential reasons only but some of the passengers look far too accustomed to it. They’re working on laptops, drinks on their tables clacking gently with ice. Some of them even have their eyes shut, sneaking in a quick snooze. What a waste!

Standards get eroded over time. That’s why Mum says the Svalbard Rare Earths Project is important. People only put up with so many restrictions, and for so long, and then they want life to advance again. Greenlight is one of the companies promising that can happen. They’re at the helm of the green economy.

Dad would say that’s dangerous propaganda and we should all be learning to live with less. And I’m in the middle. No one cares what I think, and I’m not sure what’s true anyway. What matters most is that I persuaded Mum to let me take a six-week break from school, and Mum persuaded Greenlight to let me go with her. It’s going to be the trip of a lifetime!

I hold my yellow camera up to the window and click. A few seconds later, a black square of recycled film is fed out into the air. I waft it gently between my finger and thumb as a little box of clouds appears. I’m going to stick it on the first page of my travel journal. I want to remember this feeling forever. We’re flying!

Airport

Tromsø airport is full of hot circulated air that makes me think of a hospital waiting room. A strange, stuffy space where no one stays very long – just passengers passing time before their next flight.

Except the staff in the coffee shop. I watch the woman serving. She’s young – she must only be a few years older than me, but she’s clearly out the other side of school. Independent, free, and glamorous in that way some people are without even trying.

As if she can sense me watching her, she catches my eye and beckons me over. I look around, in case her signal was actually meant for someone sitting behind me. Someone older and more worthy of attention. But there isn’t anyone, so I get up, propelled towards her.

Mum’s got her nose in some papers. “Don’t go out of sight, Rory. They’ll be calling our flight soon.” She purses her lips, puzzling over an anomaly in the geological survey she’s reviewing. She’s stressed about assumptions in the original site report for the island. Some other geologist wrote it, but it’s going to be Mum’s job to present an updated version to the Arctic Council when they make their final environmental assessment for the mine. I leave her lost in details about depths and seams and lengths of pipeline.

“You’re young, for a flight,” the coffee shop attendant says when I reach the counter.

“Yes, yes,” I say, stumbling over my feet slightly. The woman’s even prettier close up. She smells of petals, and I get this flashback to our old garden. Making perfume in the summer from fallen rose petals. Betty and I dabbing it on our necks. It smelled like ice cream. “I came from the UK. We’re waiting for a flight to Longyearbyen.”

“Longyearbyen? In Svalbard?” The woman’s voice rises in surprise.

“Yes. Then we’re getting a boat north to Pyramiden, the mining town,” I say, faster now, squeezing my fists together in excitement. “We’re with Greenlight. Well, my mum is. She’s working on the Svalbard project.”

The woman raises her eyebrows but keeps on smiling. “This time of year? I hope you’ve got enough layers to put on!”

“I have. Got warm things, I mean. We ordered them especially.” My suitcase is full of thick waterproof trousers, a weatherproof jacket like a quilt and the puffiest boots I ever saw. Snow boots. For real snow!

“Would you like a drink?” the woman offers. “On me. Or on my boss, rather!” She winks mischievously and checks over her shoulder, but the little kitchen area behind her is empty. I look down at the metallic counter with a meagre selection of sandwiches in paper bags and bottles of fruit juice with flavours I can’t decipher. “Take your pick. I don’t normally get to serve anyone under forty,” she says. “You’re refreshing for me.”

I like her choice of words, and the way she pronounces them in her Norwegian accent. I read her name badge. Nora.

“I’d like a tea, please,” I say, trying to sound grown up.

Nora laughs, like I deliberately cracked a joke. “So English! Tea, please!” Then her smile becomes fiercer as she starts making the drink. “Lucky English girl, taking her first flight.”

“Have you been up there?” I turn my head to the vaulted glass ceiling through which I can see grey sky.

“Of course not!” Nora laughs, brushing her hair back. “I’m a waitress in a coffee shop. I would never be permitted. You must be more important than me.”

She doesn’t look resentful or angry, but the words linger in the recycled airport air.

“It’s my mum that’s important,” I say. “At least her job is. She’s going to check the site and advise on all kinds of things.” I wave my hand vaguely. I don’t ever really know much of what Mum’s job involves, just that she’s contracted as new buildings are planned, to make site maps and advise the engineers on ground conditions. This will be the first time she’s worked for a mining company, but apparently she did a whole thesis on permafrost at university so she’s a great fit for the Arctic.

“Ah, your mother is a scientist,” Nora declares, pushing a cup across the counter to me.

“An environmental geologist,” I correct.

“Ah!” Nora says again, no less certainly. “She found the metals. These precious metals that will allow us to take flights and live in luxury again.”

There’s a strange tone to her voice. Not like the girls at school, when they throw jokes back and forth and ignore any attempts I make to join in. This is more a general disbelief that the world will ever be any different than it is now.

I shake my head, anxious to avoid misunderstandings. “Mum’s not been to Svalbard before. She’s just supervising the last stage of the environmental assessment. She’s taken me out of school, so I can be with her.”

I can’t resist getting that in. Nora must see the significance of this. It can’t have been long ago that she’d have been at school too, in a stiff-shouldered blazer. Like a hamster in a wheel, ever turning, only I’m getting to spring off for a while.

“Nora!” A cross voice sounds behind her, followed by words I don’t understand but I can tell the meaning of at once. Nora shouldn’t be talking to me. I’m not important enough and there are tables to be cleared. A man appears, his face red and bad-tempered.

Nora turns to the sink to wring out a cloth. “Good luck, English girl,” she says over her shoulder. “Watch out for the bears!”

Dirty water drips from the grey cloth into the silver bowl.

“Thank you for the tea!” I answer quietly, retreating away from the man’s glare.

I wander over to the window with my steaming mug of tea. The window’s large and round, like a spoked wheel.

I’d hoped for snow this far north, but rain is falling on the tarmac outside.

Rain is English like tea, I think, except in summer when we go for weeks and weeks without any rain at all. When the hosepipe ban starts and the parks and road verges turn to straw, and the fire stations are put on alert for wildfires.

Mum comes to stand beside me to look out at the runway, with its white and red planes and its spaceship control tower.

“You got a drink?” she asks, surprised.

“You want some?” I say, offering it to her.

Mum shakes her head. “No, you enjoy it. I’d just be trailing to the loo! It’s only ten minutes till boarding time – next stop Longyearbyen!”

There are hills in the distance, grey and rocky, with patches of orange moss and lichen. This is tundra – a landscape above the tree line. The only verticals visible on the slope are steadily turning wind turbines.

“Do you think it will be snowing when we get there?” I wonder out loud. The rain gleams on the tarmac like spilt oil.

“Some of the time,” Mum replies. “Apparently it can get windy too. Sometimes the wind blows the snow away into the sea.”

“I hope it’s snowing,” I say emphatically. “I want to walk through it and make footprints. Or snow angels!”

Mum smiles indulgently. “It did snow once. When you were a toddler. We took you to the park and you kept picking it up, until your fingers got too cold in your gloves and your toes in your wellington boots. We hadn’t thought to put extra socks on. You howled! Your dad had to carry you home on his back!”

She’s laughing.

I give an irritated grunt. “I didn’t know then, did I? That that was the last time I would see snow for a decade.” I can’t keep the irritation from my voice. Mum’s told this story before and for some reason it always annoys me. My one experience of snow and I was too young to make the most of it or remember.

I stare out of the window imagining landing on Svalbard. The land of snow and ice, bears, reindeer and white foxes. It seems almost impossible that it still exists.

Landing

I first spot the mountains topped in snow. Actual snow! Like icing sugar poured down from the stars. Or white cotton sheets, bleached in the sunlight.

A tingle runs through my shoulder blades.

“Look!” I whisper to Mum. “Look!” I can’t keep the tremble from my voice.

Triangular rockfaces rise up from the navy water of the fjords that surround the island. We swoop downwards, our plane a giant bird. I hold my breath as we sink further, into a landscape of orange and yellow, spread flat under high mountains.

The grey face of one of the mountains appears ominously close through the plane’s windows. Then a town, off to the left, and beneath us. It must be Longyearbyen. Our stopping point on Spitsbergen before we go by boat through the fjords up to Pyramiden tomorrow. There are rows of colourful wooden houses in red, orange, yellow, mint green and blue. They have steep pitched roofs so the snow falls off them more readily. There are less photogenic buildings too from past mining days – old lifting gear, a metal warehouse, cableways and cranes.

Some of the town is covered in snow but before I can look properly we’re past it, flying over the runway, fast, faster. I feel a flood of terror, that we’re going to sink into the dark water of the fjord ahead, but there’s a jolt as we bump down on to the runway, and a low screech as the plane’s brakes start to work.

Mum’s hand settles over mine as the plane slows. I realize how tightly I’m gripping the arm rest. My knuckles are hard as stone.

“Deep breaths, Rory!” Mum says, laughing gently. “We’re on solid ground again.”

“Has there been an avalanche?” I ask, pointing through the window to an assortment of buildings, half buried in snow, at the bottom of the mountain.

“The parts of the town still occupied have snow fencing to protect them,” Mum says, not quite answering my question. “Those buildings over there won’t be used any more. There are barely any people left here in the archipelago. Just a few climate scientists and university students, and of course people connected with Greenlight now, en route to the mine.”

“And the mining town we’re going to, Pyramiden, does that have snow fencing too?” I ask nervously. I’ve never thought about the power of snow before, to cover landscapes and buildings. Dad isn’t here to carry me back now.

“Of course!” Mum says, squeezing my hand. “I wouldn’t bring you here if it was unsafe. It’s going to be basic, but not unsafe. Providing you stay in the defined parts of the town. Which you need to anyway because of the bears.”

I nod, hugging my legs, allowing that tug of excitement to find its way back again. We’ve come to the far north. Whales, polar bears, reindeer, Arctic foxes, ptarmigans, ringed seals, walrus. I made a list on the plane of all the animals and birds that might still be here at this time of year. I’m going to take photos of everything. Not to mention the best light show on Earth – the aurora borealis.

It’s going to be a true adventure, like in the books Dad read to me when I was small. Tales of forests and frozen lakes and more stars than you ever would have believed existed, burning in galaxies light years away. Here we’re even further north than most of those stories.

I put my hand on the rounded square of window. I can feel the cold through the glass.

“Come on, Rory!” The seatbelt sign has flashed off and Mum’s opening the overhead locker to get down our hand luggage.

“We’ll find the hotel and get checked in, and then we can go sightseeing! Greenlight have said they’ll organize a guide for us.”

I stand up, the thrill of excitement burning in my chest now.

Stepping from the plane on to the runway, the air hits my face in a rush, crisp and cold, and I breathe it into my lungs, to experience it all through my body.

“Are you ready, Rory? Our adventure begins!” Mum says beside me, bundled up in her new thick coat, her breath spiralling out into the clear air.

Bear

Longyearbyen airport is smaller than Tromsø. It’s barely as big as the bus station back home.

The man at passport control frowns when Mum says we are with Greenlight, and hands us both forms to complete.

I pause at the section ‘Reason for essential travel’ and tug Mum’s arm to get her attention. She leans over and writes in capitals on the printed line: ‘CHILD OF GREENLIGHT EMPLOYEE (LONE PARENT)’. I pull a face.

Mum had to apply for an exemption to allow me to accompany her. She pretty much declared Dad parentally unfit in the process.

Dad didn’t object. He knew how badly I wanted not to go to school for a while. He’d seen me at my worst. The days I’d not made it into school and had bunked off to the forest instead, catching two buses there on my own. Mum had been furious, with Dad more than me. She said he encouraged it, which wasn’t fair.

I wish Dad could have come here with us. He’s never taken a flight his whole life. His parents wouldn’t have entertained the idea. They’d been living low impact lives years before the new laws made it compulsory.

The man peers at my form suspiciously, but it must pass whatever test it needs to because we’re nodded through without a smile. I gasp as we turn a sharp corner into baggage reclaim. Above the turning conveyor of assorted luggage is the giant white form of a polar bear.

“It’s stuffed!” I exclaim, caught between wonder and horror at the sight of the massive beast.

“Let’s hope so,” Mum says, walking up to it. “I suppose we have come to the home of the bears.”

“Living ones!” I squeal. “I didn’t think hunting was allowed.”

“Relax, Rory.” Mum laughs gently. “I’m sure this bear is much older than either of us. It’s looking a bit mangy, like those foxes out by your dad’s. Anyway, aren’t you pleased? Polar bears were top of your list of animals to see, weren’t they?”

“Mum!” I groan. “Taxidermy doesn’t count.”

“There are our suitcases, Rory! Quick!” Mum cries, running towards the conveyor. I help her heave our cases off the circular conveyor belt and on to a luggage trolley, which we wheel outside to find a taxi, the wheels skidding along the floor.

Out on the street, the snow has been scraped away and is piled up in slushy heaps. I glance at the people waiting in the queue ahead of us, wondering what they’re doing here and what their essential reasons are. They look more like business people than climate scientists or naturalists and I feel a pang of disappointment.

Since the Global Climate Laws came in, there’s been a rise in the numbers of animals in Svalbard. It’s gradual, but it’s happening. Like grizzly bears and Siberian tigers in the forests of Russia and Canada, and black rhinos and lions in Botswana’s Okavango Delta. That’s the point of the Wilderness Zones. And because these zones soak up carbon, they might save us too. If we leave them alone.

People are a slippery slope. If you say yes to one person, how can you say no to the next? And it doesn’t take many people before a wilderness isn’t really wild any more.

Mum and I stay glued to the car windows on the short drive into town. On one side is the sea, or the fjord rather – a deep narrow stretch of water reaching inland from the Greenland Sea. On the other side is a mountain. Both look as grey and stark as the other, and I’m glad when the cheery colours of the houses come into view, even if most of them look deserted.

We pull up on a long street with a few shops and more boarded-up buildings. There’s a neon hotel sign lit, however, making it clear where we’re headed.

“Enjoy your trip,” the taxi driver tells us neutrally. Mum opens her purse but the driver waves her hand dismissively. “It’s on the Greenlight account.”

In the hotel, Mum strides forwards to the reception desk to check us in. I can tell how excited she is about our time here, even if she has been muttering under her breath as she works through mistakes in the paperwork she’s been given.

There’s a bookcase in the reception area. ‘Ice Library’, a sign says over the top. I wander over. The books all have titles connected with the polar regions and I run my fingers over the spines greedily. I’m impatient to get into it for real now.

The young man on reception is asking about me and I kneel down beside the books, not wanting to listen.

I pick a book from the shelf. The cover shows a white lake surrounded by grey mountains, or perhaps it’s a fjord like the ones we just flew over. I read the title under my breath. “Dark Matter. A Ghost Story.” There’s a brown circle on the front where someone put down a mug of coffee.

Mum’s hands on my shoulders make me jump. She’s biting her lip.

“Was it OK?” I ask, a sudden sinking feeling in my stomach. “They’re not going to send me back home?”

Mum looks surprised. “Send you back? Of course not. It’s nothing about you.” She runs her fingers through her hair. “There’s a briefing I’m meant to attend in the hotel’s conference room.”

“Now?” I ask, pouting with annoyance. What about our plans to explore?

Mum sighs. “In fifteen minutes. It’s with the Greenlight company director, Andrei. He’s here in Longyearbyen meeting with investors. He wanted to catch me before we get the boat tomorrow. There was some background information I wasn’t informed of…”

I raise my eyebrows questioningly.

“Settlers. Old mining families,” Mum continues. “In Pyramiden.”

“But it’s a ghost town!” I retort.

Mum sinks down into one of the armchairs and makes a clucking sound at the front of her mouth. She’s thinking. “Apparently some of the workers stayed after the last attempt to make the old mine operational. Properly stayed, as in had families here. Children.” Her brow furrows extra deep as she says this last word.

“How do they survive there?” I ask, astonished at this new information. “What do they eat?”

“Reindeer. They’ve claimed subsistence hunting rights, just taking what they need to survive. And then they use whatever dried or canned food they manage to get their hands on, I imagine. It’s totally against Wilderness Zone rules.” Mum shakes her head. “No one even seems sure how many people there are, which is frustrating. The Arctic Council is meant to be on top of all this.”

“Does it make any difference for Greenlight, though?” I ask. “Having people around?”

“This is a wilderness project, Rory. They picked the site precisely because there isn’t anyone nearby.” I try not to rise at the sarcasm in Mum’s voice. She’s always stressed at the beginning of a new contract, and this is the biggest job she’s had in ages. Maybe ever.

I tilt my head. “They’re going to need people to work in the mine. Couldn’t they employ some of these settler people? Then they wouldn’t need to bring over as many workers. Surely that would be better – fewer flights.”

I expect Mum to agree with my suggestion but when she takes in what I’ve said she just purses her lips tighter. “Any miners from that time are probably too old to work now, and our methods are so different anyway. And any younger ones, well, what will they know about anything if they’ve lived their whole lives out here, closed off from the world?”

I stare back at her. It’s not like Mum to dismiss people she hasn’t met.

“Anyway, we’ll make it work,” she says with forced brightness. Her eyes go to the book in my hands. “A ghost story? I don’t want you having nightmares!”

“It might be fun,” I say defensively, but I put the book back on the shelf anyway. Nightmares are a sore point. I had so many after we left our old house and they only got worse after Dad moved out.

“Shall we go and see our room?” I say, trying to rescue the situation.

I’m excited about staying in a hotel, even if it is just for one night. It’s been years since I went on a holiday. And since Betty moved away, I haven’t even had a sleepover.

Mum looks back to a clock hanging over the reception desk. It’s huge, with smaller clocks around it showing the time in New York, Tokyo, Moscow and Bangkok. Behind the desk, the man smiles over at us and points to our suitcases, abandoned in the middle of the lobby like little islands. “Your room’s on the third floor. I can help with the cases if you like? They look heavy.”

“Oh yes, please,” Mum answers, standing up again. “That’s kind of you. And is it OK for my daughter to wait here this afternoon? It sounds like I need to hurry to the meeting room for that briefing.”

The man glances at me sympathetically. “Surely your daughter – Rory, isn’t it? – would like to explore our town while the light lasts? There’s less than an hour to go before sunset and you’re only here one night.”

“Yes, but…” Mum frowns. “That would be unsafe, wouldn’t it, on her own? The bears?”

My heart drums in my chest. Yesterday I was in my humdrum town and now there’s the prospect of running into a polar bear.

The man smiles. “You’ll be fine in the town itself, Rory. We have trip wire warning systems and the boundary is well marked. Just don’t go beyond there.”

I nod excitedly back at him. He must see the hunger in me to explore.

“I’ll be careful, Mum,” I promise. “I really want to see the seed vault. To take a photo, for Dad.”

The seed vault is dug into the mountainside above town, in case of further climate disaster or nuclear war or some other apocalyptic end. A million types of seeds, which could help people grow food crops if they needed to start from scratch. Dad and I found out about it on the computer in the town library. I clutch the camera strap around my neck, feeling sad for a moment, thinking of Dad out in the forest, watching the leaves change colour without me.

The man shakes his head. “I’m afraid the seed vault is too far out of town.”

I look at Mum, hoping she’ll have a suggestion. She’d been so sure about the guide Greenlight would provide for us in our short time here, but she only smiles vacantly. “Just walk up the main street then, Rory. Get a feel for the place. Buy some sweets or something, and take some pictures to show me over dinner. I promise you I’ll make up for it then.”

The man flicks me another sympathetic smile. I guess I’m exploring Longyearbyen alone.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)