2,76 €

Mehr erfahren.

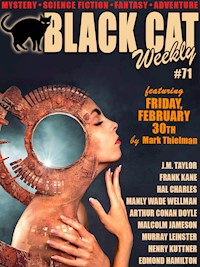

- Herausgeber: Black Cat Weekly

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

This issue, we have original mysteries by Mark Thielman (thanks to Acquiring Editor Michael Bracken) and Joslyn Chase, plus a modern classic by Eve Fisher (thanks to Acquiring Editor Barb Goffman). Our novel is a Golden Age tale by Isabel Ostrander. Of course, there’s also a solve-it-yourself puzzler from Hal Charles.

On the more fantastic side of things, we have a dark fantasy from British master Edmund Glasby, plus a classic tale by Allen Kim Lang...who, at age 95, is still with us. (His most recent story appeared in Analog in 2020.) Plus we have a Lancelot Biggs story by Nelson Bond, a classic SF story by Randall Garrett, and a fantasy novel by Manly Wade Wellman. Good stuff!

Here’s the complete lineup—

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“Dramatis Personae,” by Mark Thielman [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“The Black Bandana Kid Rides Again,” by Hal Blythe Charles [Solve-It-Yourself Mystery]

“Sophistication,” by Eve Fisher [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“A Killer View,” by Joslyn Chase [short story]

Ashes to Ashes, by Isabel Ostrander [novel]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“Something About Spiders,” by Edmund Glasby [short story]

“Lancelot Biggs Cooks a Pirate,” by Nelson S. Bond [short story]

“The Price of Eggs,” by Randall Garrett [short story]

“I, Gardener,” by Allen Kim Lang [short story]

Fearful Rock, by Manly Wade Wellman [novel]

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 834

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

TEAM BLACK CAT

THE CAT’S MEOW

DRAMATIS PERSONAE, by Mark Thielman

THE BLACK BANDANA KID RIDES AGAIN, by Hal Charles

SOPHISTICATION, by Eve Fisher

A KILLER VIEW, by Joslyn Chase

ASHES TO ASHES, by Isabel Ostrander

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

SOMETHING ABOUT SPIDERS by Edmund Glasby

LANCELOT BIGGS COOKS A PIRATE by Nelson S. Bond

THE PRICE OF EGGS, by Randall Garrett

I, GARDENER, by Allen Kim Lang

FEARFUL ROCK, by Manly Wade Wellman

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2024 by Wildside Press LLC.

Published by Black Cat Weekly

blackcatweekly.com

*

“Dramatis Personae” is copyright © 2024 by Mark Thielman and appears here for the first time.

“The Black Bandana Kid Rides Again” is copyright © 2022 by Hal Blythe and Charlie Sweet. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

“Sophistication” is copyright © 2007 by Eve Fisher. Originally published in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, May 2007. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“A Killer View” is copyright © 2024 by Joslyn Chase and appears here for the first time.

Ashes to Ashes, by Isabel Ostrander, was originally published in 1919.

“Something About Spiders” is copyright © 1961, 2012 by Edmund Glasby. Originally published in Supernatural Stories No. 45 (1961). Reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent, Cosmos Literary Agengy (U.K.)

“Lancelot Biggs Cooks a Pirate” by Nelson S. Bond, was originally published in FantasticAdventures, February 1940.

“The Price of Eggs,” by Randall Garrett, was originally published in Fantastic Science Fiction Stories, December 1959.

“I, Gardener,” by Allen Kim Lang, was originally published in Fantastic Science Fiction Stories, December 1959.

Fearful Rock, by Manly Wade Wellman, was originally published as a three-part serial in Weird Tales, February to April, 1939.

TEAM BLACK CAT

EDITOR

John Betancourt

ART DIRECTOR

Ron Miller

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Barb Goffman

Michael Bracken

Paul Di Filippo

Darrell Schweitzer

Cynthia M. Ward

PRODUCTION

Sam Hogan

Enid North

Karl Wurf

THE CAT’S MEOW

Welcome to Black Cat Weekly.

This issue, we have original mysteries by Mark Thielman (thanks to Acquiring Editor Michael Bracken) and Joslyn Chase, plus a modern classic by Eve Fisher (thanks to Acquiring Editor Barb Goffman). Our novel is a Golden Age tale by Isabel Ostrander. Of course, there’s also a solve-it-yourself puzzler from Hal Charles.

On the more fantastic side of things, we have a dark fantasy from British master Edmund Glasby, plus a classic tale by Allen Kim Lang...who, at age 95, is still with us. (His most recent story appeared in Analog in 2020.) Plus we have a Lancelot Biggs story by Nelson Bond, a classic SF story by Randall Garrett, and a fantasy novel by Manly Wade Wellman. Good stuff!

Here’s the complete lineup—

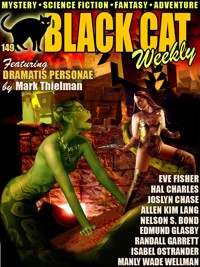

Cover Art: Ron Miller

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“Dramatis Personae,” by Mark Thielman [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“The Black Bandana Kid Rides Again,” by Hal Blythe Charles [Solve-It-Yourself Mystery]

“Sophistication,” by Eve Fisher [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“A Killer View,” by Joslyn Chase [short story]

Ashes to Ashes, by Isabel Ostrander [novel]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“Something About Spiders,” by Edmund Glasby [short story]

“Lancelot Biggs Cooks a Pirate,” by Nelson S. Bond [short story]

“The Price of Eggs,” by Randall Garrett [short story]

“I, Gardener,” by Allen Kim Lang [short story]

Fearful Rock, by Manly Wade Wellman [novel]

Until next time, happy reading!

—John Betancourt

Editor, Black Cat Weekly

DRAMATIS PERSONAE,by Mark Thielman

Blasius’s dying words, I hoped, had been witty.

A soldier directed me to a long, narrow room behind the theater’s stage. Blasius Pachomius’s body lay on the floor, clad in a blood-soaked tunic. I heard the scrape of sandal-clad feet as Narcissus Sura and Graccus Triarius joined me. No one averted their eyes. We had each commanded troops in the First Jewish-Roman War and regularly attended the gladiatorial games. Neither a lifeless body nor a little blood would shock us.

“A most inconvenient time.” Narcissus always delivered his words in a gravelly whisper, a result of a throat wound he had received during the siege of Jerusalem.

I nodded. “Certainly for old Blasius here.”

Narcissus’s eyes flared. “Cicero Caudinus, you know how restless the people are becoming. Two gamblers fighting over a lost wager is one thing. But an unresolved stabbing only adds to our difficulties.”

Narcissus served as one of the Duumviri, the magistrates who oversaw the city’s administration. This death would prove another burden to him. Anyone who walked the market could feel this city becoming a boiling pot.

“Cicero Caudinus meant no offense,” Graccus said. “It was he, after all, who sponsored this play.” Graccus was one of the Aedile, one of two deputies to the Duumviri.

Narcissus grunted. “Then I doubt you got value for the gold you handed this playwright.”

Graccus’s eyes returned to the body. “Certainly not the work of a soldier.”

Multiple cuts and tears rent Blasius’s garment. Some wounds appeared minor, merely damaging the cloth and scratching the skin. Others had penetrated. A great deal of blood had been shed. I agreed with Graccus’s assessment. None of the injuries showed the purity of thrust a trained Roman legionnaire would deliver. I widened my gaze. Near us, a pottery jug smelled of fine wine. At the far end of the room, away from the body, I saw the tangled mass of Blasius’s bedcovers.

Narcissus held his fingers a blade’s width apart. “Although the wounds appear to have been caused by a gladius.” He referred to the sword carried by the legions.

My thoughts drifted.

“Are you listening, Cicero?”

The question brought me back. I looked to Narcissus, who apparently had been speaking.

“I apologize, Duumvir.”

The older man’s frown deepened. “I said that this will not do. Have you seen the triremes and merchant ships in the harbor? We grow fat and rich. These should be grand times. But first, these minor earthquakes occur. Then, reliable wells run dry. The citizens are unsettled. There is talk of people seeing spirits. Those in the market claim to have witnessed silvery wisps rising from the earth. And now a murderer runs loose. This will not do.” He snapped his fingers. A soldier appeared at Narcissus’s side holding a goblet. The Duumvir drained the cup and then tossed it aside. It landed with a clank and rolled. “This will not do,” he repeated.

I nodded in agreement. “That is why I commissioned the writing of this play. I felt that something lighthearted, a comedy, might help the people forget these troubles.”

“And seeing the merit of this idea, I promptly licensed it,” Graccus said. “Yesterday, as you know, was the final performance. I do feel the play lifted the morale of the citizenry.”

“Yes, yes,” Narcissus said, although his mind appeared elsewhere.

I gestured toward the dead man. “I had a conversation with him before they performed yesterday.”

From the corner of my eye, I saw Graccus recoil slightly. He obviously found the idea of speaking with a lowborn actor distasteful.

“I have been traveling, conducting imperial business. I recently returned and visited the theater yesterday. I had not yet had the opportunity to see the play I sponsored.”

Narcissus nodded. As a survivor of imperial politics, he kept track of the whereabouts of friends and potential rivals.

“Blasius had called a special rehearsal before the final performance. I arrived as they began and watched from my usual seat in the ima.” I had no need to point out for either Graccus or Narcissus the seats reserved for senators and those of noble birth. They both had places in the lowermost tier as well.

“Blasius Pachomius stopped the rehearsal and invited me onto the stage.”

Graccus’s face tightened.

I acknowledged his discomfort. “No doubt my face also displayed some displeasure at the request. With no acting training, I have little skill at masking my emotions. One’s standing might suffer greatly if he were to acquire the reputation as one who associates with actors.”

Narcissus bristled.

Graccus made a quick hand wave and spoke in a husky voice. “Of course, some associations are better than others.”

I ignored the innuendo. “As I had paid for the staging of this play, I felt obliged to make sure that the production would be entertaining.”

“And so, you went?” Graccus asked.

“Blasius Pachomius said that I would do the actors a great kindness.” I paused and shrugged. Both men nodded. As Romans, they understood duty. “I climbed the stairs leading up onto the stage. When I arrived, Blasius Pachomius pushed himself up from his chair. He raised his hand to the heavens as if he were giving the final speech of his production. He thanked me for my attendance at the final rehearsal as well as my gracious patronage. I could smell that he’d been drinking. I also saw a large goblet of dark wine. The surface rippled as the cup sat on the stage floor.”

“Did the man seem to sense his impending death?” Narcissus asked.

I considered the question. “Blasius had dark circles under his eyes. His jowls, always full, shook like jelly yesterday. The skin of his face looked ashen. I considered summoning a physician to protect my investment.”

“The gods had marked him for death,” Graccus said.

I raised a finger. “I might agree with your conclusion, but then Blasius lowered his hand and covered his heart. ‘Cicero Caudinus, this play may be my greatest creation. I know that I must look like the very image of death. Still, I assure you that it is only because of my efforts to give you a production worthy of your generosity. Even this day, I have added extra lines to improve my work.’”

Graccus pantomimed a set of scales with his hands. “We have the work of the gods or wine and fatigue.” As he spoke, he raised and lowered his palms.

I nodded. “Although, at the time, I attributed Blasius’s appearance to the grape.” I paused a moment before continuing. “Then he said something that disturbed me.”

Both men leaned in slightly.

“Blasius fixed his gaze on me. He whispered to me that when the actors had finished the performances here that he intended to take the play to Rome. He told me that I would become known in the capital as a patron of the dramatic arts.”

Narcissus and Graccus looked as if they had just tasted something foul.

“Again, I am sure that my face revealed me. I had no desire to associate myself with the commercial theater in Rome. My sponsorship had been intended only to entertain and to distract the local citizens.”

The two men nodded in agreement.

“Wishing to change the subject, I ordered Blasius to tell me about the play.”

“The current state of affairs has kept me too busy for such trifles,” Narcissus claimed. Graccus, I knew, had seen the production and chose to remain silent.

“The playwright’s voice took on that airy quality writers get when talking about their work. Then, Blasius told me that when I had commissioned him to write the play, he had settled himself in the cavea, the general audience’s seats. He imagined himself looking upon the actors as the people would. He said that he saw the mountains rising behind the stage. Suddenly, the play leaped into his head as if it rode on the back of a stag. Blasius said that he thought immediately of Thebes. He would have an adulescens, a young man, a noble, who falls hopelessly in love with a slave girl. His family, of course, would never allow him to marry so far beneath himself. The boy turns to Tiresias, the blind prophet of Apollo. In a grand scene, Tiresias majestically floats down from the wings. Being an augury, he makes his predictions based upon the flight of the birds.’

“But he is blind,” Narcissus said. “How did a blind man see the birds?”

“An excellent question. The very one I put to Blasius,” I said. “He pointed out that the play was a comedy and unbound by the rules of the earth. It must only make sense within the theater. Then he pointed out something I found valuable. He said that with talk throughout the city of spirits rising like vapors from the ground, he wanted to remind the audience that the great powers, the gods, come down from above. Tiresias’s prophecy brings the couple together. The play’s purpose was to pacify the citizens.”

Narcissus nodded. “Continue.”

“In the end, the adulescens won the virgo, the young maiden. The audience learned that she was freeborn and eligible to be married. Tiresias was always aware of her identity, for he foresaw the future and knew there would be a happy ending. He slid a golden bracelet off his arm and onto hers. She was revealed.”

“And is that all he had to say?” Narcissus asked.

“When he had finished his narration, Blasius paused, bent down, and collected his goblet. He raised it in a toast to himself. He saluted the play, the author, and his actors. Somewhat as an afterthought, he saluted the sponsor.”

“Rather full of himself,” Narcissus said.

“Blasius did give considerable credit to the actors. They are exquisite,” he told me. “An actual blind man played the character of Tiresias. Watching Linus Sacerdos, Blasius said, made you feel that you were in the presence of the soothsayer himself.”

Narcissus stroked his chin with his fingers. “I see why you thought this might be helpful, Cicero Caudinus. This play might well have comforted the people during these troubled times.”

As if to emphasize his words, I felt an earth tremor beneath my feet.

Narcissus looked at me. “Cicero, you had a fine plan, but unfortunately, events have conspired against you. To have the playwright murdered after the final performance has made the people more agitated. I must attend to other problems. I have ordered soldiers to search the theater. I would like you to remain here and discern who committed this murder.”

“But Duumvir—” I began.

Narcissus cut me off before I could make my protest. “As a Roman, I know that you understand duty. Graccus, assist him.”

“And if we discover the killer?” I asked.

“When…when you reveal the killer, bring him to me. I shall find him guilty, and he will be executed,” Narcissus said. “Another spectacle to distract the citizens.” Adjusting his toga, he turned on his sandals and left the small room.

Graccus and I watched until the last fold of his toga disappeared. “He already knew the details of your play,” he said quietly. “Alexis Gallus is his consort. Blasius cast her as the virgo.” Graccus could hardly contain his snicker as he spoke.

Before I could comment, we were interrupted by the shouts of soldiers. The centurion appeared in the doorway. He threw his arm out in a salute. “Aedile, my men have found something.”

“Take us there,” Graccus ordered.

The centurion crisply set off, marching in the direction Narcissus had traveled. Then, he turned sharply and led us down a hallway to the main arcade behind the stage. The centurion snapped his fingers. “Torch,” he ordered. A soldier raced to his side carrying a firebrand. The centurion held the flame close to a column supporting the roof. The flickering light illuminated a bloody handprint. “We found two more of them. One on each of the columns,” he said.

“Show me,” Graccus ordered.

The officer took him along the path. The centurion held the light next to each column so that Graccus might see.

I remained behind. Collecting a torch of my own, I closely examined the first print. I spread my fingers. The bloody stain proved to be smaller than my own hand. I had no question that it was a palm print, for the edges were crisp. The center had an empty band across the middle. A smaller band marked one of the fingers.

I felt the sconce nearest the print. Residual warmth emanated from the bronze. In the confusion since the murder, the torches had been left unattended. The fires in the hall had been allowed to burn out.

“Cicero Caudinus, come see this,” Graccus said.

I followed his path, pausing briefly to survey the other palm prints. Each appeared to have a common source.

Graccus stood beside the last column. “Look at the direction of the fingers. The killer traveled this way after the murder.” He gestured to a closed door. “What is in here?”

“One of the actors rents this room as his apartment, Aedile. We were just about to search it,” the centurion said.

Graccus Triarius nodded.

The centurion threw open the door. The two soldiers rushed inside. A small man on the other side sat up in bed. He raised his arms and immediately began throwing his head in all directions. “Who? What—”

“Silence!” the centurion said. “You are in the presence of the Aedile.”

Graccus and I entered the room and looked down upon Linus Sacerdos.

“My apologies; if I had known you were coming, I would have dressed.” As he spoke, Linus smoothed the worn wool blanket covering him. His head swiveled around the room. Even in the room’s weak light, I could see the milky white glaze covering his sightless eyes.

“And no doubt cleaned your apartment,” the centurion said. With a nod, he gestured towards a basket full of sticks and assorted handles. Graccus and I followed his gaze. The centurion pinched one between his thumb and forefinger and carefully lifted it up. He held a bloody gladius.

The blind man turned his head toward the centurion. “You have found my props. I use them in my performances.”

“And in your crimes,” Graccus said. “Centurion, take him to Narcissus Sura.” He turned to me. “Cicero, you lucky dog. You have solved this case and can still return to your villa before cena. You will have a full belly and the favor of the Duumviri.”

I held up my hand to pause his speech. Walking to the actor, I grasped his wrists and brought the man’s hands to my face. “They smell of wine. I see no blood.”

“Easily washed away,” Graccus said.

I looked at the officer. “Centurion. Might I ask that your soldiers chain this man and guard him? I should like to speak with him further.”

The centurion’s eyes shifted to the Aedile. After a moment, Graccus nodded. The centurion pointed at a soldier who seized the actor, pulling him from the bed. The foot soldier dragged Linus Sacerdos down the hall while the small man cried his innocence.

Reaching into my bag of coins, I withdrew a sestertius. “Centurion, there is a bakery down the street. Send a man to buy me two loaves of bread.”

He looked to the Aedile. Graccus glanced at me.

“As you noted, this may take me through the cena,” I said.

Graccus nodded. A soldier took the coin and turned to leave.

“Wait,” I said, handing over another sestertius. “Have the baker add a small bag of wheat.”

The soldier acknowledged the order with a sharp snap of his head. He left the room, followed by the centurion.

Graccus kneaded his forehead. “And why aren’t we accepting the obvious answer?”

“Because sometimes the answer is not obvious,” I said.

He forced a laugh. “You speak in riddles. You sound like Pliny the Elder.”

“I shall take that as a compliment. Pliny has taught me much of the natural world.”

Graccus’s mouth became a frown. “What do you want to do?”

“I should like to speak with the actors.”

His frown deepened. “The actors.”

I nodded. “Let us begin with the principals.” I led him outside onto the stage. By my reckoning, the sun lay just past the sixth hour. I could hear the nervous whinnying of horses outside the theater. The animals, I knew, were more attuned to the subtle shaking of the earth. No birds flew in the sky. An unsettled feeling hung in the air. That could prove helpful. An anxious atmosphere would make it more difficult for those we interviewed to remain calm. I directed a soldier to bring a table and two sellas, simple chairs upon which Graccus and I would sit. Those to whom we spoke would stand.

“Centurion, bring us one of the actors,” I said.

He turned and pointed to a soldier.

The guard returned directly. He steered a man, maintaining a firm grip on his shoulder. The legionnaire deposited him before us and took two steps backward. His heavy footfalls echoed on the wooden stage floor.

“My Lord,” the soldier said. “He was found hiding away from the theater.”

Although large, the man shook with fear, his voice quavered. “I wasn’t hiding. I live above the tavern.”

“What is your name?” I asked, doing nothing to put him at ease.

“I am Verus Cinna. I am a slave owned by the theater company. You saw me yesterday. I play the role of Jacinthus, the adulescens. I was a young nobleman in love with a slave girl. Tiresias, the prophet, helps me to marry.”

I looked at him. “From this distance, I see that you are much older than the role you play.”

He nodded in agreement. “With my mask, I have long brown hair. The crowd would recognize me as a youth. As a mature man, I can project my voice to the top of the cavea. Blasius Pachomius always said that my voice carried so well that even the lowliest plebian could hear the words.”

The big man had a broad chest. I had no doubt that Verus’s voice reached the upper tier. “And why did Blasius change the play for the final performance?”

Verus shrugged. “I do not know. He added lines for Alexis Gallus about the gods.”

“Where were you last night?”

“We celebrated the end of the play. Linus Sacerdos quickly became drunk and went to bed. The boy can hold but a thimble full.”

“Or perhaps he feigns,” Graccus said.

Linus Sarcerdos cocked his head, considering the idea.

“And what of you?” I asked.

“I went home.”

“Alone?”

“When you live above a tavern, it is easy to find wine and friends,” he said.

“And Alexis, what of her?”

He shrugged. “I do not know.”

My eyes bored into him. “And you know Blasius is dead.”

His knees began to shake. His mouth opened, but no words came out.

I supplied them for him. “I think that you might have killed him.”

Verus pitched forward until his knees hit the stage floor with a heavy thud. He drew himself back and sat upon his haunches. His wide eyes showed desperation. His right hand clutched at his throat. After a moment, he spoke, his voice barely above a whisper. “I swear it, sir. I know nothing of this. I am owned by the theater company. If Blasius took his play to Rome, I would remain behind. That would bring me sadness, for I truly enjoy the role he wrote for me. But suppose the theater closes because of the scandal surrounding the murdered playwright. Then, I may be sold into labor for which I am ill-trained and unprepared.”

I looked at the soldier. “Put him up and bring us another.”

Verus seemed almost too weak to stand. The legionnaire nearly dragged him off the stage.

Graccus Triarius looked at me. “He tells a convincing story.”

I shrugged. “Verus is an actor. He could make any role believable.”

“He is owned by the company. I have seen the tax records.”

Before we could discuss the matter further, the soldier returned. I detected more deference when he escorted Alexis Gallus. The guard held the door and never laid a hand upon her. She wore a new toga of the finest material.

Alexis Gallus walked confidently to the front of the table. She looked first at Graccus before shifting her gaze to me. “I am Alexis Gallus. I play the young maiden.”

I did not break my eye contact with her to see if Graccus again smiled at this comment. “And do you know why you are here?”

“Because Blasius is dead.”

“And why should we not suspect you?” I asked.

“Perhaps you should.”

This made Graccus lean forward in his chair.

After a pause, which I might only describe as dramatic, she raised her hand and spread her fingers wide apart. “I could easily give you five reasons why I am not the one you seek. But I would rather discuss it outside the hearing of others.” With her head, she motioned to the soldier.

My eyes looked first at her. Then, they moved to the legionnaire. Finally, they met Graccus’s. We both nodded.

“Guard,” he said, “leave us. I will call you back shortly.”

He turned and marched off the stage.

She waited until the soldier was out of sight. She held her thumb up in the air. “I am the consort of Narcissus Sura. I lead a comfortable life I would not readily jeopardize.” She extended her index finger. “I am a liberta. I was born into slavery and earned my freedom through my work on the stage.” She extended her other fingers. “I have been gifted with a great role. A role that Blasius and I could take to Rome. Last night, he gave me more lines. Have you heard of Claudia Acte? An actress in Rome whom the Emperor Nero took as a mistress. She became wealthy and powerful. I would not wish to jeopardize any of that.”

“And where did you go after the party?” I asked.

The corners of her mouth dipped slightly. “Narcissus expected me. I spent some time alone to prepare myself.”

Her eyes dared me to challenge her statement. I looked to Graccus to see if he had questions. He shook his head.

Alexis Gallus looked at us. Her eyes, this time, showed concern. “I have put my welfare in your discretion. I am trusting that you feel no need to discuss my possible departure with Narcissus Sura.”

Before I could speak, Graccus looked at her. “Duumvir Sura tasked us with finding the guilty party. He did not say he wanted an explanation about why others were not guilty.”

She bowed her head. “Thank you, Aedile.”

I stood and walked around the table. Clasping her hands, I brought them to my face. They were clean and smelled of lemons from the Amalfi coast. I released my grip. “What Graccus Triarius says is true.”

Alexis smiled, then turned and briskly walked off stage.

The soldier brought Linus back before us. He walked with his head bowed and shoulders stooped, the shackles around his ankles shortening his steps. He looked even smaller approaching us than when we found him in his apartment.

Graccus did not allow the man to reach the table before he began his interrogation. “Tell us why you did this.”

“Mercy,” Linus cried. “I did nothing. I am innocent.”

“The innocent need justice, not mercy,” Graccus said. “Your words betray you.”

A piteous cry emerged from Linus’s throat.

“Tell me,” I said, “Are you also a slave?”

Linus paused and took great gulps of air as he brought himself under control. He turned his head towards me. “I am a freedman. My father was an actor. I was born into this life.”

“And how long have you been blind?”

“All my life, sir. My mother hoped I would grow into my sight.”

“Is it difficult to be a blind actor?” I asked. Beside me, I heard Graccus exhale.

Linus shook his head. “The ancients tell us that Homer was blind, sir. There is a long tradition of us. I have been trained to memorize quickly. With my size, I am easy to lower down. I routinely play the role of soothsayer.” He again shook his head. Linus seemed almost to have forgotten that he was shackled. “Far harder for me to learn any other job. My mother tried to make me help her with laundry and cleaning.”

Graccus leaned forward. His voice had lost its earlier menace. “And did you help your mother prepare meals?”

Linus nodded. “Until I left home.”

“And how does a blind man cut vegetables to make stew?” Graccus asked.

Linus pantomimed the action. “I align them with this hand and cut them where this finger tells me.”

“So, you are skilled with a knife,” Graccus said.

Linus jumped back, entangling himself in his chains and nearly falling. “No sir, I mean, I can cut vegetables.”

“But a man is different, isn’t he? That is why you were left to slash and cut. Blasius would not stay still for you to put a finger touching a mortal spot.”

Linus raised his hands and assumed a prayerful stance. “I beg you, sir. I did no such thing.”

“Why should we believe you, Linus?” I asked.

“Where would I go? How could I run? We celebrated the final performance yesterday. We opened a bottle of Falerian wine. I drank and fell into bed, exhausted from the performance and the drink. I only awoke when you entered my room.”

“Why did Blasius change the lines of the play?” Graccus asked. “When Alexis says, ‘tell the gods you’ve stolen from me. They are not blind to what has happened.’ Is that not an acknowledgment that you, Tiresias, were a thief? He inserted a message into the play to alert us to his killer.”

“She took the adolescens’ heart. Blasius wanted to invoke the gods more. He thought the line would help make the play popular in Rome. He was testing it here,” Linus’s words tumbled out rapidly.

Graccus sat back. His satisfied look told me that he needed no more information.

I looked to Linus and then to the soldier. “Take him.”

When the two of them had disappeared, Graccus looked at me. “I still maintain that the answer is obvious.”

“I agree.” I turned first on one soldier. After collecting the package of wheat he’d purchased, I whispered additional instructions. His head snapped understanding, and he disappeared. I turned to the other soldier. “Bring all three of them back.”

A flash of confusion crossed the soldier’s face. Then, he saluted and marched off, returning shortly with Verus, Alexis, and Linus.

I took my small package of wheat and poured the grains into each of their hands. “Put these into your mouth, but do not swallow them.”

Verus, Alexis, and Linus exchanged looks. Then, they each brought their hands to their mouths.

I spoke to the centurion who stood nearby. “Draw your sword.”

We all heard the metallic sound of the gladius sliding from its sheath.

My attention remained on the soldier. “I am going to ask these three a question. If you do not hear an answer from them, I order you to stab them without hesitation.”

“Yes, sir,” the centurion said. His narrowed eyes and grim-set mouth left no doubt about his readiness to carry out my command.

I came around from behind the table and stood before the three actors. I beckoned for Graccus Triarius to join me. Then, I turned my attention back to the three. “I want each of you to answer promptly. Did you kill Blasius Pachomius?”

“No,” they replied in unison.

“Spit out the wheat,” I commanded.

When they had, I turned my attention to Verus. “Show me your tongue.” I ordered the others to do the same. “Look at them, Graccus.”

He slowly made his way down the line, examining their mouths with the care of Rome’s finest physician.

“Pliny the Elder taught me that lying, particularly under stress, has certain physical effects. The heart beats faster. The hands tremble. The mouth becomes dry. The body has difficulty gathering saliva. Who could not spit out the wheat grains?”

He turned immediately and pointed at Alexis Gallus.

I nodded. “She is your liar.”

Anything Graccus had to say was drowned out by Alexis Gallus.

“You propose to find me guilty because I do not eat seed to your liking.”

I saw Graccus’s faint nod of agreement from the corner of my eye.

“I do not accuse you based on the wheat test. That merely confirms what I have learned,” I said.

“Nonsense,” Alexis said.

“No one except you held dreams of going to Rome. The others are provincial players and know their place. Blasius Pachomius played upon your dreams. He gave you more lines, an actor’s aphrodisiac. He used your desire to become the next Claudia Acte to seduce you. After the play’s last night, I suspect he told you the truth. Actors from the countryside would not be successful in Rome. He needed famous actors and actresses. Drink makes a man foolish or honest, occasionally both. You learned that you had been manipulated. In your rage, you lashed out violently. As someone who had spent a lifetime on the stage, you had no skill with a real sword. You slashed clumsily, making a bloody mess.”

Graccus put a hand upon my toga and whispered. “She is the consort of Narcissus.”

I ignored him. “You knew where Linus slept. He lived at the theater. Easy enough to hide the gladius in his room. Wine had the man too deeply asleep to hear your entry. Even if he had awakened, he could not see you.”

“He went there. The handprints showed you,” Alexis said.

“Yes, the handprints,” I said. “Although each of you is righthanded, we know they do not belong to Verus Cinna. He is too big, his hands too large.”

Verus nodded, his eyes straying down to study his palm.

“Alexis Gallus, you and Linus displayed your hands to us during your interviews.”

Verus’s eyes flicked back and forth between the other two actors.

“During the play, Linus slides a bracelet over his hand and onto yours. I daresay they are approximately the same size.”

Verus nodded.

“The handprints show a distinct pattern. An empty space in the middle of each.” I shifted my focus. “Centurion, how does one properly hold a sword?”

“Firm enough not to drop the weapon in battle but loose enough to give maximum flexibility.” He rotated his wrist, allowing the drawn blade to dance in his hand as a demonstration.

“Thank you, Centurion.” I turned to the actors. “The killer grasped the hilt so tightly that no blood seeped to the palm. That tells me a novice clasped the blade. It also tells me that the novice was enraged, wringing the life from the sword grip as she struck down the man who had spurned her.”

Verus, I saw, squeezed a fist, testing my statement.

“We found tangled blankets in the dressing room apart from Blasius’s body. To be abandoned after one last tryst could certainly produce wrath,” I said.

Alexis said nothing.

I spread out my fingers. “Look to the handprints. The edges are crisp. A blind man feels his way along. He gropes. The hand slides, for he has no other way to see. The edges are blurred. A sighted person in a lit passage picks her hand up as she walks. She has no need of touch. Look at the intact handprints. The image left behind has the sharp edges of the sighted.”

I paused and turned my attention back to Graccus Triarius. “Finally, there is evidence of a ring on the killer’s finger. Alexis’s hands smell of fresh lemon. They have been recently washed. I’ve sent the soldier to examine her jewelry. She may not have been so careful.”

The actress’s eyes briefly flared before she regained control.

I poured the few remaining wheat grains on the table. “These kernels merely confirmed what I had already observed. Alexis Gallus is your killer.”

Alexis Gallus stared at me, all attempts at self-control abandoned. I felt sure these fiery eyes were the last ones Blasius Pachomius saw. “Duumvir Sura will hear of this. I demand to see him.”

And Narcissus did hear of it. And saw the recovered ring with a trace of blood upon it. But with the earth tremors, the ground swells, and the reports of gaseous ghosts rising from the earth, he elected not to have his consort executed for the crime. I am sure that he had his reasons.

* * * *

“So nothing will happen to her?” Linus asked.

“Unlikely,” I said. “I will state my case to Pliny the Elder and ask to see the Emperor in Rome. He will, however, likely treat a provincial murder as a matter for the local administration. At least Narcissus Sura allowed you and Verus to travel with me. He did not order you both crucified to pacify the citizenry.” We spoke from the deck of a trireme, Verus and I watching as the boat sailed from the port.

“So nothing will happen to her,” Linus repeated.

I patted the young man on the back. “Her fate will be left to the gods.”

From the back of the boat, Pompeii faded in the distance. Behind the city, a thin finger of smoke arose from Vesuvius.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mark Thielman is a criminal magistrate working in Fort Worth, Texas. He is the author of more than thirty published short stories. His short fiction has appeared in Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, Black Cat Weekly, Mystery Magazine, and a number of anthologies.

THE BLACK BANDANA KID RIDES AGAIN,by Hal Charles

“You lost a comic book that might be worth twenty-thousand dollars?” State Police Detective Kelly Stone said to her younger brother. “How is that possible?”

“Not just any comic, but The Black Bandana Kid #1,” replied the sheepish twelve-year-old. “During her spring cleaning, Mom found a box of old comics in the attic, gave them to me, and told me to throw them out.”

“And what did you do with them, Chad?”

“When I saw BBK1 in the box, I bagged it, backed it, and sent it off to be graded. It came back a 9.5. Almost a perfect 10.”

“Why are twenty pages of cheap paper so valuable?”

“BBK1 was published back in the early 1950s when all the lead cowboys were male. The Black Bandana Kid’s secret identity, however, is that of a woman. The Internet claims she’s some sort of ‘early feminist pop culture icon,’ whatever that means.”

“Back to my original question…”

“I took it this morning with some comics I wanted to sell to the local ComicCon. Made almost a thousand on them. I only went to three booths, so I must have lost BBK1 at one of them.”

“Why take a valuable comic with you if you didn’t intend to sell it?”

Chad looked up at Kelly. “I guess I just wanted to show it off.”

“Get your coat, kid,” said Kelly. “You’re being taken for a ride downtown.”

Dressed only in a gray sports coat and black pants, Kelly felt out of place among the various costumed superheroes she recognized from her youth and the movies.

“You could have warned me about the convention’s dress code, Chad.”

“Just tell everybody The Black Bandana Kid is your alter ego,” he said with a grin at his sister’s uneasiness. “There’s one of the booths I visited, sis.”

Kelly held open her coat so the booth’s proprietor could see her badge and said, “Chad here tells me he lost something.”

Standing in front of a BEST PRICES sign, the proprietor scrutinized the twelve-year-old, then said, “I think I may have bought a few comics from him this morning.”

“You got a copy a The Black Bandana Kid #1 around here?” pressed the detective.

“Look at these comics,” the proprietor said, pointing. “They’re all funny animals and loveable teens. You see any westerns in my boxes? Feel free to look through my selections, though, officer.”

After a thorough search of the booth turned up nothing, Kelly said to Chad, “Next.”

Her brother led her to a bigger booth, where a man in a mustache stood in front of a LARGEST SELECTION sign. Subtly badging him, Kelly said, “Chad thinks he lost something here.”

“Look, if the kid wants to return the money I gave him, he can have his comics back.”

“We were looking for The Black Bandana Kid #1.”

“Not a chance I got it. I don’t do Golden Age comics. That’s from 1938 to 1956.”

Kelly and her brother finally located the third booth, which was highlighted by a DO NOT TOUCH THE BOOKS sign. Suddenly Chad started pointing at a comic that was sitting on a rack in the back of the booth. “That’s it.”

“You want to buy it?” said the proprietor, overhearing him. “Afraid it’s awfully expensive.”

“But I own it already,” protested Chad.

“Can you prove it?” said the gloved seller, turning belligerent.

Pulling back her coat so that he could see her badge, Kelly said, “Did you buy a few books from Chad this morning?”

“The kid’s face looks familiar,” admitted the man.

“I remember handing him five books, and he kept handing them back,” said Chad. “He did it so many times I got confused.”

“If you’re accusing me of stealing that comic,” the merchant said, indicating BBK1, “you’ll have to prove it. Can you do that?”

When Kelly explained how she could, the merchant quickly confessed to stealing Chad’s valuable comic book.

SOLUTION

Kelly pointed out that since the merchant was wearing gloves, Chad’s prints would be the only ones on the cellophane wrapper around the valuable comic displayed well behind the do-not-touch sign. The merchant immediately confessed and spent the next few years in a place where he had plenty of time to read all the comics he wanted.

The Barb Goffman Presents series showcasesthe best in modern mystery and crime stories,

personally selected by one of the most acclaimed

short stories authors and editors in the mystery

field, Barb Goffman, forBlack Cat Weekly.

SOPHISTICATION,by Eve Fisher

You might be surprised, but the real-estate business does well in Laskin, South Dakota. Farmers retire and move to town, some people get a raise and buy bigger, some don’t and buy smaller, and a lot of the kids who couldn’t wait to get out of this small town move back as soon as they have children of their own. There’s a lot of turnover.

There are also a few white elephants. The Burrell place, for example—a white wedding cake of a house, complete with five Corinthian columns and a lot of gingerbread. It was too big for any family but the Burrells, who’d had fourteen children, and when Sig Burrell finally had to go to a nursing home, the place was sold and chopped up into apartments. From there it peeled and sagged and popped until it had been transformed from a prairie Tara to Laskin’s Bates House and the only reason its windows were still intact was that people were still renting there. I couldn’t remember a time when it wasn’t for sale.

So it was the talk of Laskin just to hear that it had sold. But then we found out it had been bought by movie stars! Ann Koerner! Mabel Pope! Julian Sargent!

“Who the heck are they?” I asked.

“What do you mean, who are they?” Phyllis Nordquist was shocked. “Ann Koerner was in that Lana Turner movie. The one where she kills the millionaire. Or was it Natalie Wood?”

“Lana Turner? Natalie—How old are they?”

Old. But different. Ann—“Call me Annie,” she told everyone in the huskiest voice I’d ever heard from a woman—Annie still walked lightly, easily, quickly. She always wore dark slacks, a white shirt, and one of a variety of brilliantly colored sweaters. Her white hair was always neatly done in a French knot, with bangs, and wherever she went she wore a red beret that exactly matched her lipstick. Mabel seemed far older in her dark dresses, moving slowly and carefully. But then there was her voice, her hair, and her eyes, all of them fluttery and girlish. The pair of them were so complementary that it seemed obvious they were a couple. We knew what Hollywood was like, and we prided ourselves on our sophistication. But then what was Julian doing with them? And who was he again?

Julian, we were told, had been in makeup. Julian had had been in set design. Julian had been a ski bum. Julian had been a surfer. Julian… He wasn’t tall or particularly handsome, but he had silver hair and a silver tongue, and when his eyes fixed on a female of any age, she melted. I watched him at their housewarming work his charm on my mother, who went from skeptical to intrigued to flustered to downright tropical. Granted, she was lapping up Manhattans—a drink no one else in town would ever have served—but no one but Julian could have persuaded her to drink at all in such a public place.

I left them in the dining room and went to the living room, where Annie was outlining her plans to give acting lessons.

“Why not?” she asked. “Half the fresh-faced little ingénues out there come from the Midwest. This way they can get a little training before they go out into the cold cruel world. And I can assure you there is nothing crueler than a Hollywood producer.”

“But Annie could handle them,” Mabel said proudly. Annie held herself a little higher as Mabel pointed out Annie’s name in the movie posters hanging on every wall. “Over here is The Wide, Wide World. Fifth billing, right above Nancy Olson. Queen of Hearts. Seventh, but a very good part, absolutely loads of screen time. Love in the Valley. That was an absolute triumph. Annie played the best friend, who was secretly in love with—Well, you just have to see it. A brilliant performance. There was talk of an Oscar nomination for best supporting actress. Variety raved about her, and the Times said she was a wisecracking Jane—”

“Please!” Annie cried. “As if it was a compliment to be compared to that bug-eyed, flat-faced little bitch.”

“Annie!”

Annie waved her hand, scattering cigarette ashes everywhere, as if she couldn’t be bothered to care.

Later that evening, I had just stuffed a whole giant chocolate-covered strawberry in my mouth—from my fourth plate of hors d’oeuvres—when Annie came striding up to me. I was standing by the windows, in the fond delusion that I was hidden among the drapes, when she said, “Stand up straight. You have the neck of a swan. Show it off.” And she swept off.

It was a wonderful evening.

I don’t know if Annie ever got any acting students—any who paid money. Probably not. It takes a long time for Laskin to trust newcomers, and these three were strange indeed. But a few of us, all early teens, all misfits, quickly became her groupies. There was Phyllis, who lived vicariously through gossip magazines, and a good thing, too, because her parents were so strict, she couldn’t even hang out at the Tastee-Freez. Paul, who was so big and burly that it took me twenty years to realize he was gay. Jean, who was desperately shy. Brian, who was thin and sensitive and a major dork. And me. A couple of others came and went, but they didn’t count.

Annie would let us come over once a week, in the afternoon: “No one who’s ever been in the theater ever gets up before noon, darlings.” Even then, she was always half-asleep, her voice deep and drawling, her breath heavy with smoke and something sweet that Phyllis thought was mouthwash but I knew was gin. But she did put us to work. We read scenes aloud, practiced entrances and exits, sitting and walking, and what to do with our hands.

“Hands are the dead giveaway of the amateur,” Annie would say. “Look at Laurence Olivier or Montgomery Clift. They didn’t hulk around with their hands in their pockets.” She liked to remind us that “ladies don’t pick at their nails.” This one was a goodie: “No, you cannot hold them as if you are in love with yourself. And they’re not dead weights either. They have life! Movement! But natural. Always natural. Even when a thousand people are watching.”

Hands were hard.

Usually, just as we were all dying of frustration, Mabel would come in with pop or lemonade or tea and start talking about Annie’s movies. And then Annie would tell us stories about Hollywood—feuds and casting coups, affairs and tragic accidents, murders and suicides, and endless parties. It would have been more interesting if she’d ever mentioned current movie stars, but we listened raptly anyway. Hollywood was Hollywood, and stars were stars, and it was a leg up on everyone else who didn’t have an acting coach, much less one who had actually attended the Academy Awards.

For a while, everyone was curious about Annie and Mabel. Even my mother pumped me for information about what they wore, what they ate, what they said. But neither of them went out much, and after a while, everyone lost interest. It was Julian who became part of Laskin. He did the shopping and ran the errands. Soon he joined the men for coffee down at Mellette’s Lounge in the mornings. I heard he explained that “the ladies like to sleep in”—he always referred to Annie and Mabel as the ladies—“while I’m more of an early-morning person,” even though no one ever saw him before ten. Then Gladys Johnson got hold of him and talked him into coming to duplicate bridge on Tuesday nights. Soon he was the life and soul of every public entertainment Laskin had, joking and flirting, and so courtly. That was my mother’s word. “He’s a gentleman of the old school. I’d love to know how he got mixed up with those two.”

So did everyone else. But he never spoke about it. Never really talked about Hollywood that much. “The ladies have all the good stories,” he’d say. “I was just grunt labor. Get up early, work hard, go to bed early. Missed all the parties. Oh, I had some fun, but I like this a lot better. Small-town living, good neighbors, clean air. I wish I’d come here years ago. Might have made something of myself.”

At which point some lady couldn’t resist telling him that he seemed fine to her. He was getting quite a following, and things might have gotten sticky, but he always turned down any invitations to private parties. Too busy. Had to run an errand. Promised the ladies he’d do something or other. Always regretful, always wistful, always leaving the would-be hostess with hope.

And then Phyllis Nordquist got pregnant. Mother forbade me, on pain of death, to ever go near Annie’s again.

“But they had nothing to do with it!” I wailed. We’d been talking about putting on a play for months, and I knew that now they finally would—without me.

“Somebody over there did,” she hissed at me. “Something was going on, something you never told me about!”

“But nothing was going on! We just read scenes and practiced—”

“Practiced what?”

“How to…” I stopped. I suddenly knew that telling her that we practiced how to use our hands would not be a good idea. “How to make entrances and exits. That’s all!”

“Well, you’ve made your exit. You’re not going back there. And that is final!”

Poor Paul and Brian were under suspicion, of course. Well, Paul was. No one thought Brian was capable of much of anything. And Phyllis—oh, God, I died just thinking about Phyllis, who’d never say what happened. She was only fifteen, and she’d never had a boyfriend, and it just seemed impossible. Nor did it seem any more possible when a warrant was issued for Julian’s arrest. I really think popular belief would have stuck by Julian—if he hadn’t fled.

“That man violated my little girl,” Mrs. Nordquist said, quivering all over in the dairy aisle at the grocery store. “I just know it. I hope they shoot him when they find him!”

“But…” I began, and stopped when my mother glared at me.

Mrs. Nordquist turned on me and asked fiercely, “Did he do anything to you?” She turned back to my mother. “You’d better have her checked.”

“Nothing happened to Linda,” my mother said through clenched teeth. Then, taking my arm, she spun around and marched us out of there. She raged all the way home: “I can’t believe it! Telling me… Anyone with any decency would have stayed home… But no, she’s out parading around, telling everyone… The shame alone… I can’t believe…”

When we got home, I started to drift away, back to my room. But she stopped me.

“Now you tell me right now, was that man ever anywhere around you kids when you were over there?”

“No,” I cried. “He was never there at all.” And it was true. He’d never been there in the afternoons.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes!”

“If you’re lying to me…”

“I’m not. It’s the truth, I swear it.”

“Well.” Mother had a grim smile on her face. “It’ll be interesting to see what he has to say for himself when they catch up with him.”

But they didn’t. Days went by. Two weeks went by. That was weird. Usually an APB in South Dakota means a quick arrest. Sure, it’s a big state, but it’s a hard place to hide in. Everybody knows everybody else, and they can spot a stranger in a flash. How could Julian vanish so completely? The master of disguise, I whispered to Jean at church. She smiled so quickly only I could spot it.

With Julian gone, Annie took over the grocery shopping and the errands—at a much later hour—driving around in the big old Lincoln with her red beret sticking up above the steering wheel. She acted like nothing much had happened. With the whole town seething, her only comment—to Gladys Johnson, who always rushed in where everyone else held back—was: “Nonsense. It’s just a huge misunderstanding. If Julian wasn’t such a coward… But that’s all Julian’s guilty of. Or could be. Believe me, I know what I’m talking about.” And she actually chuckled as she walked away. That stirred the pot.

Two more weeks went by, and the Nordquists were going to Florida, where Mr. Nordquist had cousins.

“It’s just been so hard on all of us,” Mrs. Nordquist announced, this time from the toiletries aisle. “We’ve told Sheriff Hanson to call us and we’ll fly back at a moment’s notice to put that monster away. But we all need some space. Some rest. A change…” And she picked up a bottle of aspirin and went to the cash register.

“Well,” my mother said, “Phyllis won’t be pregnant when they come back, that’s certain.”

“So that’s where they go from around here,” Annie commented as she wheeled her cart up next to ours. She was looking at the checkout aisle, where Mrs. Nordquist was fumbling around in her purse. “This farce has gone on long enough.”

“Well, if you know where he is, I suggest you get him back at once,” my mother snapped back.

“Oh, I’ll do more than that,” Annie said, and swept away.

And the next day, Julian was back. He went to the police station and turned himself in. The Nordquists could hardly run fast enough down there, and they weren’t the only ones. It was amazing how many others managed to find some reason to be downtown. My mother, for example, decided she had to pay the electricity bill right then, though she usually just mailed it in. So there was quite a crowd on hand to find out, a few hours later, that Phyllis had finally talked and Mr. Nordquist had been arrested for Prohibited Sexual Contact.

“Incest!” Gladys Johnson gasped.

“What about Julian?” Mother asked.

“I can’t believe it. Homer Nordquist?”

“Poor Phyllis.”

“What about Alva? Do you think she knew?”

“Oh, of course not.”

“Poor Alva. And they were going to Florida.”

“But what about Julian? How do they know—”

Chief Munson came out, looked at the crowd, and shook his head. “Folks, why don’t you go on home?”

Nobody budged. Instead, a flurry of questions rose up, all of which he ignored, except my mother’s: “What about Julian?”

For once in his life, Chief Munson cracked a smile. “We have proof that Julian Sargent is innocent of any and all charges.”

And they did. When Julian turned himself in, they searched him before putting him in a cell and discovered that, technically speaking, he was a woman.

Alva and Phyllis Nordquist went to Florida and never came back. Mr. Nordquist got sentenced to five years. Judge Bolland decided he couldn’t give such a “decent citizen” the maximum of fifteen, and Homer ended up serving only three. When he got out, he moved away. Nobody cared where.

As for Annie and Mabel and Julian, they stuck it out in Laskin. For a long time, everyone felt a little awkward around Julian. But after a while, everyone thawed, and soon Julian was again the life and soul of every function. He was just so much fun. And yes, we kept referring to Julian as he. Like I said, we’ve always prided ourselves on our sophistication.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This story is based on a silent-film actress and her two companions who moved into a house across from my childhood home in Escondido, CA (which was full, by the way, of retired film actors because, back then, it was cheap and not that far from Hollywood). She gave me “acting lessons,” which were mostly talking about old film stars (Ramon Novarro, Tyrone Power, etc.). Tallulah Bankhead was a friend of hers, and I met her for like, one minute. Amazing woman, with a voice like a foghorn.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Eve Fisher’s stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, Black Cat Mystery Magazine, Mystery Weekly, Crimeucopia, The Bould Awards, and elsewhere. Three of her AHMM publications have been honorable mentions in TheBest American Mystery Stories2012 and TheBest American Mystery and Suspense (2022 and 2023). She blogs biweekly at sleuthsayers.org.

A KILLER VIEW,by Joslyn Chase

Emma Watterson stopped tapping at her keyboard and chewed the cuticle of her right index finger as she stared out over the darkening skyline of Seattle. The faint wail of a siren, thinned almost to wind-chime quality by distance and plate glass, caught her attention and she shifted her gaze to the streets below, watching the flashing lights of a police car as it wove through congested city blocks on an errand of public safety.

Emma loved this view of Seattle from her high-rise above the city. Lights shimmered on the Sound, from cruise ships parked along the pier and the Bremerton ferry puffing across from the Kitsap peninsula. At the far right of her windowed vista, she even had a view of the Space Needle, if she moved to the very edge of the sofa and craned her neck.