Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

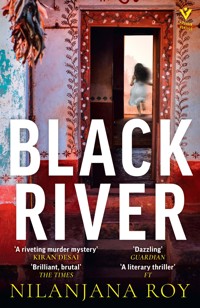

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

It takes a village to kill a child...The village of Teetarpur outside Delhi, is famous for nothing until one of its children is found dead, hanging from the branch of a Jamun tree. In the largely Hindu village, suspicion quickly falls on an itinerant Muslin man, Mansoor.It's up to the local policeman Sub-Inspector Ombir Singh to get to the truth. With only one officer under him, and only a single working revolver between them, can he bring justice to a grieving father an an angry village - or will Teetarpur demand vengeance instead?This shockingly powerful literary thriller is set in a brilliantly realised modern India simmering with tension and riven by growing religious intolerance.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 452

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Tarun Roy (1939–2021) father and friend who always let me raid his bookshelves

Contents

Teetarpur, 2017

Blight

Munia’s eighth birthday falls on the hottest day in June, with the smell of burning cane scenting the air. She forgets the heat in her excitement over the slice of cassata her father has brought all the way from Teetar Bani, the main town. Chand had ordered the precious gift from the only shop in the town that possessed a freezer, and carefully packed it in a tin pail filled with jute sacking and ice purchased from Raju Golasharbatwala’s cart.

The cassata melts, a puddle of bright colours. She eats it slowly, bending her head to the dented tin plate and lapping up the last delicious drops of strawberry. It is a rare taste, a flavour she has not encountered before. Her father asks, ‘One more slice?’

She nods, but halfway through, she holds out her plate to Chand, presses the spoon into his hand. ‘You also eat. One spoon for you, one for me.’ He takes tiny bites.

There is nothing Teetarpur is famous for. The older residents say proudly that their village is not known to have inspired a line in a film song or even a mithai, has never produced so much as a celebrity or a famous politician. They cherish its anonymity, though the younger generation would have preferred a more rousing history.

Chand’s hut, and his brother Balle Ram’s equally modest establishment, are almost the last houses in the village. They are set on a slope just before the soaring forests arc upwards on the first hill of the Aravalli range. A canal flows behind Chand’s home, opening out onto untended fields.

Their huts are about an hour’s walk from the tumbledown police chowki that marks the start of Teetarpur, a fifteen-minute ride on Chand’s ancient Rajdoot 350cc bike. In their boyhood, the two huts were part of a dozen-strong cluster, but most of their neighbours had moved to the village proper, disliking the isolation, the dark shadows cast by the forest at night.

Balle Ram and Chand stayed on after their father’s death, unwilling to abandon their ancestral land. Chand plants a few food crops in the field near his hut and leaves the trees to flourish as they please. Balle Ram and he reap fair harvests from their other fields, which are a long walk away, part of the patchwork of village lands that lie behind the police chowki.

Chand’s only other neighbour is the richest man in Teetarpur, Jolly Singh, who brings some of Delhi’s briskness with him. Jolly Villa rose brick by brick fifteen years ago, its brightly painted gates and balustraded roof one of Teetarpur’s wonders. It rests like a gaudy crown on a low ridge, looking down at Chand’s hut and the village below.

In the mornings and early evenings, pilgrims pass by Chand’s hut to pray at the shrine of an animal-loving sage who lived high up on the first of the great hills of the Aravalli range. But they are otherwise undisturbed. During the day, only peacocks and snakes travel up the hill to the quiet shrine.

Chand has grown to cherish their isolation and independence, though he tells Munia many tales of Delhi, of other faraway places they find in her school atlas—the Arabian Sea, the winding silver ropes of the Yamuna, the Ganges, the towering snow-covered ranges of the Himalayas. She has hazy memories of the capital, which she had visited once with her father when she was just five years old.

‘An ocean of cars and a sea of houses,’ Chand says to Munia. ‘At first you put your hands over your ears because of the noise from the traffic, but you liked Delhi after a while. We’ll go again, someday.’

‘But I like it here the most,’ she says firmly. ‘I don’t want to go anywhere else.’

‘When you’re grown up, you’ll want to see the capital. Everyone does.’

‘I want to see the Himalayas.’

And Chand says, delighting Munia, ‘Some day we’ll take the Rajdoot, you and I, and we’ll go all the way to the mountains, you’ll see.’

Chand’s fields, the trees and the mehendi bushes that surround them, are set down from the road, hard to see even from Balle Ram’s home. Chand knows that when he leaves to farm his other fields, this small patch of earth becomes his daughter’s private kingdom.

He has seen Munia whirr across the ragged green carpet of the cowpea fields when she thinks no one is watching. Her thin, sunburnt arms, speckled from the sun, and bare feet put him in mind of the tiny brown bird she’s named after.

Munia is quiet with strangers and with family, rarely speaks in front of Balle Ram or his wife Sarita. She is an explorer at heart, fond of illicit excursions, absorbed in the games she invents, and plays with birds and insects.

She talks only to her father. Him she tells everything, the conversations she overhears, stories she has made up. Her piping words patter as rapidly as monsoon rain against a thatched roof. She tells Chand about the four men hanging at a steep angle off bamboo scaffolds that appear to be anchored in the sky itself, stringing long ropes of lights like twinkling green stars in Jolly Singh’s massive farmhouse, and about the new carp pond there, gleaming with fat red-and-gold fish. About the bus that collided with a truck at the crossing up ahead, both drivers unwilling to be the one who braked first, and how the loosely packed sacks of marigolds, the truck’s cargo, had burst and spilt in an orange river across the road.

That time, she had carried one of the marigolds back home to show him, allowing him to cradle her in his arms as he inspected the small, crushed petals. ‘You smell of woodsmoke,’ she had said to him. ‘I smell of mud and sweat and dirt,’ he had replied, but his daughter was already asleep, her head a tired smudge against his checked kurta.

Every summer, the heat grows more fierce. The dhak trees in the forests that the villagers have protected and held sacred for centuries shrivel in this furnace. Even the peafowl that roam the slopes are too listless to call out to each other, and the silence in the forest settles heavily around Chand and Munia.

As the temperature soars, the red rot spreads across Chand’s land. The blight races from field to field, no matter how diligently the farmers of Teetarpur uproot the infected clumps of sugarcane. The stench—fermenting, gangrenous—rides across the fields along with the smell of burning crops. Bugs fatten on the spoils and white grubs scuttle out of the way of the flames, fastening onto new stands. The rot takes hold easily, the land smoulders.

Smoke from the cane fires hangs thick and acrid over the village. Chand has to leave Munia behind when he sets out to tend his sugarcane fields. He ignores his daughter’s pleading eyes, even though it’s her birthday week, gently turns down her soft demand to be carried there on the high throne of his shoulders, to be included as an essential part of his working life.

Chand tells her, ‘You’re eight years old—all grown up now. Don’t give your aunt any trouble while I’m away. You promise?’

She nods reluctantly.

Munia’s silent prayers work. Her aunt leaves to collect wood for the stove. In a flash, she is out, exploring.

The sun leaves thorny prickles on her skinny, bare legs as she steps into the cool grey mud where her father had watered the plants that morning. She likes the way it squishes up between her toes, a friendly massage from the earth. A strip of sun-baked earth, powdery and ferociously hot beneath the soles of her feet, spans the gap between the bund and the neem and jamun trees. The thin silver chains of her anklets set off a faint carillon as she fits one foot, and then the next, into the wide cracks in the scorching earth. She shudders at the delicious change in temperature, the coolness secreted away deep inside the furrowed land.

Placing her cheek against the bark of the trees, she feels the difference between smooth bark and scaly bark, the texture of each tree as singular and well known to her as her own family’s faces: her uncle’s rich dark skin, her aunt’s papery, delicate skin, the comforting touch of her father’s rough-skinned, gentle fingers.

She walks warily over the fallen nimbolis, careful not to tread on the green berries, hard as stones. It is quiet in the orchard, with no spring breeze to cool the air, only the first heavy stirrings of the summer heat rising up from the dust. A worker’s scaffold, the shape of a swing, lies at the foot of the tree, anointed by a thick coil of rope. A leftover from the construction on the Lovely Pure Veg Bhojanalaya. She has seen her father use it to repair the roof thatch.

She ducks beneath the jamuns. Their slender, long-fingered branches reach out and brush her tangled, sun-browned hair.

Munia has plucked a skirtful of berries when she sees the man. He is in the nearby plot, leaning back against the makeshift planks of cart wood that wrestle the thorny bushes into a low fence. Strangers rarely come through these parts. There is nothing to tempt them in this untended plot of common land that separates the fields from the forest soaring above. But this man is no stranger.

The heat dries out the sugarcane leaves. They thrust upwards into the sky, black against the harsh white glare. Chand squats in the mud, sees the grey mould sprayed across the sugarcane stems, the bruises on the stands of cane. Inhales the sour, fermented air, the kind of stench that rises off the skin of alcoholics drunk on the hooch sold in plastic packets up and down the length of the state. The exhalations from the sugarcane on this side of the fields seem almost human. He probes the stem with his cane knife.

The stem splits easily. Inside, there’s discolouration, and Chand has to turn away, take a breath of fresh air before his nostrils inhale the red rot again. He sights along the line, along the stands. An untrained eye would see little—just a hint of grey fuzz on the stems, a few black spots here and there. But he knows what he will find inside: red bruises, maroon discolouration. The damaged cane reminds him of the fragility of pulped flesh and broken bones. He brushes the thought away.

Chand stands at the edge of the fields. He is covered in the dust scattered by the wheels of trucks on their way to the stone quarry, masking the summer tan of his skin, turning him into a ghost. The trucks link Teetarpur with the brisk rumble of the new industries springing up around the Aravallis, and the elongated mansions where they grow only trees and flowers but no useful crops.

From the stench across the embankment, Chand guesses that many will have no sugarcane crop at all. This, in a year when many of the villagers have been selling their land, some for money, some because their children no longer want a life tied to farming.

Chand walks home as swiftly as he can, ignoring the scorching sun, harsh on his back. Munia hates it when he stays out in the fields too late. She likes to tell him about her adventures, real and imaginary, in these quiet evening hours. The sweat pools and prickles between his shoulder blades, and he quickens his step, glad to be returning to his daughter.

The Man in the Field

Munia considers the man gingerly, as she would assess a battle-scarred bull monkey for malevolent intent.

He closes his eyes and wipes the sweat off his brow with a cotton scarf. Not a local red cloth but a fancier printed city towel. He tips his head back, his eyes closed.

Munia inspects the jamuns gathered in her skirt. They are squashed and not as purple as she likes them to be, but when she cautiously bites into one, the flavour explodes on her tongue.

She looks over at the man. He has his eyes open, and his head tilted, and he is watching thick grey puffs of smoke from the chimneys of a faraway brick kiln drift by across the blinding hot blue of the sky.

The girl shuffles back through the cool, sticky mud, holding her skirt like a bag around her knees. The munias start to call, their high, plaintive voices plinking far above her head.

She hears a laugh, the rustle of long skirts over the scrub and rock, and looks over, losing her fear. Munia understands illicit meetings. She is a brown scrap, so easily overlooked. Hidden in the branches, she has seen lovers come up to the mandir, taking selfies, seen them look around and go behind a bend in the road.

The jamuns, sun-ripened, fill her mouth with sweet, purple juice. The man stretches and leans towards the woman, swinging her around lightly so that he stands facing in Munia’s direction, the woman’s back to her.

‘You never have time for me these days,’ the woman says. ‘Is it the factory that keeps you busy or is it those famous sluts from your infamous city?’

‘Too much work,’ the man says.

Her voice hardens, business-like. ‘Did you bring it?’

‘Yes,’ he says. ‘But later, no? First some masti.’

She says, ‘The full amount?’

‘What you asked for. Yes, I brought it. But no more after this, okay?’

She says, ‘First you beg for a taste, then you don’t want anyone to know what you’ve been sticking where. Don’t worry, baba, I won’t tell anyone about us. You can run back to your family and pretend you never met me. Wait, I’ll do it, don’t rip my blouse, it’s new! You’re so impatient!’

‘You’re so tempting,’ he says. ‘And we’d better be quick. We might not be easy to see from the main road, but someone could take a shortcut along the canal and spot us. You like this? And this?’

Munia glances idly at them, admiring the woman’s tight pink-and-green blouse, the silver ribbons she has plaited through her thick, long hair, the vivid patchwork green of her swinging lehenga. The woman has her head down, shy, but the skirt is bolder. It swings towards the man and strokes his ankles, then he moves a hand, and magically, the skirt lifts, higher and higher, and Munia hears the woman gasp as the man’s hand disappears under the bold, flirtatious lehenga, which is rucked up to her waist now.

The sun is directly over the man’s head, but she is close enough to see him close his eyes, and she watches, casually interested. The woman is shuddering, her long hair in disarray, still moaning, still murmuring endearments.

He raises his head and looks in Munia’s direction. She doesn’t think he has seen her, but she shrinks back, just in case.

The man removes the gaudy towel from around his neck. It is patterned in browns and purples; shimmering butterflies, their outlines shaky, their eyes a glaring orange, are printed in vivid deep dyes across the length of it. The colours—the strutting blues, the garish golds—dance before Munia’s eyes, even at that distance. She watches in fascination as the man uses one hand to twist it into a rope, expertly, stroking the woman’s hair with his other hand.

He twirls the towel. The colours go round and round, a rope of blue and gold butterflies. The woman looks up at him, and he slams the flat of his hand across her windpipe. Munia hears the choked-off beginnings of something that might have been a scream, and involuntarily raises her own small hand to her neck. The woman sags to one side, like a sack of crumpled clothes for the dhobi, and the man moves with swiftness, slipping the towel around her neck so gently that he might be garlanding her.

The woman sighs loudly, breath leaving her body in a long exhalation, her generous bosom heaving, and Munia recovers from her fright. It is a game between them then. The butterflies flash in the sunlight, dancing. The man kneels beside the woman, his hands moving deftly.

Munia can see him looking with tender care into the woman’s face. Then he laughs and picks her up like a bundle, something darkening at her throat. Her long hair flutters over his elbow like a flag. He carries her down, weaving through the scrub, out of sight, towards the straggling dhak trees.

A pair of green bee-eaters settles on a low branch, and Munia stretches up to watch them. One of the pair has caught a wasp, and it dashes the insect against the bark, smashing the wriggling yellow creature until it hangs limply from the bird’s beak. Chand had once told Munia that bee-eaters are cleverer than people. They take the sting out of the wasp, just like he carefully extracts the rough stone from mangoes with his thin-bladed knife before giving the fruit to his daughter to devour.

Munia turns to go back home.

The man is right there, smiling, squatting so that he looks straight into her eyes, the towel slung carelessly around his neck. He has circled around and returned.

‘Were the jamuns sweet?’ he asks. ‘It’s all right, you can talk to me. I know your father, and your uncle, Balle Ram.’

Munia relaxes. The man speaks differently from them, his Hindi smooth and citified. But he has the soothing tone of a person used to gentling startled animals, or shy children.

‘You’re not scared, are you? I think you’re too grown up to be scared of anything,’ he says, voice pitched low. ‘Only small girls get scared. You’re a big girl, aren’t you?’

Munia nods, a quick, bird-like movement of her head.

‘If my friend was here,’ the man says casually, ‘she would have given you a toffee. You saw her, didn’t you? The woman who was with me?’

The girl nods again. She looks hopefully at the man, who smiles, and like a magician, pulls out a fistful of coins. Her eyes widen.

‘Which ones do you like?’

She points to the ten-rupee coins.

‘And this?’ he says, bringing out a five-rupee coin.

She wavers. The ten-rupee coin is worth more, she knows that, but the five-rupee coin is shinier, prettier.

‘Here,’ he says, before Munia can decide, ‘take them all.’

She holds the coins in her hands and closes her eyes, feeling each separate one like a treasure.

‘Do you like swings?’ he asks her. At last, she smiles.

‘I can make good swings,’ he says. ‘When I was a boy, we used to make rope swings and tie them to the branches of trees. Have you seen that type of jhoola?’

Munia shakes her head, no.

He picks up the scaffold and expertly tosses the long, fat coil of rope over the thickest part of the branch. Glances around to check, but they are alone, the man and the girl, invisible from the road. He makes a double loop and beckons Munia closer. She comes up, clutching her precious coins in both fists.

‘That’ll hold,’ he says, pleased. ‘That’s done the trick.’

He produces a handkerchief, a striking navy blue. Ever so gently, he prises the coins out of her hands, ties them in a bundle, ties the corners of the handkerchief to her skirt. ‘There,’ he says. ‘So that they don’t fall out.’

She crinkles her eyes, not seeing a swing yet. ‘This is how you make a swing,’ the man explains as he kneels on the ground. ‘You tie a thick knot and then you make a loop. Come, I’ll show you.’

She draws a circle in the dust with her left toe, suddenly shy. Then she makes up her mind and steps towards him, putting up her purple-stained hands, allowing herself to be lifted onto his knee, watching as he knots the rope. ‘It’s a shame,’ he says softly. ‘That you were playing here today. That you saw.’

He gives her a tight, encouraging smile. ‘Swing, little one. Swing.’

Munia in the sunlight, smiling up at the man, the noose around her thin, unresisting neck. The peacocks take wing, vivid green streaks over the trees. They are finally calling, three-note shrieks that rend the air, but there is no one to hear.

The Weight of Rope

A sound draws him to the back, that is how he finds her. As he is about to step into the hut, Chand hears a man sobbing, such an unexpected sound. He jams his tired feet back into the worn leather of his jootis and goes around to check.

He sees a bundle hanging from a tree limb like a discarded shawl. The sun is directly in his eyes, its white light blinding, black shadows and shapes shimmering when he blinks. A second huddled form on the ground. Sweat in his eyes. He blinks it away.

Then the disparate shapes, the harsh sobs, come together, like one of those puzzles they sell at the fair, where black cardboard pieces suddenly come together to form a bird, a star. Or a tree, a girl with a rope around her neck, her feet dangling far above the earth, hanging from the jamun’s thickest branch.

He tries to call her, Munia, Munia, but his mouth is dry from shock and from the heat. He forms the syllables of his daughter’s name and whispers it into the heavy air.

A man kneels on the ground, his white salwar streaked with dust and mud, holding on to Munia’s limp feet, crying like a child, his breath rasping and hard.

The girl’s eyes are closed, her lashes resting lightly on her cheeks, purple stains on her curled fingers. She could be holding her breath, except for the tilt of her neck, the coil of rope, the swing dangling at a crazy angle, a heavy wooden counterweight.

She will open her eyes, her father thinks, she will smile at me and put out her arms to be helped down, and then I will carry my Munia inside one more time.

The man in his torn white kurta, his mud-streaked salwar, puts his hands to his head, keens, a long, low sound. When his elbow hits the child’s feet, she spins slowly, turning in a wide circle, her toenails ringed with dried mud. Chand sees the livid discolouration around her neck.

The man begins to crawl towards him on his knees. It takes a moment for Chand to recall his name: Mansoor Khan. He had wandered into their village some months ago, one of the drifters who sometimes passed that way in search of shelter.

A quiet man with pain-filled eyes, dignified and private. He carried a bag of carpentry tools, but was not fit to work. He often wrapped his hands in cheap white muslin to cover some old injuries, the frayed ends of the cloth giving him a spectral air. From time to time, he walked with a purposeful tread around the fields, muttering gibberish rhymes to himself. He survived on alms and the kindness of the local farmers. Chand too had put small packets of atta and dal, tea leaves and crumbling brown molasses in Mansoor’s frayed cloth bag, as they did with holy men and the occasional harmless lunatic.

Mansoor is plucking at his sleeve, saying, ‘Chand, Chand, I didn’t do it, I was crossing your fields for the shortcut. I did nothing, I saw her hanging in the tree, it wasn’t me, it wasn’t me.’

Chand slaps his hand away, can barely make sense of Mansoor’s babbling. ‘I have to get that rope off her neck, it’s too heavy for her,’ he says.

He can’t take his eyes off his child, her small body slowly twirling like one of those painted wooden puppets from Rajasthan, dancing at the end of a string. The sun beats down. He is shivering.

Night Duty

Ombir Singh feels a red, throbbing knot of pain tightening at the back of his skull. Twenty hours is normal, thirty-six doable. He’d once gone seventy hours without sleep: noises sharpened, colours brightened till they were painful, the floor and the roof swung around him.

Forty hours since he left the Teetarpur station house in Bhim Sain’s charge, and he hasn’t managed even a short nap. Sweat and dirt stiffen the collar of his uniform, his back muscles are on fire from the long ride on his Bullet to Faridabad and back.

He shoulders his fatigue like a heavy, familiar backpack and steps inside the station house. The evening is falling swift. Inside the station house, two hurricane lanterns cast a warm glow over the register, and lizards scurry up the painted brick to the straggling thatch of the roof. Outside, sequestered in the pound, he hears the hobbled cattle snort, adding their odour to the ammoniac smell rising from the grey gutter that bisects the thana’s main room.

Bhim Sain is asleep at the desk, his head resting on the pages of the station-house register, his jowls sallow and sagging like an old dog’s. A strip of his heart pills have fallen out of his pocket to the floor. Near his outflung hand, Ombir sees a paper plate rimmed with leftover grease from the pakoras he buys by the dozen from Lovely Bhojanalaya. Ombir slides a hand under Bhim Sain’s cheek, lifting his jowls an inch so that he can extract the register, then places the sub-inspector’s head gently back on the rough wooden table that serves as their desk. He will take an hour to catch up with the paperwork. Then he can wake Bhim Sain, get in the four or five hours of sleep he has been craving all day.

Ombir is scrutinising the day book when he hears the bike. Bhim Sain’s snores stop—the sub-inspector is able to cross from deep sleep into instant wakefulness at the first hint of a disturbance. The engine skips a beat from time to time, and Ombir recognises the arrhythmic signature of Dilshad Singh’s sputtering Yamaha.

By the time Dilshad arrives, Ombir is at the gate, raising his torch in the twilight so that he can see their visitor’s face more clearly. Green-eyed, his face and stylish beard as chiselled as any film star’s, the young man moonlights as a police photographer. He had honed his trade taking portfolio pictures for women who were determined to make it some day as local pop singers, and wedding troupe dancers who posed as deities for calendars or as porn stars for the cheaper magazines. The work sharpened his eye for detail, made him useful at crime scenes.

‘Thank God you’re back,’ he says. ‘What a calamity! They’re all there, I told them they must wait until you two reach.’

Ombir says, ‘Wait. Take a deep breath. Calm yourself down and then explain properly.’

‘Chand’s daughter has been murdered. I took photographs before Balle Ram and he brought her down from the jamun tree. And they’ve caught the murderer already.’

Ombir says, ‘Munia is dead? The little one?’

He has known Chand for many years, and was glad to see him return from the big city to his family and his lands eight years ago. Every morning, if his work isn’t too demanding, Ombir walks the length of Teetarpur village, and up the main road towards the forests. The village lies at the edge of the Delhi–Haryana border, an hour’s drive down silent, forested roads covered in powdery summer dust. Its soul has remained half a century behind the capital. Delhi’s frenetic, relentless activity is not to the taste of most of Chand’s generation of villagers.

Meanwhile, Teetar Bani grows steadily, like a concrete wasp’s nest, sandwiched between the highway and the stone quarries that stubble the rolling hills, the first swell of the Aravalli range. The village, Teetarpur, is over a hundred years older than the town, but much smaller and set farther back from the highway, close to a belt of sugarcane factories and oil mills. It is a modest settlement of barely two hundred huts and single-storey brick homes.

The brothers’ huts are at the far end of his beat. He has watched Munia grow up, become a quiet child with large, curious eyes who kept to herself.

A memory from two days ago: the girl watching him solemnly as he went about his rounds. He had gone up towards Jolly Villa, and when he came back, she was imitating a policeman’s slow, deliberate walk. He had laughed. She stopped, stricken to be noticed, then gave him a shy wave before running away.

‘We’d better get there before they take matters into their own hands. Who’s the bastard who did this?’

‘Mansoor,’ Dilshad says.

Ombir frowns, and Bhim Sain says, joining them, ‘Must be some mistake. Mansoor wouldn’t harm anyone. And why would he hurt Chand’s daughter? They used to let him sleep in the field some nights, gave him tea, and a meal also.’

‘Mistake or not, we should hurry,’ Ombir says, kickstarting their unreliable Bullet. ‘Angry men don’t stop to think.’

The flaring light of petromax lanterns illuminates the scene. Mansoor kneels on the ground, his white kurta torn, his black salwar streaked with dust and mud.

Balle Ram and a score of villagers surround him. In the centre, Chand, bowed over the body of his eight-year-old daughter. Dust on her skirt and face, livid rope marks where the noose has slackened on her neck. Ombir looks around—fifteen men already, some with scythes, others with axes. And he and Bhim Sain with only one revolver between the two of them, because Bhim Sain’s revolver is with the gunsmith for a faulty front sight.

Chand’s brother is the one to handle, he decides. If he can calm Balle Ram down, he has the crowd. If not, his record will show that he couldn’t prevent a village lynching, and that might hold up his overdue promotion even longer. He is relieved when Bhim Sain does the right thing. The sub-inspector kneels by Chand’s side, gently puts a hand on the man’s shoulder, speaks a few words of comfort.

Ombir holds up his hand for silence. The crowd quietens, its attention held by Balle Ram and Chand, grief softening the edges of vengefulness in the atmosphere.

Balle Ram steps forward. ‘This is our business, Ombirji. Not yours. This man came into my brother’s fields, he killed my niece, he took her from Chand. Leave him to us. I told Dilshad not to interfere.’

Ombir says, ‘Where was she found?’

Balle Ram points to the jamun tree.

‘I have photographs,’ Dilshad calls.

Ombir scans the ground rapidly, playing his torch over it, his heart sinking. Of course Chand’s family and the rest of Teetarpur would have crowded around without a thought to footprints or any other signs left behind by the murderer. He will have scant evidence to present. And even if Mansoor confesses, the courts rarely trust a prisoner’s confession without eyewitnesses to the actual murder. So easy to beat one out of a man.

He flashes the light full on Mansoor’s face. Usually, Mansoor has a gentleness about him. Ombir thinks of him as one of God’s children, one of the imperfect pots baked from the Almighty’s clay, with a crack running through. In Teetarpur, he had received the respect due to all madmen, until this day.

The man whimpers. Ombir holds his torch steady, letting them see what they’ve done already, the bruises rising blue and livid on the carpenter’s skin, the blood dripping from his forehead onto his kurta.

‘And who found him?’

Chand raises his head. His deep-set eyes are filled with stunned anguish, his face gaunt and lined.

‘He was clasping her feet when I arrived,’ Chand says.

‘Your daughter was already dead?’

‘Yes.’

‘He didn’t try to run away when he saw you?’

‘No.’

‘Did Mansoor say anything to you?’

Chand blinks, recovering himself with an effort. ‘He said he’d taken the shortcut and seen her. He said he didn’t kill my girl. He was crying.’

‘He’s a madman,’ Balle Ram says. ‘They don’t behave the way we do.’

Ombir looks around at the men and says, ‘Please lower your weapons. Give me one chance to settle this. We also knew Munia. We also care about Chand. I know him personally. Only one chance, that is all I ask.’

Bhim Sain picks up the cue. ‘Give them some space,’ the sub-inspector tells the gathered men. ‘I want photographs of the area without all of you crowding around. We’ll need them for our files.’

Two more men arrive in a tempo, carrying thick slabs of ice covered with gunny sacks against the heat. Ombir is glad for the distraction. Bhim Sain organises some of the men, helps them carry the slabs into Chand’s hut.

Ombir feels Mansoor’s trembling hands clutching at his ankles. He ignores the man, pulling away. If at all he can help it, Ombir doesn’t want to draw the crowd’s attention to the poor lunatic. He sits down on the ground, a few paces away from Chand, and motions to Balle Ram.

The man hesitates, then reluctantly walks over and sits down. One small bit of ground gained: always cut the leader off from the mob. Ombir can speak more privately despite the circle of watchers.

‘For almost three years,’ he says, keeping his voice so low that Balle Ram has to lean towards him, ‘I came by this way, passed your brother’s hut most days. I saw your niece grow up. She has been taken from all of you in the most cruel way possible. Balle Ram, Chand had his daughter, and he had you. Now he has only you. My question is, will you help him or make it worse for him?’

‘How can anything be worse than this? She was ours, too. We loved her like our own daughter. My wife—she’s at home, she can’t even speak without breaking down.’

‘Yes. And it would be the easiest thing in the world for me and Bhim Sain to leave this man with you tonight.’

It’s the truth. All he has to do is not file a report, to warn Dilshad that, for the official record, he never took any pictures, never came to the station house. He could so easily look away while their rough justice takes its course. But questions may be asked. The paperwork will come around to him, in time. And there is one other matter, a minor detail but important to him, which he wants to turn over in his mind later.

‘Why are you wasting time, Ombir-ji? Give him to us.’

‘Because of Chand. For his sake.’

He waits, but Balle Ram is silent and confused.

‘The man has lost his child. In the heat of this moment, he and you could do anything at all. No one in the village will question your right. But the murder of a young girl—it’s not so easy to cover up. It hasn’t happened before in Teetarpur. Drunks and junkies, pimps and whores, their bodies turn up from time to time. This is the first time that one of our own has been killed, that too in such a terrible manner. Look around you. There are too many people here tonight. If it was only you and Chand—well … That might have been different. But this is a sizeable crowd. Someone will talk. They promise they won’t, but they always do, and then what? Then this case won’t be handled by us, Balle Ram, it’ll be handled by the CID.’

Balle Ram says, ‘What do we care? Let them come.’

‘You don’t care? When it’s over, when your brother can’t mourn in peace because there is an inquiry, when policemen who don’t know the two of you drag him away to the big station in Faridabad to ask questions, you’ll care. If there’s a court case, you’ll care. Is he in any shape to manage all of that? Think, Balle Ram, set your own loss aside and think. You are all your brother has left. Will you protect him, or will you shove him into harm’s way? I can’t protect him once there is official involvement.’

He waits, lets his words sink in.

‘And the department will be involved. Chand’s home is next to Jolly-ji’s farmhouse. There will be a thorough investigation. Balle Ram, please try to understand. I cannot let anything happen until Jolly-ji himself is made aware of this terrible situation, but I am with you. I will stand with you and Chand. All I ask for is time. Only two weeks.’

Balle Ram shakes his head, bewildered. ‘Two weeks? For what?’

‘Allow me to conduct an investigation. If they send officers from Faridabad, I’ll be able to manage it. We’ll make sure we find out if it’s Mansoor who did it or—’

‘Chand shouted out for me, I came running. We both saw him, how can there be any doubt?’

‘I don’t doubt you,’ Ombir says, soothing the man. ‘But I have to be certain. It’s the law. Give me just a handful of days, Balle Ram. After that, I promise, you will have your justice.’

‘Where will you hold Mansoor?’

‘I’ll make sure he’s held right here, in our lock-up.’ Ombir is fairly certain that this will be the case. The central jail and the district jail are both overcrowded, and it will take time to arrange the prisoner’s transfer.

‘All right,’ Balle Ram says. ‘But only one week, not two. After that, no matter what you say or what the law might do, he is ours.’

‘One more thing,’ Ombir says.

‘What?’

‘Munia. We have to take her body to the morgue.’

They both look at Chand. His craggy face is almost serene. He holds his daughter to his chest, his eyes closed.

‘Tomorrow morning,’ Balle Ram says. ‘Tonight, let us take care of her.’

Ombir gives in. He has Mansoor, he’ll see to the rest later.

Watched by the knot of men, Bhim Sain helps Mansoor to his feet, makes him hold out his shaking hands, takes him formally into custody.

‘It wasn’t me,’ Mansoor says suddenly. ‘Chand, I would never hurt the little one.’

‘Get on the bike,’ Ombir says. He tells Bhim Sain to tie Mansoor securely to him, and to follow on the back of Dilshad’s Yamaha.

The Bullet roars to life, chugging fitfully. Mansoor Khan feels the handcuffs, tries to shake them off, submits. From time to time, he jerks his wrists, like a cow attempting to flick away flies. But he seems to feel protected by Ombir Singh’s presence, calms down as the bike leaves the mob behind.

At the station, Ombir leads Mansoor Khan to the grey-painted storeroom at the back of the thana. He places an earthenware ghada of water on the floor, a steel tumbler, then brings in a charpai, its coloured strings sagging.

‘Sleep, I’ll bring you some food later,’ he says. ‘If you have to shit or piss, call me. We won’t make you do it in here.’ He places an empty Dalda tin under the cot, just in case the suspect needs it.

In the station house, he listens to Bhim Sain giving the Faridabad station-house officer a full report. Ombir pushes away thoughts of sleep, buzzing at him like insistent mosquitoes.

His eyes close briefly even so, against his will. And the image of Mansoor’s hands returns, demanding attention. He had taken a good look at them twice, once when the man was on the ground, once when he had got onto the bike, his feet slipping off the guard. There were a few drops of blood, presumably Mansoor’s own, on the gauze that wound around his hands. But nothing else. No bark, no dried leaves, no twigs, no purple stains from the jamun berries, nothing to testify that he had indeed touched the tree or the girl. It doesn’t prove anything, but it does arouse Ombir’s curiosity.

From behind him, Bhim Sain says, ‘They’re taking the case seriously. I spoke to Bhadana also.’

‘Jolly-ji’s manager? Is he here?’

‘No, he’s returning tomorrow, and Jolly-ji himself will return as soon as he can. They said he’s attending to business in the city. But Bhadana promised they would give us all the help we need, and the SHO at Faridabad said they’d send an officer. A big officer, top one. Haryana cadre, but my friends say he grew up in Delhi and has uncles in politics over there. He’s not like us.’

Ombir stares at the worn desk. ‘When does he reach?’

‘The day after tomorrow,’ Bhim Sain says. ‘First thing in the morning.’

Ombir wishes he could put his head down and sleep until the Delhi boy arrives. But a day is very little time.

‘Suspects,’ he says. ‘We’ll need more suspects.’

Ombir takes a sip from the glass of water. It tastes stale and foul, as if a lizard has pissed in it. ‘There was only one clear footprint at the base of the tree. From a fancy shoe, not from a plain jooti, not chappals or sneakers. No one out there tonight was wearing that kind of shoe. And Mansoor’s hands, his bandages—there wasn’t a shred of bark from the tree on them.’

‘Are you saying he didn’t kill that poor girl?’

‘What do I know? Maybe he goes around the country pretending to be mad and killing innocent children all the time. Maybe he’s speaking the truth and he was in the wrong place this evening. That’s not important. When the Delhi boy arrives, he’ll want a list of suspects, they always do. So we’d better find him some.’

Bad Characters

A dust storm blows his daily newspapers and a few loose sheets from open files off their desks, covers his charpai in a thin, persistent layer of grit that Ombir can feel on his skin hours later.

Bhim Sain had quietly taken his shift. ‘Rest is essential to work,’ he had said, quoting one of his favourite gurus, a charlatan who had been drummed out from Punjab for sleeping with his disciples but found a fitful celibacy and a new ashram in Haryana. ‘Without a well-rested body, the mind becomes weaker and more prone to takeover by demons.’

Grateful, Ombir plummets into sleep, but an hour later, he is wide awake. His eyes feel raw and shrivelled, scorched by the heat.

He closes his eyes, takes refuge in pranayama, trying to still his thoughts. And fails. On the in-breath, he sees the branches of the jamun tree. On the out-breath, he sees Chand.

Suspects, their names and faces scrolling on repeat across his tired mind. Teetarpur is a small place. It makes his job much easier, though suspects are sparse in this murder case. Chand and Balle Ram are both well liked in the district, men who avoid quarrels and controversies. When the panchayat meets, they rarely speak, but if work is needed, extra hands to help deepen the common well or fund an extension to the temple in the forest, they’re the first to show up. Balle Ram’s wife Sarita Devi is not known to be quarrelsome either.

The road that runs past their huts carries little traffic. A few trucks on their way to the factories further up perhaps, though most truckers prefer the more convenient main road on the other side. There are occasional visitors to Jolly Singh’s farm, and a small number of devotees who find their way to the temple in the forest. Most of the devout prefer the large, gaudily painted temple in Teetarpur to the hushed shrine.

Narinder is the first person Bhim Sain and he interrogate. A known bad character, a history-sheeter, a man who had narrowly escaped conviction for holding up a goods train thanks to an incompetent prosecution lawyer. He runs a shop on the other side of the forest, quite a distance away from Chand’s hut. The shop sells only a few items—biscuits, hair combs, tooth powder, paan masala, loose tobacco, odds and ends. Ombir and Bhim Sain know that Narinder’s real trade is selling opium and chitta to factory workers and labourers looking for a temporary escape from their problems. They only raid him when he seems too prosperous, when the deliveries of bags of chitta—the synthetic heroin manufactured in Punjab, mixed with dubious ingredients—become too frequent.

Narinder’s name is at the top of Ombir’s list because of something that happened towards the end of March, about two months before this killing. He had received a curt phone call from the manager of Jolly Singh’s farmhouse on his personal mobile number. He smooths out the windblown pages of the two newspapers that he has retrieved and replaced on his desk, the Faridabad Daily Blaze and the Hindi journal Lalten, recalling the incident.

‘This has never happened before,’ the manager had said to him. ‘He banged on our gate for some time, and then lifted up his lungi right in front of the housekeeper and the guards, and relieved himself. Such foul language he was using. Even I didn’t know all the words. What are the police going to do about this? I’ll have to get the gate cleaned with Ganga jal before Jolly-ji returns this weekend.’

When Ombir rode out on his Bullet to investigate, he found Narinder staggering down the road, spewing a stream of curses that he listened to with admiration. The man had a rich and well-flavoured vocabulary. Narinder halted when he saw the Bullet, then regained his courage. He veered into Chand’s fields at a fast clip, emerging with a rusty scythe that hung loosely from his hands. He made a wild swing, almost losing his grip, but managing to hold on to the scythe in the end.

‘Be careful, Chand, he’s not in control of his senses and he’s armed,’ Ombir called when Chand walked up to stand behind Narinder.

Narinder charged at the lantana bushes. Then he reversed direction and ran towards Ombir, switching from curses to war cries.

Chand sighed, returned to his hut and emerged with a blanket. Ombir parked the Bullet and watched with approval as Chand threw the blanket over Narinder, bringing him to the ground. The man struggled like a trapped pig. Ombir looked at the heaving tangle, then kicked at the man’s arms with his heavy boots. Narinder screamed. Ombir whipped the blanket off. Narinder slashed at his face with the scythe, missing his mark.

‘Wrong arm,’ Ombir said to Chand in apology.

Chand grabbed a thorny branch from the weathered fence around his land, and used it expertly to deflect Narinder’s flailing blows. Narinder lost his grip on the scythe, but he continued to fight, weaponless. Ombir circled the pair, waiting for Chand to step back. He landed two quick blows on Narinder’s arm with his lathi.

The pain finally cut through the man’s drug-fuelled haze. He screamed and fought them so hard that they couldn’t get him onto Ombir’s bike. They had to walk him all the way to the station, the two men dragging him along between them, his hands tied with Chand’s rope. He glared at Chand, hatred in his eyes, and said as Ombir Singh formally booked him, ‘I’ll see you, maaderchod, I’ll see you. You won’t sleep in peace or Narinder is not my name.’

‘It’s not,’ Ombir said mildly, locking the door of the only cell in the Teetarpur station house. ‘My colleagues in Punjab know you as Babbu. They’ll be happy to hear you’re doing so well. Men can change their names, but not their nature.’

Narinder had an excellent reason to hold a grudge against Chand, but would he have taken matters this far?

Ombir and Bhim Sain bring Narinder alias Babbu in for an unofficial interrogation. He has an alibi, but a thin one. He was with friends, he says, naming four men. Ombir knows them. Small-time crooks and rowdies, useless louts who weren’t even able to scratch up work with political outfits as hired hoodlums. Narinder is their pusher. They’ll lie for him if necessary.

‘Why so many questions?’ Narinder finally asks.

Bhim Sain says, ‘Only routine work.’

Narinder grins, showing his darkened teeth. ‘It’s about that girl, isn’t it? I told Chand. I warned him, you do wrong by me, the gods will punish you. And they have. Karma is karma. Let him cry for the rest of his days, that bastard, laying his filthy hands on me. Let him weep over his beloved daughter, tasting the air high up in the branches, it’s what he deserves. He brought it on himself.’

Ombir says nothing, watches the man.

‘You think I’m the one who did it? You’re wrong. Many sins are written in my life’s book, but killing children, that’s not for me. I prayed to the gods, give me justice, and they listened. But I didn’t do it.’

Three denials, one after the other, but the man doesn’t betray nervousness. He stands up, says to Ombir, ‘It makes me laugh, you know? Chand looked at me like I was nothing, an insect he’d crushed under his chappals. I wish I’d seen his face when he found his darling daughter. You still doubt me? It’s not my kind of killing. I don’t go in for that, but I’m grateful to the bastard who did it. There’s justice in this world. Everyone gets theirs in the end.’

Ombir Singh believes Narinder. Every man he has known with a taste for violence has had his own quirks, preferences, and killing a child does not fit with this man’s particular appetites. But Narinder has a motive, and he had the opportunity. In his pocket diary, the pages warped by sweat, Ombir writes his name first on the list of prime suspects.

He falls into a doze, jolting awake when a lizard drops from the ceiling onto the desk. Ombir watches the lizard, its tiny translucent feet, the visible innards, and jabs it with the end of a stapler. It twitches and scuttles towards the edge of the desk. He uses the stapler to propel it lightly into the air, where it hangs for a millisecond like a diver about to plunge into the canal, before landing with a plop somewhere near the gutter.

It is a matter of great relief for Ombir and Bhim Sain that Jolly Singh has sent instructions to his staff to cooperate with the investigation. Jolly-ji is the biggest landowner in the area, and Chand’s nearest neighbour, if such an unequal relationship can be considered neighbourly. The manager, Bhadana, has confirmed that Jolly Singh was away in Delhi on work the week of Munia’s death, leaving his farm in the charge of a skeleton staff. All four of the staff have verifiable alibis. The CCTV camera footage shows that they were on the property at the time of the murder.

His second suspect will require careful handling. Dharam Bir, head foreman at the Sangam Soap and Heavenly Incense Factory, built on the lines of a prize bull—massive shoulders, lowered head—and as quick to anger as one of those creatures.

This factory’s owners, the Saluja family, are the biggest donors to every local politician. Saluja runs several companies, and is rumoured to be in partnership with Jolly Singh himself, something to do with a new township. Ombir keeps the interview short, casual, takes care not to offend Dharam Bir with direct questions. But he has many questions, asked and unasked.

Some months ago, in spring, the daughter of two daily wagers had disappeared. The twelve-year-old was missing for a night. When the parents came to the thana, the mother could barely speak, choked by her fears. The father could not keep the tears from welling up. They told Ombir that they had searched the fields and gone down to the canal, and had finally received permission from the guard at the Sangam Soap and Heavenly Incense Factory, who said that they could return in the evening and look around the premises so long as the owners didn’t find out. ‘She’s mute,’ the father explained. ‘She would not be able to scream for help.’ Hesitantly, he asked Ombir whether the policeman would search on their behalf. They were nervous about getting into trouble with the owners, despite the guard’s offhand permission.

The girl was discovered in a musty shed, dark and cobwebbed, in the empty lot near the factory. She wore only a pair of thin printed cotton panties, and when Ombir and Bhim Sain entered the room, she clutched her only other garment, a flimsy chiffon dupatta, to herself. The rest of her school uniform, her kurta and pajamas, was missing. Her breasts had not yet developed. She was a skinny child. Her ribs stood out.

Ombir could see no visible sign of injury, and after she was returned to her parents, the mother swore that the girl had not been raped. She used the word ‘damaged’. Afterwards, Ombir searched the shed thoroughly. The only item of note he found was a crumpled list of machinery, handwritten on a torn page. He thought he could make out a signature in Hindi, a man’s name in confident black ink. Dharam, just the one word.