0,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Existence is about survival.

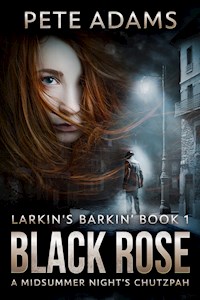

A continually bullied runt of a youngster, Chas Larkin discovers his chutzpah and decides to take on the London gangs.

In the sleazy and violent East End of 1966 London, he is unwittingly assisted by Scotland Yard and MI5, who use the boy to delay an IRA campaign in the city. Together with the mysterious DCI Casey, an enigma amongst the bomb-damaged slums, they stir the pot of fermenting disquiet.

But can Chas achieve his midsummer night's dream of total revenge?

Black Rose is a story of matriarchal might, of superstition, of a lucky charm tainted with malevolent juju, and of a young man's smoldering anger and thirst for retribution.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

BLACK ROSE

LARKIN’S BARKIN’ BOOK 1

PETE ADAMS

CONTENTS

Books by Pete Adams:

Preface

Acknowledgement and Dedication

Foreword

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Roisin Dubh

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chas finds his Chutzpah

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Next in the Series

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2021 Pete Adams

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2021 by Next Chapter

Published 2021 by Next Chapter

Edited by Fading Street Services

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

"The lunatic, the lover and the poet, are of imagination all compact"

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE - A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM

BOOKS BY PETE ADAMS:

The Kind Hearts and Martinets Series: (Part one of the 14 book Hegemon Chronicles series)

Book 1 Cause and Effect – Vice plagues the City

Book 2 Irony in the Soul – Nobody Listens like the Dying

Book 3 A Barrow Boy’s Cadenza – In Dead Flat Major

Book 4 Ghost and Ragman Roll – Spectre or Spook

Book 5 Merde and Mandarins – Divine Breath

---------

The DaDa Detective Agency - Sequel to Kind Hearts and Martinets: (Parallel series to form a part of the 14 book Hegemon Chronicles series):

Book 1 Road Kill – The Duchess of Frisian Tun

Book 2 Rite Judgement – Heads roll, Corpses Dance

---------

The Larkin’s Barkin’ series – East End of London, gangster family, saga: (The first two novels form a back story to the 14 book Hegemon Chronicles series):

Book 1 Black Rose – A Midsummer Night’s Chutzpah – 1966

Book 2 A Deadly Queen – 4 Wars

---------

The Rhubarb Papers: A spin off Sequel to Kind Hearts and Martinets (The first two novels form a part of the 14 book Hegemon Chronicles series):

Book 1 Dead No More – Rhubarb in the Mammon

Book 2 A Misanthrope’s Toll

PREFACE

A few years before I wrote the first draft of this book, summer 2015, I attended PortsmouthPoise, an Arts gathering organised by Ed Woodruffe, Trudy Barber and Elaine Hamilton. Each attendee was asked to select an item from various objects in a glazed cabinet and instantly compose a five-minute short story to be read later that evening. I chose a burned crumpet, a bite taken from it. It had the following note attached:

"This homemade crumpet was one of a batch baked in the kitchen of the 'Cat and Fiddle' pub in Stepney, in London's East End, on June 8th 1924. Bessie O'Riordan, who ran the pub, made crumpets every year on her son Jack's birthday, because they were his favourite food. Unfortunately, Jack had been missing, believed killed in action since 1917, but she continued to make them every year in his memory.

Regulars were given buttered crumpets to eat with their pints every June 8th, but in 1924, she burned the first batch. Bessie was about to throw them out when the owner's grandfather entered the pub and announced the birth of a son, Sam, to Bessie's surviving son. He asked her for one of the burnt crumpets to keep as a token to remember Jack, his grandson and commemorate the birth of Sam - the crumpet is now well beyond its sell by date and should not be digested."

I composed a short story and read it out; Chas Larkin was born. Returning home and, well into the night, I wrote the opening chapters of Larkin's Barkin'. I archived these chapters and my notes in order to complete the Kind Hearts and Martinets series. Larkin's Barkin' was intended to be a one-off crime thriller, but upon returning to the work in progress and, as the story developed and the characters grew strong in my mind, the seeds of a series was sown. Book two: A Deadly Queen – 4 wars and Book 3 A Holy Death - Dead, Dying or Gorgeous, will follow.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT AND DEDICATION

The crumpet script was written by Colin Merrin, an East End lad himself and now, an exceptional artist painting in Portsmouth. Colin has told me since that the idea was inspired by an East End of London myth about a Stepney young man who did not return from WW1, and his mum, who ran a pub, made buns (not crumpets) on his birthday every year until she died. True or not, this myth was a great catalyst for this my ninth book, and I dedicate it to Colin Merrin.

The painting is of his Grandmother, Great Grandmother, and Uncle - the coincidence of East End matriarchs, with a boy between, was too much to ignore, even if the narrative bears no resemblance.

1916 by Colin Merrin

FOREWORD

In this story I introduce a concept of The Black Rose as a mythical Irish character. I ask forgiveness from the Irish people who I have taken to my heart after meeting my long-term partner, June Merrigan; Siiobhain ni Mhuireaghain, her Irish name. When we met, so many years ago, June had a jet black cat she called Rosie, named for the benefit of the English. The cat's Irish name was Roisin Dubh, Black Rose.

Wikipedia describes a Black Rose: "The symbolism in many works of fiction usually contrives feelings of mystery, danger, or some sort of darker emotion, like sorrow and obsessive love."

Crumpets - an Anglo-Saxon creation that originally were thought to be hard pancakes cooked on a griddle, rather than the spongy confection of today and very popular in Britain.

Chutzpah - Unusual and shocking behaviour, involving taking risks, but not feeling guilty; audacity, boldness...

It is not certain that everything is uncertain

BLAISE PASCALL

PROLOGUE

THE CRUMPET

Misery rife, fear endemic, because of a dodgy crumpet. Burned, one bite taken, preserved, and dating back to just after the First World War. The whiff of undertaker’s formaldehyde would be sickening if ever you took it from the glass display case, sat on the back bar where it had pride of place. However, that crumpet stood as a marker of an uneasy peace in the East End of London. Lost and found, lost and found again, amongst the bodies of retribution and counterattack, always recovered, signal in the strength of one family, the Saints.

The family factions, long established in the East End of London, were the Saints and the Larkins. The Saints, the larger, more established, villainous family, held in check, one could say, by the precocious, lunatic may be more appropriate, Larkin family, who knew no fear when all around knew they should. And so, the lines of friction between the two families became white hot and sparked whenever the crumpet went missing.

And the O’Neill’s? Not much was known of this mysterious Irish immigrant family, said to hail from County Clare, West of Ireland and, seemingly uninterested in owning a pub and disinterested territorially. Yet nevertheless, they asserted an untouchable presence.

Regardless of the ephemeral O’Neill’s, the familial territorial headquarters was always the pubs, Dad’s and Arrie’s, both colloquial names, long established in local culture and street mythology.

Dad’swas located in Stepney, deep in the heart of the East End of London and, Arrie’s, in what can only be described as an uncomfortable distance away, next door. The two mutually dependent, though independent, pubs, were competitors and, the proprietary families as adversaries, extraordinarily, had a shared support of each other. You could not raze one pub to the ground without the other suffering a similar fate. Or so it was thought.

It was from here in semi-detached disquietude that the Saints controlled the Docks, their ground, and the Larkins, the gambling houses, brothels, and most other satellite industries, servicing mainly the docks, the dockers and the sailors. So it was that the families needed each other in another twist of fate. Which was the most fertile business depended on your point of view. Either way, the businesses were bombproof in that the docks were untouchable and, you could maybe destroy one or two of the Larkin properties, but not all, and then you would have a war so brutal and what would be the point, after all, the Saints and Larkins were neighbours, literally.

The crumpet was the symbol of a capricious peace. Every now and then the confection disappearing and later returned, the Saints temporarily vulnerable.

To understand the ground, you need to comprehend the history of the two families, though it would be more appropriate to say that the umbilical reason for the current violent turbulence of street politics, would be just that, and, in that maelstrom of tinder dry factional streets, was born and nurtured, in a non-maternal sense, an unlikely nemesis. And so it was, from this most unusual and unexpected direction, the life-sustaining chord of palpitant peace, was cut. The bête noire scourge, emancipated. Although, as it transpired, the adversary was totally unaware he was even free or, was a preceptor of ruination, being insensitive to his latent genetic chutzpah. This was a man destined to be Public Enemy number one. To be pursued by the Metropolitan Police, Special Branch, MI5 and, closer to home, The Saints and, to a lesser extent, The Larkins. And in all of this, there was The Black Rose.

* * *

The Saints.

Bessie Saint had been the fierce landlady of the Dog and Duck Pub in Stepney, the East End of London. The locals, in the vernacular, called the pub a Rubbadub and, colloquially, Dad’s, as in the initials of Dog and Duck, but mainly in memory of Dad, old Mickey Saint, Bessie's beloved and sadly departed husband. He was said to have copped it at Passchendaele in the Great War, November 1917. Dad Saint, Dad's owner, was dead. It was, however, business as usual, as in reality Bessie had run the pub and just about everything, as was the East End matriarchal way. Old Mickey thought he ran the family firm, but he didn’t. The brains of the outfit was Bessie and she had taken on the role from Mickey’s Mum and, before her, Nan Saint. Bessie was highly suited for the job and had been selected for Mickey. Extraordinarily, this arranged marriage produced a love match, at least this is what Bessie told everyone, and who would be brave enough to contradict her? Certainly not Mickey, who was not averse to a bit of kneecapping and murder, but only if Bessie said so.

When news reached Dad’s of Mickey’s demise, Bessie had been conspicuously devastated. Under her guidance, he had run a tight ship in the principal family businesses: control of the Docks; extortion; violence; robbery; with the occasional dispatching of the unwanted, those who had transgressed the unwritten law, Bessie’s Law. And what was that law? Nobody knew, she was not one to write things down, administration not being her bent, though she was firmly on the opposite side of law and order in just about everything else. The Saints were gangsters and had a serious rep.

Since the demise of her husband, Bessie, overtly ran the Saints gang with an iron fist and, she ran a tight ship in Dad’s. When her eldest son, Mickey junior, who would have been the natural de facto successor, was, towards the end of the Great Conflict, declared missing in action, a military euphemism for dead, Bessie was truly devastated. She didn’t give a toss about her husband, but she missed her Mickey Junior sorely. She set a tradition to commemorate her beloved son Mickey’s birthday, and, on the 8th June every year, she would bake his favourite crumpets. These would be shared in the pub where everybody would salute Mickey Saint, eat heartily of the tasteless and often burned, small and round, perforated, bread-like confection, either dripping with melted butter and a green parsley sauce liquor or topped with jellied eels. At regular intervals, as if eating the vile crumpets was not bad enough, you were expected to raise your pint glass in a toast and shout, “Mickey Saint - the little devil”, because Mickey had been a dirty, rotten scoundrel. He had been evil through to his core and ever since he could toddle, Mickey Saint had scared the living daylights out of everybody he met. This was the Saints; a villainous family and they learned their trade early on in life.

And so it was, on the 8th June 1924, Bessie had burned a large batch of crumpets, as had become the tradition and the crowded pub was effused with the charcoal aroma of the nauseating delice-confection. The clientele, scared for their lives if they didn’t attend this auspicious occasion on the East End of London calendar, were all in attendance, waiting to share in the ceremonial crumpets, when the door opened and in walked Mickey Junior, as large as life and twice as dangerous. Nobody knew where he’d been, what he had been doing since 1918, for it had been just a few weeks before the end of the war when he had gone missing. People later suggested stories, all in the realms of fantasy, but one thing was sure, Mickey, the little devil, was back, rolling in filthy lucre and ready to resume control of his Manor, as was his right, because Bessie deemed it so.

That auspicious evening, Bessie declared free drinks, and the party, which was to last well into a third day, got under way to the smell of more burning crumpets, singing, dancing, and the occasional bottle on someone’s head (that unwritten law again). At one point, Bessie panicked and retrieved from the bin the blackened crumpet she had been eating when her son had miraculously appeared, she’d taken one bite out of it. This would be a keepsake, a charm and she set it on the back bar shelf, announcing, “This is one lucky fucking crumpet”, and thus it was given its place in Dad’s. And, over time, the revolting crumpet became imbued with powers beyond its indelicate taste as Bessie further announced, it was the Saint Crumpet. It was never to be touched by anyone other than a Saint, on pain of, well, loads of pain and, if you were lucky, death. Another unwritten law that everyone acknowledged need not be written down as they, in their turn, would pass the knowledge onto their children and their children’s children, in the way of all good diabolical East End myths. But, on that day of great joy for Bessie, she doled out the Saint largesse in the name of charcoal crumpets as if they were a true East End delicacy, topped with jellied eels or the green parsley liquor, to cover up the black surface and, people ate them, mumming and aaahing in feigned delight, as if their lives depended upon it, which they did.

The party had been well into its second day when the door of the Public bar crashed open (can nobody open a door quietly?) and Ancient Mickey, the grandfather, entered and announced the birth of Sam, Bessie’s first grandchild, whom Bessie immediately rechristened Mickey. This had truly been an auspicious time for the Saints and Bessie put this turn of great fortune down to the burned crumpet, not so much the jellied eels or the green sauce and, drawing everyone’s attention to her, she pointed to the crumpet on the back bar shelf, the bite marks of Bessie's false teeth evident, and she announced to all that this crumpet would be the symbol of the future prosperity and immunity of the Saint family.

The customers in the crowded pub parodied great hurrahs whilst under their breath muttered in trembling fear, “Just what they needed, a bullet-proof Saint family dynasty”. Which is what they got. The success believed by everybody, but no more than the Saint ascendency, to be attributed to the burned crumpet.

And even to this day the preserved crumpet sat on the back bar of Dad's. It had pride of place in the Dog and Duck pub.

When I say, “until this day”, I should have said, up until this day. For this day, this ominous and dark clouded, foreboding day, someone had entered Dad’s in the dead of night and purloined the Saint family’s lucky charm and replaced it with a crumpet, similar in appearance, but one imbued with malevolent juju. You could say that on this portentous day, the Saints were doomed.

But what of the Larkins?

* * *

The Larkins.

As in the tradition of all westerns, or in this case EastEnderns, there was a rival to the established villainous family. That family, the Larkins, equally villainous some would argue and live to regret it, owned the Bottle and Glass pub, known to those who favoured a walk on the wild side, or even those who walked the tightrope between Dad’s and the Bottle and Glass, called this pub, the thorn in the side of the Saints, Bum’s; bottle and glass being cockney rhyming slang for arse and this over time, became Arrie’s, as in Aristotle – bottle (and glass) – get it? Some would say you needed a language degree to live and, survive, in the East End of London, but truthfully you would be better off with an invisibility cloak, or just get the hell out, and some did.

Arrie’swas a seedy pub, ironically, in the arse end of Stepney and, if you stood back and screwed up your eyes, the Victorian bottle green and brown glazed tiles, acid etched glass, gave the pub an air of Hansel and Gretel classic beauty. However, if you were of the mind to partake of a pint or two within Arries and wore a tin hat and pads, you might discover it was not just a pub with visual character, you would learn it was patronised by characters, all of whom would not pass stage one of any sainthood test, not being in the Saint clan for instance, test one, but would pass with flying colours any test you threw at them for knavery.

* * *

Nonetheless, and despite the rivalry, Arrie’s stood next door to Dad’sand both pubs had a different visual character, if not dissimilar characterful patrons, all villains, in one way or another.

Of course, villainy came in very different forms and, when you grew up in this area, you either set your mind to getting out as soon as possible or, if you chose to stay and get a sensible job, you mainly stayed indoors after dark. The alternative was you commenced your apprenticeship in various categories of turpitude, eventually specialising in some form or other. Violence was always popular, and could be combined with aggravated burglary, or intimidation and such like. Further up the hierarchy were people considered skilled, like safe crackers, sappers, known as Petermen, good at fusing and defusing bombs and, there were specialists in alarms, and so on. There were and always had been, informers, or grasses as they were known; grasshopper, copper shopper, to shop villains to the filth, police, or so the story goes and, these informants came in two categories of stool pigeon. Your ordinary weaselly double-crosser, making a living for what often turned out to be a short life, sourcing naughty information for often a pittance of cash, in exchange for feeding the police with underground intelligence. All grasses aspired to becoming a Super Grass. It was like a career ladder within the telling on people cognoscenti, but on the more perilously precarious edge. The earnings were greater, commensurate with the heightened danger, but at the end of a career as a super grass, if you survived to say, forty-five, you could be given a lot of money and witness protection. You could maybe be shacked up in a luxurious villa, in a part of the world with a sunny clime. Least, this was the aspiration, but only a few made it to those dizzy heights, though the police encouraged these vocational ambitions.

And the numbers were made up by the East End plebs. The sycophants, living the life they had been born to, hanging on, often for dear life, suckered into a spiral of associated crime or denial, both intellectually and if the police questioned you. Even if the consequent tentative alliance and radiant admiration with known criminals, of the various category, gave you a certain cachet, hangers-on rarely got beyond a nodding acquaintance with the upper echelons of evil-doers and, hardly ever with the big boys. The masses were there to make up numbers and to stand by and laugh at jokes when made by those who would sever a limb or two without blinking an eye, if you didn’t convulse in excessive jollity at often very poor jokes. Why is it gangsters think themselves whimsically entertaining?

Such was life in the oft eulogised East End of London. Not fun. Not a big loving family, but a life on the edge, and tolerated only by developing a rare sense of humour, bordering on denial. Everyone liked a tin bath, (laugh).

And so, the myths were handed down in both the Saint and the Larkin family. Some did get out. Charlie Larkin’s granddad had escaped, as he put it, having found himself a beautiful woman, Alice, who absolutely insisted she would not marry him or bring up a family if it meant continuing to live in the dog eat crumpet world of villainy. She was escaping also his family pub and reputation and, Charlie Larkin (the granddad) was her ticket out of the East End of London. A bonus for Alice was that he was a kind and generous man who loved the bones of his Alice.

Charlie’s granddad had moved to Portsmouth, a sort of home from home for EastEnders, only with a bastardised country accent and they took over a pub and renamed it the Bottle and Glass, after the family hostelry back in London, not that it existed anymore. In the Blitz, the Luftwaffe had done the Saints a service by bombing Arrie’sand leaving Dad’s remarkably unscathed, even the crumpet, and that was also seen as auspicious.

The Larkins steadfastly resisted selling the freehold of the bomb site and, eventually rebuilt it in a style that overshadowed Dad’s both physically, architecturally, and emotionally – it was a modern design with all mod cons, hot and cold running blood.

And that was where the good sense ended, for Alice's eldest son, Charlie, who on visits to the family in London, trained hard to be a scumbag. Eventually Charlie returned to his so-called roots after his mum and dad tragically died.

Charlie, blind to all good sense, not least going back to the villainous way of life, married Betsy, a brazen Dockland tart. They had six kids and lived in a cosy East End hovel. The youngest child was called Chas, a diminutive form of Charlie, and he was a runt of a boy. Chas would ask why they did not go to Portsmouth and live with that family? He was, of course, cuffed for his impudence, the seaside home for Chas a distant fantasy. He was destined to remain in the East End of London, a place he hated, for alas, he did not have the chutzpah to leave and, probably never would. He was just like his Dad, so it was said, a famed cream puff.

1

THE YEAR, 1966

The Street

‘Allo Chas,’ drawn out and minacious. Mickey Saint junior at fourteen was not of big build, but he was menacing. It was in his genetic code. Even at this young age those fearsome bullying genes were fully developed into a playground gangster: Mickey Saint junior’s manor.

Chas Larkin was frozen to the spot. Even though it was a warm summer day and the sweat drained down his petrified spine, he was chilled to the marrow. In his daydreams he imagined himself in another part of the world. Somewhere safe at least. He didn’t ask for much, just to be safe. It was how he survived. He regressed into his dreams of a safe haven and, when he couldn’t do that, he did things he thought might be lucky, like avoiding the cracks in the pavement.

Whenever he managed to get in some words to his self-absorbed mum, asking could they move, maybe to the countryside, she laughed at him. "We're EastEnders", and, “this is where we live”, she would say, waving her arms about her as if the still bombed out East End of London was a glorious place to be and Chas should be grateful. He wasn’t. The place was the pits and he hated it. It scared him. “But I don’t like it mum”, a statement that would be met with further derisive laughter and his mum would flounce, telling her friends, in his presence, mimicking a whining childlike voice “But I don’t like it mum”, to the great amusement of her audience, and deep embarrassment of Chas. She would flick his ear, or clump his head and, if she was drunk as a skunk, she would give Chas a right-hander that could knock him from Sunday to Monday.

‘Cat got yer tongue?’ Mickey Saint assayed as he strutted around the paralysed Chas, grasping his school satchel tight to his chest. It didn’t hold anything valuable, but he had learned it could shield a blow or two. Mickey’s gang leaned back, casually, hands in the pockets of their short shorts and laughed to the sky as Mickey prodded and taunted the trembling scaredy-cat, Chas Larkin.

Chas had no answer. He’d quite like a cat, but truthfully would prefer a dog. A dog could protect him. “Some chance”, his mum had said, she had enough on her plate with six kids, of which Chas was the youngest and the burdensome runt of the litter, least this is what everyone told him, so he supposed he was. Chas was not sure what runt meant, but knew it wasn’t good, because he didn’t know of anything good. Nothing was good in his life.

Mickey flicked Chas’s nose with thumb and forefinger, looking to his gang to bathe in accustomed glory as Chas rocked backwards in fear, which move gave Mickey the distance to wind up a haymaker. Chas knew it was coming, it always did, he wished he could run, to seek temporary respite in one of his many hideouts he had acquired as a means of self-preservation, but that wasn’t going to happen. You try running with eyes that looked in different directions, where do you go? And he wouldn’t get far with a club foot. His left foot twisted, not seriously, but enough that the sole could not be placed fully flat on the ground. Eventually he had been given a big shoe that had the sole and heel shaped and raised up. Chas was not sure what was worse, the sight of the club boot that so clearly did not match the shoe on his other foot, or his inability to walk like other kids, although he practiced, every day, desperate for some semblance of normality, which to Chas was the ability to blend into a safe background. Of course, it was the boot that everyone spotted first, the rest just followed as a natural consequence. It was Chas’s lot and, he had just to get on with it was the sage advice from a distracted and uncaring mother. No maternal safe haven there.

Mickey’s blow landed square on the runt’s jaw. Chas was laid flat and had just enough time to curl into the foetal position before Mickey and each of his sick sycophants, popped in a kick or two as they passed by on their way to school.

Chas was going the other way; he had a doctor’s appointment. He often did. He was what his mum called, “a sickly wimp of a runt”, going on to say, in an amusing manner, that “her Charlie should ‘ave drowned him in the Thames at birth, it's what they would’ve done in the old days”. Then she would tell all how she was a martyr to the kid, like she was the victim, it was she who had the task of raising a child so demanding, and she’d clip Chas around the ear again for being a burden to her. Her solution to everything, if she wasn’t flat on her back pissed, or shagging her way around the East India docks. Regularly, she would drag him off to the doctor's surgery as though he were a trophy, enabling her to suck in sympathy and caring endearments like a sponge. For her, not him; nobody cared about him.

‘Get up ‘orf the fucking floor, them cloves were clean on a week ago. What will the doc fink?’

Chas raised his bruised, emaciated, and deformed, elongated frame, to face his mum. If his self-esteem would allow it, and were he to stand upright, Chas considered he would be tall, but his body, like his ego, was seriously dented and emotionally curved inward, as if to form a hunchback's defensive shell. He leaned into his mother as she tugged his ear and pulled him towards the doctor’s surgery, his tiny pleas choked off in a cloud of cheap, brassy perfume and the acrid aroma of lacquer from her beehive hair. He knew better than to tell her he hurt, his mother didn’t care, and he often wondered why she so regularly took him to the doctor.

His mum was a looker, he had to agree with that. She dressed stylishly and often he wondered how come she had money for such lovely clothes, yet his own un-glad rags came from the Salvation Army? Another question he would never ask, as he clumped along following his mum who had not released his ear, and he buried his tears, buried his pain, and stifled his anger. Chas Larkin knew no other way. He repressed his so called fourteen years, so that inside he was still a small and vulnerable boy. He had no idea how old he was, or even his birthday and, what would be the point.

-------

The Doctor

‘Allo Chas.’

Chas liked Thelma, the doctor’s receptionist. She was a warm buxom lady with mountainous bosoms that Chas loved to sink into when he received her motherly embrace, before showing them into the consulting room. Always sending him off with a fond ruffle of his hair. It was the closest he got to any stirrings that might encourage the growth of his inhibited adolescence. Chas had regular check-ups at the Docs. His mother made an inordinate fuss about all of Chas’s distorted limbs, organs, and bits and pieces. It seemed to him to be the only time she cared and, oh how she and the doc laughed at his stunted growth, his inability to make that step into manhood.

‘Lazy eye.’

‘Lazy eye?’

'Lazy eye.’

‘Lazy...?’

‘Lazy eye,’ the doctor reaffirmed, a brief nod that permitted him a cursory squint up Betsy Larkin’s skirt: stocking tops. There was nothing lazy about his eye.

‘Lazy eye?’ Chas mumbled, trying to offer some substance to his still high-pitched and squeaky voice. Betsy clipped her son’s ear, the Doc seeming to approve the chastisement with a glancing blow himself whilst distracted by Betsy’s physical charms. Chas said nothing, not even ouch. He was used to it, though his temper, which bubbled and grew within him, permitted a rebellious clump of his club foot onto the polished floorboards of the surgery. He felt a little better. He had always had a squint, so why now? Why had the doctor at last thought his eye needed attention?

‘What shall we do?’ Chas’s mum asked insincerely. She found the Doctor inordinately attractive and he had such a lovely touch.

Doctor Byrne sashayed to the front of his desk like a lounge lizard, perched on the corner, and leaned over, facilitating an improved inspection of the creamy white thighs of Mrs Larkin and, whilst remaining focused on the black nylon tops, he scrabbled around Chas’s face to remove the National Health, circular, wire framedglasses, scratching Chas’s nose in the process. A trickle of blood trailed, to be ignored. Chas said nothing, he was used to being clumped, scratched, and beaten up generally.

Betsy slapped her son again. It was her default action, although her response seemed to have a reasonable motive, at least in her mind and, taking the spectacles from the doctor, she admonished her son. ‘Look at the state of these bins, yer filfy...’ and she demonstrably lifted the hem of her flowery cotton dress and, leaning down, adjacent to the doctor’s fly region, she exaggerated exhaling a throaty breath onto the lenses and, with excessive and suggestive vigour, she cleaned them. The doctor was thus afforded a clearer view of Madam Larkin’s under garments, which was of course the intention and the resultant mounding in the doctor’s trousers was noticeable. Not to Chas though, he was as blind as a bat without his glasses, compounded with a lazy eye he had just learned, but he knew what was happening. It had happened before and his disabilities he thought to himself, were more often than not used as an excuse for his mother to visit the doctor. Still, it got him off school for a short while. He hated school. It was torture, even though he was academically gifted. The teacher had said this, but his mother had not listened, after all, in the East End what use were sums and writing, and clearly Chas did not have the where-wiv-all to follow his brothers into the family business. He was viewed as a waste of space.

Doctor Byrne, hunched over, raised himself from his perch. Chas heard a ripping of sticky Elastoplast and, still distracted by the intimate lady view, now fully exposed, Doctor Byrne roughly taped up the lens that serviced Chas’s good eye and thrust the glasses back to the intimidated boy, dismissively telling him to wait outside.

Betsy glanced at Chas and told him to fuck off to school.

Chas fumbled the floor to pick up his glasses that had received no purchase on his face as the distracted doctor had attempted to replace them. Having found them and put them on, he found that now everything was a blur. His one good eye, though often facing the wrong way, was blinded, to teach the other one a lesson. He stood and with outstretched hands, he fumbled his way to the door and into the waiting room. The door closed to a squeal of feminine exquisite pleasure, and then a thud.

Chas stood still for a moment getting his blurred bearings, fighting the desire to cry. He felt the warm embrace of the comfortably plump receptionist who tugged Chas into her ample bosoms. This was what Chas looked forward to on every visit to the Docs. It was his only comfort. Now he cried. He was for the moment, safe, and Thelma removed the plastered glasses and dabbed his eyes with a perfume drenched handkerchief, caressed his head and kissed his damp cheeks. ‘Fucking the Doc, is she?’ Chas nodded, squashing himself into her body and she hugged him tight as she walked him to the door. ‘Lazy eye?’ she asked, and Chas nodded again, knowing the embrace and the comfort would end as the indistinct image of the door neared. Just the last kiss to go and he will have to face school.

Thelma kissed Chas. He didn’t know, but there was a strawberry pair of lips printed on his cheek. He wouldn't care anyway because he relished the warmth, the milk of maternal nurturing and Thelma's kindness. He’d been standing on one leg having learned this was lucky and, so he thanked the Gods as he cherished the last vestiges of the luck and, the receptionist’s cuddle, the final wisps of her womanly scent. He loved it, but he had to get to school.

* * *

School

Although the streets were familiar, Chas’s drastically reduced vision made his walk to school difficult, treacherous even. Busy roads had to be negotiated. Shouts and car horns filled his extrasensory ears, serving him well, but much occluded by the pulsing thump of his heart.

Eventually the familiar smell of dog shit and disinfectant told him he’d reached the school entrance, not the playground gates, they would be locked by now to keep the kids from escaping. It was a short flight of stone steps to the double doors of the imposing, if you could see, Victorian portico. He stepped inside, knowing what would be waiting for him.

‘Larkin, you’re late,’ the stern voice of the school secretary echoed in the voluminous gothic vestibule. Chas needed a wee and was not sure he could hold on as the dragon neared. Sensing the fire of her breath, he was able to anticipate the swing of the slap, so it took some of the momentum and sting out.

‘Me mum sent a note. I’ve been...’

Slap, he didn’t sense that one. ‘We got no note from that strumpet of a mother of yours.’

Chas waited, no slap, no more berating.

‘Mrs Coggan, perhaps I can take Chas to his class?’

Oh, the wondrous breath of respite, the elation of escape. ‘Miss, er, Doyle? Is that you, I cannot see very well, er.’

Slap.

‘Mrs Coggan, enough of that now.’

Chas sensed the secretary withdraw from the vestibule arena of conflict, retreating into her lair, and he leaned into the gentle caress of Miss Doyle as she stroked his reddened cheek, a slight abrasion from her handkerchief as she erased the imprint of Thelma’s voluptuous lips. ‘Come along Chas, let me get you to your class.’

‘Thank you, miss, but I need a wee.’ Chas imagined the caring smile of Miss Doyle rather than witnessed it.

‘Can you find your way to the loo? Lazy eye, is it?’

‘Yes, miss, lazy eye,’ and Miss Doyle spiralled away, just a gentle smoothing of Chas’s cheek that he pressed into, to savour, until the dragon breathed fire through the glazed portal of her secretarial den, insisting he get a move on, and to ask his mum to contact the school. Well, he’d tell her, but fat chance she would comply.

Chas felt his way into the corridor and, assisted by the smell of poorly aimed urine and, inadequate disinfectant, he found the door, entered, and panicked. The distinctive aroma that was the Boy's toiletwas compounded with the smell of cigarette smoke. This could only be Mickey Saint and his gang. Somehow teachers allowed him and his brethren to get away with murder, perhaps because they had murderous back-up outside the school. The teachers didn’t care, just longing for the day when he and his entourage would graduate to the streets.

Mickey Junior whooped with glee when he saw Chas Larkin enter the lavatories. Chas considered legging it, but he couldn’t see and his second beating up of the morning would probably be less debilitating than an accident running the corridor, maybe even a tumble down the stairs. So, he braced himself, but was unable to prevent whizzing in his pants, the resultant streaming down his legs unavoidable and visible. This act of incontinence was greeted by the Saints with convulsive derision and cavorting depraved merry japes, regaling Chas with names, all toilet humour based, the hoodlums not having an expansive knowledge of the English dictionary, and this served only to scare Chas more and to turn his bowels to water.

A soft Irish accent, a girlish lilt and, a gentle touch, ushered Chas back into the corridor. ‘Roisin?’ (Pronounced Ro-sheen) he enquired. Chas was the only person who called Roisin by her baptised Irish name, most called her Rosie, or Ginger Nut, and Chas’s determination to name her correctly meant he was a firm favourite of this vivacious and head-strong girl from an Irish immigrant family. He respected this girl. She had withstood all the banter about her unruly mop of ginger curls, freckles, and her lanky ungainliness, generally with a swift right hander, followed up with a threat of a belt from her Dah, if any of the parents felt like taking issue with her, and the threat of the O’Neill family had sway.

The O’Neills, although new to England and this East End neighbourhood, were establishing a firm don’t touch reputation, Dah O’Neil reportedly earning substantial money as a successful bare-knuckle fighter back in the Emerald Isle, and along with a host of equally capable and protective brothers, Roisin had confidence aplenty. Chas admired it, admired her. Not much else was known of the O’Neills and people presumed that eventually they would be dealt with by either the Saints or the Larkins.

In the meantime, their reputation preceded any O'Neill. ‘Hey, Rosie, we were just ‘aving a larf like,’ Chas heard a cowering Mickey say, his disciple backup having faded into the toilet cubicles. Nobody messed with this red-headed lunatic who carried her fifteen years, maybe older, status to great effect.

‘It’s Roisin, Mickey, and I thought I told you to leave Chas Larkin alone, so?’

‘It’s okay, Roisin,’ Chas mumbled, extending the end of her name out of respect, the dampness of his trousers and his wet legs causing him to feel a chill from the draughty corridor.

* * *

The Police

Miss Doyle, sensing she ought to check on the toilets, found Chas shivering and hunched in a crouch in the corridor. She embraced the wreck of a child and not letting go of her hug, she took him off to the gymnasium. After cleaning him, she gave him some lost property gym shorts, saying she would wash his school ones and dry them in time for when he went home. Chas was so grateful he cried more, welcomed the further tug into the waist of the teacher’s skirts and lingered as she calmed and soothed him, but eventually, ‘Okay, we've been some time. So, let's get you to your classroom.’