Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: АСТ

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Легко читаем по-английски

- Sprache: Englisch

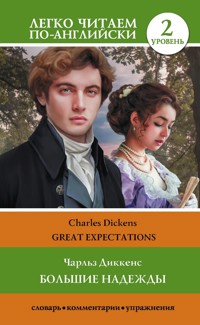

Чарльз Диккенс – английский классик, признанный во всем мире. Его произведения переведены на многие языки, постоянно переиздаются и часто экранизируются. Роман «Большие надежды» - одно из последних произведений автора. Он повествует о жизни молодого человека имени Филипп Пиррип, которого в детстве прозвали Пипом. Будучи еще простым мальчишкой он влюбляется в прекрасную Эстеллу, но она лишь играет с ним. Но внезапно некто, пожелавший остаться неизвестным, жертвует большую сумму на содержание Пипа. Сможет ли он стать настоящим джентельменом и завоевать сердце возлюбленной? А главное, не будут ли разрушены его большие надежды, когда он узнает, кто является его благодетелем? Произведение адаптировано для уровня знания английского A2. Для удобства читателя текст сопровождается комментариями и словарем.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 241

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Чарльз Диккенс Большие надежды. Уровень 2 / Great Expectations

© С. А. Матвеев, адаптация текста, коммент., упр. и словарь, 2023

© ООО «Издательство АСТ», 2023

Great Expectations

Chapter 1

My father’s family name was Pirrip, and my Christian name was Philip. So, I called myself Pip.

My sister, Mrs. Joe Gargery, married the blacksmith. I never saw my father or my mother.

That day I was at the churchyard. I was very sad and began to cry.

“Keep still[1], you little devil!” cried a terrible voice. A man stood up among the graves, “or I’ll cut your throat!”

A fearful man with a great chain on his legs. A man with no hat, and with broken shoes. He had an old rag tied round his head.

“Oh! Don’t cut my throat, sir,” I pleaded in terror. “Pray don’t do it, sir.”

“Tell me your name!” said the man. “Quick!”

“Pip. Pip, sir.”

“Show me where you live!” said the man.

I pointed to our village, a mile or more from the church. The man turned me upside down[2], and emptied my pockets. He found a piece of bread.

“You young dog,” said the man, “where’s your mother?”

“There, sir!” said I. “She lies there.”

“Oh!” said he. “And is your father with your mother?”

“Yes, sir,” said I.

“Ha!” he muttered then. “Who do you live with?[3]”

“My sister, sir – Mrs. Joe Gargery – wife of Joe Gargery, the blacksmith, sir.”

“Blacksmith?” said he.

Then he looked down at his leg.

“Do you know what a file is?”

“Yes, sir.”

“So bring me a file and some food. Or I’ll eat your heart and liver.”

I was dreadfully frightened. He continued:

“Listen. Bring me, tomorrow morning, the file and the food. You will do it, and you will tell nobody about me. So you will live. If you do not do this, my friend will take your heart and liver out. You may lock your door, your may lie in bed, you may draw the clothes over your head, but that man will softly creep and creep his way to you and catch you. Now, what do you say?”

“I will bring you the file and some food. I will come to you early in the morning,” I answered.

“Now,” he said, “you remember what you promise, and you remember that man. Go home!”

“Good night, sir,” I faltered and ran away.

Chapter 2

My sister, Mrs. Joe Gargery, was more than twenty years older than I. She was not a good-looking woman. I think that she made Joe marry her[4].

Joe Gargery was a fair man, with curls of flaxen hair on each side of his smooth face, and with blue eyes. He was a mild, good-natured, sweet-tempered, easy-going, foolish, dear fellow. And he was very strong.

My sister was tall and bony, and almost always wore a coarse apron. It was fastened over her figure behind with two loops.

Joe’s forge adjoined our house, which was a wooden house. When I ran home from the churchyard, the forge was shut up. Joe was sitting alone in the kitchen. Joe and I were fellow-sufferers[5]. I raised the latch of the door and peeped in at him.

“Mrs. Joe is looking for you, Pip. And she’s out now.”

“Is she? How long, Joe?”

“Well,” said Joe, “about five minutes, Pip. She’s coming! Get behind the door, old chap[6].”

I took the advice. My sister came in.

“Where did you go, you young monkey?” asked she.

“I went to the churchyard,” said I.

I was crying and rubbing myself.

“Churchyard!” repeated my sister. “Churchyard, indeed! You’ll drive me to the churchyard, one of these days!”

My sister set the tea-things. She cut some bread and butter for us. But, though I was hungry, I dared not eat my slice. I was afraid of my dreadful acquaintance, and his ally, the more dreadful man.

It was Christmas Eve. My sister told me to stir the pudding for next day, with a copper-stick, from seven to eight. I decided to steal some food afterwards and bring it to my new “friend”. Suddenly I heard shots.

“Hark!” said I; “is it a gun, Joe?”

“Ah!” said Joe. “A convict ran away.”

“What does that mean, Joe?” said I.

Mrs. Joe said, snappishly, “Escaped.”

I asked Joe, “What’s a convict?”

“A criminal. That convict ran away last night,” said Joe, aloud, “after sunset. And they fired. They are warning of him. And now it appears they’re firing again because they are warning of another.”

“Who’s firing?” said I.

“Ask no silly questions,” interposed my sister, “what a questioner he is!”

It was not very polite, I thought. But she never was polite unless there was company.

“Mrs. Joe,” said I, “please tell me, where is the firing coming from?[7]”

“Lord bless the boy![8]” exclaimed my sister. “From the Hulks!”

“Oh-h!” said I, looking at Joe. “Hulks!”

“And please, what’s Hulks?” said I.

“Hulks are prison-ships[9]!” exclaimed my sister.

She pointed me out with her needle and thread, and shook her head at me,

“Answer him one question, and he’ll ask you a dozen directly!”

It was too much for Mrs. Joe. She immediately rose.

“I tell you, young fellow,” said she, “people are in the Hulks because they murder, and because they rob, and forge, and do all sorts of bad things. And they always begin by asking questions[10]. Now, you go to bed!”

She never allowed me to light a candle, and I went upstairs in the dark. Hulks! I was clearly on my way there. I began to asking questions, and I was going to rob Mrs. Joe.

But I was in mortal terror of the man who wanted my heart and liver. I was in mortal terror of my interlocutor with the iron leg. I was in mortal terror of myself, too.

In the early morning I got up and went downstairs. Every board upon the way, and every crack in every board were calling after me, “Stop thief!” and “Get up, Mrs. Joe!” I stole some bread, some cheese, about half a jar of mincemeat, some brandy from a bottle, a meat bone and a beautiful round compact pork pie.

There was a door in the kitchen. It communicated with the forge. I unlocked and unbolted that door, and took a file from among Joe’s tools. Then I opened the door at which I had entered when I ran home last night. I shut it, and ran away.

Chapter 3

It was a rimy morning, and very damp. The mist was heavier yet when I got out upon the marshes. Everything seemed to look at me. The gates and dikes and banks cried, “A boy with somebody’s else’s pork pie! Stop him!” The cattle came upon me. They were staring out of their eyes, and steaming out of their nostrils, “Halloa, young thief!”

All this time, I was getting on towards the river. I crossed a ditch, and scrambled up the mound beyond the ditch. Then I saw the man. He was sitting before me. His back was towards me. His arms were folded, he was nodding forward, heavy with sleep.

I went forward softly and touched him on the shoulder. He instantly jumped up. It was not the same man, but another man!

And yet this man was dressed in coarse gray, too, and had a great iron on his leg. All this I saw in a moment. I had only a moment to see it in. He ran into the mist, and I lost him.

Soon I saw the right Man, who was waiting for me. He was awfully cold. His eyes looked so awfully hungry too.

“What’s in the bottle, boy?” said he.

“Brandy,” said I. “I think you have got the ague,” said I.

“Sure, boy,” said he.

“It’s bad about here,” I told him. “You’re lying out on the meshes, and they’re dreadful aguish. Rheumatic too.”

“You’re not a deceiving imp? You brought no one with you?”

“No, sir! No!”

“Well,” said he, “I believe you.”

Something clicked in his throat. He smeared his ragged rough sleeve over his eyes.

“I am glad you enjoy the food,” said I

“What?”

“I said I was glad you enjoyed it.”

“Thank you, my boy. I do.”

He was eating like a large dog of ours. The man took strong sharp sudden bites, just like the dog.

“I am afraid you won’t leave any food for him,” said I, timidly.

“Leave for him? Who’s him?” said my friend.

“The man. That you spoke of[11].”

“Oh ah!” he said, with something like a gruff laugh. “Him? Yes, yes! He doesn’t want any food.”

“I thought he looked as if he did,” said I.

The man stopped eating. He regarded me with the keenest scrutiny and the greatest surprise.

“Looked? When?”

“Just now.”

“Where?”

“Yonder,” said I, and pointed; “over there, where I found him. He was sleeping, and I thought it was you.”

He held me by the collar and stared at me. I began to think his first idea to cut my throat revived again.

“Dressed like you, you know, only with a hat,” I explained. I was trembling. “Didn’t you hear the cannon last night?”

“Then there was firing!” he said to himself.

“He had a badly bruised face,” said I.

“Not here?” exclaimed the man. He stroke his left cheek mercilessly, with the flat of his hand.

“Yes, there!”

“Where is he?” He crammed little food into the breast of his gray jacket. “Show me the way he went. I’ll pull him down[12], like a bloodhound. But first give me the file, boy.”

I indicated the direction. He looked at me for an instant. But then he sat on the wet grass and began to file his iron like a madman. I told him I must go, but he took no notice.

Chapter 4

I expected to find a Constable in the kitchen. I was ready to go to the prison. But Mrs. Joe was prodigiously busy in the house. She was preparing for the festivities of the day.

We were going to have a superb dinner of a leg of pickled pork and greens, and a pair of roast stuffed fowls. A handsome mince-pie was made yesterday morning. The pudding was already on the boil.

We were waiting for Mr. Wopsle, the clerk at church, and Mr. Hubble[13] the wheelwright and Mrs. Hubble; and Uncle Pumblechook (Joe’s uncle), who was a cornchandler in the nearest town, and drove his own chaise-cart. The dinner hour was half-past one. Everything was most splendid. I heard not a word of the robbery.

The time came, and the company arrived. I opened the door to the company. I opened it first to Mr. Wopsle, next to Mr. and Mrs. Hubble, and last of all to Uncle Pumblechook.

“Mrs. Joe,” said Uncle Pumblechook, a large middle-aged slow man, with dull staring eyes, and sandy hair, “Mum, I have a bottle of sherry wine, and I have a bottle of port wine, too.”

Every Christmas Day he presented himself with exactly the same words.

We dined on these occasions in the kitchen. My sister was uncommonly lively on the present occasion. Indeed she was generally more gracious in the society of Mrs. Hubble than in other company.

Soon we sat down to dinner. Mr. Wopsle said a prayer: we must be truly grateful. My sister said, in a low reproachful voice,

“Do you hear that? Be grateful.”

“Especially,” said Mr. Pumblechook, “be grateful, boy, to them which brought you up[14].”

Mrs. Hubble shook her head and asked,

“Why are the young boys never grateful?”

Mr. Hubble answered,

“They are just vicious.”

Everybody then murmured “True!” and looked at me in a particularly unpleasant and personal manner.

“Listen to this!” said my sister to me, in a severe parenthesis.

“You must taste,” said my sister, addressing the guests with her best grace, “you must taste such a delightful and delicious present of Uncle Pumblechook’s! You must know, it’s a pie; a savory pork pie.”

My sister went out to get it. I heard her steps. She went to the pantry. Mr. Pumblechook balanced his knife. I wanted to run away. I stood up. But I ran no farther than the house door. There stood a party of soldiers with their muskets.

Chapter 5

The sergeant and I were in the kitchen when Mrs. Joe stared at us.

“Excuse me, ladies and gentleman,” said the sergeant, “but I am on a chase in the name of the king, and I want the blacksmith.”

“And why do you want him?” retorted my sister.

“Missis,” returned the gallant sergeant, “a little job. You see, blacksmith, we had an accident with handcuffs. The lock of one of them goes wrong, it doesn’t act pretty. We need immediate service, will you look at them?”

Joe looked at them and said,

“The job will take two hours.”

“Will you give me the time?” said the sergeant to Mr. Pumblechook.

“It’s just half past two.”

“That’s not so bad,” said the sergeant. “How far are the marshes? Not above a mile, I reckon?”

“Just a mile,” said Mrs. Joe.

“Convicts, sergeant?” asked Mr. Wopsle.

“Ay!” returned the sergeant, “two. They are out on the marshes, and we are going to catch them.”

At last, Joe’s job was finished. Joe got on his coat, and offered us to go down with the soldiers. Mr. Pumblechook and Mr. Hubble declined; but Mr. Wopsle was ready to go with Joe. Joe wanted to take me. What will say Mrs. Joe? Mrs. Joe said,

“If you bring the boy back with his head crushed, don’t ask me to put it together again.”

Soon we were all out in the raw air. We were steadily moving towards the marshs, and I whispered to Joe,

“I hope, Joe, we shan’t find them.”

Joe whispered to me,

“I hope too, Pip.”

The weather was cold and threatening, the way was dreary. The people had good fires and were celebtaring the day. A few faces looked after us from the windows, but none came out. We passed the finger-post, and held straight on to the churchyard. There we were stopped by a signal from the sergeant’s hand. Two or three of his men dispersed themselves among the graves, and examined the porch. They did not find anything. Joe took me on his back.

I looked all about for any sign of the convicts. Finally, I saw them both. The soldiers stopped.

After that they began to run. After a while, we heard a voice “Murder!” and another voice, “Convicts! Runaways! Guard! This way!” The soldiers ran like deer, and Joe too.

“Here are both men!” panted the sergeant. “Surrender, you two!”

Water was splashing, and mud was flying.

“Mind that!” said my convict. He wiped blood from his face with his ragged sleeves: “I took him! I give him up to you! Mind that!”

The other was bruised and torn all over.

“Take notice, guard – he tried to murder me,” were his first words.

“Tried to murder him?” said my convict, disdainfully. “Try, and not do it? I took him; that’s all, I dragged him here. He’s a gentleman, if you please, this villain. Now, the Hulks has got its gentleman again, through me!”

The other one still gasped,

“He tried – he tried to – murder me.”

“Look here!” said my convict to the sergeant. “I tried to kill him? No, no, no.”

The other fugitive, who was evidently in extreme horror of his companion, repeated,

“He tried to murder me!”

“He lies!” said my convict, with fierce energy. “He’s a liar, and he’ll die a liar. Look at his face. Do you see him? Do you see what a villain he is?”

“Enough,” said the sergeant. “Light those torches. All right. March.”

My convict never looked at me, except that once. He turned to the sergeant, and remarked,

“I wish to say something.”

“You can say what you like,” returned the sergeant, “but you’ll have opportunity enough to say about it, and hear about it, you know.”

“A man can’t starve; at least I can’t. I took some food, at the village over there[15].”

“You mean stole,” said the sergeant.

“And I’ll tell you where from. From the blacksmith’s.”

“Halloa!” said the sergeant, staring at Joe.

“Halloa, Pip!” said Joe, staring at me.

“It was some food – that’s what it was – and liquor, and a pie.”

“Do you miss a pie, blacksmith?” asked the sergeant, confidentially.

“My wife does, at the very moment when you came in. Don’t you know, Pip?”

“So,” said my convict, without the least glance at me, “so you’re the blacksmith, are you? I’m sorry. I ate your pie.”

“You’re welcome,” returned Joe, “we don’t know what you did before, but you must not starve, poor miserable fellow. Right, Pip?”

Something clicked in the man’s throat, and he turned his back.

I did not want to lose Joe’s confidence. I was staring drearily at my companion and friend. I was too cowardly to tell Joe the truth. As I was sleepy, Joe took me on his back again and carried me home.

Chapter 6

When I was old enough, I was to be apprenticed to Joe.

“Didn’t you ever go to school, Joe, when you were as little as me?” asked I one day.

“No, Pip.”

“Why didn’t you ever go to school?”

“Well, Pip,” said Joe; “I’ll tell you. My father, Pip, liked to drink much. So my mother and me we ran away from my father several times. Sometimes my mother said, ‘Joe, you must go to school, child.’ And she put me to school. But my father couldn’t live without us. So he came with a crowd and took us from the houses where we were. He took us home and hammered us.”

“Certainly, poor Joe!”

“My father said I must work. So I went to work. In time I was able to keep him, and I kept him till he went off.”

Joe’s blue eyes turned a little watery. He rubbed first one of them, and then the other, in a most uncongenial and uncomfortable manner, with the round knob on the top of the poker.

“I met your sister,” said Joe, “she was living here alone. Now, Pip,”Joe looked firmly at me; “your sister is very nice and clever.”

“I am glad you think so, Joe.”

“Yes,” returned Joe. “That’s it. You’re right, old chap! When I met your sister, she was bringing you. Very kind of her too, all the folks said, and I said, along with all the folks. When your sister was willing and ready to come to the forge, I said to her, ‘And bring the poor little child. God bless the poor little child,’ I said to your sister, ‘there’s room for him at the forge!’”

I hugged Joe round the neck. He dropped the poker to hug me and said,

“We are the best friends; aren’t we, Pip? Don’t cry, old chap!”

When this little interruption was over, Joe resumed:

“Well, you see; here we are! Your sister a master-mind.[16] A master-mind. However, here comes the mare!”

Mrs. Joe and Uncle Pumblechook were soon near. Then we were soon all in the kitchen.

“Now,” said Mrs. Joe, with haste and excitement, “if this boy isn’t grateful this night, he never will be! Miss Havisham wants this boy to go and play in her house. And of course he’ll go.”

I heard of Miss Havisham – everybody heard of her – as an immensely rich and grim lady. She lived in a large and dismal house and led a life of seclusion[17].

“But how did she know Pip?” said Joe, astounded.

“Who said she knew him?” cried my sister. “She just asked Uncle Pumblechook if he knew of a boy to go and play there. Uncle Pumblechook thinks that that is the boy’s fortune. So he offered to take him into town tonight in his own chaise-cart, and to take him with his own hands to Miss Havisham’s tomorrow morning.”

I was then delivered over to Mr. Pumblechook. He said:

“Boy, be forever grateful!”

“Good-bye, Joe!”

“God bless you, Pip, old chap!”

I never parted from him before. I did not understand why I was going to play at Miss Havisham’s, and what to play at.

Chapter 7

Mr. Pumblechook and I breakfasted at eight o’clock in the parlor behind the shop. I didn’t like Mr. Pumblechook. He said, pompously,

“Seven times nine, boy?[18]”

I was very hungry, but the math lesson lasted all through the breakfast.

“Seven?” “And four?” “And eight?” “And six?” “And two?” “And ten?” And so on.

For such reasons, I was very glad when ten o’clock came and we started for Miss Havisham’s. Miss Havisham’s house was of old brick, and dismal, and had many iron bars. While we waited at the gate, Mr. Pumblechook said, “And fourteen?” but I did not answer.

A window was raised, and a clear voice demanded,

“What name?”

My conductor replied,

“Pumblechook.”

The voice returned, “Quite right,” and the window was shut again. Then a young lady came across the courtyard, with keys in her hand.

“This,” said Mr. Pumblechook, “is Pip.”

“This is Pip, is it?” returned the young lady, who was very pretty and seemed very proud; “come in, Pip.”

Mr. Pumblechook was coming in also, when she stopped him.

“Oh!” she said. “Did you wish to see Miss Havisham?”

“If Miss Havisham wished to see me,” returned Mr. Pumblechook, discomfited.

“Ah!” said the girl; “but you see she didn’t.”

Mr. Pumblechook did not protest. My young conductress locked the gate, and we went across the courtyard. It was paved and clean, but grass was growing in every crevice. The cold wind seemed to blow colder there than outside the gate.

“Now, boy, you are at the Manor House,” said the girl.

“Is that the name of this house, miss?”

“One of its names, boy.”

She called me “boy” very often, but she was of about my own age. Anyway, she seemed much older than I, of course.

We went into the house by a side door. The great front entrance had two chains across it outside. The passages were all dark. At last we came to the door of a room, and the girl said, “Go in.”

I answered, more in shyness than politeness, “After you, miss.”

To this she returned:

“Don’t be ridiculous, boy; I am not going in.”

She scornfully walked away, and took the candle with her.

This was very uncomfortable, and I was afraid. However, I knocked and entered. I found myself[19] in a large room. It was well lighted with wax candles. No glimpse of daylight. It was a dressing-room, but in it was a draped table with a gilded looking-glass.

In an arm-chair, sat a very strange lady. She was dressed in rich materials – satins, and lace, and silks – all of white. Her shoes were white. And she had a long white veil dependent from her hair. She had bridal flowers in her hair, but her hair was white. Some bright jewels sparkled on her neck and on her hands, and some other jewels lay on the table.

“Who is it?” said the lady.

“Pip, ma’am.”

“Come nearer; let me look at you. Come close.”

A clock in the room stopped at twenty minutes to nine.

“Look at me,” said Miss Havisham. “You are not afraid of me?”

“No.”

“Do you know what I touch here?” she laid her hands, one upon the other, on her left side.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“What do I touch?”

“Your heart.”

“Broken!”

She uttered the word with strong emphasis, and with a weird smile.

“I am tired,” said Miss Havisham. “I want diversion. Play. I sometimes have sick fancies. There, there!” with an impatient movement of the fingers of her right hand; “play, play, play!”

I was looking at Miss Havisham.

“Are you sullen and obstinate?”

“No, ma’am, I am very sorry for you, and very sorry I can’t play just now. It’s so new here, and so strange, and so fine and melancholy…”

Before she spoke again, she turned her eyes from me, and looked at the dress she wore, and at the dressing-table, and finally at herself in the looking-glass.

“So new to him,” she muttered, “so old to me; so strange to him, so familiar to me; so melancholy to both of us! Call Estella.”

As she was still looking at the reflection of herself, I thought she was still talking to herself.

“Call Estella,” she repeated. “You can do that. Call Estella. At the door.”

I called Estella. Soon her light came along the dark passage like a star. Miss Havisham beckoned her to come close, and took up a jewel from the table.

“Your own, one day, my dear, and you will use it well. Let me see you play cards with this boy.”

“With this boy? Why, he is a common laboring boy[20]!”

Miss Havisham answered,

“Well? You can break his heart.”

“What do you play, boy?” asked Estella, with the greatest disdain.

“Nothing but beggar my neighbor[21], miss.”

“Beggar him[22],” said Miss Havisham to Estella.

So we sat down to cards. The lady was corpse-like, as we played.

“What coarse hands he has, this boy!” said Estella with disdain. “And what thick boots!”

Her contempt for me was very strong. She won the game, and I dealt. I misdealt, and she called me a stupid, clumsy laboring-boy.

“You say nothing of her,” remarked Miss Havisham to me. “She says many hard things of you, but you say nothing of her. What do you think of her?”

“I don’t like to say,” I stammered.

“Tell me in my ear,” said Miss Havisham.

“I think she is very proud,” I replied, in a whisper.

“Anything else?”

“I think she is very pretty.”

“Anything else?”

“I think she is very insulting.”

“Anything else?”

“I want to go home.”

“And never see her again, though she is so pretty?”

“I am not sure. But I want to go home now.”

“You will go soon,” said Miss Havisham, aloud. “Play.”

I played the game to an end with Estella, and she beggared me. She threw the cards down on the table.

“When shall I have you here again?” said Miss Havisham. “Let me think. Come again after six days. You hear?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Estella, take him down. Let him have something to eat. Go, Pip.”

I followed the candle down. Estella opened the side entrance.

“Wait here, you boy,” said Estella.

She disappeared and closed the door.

She came back, with some bread and meat and a little mug of beer. She put the mug down on the stones of the yard, and gave me the bread and meat. She did not look at me. I was so humiliated, hurt, spurned, offended, angry. Tears started to my eyes. The girl looked at me with a quick delight, then she left me.

I looked about me for a place to hide my face in and cried. As I cried, I kicked the wall.

Then I noticed Estella. She laughed contemptuously, pushed me out, and locked the gate upon me. I went straight to Mr. Pumblechook’s. Then I walked to our forge. I remembered that I was a common laboring-boy; that my hands were coarse; that my boots were thick.

Chapter 8

When I reached home, my sister was very curious to know all about Miss Havisham’s. She asked many questions. Then old Pumblechook came over at tea-time.

“Well, boy,” Uncle Pumblechook began, as soon as he was seated in the chair of honor[23] by the fire. “How did you get on up town?[24]”

I answered, “Pretty well, sir,” and my sister shook her fist at me.

“Pretty well?” Mr. Pumblechook repeated. “Pretty well is no answer. Tell us what you mean by pretty well, boy?”

“I mean pretty well,” I answered.

My sister was ready to hit me. I had no defence, for Joe was busy in the forge. Mr. Pumblechook interposed,

“No! Don’t lose your temper. Leave this lad to me, ma’am; leave this lad to me.”

Then Mr. Pumblechook turned me towards him and said,

“Boy! Tell me about Miss Havisham.”

“She is very tall and dark,” I told him.

“Good!” said Mr. Pumblechook conceitedly. “Now, boy! What was she doing, when you went in today?”

“She was sitting,” I answered, “in a black velvet coach.”

Mr. Pumblechook and Mrs. Joe stared at one another and both repeated,

“In a black velvet coach?”

“Yes,” said I. “And Miss Estella – that’s her niece, I think – brought her some cake and wine.”

“Was anybody else there?” asked Mr. Pumblechook.

“Four dogs,” said I.

“Large or small?”

“Immense,” said I.

Mr. Pumblechook and Mrs. Joe stared at one another again, in utter amazement.