Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Periscope

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Wry, satirical and bawdy, Tamer's stories are always informed by his dark view of humanity and of Syrian society in particular. Through these glimpses of corrupt, fearful lives under a violent dictatorship, it is possible to discern echoes of the storm that has brought Syria to near-disintegration. Tamer's stories explore taboos and power relations, bringing together religion, politics and sexuality (often all at once) and implying that these forms of oppression are connected. An assault is deflected when the victim responds enthusiastically; a woman is spared stoning because the streets have no cobbles, and her neighbours cannot afford any; A comatose man awakens after years to find the regime unchanged, and tries to escape back into the coma; a newborn baby curses the hospital staff that delivers him, and when his mother tries to quiet him, retorts: 'You're talking like our leaders!'; a man is warned by two apples not to eat them, and anxiously questions them about their political connections. Unsentimental and brilliantly compressed, these sixty-three stories are the work of a virtuoso, and translator Ibrahim Muhawi has found exactly the right deadpan style with which to express them.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 198

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

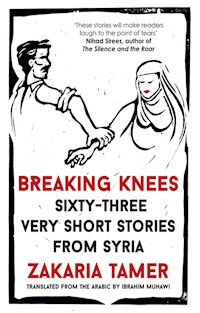

Breaking Knees

Sixty-three Very Short Stories from Syria

Zakaria Tamer

Translated from the Arabic by Ibrahim Muhawi

Breaking Knees

Sixty-three Very Short Stories from Syria

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Periscope

An imprint of Garnet Publishing Limited

8 Southern Court, South Street

Reading RG1 4QS

www.periscopebooks.co.uk

www.facebook.com/periscopebooks

www.twitter.com/periscopebooks

www.instagram.com/periscope_books

www.pinterest.com/periscope

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Copyright © Zakaria Tamer, 2008

Translation copyright © Ibrahim Muhawi, 2008

The right of Zakaria Tamer to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

ISBN 9781902932460

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book has been typeset using Periscope UK,

a font created specially for this imprint.

Typeset bySamantha Barden

Jacket design by James Nunn: www.jamesnunn.co.uk

Printed and bound in Lebanon by International Press: [email protected]

Acknowledgments

A Lannan Foundation residency (in Marfa, Texas) gave me the opportunity to start work on this translation during the summer of 2004. I am happy to acknowledge the contribution of the Foundation and its staff to the welfare of this project. Martha Jessup provided intellectual support and Douglas Humble looked after my welfare while in Marfa. The work was finished with the support of the International Center for Writing and Translation at the University of California, Irvine. I am grateful to the Center for the award of one of its 2006–2007 translations grants, and to Professors Ammiel Alcalay, James Monroe, and Yasir Suleiman for their recommendations. Rick London and Sid Gershgoren read parts of the manuscript and offered many valuable suggestions. The unqualified support of Dan Nunn of Garnet Publishing was essential to the process of publication.

The contribution of my wife Jane Muhawi (whom in a previous acknowledgement I called “my native ear”) is more than can be put into words. Her superb command of the language and her ear for nuance have boosted my confidence in producing a translation that (I feel) does justice to the Arabic original.

Ibrahim Muhawi

Introduction

Zakaria Tamer (b. 1931 in Damascus) is acknowledged as one of the great writers of the modern Arab world. His writing covers a range of literary forms, including stories for children and satirical reflections on Arab affairs that first appeared as newspaper columns and were later collected into separate volumes. His literary stature and influence, however, rest on the type of very short story (al-qissa al-qasira jiddan) included in this work. The first volume of these (Neighing of the White Stallion) came out in 1960 and this work, which is the tenth, in 2002 under the title Taksir Rukab (Breaking Knees). The eleventh, The Hedgehog: A Story (2005), is a set of twenty-two tales that recount the experiences of a single character, a highly imaginative child. Tamer’s fecund imagination and his unique and productive pen will not allow him to rest on his laurels. The next volume of stories is already in the making, and I’m sure others (as well as the stream of newspaper columns) will follow for as long as he lives.

Tamer has often been referred to as a master of the short story, but this is not an entirely accurate description. True, the (very) short story is his preferred form, but he hardly ever publishes these separately. His usual practice is to publish a collection as a single work revolving around a set of themes. The fact that Tamer subtitles The Hedgehog “a story,” though composed of twenty-two individual tales, is clear indication that he wishes us to read his books as artistic units. We see this process at work in the present volume as well, where the stories do not have names but numbers. This is an important point to bear in mind while reading Breaking Knees. Each story can stand on its own, yet there are underlying (and frequently quite subtle) connections of theme, style, and perspective that knit the work together in the reader’s mind long after the book has been read. Actually, the format of the book encourages frequent reading. The work is too intense to be read at one sitting, but the seemingly endless inventiveness in plot and the underlying humor of the writing will keep readers curious as to what the author will be up to next.

Tamer is a satirist, and the target of his satire is the Arab world – its culture, politics, social practices, and dominant religion. In case we have any doubts about what he is doing, he himself tells us directly. To a collection of short essays written at various times but published in 2003 he has given the title The Victim Satirizes His Killer: Short Essays. The title tells it all, the victim being the citizen; the killer, the state; and the literary mode, satire. The comment on the back cover of the book declares its intention. It says in part: “Countries in which there is no room for criticism are poor and miserable, worthy of being lambasted, lamented, and held up to ridicule . . . This book . . . is a modest attempt to offer some criticism of all that holds people down and retards their development and their enjoyment of their right to a life free of fear . . .”

The general theme of Breaking Knees, as of much of Tamer’s work, is repression: of the individual by the institutions of state and religion and of individuals by each other, particularly women by men. Thus the question of authority – political, social, sexual, and religious – forms the thematic core of the book, with (female) sexuality receiving the lion’s share of concern. Political authority is manifest in the emphasis in many stories on the machinations of the police state – arbitrary arrest and detention, interrogations, corruption. Social authority expresses itself in the patriarchal cultural order and the dominance of religious and cultural institutions and conventions that constrain individual freedom. Many stories stress religious hypocrisy and the unfulfilled sexual expectations of women. In some the marriage bed is associated with a place of death for women. Breaking Knees is a daring work of art that deals with taboo subjects like religion and female sexuality in a frank manner and expresses an urgently felt need for change.

In bringing together religion, politics, and sexuality (sometimes all three in the same story) the author is telling us indirectly that these forms of oppression are all connected. There is a malaise at the core of the traditional Arab psyche, perhaps at the core of Arab culture itself, that accounts for the aberrant behavior of many of many of Tamer’s characters. From the perspective of the countless Arab individuals who have adopted modern values based on democratic institutions and human rights, a state of affairs characterized by political and cultural stagnation, destructive worship of tradition, and glorification of a mythical past, appears truly dire. To understand Tamer’s satiric method and the complexity of his narrative vision, we have to put his work in the context of this malaise.

It would be a mistake, of course, to focus solely on the activist, political aspect of these stories at the expense of appreciating them as literature – that is, as discourse that through the particular reaches for the universal. Tamer extends the boundaries of what is possible in fiction. His art is based on a radical questioning of what is usually taken to be “reality” in a work of fiction. His work alerts us to the extent that we as readers come to any story armed with a set of assumptions about the protocols of narrative, such as plot, character, continuity, plausibility, and probability. All these conventions are challenged, and frequently broken. Those who read fiction for comfort must prepare to be shocked at this unrelenting assault on their expectations. Tamer’s fictional world often draws on the world of the dream to confuse the boundaries of the real and the imagined, or even the boundary between life and death: a house can be a character, so can an apple, a cat, a statue, a dead (or seemingly dead) person, as well as the angels and the jinn. Temporality in his stories does not always conform to the ordinary perception of the forward movement of time: a character’s life, for example, may not necessarily end with his or her death. Characters who have died, or ghost-like characters who can only be described as the living dead, continue to exercise a palpable influence on the world of the living.

Though this surreal world is rather rare in written fiction, it characterizes the animistic and mythological world of the folktale (the universal form of narrative par excellence) where everything has a voice and can speak, where time is indeterminate, and space has flexible boundaries. The natural world is suffused with the supernatural, and what takes place does not necessarily conform to expectations. The purpose of fantasy and wonder in folktales is to appeal to the imagination of children, which is more active than that of adults. Tamer draws on the childhood experience of orally recited tales to challenge our comfortable accommodation with the world. The pleasure of reading these stories will be heightened if readers remain alert to the ways in which they touch base with the art of the oral tales, especially the manner in which folktales transform the world of ordinary perception into that of the imagination.

In this work the universal takes many forms, the most important being the theme of gender identity and conflict, a ubiquitous subject in literature going all the way back to the myth of the Garden of Eden. The opening allegory of the book (itself a major literary form in all literature) announces this theme. Perhaps the patriarchal social order that prevails in most Arab countries gives the subject of gender identity and conflict an additional poignancy, but its significance for literature in general arises from its reach into practically all aspects of life, from the level of personal identity to that of social interaction and culturally determined modes of behavior. From this great subject arise subsidiary themes that endow literature with a moral dimension. I am thinking here of passion, desire, identity, and love of self which animate much individual behavior in these stories.

There are no wasted words in Tamer’s musical prose. His descriptions, whether of the environment or of his characters, are always precise and to the point. Since these stories are very short, the writer must get to the action immediately by setting his scenes in familiar environments, like the home, the coffee house, the fields, an orchard, or the street. Though very short the stories are not incomplete. Each offers a psychological portrait that does not challenge credibility. The author does this by means of a number of devices. I have already alluded to a reversal of the relationship between the “real” and the “fictional,” yet Tamer uses reversal in a number of other ways as well. He may aim to shock or demonstrate the absurdity of social or gender roles by reversing them. The most shocking for a male-oriented culture would be the reversal of the masculine and feminine that occurs in several stories, with men consciously assuming or being forced into roles and positions usually assigned to women. Sometimes reversal is subtly introduced within the texture of the writing itself when the narrative point of view shifts without warning from the subjective to the objective, allowing more than one voice to speak within the same sentence. The embedded voice, the voice within the voice, also acts like a story within the story, giving us more than one narrative in each story. While the presence of these multiple voices adds psychological depth to the narrative, it also serves to alienate readers from a comfortable relationship with the text, because there is no single voice that speaks through it. The devices I have just mentioned, along with a highly imaginative reliance on metaphor, give these stories a unique form of psychological realism which I call the realism of gesture.

The satirical mode itself also gives this work a universal dimension, for when successfully practiced satire functions within the framework of a sophisticated world literary culture. There may be a problem with contemporary Arab culture and the Arab political system, but literature has always been highly valued by the Arab people, and Arabic literature, though not so well-known in the “West,” forms one of the world’s great literary traditions, with a history that goes back to well before the rise of Islam in the early seventh century C.E. Historically satire (hija’ ) has been responsible for some of the greatest works of Arabic literature. Yet satirical fiction does not work on its own: it needs irony, which is another universal mode of organizing literary discourse. Irony lightens the air of seriousness by putting some distance between the author and his words. Without irony, which introduces a subtle undertone of wonder into the writing, a satirical author might sound like a moralizer and end up losing the reader. At the same time irony introduces another level of complexity in the narrative voice. If we compare irony to counterpoint in music, then we can see how it acts in concert with Tamer’s narrative to enable him to speak in more than one voice at the same time. In Tamer’s work we have to see the beauty in the pattern, where we find themes and variations everywhere we turn. The logic of each set of variations is a kind of dialog between what is possible and what is not possible once the assumptions underlying the opening actions are granted.

Tamer is a great prose stylist of the Arabic language, and here is where the challenge in translating him lies. His prose is poetic in its economy – lucid syntax, characterized by precision in the choice of words coupled with sentences that are very much aware of their rhythms. In a novel, or in more conventional short stories, even if the translation suffers from lapses, the translator can always rely on the fictional element to get the meaning across. But Tamer’s stories, as I have tried to show here briefly, represent a perfect union of meaning and form in which the performative role of language is part of the satirical meaning. A translation that is not aware of these values and does not make sufficient effort to transfer them to English will, in my opinion, do more harm than good. The choice of words must be managed in such a way that their range of signification always remains under reasonable control, with – if possible – no proliferation of nuances. Each word must be absolutely the right word for the context, and, equally importantly, the rhythm of the prose must dance in English as it does in Arabic. I have tried my best to replicate these values in English. The challenge was to produce an idiomatic and fluent rendering that is sensitive to the sound values of English yet remains as close to the literal meaning of the original as possible. I have therefore aimed for a text that is transparent enough to allow readers to peek through to the original, while at the same time remaining fluent enough to help them forget that what they are reading is a translation. I paid very careful attention to the rhythm of the prose with its measured and nuanced repetition of adjectives, which I have reproduced – sometimes sacrificing fluency for their sake – because repetition is one of the hallmarks of an elegant Arabic prose style. Yet it was not always possible to maintain the rhythmic repetition at the level of the clause, but even here all changes in rhythm were kept to an absolute minimum.

Tamer has been translated into a number of languages (English, German, Russian, Serbian, and Spanish), but he is not as well-known among international readers as he deserves to be, given his achievement. In English he is represented principally by Tigers on the Tenth Day And Other Stories (1985), which consists of twenty-four stories that were selected by the translator but which did not originally appear together in a single volume. It is my hope that a fresh translation of a recent complete work based on the principles mentioned above will help open a space for Tamer among the reading public in the English-speaking world, encouraging others to translate more of this superb and highly imaginative body of work.

Ibrahim Muhawi, Eugene, OR (USA)

1

The rains were scant. People appealed for help to a saintly man whose prayers were often heard, and a strange, heavy rain fell such as had not been seen before. One drop falling on a man made that which men have, but not women, grow bigger. And one drop falling on a woman made her breasts and buttocks swell. Women were happy, for the real thing was not like the artificial, and cosmetic surgery was very expensive. Men celebrated this correction, which made a trunk out of a branch, but some were not content with what they got for free. They asked for a rain that taught proper manners to any man stupid enough to think that size exempted him from having to rise for a woman.

Women prayed for a sudden rain that would make them pregnant and able to give birth without men. Men became idle, and found only dismissal, contempt, and derision wherever they went. Women then fell upon women, and men upon men.

2

Fuad was a man in no way different from other men. His heart almost stopped beating when he saw a beautiful woman. He told elegant Aisha he loved her. He told dark Sabah he loved her very much. He told blonde Nahla he loved her utterly. He told fair Hanan he loved her till death. And he told plump Fadwa his love was forever. Each of them had a different response, but they agreed without having met that he was not the valiant warrior who had it in him to pluck victory from decisive battle. Fuad kept away from these five women, but he realized that to win a woman he had to add a dash of polite daring to his conversation.

Staring at the bosom of fiery Maryam, he said, “I like to climb mountains.” He stared at her belly and said, “And I like to go down into valleys.” But with a frown on her face Maryam said in an angry voice, “I see you’re an idle fellow, content only with words without climbing mountains or going down into valleys.”

Fuad was now convinced women had changed. They had become warped and unfit for virile men. He married Raifa, who had dug deep into the earth for a man who would marry her, but they had not been married one week when she asked for a divorce. Her friends found that strange and pressed her to tell them the particulars, but she smiled slyly and said her husband was fond of standing in front of the mirror. She said she heard thunder and saw lightning, but no rain fell.

3

The woman and her husband were preparing to go to sleep in the darkness of night. In a soft voice, the woman said to her husband, “All the women I know love the nighttime. But I can’t stand the night. Can you guess why?”

“Because at night you like to lie on your stomach,” he answered without hesitation, “and I make you lie on your back.”

She then lay on her stomach and said in a trembling voice, “Why don’t you try to convince me of the beauties of the night, for I am a woman who doesn’t hold extreme views and am willing to listen to opinions supported by arguments and proofs.”

In a broken, gasping voice he spoke to her of the night. Outside cold winds were blowing, and the wife clung to her husband more closely. She said the wood in the heater had burned itself out and more was needed. He did not rush to bring wood but carried on as if the man were the wood and the woman the heater.

4

The three boys paid no heed to the burning midday sun and kept playing in the desolate alley, making enough noise for twenty. A man looked out of a window and shouted in an irate and vexed voice, “Calm down, you devils. We’re trying to get some rest.”

It was clear that the boys knew the man who had yelled at them, and feared him. One of them said, “Whatever you say, Abu Salim, whatever you say!”

They did not carry on with their playing but leaned against the wall and talked resentfully about school. They cursed the teacher who had failed them. The first boy said, “The Minister of Education himself is a friend of my parents, and never goes against my mother’s wishes. He will go berserk when he hears what has happened, and will kick the teacher out of the school.”

The second boy said, “The chief of police – he’s close to my older sister and spoils me. Every time he visits, he sends me out to buy myself some cake or chocolate. I’ll tell him our teacher is fat and lazy. He curses the government in front of us, and he sleeps in class and snores, and lets us do whatever we want.”

The third remained silent, while his friends gazed at him in anticipation. He tried to speak, but had nothing to say. His mother did not know any men other than his father, and his sisters did not know anyone other than their husbands. He was filled with confusion, and felt he had failed a second time.

5

Hasan waited to marry until he had found an inexperienced woman, in order to be the first and last man in her life. And he married none other than the woman he was confident he had been seeking for many long years. No sooner were they alone on their first night than she swiftly helped him remove his clothes, and cried out in surprise. “The creator be praised!” she exclaimed as she gaped at him. “I used to think the little finger was on the hand and the little toe on the foot, but it seems I was wrong.”

Hasan smiled with pleasure and pride, and his conviction grew that his wife was in fact the naïve and innocent woman he had been searching for.

6

Lama was accustomed to dozing off and putting in her mouth whatever happened to be in her hand. Her mother advised her in an angry and reproachful voice to get rid of her nasty habit, especially now that she was engaged and about to be married. But after marriage Lama discovered that her mother was naïve and that her advice was wrong, for what she had grown used to doing while dozing was widespread, prized, and desirable.