Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

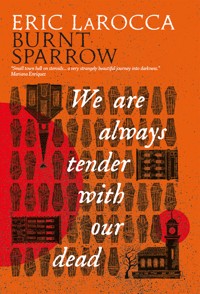

Michael McDowell's Blackwater meets Clive Barker's The Great and Secret Show in the disturbing first installment of a new trilogy of intense, visceral, beautifully written queer horror set in a small New England town. A chilling supernatural tale of transgressive literary horror from the Bram Stoker Award® finalist and Splatterpunk Award-winning author of Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke. The lives of those residing in the isolated town of Burnt Sparrow, New Hampshire, are forever altered after three faceless entities arrive on Christmas morning to perform a brutal act of violence—a senseless tragedy that can never be undone. While the townspeople grieve their losses and grapple with the aftermath of the attack, a young teenage boy named Rupert Cromwell is forced to confront the painful realities of his family situation. Once relationships become intertwined and more carnage ensues as a result of the massacre, the town residents quickly learn that true retribution is futile, cruelty is earned, and certain thresholds must never be crossed no matter what. Engrossing, atmospheric, and unsettling, this is a devastating story of a small New England community rocked by an unforgivable act of violence. Writing with visceral intensity and profound eloquence, LaRocca journeys deep into the dark heart of Burnt Sparrow, leaving you chilled to the bone and wanting more.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 365

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Two Burnt Sparrow Residents Die In House Fire On Swampscott Road

Diary Entry Written By Rupert Cromwell

Rupert Cromwell

In A Lonely Place: The Unusual History of the Town of Burnt Sparrow, New Hampshire

Gladys Esherwood

Rupert Cromwell

Gladys Esherwood

What Ever Happened To Amaya Richards? The Disappearance of A Burnt Sparrow Toddler

Diary Entry Written By Rupert Cromwell

Rupert Cromwell

Gladys Esherwood

Rupert Cromwell

Ten-Letter Word for Pernicious: The Gruesome Account of One of Burnt Sparrow’s Most Unexplained Murders

Rupert Cromwell

Diary Entry Written By Rupert Cromwell

Gladys Esherwood

Rupert Cromwell

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise for

WE ARE ALWAYSTENDER WITH OUR DEAD

“This is small town hell on steroids: Burnt Sparrow is somewhere around the corner that you never want to even pass by. The beautiful writing of Eric LaRocca makes this tale of grief, violence and perversion (a lot of it) a very strangely beautiful journey into darkness. It reminds me of Poppy Z. Brite at her most brutal, vile and best. Unflinching and relentless body and social horror, with a nod to Derry and unspeakable desire.”

MARIANA ENRIQUEZ, author of Our Share of Night and A Sunny Place for Shady People

“Not since Twin Peaks has there been a town quite like Burnt Sparrow, where nightmares, secrets, cruelty, and longing are the currency. Your visit will be harrowing and it will cut you to the quick, but you’ll want to return as soon as possible.”

PAUL TREMBLAY, author of Horror Movie and A Head Full of Ghosts

“The Poet Laureate of Pestilence, Eric LaRocca, impales his readers on the white picket fences of David Lynch country with We Are Always Tender with Our Dead, shifting his transgressive eye toward the toxic-bucolic small town of Burnt Sparrow, where he summons a particular poetry in tragedy, transcendence in grief, and elegance in the most brutal of violence.”

CLAY MCLEOD CHAPMAN, author of Wake Up and Open Your Eyes and What Kind of Mother

“Eric LaRocca is one of the best horror voices to emerge in the last few years. We Are Always Tender with Our Dead is his finest work to date, filled with relentless darkness, but beauty too. The story and characters will stay with you in your dreams long after you’ve finished it.”

RICHARD KADREY, author of The Pale House Devil and the Sandman Slim series

“Blending the grotesque and the sublime, We Are Always Tender with Our Dead moves with the callous logic of a nightmare. LaRocca initiates us into his newest trilogy with a haunting meditation on affliction, grief, and the darkness that lurks beneath the bonds that tie—or trap—the residents of Burnt Sparrow to one another.”

ELLE NASH, author of Deliver Me and Gag Reflex

“With We Are Always Tender with Our Dead, Eric LaRocca adds to his already remarkable body of work. Wielding his graceful prose with the deftness of a surgeon holding a scalpel, LaRocca cuts to the beating, bloody heart of a small New England town shocked by an act of unexpected brutality, then examines the network of consequences that results. In the process, he finds savagery, sorrow, beauty, and much, much more. The first in a trilogy, this novel signals an exciting new phase in Eric LaRocca’s fiction. I can’t wait for what comes next.”

JOHN LANGAN, author of Lost in the Dark and Other Excursions and The Fisherman

“LaRocca is a maestro of the horrific, surreal, and uncanny, and his work never fails to illuminate the dark epicenter of the human condition while offering the suggestion of hope—maybe. Every tale is one that will leave you shaking and breathless, yet like a car wreck, you’re helpless to look away.”

RONALD MALFI, author of Senseless and Come With Me

Dear kindhearted reader,

When I first approached Titan Books with the formal proposal of We Are Always Tender with Our Dead (Burnt Sparrow Book 1), I assured my editor that I would handle the very graphic subject matter I had planned to write with the utmost delicateness and sensitivity.

I regret to inform you, dear reader, that I have failed miserably.

However, I’m afraid I was always destined to fail in such a way when conveying these brutal and unpleasant subjects. There is nothing tasteful about incest, violence, and rape. These are truths of our existence—unpleasant matters that remain ubiquitous to our collective suffering as a species. Anyone who says they can write about such things with sensitivity and care is lying. These transgressions are not tasteful by their very nature. Of course, you may disagree; however, that’s how I feel as an artist, as an author of horror fiction.

Therefore, it’s my unfortunate task to warn you that the book you are about to read is profoundly distasteful. It’s certainly not a book that can (or even should) be enjoyed. At least not in the traditional sense. This novel contains graphic depictions of body horror, incest, sexual assault, animal cruelty, gun violence, murder, necrophilia, child sexual abuse, violent death of an infant, domestic abuse, torture, and bereavement.

I have been encouraged by my very thoughtful editor to warn readers early on in case they might like to avoid such nastiness. If these things disturb enough to give you pause, I highly encourage you to seek entertainment elsewhere. This novel is not intended to entertain. I never set out to amuse or enthrall with my fiction. Instead, I hope to provoke, to elicit a reaction from my audience.

If you are willing to join me, I thank you for your time and I sincerely look forward to greeting you on the other side.

ERIC LAROCCA

Newmarket, NHNovember 2024

ALSO BY ERIC LAROCCAAND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spokeand Other Misfortunes

The Trees Grew BecauseI Bled There: Collected Stories

Everything the Darkness Eats

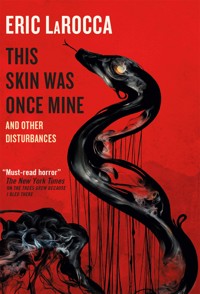

This Skin was Once Mineand Other Disturbances

At Dark, I Become Loathsome

ANTHOLOGIES FEATURING ERIC LAROCCAAVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS:

Bound in Blood

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Burnt Sparrow: We Are Always Tender with Our Dead

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781803368672

Signed Hardback edition ISBN: 9781835415764

Broken Binding edition ISBN: 9781835416679

Abominable Book Club edition ISBN: 9781835416686

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803368689

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Eric LaRocca 2025.

Eric LaRocca asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, [email protected], +3375690241

Set in Adobe Garamond by Richard Mason.

For Brian EvensonA mentor, an inspiration, a dear friend

The threshold is the place to pause.

—GOETHE

TWO BURNT SPARROW RESIDENTS DIE IN HOUSE FIRE ON SWAMPSCOTT ROAD

Published March 3, 2004, in The Burnt Sparrow Gazette

Written by George McDowell, News Staff Reporter

Torch Darling (34) and Ruskin Cave (29) are reported to have perished in a house fire on Swampscott Road in the early hours of the morning on Tuesday, February 24. Both men were Burnt Sparrow residents.

The victims were found unconscious, kneeling together in the first-floor parlor when firefighters entered the house at about 2:45 a.m., officials said. At that time, Cave was declared dead on the scene. However, it’s reported that Darling had a slight pulse when they inspected him. He was immediately rushed to a nearby hospital where he later died.

No cause of the fire has been determined yet. Autopsies will be performed on both men to determine the exact cause of death, said Fire Marshall Peter Blackwell.

The house belonged to Darling’s grandfather named Henley Darling, who had passed away a few months prior to last Tuesday’s house fire.

Torch Darling lived in the house by himself and hadn’t worked in a long time, according to neighbors. He was also almost completely blind, they said, and seemed to have psychological problems.

Officials are investigating whether there was a third victim present at the time of the house fire.

“There are traces of a possible third party involved,” Blackwell said. “Whether they started the fire and then fled the scene is uncertain. We’re still investigating the area.”

Blackwell also reports that his crew has uncovered a very peculiar imprint of a large bird seared into the remnants of the house.

Neighbors report that before his passing, Henley Darling purchased a rare bird from an exotic pet shop in the Boston area. Although the bird’s remains have not yet been recovered, it’s presumed that the creature perished in the fire as well.

Diary Entry Written By

RUPERT CROMWELL

March 26, 2004

I don’t wish to confess anything to you. A confess ion implies that there’s a semblance of guilt to be felt, a pang of humiliation to be to le rate d for the sake of proper contrition. It implies I should crave to be absolved, to be forgiven for what I am, all I’ve done. I’m here to tell you there’s nothing in this world that deserves my shame, my reflection, or my disgrace.

Perhaps once I might have deceived you and told you that I felt such embarrassment for how I’ve been perceived by others. Yes, even by people who claimed that they loved me. I might have told you how I owed them an explanation for my strangeness. I might have told you how I would give anything to bring them the honor they so rightfully deserve, the integrity that only a young man can offer his family. But such a statement would be utter trickery. I cannot bring myself to tell you those things and make you think that I believe I’m at fault, that I’m some lowly, reprehensible thing, undeserving of the grace of a gentler person’s forgiveness. I have spent so many years attempting to be tender in a world that will never understand softer language s like quietness, compassion. Perhaps once the world might have indulged in those kinds of whims, but it utterly refuses them now. Probably because soft things are easy to break. Moreover, soft things are so pleasing to break. It makes you feel like a stronger, more powerful person. That’s how everyone wants to feel, especially when things see m so uncontrollable. We all want to feel as though we have the upper hand, that we have somehow evaded the callous, careless deity presiding over human affairs and have instead found meaning or purpose in all this exquisite pointlessness.

I regret to tell you there’s nothing really to be found there. It’s an empty sacrifice. There’s nothing in this world that has meaning or shares any value. I’ve already been taught that human life holds no significance. It’s sad to think how a corpse is very often worth more than a living thing. At least there’s some value left in a dead body, however little, however insignificant. But what becomes of us when even the dead have little meaning? Perhaps that’s when the world finally and truly rots. Either way, I’d give anything to watch this godforsaken place burn to the ground.

RUPERTCROMWELL

December 2003

It’s early in the morning—the dim whisper of a bloodshot sunrise leaking through the closed shutters like dark red smoke—two days after Christmas when Rupert Cromwell’s father bursts into his bedroom and informs his son that “a backwards miracle has occurred.”

At first, Rupert thinks he’s dreaming.

His father never barges into his room, especially without the decency of knocking first.

Rupert stirs a little, pulling the bedsheets tighter and up over his head to block out some of the light leaking in from the hallway. But his father won’t relent. Instead, he leans closer to him with a desperation that Rupert can sense, like when his father is caught in a lie. His father repeats himself once more. But Rupert doesn’t answer. Instead, he’s lost and unbound somewhere in the enchanted realm of twilight that bewitches the alert and conscious.

In his dream-like stupor, Rupert wonders what he was imagining that was too difficult to part with when his father first interrupted. Perhaps he was dreaming of the Christmas muffins they enjoyed, lathered with butter. Maybe he was imagining the gifts he had asked for from his father that he knew wouldn’t appear beneath their tiny Christmas tree. Or perhaps, more likely, Rupert was dreaming of those magical Christmases he had spent with his mother, what now feels like eons ago—the hot chocolate they had warmed on the stove, the gingerbread homes they had gleefully built, the carols they had sung even though Rupert’s father wouldn’t join in the fun.

Although Rupert had tried to keep her spirit alive during the Christmas after she died, he knew he was incapable of completely resurrecting her delight, her liveliness, her essence. Now, several years after her passing, he doesn’t even bother to make the effort. Much of the Christmas he endured this year was spent reclining in bed, and nursing an awful head cold which seemed to poison him completely and rob him of his remaining hopefulness for a cheery holiday season.

He sniffles a little, clearing some of the snot from his nose and scowling when he tastes it in the back of his throat. Even with his eyes firmly closed, he can still feel his father’s presence lingering near the foot of the bed. He listens to the floorboards screech like newborn bluebirds while his father paces the small room, his weight shifting from one board to the next. He contemplates if his father were imagining the pleasure of prying up some of the wooden planks and cramming Rupert’s body beneath them.

Although he knows in his heart that his father would never intentionally hurt him, there’s a distrustful part of him that doesn’t know how to act around him. When they talk to one another, it feels as though they’re speaking different languages. Rupert hasn’t trusted anyone since his mother passed away three years ago. Although his father attempts to make an effort from time to time, Rupert has already closed away so many parts of himself to tenderness, sympathy, and affection. He’s been told he’s especially difficult for a seventeen-year-old boy, but he refuses to pay attention to any criticism considering all he’s endured in such a short time span.

Rupert wonders if his father is making some sort of gesture—some absurd, almost comical signal—to bond with him. Rupert can’t be too certain while he’s buried in blankets and drifting in and out of sleep. But he wonders if this surprise morning visit is some kind of new ritual for father and son. Even if it is a feeble attempt from his father to crawl further into Rupert’s mind, Rupert wants no part in the spectacle, especially before the arrival of daylight.

“Didn’t you hear me?” his father asks him, leaning close enough so that Rupert can taste the warmth, the rancor of his fetid breath. “Something’s happened…”

But what does Rupert care? He knows his Christmas has been wasted thanks to his sudden illness. While he’s on the mend, he’s still groggy and feverish. He hasn’t been eating much lately either. His father knows all of this. So, why does he insist on bothering me?

Before Rupert can grab the bedsheets and pull them tighter, his father snatches the blankets from him and hauls them off the bed until they’re crumpled in a heap on the floor. Rupert senses himself becoming more and more alert. For a moment, he stirs there, wondering if his father had really done that. His father is usually never so forceful, so unrestrained with him. There had been times when Rupert had imagined his father might have enjoyed the prospect of manhandling him so that Rupert would obey; however, it seems so ludicrous to happen now, after all these years. When Rupert realizes he’s not going back to sleep anytime soon, he shoots up from dozing and stares at his father, begging him for an answer.

“Quick,” his father says. “Get dressed.”

Rupert glances at the alarm clock on the nightstand. 5:34 a.m.

He groans, slamming himself against the mattress and rolling over on his side until he’s facing away.

“It’s not even six o’clock yet,” Rupert whines, his throat itching and burning. “I’m still sick.”

But his father’s already at the room’s threshold, flicking on the switch. Light floods the small bedroom and Rupert winces, shielding his eyes.

“Ten minutes,” his father says. “We’ll be late.”

“Late for what?” Rupert asks, straightening once more.

However, it’s no use. His father has already moved out of the room and is hurrying down the narrow corridor, summoned by some soundless whistle.

Rupert sits in silence for a while, going over the possible scenarios in his mind, wondering what he could possibly do or say to get out of this. It’s not that he doesn’t want to be around his father. He would at the very least be honest with himself and confess that truth if it were accurate. But it’s not. The truth is that Rupert plans to leave home when he turns eighteen and he doesn’t want to feel homesick for a place he never truly connected with anyway. He’s afraid of the surprise of a tender moment between father and son. He dreads the possibility of his father showing him that he’s kind and gentle and giving—all the things his beloved mother was before she died. How unfair would it be for Rupert and his father to become close and bonded just before Rupert finally left town?

He doesn’t want to indulge that thought. It upsets him too much. He’s keeping his father at a distance for the foreseeable future. Any attachment, any connection could make it difficult for him to move on. Just like the connection he felt for his mother. He has already spent the last three years undoing that particular invisible thread, and he’ll be damned before he allows another one to be fastened in its place.

With so much reluctance, Rupert slides off the bed and ambles toward the dresser situated in the corner of the room. He clears some of the phlegm in his throat—burning when he swallows—and he comes upon a small, framed photograph of him and his mother at the church rummage sale the summer before she passed away. In the photo, she’s kneeling in front of an old vehicle that looks like it belongs in a silent movie. Rupert is at her side, making a goofy face to the unseen photographer and pointing at the car’s headlights, which look like the eyes of some prehistoric insect.

As he gazes at the photo, he senses the firmer, more guarded parts of himself beginning to thaw. However, before his guard melts completely, he pushes the photograph behind some small bottles of cologne until it’s partially hidden. His mother’s face—her warm, inviting smile—obscured for now and ready to be admired again when he’s ready, when he’s feeling a little less vulnerable and prone to weepiness.

He certainly doesn’t want to cry today. Or any day, for that matter. He’s closed himself off for so long, he wonders if he’d even be able to cry if he wanted to. Rupert thinks of indulging in his misery for a moment, but he knows he can’t with his father waiting for him. He slips on a shirt and a pair of pants, sliding into black socks. His father never told him exactly how to dress or what to expect, so Rupert certainly hopes he doesn’t anticipate anything overly formal. His finger suddenly loops through a giant hole in the bottom hem of his shirt that he hasn’t noticed before. He sighs, realizing it’s probably time to buy some new clothes. Everything he owns is so tattered and worn—gifts from his mother so many years ago. He grimaces, wondering if throwing out the shirt she had once bought for him might be an insult to her memory.

When he’s finished dressing, he stares at himself in the floor-length mirror beside the door. He’s a little thinner than he’d like to be, the lines of his ribcage visible through the thinness of his skin when he poses a certain way. Some of the kids used to make fun of him at school for the crooked shape of his nose and how it curves like the beak of some bird, but they don’t comment much more on his appearance ever since his mother passed away. Rupert figures that his classmates concede he’s already suffered enough. He laughs, amused at the thought that even high schoolers are able to realize “enough is enough.”

He wishes he had less body hair. So much of the hair on his chest and underneath his arms is completely unmanageable and makes him feel like a wild animal. He’s tried to shave himself a few times, but the discomfort is not worth the price of momentarily accepting himself. Not to mention his hair seems to grow back darker and thicker than before, almost like his body were attempting to tell him that it’s been insulted, besmirched.

Sometimes he stands in front of the mirror for hours and picks apart his naked reflection—from the scrawniness of his arms to his spotty-looking face to the smallness of his genitals. He often wishes he were someone else. Moreover, he often wishes he were somewhere else.

Anywhere but here: the dreadful town of Burnt Sparrow.

* * *

Rupert hesitates slightly, slowing as he shrugs himself into a plain black T-shirt. He lifts his bedroom window, cold air blasting him in the face. It’s just then that Rupert comes to the peculiar realization that he can no longer smell the fetid stench of sulfur lingering in the air. He clears his nose with a tissue and smells the air once more. For the first time in what feels like an eternity, the scent is completely absent—those three-hundred-year-old contaminated spirits once dwelling at the abandoned town mill now completely and utterly gone. But to where?

The town of Burnt Sparrow has been clouded by the odor of sulfur for as long as he can remember. It seems so curious for the air not to hang heavy with that poisonous scent, not to churn with that loathsome, unbearable stink. He can’t recall a moment from his childhood when he didn’t have to plug his nose at the God-awful smell—the very scent of the town’s failure: a large paper factory that’s been abandoned for as long as he’s been alive.

He always thinks of his father whenever the town’s ancient paper factory creeps into his mind. He recalls how his father used to entertain him with gruesome tales of incidents he had witnessed while working at the factory before it finally closed. There was one story in particular that has always haunted Rupert—a story about one of the mill workers who had his arm seized and caught in one of the large printing machines. His father had told him how several line men rushed to the poor man’s rescue while he thrashed there, screeching until hoarse as his arm slid further and further into the mouth of the machine before his bone finally snapped apart. Rupert grimaces whenever he reflects on how his father described the miserable sight of the poor, wretched thing—his empty, tattered sleeve dangling there and leaking dark blood all over the concrete floor.

Burnt Sparrow seems to be a place where the awful and the inevitable occur—a dreadful, haunted place. Rupert often laments and wonders if his very presence has somehow upset the balance of the community throughout the time that he’s been a resident. His father is always so eager to remind him how the paper factory shuttered the very same week he was born. Rupert often wonders if the town has always been a dark, evil place, or if it’s rather the sum of its miserable inhabitants.

He questions if perhaps his father, too, recognizes the very same absent smell of sulfur. He wonders if his mother might have noticed the absent smell as well. She was always so quick to complain about the lingering stench of rot that surrounded the town. She often told Rupert tales of how the scent of sulfur lingered in Burnt Sparrow long before the mill was first built in the late 1800s. Although Rupert’s father openly detested it, his mother was always so keen to tell stories—to share folk tales that had been passed down through her family.

Rupert’s mother had told him time and time again that Rupert was a natural born storyteller. Rupert wanted to believe this. He had dabbled with writing at school and had written several short stories for class contests that he regrettably did not win. From time to time, Rupert thinks about sitting at the desk in his bedroom and forcing himself to write a story he’s been considering for quite some time—a tale about two people in love who continue to hurt one another again and again and again. He thinks of how he’d start the story—the careful way in which he’d construct the narrative. But inspiration never makes its presence known. He wants so desperately to honor his mother and tell a proper story, the way she often told him tales at bedtime. Rupert often worries he’s not been endowed with the gift of storytelling as his mother once was.

Regardless, his beloved mother was always assuring him that he possessed the natural gift of a venerated scribe like Faulkner or Beckett. In the few months following her demise, Rupert had tried to write. He tried to tell stories that he thought his mother might once have enjoyed. But nothing seemed possible. It was as though a spigot had been fastened shut inside his mind—a doorway, a kind of threshold that could never be crossed again.

Rupert knows everything about thresholds. Standing at them and not going anywhere, that is. He often feels as though he’s permanently fixed at a precipice, smelling the sweet scent of freedom drifting from elsewhere but never able to actually partake. If only he were brave enough to take that first step—to cross the line, to go across the boundary and make his way in the world. Regardless, the only thing that seems to matter in the present is the very noticeable absent smell of sulfur in the air. Where could it have gone? Is this an omen of things to come?

Rupert closes his bedroom window and makes his way over to the mirror near the closet door. He looks at himself in the reflection and thinks about how he’s never once and truly felt like a man.

He already knows there’s no music, no poetry in the male existence. Instead, it’s a sort of void, a terrible kind of vacuum. Although there are indisputably brief moments when manhood seems obtainable to him—fleeting instances when he notices his natural coarseness, his rawness—becoming the true definition of a man seems like some impossible act, an awkward magic trick or an excessive kind of performance art.

Rupert often feels out of place around other men, almost like they possess a certain skillset he’s never quite mastered, as though they speak an ancient language that he could never learn. Rupert frequently observes the way men are together and he tries to mimic what he sees. He admires the boorish way they address one another—their noticeable crassness, their indelicate way of presenting who they are like canines at some outdoor dog park. Not all men are like this. It’s a gross generalization to argue that all men possess the very same unrefined, improper manner of behavior.

However, it’s glaringly obvious that he does not fit in when he’s around them. Rupert makes every attempt to match their crudity, their unevenness. But he knows his attempts are always brittle and hollow. They are pathetic imitations of true manhood, almost like he is some alien species that could never possibly translate the complexities of human behavior. Rupert has wanted to tell this to his father. He yearns to tell him how he doesn’t ever feel like a man. But he knows that this kind of confession would destroy his poor father. It’s not worth the heartache.

Early in the morning, Rupert often stands naked in front of the bathroom mirror, and admires the curve of his erection when he’s fully hard. His penis feels heavy and firm when he holds it with his hand. Sometimes it feels like the only thing about his body that won’t break apart. His stomach is flat and hairy. His muscles are somewhat defined, even though he doesn’t exercise as much as he promised himself he would.

Rupert even tried growing facial hair at one point, wondering if it might make him feel more masculine, more permanently rooted in a brotherhood that undoubtedly exists only in his mind. To anyone passing him on the street, Rupert probably looks like a very commonplace and ordinary young boy—unremarkable in every way, but familiar all the same. There’s something he loathes about that kind of familiarity. Something that’s immediately distrustful when he recognizes it in other people. To a select few that truly comprehend, Rupert probably looks suspicious. He resembles something that appears almost like a man but is not quite altogether what he promises to be. Indeed, if someone thinks this when they pass him, they are correct. He is not a man. Not a boy. Nothing. Instead, he uncomfortably exists in some kind of liminal space between the two. He’s a horrible fraud—a replica of something he once saw in a black-and-white movie, a crude mimicry of all the supposedly most perfect elements of true manhood, a soulless impersonation.

* * *

After he’s finished dressing and whispering horrible things to himself in the mirror, Rupert moves out of his bedroom and creeps down the stairwell. Most of the house is still dark. The vague glimmer of dawn starting to break has already begun to bleed through the living room windows and fill the room with a muted glow like the light from a distant bonfire.

Rupert narrowly avoids tripping over some of his father’s clothing strewn across the floor and his mud-covered black boots piled near the bottom of the staircase. Rupert shudders slightly as he passes over takeout cartons and fully drained beer bottles. He’s always been embarrassed of his home, and, for that reason, he never invites friends over to his house. That means he must always be prepared with some legitimate excuse as to why his friends cannot come over, but thankfully the opportunities for such invitations are few and far between.

Rupert reaches the kitchen, where he finds his father seated at the table and struggling to pull on his boots. Rupert stares at him for a while, watching while he grunts and works his foot deeper and deeper into the leather boot. He flinches when his father’s eyes dart to him.

“Wear shoes you don’t care about getting dirty,” his father tells him.

What could those possibly be? Rupert wonders to himself.

He has different pairs of shoes for different occasions. But he doesn’t necessarily have a pair that he would mind if they got dirty. Perhaps he’s accompanying his father on some sort of job assignment. It’s been several months since his father has worked, and they’ve been living off rations and the benevolence of Rupert’s grandmother in Boston. But surely she must be growing weary of taking care of Rupert and his father. It must be a loathsome reminder for the poor old woman as well—to continually donate money to her deceased daughter’s husband. Rupert’s father has mentioned the possibility of her not returning his letters. However, like clockwork, she sends a check on the third of every month.

Thinking this might be some sort of work opportunity for his father, Rupert quiets some of his selfishness and tries to think of what’s best for both of them. He’ll find a way to make money once he leaves town and journeys to the closest city. However, his father is troubled in such a way that makes it almost impossible for him to hold down a proper job.

His father is a dedicated and diligent worker, but there’s something about him that employers seem to be repelled by. Whether it’s the rotted stench of grief shadowing him at all times, or whether it’s because he’s different, Rupert cannot be certain why his father struggles to keep a paying job. It’s surprising that he and his father were never closer, especially considering how unique the two of them are. Rupert supposes they’re unique in different ways and, therefore, unable to truly appreciate what the other is capable of offering.

After Rupert snatches an old, tattered pair of sneakers from beside the door leading to the laundry room, he slips them on and tells his father he’s ready to go. His father is already at the doorway, fishing inside his pocket for car keys and then swiping the flashlight from the nearby counter.

Rupert and his father make their way out to the green station wagon parked in the snow-covered driveway. Rupert burrows deeper inside his winter coat as soon as a cold gust of wind slams against him and nearly knocks the air from his lungs. His father orders him to grab the brush in the back seat and knock off the few inches of snowfall from the windshield and roof. Rupert does, his fingers freezing from the cold, and when he’s finished, he climbs into the car and sees his father struggle to slide the key into the ignition. The car thrums alive, the motor sputtering in almost exact harmony with Rupert’s coughs as he covers his mouth with a tissue.

As they peel out of the driveway and down the tree-flanked lane, Rupert wishes he knew where they’re headed. He’s never been asked by his father to accompany him on one of his job assignments. With the local schools being shut down for the holiday, Rupert wonders if the remainder of his winter vacation will be spent doing whatever menial job his father has acquired. He can’t be too upset at the thought of his father working. Rupert knows his father wants to provide for him. Moreover, he knows his father only feels complete when he’s been assigned some sort of task or commission. At the end of the day, his father merely wants a purpose. That’s why the last three years have been nearly insufferable with the both of them living in the same house—their purpose, the reason for their determination, had completely vanished.

Rupert thinks of saying something to his father.

But what to say?

There’s probably too much to say. But Rupert secretly wants none of it. Once he might have basked in the joy of getting to know his father and bonding in the way that all fathers and sons are supposed to; however, he no longer feels that intense desire to please his father, or even to get to know him. Things are going to end the way they’re going to end, he thinks to himself. Rupert has every intention of leaving the town of Burnt Sparrow once he turns eighteen, and doesn’t exactly have any plan of visiting his father. To him, his father is a wretched reminder of his mother—all that he has lost. Why should he make attempts to bond with him? He’s going to lose him eventually.

* * *

Drifting in and out of sleep as the car gently rocks him while they drive along, Rupert leans his head against the passenger window. The frosted glass feels cool against the side of his face. He listens to the thrum, thrum, thrum of the car’s engine while it sputters along, the road disappearing yard by yard in front of him. Sometimes he glances out the windshield and imagines the car devouring the road ahead, leaving nothing behind them but flickers of soot and ash. Everything in this town eats away at everything else. The road bends and curves, empty roadway stretching out with dim headlights pointed ahead to slice through the infinite canopy of darkness. He observes while trees flicker by, different houses he’s known for his entire existence flashing before him while his father seems to push his foot down harder on the accelerator. Why could he possibly be driving so recklessly? He’s filled with the delirium of a head cold, but even Rupert knows they’re driving too fast, too reckless for his own comfort. Where is he taking us?

Rupert’s attention is eventually pulled out of the passenger window, and he notices the abandoned ruins of the large paper factory perched on the nearby hill like the dark silhouette of a strange, otherworldly castle. It feels grotesque to witness the horrid thing sometimes. All the poor, wretched souls trapped there forever because that’s where they had perished while performing the toils of excruciating labor. Rupert feels a pang of pity for the poor things permanently imprisoned in the town of Burnt Sparrow—both the living and the dead. He can’t quite imagine the torment of the spirits who probably wander the factory late at night—those moth-eaten, threadbare souls aching to depart and then ultimately being met with refusal time and time again. Every place in this world is a kind of trap, whether you realize it or not. Very often, you’ll come to recognize the signs when it’s too late.

Rupert rubs his nose, wondering why on earth he can’t smell the familiar scent of the paper factory—the stench that’s haunted this town for years. It feels as though some gigantic cosmic vacuum has sucked up the foul odor and then left nothing in its place. He chuckles a little, amused at the thought of things being taken away from Burnt Sparrow bit by bit, day by day. A necessary penance for existing. A kind of natural atonement for the terrible sin of dwelling here and calling this awful place home. Rupert imagines some sort of invisible vampire draining the lifeblood from the town slowly but surely each day, without fail. There are some things in this world that only take and never give anything in return. As Rupert glances at the abandoned remnants of the paper factory three hundred yards or so from the main road, he wonders if he’s similar to a vampire, some sort of nocturnal ghoul yearning to feed, to consume others. He fully recognizes how he takes more than he’s given from time to time. He had done that to his mother. Whether she gave willingly or not was beside the point. Perhaps that’s why he’s uncomfortable around his father. Maybe it’s because his father knows that Rupert is eager to take things that don’t belong to him—a consumer, a being that feeds without reserve in order to survive.

As they continue to drive, Rupert thinks of how he ventured into the paper factory once when he was a few years younger. One of the kids in his class, a young boy named James Grott, had dared Rupert to spend thirty seconds inside the factory after dark. James and his cronies would time Rupert after he made the trek across the factory’s threshold—a large door that had previously been boarded shut but had been opened by vagrants and other kinds of trespassers. Rupert recalls how he stood at the threshold leading into the abandoned factory, the noxious odor of the sulfur passing through his very skin. He stood there, whistling slightly to calm some of his nerves and to provide some of the much-needed resolve to enter the area. Rupert had urged himself to take the first step across the entryway, but his feet would not obey. He remained frozen, unable to move. His stomach curls when he thinks about what he thought he saw in that darkness—the bent, snarled faces of those who had perished long ago, those who had reluctantly sacrificed themselves for the sake of industry. He idled at the threshold for minutes until James and his friends’ teasing became nearly unbearable. Rupert shudders a little, shifting uncomfortably in the passenger seat, when he thinks of how he recoiled from the threshold and then darted away from the factory until he could no longer hear the sounds of the other children cackling mercilessly at him—taunting him, jeering at him, shouting terrible names. He thinks back on that night with such shame, such disgrace for not crossing the threshold and not proving to them that he was worthy of being in their friend group. Instead, he was thought of as a coward. Rupert knows he cannot control the perceptions of others; however, it’s impossible to avoid being defined by them. Perhaps one day he will cross that threshold. Yes, one day he will easily issue those steps toward becoming a true man. But today is not that day.

Another ten minutes or so pass and Rupert makes the sudden realization that they’ve been driving toward town—the narrow lane ahead of them veering to the left and winding through a small thicket before they finally arrive at the entrance to Main Street. But for some strange reason, they can’t take Hatchet Street to the town center as they usually do. It’s been blocked off by local authorities, police cars idling in the center of the lane with their lights flashing red and blue.

“We can’t go that way?” Rupert asks his father.

But his father doesn’t answer. Instead, he grips the wheel a little tighter and merges with the lane that feeds into the roadway where the local church is located. They arrive at the church and park near the recreation hall. Rupert continually looks to his father for an explanation, but his father will not meet his gaze and divulge his secret, no matter what.

“Grab the flashlights in the back seat,” his father orders.

Rupert obeys without much prodding, snatching the flashlights before he and his father begin to move away from the church and toward Main Street. He feels as though he’s merely going through the motions, obeying without much thought. But Rupert doesn’t want to be a soulless thing, capable only of obeying his father’s every bizarre command. He feels a dull ache in the pit of his stomach—a hunger to be his own man, a desire to walk away from all this senselessness. But he cannot. He winces, feeling an invisible weight piled on him like it’s the giant finger of some deity hell-bent on keeping him stuck here. Everything in this world seems to want to prevent him from leaving Burnt Sparrow. I’ll probably die here before I have the chance to leave