Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Istros Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Catharine's tragectory in life is accompanied by failures in love, family traumas and an incredible romance with handsome Sinisa. The novel takes us through turbulent times in the Balkan region, from the eighties to the present day, portraying growing up in the twilight of communism, and giving intimate insights into all that happened to the region after that. Carefully crafted characters and masterful, dynamic storytelling place Catherine the Great and the Small in the company of the very best of novels , which speak about the reality of their geographic setting and are remembered for their convincing, strong, maladjusted characters. Catherine is certainly one of them: a powerful female voice seeking her place within her family, among friends, in the cities she lives in, and constructing her unique identity as a daughter, granddaughter, friend, mistress, wife and a mother. 'The splendid language of this novel is skilfully and vividly translated, and the narrative is compelling. What is also striking is the portrayal of the characters with all their flaws and foibles (and who gain our sympathy perhaps particularly because of them). This inclusiveness of vision towards both characters and places – without judgement, rejecting nothing – is a special quality. It is the viewpoint of our greatest organ of perception, the heart, a territory that Olja Knežević knows well and has made her own.' Morelle Smith, Scottish Review 'This is not a they lived happily ever after novel, not least because they lived happily ever after all too often does not happen in the real world. Catherine struggles, she falls, she fails, she picks herself up, she carries on, for herself and those she loves, and, somehow, she does not get the perfect situation but makes an accommodation with those around her, keeps her head help up high and marches on. We can only wish her well.' The Modern Novel

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 388

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

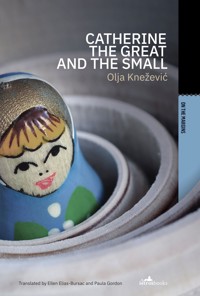

Olja KneževićCatherine the Great and the Small

Impressum

BOOK SERIESNA MARGINI / ON THE MARGINS

book no. 11

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Drago Glamuzina

MANAGING EDITOR: Sandra Ukalović

Olja Knežević Catherine the Great and the Small

PUBLISHER: V.B.Z. d.o.o., Zagreb 10010 Zagreb, Dračevička 12 tel: +385 (0)1 6235 419, faks: +385 (0)1 6235 418 e-mail: [email protected]

FOR CO-PUBLISHER: Istros Books Conway Hall, 25 Red Lion Square, London, WC1R 4RL e-mail: [email protected]

FOR PUBLISHER: Mladen Zatezalo

EDITOR: Susan Curtis

PROOFREADER: Charles Phillips

GRAPHIC EDITOR: Siniša Kovačić

LAYOUT: V.B.Z. studio, Zagreb

PRINTED BY: Znanje d.o.o., Zagreb May 2020

E-BOOK: Bulaja naklada, Zagreb

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

ORIGINAL TITLEMarina Šur Puhlovski Katarina, Velika i Mala

Copyright © 2019 by Olja Knežević and V.B.Z. d.o.o.

Translation © 2020 for UK edition Paula Gordon and Ellen Elias-Bursać

copyright © 2020 for English edition: V.B.Z. d.o.o., Zagreb

This book has been published with support from the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Croatia.

ISBN: 978-1-908236-40-1 (print) ISBN: 978-953-52-0320-9 (ePub) ISBN: 978-953-52-0323-0 (mobi)

Olja Knežević

Catherine the Great and the Small

Translated by:Paula Gordon andEllen Elias-Bursać

I am Catherine the Great, hiding away in a small room.

We have proclaimed this small room an office. English people call a room of this size a broom closet. The English people are spoiled, or so my husband and I say, even when they’re poor. That’s our attitude all year long right up to Christmas, when the bitter cold sets in. Then we marvel at them running around town in the howling wind, going about their business as usual, bald men without hats, women wearing ballet flats without socks, everyone sleeveless, and again we remember where we’ve come from: a small Mediterranean country where as soon as the north wind blows, no one goes outside, where everyone leaves work early – noon at the latest – with the excuse of attending funerals and paying respects.

The small room has become a workroom.

My husband says we should build a new life out of the contradictions of our personal origins and mindsets. We shouldn’t be layabouts or crybabies. I agree, even though I have begun to hold plates as if they were butterfly wings, pinched between my thumb and two fingers. Every weekend, at least one slips from my fingertips, numb from poor circulation, and shatters. Weekends are an accumulation of separations, the lowest point of concentration, early evenings unmoored in strange cities much colder than I’m used to. At those moments, my thoughts turn to home – yes, I even say home, sweet home to myself – and I miss everything and everyone, but most of all, my grandmother. When I lived with her, she didn’t let me help her with work around the house. I never got the hang of it, though I haven’t done any other type of work in this city for a long time. Granny bubbles up to the surface more and more often: When, for instance, from out of my dressing-gown pocket I pull a half-wrapped, linty butterscotch or an accidentally washed, disintegrating banknote to shove into the hands of my children while they grimace and complain, because really, they didn’t mean that when they said they wanted a sweet or asked for spending money. I hear Granny speaking when, instead of quarrelling, I take a deep breath and let out a sharp: Mm hmm, miscreant. And here she is at the end of the day, taking my left hand and using it to pull the duvet up over my hips, up to my shoulders, covering me so that my kidneys don’t fall off from the cold overnight, as she used to say instead of good night. But these days I call her only on her birthday and the most important holidays, New Year’s Day and May Day.

Today I didn’t sweep up the bits of broken plate from the floor of the kitchen in our fifth apartment in a foreign country. Terrazzo moderno, the estate agent said as she opened the door to the kitchen during the tour of the flat. She pronounced the letters T, R and O the English way. I pretended to be in control of everything happening to me and imagined that I, if I’d had the choice, would have picked those very same terrazzo moderno tiles. Three bedrooms and a living room, plus this workroom set at the far end of an angular hallway. On the tenth floor, with the immensity of the metropolis all around us. Life has never promised anything to anyone, all of this is a gift from heaven and I am grateful, even if my only anchor is a rickety table painted the colour of yellow sponge cake. Hunched over this table, I write for myself and myself alone, much to the amusement of my household. “An extravagant hobby, that’s for sure,” they say, and they chuckle. Writing one’s memoirs, a hobby worthy of an empress, of Catherine the Great. None of them will be sweeping up the bits of broken plate.

In this city of dreams, I’m not seeking adventure, I’m not on the lookout for a soulmate.

CATHERINE THE SMALL

1.

It’s the beginning of summer, 1978. Grown-ups tell us we are the lucky generation, we should be disgusted by revenge and butchery, we should break the cycle. And they teach us: When they throw stones at you, throw bread to them. Good old Communism, we agree after a huddle in front of the building, to answer stones with bread − the finest social system in the world. We had never read the Bible. It was not available to us, and besides, word got around that it was boring, and Marietta, who would know, confirmed it. “An old book for old people,” she said. Her father was an army man, but her mother was from Pula, in the Republic of Croatia, and kept a Bible hidden under Marietta’s winter clothes.

It’s the beginning of summer and only the most experienced guerrillas, like me, hide from the gendarmes in the smelly alley next to the burek shop. We press up against the piss-stained wall, keep quiet and breathe into our cupped hands; in the heat, the smell of ground meat and onions hangs thickly around us, a smell that keeps our enemies at bay. Grown-ups we don’t like, grown-ups like Marietta’s father, try to convince us that the shop owner fills his burek pies with ground-up cats.

No, we don’t say gendarme like they do in France, we pronounce the g like the dg in fridge. Guerillas and gendarmes. We all call the game “cops and robbers” in front of the grown-ups. They ask us if it’s where we hang out with friends or somewhere else that we heard people singing rabble-rousing World War II Chetnik songs. My grandmother asks me this, she’s who I’m most scared of, and that’s why I hide the word gendarme from her, it sounds like Chetnik to me. I don’t know what songs she means − I listen to Boney M and practice dance moves with three of my girlfriends. Ra-Ra-Raspuchin, lava-rava-wash-machine is how we sing it all wrong.

I am in love with one of the gendarmes. I want it to be him who finds me in the eternal gloom of the alley by the burek shop. If he finds me, if he approaches me from behind, so I have to turn around suddenly to face him, I’ll kiss him on the lips. Who cares that I’m so skinny and have a bad haircut? I know how to kiss; my pillow can vouch for it. I use everything I have: my lips, teeth, tongue, hands, hips and breath − and when imagining myself in the act, my whole body trembles from the force of imagination.

It’s June, school’s just broken up, and the dirt is already cracked from the heat, resembling chunks of aged cheese from the farmers’ market. We tasted this dirt, literally. As little kids, when we were hungry, we tried chewing the dry earth that looked like cheese to us, we all did, and now we laugh about it. In the early afternoon, the smell of dirt mingles with the smell of rubbish from the plastic bags tossed near the building entrances, with the smell of petrol from overheated cars, along with the smell of musty pink and white oleander blossoms. That’s when we go inside for lunch. Things simmer down in the evenings, even the oleander has a delicate smell then, and we tell each other the fragrance is a trick − the white flower is probably poisonous. But we still lick the blossoms, and we lick the leaves, defying destiny under the heavens chock-full of big, fat stars, which watch us from above, follow us, are astonished by us and love us, as do our mothers watching from their balconies across the neighbourhood.

Well, other mothers, anyway. My mother is ill, she’s in the hospital. I’m the only one of my friends in this situation. Enisa told me this makes me unusual, but it actually means I always feel sick to my stomach, and maybe a little ashamed. I like it better when my mother’s home, even if I hear her moaning and throwing up, because she’s a fountain of life in my little family. Without her help, my hair doesn’t look like it’s been intentionally cut in a punk hairstyle, it just looks mangy. Mum’s hands are a greenish yellow, and so are her feet, which I am not supposed to see, but I always look at them before she slides them into her slippers because she wants to sit, she tells us, and not lie down while Dad and I are in her room. She wears a lot of make-up and she wears a wig when she expects us to visit. All around her are lavender-coloured bottles of Yardley deodorant, which she sprays on herself and her squeaky hospital mattress to try to cover up the complex stench of her illness.

“It’s good, I always recognize those cheerful footsteps of yours,” she tells me, “so I pull myself together quickly. I’ll need a new bottle of Yardley.” She gives me a scrap of graph paper. “Here’s a list of things to buy for me.” The list is illegible, just scribbles on paper, lines that scare me, arrows pointed at my eyes. Dad stands behind me, he sees that the paper doesn’t have any real words on it, and he squeezes my shoulder with his beefy hand, a sign that I shouldn’t say anything about it.

“But aren’t you coming home soon?” I ask her. “The May Day Festival is coming up. We’re practising a dance number to a Boney M song. I’m the man in the group. I took your white hat and Aunt Mela adapted Dad’s white summer trousers to fit me perfectly.”

Mum waves the thought away with her greenish-yellow hand. “I am so sorry,” she says, “I don’t think I’ll be out of the hospital by then. Ask Mela to give you an Afro-style cap A hairdo before the performance, she knows how. And well done on your part.”

“Only Marto from the green building knows how to do those moves. He taught me. His father won’t let him perform with us.”

My father laughs at that, and Mum hugs me and wants me to sit next to her. She’s so happy that I haven’t turned into the child of a sick mother, she tells my father. “We have made a special young lady of her, a strong girl,” she adds and kisses me. She doesn’t know that I am repulsed by her hospital bed, the room full of needles and tubes, the rolls of gauze and cotton batting flecked with pus and blood; my nostrils are filled with the sharp smells of the medical border-zone between life and death.

I didn’t know I was losing my mother forever; they failed to explain this to me. That summer I caught only snatches of information that directly affected me. I’d ask if she would still be in the hospital when I packed for my seaside summer camp, because if she would, I’d leave behind the ugly black crocheted button-down granny jumper, the one with the bat sleeves, which my mother said made it a “hippy jumper”, perfect for summer evenings. It took me a long time to forgive myself for those hospital visits, during which I sulked, bragged and kissed her only when she insisted because I was off to a rehearsal or to play outside. For her sake, I had to get through seventh grade with excellent marks. Father had told me the year before, adding “Maybe she won’t make it to your middle-school graduation,” while he fished a cigarette out of the red-and-white pack in his shirt pocket, lit it, and stared into the distance. Explain to me, I wanted to yell, what exactly does that “maybe” mean? What are the odds, I wanted to know. Mum was so young − the youngest and most fun-loving mum of all my friends’ mums. Can’t she just break free from this horrible disease and run away? How did she even end up sharing a hospital room with old women, some of whom even get to go home again because they only have pneumonia?

“Cancer, damn it, cancer,” I heard my father say to someone over the phone. And then: “I don’t know any more what part of her isn’t affected.” Not sure how to behave, he started acting the part of the gloomy Byronesque hero, brooding about life, and especially death, while my mother languished; he tried to find some sense in it, but he only became more and more isolated in his personal bastion of knowledge, at the philosophy department of the Nikšić Teacher Training College.

And now here I am at the end of eighth grade. My father, having quit smoking in the meantime, is fit as a fiddle. He uses expensive lotions on his face and is about to have a son with another woman. Still young, with a black moustache − which he grew out to cover his soft upper lip and laugh lines and look stern.

Before Mum ended up in the hospital, Dad often brought students home with him; they sat in the living room and smoked freely, copied out underlined passages from Dad’s mimeographed handouts; Mum would offer them something to eat, but they only wanted coffee. They talked to me about music. “You’re fierce with that punk hairdo,” they told me, “you’re way above kids your age.” I took it to mean they thought I was on their level, and I beamed − how great was that?

“A little Patti Smith,” said one student.

Philosophy lovers were rare, practically illegal. Communism was the crown of all philosophies. And I wanted to be like someone called Patti Smith and live in the Chelsea Hotel in New York. Fierce indeed.

My mother, who took me to parks and sneaked with me into other people’s gardens to steal bulbs, who taught me to draw all sorts of flowers and trees, would, all too soon, get so weak that her hand made jagged and broken lines on paper. She wasn’t even able to write down an ordinary list and wouldn’t live to the age when one learns to sit still and enjoy gazing at the violets.

My mother didn’t live to the age I am now, not even close, but already she was, as fate decreed, old enough to die. The illness advanced quickly, but Mum continued to wear make-up − a lot of it, like other young women did at the time. She wore a wig as if she were in a play, and she insisted on sitting with us, not lying down, when we came to visit, because she wanted to be closer to us, she said, she wanted to feel our energy, which she’d been a part of, too, until just recently, until she became weak and out of breath, as if she had climbed up to meet us from the depths of the earth, and then sat on the very edge of her own grave.

Mummy, I wanted to tell her, nobody likes me, fix my hair. Look at it, it’s awful, all the old people think I’m a boy: “Hey, son, go on, get me some smokes and a newspaper?” “I’m a girl!” I always correct them, but they just shrug. “I don’t have any coins. Keep the change.”

We all wore cotton T-shirts and jeans. The shirts and the jeans had Levi’s tags on them, like we were in the West. That, we heard, was something kids in the Soviet Union couldn’t even dream of. Over there, with these things, and with chewing gum, you could buy a house with what they were worth in rubles − but who’d want to live in the USSR? We got the shivers thinking about the enormous expanse to the east, where the dark would swallow you in the blink of an eye. Gulag, gulag, we whispered, imagining a goulash made of human flesh. Our social system is completely different, we said, parroting the grown-ups. We would rather live in Bari, or anywhere in Italy, if not London or New York − even Pula, where Marietta’s mother was from. That girl Marietta was the best at French skipping: she had skinny legs, sick skinny, we said, and she whistled through the air on those legs, decisive, precise, but gentle − swish, swish − she could jump over the elastic even when it was around our necks, and the elastic never broke skin or drew blood. I can still hear her mother calling her at noon from the balcony to come home for lunch, which astonished us because we had just eaten breakfast. And she ran fast. Her father, one of the nameless fathers who will forever be only “army men”, used a stopwatch to time her at a hundred meters and announced the results out loud: “Twelve-point-zerooo-five, we’re getting faster. We’re right behind you, Little Miss Šteker, guard your medals!” “Who’s Miss Šteker?” we asked. “Martina Šteker, record-holder for the one hundred metres,” Marietta answered. “I bet she gets the hiccups every day when my dad says her name.”

That June she said they were moving back to Pula. She showed us pictures of the lit-up Roman amphitheatre; talked about the film festival, how all the actresses went around topless, and no one laid a hand on them or even said a word.

***

I’m alone in the building entrance. All the guerrillas have been found except me. I’m tired of hiding; I move my skinny body away from the piss-stained wall. I decide to turn myself in, sad because I think no one wants to find me, that is, “capture” me, the way they “capture” the other girls, showing they like them by grabbing their breasts or bottoms. I don’t yet have those fleshy features. A man’s shadow fills the doorway. I hold my breath. Is this the maniac from our part of town, the paedophile who loves boys? Maybe he’s been stalking me, thinking I’m a boy.

“Kaća?” Phew. Someone who knows me well enough to use a nickname, the voice of one of my cousins.

“I’m hiding, leave me alone,” I say.

“Kaća, come home with me. Your dad’s waiting.”

“What’s going on?”

“Why do you always ask so many questions? Don’t be a pest.”

He’s not yelling, which is unusual, considering he has the personality of a nervous teenager. His nickname is even Jumpy Two. Jumpy One died young, he was killed, driving too fast, trying to break the neighbourhood speed record to the coast, to impress a girl known as Flamenca, who soon after that got married and disappeared.

“Hey, just come with me,” says my cousin, Jumpy Two.

Outside the building entrance I see everybody, the guerrillas and the gendarmes. They’re standing there, heads bowed.

“Kaća,” says the boy I’m in love with and whom I’d been planning to kiss impetuously. He comes up and hugs me. “I’m really sorry,” he whispers. Oh, the all-encompassing warmth of his embrace. My skin tingles from the heat.

“What are you sorry about?”

We look at each other, he’s uncomfortable. He takes a deep breath: “Y-your mother died,” he says, and kisses me on the cheek. The kiss makes me happy. A brief moment of happiness before a long stretch of grief.

Nah, Mum’s just really ill, maybe she passed out from the pain, she can’t have died-died, I tell myself as I enter our flat. The cousins are there, and neighbours, and Marietta’s mother, who is clutching to her breast her famous Bible, which I stare at for a very long time. This is not a good sign, I conclude, but still − one good sign is my dour granny clucking her tongue in the hallway at my mother’s choice of wallpaper, patterned like fireworks.

“Who wouldn’t get sick from this wallpaper?” she asks under her breath. She’s my mother’s mother − surely the wallpaper wouldn’t matter so much to her if her youngest daughter had actually died-died?

My cousins kiss me, wipe their cheeks with one hand and mine with the other. At least four sandpapery palms brush my face and I have not even begun to cry. My ill-tempered granny and I are the only ones not crying.

“Your mother died in the hospital,” they tell me.

“Your father looked for you,” they say, “he waited for you but he had to go to the hospital without you.”

“I told him to go without you,” Granny says crossly. “Enough of dragging you around hospitals.”

“Alone in a hospital room, such a shame.” They all sigh.

Dad and I are supposed to feel a little shame. At that time, people died in their own beds. But this husband hadn’t even considered bringing his young wife home. And look at me! I was making a fool of myself, twitching and wiggling around on stage at the May Day Festival, imitating a black singer no less, while my mother succumbed to a fatal disease.

“Don’t worry,” they console me and stroke my bristly hair. “She had no idea she was alone, that’s what the doctors said.”

“She’s blessed now in the kingdom of heaven,” says Marietta’s mother and smiles through her tears. “And you, child, just let the dead bury the dead.”

“All of you are babbling,” says Granny, agitated. “No one knows a thing. The doctors don’t know and neither do the messengers from the kingdom of heaven. Everyone’s guessing. How could we possibly know if a person is conscious or not as they’re dying?” Then she mutters, as if to herself, “I sure hope I’ll be conscious. But it looks like everyone else would rather be permanently unconscious, which they are.”

“Eat something,” one of Dad’s aunts from Titograd tells me, while another turns her attention to Granny: “I brought you breaded eggplant.” The dining-room table is groaning under all the food.

“These people think only of gorging themselves,” mutters Granny. “A hungry stomach has no ears.”

“Is she really dead?” I ask.

They tell me she is.

“For good?”

For good.

“She’s gone to her rest,” Granny tells me. “She was in a lot of pain. You’re in shock now, but thank goodness at least someone here has their wits about them.” I know Granny means herself. She goes on to say that her neighbour, Čeda, had warned her in time. Čeda ran over earlier to tell Granny that when she poured her morning coffee, the grounds overflowed the demitasse right on the female side, leaving a sickly brown trail, from the cup to the saucer, headlong, no stopping, not even when she moved the cup to a newspaper to soak it up. “There you have it. Your mother couldn’t bear living any longer. Who can bear living when cancer takes over your brain?”

She went to her rest. The others repeat this; realizing this phrase is the wisest possible thing to say. I prefer what Marietta’s mother said to me, as if imparting a secret: Let the dead bury the dead.

Until then death had been part of the fairy tales I read, where mothers die at the beginning of the story, and nothing is explained. Then the stepmother enters the life of the heroine, and no words are wasted on the death of the mother. The mother dies in childbirth and that’s that, on with the story.

2.

The only thing I remember about my mother’s funeral is me staring into space and pinching myself on the arm, thinking, I am alive. I am alive. Let the dead bury the dead.

I began spending time in my mother’s wardrobe, smelling her and touching her through her “rags”, as she called them. Out of doors, I saw mirages, my mother in one of her long skirts, “My Gypsy skirts,” she used to say, with approval, because she loved herself in the role of a Gypsy woman, a fortune-teller, a hippy chick, an artist − not just an art teacher with colourful bracelets up to her elbows and earrings down to her shoulders. Sometimes I’d see a woman resembling her walk across the bridge with a protective aura of eternal spring surrounding her, magically swinging her hips down the boulevard. Mum! Mummy! A surge of joy in my throat; my legs would carry me like a frightened deer, faster and faster, a sprint Marietta’s father would have gladly timed with a stopwatch. On the other side of the street, I’d be pierced by a sharp, deep pain, because never, never ever, never anywhere in the world, ever again, would this be my mother. My mother had simply disappeared, but before disappearing, she had not sent me a message, she had not written anything to me in a beautiful letter that I could carry with me always. I was literally left a motherless child. At those moments I’d stop, frozen in place, one minute, two minutes, as if in momentary death, and when I came to, I’d be in a crouch, doubled over with painful cramps. Neither forwards nor backwards. I’d wait, crouching, until the leaden sadness in my stomach passed, and then turn around, go home. Dad would be in the kitchen, cutting a loaf of bread down the middle, stuffing it with onions and ćevap meatballs. His paunch was growing larger by the day. We didn’t talk, except once in a while he’d ask me if I needed money for burek, yoghurt, ice cream. I’d wordlessly take as much as he slid across the table, then go into my mother’s wardrobe, among her skirts, tops and brightly coloured jumpers, and sleep.

One day, while I was outside, my grandmother came over and emptied out the wardrobe. Dad told me later that she wanted us to do it together, but she couldn’t find me, and he couldn’t tell her where I was, because how should he know where I wander off to when I sneak out of the house. Like it’s easy for him, a man in the prime of life left alone with a girl going through puberty. He didn’t look at me when he spoke. He tore a warm loaf of bread into chunks and shoved ćevaps into them. Out I went again.

I decided to walk around town using only passageways and streets where I couldn’t possibly meet anyone who could remind me of her, or anyone who could − with a look, question or recollection − confirm that she was dead. I disappeared into the dark cul-de-sacs of other neighbourhoods, into unfamiliar shops there, bought beer and cigarettes. Maybe, in some kind of miracle, Mum would come looking for me, to shout at me for my bad behaviour.

But instead of my mum, my granny came looking for me. One of her spies alerted her that he had seen me, roaming alone in a field, near the shacks. Granny quickly hunted me down and moved me into her place. She let me smoke a little and drink beer with her, as long as I regularly did my homework and kept up with my reading.

***

“My stomach hurts,” I said one evening to Siniša, the gendarme I was in love with. “It hurts,” I moaned, just before the tears welled up and streamed down my face. I crouched, head down. And my nose was running, my throat was filling up with gobs of phlegm. Siniša crouched down next to me.

“Here’s a bench,” he said, “come sit with me.”

On the bench, he hugged me. That’s what I was waiting for. I think that before I fell in love with him, I fell in love with the way he hugged. I held my head in my hands, hunched over, with the hope that my sojourn in Siniša’s embrace would last long enough so that it could be considered the beginning of us being boyfriend-girlfriend. He asked if it was really my stomach that hurt, might it be my appendix? I wanted to say so many things, I even considered lying that it was my period, but I only managed, quietly, through sobs, to call for my mother, my face buried in his jumper. Siniša never wore a jacket because he was always coming from some kind of sports training or practice.

In the distance: explosions of firecrackers left over from New Year’s Eve, the smell of smoke, burning wood and tyres, and a winter fog. Up close: Siniša comforting me, holding me tightly but at the same time giving me room to breathe, to sob, to snuggle into his chest, into his jumper, which smelled like lavender-scented fabric softener. He kissed the top of my head, my barbed, prickly crown. I wiped my tears and my nose, and lifted my head. We kissed on the lips. And we kissed some more, hungry, like young, skinny wolves protected from the winter cold only by the warmth of the breath they exchanged. Lips chapped and dry, but kisses warm, wet and sweet.

“You kiss well,” he said. “Have you had a boyfriend already?”

“Yes,” I lied. “An older guy, he’s in ninth grade.”

“Opa!” he said. “Does he smoke?”

“Umm, yes, he does. Why do you ask?”

“His cigarette smoke wore off on you.”

“Ah, yeah, that’s really a problem. It’s why I broke up with him.”

“When?”

“Today. Before I came out tonight. He’s from downtown. He smokes and drinks beer, the idiot. He’s not into sport like you.”

***

Siniša, my first love, in the years of reading Maria Jurić Zagorka’s romances and Agatha Christie’s mysteries. Siniša was like Zagorka’s Siniša, exactly the same sort of Siniša: kind, compassionate, just and strong, at least at night, in my bed, at Granny’s, or at Dad’s house, when all I could think of was him, my avenging knight, lying on top of me, warming me with his body, protecting me and kissing me passionately. But the everyday Siniša, this one from our valley, from our neighbourhood, already preferred curves, went out with girls from the upper grades, from other schools, and only occasionally with me, and only before nine o’clock at night, when he fell into the sleep of a young athlete, while I, sleepless until the predawn hours, was racked by the fever of too many contradictory emotions for a girl of so few years.

Siniša was talented at all sports, those played with a ball and without one, in teams and solo. Fast legs and a quick mind, he had God-given talent for it all. I sound like my granny. She would have said something similar about Siniša, and then, lacking a wooden table, would have rapped her forehead. Women of all ages adored him. “An athlete and an excellent student,” they said. He decided to pursue football, even though basketball was his favourite sport. All of us loved basketball then − we considered it the game for clever people. Actually, Siniša’s father decided for him. He said, “Football, centre forward, so you won’t be a loser for the rest of your life.” I went to the stadium to watch his team practice. He waved at me from the field, with both hands, with a smile that could stop the entire city in its tracks. His mother and father turned around to see who their son was waving to. Mojca, Siniša’s mother, winked at me cheerfully, but his father glowered. And then they looked at each other venomously, long and hard, the two of them, I saw it − my seat was behind and above them in the stands − I saw them in profile, their mutual hate hissing from one to the other. Siniša, thank goodness, took after his mother. She had the lovely profile of a quasi-foreigner because she was from Slovenia: same country, different republic. When practice ended, Siniša came over to me first. We stood and chatted, exchanging pleasantries, which attracted attention, because our youthful desire to kiss each other right then and there blazed openly between us as we spoke. We chatted until Siniša’s father came up and pushed him, kicked him from behind, foot in the bum. Siniša staggered and I jumped to support him. Mr. Aco, his father, started to laugh the laugh of an old devil. His breath smelled like beer. The man always wore a giant pair of binoculars around his neck on a black leather strap, which made him even more frightening, like he was looking at us all under a microscope. Siniša dropped his eyes and blushed.

“You’ll never be a champ if you can’t take a little horse play,” his father said.

My heart ached. Siniša turned and walked away from us, quickening his step. Mr. Aco called to him, but Siniša didn’t respond. His father then grabbed me by the shoulder and shook me, not too hard − I felt more assaulted by his beer breath − all the while telling me with his sticky lips that his son had a bright future and he shouldn’t slack off at school. I understood that he thought I was a threat, but I didn’t understand why.

“They say Tito will come back to Titograd,” Mr. Aco said with a wink, “despite the lies going around that he’s ill. Siniša should be one of the model Pioneer Scouts standing in front of the Yugoslav National Army building to welcome Tito and his wife, Jovanka. An example for others, you understand?” He sprayed spit as he talked. He looked at my hair in disgust. Then he slowly lowered his gaze to my neck. I was wearing a thin silver chain with a pendant, the letter S.

“Is that S for Siniša?” he asked.

“No, it’s for my mother. Her name was Sanja.”

“I know, I know, I’m pulling your leg, don’t be frightened. I know who’s who. I know your granny as well as that aunt of yours who ran away from your granny to America. I went out with her for a while. She was a nutcase, but what a stunner.”

3.

“Your Sanja was a legend,” Milica said, and handed me two more mandarins from the crate next to her bed. “Of course she died young, like all legends do. Boring mothers and fathers outlive their own children. Look at my mother’s sole purpose in life: to create a nest egg for a rainy day. Crates of mandarins, dismembered animals in freezers. I heard that in Sanja’s art classes kids could talk about anything. About love, relationships, marriage, films, poetry. You’re a class act, wearing that S around your neck.”

Milica’s Nordic blonde hair, long like a mermaid’s, spilled over the bed, over me, and from the bed onto the floor. Mixed up in her hair were mandarin peels and shavings from sharpening her black eyeliners. She didn’t try to shake any of it out of her hair when she went outside, and she rarely washed it. She assured me that the smells of these scraps and oils kept lice away.

The kids from the building called her the blonde angel. She called them rejects and wanted no part of them. She was in love with the movies, with actors, Brando, Belmondo, Delon; with the freckled, uncompromising Katharine Hepburn; with the character actress Anna Magnani and her nose hairs; with the slightly cross-eyed Monica Vitti. “I feel like I belong in that world,” she told me shamelessly. She told everyone to their faces, shamelessly, that what she wanted from life was art, passion and freedom.

“Ciao, I’m Milica, I was born in an alternate universe.” That’s how she introduced herself in our class directory.

I lapped up every word. Her manner of speaking was glamorous and rich like Hollywood, a place she really did belong to. She memorized the women’s monologues from all the books she read. At thirteen she was already seriously preparing for auditions to get into the Belgrade Academy of Dramatic Arts.

“One may enrol at sixteen years of age,” she said, with impeccable diction.

“You need a C, too,” she told me, “for your fabulous name, Catherine. And right after Catherine must come The Great. You must grow up to be five foot ten. You have to be great like a fortress. Shoulders like a man and great big tits.”

“Do I have B.O.?” I asked her. “Are my arms too hairy?”

“You are perfect,” she assured me. “Siniša is afraid of that, as are all the boys. Show me your tits, Catherine the Great, I do believe they’ve grown.” She didn’t wait for me to pull up my shirt before pulling up her own. “Look. Mine are already sagging.”

They were not sagging, of course. She just wanted to show me her firm round breasts again.

“You have nicer nipples,” she said and brushed her fingers over mine.

“Lesbos!” All at once, her little brother, Radoš, jumped out from where he was hiding behind Milica’s curtains. “I’ll tell your mothers you’re feeling each other up and kissing on the lips.”

“Shame on you,” Milica said to him. “Kati doesn’t have a mother. Imagine what it would be like if we didn’t have a mother.”

Radoš’s chin trembled, his nostrils flared and he tried hard not to cry.

“Don’t, Mici, don’t tease him,” I said.

But she kept going. “What a crappy life that would be, eh? And on top of that some idiot, someone like you now, comes along to accuse you and judge you.”

Radoš couldn’t hold back his tears. He was already sobbing.

“Your crying means nothing to us, except that you feel sorry for yourself. Apologize to Katarina. When she becomes Catherine the Great, she’ll chop off your head.”

I consoled Radoš and told him he hadn’t hurt my feelings.

“Good riddance to bad rubbish,” said Milica, and turned my attention to our long-term goals. “One way or another, we’re going to ditch this backwoods town. You and me, kid. You can do anything, remember that. This place will stunt your brain. And I don’t intend to live my life with half a brain.”

She told me I had the strength of the earth, which, with its amazing ingredients, nourishes the cosmic mother, and that’s where I got my tranquillity from. She said she was the lesser being, who constantly feeds off aggressively strutting her stuff in front of an audience. The way she said it, I understood “lesser being” and “aggressively strutting her stuff” as compliments in the eyes of someone who possessed precisely those characteristics, and I happily became her audience. Her flame turned all my cramps and sorrows into ashes, into her room even the sun entered as if it were visiting an equal, to watch her as she rehearsed a monologue. She was the factory worker from Titeks who stole a sewing machine, becoming Mother Courage; she was the Balkan Antigone; Stella Kowalski and Blanche DuBois rolled into in one − “Every woman is split, my original thesis,” she’d say, “starting with my own mother. Tennessee Williams knew that and split one female character in two; he wrote them as sisters so the play would be understandable to a wider public. The wider public prefers their stories cut down to size for them.”

Milica had a photographic memory and an ambitious streak that was “inappropriate for an individual in our social system”, as her father put it, and she imitated him to a Tee. She had ambitions for me, too: she told me I’d write roles for her, the way I wrote letters to magazine advice columns. She bought popular women’s magazines like Couples, Bazar and Practical Housewife, and created comedies from them. “Come on, let’s rehearse a comedy from this pulp,” she’d say. Then I would put together an imagined reader’s letter, which she would act out.

“Believe me,” she said, “all those letters are made up, but you know why they’ll never publish your made-up letter? Your letters scare them. They publish only these wimpy ones, where the women are unhappy and pining for a man all day long, because if women don’t suffer and don’t pine, then they’ll soon become stronger than men, which is out of the question.”

I believed her, of course. And every day I suffered and pined for Siniša less and less.

Milica’s mother − Aunt Ceca, as we called her − worked at Jugo Export, “a fashion establishment of the highest standard”, she said. She kept fur coats in an armoire in Milica’s bedroom. It looked like they were part of her nest egg for a rainy day. She always had five of them, sometimes one or two more, of different colours, styles and lengths. She would proudly say just one word when she came in to pull out a coat to show to her girlfriends: Mink. As she said it, she would let out a long drag of her cigarette, and pronounce a long M, a long N and a long, viscous K: Mhminnkhh. She would remove a cigarette from her red-leather cigarette case as if she were drawing out an amulet. She would fondle it, soften the filter with her fingers, gently and carefully press it into her cigarette holder, and finally light up with the deft stroke of a match on her fingernail − at least so it seemed to me, until Milica told me that her mother always kept in the pocket of her jackets, overcoats and probably even pyjama tops, a small flint from a matchbox, which she would hold against her thumbnail. The smell of Bulgarian rose oil and boiled milk from my grandmother’s apartment was replaced in Milica’s apartment by nicotine, fur, hairspray used to shellac into place the magnificent hairdos of Aunt Ceca and her friends, and the smells of piquant or flowery perfumes with which the furs were doused: Shshanelll. Chchaarlie.Shshammadd.

***

Not long after the perfumes were joined by yet another ear-pleasing name − Riv Ghoshshsh − and Milica’s mattress began to make strange rustling noises, Aunt Ceca was arrested. Only then did I begin to notice the presence of Milica’s father in their apartment. He sat at the dining-room table with his large, bald head in his hands − a pose for an actor on stage who was crying, but he was not crying. He was reading the newspaper, completely engrossed in it, as if he were consuming it letter by letter.

“A common drunkard,” explained Milica. “From there he will remove himself to the couch in the living room where he will snore until morning. Lucky him.”

We learned the particulars about Aunt Ceca’s arrest from my grandmother. The neighbourhood sang its pity in unison for both the children and the father. The neighbourhood women fed them and at every meal dished out lectures along with the food: “She threw caution to the wind without regard for the consequences.” “Impetuous women are like that, and especially Ceca.” “Ceca always loved to be the one to know best.”

My grandmother was not like the other neighbourhood women. First of all, she bore the death of her younger daughter stoically. She instilled fear in people’s bones because she locked her front door so that none of the neighbours could, just like that, whenever they felt like it, sashay into her apartment, and at night she even turned the bolt. Aunt Ceca once told Milica my grandmother lived by Tito’s motto “we do not want what is yours, nor will we give you what is ours.” She kept the curtains of the living-room windows closed, kept the blinds down in the summer until late at night, and never went out onto the balcony, not even to hang out laundry. She was a fearfully strange woman who valued her privacy and in front of whom no one was allowed to say a word about Ceca. She would glare at the busybodies and mutter a sharp and barely discernable “Mm hmm, miscreant,” followed by a quick verbal jab where it hurt the most.

“Ceca’s children should know the truth,” she told our neighbours. “Otherwise their hearts and minds will explode from trying to guess the meaning behind your prattle. And their guts will burst from your newfangled Western recipes you pick up from packaging. If you’re going to copy the West, at least copy the good to replace the bad. You’ve got it backwards.”

Then she turned to us: “Isn’t that right?” I nodded and shrieked: “Yes, that’s right!” even though this had nothing to do with me. Milica looked down, and I couldn’t bear to see her like that. Milica never countenanced a downward gaze, only a head held high. Radoš hid behind Granny and sucked his thumb. “We’re going to my place for a home-cooked meal and home-made pomegranate juice,” she said, and walked out proudly, and we followed her, like liberated war prisoners. I even looked the enemies in the eye and sneered, tossing my head back victoriously.

Granny told us why they “took” Ceca, about how she led a “team” with whom she “did” fur coats, ball gowns, cocktail dresses, business suits, perfume and other luxury items, and that those women to whom she said Mhminnkhh