Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Heliotrope Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

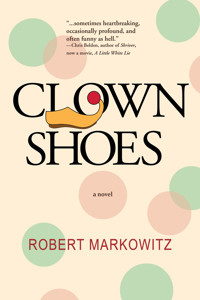

After New York attorney Will Ross gains acquittal for a child abuser and the child is subsequently killed, he resolves to abandon law and become a children's entertainer. Will's change of heart and career is a catalyst for his lover, Clara, who quits her prestigious job to pursue documentary film-making. While the couple are united in their fervor for their nascent careers in art, unexpected challenges rip them apart. Feeling abandoned, Will ventures into his new passion, donning clown shoes, picking up his old guitar, and taking on a special guitar student. Only when the boy's life is threatened does Will take up law again, fighting not only to protect the child, but to clear his guilt and free himself to love.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 334

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Clown Shoes

Copyright © 2023 Robert Markowitz

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by an information storage or retrieval system now known or hereafter invented—except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper—without permission in writing from the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. All the characters, places, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Heliotrope Books LLC

ISBN 978-1-956474-30-5

ISBN 978-1-956474-31-2 eBook

Cover design by Naomi Rosenblatt with AJ&J Design

Typeset by Naomi Rosenblatt with AJ&J Design

To my parents, Selma and Joe Markowitz,

my wife, Linda Kelly, and my daughter, Kate Markowitz.

Also, Lorraine Gengo, whose help with this project was indispensable; Susan Shapiro, who mentored me;

and Naomi Rosenblatt, founder and manager of Heliotrope Books,

who shepherded Clown Shoes.

Tuesday, May 26, 2009 South Salem, NY

My inner matador woke me at three a.m., as he usually did on trial days. He poked me with his banderillas. I ascribed it to a nervous temperament but in talking to other attorneys a lot of them had their own internal tyrants. It’s amazing how many future lawyers are swayed by “Perry Mason,” “L.A. Law,” or “The Good Wife” without knowing what the profession really entails. It’s like falling under the sway of a fast-talking pitchman on late-night TV: Do you want high status but have little idea of what to do with your life? Would you like people to stop asking you questions about your career path? Law school may be for you!

My first wakeful act was to meditate and pray at my makeshift altar, briefly falling back to sleep twice. Shaded by a brass tree of life, the Divine mother and meditating Jesus were all in favor of me getting more rest, but Sekhmet and Ganesh brooked no nonsense.

I got up and stood under the shower, red-eyed from lack of rest. At least, I’d noticed as I glanced around the room, there was no evidence of sleepwalking. After drying off, I dressed in shirt and tie, cool from the closet. Returning to the bathroom to brush my teeth and shave, I nicked myself and clotted the trickle of blood with toilet paper. Frustrated, I waded socks-on into a puddle, and plodded all over the bedroom carpet, leaving footprints. There were no clean socks so I emptied the dirty laundry and matched a pair.

Once in my White Plains office, the keys of my MacBook clicked over the hum of the HVAC system. No lights on. Only the gray glow of the screen to keep the wolves of loneliness at bay. I was loath to admit loneliness. I took pride in never feeling that way. Except that I’d been lonely as hell. Reviewing a practically-hopeless, pre-trial motion to exclude 158 tabs of LSD on constitutional grounds didn’t help much, by the way.

My paper-strewn oak desk dominated the room. I’d bought it years ago for $180 when I only had $700 in my account. Bookcases lined the walls. Most of the volumes were out-of-date case law reporters or legal encyclopedias that I’d picked up for free. Diplomas framed in black, gray, and red were arranged for easy observation from the client chairs.

It may have been some time before I noticed that another sound had blended with the staccato clicks and droning whir. The soft beeping of my phone alarm. Time to go. Without thinking, I picked at the specks of toilet paper still glued to my face, then spit on my finger to remove them.

Breakfast was an Egg McMuffin and coffee purchased on the way to court at a drive-thru window. You deserve a break today. Who speeds into a drive-thru when they have time for a break? As I pulled away with my hot little bag, I felt an outburst coming and sealed the open window.

“I hate being a damn lawyer,” I wailed. “Objection, your honor, I don’t like your smug face! Objection, prosecutor—I hate your blue suit!”

Still driving, I threw my phone at the windshield and it rebounded to the passenger-seat floor.

“I hate fighting losing battles! I’m tired of the weight. It’s too damn heavy! When do I get my reward? I want my fucking reward!” I didn’t even know what that would look like.

I was weeping as I drove down the tunnel to underground parking, found a space, then lay across the front seats, knees bent toward my chest.

My anger turned to cold fear like breathing dry ice. I was pushing back a panic attack.

These seismic waves of dread had increased since Joshua’s death. His mother had been a client, and a mistaken judgment of mine had led to him dying at her hands. Maybe now I could just give in. Allow myself to be afraid and deterred.

But my current client was waiting upstairs, the acid head. Trippers were curious types—nerdy explorers. This one had made the mistake of Instagramming the location of his adventure in real time and the police found him with 158 tabs.

Part of me—the wily, scrappy little savage—was tired of being coerced. He saw his opportunity to strong-arm a bargain. This would be the last trial. No more.

Don’t take advantage, the adult in me chided.

Take advantage? You’ve run us into the ground, buddy. You want me to get up? Give in.

Are you willing to waste fourteen years? This was the adult’s pet refrain. Four years of law school, including a year’s leave, three failed bar exams in three years, and now seven of practicing law.

Shove those fourteen years up your ass, counsel. Else, I won’t move.

The punk hammered the car window until his knuckles were raw. This was no bluff.

Fourteen years.This argument had always prevailed even when it had been thirteen, twelve, eleven, ten. You can’t argue with fourteen years.

The kid reared back to smash his fist once more against the window. The stakes were life.

The adult sighed. I capitulate. The fancy word was a last attempt to pull rank.

Deal, grunted the child.

Of course the adult could always renege. But there are dangers when an urchin loses all faith. He really does have the power to bring down the whole operation.

The battle had the effect of anesthetizing me. I felt numb rather than scared. I drank my coffee and ate my Egg McMuffin, then took my briefcase and walked toward the courthouse.

In the lobby I spied my client. He wore a black top hat, green lion-tamer’s jacket with oversized buttons, orange vest, white gloves, and a purple bowtie which resembled the floppy ears of a beagle. Since he sported a full beard, clown white was applied only around his eyes, setting off the red-ball nose. He was practicing with a color-changing handkerchief.

“Peter,” I said. “You’re not dressed for trial.” I guided him by the elbow toward the exit, talking in a hushed tone. “I can’t try your case. I’m going to have to settle it in chambers before anyone sees you.”

He grinned, as if upsetting my expectations constituted a win.

This was actually a relief. I could probably cut a favorable plea bargain. LSD is an upscale drug of white suburbanites—and don’t think that doesn’t prompt judicial mercy.

“Look,” I continued, ushering him outside. “Why are you dressed like this?”

“These are my work clothes,” he said blithely. “You told me not to speak in court unless I’m asked questions. This,” he gestured to his outfit, “is my message: The judicial system is the oppressive hand of the bourgeoisie that lashes out at anything it doesn’t understand and attempts to apprehend the human soul by incarcerating bodies. Doesn’t my costume convey that eloquently, Mr. Ross?”

His body language said, Let the little people sweep up, I’m too busy being me.

“How dare you show contempt for this esteemed institution,” I said, constraining my volume through clenched teeth. “Do you realize that I’ve spent fourteen years—fourteen years—who do you think you are? Timothy Leary? Wavy Gravy? Who are you to ridicule a system that is the very core of democracy? Wear a humble blue suit, Sir! The men in orange jumpers will be throwing a party for you.”

His face fell. “Am I really going to jail, Mr. Ross? I can’t. I’m no fighter. They’ll carve me up. I don’t do well in close places!” His eyes throbbed blue against clown white. He searched me pleadingly, eyes resting on my bruised knuckles. I, too, did not do well in close places. Taking a deep breath, I steadied myself.

“Look, if you’re willing to plead guilty, I might get you off with a stiff fine and work detail—picking up trash by the highway in a dayglow vest.”

“I’ll plead guilty,” he said. “No jail. I’ll die in there. I know it.”

Rather than feeling superior to Peter, the opposite was true. I was jealous.

“Okay,” I nodded. “Just tell me one thing.” I dipped my head. My voice dropped to a murmur. “Where did you learn to be a party clown?”

He told me about an outfit in lower Manhattan that equipped and trained you in one night. I asked for details as if it were just a vague curiosity to me. It was no frills, he said, glancing at my expensive suit and shaking his head doubtfully. “The class was in a basement on the Lower East Side.”

“Have you worked any parties?” I asked.

“Oh yeah,” he replied, smiling.

“Did you love it?” I couldn’t conceal my keenness on this point so I lowered my eyes to his lime-green shoes.

“You really want to know?” he asked. “I’ve tried LSD, clowning, zip-lining, almost everything. You can’t change your insides with something on the outside.”

Maybe so. But I felt like my feet weren’t quite touching the ground—as if I could rise to the ceiling, weightless. Give up my law practice to become a children’s party performer? It was ridiculous. How could I make a living at it? But I hadn’t felt my blood quicken like this in a very long time, and if I didn’t honor it in some way, I may never again.

I negotiated a favorable plea with the prosecutor. Then it came to me—fourteen years. Damned if I was going to throw it all away for some shlock clown training.

Wednesday, May 27, 2009 South Salem, NY

Norma Wilkes was ranting to the guards and a couple of hand-cuffed, tangerine-suited inmates in earshot. “I don’t remember cutting Joshua. I must be crazy. Can’t remember anything.”

I was her attorney-of-record, having helped her beat misdemeanor child abuse just a month ago. Acquitted by a jury. Her present charge was murder.

I sat in the see-through meeting room watching her approach. She was lean and compact, appearing much younger at a distance. Up close, crow’s feet and marionette lines were etched deeply. Her waxy face framed by straggly dishwater-blonde hair.

She scowled. “I got nobody to help me except you. I’m all alone.”

The guard locked us in and we sat on plastic chairs at the stainless-steel table. The room had plexiglass walls from which you could see the guard booth and the corridor out to the world. I took a deep breath—never liked to be closed in.

I hated her more than I ever remembered hating anyone except maybe Tony Pappalardo, who I’d fought with after every freshman football practice in ninth grade.

I forced myself to look at her. “Why did you do it, Norma?”

She straightened her back. “I don’t need no story for an insanity defense, Mr. Ross.”

The futility of ever getting the truth left an acid taste in my mouth. I met her eyes.

“Did you do it because Joshua went to the police?”

“I remember nothing.” She hesitated. “Nothing.”

That was a lie. But one thing was clear. If I hadn’t secured Norma Wilkes’s acquittal from charges of inflicting cruel and inhuman punishment on her son, CPS would have removed Joshua from the home. The boy would be alive. I wanted to blot myself out, dig a ten-foot hole in the ground and hide.

Her jaw set, lips grew tight. The whites of her eyes were visible below milky-green irises. Her stare was unnerving. I felt my resolve melt like wax from a candle. Why did I grow timid just when I needed to be forceful? Her hand twitched on the steel table. A flash of rage gripped me. I reached out, grabbed her little finger and bent it back.

Blood roared in my ears. “Did you do it because he went to the police?”

“Let go of me!”

She slow-blinked like a cat. That was my answer. I released her. Had I lost my sanity?

Never mind that what I’d just done could get me disbarred—forget that it was cruel. I had become desperate. Desperate men quit trying to be good, believing it’s impossible.

I dropped my shoulders. “I should have counseled you to plead guilty.”

“Why didn’t you?” A sarcastic smile played on her lips. Her voice was low, teasing.

“I believed your story.” She had been very persuasive. Norma’s testimony, more than anything else, won over the jury. She’d stared them down and sold them.

“Believe me now,” she said firmly.

We had won the trial. It had never occurred to me that I was obliged to get the human part right, too.

“Why did you do this to me?” I asked.

She peered up cradling the finger I’d bent back as if it were an IOU. “Help me.”

Reaching for a document in her waistband, she unfolded it, and forced it into my hand. Power of Attorney. “Go to my bank. Take all the money.”

She had been my client. Was I obligated?

Again, she lifted the finger I’d tried to damage. “You punished me.” Kneeling on the concrete floor, she put her hands together in supplication. The fluorescent light made her blonde hair almost colorless. Furrows on her face cast grease-pencil shadows. It was a wretched sight. Despite my promise to myself, despite my anger, I was in danger of acquiescing. But something inside wouldn’t quite yield.

There was a change in Norma’s pearly green eyes. They clouded. Then she looked down at her body as if she hadn’t been aware of her servile posture. Her mouth opened in disbelief, nostrils flared. She slapped her bended knee like she was disciplining a disobedient child. Rage lit her eyes and she glared like a wolf at my throat.

“Get out!” she screamed. “I don’t want you!”

The guard opened the door. My head throbbed. I pressed my right temple to make it stop. I felt ashamed for hurting her.

Norma stared at me from the floor, a sliver of white below the iris. God help a vulnerable boy looking into those eyes. Even as I turned away, I felt them bore into the back of my neck, and track me down the hall.

I was still willing to suffer. That hadn’t changed. I was prepared to labor on, day after day, despising my work. It was ever in the back of my mind that as a lawyer, if not careful, I could do harm. No more was this an abstract notion. I had contributed to a boy’s death.

Outside, rust-colored buildings and barbed wire glimmered in the sun. There had been no choice but to park in the direct rays. A chocolate bar I’d bought at lunch was softening on the passenger seat. I ate it. The sugar daze and stomach ache were darkly satisfying.

Oh to be a clown! Agile, light-footed, effervescent, before an audience of children. Spontaneity had always been the deepest longing of my heart.

But whimsy would not make my mortgage or car payments. No doubt my soul was at risk.

Saturday, June 25, 2009 Kerhonkson, NY

My best friend, Ray, was the closest thing I knew to a clown, and he made his living, such as it was, by playing music for children. We’d met at Mamaroneck High School, and became friends when he’d watched my back as I fought a kid who’d thrown a basketball at my head. Ray was the poster child for the wages of sin. Sin, in the gospel of my parents, was refusing to tailor yourself to the world. He lived in Kerhonkson, a little town in the Catskills, an hour-and-a-half north of White Plains. I picked up the phone and asked him if he would tell me what he knew about playing gigs for kids.

“Why?” he asked. “I thought you settled that LSD clown case.”

“No, for me.” The admission barely cleared my throat.

“You poor bastard. You’re going to quit on account of that boy?”

So, on a rainy Saturday morning I made my Catskills pilgrimage. I drove north with the light bending through the clouds, casting the trees as warlocks, along a snakelike Taconic Parkway. Ray had given me written directions like it was 1982 or something. Turn left at Stewart Gas and then veer right at the next fork. You couldn’t always get a GPS cell phone connection up there.

When I reached his place, I took my guitar around back and entered from the patio as instructed. Ray waved me in through the glass door. I slid it open and stepped into a living room. There he was: greasy hair, disheveled, lying on a couch, half-wrapped in a white cotton blanket, his guitar on the floor. Not a great ad for living the intuitive, spontaneous life. Back in high school, I’d considered an artistic path. Ray’s plight was the outcome I chose to avoid—living broke and alone in a couple of rented rooms. I willingly assumed my parents’ worldview, once boasting to Ray, “Right out of school, I’ll make more money than my father ever did.” Hubris.

A cotton blanket was just one step down from Ray’s usual outfit. When I saw him perform once, he donned the stage with frayed cut-offs, and a bleach-damaged Camp Greylock T-shirt. His hair looked like it had been combed with the jawbone of a walrus. But his guitar work was masterful and his style, mocking, but in good humor. He was so talented he didn’t need to woo the crowd. But I’d already known that from playing gigs with him in high school.

Ray blinked. “I’m sick,” he said, and he looked it—glassy eyes, chin stubble, black hair pasted to his temple, shirt wrinkled like he’d slept in it.

He squirmed on the couch. “Can you make me a cup of tea?”

“Sure.” I was relieved to have something to do. “Has your girlfriend seen the place like this?” I asked.

“No.” He blinked twice as if he’d been sleeping. “She’s visiting relatives in Guyana for two weeks.”

The kitchen adjoined the living room. There was a cast-iron tea pot on a porcelain gas range. I filled the pot from the sink. Tea bags lay across a wood-block cutting board and there was an open jar of Orange Blossom Honey with a spoon buried in it. I held it to the window, examining for ants, then washed two tea cups from the sink.

Ray blew air through pressed lips and shook his head. “It’s a midden pile,” he said apologetically.

“No worries,” I said, waving it off. But I felt embarrassed for him. One more way Ray relied on the world to adapt to him.

“This boy’s death,” he said. “It’s not your fault. You know that, right?” He narrowed his blue eyes. I nodded. But logic was irrelevant. I felt Joshua’s death viscerally, like a weighted vest, the kind they use to contain autistic kids at a juvenile facility I’d visited.

Ray’s house had some elegant features like high ceilings and ornamental molding, but the paint on the ceiling was discolored from water damage. A makeshift wall erected in the living room suggested that this former one-family house had been haphazardly divided into apartments. This explained the patio entrance.

Ray leaned forward. “How’s David?”

“Oh, he’s fine,” I said. “He’s making a fortune in real estate law.”

Ray had always liked my brother. Each was adventurous in his own way: Ray’s nonconformity and unique talent, David’s 2002 Harley VRSC V-Rod and his dream of living in Switzerland.

“Our very own Jay Gatsby,” Ray quipped. He was fond of literary references.

I poured boiling water into cups set with tea bags, rescued the spoon from the honey, and loaded a heaping glob into each, handing Ray a cup.

He nodded thank-you. “Luckily, I have no gigs today.” He drank some tea, balanced the cup on the floor, then slumped back on the couch.

I tasted the tea. Too sweet. “Have you ever performed feeling like this?”

Ray frowned. “The libraries won’t have you back if you don’t show. And you can’t disappoint a birthday child. I once played four gigs in seven hours feeling worse.”

This life clearly had its own demands. “How did you do it?”

“You find a way.” Ray smiled. “I like to keep promises.”

“You played the leads, I strummed the chords,” I said, remembering our teenage band, Bad Chemicals. “You’re a virtuoso guitar player. I’m not.”

I was doing it again. Rationalizing why other people could live artistic lives but not me.

Ray shook his head. “It’s never the guitar playing or the props. Once I went on stage with a borrowed 12-string. I didn’t know where to fit my fingers. One of the best shows I ever did.”

I leaned forward. “Why?”

Ray arched one eyebrow in that Captain Spock way. “Because it’s me,” he said, touching a finger to his throat, “not the guitar.” He sipped the tea. “What would you charge?”

I shrugged. “I don’t know. Fifty dollars a show?”

Ray snapped his fingers. “Start with $150.”

That seemed impossible.

He read my face. “Price is a funny thing. I’ve seen amazing performers charge $250 a show, and along comes a guy at $500 or $600 and he’s getting it. But the $250 guy is better.”

I scratched my head. “So how is the other one getting $500 a show?”

Ray reclined on the couch and mirrored my action, scratching his pasty scalp. “He’s owning it. He’s comfortable with the $500.”

“How do you get that way?”

“I’m not sure,” Ray said. “I’ve gone up gradually.”

“May I ask?”

“Four hundred and I get it. But I’m not immune to dry spells. In fact, last year I was going to quit and my girlfriend begged me not to. So I hung in there.”

I winced to think that it was still so precarious after all the years Ray had put in.

“Feels like quite a jump to make a living at this,” I said.

He repositioned himself on the couch and pointed a finger. “Book yourself a library tour and by the end of it you’ll be in a different place.”

“But what if —”

“Do it.” Ray’s eyes pulsed. “When you get home, pick up the phone.”

“But I hardly remember the chords.” I reached for my guitar.

Ray motioned me to put it down. “It doesn’t matter.”

He must have seen the disbelief in my eyes because he leveled me with a stare.

“It’s really about claiming your turf. At first the world might think you’re bluffing, and refuse to budge. But the moment you know that this is no act, that you’re serious, it will open up.”

My best friend was a bedridden musician cooped up in a godforsaken upstate town but somehow it all felt possible. A warm glow, like birthday-cake candles, filled my chest. It would not have been possible to make peace with this kind of life, never mind get serious about it, before Joshua’s death.

“Can I make you something to eat?” I asked.

Ray motioned to the refrigerator. “There’s not much in there.”

“How about a grilled cheese sandwich? I bet I can find that.”

I scavenged the fridge for bread, butter and cheese. Minutes later, I clapped slick, toasted bread onto some brittle Swiss. A cast iron frying pan on the front burner looked clean enough. I cut another chunk of butter into the pan and fried the sandwich on both sides.

Ray took a slug of tea. “It’s tricky to find your passion. And keep finding it,” he said. “That’s really why I wanted to quit. Nothing got me excited. But now it’s good. I’m into Andean music.” He put down the cup and played something on the guitar that sounded like “El Condor Pasa” by Simon and Garfunkel. Airy. Easy to imagine Andean flutes.

It frightened me that even Ray, who played guitar for a living, sometimes got tired of it. I slid the hot gooey sandwich off the frying pan and served it to him on a plate. Ray put his nose to it with obvious pleasure.

“One last thing.” He gestured toward the next room. “Could you feed the python?”

Saturday, July 11, 2009 Mamaroneck, NY

At this point, I had to consider that I might be a coward. No longer could I claim that I was unaware of what I wanted. The thrill of it had come twice. Once when I imagined myself as a clown and felt so weightless as to rise to the ceiling. A second time, as Ray envisaged my future, and a warm glow, like birthday candles, seized me. Granted, the path was obscure. I could not even see around the next bend. But to deny the markers at my feet, pointing the way, was no longer possible. Even so, I felt paralyzed, unwilling to surrender fourteen years of sustained commitment for a virtual pipe dream. Clients had looked me in the eye across my office desk and entrusted their cases to me. I’d promised them my best effort.

Leaving law would kill a paradigm I’d long carried with me. My great, great grandfather had been a smuggler, my great grandfather an immigrant baker, then came the post-war postman, and the me-generation teacher, and I was to be the golden shiner of this school of fish. It was a tale fraught with ego and family pride, and it was mine.

I had made the mistake of blabbing these ruminations, over the phone, to my mother. Alarmed, and aware that her influence over my life had diminished, she enlisted my brother to remind me of my place in the family evolution. Mom put David up to inviting me to the Orienta Yacht Club, and taking me out on his Boston Whaler. I understood David’s allegiance to our mother. But he could have told her that I was old enough to screw up my own life.

I’d been to the Orienta Club before, situated on the Long Island Sound in Mamaroneck, with an imposing, three-chimneyed stone mansion as clubhouse. I drove up, parked the car in the lot, then headed to the Marleton House. The others were waiting at the entrance. David wore the club uniform: windbreaker, jean shorts, and topsiders. Felicia was on David’s arm, her bathing suit a cutout one-piece with a skimpy cover-up. She was a prosecutor in the D.A.’s office. Clara stood to the side like a third wheel.

“You remember Clara,” David said, after a quick brotherly hug.

Dark bangs, hazel eyes, a profile so perfect you held your breath. She was in a white crocheted beach dress, more bohemian than revealing. I was a fan of her very-local cable news show. When she improvised a joke for a human-interest story, I would laugh. Loud. Alone at my desk in the office. When she read the news, little glimmers of her humanity snuck through. Her eyes would pop if she found something absorbing. When reporting on something objectionable, she’d knit her brow, all her emotions plainly visible—including boredom at times. She had always rung my bell as a woman firmly out of my reach.

I met her eyes, nodded, mumbled unintelligibly. She smiled brilliantly—one of her many endearing expressions I knew from television. Not having any sisters, I didn’t know if girls spent hours honing these looks or if they came naturally. But it worked. On me.

I stuck out with blue shorts and a Breton striped shirt like a French sailor. Allons enfants de la Patrie. Le jour de gloire est arrivé! What the hell was I thinking? When we all walked into the clubhouse together the manager’s eyes lingered.

I lagged behind to avoid being studied—and to watch Clara. Her walk had a rhythm to it. Had she agreed to this because David’s brother, Will, was going through a crisis and needed an excursion? Four is always more comfortable than three. Was it a mercy date?

A 15-foot skiff on the rough Sound is definitely a sit-down boat. David put Clara and me in the rear. I sensed her hesitation, as if she might be used to sitting up front. Felicia got the plum seat beside David. We backed out of the slip and navigated the cove toward the channel. Clara was sitting up straight, angling her neck, as if she didn’t appreciate two heads bobbing between her and the horizon.

The inner harbor was uncrowded but even so, David scrupulously observed the 5 MPH speed limit. He had tackled maritime charts and outboard motors in the same elegant fashion that he’d mastered real estate transactions. David regularly flushed the Whaler’s engine and disconnected the gas line so as to burn all the fuel in the carburetor. He liked systems. I railed against them. That’s likely why he chose real estate and I landed in criminal law.

Clara gazed to her right at the unobstructed panorama of the Long Island Sound. She appeared to sense my attention, and glanced over. But then she fixed her eyes forward on David’s bronzed fingers guiding the wheel.

Rejected ideas for small-talk overtures:

* We’re approaching Bell Buoy 42.

* There’s good fishing for blues here.

* Mamaroneck is the second largest small-boat harbor on the East Coast.

* Did you know I can name who won the World Series in every year since 1921?

We were far enough out so that most of the boats were cabin cruisers and yachts, no longer small crafts.

My brother frowned. “It’s a little choppy for the Whaler,” he said. “I’m going to head north of Turkey Rock.”

He opened a cooler that contained Heinekens, club sodas, slices of Jarlsberg, and Triscuit crackers, bidding everyone to dig in, which they did, passing it around.

Felicia squinted into the sun. “You didn’t take the Wilkes murder case,” she called to me. “Word is you turned her down at the county jail.”

I wondered how much David might have shared about my current career ambivalence.

Felicia twisted her body toward the stern, focusing intently on me. I’d always liked her professionally, she was one of the decent prosecutors.

“Maybe David has told you,” I said. “I’m exploring various things.”

Felicia opened her eyes wide. “Like what?”

I couldn’t quite bring myself to talk about clowns or guitars. “Working with children.”

“As a teacher? Are you going back to school?”

“No.”

I steeled myself. “More like an entertainer. It’s just fantasy at this point.”

A half-smile froze on her face. Her eyes dropped to my fingers as if examining them for leprosy. “You can’t mean that.” Hair blew across her face and she captured it with an elastic and swept it back.

I glanced at David for support. He swiveled toward me, smiled grimly, and quipped, “Yeah—what she said,” then mugged for the women.

Felicia raised a finger at me. “People would die to be in your position. No boss. No defined hours.” She picked up a cheese-covered Triscuit, gesturing with it. “Everybody knows you. Think of the work it took to get you here.”

Of course she was right—if I ignored all my feelings. I peeked over at Clara.

She came alive. “You’re assessing Will from the outside.” Her eyes brightened. “What about inside? What if he’s dying inside?”

It took my breath away. How did this beautiful stranger have any conception of my private thoughts?

“Okay,” conceded Felicia, nodding slowly. “Disaffection with law is an understandable reaction to the tragedy of that boy’s death.” She craned her neck, stretching her back. “But Will can recover. It’s not worth throwing away his whole career.”

No one spoke as four young women in uniform rowed past in a crew shell. Strands of hair escaped their blue visors as they labored in unison.

David grunted. “That’s what we’ll have to do if the motor craps out.” He pointed to a hatch containing emergency paddles. From Turkey Rock, we had gradually drifted back into the open Sound, beyond the bell buoy. Not much a paddle or two could do in rough water.

Clara tilted her head toward Felicia. “Will is searching for his life,” she said. “Not some idea of what his life should be, but his real life.”

Her fervor seemed nonsensical given that we’d never said a word to each other. But strangely, I began to conceive of myself as the man she was describing.

Felicia restrained a mocking smile. “You see Will as doing what you need to do,” she said, coolly inspecting her French manicure.

Clara’s face crumpled. I struggled for a comeback to Felicia. But Clara pulled off her cover-up, stood on her seat, and performed an elegant dive into the roiling sound. She was gone for a few long moments under that cold gray turbulence. Long enough for me to start searching anxiously. When she emerged from the swell, the boat was a good thirty yards past her. We all stood and applauded, even David, poster child for nautical safety. Clara tucked her head and swam a few crisp strokes toward us.

Felicia started screaming, waving her in frantically. I spun to my right expecting a run-away jet ski. Instead, near our boat, a high dorsal fin dipped under the surface, still visible beneath, streaking toward Clara, the shark half as long as our skiff. Needles of terror pierced my gut. Clara glanced behind her, then swam madly toward the boat but made little ground. Ka-shaw-ka-shaw-ka-shaw thudded the blood in my temples. Clara flailed wildly, but the shark was gaining as if she were in a dead man’s float, then it plunged beneath the dusky water. Mechanically, my hands emptied my pockets into the hull. An unfamiliar voice inside said, here I go. Belly first into the white caps, stroking and kicking. I felt a whoosh of current as the big fish sharply reversed course, its gill openings rending as if in shock.

“Hold on to me,” I sputtered. She shook me off, clearly swimming much faster unassisted. David and Felicia crouched over the ladder at the stern and hoisted us up—first Clara, then me. Felicia wrapped her arms around Clara squeezing her so tight she soaked herself. A sun-glinted dorsal fin surfaced a football field away, heading out to sea.

“Oh my God!” shrieked Felicia. “You almost died.”

Clara glowed. Once seated on deck, her teeth kept chattering, even in the strong sun, as if she were releasing shark energy. I re-lived the flash of jagged white scars and surge of flux as the shark had recoiled.

Clara turned toward me, eyes of olive and gold. “Did you see him beneath us?”

I nodded taking her wet hand.

David called to me from the helm. “What got into you?”

I didn’t know. It had something to do with what Clara had said she saw in me. But that bulletproof feeling proved to be temporary, only lasting for our time on the boat. Later, standing with Clara on the dock, I felt lonely, estranged, while David fit the flush muffs over the motor’s intakes and ran water through the hose.

Risking death had scarcely bought me forty-five minutes of peace. Was that why people bungee-jumped from cliffs or leapt out of airplanes with parachutes? All for an hour or so of being enough? What was it that my clown client had said in the courthouse? “You can’t change your insides with something on the outside.” I wasn’t really the man Clara had imagined, the guy who honored his inner calling, the one who’d jumped between her and the shark.

But now she was following me up the rickety dock stairs.

“What’s wrong?” Clara asked, employing one of her myriad endearing expressions, a pursing of soft lips and widening of eyes.

“You are the woman I’ve waited for all my life,” I said awkwardly. “I am totally infatuated,” that wasn’t quite right, “in love with you.”

It was the kind of numbskull move that goes against every rule in the Real Man’s Book of Seduction: admitting clunky, unwieldy feelings about a woman you don’t even know. Nothing makes them run away faster. The mix of despair and inappropriate transparency is not what most females chase after in their Prince Charming.

“Let’s have lunch sometime,” she said.

“Really?”

“You tried to save my life.” She smiled. “That’s worth lunch.”

Clara gave me her number, walked to her Honda Civic, and waved goodbye. I now had a problem. If I called her, I was obliged to be the man she’d projected—one searching, à la Diogenes, for an honest man, an honest me. How had she put it—looking for my real life?

Whether I’d actually become a different man in her presence, or merely posed as one, I needed to live up to that. Which put me in a predicament because I hadn’t decided to leave law.

Sunday, July 12, 2009, Charlestown, RI

I had just a short time to remake myself before asking Clara to lunch. Time to get rid of some baggage:

* Valuing other people’s opinions over my own instincts.

* Trusting that money and status would compensate for self-betrayal.

* Believing joy to be something for other people, mostly children.

Through circumstance or grace, I had a chance with Clara, but only if I detonated an incarnation’s worth of limiting beliefs in a single day.

The antidote was coconuts. I bought five and drove up to my favorite beach on the Rhode Island shore. Charlestown Breachway Beach was where my mother, father, David, and I had spent a vacation week every summer until my parents’ divorce.

The gravel crunched and spit from my tires. Rain on the windshield. Pink flowers rose from the dune beyond. I got out of the car with my Shoprite bag of coconuts. Lining the path to the beach were bushes of white blooms pressed against the rickety red-slatted fence. The tidal ponds along the Rhode Island coast have names like Winnapaug, Quonochontaug, Green Hill, and Ninigret. This craggy shoreline was where I intended to make things right with myself.

I headed across the ocean beach toward the breachway, a sliver of salt water connecting Ninigret Pond to the Atlantic. Granite boulders guarded the breachway, and they posed hard, unforgiving surfaces for cracking coconuts.

The two previous days had been scorchers but this evening was seventy degrees, raining lightly, getting dark. It appeared I was the only one there. The waves were fierce. Charlestown surf doesn’t give a crap who you are. It’s as wild and inhospitable as it wants to be.

Just as I was digging into the bag for the first coconut—“Hey, New York!” A lone fisherman, laden with rod and bucket, approached along the retaining wall. He must have spotted my license plate in the lot.

“I hope you’re not going to make a mess out here.” Jocular, mock-friendly tone. A slew of all-cash bids for Charlestown beach houses had run riot, squeezing out the locals. New Yorkers were an easy target.