Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: AutoClassic

- Sprache: Englisch

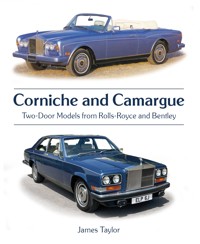

The tradition of the two-door luxury car began early in the history of the Rolls-Royce and Bentley marques. In the 1950s, its most famous realisation was the Bentley Continental, but that name was not revived when the new generation of monocoque models arrived in the mid-1960s. Instead, there were near-identical Rolls-Royce and Bentley variants of a stunningly attractive two-door design that came as either a saloon or a drophead coupé. From 1971, the range gained a clearer identity of its own as the Corniche, with a larger and more powerful 6.75-litre V8 engine. The Corniche remained in production for nearly a quarter of a century, during which time it quite literally stood alone as a symbol of wealth and as the epitome of luxury motoring. The drophead models were always the stronger sellers, and Rolls-Royce drew up plans for a new two-door luxury car to replace the Corniche saloons. In practice, the 1975 Camargue would establish its own market, and the closed Corniche stayed in production until 1980. The Camargue was both glamorous and rare, but it had a quite unmistakable presence and gained its own fame as the world's most expensive production car. This book tells the full story of these iconic ranges, and will be essential reading for owners and admirers of the immortal Corniche and the controversial Camargue.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 288

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TITLES IN THE CROWOOD AUTOCLASSICS SERIES

Alfa Romeo 105 Series Spider

Alfa Romeo 916 GTV & Spider

Alfa Romeo 2000 and 2600

Alfa Romeo Alfasud

Aston Martin DB7

Aston Martin DB9 and Vanquish

Aston Martin V8

Austin Healey Sprite

BMW E30

BMW E34

BMW M3

BMW M5

BMW Z3 and Z4

Classic Jaguar XK – The Six-Cylinder Cars

Ferrari 308, 328 & 348

Frogeye Sprite

Ginetta: Road & Track Cars

Jaguar E-Type

Jaguar F-Type

Jaguar Mks 1 & 2, S-Type & 420

Jaguar XJ 1994-2009

Jaguar XJ-S

Jaguar XK8

Jensen V8

Lamborghini Diablo

Land Rover Defender 90 & 110

Land Rover Freelander

Lotus Elan

Lotus Elise & Exige 1995–2020

Lotus Esprit

MGA

MGB

MGF and TF

Mazda MX-5

Mercedes-Benz Ponton and 190SL

Mercedes-Benz S-Class 1972–2013

Mercedes SL Series

Mercedes-Benz SL & SLC 107 Series

Mercedes-Benz Saloon Coupé

Mercedes-Benz Sport-Light Coupé

Mercedes-Benz W114 and W115

Mercedes-Benz W123

Mercedes-Benz W124

Mercedes-Benz W126 S-Class 1979–1991

Mercedes-Benz W201 (190)

Mercedes W113

Morgan 4/4: The First 75 Years

NSU Ro80

Peugeot 205

Porsche 911 GT3 1999-2023

Porsche 924/928/944/968

Porsche Boxster and Cayman

Porsche Carrera – The Air-Cooled Era

Porsche Carrera - The Water-Cooled Era

Porsche Air-Cooled Turbos 1974–1996

Porsche Sports Racing Prototypes 1963–1971

Porsche Water-Cooled Turbos 1979–2019

Range Rover First Generation

Range Rover Second Generation

Range Rover Third Generation

Range Rover Sport 2005–2013

Reliant Three-Wheelers

Riley – The Legendary RMs

Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud

Rover 75 and MG ZT

Rover P5 & P5B

Rover P6: 2000, 2200, 3500

Rover SDI

Saab 92–96V4

Saab 99 and 900

Shelby and AC Cobra

Toyota MR2

Triumph Spitfire and GT6

Triumph TR6

Triumph TR7

Volkswagen Golf GTI

Volvo 1800

Volvo Amazon

First published in 2025 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2025

© James Taylor 2025

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

For product safety-related questions, contact: [email protected]

ISBN 978 0 7198 4584 0

The right of James Taylor to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Image credits

The author and publishers would like to thank the following for providing images used in this book (page numbers/locations given in parenthesis):

Aguttes: 146

Alf Van Beem: 87 (top)

Bentley Drivers’ Club: 26 (bottom), 36 (bottom)

Andrew Bone: 32 (bottom)

Calreyn88: 113

Mr Choppers: 25 (top), 33 (top), 54 (bottom), 75 (bottom), 86, 88 (top), 112 (bottom)

B. Tyler Coleman: 157

Andrew Farrow/Flickr: 114

Colin Hyams: 148 (top left)

JR3Arlington: 98

Jagvar: 115 (bottom)

Jeremy: 55 (top)

Adrian Kot/Flickr: 83 (top)

Bjørn David Larsen: 57 (top)

Anton Van Luiik: 31

M93: 93 (top)

Magic Car Pics: 9 (top), 74, 75 (top left and right), 130, 131, 132, 133, 134 (top), 135

Paolo Martin: 120 (top left)

Maxwell61: 120 (bottom)

Alexander Migl: 159

Pininfarina: 118

Rolls-Royce: 119, 125, 126 (top), 136, 137

Mike Serpe: 52 (top)

SHRMF: 123, 126 (bottom), 127

Sir Henry Royce Memorial Foundation: 124

John Sweeney: 11 (bottom)

Michael Thompson: 28, 29, 30 (top)

Bill Wolf: 36 (top), 76, 138, 139, 167

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Timeline

CHAPTER 1 BACKGROUND: CARS, COMPANY AND PEOPLE

CHAPTER 2 THE FIRST TWO-DOORS, 1966–71

CHAPTER 3 THE EARLY CORNICHE, 1971–76

CHAPTER 4 THE MID-PERIOD CARS, 1977–84

CHAPTER 5 CORNICHE AND CONTINENTAL, 1985–95

CHAPTER 6 NEW OWNERS AND THE LAST CORNICHE, 2000–02

CHAPTER 7 PROJECT DELTA: THE CAMARGUE

CHAPTER 8 CAMARGUE IN PRODUCTION

CHAPTER 9 MY WAY: INDIVIDUAL REQUIREMENTS

CHAPTER 10 PURCHASE, OWNERSHIP, CLUBS

APPENDIX CHASSIS (VIN) NUMBERS AND PRODUCTION FIGURES

Index

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I have always loved the shape of the Rolls-Royce Corniche, and when I had the opportunity to own one of the models that introduced the shape – a Mulliner, Park Ward Two-door Saloon – I grabbed it with both hands. That car has now moved on to a new owner, and the twin daughters whose arrival prompted its reluctant sale are now staring at their 40th birthdays, but my fascination endures with the whole of what this book calls the Corniche family.

The original Corniche shape remained in production for just short of 30 years, which is a remarkable success story for a car that was a fashion statement as well as a statement of wealth. Good looks do not age, and those beautiful lines drawn up in the 1960s still convey elegance as well as they ever did. Though many cars have fallen on hard times, and few if any remain in regular everyday use, the cars of the Corniche family still cause a stir when seen out in public.

I thought it would be wrong to tell the story of the Corniche family without adding its concluding chapter as represented by the 2000–2002 Corniche – another extraordinarily elegant car that shared some of their DNA but in much updated form. Similarly, there seemed no reason not to include the story of the controversial Camargue in this book, not least because at one stage it was planned to take over from the Saloon versions of the original Corniche. Both models are therefore included here.

Even though I have gathered information about these cars to satisfy my own curiosity for more than 40 years, I needed to dig deeper in order to write this book. That digging deeper involved other people, their knowledge, and their photographs. I am pleased to say a public ‘Thank You’ here to the Bentley Drivers’ Club, Malcolm Bobbitt, Thomas Dinsdale at the RREC, Richard Dredge at Magic Car Pics, Colin Hyams, the late Bernard L King, the Sir Henry Royce Memorial Foundation, Nigel Smith, Don Stott, Bill Wolf, and all those who have made their pictures available for use through online media. I am particularly grateful to Steve Prevett, who provided a selection of pictures showing his superb Camargue, and above all to Marinus Rijkers of www.rrsilvershadow.com who kindly checked through much of the text and was able to add some valuable detail. Whatever mistakes remain can only be of my own making.

James Taylor

Oxfordshire, March 2025

TIMELINE

1966

Announcement of Mulliner, Park Ward Two-door Saloon models of the Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow and Bentley T Series.

1967

Announcement of Mulliner, Park Ward Drophead Coupé models of the Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow and Bentley T Series.

1971

Existing models revised as Rolls-Royce and Bentley Corniche.

Saloon and Drophead Coupé.

Compliant front suspension revisions.

1972

Emissions-controlled engines for USA.

1973

Energy-absorbing bumpers for USA and Canada.

Emissions-controlled engines standardised.

1975

Camargue introduced.

Split-level automatic air conditioning standardised.

1977

Impact bumpers standardised.

Rack-and-pinion steering introduced.

1979

Revised rear suspension based on SZ design.

1980

Fuel-injected engines for California.

Last Corniche Saloon built.

1984

Bentley models renamed Continental; Rolls-Royce continues as Corniche.

1986

Corniche II models for USA (as 1987 models).

Final production of Camargue.

1987

Corniche II models for other markets (as 1988 models).

Bosch fuel injection and ABS made standard.

Last Camargue built.

1989

Corniche III introduced.

1991

Corniche IV introduced.

New four-speed gearbox.

1992

Corniche and Continental production transferred from Willesden to Crewe.

Continental Turbo models built.

1995

Corniche S with turbocharged engine.

Final production of Continental and original Corniche.

2000

New Rolls-Royce Corniche introduced.

2002

Final production of ‘new’ Corniche.

CHAPTER 1

BACKGROUND: CARS, COMPANY AND PEOPLE

The story of the Corniche and Camargue models really begins in the middle of the 1960s with the introduction of a completely new range of cars bearing Rolls-Royce and Bentley badges. Any new Rolls-Royce was an event in the motoring world – and had been for many years – but what happened in 1965 was not simply the routine replacement of one model by a newer one. What happened in 1965 was revolutionary in its own way, because the new cars that Rolls-Royce introduced were constructed in a radically different way from the ones that had gone before. Instead of having a separate chassis frame onto which bodies of different types could be mounted, they depended on monocoque construction, in which the body was in effect a box onto which all the mechanical elements were bolted.

This new range was known within Rolls-Royce as the SY range, and for public consumption the four-door saloons that were its first members were known as the Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow and the Bentley T Series. There were no major differences between them beyond marque identifiers such as badges and radiator grilles, but there was a distinct hierarchical difference. Parent company Rolls-Royce Ltd had bought the ailing Bentley marque back in 1931 and had put the Bentley name onto sporting versions of its own chassis that continued the established traditions of that marque. However, by the early 1960s the Bentley marque had lost much of its sporting character and was treated by its makers as second-best. Insignificant price differences between the Rolls-Royce and Bentley versions of the new SY range made the distinction clear, and within the British class system, which was still alive and well at the time, the subtleties were readily understood.

The convertible Corniche has become a much-admired symbol of the Rolls-Royce and Bentley marques. This one is one of the late models, badged as a Bentley Continental.

The Rolls-Royce Camargue was always rather controversial, but is universally recognised as a symbol of wealth.

Nevertheless, since the early 1950s the sporting aspect of the Bentley marque had been expressed through a series of models that bore the name of Continental. Their chassis were essentially those of the contemporary saloons, but had more powerful engines and other modifications to suit high-speed motoring. The name of Continental had first been used on a Rolls-Royce in the late 1920s, to designate the high-performance version of the Phantom chassis that was intended to be used for the long-distance, high-speed motoring on the European continent that was possible in those days.

This was the beginning of the line that led to the Corniche. The car is a Bentley Continental from the early 1950s, a lightweight fastback with exhilarating performance for its day.

The Continental line was continued onto the S Type chassis from the mid-1950s. This 1956 car had a fastback body similar to that of the original Continental.

There was more than one approved style of coachwork of the Continental chassis. This 1956 car has coupé bodywork by Park Ward.

Fast-forward now to the 1960s, and the Bentley Continental had become an established offering. Rolls-Royce insisted on maintaining its exclusivity by refusing to sell chassis for bodywork that did not meet their standards. Continental bodywork must not be heavy, because that would run counter to the pursuit of high performance. It was designed for owner-driver use (as distinct from chauffeur-driven use), and typically it was sleek and stylish, with only two doors. Special permission had to be given in the late 1950s for a four-door body by the coachbuilder H. J. Mulliner & Co that became known as the Flying Spur type.

So it was that the buying public, rarefied though it was, came to expect the option of a (typically) two-door, high-performance model alongside the mainstream saloon models. Further up the scale, and catering to the chauffeur-driven sector of the market, there had traditionally been a larger and altogether grander chassis on offer, and by the start of the 1960s this was called a Rolls-Royce Phantom V. When the SY range of cars was introduced in 1965, the Phantom continued unchanged, selling as always in much smaller volumes but sustained by the fact that it had no direct competition.

Drophead Coupé models became more common on the S Type Continental chassis. This one carries Park Ward coachwork.

By 1965, a subtle change was taking place. The assignment of the Bentley marque to second-rank status had led to a number of customers requesting cars that had the sleek appearance of the typical Continental in combination with the high-status credentials of a Rolls-Royce. There was no option for the company but to give in – or to lose sales. In 1964, they made available a version of the Rolls-Royce chassis that had the raked steering column of the Bentley Continental, so that it could be fitted with the sleek two-door bodywork typically associated with that car. It blurred the distinction between the two marques to a considerable extent, and would affect the way the cars were marketed in the SY era.

Sleek lines for the 1960s: the ultra-modern Koren-designed drophead body is seen here on a 1962 Bentley S2 Continental.

As a result of these changes, when the new SY range was introduced in 1965, there was no Bentley Continental derivative. Instead, the Mulliner, Park Ward coachbuilding division had worked up some devastatingly attractive two-door designs that would be available with either Rolls-Royce or Bentley identification. The Two-door Saloon was introduced in 1966 and was followed by a convertible (initially called a Drophead Coupé) derivative the following year. None of these models had any pretence to additional performance over that of the saloons from which they were derived; they relied for their appeal purely on their looks and their exclusivity. As the only coachbuilt variants of the SY range available (after a short-lived attempt by James Young), they had the market to themselves.

These cars were much appreciated, but within a couple of years of their introduction there was a distinct feeling within the company that they were not having the impact that they should. New management decided to improve the position, and as a result the company embarked on two related courses of action. One was to give the two-door cars a clearer identity of their own by making a number of visual changes to distance them further from the saloons and by giving them their own marketing name. An enlarged version of the V8 engine was already in preparation (largely to overcome power losses on engines built to meet US emissions control standards), and Rolls-Royce introduced this shortly before making the changes to the two-door cars. So it was that the revised and up-engined two-door models were rebranded as Corniche types in 1971.

The second course of action was to develop a new and deliberately more exclusive owner-driver model that would become the new Rolls-Royce flagship. There were hopes of having this in production during 1973, but setbacks and delays meant that it was not released as the Rolls-Royce Camargue until 1975. This model proved controversial, partly on account of its radically different appearance and partly because it offered no performance advantages over a Corniche Saloon; indeed, with the full emissions control equipment required in some countries, it actually offered less performance. Production volumes were always intended to be limited in order to preserve exclusivity, but they never attained the modest totals that Rolls-Royce had initially anticipated. After a second Oil Crisis in 1979 threatened to undermine sales further, production of the Corniche Saloon was terminated, probably with the aim of protecting Camargue sales. Although buyer interest remained low, the Camargue was allowed to remain in production until 1986, so achieving the twelve-year production life originally predicted for it when the first production examples had been built in 1974.

This is the fixed-head version of the Koren body, pictured on a 1963 S3 Continental. These bodies were so much liked that Rolls-Royce had to sanction their use on a special version of the Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud III chassis.

In the meantime, a plan had been formulated to revive the Bentley marque and give it a clearer and more individual identity. Central to this was the introduction of a high-performance turbocharged derivative of the Bentley Mulsanne saloon in 1986, but in advance of this the Bentley versions of the Corniche convertible were rebranded as Bentley Continental types in mid-1984. The Rolls-Royce versions continued as before, and both continued to sell quite strongly until a replacement was available. In the mean time, Rolls-Royce drew attention to incremental improvements made to the Corniche by giving it a succession of new names. From 1986 in the USA and 1987 elsewhere it became a Corniche II; from 1990 it was a Corniche III, and from 1992 a Corniche IV.

The last Bentley Continental and Rolls-Royce Corniche convertibles on the old SY platform – which had by then been in production for 30 years – were built in 1995, and the role of the big luxurious convertible in the range passed to the new Bentley Azure. For five years, there was no Rolls-Royce successor to the Corniche. Then, prompted no doubt by activities around the change of company ownership at the end of the century, a new Rolls-Royce Corniche convertible appeared in 2000, based on the Bentley Azure. It was short-lived, ending production in 2002, but it ensured that the Corniche name went out on a high note.

THE COACHBUILDING TRADITION

Before World War II, it had been Rolls-Royce policy to manufacture only the chassis for both Rolls-Royce and Bentley cars. Bodywork (‘coachwork’) was left to specialist independent coachbuilders. However, the post-war conditions were very different. The decision was made to offer a Bentley model (the Mk VI) with standardised bodywork that was made from steel by the Pressed Steel company. There would be a Rolls-Royce (the Silver Wraith) that was mechanically related to this, but it would be available only as a chassis for specialist coachwork in the traditional manner; the Bentley chassis, too, was made available without bodywork for bespoke coachwork. The success of the ‘standard steel’ Bentley soon made clear that the way ahead lay with such models, and the early 1950s brought a Rolls-Royce equivalent of the standard-steel Bentley (the Silver Dawn). From then on, it became clear that work for the independent coachbuilders would inevitably decline and gradually fade away.

The is the separate chassis of a Bentley S2, onto which bodies to both standardised and special designs could be bolted.

The 1950s proved to be the last gasp of the major independent coachbuilders, and after 1959 only James Young remained in business – and that only until 1968. However, their long association with the Rolls-Royce and Bentley marques had firmly imprinted on the public mind that bespoke coachwork was a part of the two marques’ heritage. It was this, supported of course by actual demand, that was largely responsible for the ‘coachbuilt’ Corniche and Camargue models. They were not, of course, coachbuilt in the old sense; that was a physical impossibility in the age of the monocoque bodyshell. But they did inherit as much of the bespoke, craftsman-built tradition as they possibly could.

With the Silver Shadow and Bentley T Series came monocoque construction. The main body (here a four-door saloon) was welded to the underframe to create a single, rigid structure.

ROLLS-ROYCE FACTORIES

Since 1945, the headquarters of the Rolls-Royce motor car division had been at Pyms Lane, Crewe, in Cheshire. This factory had originally been built under the Shadow Factory scheme established by the government in the second half of the 1930s, when war with Germany was looking increasingly likely. Shadow Factories were intended to ‘shadow’, or duplicate, the work of the existing factories that produced aircraft components. The thinking was that, if enemy bombing put one of the primary factories out of action, supplies of vital components would still be available in order to keep the Royal Air Force capable of defending the country.

Rolls-Royce had managed the Crewe factory during the war years, and at the war’s end were offered its lease. Crewe was a large modern factory, and it made good sense to move the car division there and focus aero engine work on the older premises in Derby. The government nevertheless retained ownership of the factory until 1973, when Rolls-Royce were able to buy it outright.

The Crewe factory became the centre of Rolls-Royce and Bentley car production after Word War II.

Pyms Lane did not of course make every component of a Rolls-Royce or Bentley car itself. Since 1946, the metalwork of saloon bodies and others made to standard designs had been manufactured by Pressed Steel Ltd at Cowley in Oxfordshire. Custom-built bodies were available from a small number of independent coachbuilders, and in those cases the chassis was shipped from Crewe to the bodybuilder and then the completed car would be checked over to ensure that it met Rolls-Royce standards. Independent coachbuilding had been in decline since 1945, and the number of coachbuilders gradually shrank. Rolls-Royce had already bought out Park Ward in 1939 to provide an in-house coachbuilding facility, and in 1959 it bought out H. J. Mulliner. By 1961, the two had been merged into a dedicated coachbuilding division called Mulliner, Park Ward (and typically known as MPW). This was based in the old Park Ward premises at Willesden in north London, and the former Mulliner premises at Chiswick were closed and sold. Mulliner, Park Ward now became the special-coachwork arm of Rolls-Royce Ltd.

There were further changes at Mulliner, Park Ward during the currency of the models covered in this book. In the early 1970s, anticipating the introduction of a fourth model line in the shape of the Rolls-Royce Camargue, the company bought a redundant factory, formerly used by the Triplex glass company, on the opposite side of Hythe Road in Willesden to the existing Mulliner, Park Ward buildings. This became known as the ‘C Site’ and was partially demolished and then redeveloped to handle both Camargue and Corniche bodies. Further expenditure planned for 1977 was deferred after a long strike (by no means the first) at Mulliner, Park Ward, and then in 1979 the plan was revived and more new buildings were erected for Corniche body assembly on another site in Hythe Road.

All the cars covered in this book depended on one version or another of the L-series V8 engine that was introduced in 1959.

A deep recession in 1981–82 led to falling sales of the Corniche, and also prompted more changes in the Mulliner, Park Ward group of factories. The London Service Station at Hythe Road was closed and a new one opened in School Road, Acton, allowing Corniche construction to be concentrated on a modernised and re-equipped Hythe Road factory. By the end of 1983, the transfer was complete, and both the new factory on the opposite side of Hythe Road and the former Triplex buildings of C Site were put up for sale.

ROLLS-ROYCE THE COMPANY

By the middle of the 1960s, when the story in this book really begins, Rolls-Royce Ltd was a company organised into several divisions, of which the most prominent were the aero engine division at Derby and the car division at Crewe. The Mulliner, Park Ward coachbuilding division was a subsidiary of the car division, with premises at Willesden in London. The car division also owned the Bentley marque, and used it on some of its products. These businesses were stable and profitable, and were generally perceived as a valued British national asset, even though they were privately owned.

It was therefore a major shock when Rolls-Royce Ltd announced on 4 February 1971 that it had entered voluntary receivership. Financial difficulties had arisen with the development programme of a new aero engine called the RB211 that was intended to power the Lockheed Tristar and other airliners, and the company had no option. Rolls-Royce moved quickly to allay public fears by explaining that the car division was in no sense responsible for the problem, and the receiver agreed that it could continue to trade while a lasting solution was worked out.

The solution involved the separation of the various divisions of the company, so that in future the car division and the aero engine division would have to stand on their own feet. On the car side, receiver ER Nicholson authorised the continuation of production without interruption, and this business unit was formally incorporated as Rolls-Royce Motors Ltd on 25 April 1971; this new company acquired the assets of the car, coachbuilding and diesel engine divisions in June. In October, Rolls-Royce (1971) Ltd was established with government support to take over the aero engine business. Perhaps most important was that Nicholson also approved development funds for the Delta project that would later become the Camargue, and also for the purchase of the former Triplex factory (see above) so that the Mulliner, Park Ward coachbuilding operation could be expanded.

The car division’s business continued as usual, but it became clear that public confidence in the name had been badly shaken, even though actual car sales were unaffected. When the car company was floated on the stock exchange in May 1973, the public response was disappointing, and over 80 per cent of the share issue was left in the hands of the underwriters. Eventually, however, the sale of shares realised some £33 million, and Rolls-Royce Motors Ltd became a fully privatised company.

No account of the Rolls-Royce and Bentley bodies of this period would be complete without at least a nod to the founders of the two marques. This is the Hon Charles Rolls…

… and this is the great engineer, Sir Henry Royce.

Rolls-Royce survived the 1970s with a degree of panache, but by the end of the decade was in need of financial support to remain viable for the longer term. A purchaser was found in the shape of the engineering group Vickers plc, to which Rolls-Royce (in the wider sense) had for many years been a supplier of tank and aero engines. As part of the change, Managing Director David Plastow became the Vickers CEO.

Plastow championed the revitalisation of the Bentley brand during the 1980s, and the new cars seemed to herald a rosy future for Rolls-Royce Motors. However, a global economic slowdown at the start of the 1990s led to a slowdown in Rolls-Royce sales, and even though the company was by then offering another exciting new product in the shape of the Bentley Continental R coupé, things began to look grim. In the early 1990s, parent company Vickers decided not to provide the finance that would have allowed the introduction of a new and smaller model that was being planned as the Bentley Java. They preferred to invest in a vast modernisation programme at Crewe that provided a new body plant, a new production line, and a new paint shop – all equipped to deal with more modern manufacturing processes and considerably higher production volumes than their predecessors. These were constructed between 1995 and 1998.

However, by autumn 1997 Vickers had decided to slim down its business and to focus on its core activities. In late October that year, the company announced that Rolls-Royce Motors Ltd was for sale, and sought bids of over £400 million. There was considerable interest from around the world, but the major German carmakers soon became the front-runners, and in 1998 the Volkswagen Group made a successful bid of £430 million. By then, the Corniche and Camargue models had both ceased production, and their positions in the car range had been taken by the Bentley Continental R coupé and the related Bentley Azure convertible. The Azure would soon become the basis of a new Corniche, as Chapter 6 explains, but by then the ownership of the Rolls-Royce and Bentley marques had gone through a complicated transformation.

When Vickers sold Rolls-Royce Motors to Volkswagen, they did so without the rights to the Rolls-Royce name, which had been owned by the Rolls-Royce aero engine company since the split in 1971. Meanwhile, BMW had put in a rival bid for the two marques, and negotiated successfully with the aero engine division for use of the Rolls-Royce name. There followed an interesting interim period in which Volkswagen owned the Crewe factory and continued production of existing Rolls-Royce and Bentley models –including the Bentley Azure convertible – while BMW built a new factory at Goodwood where they started production of new Rolls-Royce models in 2003 under the company name of Rolls-Royce Motor Cars. The final Corniche models, which were based on the Azure, were therefore built at Crewe under Volkswagen auspices in 2002.

THE BRUNEI CONNECTION

During the 1990s, Rolls-Royce entered into a fascinating and highly profitable arrangement to produce a large number of special cars for the Brunei Royal Family. The arrangement has never been officially confirmed by any of the parties involved, although there is documentary evidence of the cars in the archives now held by the Sir Henry Royce Memorial Foundation.

The onward sale of the company in 1998 has prompted some commentators to suggest that the patronage of the Brunei Royal Family was a major factor in keeping Rolls-Royce and Bentley afloat during a difficult financial period; this is probably an exaggeration, but the business certainly did not do Crewe any harm. Prince Jefri alone, the younger brother of the Sultan, is said to have spent $475 million on the two brands during the 1990s.

At its peak, the Brunei collection of cars reached a figure of around 7,000. The Sultan and his brother were very keen on the Rolls-Royce and Bentley marques, and Crewe agreed to provide them with a whole series of custom-built cars that would depend on current production hardware. Many were built in small batches of six or more, and several specialist companies became involved in the project – all of which were sworn to secrecy. The project was known within Rolls-Royce as Blackpool, and its peak of activity appears to have been between 1994 and 1997. By that date, the Brunei collection is claimed to have included more than 650 Bentleys (among which were some relatively standard production types) and more than 500 Rolls-Royce models.

The founder of the Bentley marque was Walter Owen Bentley, seen here in later years.

ROLLS-ROYCE PEOPLE

The Rolls-Royce car division at Crewe was always managed quite separately from the aero division at Derby, although at the start of the period covered by this book the two divisions were part of the same company. By the middle of the 1960s, the key figures in the car division had all been with the company for several years, and would probably have considered themselves thoroughly steeped in the Rolls-Royce way of doing things.

The Managing Director of the car division was Frederick ‘Doc’ Llewellyn-Smith, who had joined the company in 1933 and had become a Board member in 1947. In 1954 he was appointed Managing Director of the car division, and although he resigned from this post in 1967 he remained on the Board as Chairman until 1971. His responsibility was guidance of policy, and it was he who steered the company as it made the transition from traditional separate-chassis construction to the monocoque construction of the Silver Shadow and Bentley T Series cars that sired the models covered in this book.

Geoffrey Fawn took over from Doc Llewellyn-Smith as Managing Director in 1968, although his tenure was relatively short-lived, and at the end of 1969 he moved to a position on the aero engine side. His place as Managing Director was taken by David Plastow, who had come up on the sales and marketing side and would later use that experience to take the company – especially its Bentley marque – in a very positive new direction.

Harry Grylls was the Rolls-Royce chief engineer who oversaw the development of the first monocoque designs.

The leader of the engineering teams in the Rolls-Royce car division was Harry Grylls, who had been with the company since 1930 and had actually worked with its founder Sir Henry Royce. In 1948, he had moved to Crewe as Assistant Chief Engineer, and nine years later, he succeeded Ivan Evernden as Chief Engineer.

Harry Grylls was directly responsible for oversight of the monocoque body structure that was developed for the Silver Shadow family, and of the L-series V8 engine as well, on which the principal design work was done by Jack Phillips. Grylls retired in 1968, having guided into production the earliest of the cars covered in this book, and in his place as Chief Engineer came John Hollings, who would oversee the later forays into turbocharged engines as Technical Director from 1981. Under John Hollings, Macraith Fisher as Assistant Chief Engineer had primary responsibility for the chassis engineering that was so successfully updated over a number of years.

John Hollings became Chief Engineer in the late 1960s and led the further development of the Corniche range and the Camargue.

John Blatchley was the steady hand behind Rolls-Royce and Bentley coachwork designs for more than twenty years.

The head of Rolls-Royce styling during the 1960s was John Blatchley, who had been appointed as the company’s first Chief Styling Engineer in 1951. Blatchley had begun his career as a designer with the coachbuilder Gurney Nutting in 1935, as a protégé of that company’s hugely respected chief designer A. F. McNeil. When McNeil moved to James Young in 1937, Blatchley took over from him. He then joined Rolls-Royce in 1940 to work on aircraft design, was asked to work on the shape of the new post-war ‘standard steel’ body for what became the Bentley Mk VI, and was the obvious choice to head the new styling department some six years later.

John Blatchley oversaw the designs for the Silver Cloud range, the Silver Shadow saloons, and the two-door derivatives of them that became the Corniche models, although he always modestly insisted that the two-door design was actually done by his deputy Bill Allen and that all he had done was to approve it. John Blatchley took early retirement in March 1969, having taken a dislike to what he saw as a new management approach at Crewe.

His replacement at the head of the styling department was Fritz Feller, who oversaw the development of the Camargue styling for which the basic work was done outside the company, by Pininfarina in Italy. He was head of the teams who kept the Corniche fresh throughout the 1970s and into the early 1980s through continual minor adjustments. On Feller’s retirement in 1983, Graham Hull became head of Rolls-Royce styling, and oversaw the final years of the Corniche as well as the development with Pininfarina of the Bentley Azure convertible that succeeded it and was further developed as the last Corniche variant.