Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

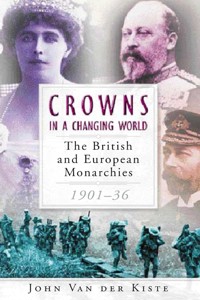

At the death of Queen Victoria in 1901, almost every European nation was a monarchy, most linked by close family ties to her and Edward VII, the "uncle of Europe". Prior to the outbreak of World War I, the personal relationships of Edward, and of his successor and son, George V, flourished with the other royal families of Europe. The closeness of the European families was violently interrupted by the outbreak of war in 1914, and the armistice of 1918 brought three empires, namely Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia, crashing down. Some monarchies were strengthened, and others weakened beyond repair. In this well-researched study, John Van der Kiste has drawn upon previously unpublished material for the Royal Archives, Windsor, to show the realtionships between the crowned heads of Europe in the first part of the 20th century. His account sheds new light on foreign policy leading up to World War I.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 409

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2003

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CROWNS

IN A CHANGING WORLD

ALSO BY JOHN VAN DER KISTE

Published by Sutton Publishing unless stated otherwise

Frederick III: German Emperor 1888 (1981)

Queen Victoria’s Family: A Select Bibliography (Clover, 1982)

Dearest Affie: Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, Queen Victoria’s Second Son, 1844–1900 [with Bee Jordaan] (1984)

Queen Victoria’s Children 1986; large print edition, ISIS, 1987)

Windsor and Habsburg: The British and Austrian Reigning Houses 1848–1922 (1987)

Edward VII’s Children (1989)

Princess Victoria Melita, Grand Duchess Cyril of Russia, 1876–1936 (1991)

George V’s Children (1991)

George III’s Children (1992)

King of the Hellenes: The Greek Kings 1863–1974 (1994)

Childhood at Court 1819–1914 (1995)

Northern Crowns: The Kings of Modern Scandinavia (1996)

King George II and Queen Caroline (1997)

The Romanovs 1818–1959: Alexander II of Russia and his Family (1998)

Kaiser Wilhelm II: Germany’s Last Emperor (1999)

The Georgian Princesses (2000)

Gilbert & Sullivan’s Christmas (2000)

Dearest Vicky, Darling Fritz: Queen Victoria’s Eldest Daughter and the German Emperor (2001)

Royal Visits in Devon and Cornwall (Halsgrove, 2002)

Once a Grand Duchess: Xenia, Sister of Nicholas II [with Coryne Hall] (2002)

William and Mary (2003)

CROWNS

IN A CHANGING WORLD

The British and European Monarchies

1901–36

JOHN VAN DER KISTE

First published in 1993

This revised paperback edition first published in 2003

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© John Van der Kiste, 1993, 2003, 2013

The right of John Van der Kiste to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9927 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Foreword

Prologue

1

‘What a fine position in the world’

2

‘A political enfant terrible’

3

‘No precautions whatever’

4

‘A mighty and victorious antagonist’

5

‘A thorough Englishman’

6

‘A terrible catastrophe but not our fault’

7

‘We are all going through anxious times’

8

‘This wonderful moment of England’s great victory’

9

‘Strength and fidelity’

10

‘Don’t let England forget’

11

‘Such touching loyalty’

European Monarchs, 1901–36

Genealogical Tables

Reference Notes

Bibliography

FOREWORD

The thirty-five years during which King Edward VII and King George V reigned over Great Britain saw a considerable change in the European monarchies. The British Crown and its standing with its subjects altered but little, while many of the thrones which seemed powerful or safe enough in the Europe of 1901 had gone by 1936. This book is an attempt to trace the personal relations between both Kings, and their royal and imperial contemporaries on the continent during that period which saw the last flowering of l’ancien régime, the Great War, and the rise of the dictators.

In accordance with usage generally employed by newspapers of the time, monarchs are referred to by their titles throughout, even after abdication. For example, the German Emperor William II is still ‘the Emperor’ and not ‘the ex-Emperor’ during his years of exile.

I wish to acknowledge the gracious permission of Her Majesty The Queen to publish material from the Royal Archives, Windsor. I am indebted to the following copyright holders for permission to quote from published sources: Collins Harvill (Uncle of Europe, by Gordon Brook-Shepherd); and Constable & Co. Ltd (King George V, by Harold Nicolson).

As ever, I am particularly grateful to my parents, Wing Commander Guy and Nancy Van der Kiste, for their constant encouragement, help, and advice throughout. I am also indebted to Charlotte Zeepvat, Theo Aronson, Steven Jackson of the Commemorative Collectors’ Society, and John Wimbles, for their assistance and for providing invaluable sources of information which I would otherwise have missed; and to the staff of Kensington and Chelsea Public Libraries, for allowing me access to their excellent biography collection. Last but not least, my thanks to Stella Clifford, whose ideas were largely responsible for this book in the first place; and to Rosemary Aspinwall, for her work in helping to see this volume through to publication.

John Van der Kiste

PROLOGUE

Throughout much of her reign Queen Victoria, the ‘Grandmother of Europe’, had connections through family ties with almost every other royal court in Europe. When she ascended the throne in 1837, her Uncle Leopold had been King of the Belgians for nearly six years. Her eldest daughter Victoria, Princess Royal, was married in 1858 to Prince Frederick William of Prussia, destined to reign all too briefly as German Emperor. Her eldest son Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, who succeeded her as King Edward VII, married Princess Alexandra of Denmark in 1863, thus becoming the son-in-law of the Prince destined to become King Christian IX before the end of the year. Her second son Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, married Grand Duchess Marie, daughter of Alexander II, Tsar of Russia, in 1874. Three other daughters and one younger son also married German royalty, although less prestigiously; while in her latter years, two granddaughters married the heirs to the thrones of Greece and Roumania, and another the Tsar of Russia.

Inevitably, the consequent divisions in national loyalties involved them in heated arguments during several of the numerous albeit brief wars that took place in Europe during the second half of the nineteenth century. The Queen was entirely German by blood, with Hanoverian, Brunswick, Saxe-Coburg and Mecklenburg-Strelitz ancestry. Marriage to a first cousin from the house of Saxe-Coburg Gotha had merely reinforced the German element, and her sympathies always remained overwhelmingly German. If that nation’s interests clashed with those of other countries, there was never any doubt which cause must always be upheld.

Early proof was given of this in 1864 when the Princess of Wales’ father King Christian IX was embroiled in war with Bismarck’s Prussia over the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. The bellicose Otto von Bismarck, appointed Minister-President of Prussia in 1862, was determined to raise the standing of Prussia in Germany through a ruthless policy of ‘blood and iron’, and Denmark was his first victim.

The protests of Princess Alexandra, and her husband, that the duchies belonged to her father, carried no weight with the Queen. British public opinion sided firmly with the Prince and Princess, but while the government remained neutral during the short military campaign, Queen Victoria made no secret of her personal support for Germany and her eldest daughter and son-in-law. Family arguments at Windsor became so impassioned at one stage that the harassed matriarch firmly forbade any mention of Schleswig and Holstein in her presence.

Bismarck tested the Queen’s Teutonic partisanship to its limits two years later when he turned on Austria, Prussia’s ally in the Danish war, in order to drive her out of the North German confederation and establish Prussian supremacy in Germany. Among the German states taking Austria’s side on the battlefield was the Grand Duchy of Hesse, whose heir presumptive, Louis, was married to Queen Victoria’s second daughter Alice. Though the Queen was so angered by Bismarck’s behaviour that she was tempted to express her support for Austria, Hesse and their allies, or at least help mediate between both factions, the swift, crushing Prussian triumph put paid to such hopes and ideas. Unpalatable as it was, Prussian hegemony had to be accepted.

In January 1871 the German Empire rose from the ashes of her conquest of the French Second Empire. Queen Victoria’s son-in-law was now His Imperial Highness the German Crown Prince Frederick William, and her eldest daughter Crown Princess. It was a very different united Germany from the liberal nation fondly envisaged by the optimistic late Prince Consort when he had helped to arrange his favourite child’s marriage in 1858, but still his widow did her utmost to show Germany preference even though it no longer retained her affection. It had long been her hope, as it had been that of the Prince Consort, that England would march together with a strong, united, friendly and liberal Germany. While the latter was ruled by Bismarck, now Imperial Chancellor, and reigned over by the ageing, ineffectual Emperor William I, such hopes were slim.

Yet she bided her time for the promise of a new era that would surely follow the accession of her son-in-law as Emperor. Though Crown Prince Frederick William had proved himself on the field of battle as a popular, conscientious leader, he detested the brutality of war and rejected the reactionary politics of Bismarck. Through his mother, born Princess Augusta of Saxe-Weimar, he had inherited liberal and artistic ideas which ran directly counter to those of the Prussian ruling class. During his reign Germany would surely be a very different nation from the warlike empire which his father and chief minister had made it; and his mother-in-law looked forward to that day almost as eagerly as he and the Crown Princess did.

Germany’s march of conquest ceased for a time with the defeat of France in 1871. Yet she was not the only continental power which threatened the peaceful co-existence of European nations during Queen Victoria’s reign. At the height of the Balkan crisis in 1878, there was the probability of war between Russia and England, and she threatened to abdicate rather than let the Tsar into Egypt. English public opinion relished the prospect of war with Russia, much to the alarm of the Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh, neither of whom were popular in England. The royal family were profoundly relieved when the Congress of Berlin found a solution to Balkan problems that satisfied the main powers of Europe for another generation.

The personal and political sympathies of the Prince of Wales did not run parallel to those of his mother. Despite his German ancestry he was less enamoured of the Teutonic element. The ponderous, earnest upbringing which he had endured at the hands of his father in league with the family mentor, Baron Christian von Stockmar, and a succession of unbending tutors, had been interrupted briefly by a visit to the Second Empire of Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie in August 1855, when he was a boy of thirteen. The charisma of the court at Versailles and the capital of Paris, added to the lavish hospitality of their genial hosts, had inspired a lifelong affection in him for France and everything French, very different from the tedium of life at home. These Francophile instincts survived the collapse of the French Empire. Though France became a Republic in 1870, the French way of life altered but little. Family loyalty to his mother and eldest sister did not prevent him from growing increasingly contemptuous of German militarism – as indeed did the reluctant German war hero Crown Prince Frederick William himself.

Their hopes of a brighter German dawn were sadly to be thwarted. As royalties, among them the Prince of Wales, flocked to Berlin for a dinner celebrating the Emperor William’s ninetieth birthday in March 1887, the hoarseness in the Crown Prince’s normally resonant voice was evident as he delivered a speech congratulating his father. Frequently unwell in winter, he was suffering from an unusually persistent heavy cold, which later proved to be an early symptom of throat cancer. When Emperor William died almost a year later, his son – now Emperor Frederick III – was in San Remo, where he had been sent to escape the rigours of the bitter German winter. Already his illness had taken such a turn for the worse that it was evident he could survive for only a few months at the most. Returning to Germany, he reigned for ninety-nine days before dying in June 1888.

He was succeeded by his eldest son, William, whose education and upbringing owed everything to the principles of Prussian autocracy and militarism, and nothing to the more enlightened ideals of his parents. The influence of Bismarck and his followers at the Berlin court had driven a wedge between Crown Prince and Princess Frederick William, whom they held in contempt, and their eldest son, whose differences with his parents had hardened into antipathy. Within weeks of his accession as Emperor William II, it was evident that any hopes for a liberal Germany had died with Frederick III.

By 1894 the major powers of Europe were divided into two armed camps. On one side was the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria, and Italy; ranged against them was the Dual Alliance, signed that year by Russia and France. It was this balance of power on the continent with which Britain was confronted at the dawn of the twentieth century. British statesmen had to decide whether to remain aloof and maintain the traditional policy of ‘splendid isolation’, or throw in their lot with Germany or France. Lord Salisbury, who was three times Prime Minister between 1886 and 1902 and simultaneously held the office of Foreign Secretary for much of his tenure at 10 Downing Street, spoke of the dangers of being allied to one or other of the continental camps; Britain, he warned, would incur ‘novel and most onerous obligations’.

Attempts to reach an understanding with Germany had been made regularly, if somewhat inconsistently, by senior politicians and the aristocracy over the preceding thirty years. The ill-feeling engendered by Emperor William’s callous behaviour towards his widowed mother during the first few months of his reign had long since subsided. The Prince of Wales had been endlessly provoked by his nephew’s behaviour, from public slights such as ‘the Vienna incident’ in September 1888 at which the Emperor insisted that a planned visit by the Prince of Wales to the Austrian capital should be cancelled as he himself was going to be there at the same time, to private arguments such as his passionate interest in yachting at the annual Cowes Regatta, his endless complaints about the British sporting rules, and his obsession with proving the superiority of German yachts and yachting prowess. Yet he appreciated, as did the more far-seeing members of the government, that rapprochement with Europe was of major importance. And this should start with Germany, who was traditionally Britain’s ally on the continent.

This necessity was reinforced in 1899 when long-simmering disputes in South Africa resulted in open conflict. The Boer War, in which the mighty British Empire was ranged against the small but unexpectedly tenacious Boer Republic of President Kruger, brought home to Britain on the outbreak of hostilities that she had no allies in Europe, let alone powerful sympathizers. As a result the pro-German faction in the government, headed by the Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, took the initiative.

The German Emperor paid a brief private visit to Windsor and Sandringham in November 1899, and shortly after his departure Chamberlain made a speech at Leicester declaring that no far-seeing English statesman could be satisfied with England’s permanent isolation; ‘the natural alliance is between ourselves and the German Empire’. It was received coldly by Chancellor Prince Bernhard von Bülow, who commented in the Reichstag a fortnight later that ‘the days of Germany’s political and economic humility were over’, and that in the new century the nation would ‘either be the hammer or the anvil’. His remarks were soon followed by a German navy bill, which in effect doubled the navy programme of 1898 and amounted to the creation of a German High Seas Fleet. The threat was plain for the British Admiralty to see.

Bülow was particularly suspicious of the Prince of Wales, and feared the effect his accession would have on the balance of power in Europe. ‘With his innate dislike of the German Empire and of everything German,’ the Chancellor later noted in his Memoirs, ‘with his strong predilection for France, Paris, and the French, would he, in the event of war, remain loyal and cheerfully true to the alliance with us?’1

None the less there were still regular attempts at bringing about a rapprochement between the two countries, at official and unofficial levels. The last one of the Victorian era was initiated by the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire, who invited Baron Eckardstein, First Secretary at the German Embassy in London, to talk politics with the Duke and Joseph Chamberlain. After dinner on 16 January 1901 the Baron had a long conversation with both men, and on his return to London reported that the Cabinet were evidently of the opinion that Britain’s days of isolation were over. She intended to look for allies, either the Triple Alliance, or Russia and France. She evidently preferred the former to the latter, but if a permanent relationship with Germany proved beyond grasp, the Dual Alliance it had to be.

That same week – almost the very same day that British government and aristocracy were working behind the scenes – the final curtain began to fall on Queen Victoria’s 63-year reign. The Duke of Connaught was in Berlin, representing his mother at celebrations for the bicentenary of the Prussian monarchy. On 17 January he received a telegram announcing that the Queen had suffered a mild stroke while at Osborne, and it was thought advisable to send for her surviving children. When told, the German Emperor proposed to return with him to England. The Duke, who was on better terms with his imperial nephew than anybody else in the family, tactfully suggested that he might not be welcome. But William insisted that his proper place was by his grandmother’s side. Throughout the journey to England he seemed full of high spirits, explaining to his suite that ‘Uncle Arthur is so downhearted we must cheer him up.’

The Prince of Wales came to Osborne on 19 January. Next day he returned to London to meet the Emperor, and both arrived on 21 January. They took their place at the hushed vigil with the Queen’s other children (except the Dowager Empress Frederick, who was too ill to make the journey from Germany) and several grandchildren. By the time the Emperor arrived, her mind was wandering, and she mistook him for his long-dead father. She died at half-past six on the evening of 22 January.

Those who had known the new King, during his long apprenticeship as Prince of Wales, had little doubt that he would play a considerable role in ending British isolation from Europe. None of his ministers could rival his experience and knowledge of European courts during the previous thirty years; and his close family relationship with many of the crowned heads of state on the continent gave him an immediate advantage over the politicians, which it was inevitable he would exploit to the full.

1

‘WHAT A FINE POSITION IN THE WORLD’

Queen Victoria’s death brought her children and her eldest grandson emotionally much closer than they had been for a long time. Among King Edward’s first actions were to make Emperor William a Field-Marshal, his brother Prince Henry a Vice-Admiral of the Royal Navy, and to confer the Order of the Garter on Crown Prince William.

The German Emperor stayed in England for the funeral, which took place at Windsor two weeks later with a formidable galaxy of European royalties in attendance. As well as the Emperor and the new King, Edward VII, King Carlos of Portugal, King George of Greece, King Leopold II of the Belgians, the Austrian heir Archduke Francis Ferdinand representing Emperor Francis Joseph, the Duke of Aosta representing King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy, and the Crown Princes of Denmark, Sweden and Roumania, all followed the coffin on its final journey. Afterwards King Edward’s equerry, Sir Frederick Ponsonby, was shocked to see the German Emperor and two of the Kings standing by the fireplace at Windsor Castle puffing on their cigars. Nobody, he noted, had ever smoked there before.

King Edward was touched by his nephew’s respectful and uncharacteristically subdued behaviour, writing to the Empress Frederick (7 February) that his ‘touching and simple demeanour, up to the last, will never be forgotten by me or anyone’.1

On the last day of his stay in England, the Emperor attended a luncheon at Marlborough House given by the King. The latter proposed his nephew’s health, and the Emperor replied:

I believe there is a Providence which has decreed that two nations which have produced such men as Shakespeare, Schiller, Luther, and Goethe must have a great future before them; I believe that the two Teutonic nations will, bit by bit, learn to know each other better, and that they will stand together to help in keeping the peace of the world. We ought to form an Anglo-German alliance, you to keep the seas while we would be responsible for the land; with such an alliance, not a mouse would stir in Europe without our permission, and the nations would, in time, come to see the necessity of reducing their armaments.2

It was the kind of bombastic speech, combining sincerity and eloquence, in which he excelled. The King must have listened with mixed feelings. Yet shorn of its more fanciful embellishments, it expressed much of the idealism so close to the hearts of the Emperor’s father and maternal grandfather.

For several days after his return to Germany, the Emperor remained under the spell of England, continuing to wear civilian clothes in the English fashion instead of the military uniforms in which his entourage were accustomed to seeing him. Even when officers from his local regiment at Frankfort came to dine, he continued to do so. Some of them felt that he was obsessed with ‘Anglomania’, and were disturbed by the sight of their Supreme War Lord spending so much time attired like an English country gentleman. It was the same Emperor who had irritated his military entourage while staying at Windsor in November 1899, pointing to the Tower every morning and exclaiming with admiration, ‘From this tower the world is ruled.’

Later in February King Edward travelled abroad as sovereign for the first time. Court mourning ruled out any question of a state visit to foreign capitals for several months. This was purely a private journey to see his sister Vicky, the Empress Frederick, for what he realized might be the last time. He was not in the best of tempers after arriving to the sound of a ‘hymn’ being sung repeatedly, which on enquiry turned out to be the Boer national anthem. His irritation was compounded when, having requested an absence of formalities on this occasion, he was received at Frankfurt station by the Emperor in the uniform of a Prussian general.

The weather was unusually fine that February, with snow-clad pine forests around Friedrichshof glistening in the winter sun. Cheered by her brother’s visit, the Empress ventured into the fresh air for the first time for several weeks, asking her attendants to wheel her in her bath-chair along the sheltered paths in the castle park as she and her three younger daughters talked to the King.

Among the King’s entourage was Sir Francis Laking, his Physician-in-Ordinary for several years. The King hoped he might be able to persuade the German doctors to give the Empress morphia in larger doses than they had done so far. However, they viewed his presence with hostility. Ever since Morell Mackenzie had been summoned to take charge of the then Crown Prince Frederick at the onset of his final illness, Berlin had been deeply suspicious of British medical science. The previous autumn Queen Victoria had repeatedly offered, even begged, the Emperor to receive Laking, but he had refused; ‘I won’t have a repetition of the confounded Mackenzie business, as public feeling would be seriously affected here.’3

According to Ponsonby, dinner in the evening was hardly lively, though the Emperor kept small-talk going. His two youngest sisters, Sophie, Crown Princess of the Hellenes, and Princess Frederick Charles of Hesse-Cassel, would cut in tactfully ‘if the conversation seemed to get into dangerous channels, and one always felt there was electricity in the air when the Emperor and King Edward talked’.4

One night the superstitious King was alarmed to find that thirteen people had sat down to dinner, but later he told Ponsonby it was all right as Princess Frederick Charles was enceinte. In fact time was to reveal that they had been safer than he thought, for in May the Princess gave birth to a second set of twins.

All the same, the atmosphere was gloomy. It would have taken more than the aftermath of one family bereavement and the imminent expectation of another to bridge the gap completely between uncle and nephew, in character and temperament so very different, both fellow-monarchs of two mutually suspicious nations.

One evening, Ponsonby was asked to go and see the Empress Frederick in her sitting-room. He found her propped up with cushions, looking ‘as if she had just been taken off the rack after undergoing torture’. After she had asked him various questions about England, and the South African war, she said that she wanted him to take charge of her letters and take them back to England with him. She would send them to his room at one o’clock that same night. It was essential that nobody else – least of all the Emperor – should know where they were. Before she had time to explain any further, the nurse interrupted them and, seeing how tired the Empress looked, asked him to go.

Ponsonby had assumed that she meant a small packet of letters which he would have no difficulty in concealing. At the appointed hour, there was a knock on the door and, to his horror, four men came in carrying two enormous trunks, wrapped in black oilcloth and firmly fastened with cord. From their clothes, he suspected that the men were not trusted retainers but stable-men, quite unaware of the boxes’ contents. At once, he guessed that the Empress wanted the letters published at some future date. Smuggling them away from Friedrichshof would be easier said than done, as the place was probably full of secret police. Hoping for the best, he marked them ‘China with care’ and ‘Books with care’ respectively, and had them placed in the passage with his luggage later that morning. As a member of the King’s suite, however, he was in little danger of having his luggage searched, and nobody queried anything as the soldiers carried them out of the castle later that week. The dying Empress’ wish was fulfilled; her letters remained safely in English hands.*

With his other imperial nephew, Tsar Nicholas II, King Edward’s relations were more harmonious. When Tsar Alexander III had died in November 1894, the Prince of Wales had impressed all fellow-guests as well as the inexperienced new Tsar by his tactful presence at the funeral. The Russian press had been loud in its praise of him, though, like the late Tsar and his family, they had never liked Queen Victoria herself. On his return to England the Prince was congratulated by the Prime Minister, Lord Rosebery, on his ‘good and patriotic work in Russia’, and for rendering ‘a signal service to your country as well as to Russia and the peace of the world’.

Married to her granddaughter Princess Alix of Hesse, Tsar Nicholas had been almost unique among the Romanovs in his respect for and devotion to Queen Victoria. He and the heavily pregnant Tsarina were unable to attend the funeral in February, and they were represented by his brother, Grand Duke Michael (‘Misha’). In his letter, the Tsar sent his condolences (29 January 1901):

My thoughts are much with you & dear Aunt Alix now; I can so well understand how hard this change in your life must be, having undergone the same six years ago. I shall never forget your kindness & tender compassion you showed Mama & me during your stay here. It is difficult to realize that beloved Grandmama has been taken away from this world. She was so remarkably kind & touching towards me since the first time I ever saw her, when I came to England for George’s & May’s wedding.

I felt quite like at home when I lived at Windsor and later in Scotland near her and I need not say that I shall for ever cherish her memory. I am quite sure that with your help, dear U(ncle) Bertie, the friendly relations between our two countries shall become still closer than in the past, notwithstanding occasional slight frictions in the Far East. May the new century bring England & Russia together for their mutual interests and for the general peace of the world.5

Even so, a few months later the Tsar did not hesitate to bring up the vexed subject of the Boer War (4 June):

Pray forgive me for writing to you upon a very delicate subject, which I have been thinking over for months, but my conscience obliges me at last to speak openly. It is about the South African war and what I say is only said as by your loving nephew.

You remember of course at the time when the war broke out what a strong feeling of animosity against England arose throughout the world.

In Russia the indignation of the people was similar to that of the other countries. I received addresses, letters, telegrams, etc. in masses begging me to interfere, even by adopting strong measures. But my principle is not to meddle in other people’s affairs; especially as it did not concern my country.

Nevertheless all this weighed morally upon me. I often wanted to write to dear Grandmama to ask her quite privately whether there was any possibility of stopping the war in South Africa. Yet I never wrote to her fearing to hurt her and always hoping that it would soon cease.

When Misha went to England this winter I thought of giving him a letter to you upon the same subject; but I found it better to wait and not to trouble you in those days of great sorrow.

In a few months it will be two years that fighting continues in South Africa – and with what results?

A small people are desperately defending their country, a part of their land is devastated, their families flocked together in camps, their farms burnt. Of course in war such things have always happened & will happen; but in their case, forgive the expression, it looks more like a war of extermination. So sad to think, that it is Christians fighting against each other!

How many thousands of gallant young Englishmen have already perished out there! Does not your kind heart yearn to put an end to this bloodshed?

Such an act would be universally hailed with joy.

I hope you won’t mind my having broached such a delicate question, dear Uncle Bertie, but you may be quite sure that I was guided by a feeling of deep friendship & devotion in writing thus.6

Much as the King liked his nephew, family affection was tempered by a ready awareness of his shortcomings. ‘Nicky’, he felt privately, was ‘as weak as water’, surrounded by a determined wife and intimidating uncles with far stronger characters than his. Perhaps he suspected that the Tsar was voicing their opinions rather than his own; and he was naturally anxious to explain his country’s position (19 June):

I can quite understand that it was in every respect repugnant to your feelings to write to me relative to the S. African war, though great pressure has been brought to bear upon you. I am also most grateful to you for the consideration you have shown during the incessant storm of obloquy & misrepresentation which has been directed against England, from every part of the Continent, during the last 18 months! In your letter you say that in the Transvaal ‘A small people are desperately defending their country’! I do not know whether you are aware that the war was begun, and also elaborately prepared for many previous years by the Boers, & was unprovoked by any single act, on the part of England, of which the Boers, according to International Law, had any right to complain. It was preceded a few days before by an ultimatum from the Boers forbidding England to send a single soldier in to any part of the vast expanse of South Africa! If England had quietly submitted to this outrage, no portion of her Dominions throughout the world would have been safe. Would you have submitted to a similar treatment? Suppose that Sweden after spending years in the accumulation of enormous armaments & magazines had suddenly forbidden you to move a single Regt. in Finland, & on your refusing to obey had invaded Russia in three places, would you have abstained from defending yourself, & when war had once begun by that Swedish invasion would you not have felt bound both in prudence & honour to continue military operations until the enemy had submitted, & such terms had been accepted as would have made such outrages impossible?

If the S. African Campaign were to be stopped at this moment & England were to recall her troops, we should have no security whatever that the Boers would not commence anew the accumulation of armaments & magazines to prepare for another invasion of British territory. It is not extermination that we seek; it is security against a future attack, & against this, after our experience of the past we are bound to provide.7

With this forthright statement of facts there was no arguing, and although the war was to continue for another few months, the King did not hear again from his nephew on the subject.

South Africa was not the only territory outside Europe in which Britain, Germany and Russia had a particular interest at the turn of the century. For several years the Foreign Offices at St James and St Petersburg had regarded it as almost inevitable that both Empires would clash sooner or later over affairs in the Far East. Though the European powers were supposed to be acting in concert, Russia had for some time pursued an ambitious assault on northern China, in defiance of her European allies, and there seemed little hope of amicable relations being established between them.

His friendship for the Tsar did not prevent the King from suspecting the worst from hostile aims of Russian diplomacy, and he watched Russia’s aggressive action in China with anxiety. The situation had been inflamed the previous year by the outbreak of the Boxer rebellion in China, a nationalist movement provoked largely by the way in which the European powers had been annexing territory. The threat to Europeans in the area intensified in June 1900 after the murder of the German minister in Peking, Baron Clemens von Ketteler. Emperor William inspected a German relief force before its departure for China, and in his speech his tongue ran away with him as he declared that ‘as a thousand years ago, the Huns, under King Attila, gained for themselves a name which still stands for a terror in tradition and story, so may the name of German [sic] be impressed by you for a thousand years on China, so thoroughly that never again shall a Chinese dare so much as to look askance at a German’.8

The effect of the German effort, if not the speech (which would come back to haunt the Emperor a few years later), and of a declaration a few days later that ‘no great decision would be made in the world in future without the German Emperor’, was somewhat impaired by the appearance of an allied force under Russian command (without a German contingent), which relieved Peking in August, six weeks before the German relief force arrived. The Emperor was disappointed and furious with the Tsar for wanting to make peace. Despite an Anglo-German agreement in October 1900 preventing further territorial partition, to which Russia and Japan consented, by the time of King Edward’s accession there was still a state of mutual suspicion. The King wrote to Lord Lansdowne (21 March 1901) of his fears ‘that the Russians have got quite out of hand in China, and that the Emperor seems to have no power whatever, as I am sure the idea of war between our two countries would fill him with horror’.9

The German Emperor was impatient for a solution to the Chinese business, and equally suspicious of the other powers, writing to the King (10 April):

What a time the Powers are wasting over the Chinese Indemnity Question! Money must be paid by the ‘Heathen Chinee’ that is the rule of war all over the world, as he was the cause of the outlay, so the sooner we agree the better! I have already named my sum, & hope that if the British Government takes the same lines we will soon see clear. I am very grieved to hear from friends & private sources that the French & Russians are playing a violent game of intrigues at London, which has so far proved successful, that actually some members of the Government have given vent to the apprehension, that I was siding with the Russians against England! A most unworthy & ridiculous imputation.10

Yet the King’s thoughts that spring and summer dwelt less on affairs in China, than on his sorely-tried elder sister whose sufferings would soon be over. He booked his usual suite of rooms at Homburg in mid-August, so as to be near Kronberg if she should suddenly take a turn for the worse, and the Emperor arranged to be in the area as well. Despite the severity of the Empress’ illness, a rather inconsistent series of statements about her ‘quite satisfactory’ condition gave the impression that she would survive at least another six months.

The Emperor was taking part in Kiel week when he wrote to his uncle, from on board the yacht Hohenzollern (24 July 1901):

I hasten to answer the letter you so kindly sent me with enquiries about Mama’s health as far as I am able from here. When I saw her last on the 15th she suffered much pain & was very low in spirits & downcast. She often grew quite despondent & sometimes gave way to despair. This however not so much from the pain she is suffering – so the doctor says – but on account of the utter helplessness in which she is placed by this horrid illness. The left arm is under ice in a sling & the whole position of her poor, very emaciated body is a bend forward. The right arm & hand is much freer than it was in February & she is able to write letters & notes again. She also says herself that she has more appetite than before, & the fine weather enables her to stay out for the greater part of the day. She takes interest in everything that is going on in the world, politics as well as literature & art, & even is taken up to the ‘Burg’ to superintend the details of the furnishing of the hall & rooms. But it takes a long time to move poor mother as the pain is awful for instance in settling her in her carriage, of course the same on her sofa or bed; & she frequently gives vent [to] most piteous cries which the violent spasms of pain wrench from her. The sight is most pitiful to me considering that one is utterly unable to give the slightest help. Morphia is being used in long intervals & larger doses & does her much good giving her rest for several hours. The vital organs up to this date are quite free & in no way attacked, so that there is nothing to inspire any momentary anxiety; if things go on like this at present the doctors think that it may go on for months even into the winter possibly. It is fearfully distressing!11

Fortunately for the patient and her family, the doctors’ estimates proved rather wide of the mark. On 4 August it was officially announced that her strength was ‘fading fast’, and her children were summoned to her bedside at Friedrichshof. King Edward was on his yacht in the Solent, preparing for Cowes week, when the news reached him. He and Queen Alexandra made arrangements to leave immediately for Germany, but before they could depart they were told on 5 August that the Empress had died early that evening.*

They reached Germany four days later, Queen Alexandra taking a wreath of flowers from Windsor, the home which her dead sister-in-law had loved most of all. The Emperor saw fit to reproach his uncle for lack of feeling in having taken so long to arrive. Such an unwarranted rebuke was hardly calculated to improve the atmosphere.

When he arrived in Germany, the King had a memorandum containing confidential notes on Anglo-German relations from his Foreign Secretary, Lord Lansdowne. Meeting the Emperor at Homburg on 11 August, King Edward was still overwrought at his sister’s death and anxious to avoid risk of any controversial talk at such a solemn time. He therefore handed the Emperor his minister’s ‘confidential’ notes. Perhaps he did so on impulse; maybe it was done in a genuine moment of absent-mindedness. No harm was done, but Lansdowne was horrified. Thoroughly pro-German and, unlike Lord Salisbury, his predecessor at the Foreign Office, firmly in favour of ending British isolation, he resented his sovereign’s somewhat unconstitutional insistence in taking foreign policy initiatives. As Ponsonby observed with masterly understatement, Lansdowne ‘may have been a little jealous at the King being supposed to run the foreign policy of the country’.12

The Empress was buried on 13 August at Potsdam. Her son could not resist another chance to create a military display out of the occasion. The streets were lined with German troops, while King and Emperor both wore the blue uniform of the Prussian Dragoon Guards, marching at the head of the procession to the Friedenskirche. Perhaps the Emperor, who had treated his mother so callously, was making amends by trying to bury her like a reigning Empress; but King Edward found the constant jingle of Prussian spurs at such a solemn time distasteful.

He was relieved to escape next day for Homburg, where he was to take his annual cure, as well as indulge in other pastimes such as an automobile ride with another nephew Ernest, Grand Duke of Hesse. Ernest had nothing of the inflated dignity or military airs of the German Emperor, whom he loathed, and the King found him much more congenial company.

Ten days later King and Emperor met again at Wilhelmshohe for what were intended to be serious political talks. They got off to a bad start with the King uncomfortably squeezed into his Prussian Colonel-in-Chief uniform. Although the court was still in mourning for the Dowager Empress, and he had expected no pomp and ceremony, he was greeted with a parade of fifteen thousand German troops. By 2 p.m., when the last salute on the march past was taken, he was starving.

The Emperor had been well briefed on Maltese affairs, and said how interested he was to hear that the British government was considering granting the Mediterranean island its independence. As the King had heard no such thing, he was most indignant with his ministers at home afterwards. That had been beyond the King’s control; but the confusion over the Anglo-German discussions was not. The memorandum which he had carelessly handed to the Emperor had dealt with matters which could best be discussed between both sovereigns, such as the indemnities sought by Western governments from China after the Boxer revolt,* and relations with the ruler of Kuwait, where it was believed the Germans were planning to build a terminus for a trans-Caspian railway. The King was uninterested in such details, which were primarily the concern of his ministers and civil servants. In any case he was in no frame of mind to make concessions to his nephew. The talks achieved nothing, and the exhausted King arrived back at his hotel in Homburg, heartily thankful that this trying meeting was over.

After two weeks at Homburg, invigorated by his ‘cure’, he left for Copenhagen on 6 September. Here he joined a family party hosted by his widowed father-in-law, King Christian IX. Also present were Queen Alexandra, her sister the Dowager Tsarina of Russia, their brother King George of the Hellenes, and Tsar Nicholas II. At Copenhagen the King received a deputation congratulating him on his accession, and in reply to the address he alluded to his first visit to Denmark nearly forty years earlier, and to the great affection he had always had for her people.

On 19 December Count Metternich, the new German Ambassador in London, was officially informed by Lansdowne of the British government’s decision to suspend Anglo-German talks. It was a step the British Cabinet took with some regret, but they had good reason to do so. The state of public opinion in Great Britain and Germany was not favourable to such a policy; the government had no wish to alienate France or Russia by involvement with the Triple Alliance; and it was necessary to avoid irritating the United States, displeased by the hostile and provocative attitude which Germany had adopted towards the Monroe Doctrine.

King Edward agreed wholeheartedly with this decision, though whether Crown or Cabinet was more determined to abandon their efforts at an alliance was hard to say. Although he regarded foreign policy as his own preserve to an extent, he was content to leave certain decisions to his ministers. Whereas Queen Victoria would have considered Anglo-German alliances paramount, and defended if not actively encouraged her ministers to this end until late in life, King Edward had no such sentimental attachment to their German ancestry. More than his mother, he appreciated the impossibility of trying to remain on friendly terms with the Second Reich. And even more than his mother, whenever he looked at Germany he was perpetually haunted by the ghost of ‘Fritz’. Had Emperor Frederick III not been struck down by cancer, it would have all been so different.

Despite this formal end to negotiations, the Emperor would not give up hope. Although he seemed to be obsessed with trying to score off his uncle much of the time, he found it impossible to sever the emotional ties that bound him to Britain. When the King found the Highland suit that had belonged to Frederick III and had just been discovered while clearing out an accumulation of long-untouched possessions at Windsor Castle, he sent it to Emperor William as a Christmas present.

The latter was delighted, and his letter (30 December) from Berlin thanked his uncle for ‘the most touching and splendid gift’:

. . . it was a most kind thought, and has given me great pleasure – I well remember having often stood as a Boy before the box in Papa’s dressing Room, and enviously admiring the precious and glittering contents. How well it suited him, and what a fine figure he made in it. I always wondered where the things had gone to, as dear Mamma never said anything about them and I had quite lost sight of them. The last time I wore Highland dress at Balmoral was in 1878 in September when I visited dear Grandmamma and was able to go out deerstalking on Lochnagar . . .

The vanishing year has been one of care & deep sorrow to us all, and the loss of two such eminent women as dear Grandmamma and poor Mother is a great blow, leaving for a long time a void which closes up very slowly. Thank God that I could be in time to see dear Grandmamma once more, and to be near you and Aunts to keep you in bearing the first effects of the awful blow.

What a magnificent realm she has left you, and what a fine position in the world. In fact the first ‘World Empire’ since the Roman Empire. May it always throw in its weight in the side of peace and justice – I gladly reciprocate all you say about the relations of our two Countries and our personal ones; they are of the same blood, and they have the same creed, and they belong to the great Teutonic Race, which Heaven has entrusted with the culture of the world; for apart from the Eastern races, there is no other race left for God to work His will in and upon the world except ours; that is I think grounds enough to keep Peace and to foster mutual recognition and reciprocity in all that draws us together, and to banish everything which could part us. The Press is awful on both sides, but here it has nothing to say for I am the sole arbiter and master of German Foreign Policy and the Government and Country must follow me even if I have to ‘face the music’. May your Government never forget this, and never place me in the jeopardy to have to choose a course which would be a misfortune to both them and us.13