Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Dedalus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Dedalus Retro

- Sprache: Englisch

"Welcome to a moving and compassionate first novel by Ros]Franey, Cry Baby. The subject is baby-battering. The book is short. The insights are astute. It has the stamp of real talent and augurs well for the future success of a writer who has a genuine feel for her craft." Peter Tinniswood in The Times "It is a moving book that seriously questions the pressures of motherhood and whether every woman should feel 'naturally' maternal. Like a modern Raskolnikov, Lisa's actions are frenzied, despicable but identifiable-with. Franey writes with a piercing insight into human nature which is astounding for a first novel." Time Out "Suspense and foreboding move alongside the chief players in this auspicious novelistic debut by a British writer. Franey deftly engages the reader's emotions as she spins this disturbing tale." Publishers Weekly "It is fortunate for those perpetrators of child abuse that a novelist has at last managed to highlight their trauma in an imaginative and sympathetic light. The cold, stark and unpleasant facts of child abuse usually come to us from newspapers and the real skill of Cry Baby is the way the novel explains all the complications which force a person into abusing their own child." Social Work Today

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 336

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedalus RetroCRY BABY

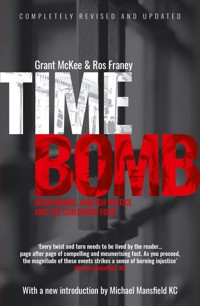

Ros Franey began working in television just as Cry Baby, her first novel, was originally published in 1987. Her career has been in documentaries, predominantly for ITV, Channel 4 and the BBC.

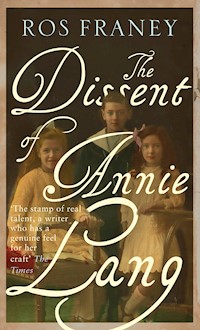

Her novel The Dissent of Annie Lang was published in 2018. She has also written non-fiction.

Published in the UK by Dedalus Limited

24-26, St Judith’s Lane, Sawtry, Cambs, PE28 5XE

www.dedalusbooks.com

ISBN printed book 978 1 915568 00 7

ISBN ebook 978 1 915568 01 4

Dedalus is distributed in the USA & Canada by SCB Distributors

15608 South New Century Drive, Gardena, CA 90248

[email protected] www.scbdistributors.com

Dedalus is distributed in Australia by Peribo Pty Ltd

58, Beaumont Road, Mount Kuring-gai, N.S.W 2080

[email protected] www.peribo.com.au

First Published by Dedalus in 1987, reprinted in 1988

Retro edition in 2023

Cry Baby copyright © Rosalind Franey 1987/2023

The right of Ros Franey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Typeset by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP Catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Altogether, Alice did not like the look of the thing at all. “But perhaps it was only sobbing,” she thought, and looked into its eyes again, to see if there were any tears.

No, there were no tears. “If you’re going to turn into a pig, my dear,” said Alice seriously, “I’ll have nothing more to do with you.”

Lewis Carroll

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

To Morley,

without which …

CONTENTS

1. THE PRESENT — JULY 1974

2. THE PAST — TO SEPTEMBER 1972

3. THE PRESENT — JULY 1974

4. THE PAST — OCTOBER 1972

5. THE PRESENT — JULY 1974

6. THE PAST — DECEMBER 1972

7. THE PRESENT — JULY 1974

8. THE PAST — JANUARY 1973

9. THE PRESENT — JULY 1974

10. THE PAST — JANUARY 1973

11. THE PRESENT — AUGUST 1974

12. THE PAST — JANUARY 1973

13. THE PRESENT — AUGUST 1974

14. THE PAST — MAY 1973

15. THE PRESENT — AUGUST 1974

16. THE PAST — SEPTEMBER 1973

17. THE PRESENT — AUGUST 1974

18. THE PAST — SEPTEMBER 1973

19. THE PRESENT — SEPTEMBER 1974

20. THE PAST — SEPTEMBER 1973

21. THE PRESENT — SEPTEMBER 1974

22. THE PAST — OCTOBER TO DECEMBER 1973

23. THE PRESENT — SEPTEMBER 1974

24. THE PRESENT — SEPTEMBER 1974

25. THE PRESENT — OCTOBER 1974

26. THE PRESENT — NOVEMBER 1974

27. THE PRESENT — DECEMBER 1974

28. THE FUTURE — FEBRUARY 1976

1. THE PRESENT — JULY 1974

The baby’s arm was broken. A staff nurse bustled from the cubicle hugging X-rays. Exhaustion pricked at the corners of Lisa’s eyes. She longed to curl up and sleep but the couch was high and uninviting. On it lay Katie, face spongy from prolonged and violent tears. The doctor, perched on a stool, wrote notes at an awkward angle on his knee. The cubicle was stuffy and far too small for the three of them. Beyond its faded curtain Lisa heard the dayshift starting to arrive.

‘Dotty! Gosh, is that the time? How’d it go?’

‘Super. Bistro Vino. We’re going to Guildford on Saturday!’

Suppressed giggles.

Lisa waited stiffly. The doctor paused in his writing. ‘Half-past three you said, Mrs Heelis?’

‘I think so,’ murmured Lisa.

‘And how long were you absent from the room?’

Lisa’s heart fluttered. ‘She needed changing. I just went into the sitting room for nappies.’

‘You keep the nappies in the sitting room?’

‘No. I mean, I hadn’t unpacked the shopping.’

‘You went to get a new pack. How long did that take?’

Lisa hesitated. The doctor’s eyes glazed. ‘Approximately?’

‘Half a minute,’ Lisa said.

‘And the baby had rolled — thrown herself in a tantrum or whatever — to the right, and fallen off the bed.’

‘No, that’s the wall,’ said Lisa. Of this she was sure. ‘She fell to the left.’

The doctor nodded at the baby. ‘It’s her right arm, Mrs Heelis,’ he said wearily.

Lisa’s hands were sweating. She leaned across the couch for support. Her hair brushed the baby’s feet. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said, tears swelling in her tightened throat. ‘I’m so confused. I don’t know anymore.’

‘Okay, it can be sorted out later. Mr Drew will be here soon. He’ll patch her up in no time. Would you like something to make you feel a bit calmer?’

‘I’m all right,’ Lisa said.

When the doctor had gone, she sat on in the airless cubicle, scarcely aware of the baby beside her. Her head felt as if it were full of dough which failed, nonetheless, to protect it from the intrusion of sudden noise: the rattle of a loaded trolley crossing the floor outside; the squeak of crêpe soles. After a while she became aware of a low and persistent murmur of voices. Questions, answers and the tone of information being imparted. Lisa stirred, raised the curtain and looked out. Night and day shift nurses clustered along a bench beside the sister’s desk in their clean cotton. The new nurses made notes. ‘They’re talking about me,’ thought Lisa, and dropped the curtain guiltily.

Exhausted by her own crying, Katie wriggled and snuffled, regarding her. The fractured arm scared Lisa. She was nervous of touching the child, laying instead her cheek on the couch against the paper sheet close to the baby’s face. ‘I do love you,’ she whispered. ‘Honest I do.’ She was dozing when they came to take Katie away.

An hour later, Lisa was back in the waiting area sitting on one of the long plastic-covered benches, a polystyrene cup half full of tea on the floor beside her. It was still early and the benches were unoccupied, save for an old man who sat smoking, leaning over the floor as if he were about to be sick, and a woman and child, neither of whom looked in the least ill, sitting opposite Lisa. A black cleaning woman carefully swept the floor. Lisa watched her. She worked with economy of movement, handling the broom as if she were engaged in some highly-skilled craft. With a minute flick of the wrist she manoeuvred fluidly around the legs of each bench, stopping to examine here a new gash in the plastic, there a cigarette burn, with soft expressions of disapproval. Before her she marshalled the long night’s toll of cigarette butts, cellophane wrappings and cups, leaving in her wake a shining pool of vinyl.

‘Finished, love?’ she asked when she reached Lisa, stooping to pick up the beaker of cold tea.

‘Yes, thanks,’ Lisa said.

‘It’s terrible,’ the woman commiserated. ‘I won’t drink it. This rubbish from a machine.’

The staff nurse who had brought the X-rays appeared from round a corner where the cubicles were and approached Lisa. She carried a clipboard.

‘Mrs Heelis?’ she asked briskly, as though they hadn’t met before.

‘Yes,’ said Lisa. The nurse sat down beside her. ‘There’s just one or two details we need which would help us. Was your daughter born here?’

‘Yes.’

‘Which consultant were you under? Do you remember? Was it Mr Rogers or Professor Stone?’

‘Rogers, I think. I never saw him, though.’

‘We’ve got the baby’s date of birth. Have you ever been treated in hospital for anything else?’

‘Here, you mean?’

‘Well, anywhere.’

‘The doctor already asked. I told him I hadn’t.’

‘I see. What was your name before you were married?’

‘Brown. I told him that, too.’

‘I’m sorry, Mrs Heelis. It’s all on the baby’s file, I know, but Mr Drew’s got that. This is just for social work.’

Lisa glanced quickly across at the woman opposite, but she was engrossed in reading to her child. ‘What d’you mean?’

‘Just for the record. Don’t worry.’

‘I haven’t got a social worker.’

‘No, well that’s fine. Your health visitor will pop round to see you soon.’

‘What for?’

‘Just to make sure you’re all right. I expect you want to know how your little girl is?’

‘Yes, of course. Have they finished?’

‘Nearly. And she’s going to be right as ninepence.’

What a daft expression, Lisa thought. ‘I think that’s all the questions,’ added the nurse, consulting her notebook. ‘Oh no, there was just one thing. Dr Douglas wanted me to ask you which way was she lying on the bed?’

‘What d’you mean?’ asked Lisa.

‘When you went to get the nappies, was it her head or her feet facing the pillow?’

‘Why does he need to know that?’ Lisa’s brain wouldn’t function. She couldn’t work out which way the child ought to have been lying to break its right arm.

‘I don’t know. Something to do with the angle of the fracture, probably,’ said the nurse. ‘I think he was confused about which way she fell.’

There was a pause. They looked at each other. Lisa said: ‘She was lying across the bed. Her feet were facing me.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yes, oh yes. Quite sure. I was going to change her nappy.’

‘All right. I’ll put it in the notes, then. It’s only worth putting in if you’re really certain. If I were you I’d have been so upset I wouldn’t have been able to remember a single detail.’ She smiled. Lisa trembled.

‘What am I supposed to do?’ she whispered.

The nurse laid a hand on Lisa’s arm. ‘Nothing. You can go home soon. Don’t worry about a thing, Mrs Heelis.’ Lisa started to cry. ‘Would you like me to call someone — your mother?’ suggested the nurse, kindly.

‘No, no,’ wept Lisa. Then thinking this sounded rather ungracious, ‘She’d only worry.’

‘Your husband’s away, isn’t he. Any special friend? Someone who could go home with you and stay for a bit?’

‘I’ll be all right,’ Lisa said, mopping at her face. The nurse departed. Lisa leaned back and closed her eyes. Phone her mother! The very notion revived thoughts that had nagged at her throughout the night. Once again she pushed them away, but this time her tired brain refused to put up a fight. Memory flooded in.

2. THE PAST — TO SEPTEMBER 1972

We called it ‘being wicked.’ It was a secret between you and me, d’you remember, Mother? — the only one we ever shared. The first time it happened (at least, the first time I remember) was when I was sick in the night in bed and I cried. After a long while, such a long while, you came. Mummy’s coming; thank you, Mummy. I don’t know what your words were, but your voice was wrong. The way you yanked at the sheets to change them was more terrible than being ill. Once — how old was I? Three or four, something like that; I could reach up to the bolt on the lavatory door — I made mud pies with your pastry cutters. ‘Look, Mummy, cakes.’ I hadn’t learnt, you see, that something which was all right one day wasn’t all right the next. And suddenly I knew when you came at me this was one of the days when it wasn’t; and I dodged, being little, around the kitchen table and ran, faster than fairies, faster than witches, into the hall and locked myself in the lavatory because I could reach the bolt. And I sat on the floor and hugged my knees with the tiles cold on my knickers. I stayed there ages and the house was so quiet I thought you had gone. And I was scared because if you had really gone it was because I was wicked; but if you were only pretending, you would get me. The walls leaned over and I couldn’t breathe. I was frightened to go but there was no air left and I couldn’t stay. So as quiet as a cat I worked the bolt, slowly, slowly; and I opened the door a crack; and out I crept, across the hall to the stairs. Because I knew that if I could get upstairs to my teddy it would be all right. The house was silent. It was sunny through the glass of the front door and I tiptoed across the sun. Then suddenly your shadow, Mother, and I screamed. That night you sat on the edge of my bed and made me understand (it was the first time I understood) that I made you get cross because I was wicked. ‘Daddy will come home tomorrow’ you said. ‘But I tell you what,’ you said. ‘It shall be our secret, yours and mine. I’m not going to tell Daddy this time about how wicked you’ve been.’ ‘No, Mummy.’ ‘So what do you say?’ you said. ‘I’m sorry.’ ‘That’s a good girl. And what else?’ ‘Thank you, Mummy.’ Thank you for not telling Daddy. And indeed neither on that occasion nor on any other was Daddy ever told.

Stanley Brown, Lisa’s father, was a salesman, travelling sometimes in painkillers, sometimes in insurance. Later he switched to insurance full-time. Travelling in painkillers meant being away from home all week and it was usually when he was away that Lisa was wicked. She tried very hard not to be. She planned her small life around avoiding it. But for a long time her mother, continued to lose her temper just the same; the unpredictability of these rages, coupled with the fact that afterwards they seemed to make Edith Brown as unhappy as they made her angry, only increased Lisa’s sense of guilt.

She was an only child, forever on the fringes of other people’s dramas at school; solitary in holiday time because they forgot to include her. Instead she occupied a grave world of romance which absorbed her more fully than real friendship could. Within the lemon-painted walls of her bedroom — a shade chosen with care by her mother and father — she would read and dream for as many hours as decency permitted. What was this mystery, this melting into eternal bliss? She prayed to attain it, choosing her heroines with care. But behind her musings lurked the knowledge that, touched by sin, she was already lost.

One chilly Sunday in church when Lisa was nine, her wandering attention was captured by a single sentence: ‘The wilderness and the solitary place shall be glad for them; and the desert shall rejoice, and blossom as the rose.’ The congregation knelt to pray and when Lisa spread her fingers to peer out she saw this same image in a vision before her. Across the beige linen skirt of the girl kneeling in the pew in front a single rose was indeed budding, a crimson glow above the dingy varnish of the pew. Lisa blinked and looked again, but the rose remained; and when, the congregation having sat for the notices, they stood to sing a hymn, she saw to her amazement the bud had opened in a rubescent blaze, flowering indeed in the desert of drab frocks. Lisa glanced sideways up at her mother, but Edith Brown sang on until, feeling Lisa’s eyes upon her, she looked down and frowned. Lisa held her mother’s gaze, then looked pointedly at the rose and back at her mother. Edith’s irritation deepened. She did not follow the direction of her daughter’s eyes but shook her head and continued singing. Everyone sat down for the sermon, through which Lisa fidgeted impatient to see what would happen next. What would God do to you if He gave you a Sign and you couldn’t work out what He was getting at? She tried to compose herself into a state of devotion, but the sermon seemed so long that it occurred to her a whole garden of roses would have had time to burgeon before the next hymn. At last the vicar shuffled his notes together and intoned, ‘In the name of God the Father, God the Son …’ When they stood, Lisa gaped at the girl in front, who all unawares was fishing for her collection money. The rose had swollen and spread in a profusion of overblown petals. This time Mrs Brown saw it too and acted promptly. Leaning forward, she tapped the shoulder of the woman standing next to the girl; alarm suffused the woman’s face as she saw the rose. Lisa held her breath. In an instant the woman had whipped off her coat and placed it round the girl’s shoulders. Bending, she whispered urgently in the girl’s ear — who in turn blushed and clutched the coat about her. Undercover of the hymn, the two women left the pew and tiptoed down a side aisle through the sound of tinkling coins to the exit. The latch clattered and they were gone. Mrs Brown resumed her singing, but Lisa’s lips barely moved and she filed from the church at the end of the service in a state of awe and perplexity.

‘What was it?’ she asked eagerly as they descended the steps and walked towards the bus stop. ‘Was it a rose, or what?’

‘Rose? What are you talking about?’

‘It was like a flower that grew.’

‘I don’t want to talk about it, Lisa. It’s not nice,’ said her mother.

Lisa bit her lip. Will growing up be better than this? she wondered. There was fear in her stomach.

She thought that would be the end of it, but as they walked through the damp streets to the echo of Mrs Brown’s high heels, her mother actually broached the subject.

‘What were you doing,’ she asked, ‘distracting me before the sermon?’

‘It was the rose,’ said Lisa fearfully. ‘It had grown, you see.’

‘Don’t be dirty.’

‘I’m not being dirty,’ cried Lisa. ‘I thought it was a miracle.’

Mrs Brown grunted. ‘It’s not a miracle,’ she said drily. ‘It’s the opposite.’

‘But what is it, then?’

‘It’s something women have to put up with.’

‘Why mustn’t you talk about it?’

‘Because it’s not nice. It’s messy and it smells and it gives you a pain.’

‘What for?’

‘Because it does. That’s what happens.’

‘But what happens?’

‘You saw for yourself, Lisa. We bleed.’

‘Bleed?’ echoed Lisa, though it was the ‘we’ that tightened her fear into specific dread.

‘It’s to do with having babies,’ explained Edith in a rush. ‘But all women get it whether they have babies or not. You’ll get it in a few years. When I was young we called it the curse.’

‘Why?’

‘Because it’s like having babies and the pain and everything else. It’s God’s punishment to Eve because she tempted Adam. We can’t get out of it.’

Lisa was transfixed with horror. For the rest of the day she felt that life as she knew it had ended. On Monday in break she sought out Caro Atkins, the only girl at school who had come anywhere close to being her friend. But Caro sneered at her.

‘Crikey, she hasn’t told you that old rubbish? My sister got her periods this year. It’s nothing. It doesn’t hurt. Your mum doesn’t half say some stupid things.’

‘She said it was a curse!’

Caro burst out laughing. ‘ ’Course it’s not, stupid. Your mum’s round the bend.’

Lisa was reassured, but not entirely. It might not be a curse for Caro, but in her own house, where any kind of effluxion was on the instant dammed, drained, bleached into oblivion, she felt herself doomed.

One day when she was eleven, flipping through Hans Andersen’s fairy tales, she came across the story of the Little Mermaid. The Little Mermaid fell in love with the Prince and would gaze on him from afar. That was romance. That was fine. But then the Little Mermaid yearned to touch the Prince. She wanted him to love her. The price was high. Not only must she leave forever her safe home on the seabed: every step she took in the world of men would be to walk on knives. Lisa shut her eyes and thought of the bone-handled best dinner knives downstairs. Blunt and rounded at the ends they looked harmless enough, but the blades sent a slicing pain through the Little Mermaid. Naturally, it all ended in tears. Lisa resolved to stick to romance, being safer. Nevertheless, the quest for knowledge was strong and when Caro Atkins presented her with a copy of The Love Machine, which had already been round the class, she obediently carried it home in her art folder and spent Saturday reading it. Towards lunchtime her father put his head round the door. Lisa thrust The Love Machine under her pillow.

‘Yes?’ she said, her face hot.

‘What were you reading?’ asked her father.

‘Nothing,’ said Lisa.

‘Don’t fib to me, Lisa.’

‘Nothing important. Really.’

‘If it wasn’t important, you can let me see it.’

‘I’m sorry, but I can’t.’

‘Lisa, give it to me.’

‘Daddy, don’t ask me. Please don’t.’

It was the first time she had ever refused to obey him. He was about to insist but her terror-struck face made him hesitate. She saw him waver and her courage leapt. She was at an age when certain subjects must be left alone. This had never occurred to her before. Her composure returned.

‘It’s nothing, Dad. Honest.’

He retreated in confusion without saying what he wanted.

Lisa stuffed the book into her art folder. She knew this would not be the end.

‘Lisa,’ Edith Brown bustled in a few minutes later, twitching at the creased bedcover; casting an appraising glance at her daughter who was by now seated on the dressing-table stool. ‘Would you run off to Mrs Burridge with the oven timer? Hers is broken.’

‘In a minute, Mother.’

‘Are you all right, dear? Your father thought you looked a bit peaky.’

‘I’m fine.’

‘Was there something you wanted to talk to me about?’

‘No, I don’t think so.’

Edith sighed. She did not encourage girl-talk, but Lisa’s reserve never failed to unnerve her.

Lisa gazed into one of the side mirrors on the kidney-shaped dressing-table, fascinated by the obscure angle it reflected of the underside of Edith’s left breast. ‘As I must have seen it as a baby,’ she thought, shaken. Edith, misconstruing her daughter’s absorbed gaze, thought Lisa was admiring her own reflection.

‘I shouldn’t bother, if I were you,’ she said tartly. ‘It’s always the ugly ones who are the most vain.’

Lisa passed O-levels in English and Geography and left school unsung, her departure barely noticed. Her mother would have liked her to stay on. ‘You ought to have a career,’ was what she actually said, which Lisa mentally interpreted as ‘… because you’re so ugly and stupid no one will want to marry you.’ This was not what Edith meant, but they never discussed it.

In the meantime, Lisa’s father enrolled her at Beckenham Tech for a typing course. And so might her life have proceeded, had Lisa not bumped into Caro Atkins in Chelsea Girl one breezy August afternoon.

‘Beckenham Tech?’ shrieked Caro, clutching a rack of purple shoulder bags which lurched and slithered all over the floor. ‘Bloody hell, Lisa, you can’t go to that dump.’

‘It’s all right,’ said Lisa defensively, without the least idea if it was.

‘What’re you going to do with your life? Bury yourself in some stupid bank for two years and marry an insurance salesman?’

‘My dad’s in insurance.’

‘Come on, Lisa. You’ve got to do better than that. It’s your life. You can’t chuck it away in Beckenham.’

‘It’s only for a bit. Get qualified.’

‘Oh yeah? Then what? Do a modelling course and jet off to Hollywood, I suppose.’

‘Well, you’re so clever. What are you going to do?’

‘Go to London, stupid. You’ve got to go to London before you can even start.’

‘What are you going to do, then?’

‘Typing, of course. Same as you, but classy.’

‘Where?’

‘Oxford Street.’

‘Don’t be daft!’

‘I mean it. After that I’ll get a job in the music business. No problem.’

‘But it’ll cost you.’

‘Cost my dad. But it’s so quick, it saves you money. Pay him back by Christmas out of my salary. How long’s your course?’

‘A year.’

‘God, it’s all rubbish. Bet you do office practice, bookkeeping — all that stuff.’

‘So?’

‘You don’t need it, Lisa. If you do it you’ll get stuck with bleeding books to keep for the rest of your life. Listen, I’m telling you: it takes two months to learn typing and shorthand. Then you can pay your dad back.’

‘What’ll I say? It’s all arranged now.’

‘Just tell him.’

‘He’ll never let me.’

‘That’s okay. Tell him you met someone whose sister went to Beckenham Tech and got VD off one of the teachers.’

‘I can’t say that!’

‘Well it’s true. You ask Susan Harper.’

‘I don’t know her.’

‘Say you do, blockhead.’

‘Did she get VD?’

‘Yeah. Or she got impetigo or something.’

‘I can’t talk to my father about that. He doesn’t even know what VD is.’

‘Come on! Why d’you think they make you put paper on the seats in public toilets?’

‘I can’t talk about something like that.’

‘Bloody hell, Lisa. It’s time you left home, it really is. You can’t be nurse-maiding them forever.’

So it was, remarkably, that on September 30th 1972, two days after her seventeenth birthday, Lisa sat squashed in the corner of a commuter train to Charing Cross.

‘Dear Sir,’ she transcribed painstakingly into speedwriting as the train jogged over Hungerford Bridge. ‘We acknowledge receipt of the chairs. Our repair man knows the height of each leg. When you let us have the new cheque duly signed, we can cash it.’

3. THE PRESENT — JULY 1974

By the time Lisa got home from the hospital it was quarter to ten. She was acutely self-conscious about the ambulance — would much rather have waited for the bus despite her exhaustion — but the staff nurse insisted. Gingerly, she carried Katie up the communal stairs to their flat and into her tiny room which opened off the main bedroom. The curtains were still drawn. The child, her brittle arm bound, slept peacefully.

Lisa went into the sitting room and opened the curtains. Like everything else in the furnished flat, they smelt of other people. Dust and sunshine filled the room, glancing off the sideboard, the electric fire. The flat was above a launderette and Lisa fancied the dust came from the extractor vents of the tumble-dryers (well, at least it would be clean dust, she consoled herself). They had lived there for seven months, but it still seemed as little theirs as the day they moved in. She had worked so hard in those heady days of pregnancy at the start of their life together to make it a home. But the sideboard, the wardrobe and the intractable wallpaper seemed to have eclipsed her efforts. Lisa sighed.

The kitchen sink was full of washing up — the plate from the Wimpy and chips she had brought back from shopping yesterday afternoon, her last meal, she realised; the Ovaltine she had made at one in the morning when Katie was keeping her awake. She felt so tired she almost left them as they were, but the mess filled her with revulsion. First she washed the plate, the cup and scoured the milky saucepan, drying them carefully and wiping down the draining board afterwards. Then she swept the two square yards of floor. As she bent her head she became aware of the familiar throbbing headache which was now a feature of her daily existence. She considered eating, opened the fridge and stared into it; took out an egg and hunted in vain for the butter. She put the egg on to boil, went to the cupboard for bread, forgot what she was looking for and took out a packet of dried figs instead. She ate the egg on its own, leaning against the sink. Then she trailed back into the sitting room, tearing off a fig and chewing it. Lisa curled up on the sofa and fell asleep.

She was woken by a ring at the doorbell. The sun had gone. She was stiff and cold. When she stood up, the packet of figs slithered to the floor. Her head felt heavy and fogged. The doorbell rang again. Lisa answered it. It was the health visitor, Fiona Slater, and a young woman she had never seen before. Lisa stood aside and they both entered. Mrs Slater introduced the other woman as Ann Cartwright.

‘My dear, I’m so sorry about Katie,’ she said, bustling upstairs and into the sitting-room. ‘I’ve had the most terrible day, otherwise I’d have come earlier. I say, you haven’t got a cup of tea on the brew, have you? I’m dropping.’

Lisa went into the kitchen and filled the kettle. The health visitor followed her. Lisa wished she wouldn’t. She was conscious of the egg shell lying on the draining board and threw it away hurriedly. While they waited for the kettle to boil, she rinsed out the egg saucepan and Mrs Slater took a dishcloth.

‘Always neat and tidy, even in a crisis!’ she marvelled.

Something about the way she said this put Lisa on her guard. ‘I’ve been so worried,’ she murmured.

‘Well, Katie’s fine, they say. You’ve nothing to be frightened of.’

‘Who say?’

‘The hospital.’

‘They called you?’

‘Yes, of course they did. How would I have known otherwise? The social work people wanted to make quite sure you weren’t left on your own.’

‘Why?’

‘Why? Well, of course you shouldn’t be alone at a time like this.’

‘But I’m usually alone, with Paul away. I don’t understand why they’re in on this.’

‘Who?’

‘The social workers.’

‘But, Lisa, it’s routine. Why should that worry you? Miss Cartwright is from social services.’

‘That lady in there?’

‘She’s not so very fierce, is she?’

‘Why has she got to come as well as you?’

‘Because that’s how it works. I’m from the clinic. She’s a social worker.’

Lisa thought about this. Then she asked, ‘You sure the baby’s all right?’

‘Oh, you mean you’re afraid they’re keeping something back?’ Lisa stared at her aghast. What would she say next?

‘You poor thing. Don’t gawp at me as if you’ve just seen a ghost. Look, I promise there’s nothing wrong with Katie they haven’t told you about. It was a clean fracture. It’ll mend in no time. It’s just a question of trying to keep her calm and happy.’

‘With this colic she’s never happy.’

‘Now that’s not true, Lisa, and you know it.’

‘You don’t see her when she yells all night.’

The kettle boiled. While she made the tea, Lisa’s tired brain was racing. She liked Mrs Slater, with her breezy self-confidence, but the thought of the social worker filled her with dread. Why was she here? She seemed very young. Was such a woman to be trusted? They carried the tea into the living room.

‘Does your husband know?’ asked the health visitor.

Lisa shook her head. ‘I can’t get through to him during the day. I’ll phone this evening. He’s going to be so upset. Perhaps it’s better he’s away.’

‘If he’d been here,’ Ann Cartwright observed, ‘it probably wouldn’t have happened.’ It was almost the first time she had spoken.

‘What d’you mean?’ Lisa asked.

‘She wouldn’t have been left alone. It must be terrible trying to cope on your own.’ The young woman looked kindly. Lisa considered what she had said.

‘I only left her for a moment to get the nappies. I know I was stupid,’ she admitted, downcast.

‘Not stupid,’ said Ann gently. ‘A bit thoughtless, maybe. But left alone with a colicky baby for weeks on end, there’s bound to be the odd slip.’

‘Did you get the changing mat as I suggested?’ asked Fiona Slater.

Lisa blushed. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘But I had it on the bed.’

‘Changing-mats are useful because you can pop baby on to the floor if you have to leave the room,’ said Fiona. She managed not to make it sound like a reproof.

The talk turned to goats’ milk and strategies for coping with colic. Lisa began to relax and spoke enthusiastically of getting a liquidiser as soon as she could afford one, so as to be able to give Katie fresh food when the time came. Mrs Slater drained her tea.

‘Forgive me rushing off, girls,’ she said, standing up. ‘But I’ve three more visits this afternoon. Can I just tiptoe along and see Katie?’

‘Yes, she’s exhausted, poor little thing. She’s been asleep since we got home.’

In the tiny room off the main bedroom, Katie slept on. Fiona Slater smiled, glanced about her and crept out on to the landing.

‘I’ll drop in on Friday,’ she said. ‘Try to get some sleep before she wakes up.’

Left alone with Ann Cartwright, Lisa felt nervous again. The social worker chatted amiably about Paul’s work and Lisa’s hopes for his homecoming.

‘We’re here if you want us,’ she said. ‘But I’m afraid it may not always be me who comes to see you. I was on duty when the call came.’ It all sounded harmless enough, but then Ann asked, ‘Where do you keep the nappies, by the way?’ So they were going to talk about it.

‘In our bedroom,’ said Lisa, her mouth dry. ‘Last night, when it happened, I’d run out. I came in here because I hadn’t unpacked the shopping. When I got back — well, there she was.’

‘How, exactly?’

‘What?’

‘How was she lying when you got back?’

‘Oh. She was on the floor. It was terrible.’

‘I don’t quite see. You left her in the middle of the bed.’

‘Well, quite near the edge, I suppose.’

‘Has she ever thrown herself about like this before? It’s very strange for such a tiny baby.’

Lisa shook her head. The social worker persisted, ‘Didn’t you think of taking her with you, since she was crying so much in the first place?’

‘Look,’ Lisa said. ‘I couldn’t cook supper. I managed to make some Ovaltine when I did her bottle. But that was all. I had her with me all the time. I was holding her all the time. I knew if I took her with me again it would be slower, and she wasn’t wearing a nappy. You know, it’s been like this for weeks.’

‘Poor you. I must say, I’d find it very difficult to cope. I think I’d feel pretty fed up with the baby.’

Lisa didn’t answer. She guessed Ann Cartwright had no children.

‘Don’t you?’ smiled Ann.

‘Don’t I what?’

‘Get fed up?’

‘Of course I do.’

‘I mean with the baby.’

‘Oh well.’

‘You mustn’t be afraid to admit it.’

‘You can’t blame her,’ said Lisa seriously. ‘She’s only little. She must be in terrible pain to cry like that.’

‘Lisa, it’s nothing to be ashamed of. Many women feel that way.’

‘I don’t know what you mean,’ said Lisa, trembling.

‘We can help you.’

‘I’m fine, I promise.’

‘Are you all right? You look very pale.’

Lisa began to sob. Ann moved across on to the sofa and put an arm round her shoulders. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘I had to put it to you. I didn’t want to upset you like that. But I had to say it, Lisa.’

When she could speak again Lisa stammered, between gulping sobs, ‘I love Katie … I want to be a good mother … And then I leave the room for a moment … And Paul’s not here … And I seem to feel dreadful and exhausted all the time …’

When she was quiet again, Ann went into the kitchen and put more water on the tea. Her face was thoughtful. She poured the tea, spooned two sugars into Lisa’s cup and returned to the sitting room.

Lisa said when Paul came home and started earning better money they would begin to save for a ‘real house.’

‘This is a real house,’ smiled Ann, looking round at the ugly but immaculate room.

‘No,’ cried Lisa, her faced flushed now from crying. ‘You’ll see. One day. It’ll all be all right.’

‘I’m sure it will. Well, I must be going. I’ll have a think about getting more support for you. How d’you feel about joining a group of other mums?’

Lisa pulled a face. ‘I don’t really feel like other mums,’ she said.

‘Oh really? Why’s that, then?’

‘I hurt my baby,’ said Lisa in a little voice. Ann waited.

‘What d’you mean? she asked.

There was a long pause. ‘Because of me,’ Lisa said at last, ‘my baby broke her arm.’

‘How did she break her arm?’

‘She fell off the bed,’ Lisa repeated. Ann saw a pleading in her eyes. ‘I told you. But it was my fault.’

‘Thinking like that will do you no good at all,’ said Ann briskly. ‘You must try not to brood about it. I’ll see what I can do.’

‘Will you come and see me again?’

‘Maybe. Maybe someone else. Here’s a card. Ring this number if you want to talk at any time. Ask for me. Take care.’ And she was gone.