2,77 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

When Hannah Morgan discovers the entire collection of the most famous art theft in the world, she imagines a tranquil journey to Boston to return the collection. What could go wrong? Apparently a lot, as the sinister custodian of the stolen art, and a host of police agencies, feverishly track every step that Hannah takes. What begins as an adventure on the open road soon develops into a test of Hannah's resolve and endurance as she maintains one strategic move ahead of her pursuers, and delivers the collection into an unexpected sanctuary.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 451

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

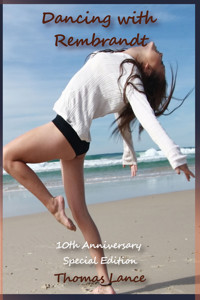

Dancing With Rembrandt

A Novel

Thomas Lance

Dancing With Rembrandt is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination, or are used fictitiously, and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Author Note

Please feel free to visit Facebook.com/DancingWithRembrandt for a gallery of the artwork mentioned in this novel.

Other Works :

The Confession of Alexander Trust

The Refuge

Interstitial

The Road of a Thousand Wonders : Where to Eat, What to See,

Where to Stop on the Road to the Correctional Institution

Journey Number One : The Southern Route to the Snake River Correctional

Institution

PART I

October 29, 2012

Astoria, Oregon

ONE

The grizzled seamen huddled together at the round table in the center of the room, protecting their drinks with weathered hands like the Club Dardanelles sheltered them from the raging storm outside. The club was a dark place, smelling like stale beer, fried food, body odor and broken promises, yet it offered these seasoned men a comforting place of sanctuary. Smoke hung heavy in the air. The music punctuated the room with horns and bass, keeping time for the rhythmic movement of a young woman dancing upon the small stage. Her body was illuminated by searing light, exposing a translucent veneer upon her toned flesh. Clothed only in fantasy, the young woman danced elegantly upon the stage. Black heels met the wooden floor in a hypnotizing cadence. A black bow tie adorned a slender neck, a black ribbon clung to her blonde locks. With each practiced step, the dancer intended to bring the audience tantalizingly close to an imaginary bond with her. An imperceptible movement, or a broad smile, or a seductive wink of the eye hinted a chimerical attachment, if only for a fleeting moment, for she mesmerized her audience into believing the possibility of more than an illusory connection.

“No way anything moves out tonight,” grunted an aging man, hypnotized by the dancer above. He held a pint of ale uneasily in front of his face, struggling to find his parched mouth without taking his eyes off the dancing woman.

“Ain’t nothing leaving for awhile,” said another, “the Bar is just too dangerous with this storm.”

“Where did she learn to dance like that?” inquired another man, enraptured by the twin illusion of unrequited desire and considerate reverence toward the dancer's exhibition of technical precision upon the stage.

“Why would a girl like her ever come to a place like this?” expressed another man, gazing at the young woman tease upon the stage.

“Hannah’s the only reason I come to this dump,” remarked another aging man, watching the dancer. “None of the other gals comes anywhere close.”

“She don’t even use the pole,” remarked the sixth man. “She just glides along, like she’s dancing on the clouds.”

The men occupied the best table in the club, on a platform elevated four inches from the floor, reserved solely for the Columbia River pilots.

The Columbia River Bar, just to the west of Astoria, where the Columbia River propels its current against the tumultuous tide of the Pacific Ocean, has been the graveyard of ships and seamen for well over a century. The sheer volume of the cold waters of the Columbia flowing into the Pacific creates a hellish vortex into which ships venture at their peril, especially during winter storms. The river pilots, whose orders to guide the ships into the river or out into the Pacific, rule the mouth of the Columbia, meeting unquestioned obedience from shippers who depend upon their expertise to guide cargo through the treacherous waters to safety upon the docks.

“Turn that crap off!” yelled a man at the bar, jolting the men clustered around the pilots’ table. “I’m tired of hearing about Superstorm Sandy.”

The man quaffed his drink, slammed his pint on the bar and pointed to the bartender. “When is CNN going to tell the nation about our storm of the century?”

“Shut the hell up, Raymond!” barked one of the river pilots. The longshoremen and the river pilots formed an uneasy alliance on the docks of Astoria. The pilots occupied the superior position, entitling them to deference.

Raymond Tigness, the disgruntled man, wiped his mouth with his sleeve, and nodded with his head toward the bartender, calling for another draught. A dockworker since his youth, he had seen many storms strike the Pacific Coast, but nothing like this one. Now retired, widowed, and increasingly lonely, he hauled his withered body nightly to the Club Dardanelles, seeking some measure of comfort for the emptiness within his aching soul.

“Raymond the Regular will never get it,” whispered one of the pilots to the group. “We don’t matter.” The men smiled at each other, recognizing the truth of both statements.

A man dressed in a fashionable suit, with a red tie pulled askew, wore dark eyeglasses to conceal his presence. He smirked from a corner table. Sitting alone, with a tumbler of seltzer water positioned between an iPhone and a tablet, he had an unobstructed view of the room cluttered with men and women seated at wooden tables arranged so that each patron had a view of the stage. The mysterious man inhaled deeply on his cigarette, watching the young woman dance. He observed the dancer’s unique performance with an eye trained for discipline. ‘Demi-plié,…soutenu en tournant,…piqué turn,…demi-plié,…chaîné turn,’ narrated the man as he watched the young woman effortlessly perform. ‘Toes perfectly pointed, porte-a-bras across the chest, fingers rigid in position,’ he critiqued dispassionately. The elegant synchronicity of the woman’s dance clashed with the stark surroundings of the club. ‘Classical dancer,’ he mused, alone with his thoughts. ‘What kind of tragedy brought her to this place?’

Explosions of laughter and errant chatter burst the imaginings of the mysterious man. At a table to his right sat four young men, dressed in a contemporary urban style who engaged in unrestrained talking. They sent sleazy comments toward the dancer on the stage, accompanied with frenetic, obscene gestures. The men were singular opposites of the river pilots, seated quietly on the elevated position of reverence, silently watching the young woman perform. The younger men pointed in a frenzy, fueled by intoxication, toward the dancer in a manner that signaled to the mysterious observer that these younger men, accustomed to entitlement from the club, were regulars, too.

Suddenly, the iPhone vibrated upon the wooden table in front of the secretive man. He clutched the phone as he arose from his seat. The mysterious man stepped gingerly past the elevated table, evading the younger men, and made his way to quieter surroundings outside.

“As-salaam-alaikum,” he whispered into the device.

The dancer finished her performance to an acknowledgment of polite applause from the pilots at the elevated table, and an eruption of raucous approval from the cadre of young men swarming the corner table. The dancer smiled at the men at the elevated table, avoiding the catcalls of the younger men as she reached for her dressing robe. She glided off-stage, as if she were still in her performance, relieved that her last dance of the night had come to a close. Soon she would cleanse the filth of the Club Dardanelles from her physically and emotionally exhausted body.

“Hannah,” barked a heavy-set woman in her fifties. “I booked you in a VIP room for Mr. Ischii.”

Hannah Morgan caught her breath. Blonde, in her early twenties, with blue eye shadow and powdered face, masking her self-identity with cosmetic artistry, she paraded in the hallway with a robe she quickly pulled around her nakedness. “Not tonight,” she said to the woman, almost begging.

Virginia Hamilton, the capricious owner of the club for nearly three decades, had seen a fair number of dancers of varying degree of ability, and hundreds of dancers with a measure of inability. But Hannah was unique. Hannah quickly became the franchise performer of her establishment, filling the tables on her scheduled performance nights. Virginia recognized from Hannah’s audition that she was a very different performer. Perhaps it was her technical dance training, or her limitless eye contact combined with a seductive smile. Exotic dancers carried wounds and painful experiences, submerging their hurts beneath the flesh they exhibited to paying customers. Somewhere in her past, Hannah had experienced profound anguish, but unlike the other dancers, Hannah subsumed her host of hurts to a distant place where Virginia could not reach. The other dancers had no relationship with Hannah, considering her aloof, superior, or snobbish. And Virginia exploited that detachment to distinguish her reluctant star, Hannah, from the other dancers for pure marketing strategy. Chief among her capitalistic practices were invitations to a VIP Room, a place limited only by imagination.

Virginia spoke harshly to the young woman. “You get in there and entertain Mr. Ischii and his associates!”

“But the storm…”

The older woman grasped the younger one by the arm. “I don’t care about no storm, Hannah.” She squeezed tightly around the arm of the young dancer. “Mr. Ischii and his associates don’t care about no fucking storm, either, Hannah.”

“But…,” Hannah implored

Virginia Hamilton interrupted her dancer. Stepping chest to chest with Hannah, she shouted, “Mr. Ischii is a regular patron, Hannah, and he specifically requested you to entertain him and his associates.”

Hannah bit her lip nervously while twisting out of the firm grip of her supervisor. She reached up to pull a bobby pin attaching the black ribbon in her blonde hair, and pleaded, “I have to go now. Allie is waiting for me. The storm outside…”

Virginia Hamilton approached her, menacingly. “You get one thing straight right now, Hannah Morgan. You work for me!”

“I know,” pleaded Hannah. “The storm…”

The other dancers crowded close to their boss and the reluctant star as the older woman snarled toward her dancer. “You have two choices, honey. You can get in that room and entertain Mr. Ischii, or you can get the hell out of my bar and don’t ever think about coming back!”

Hannah Morgan sighed, resigning herself to the demeaning tasks that awaited her behind the red door. With a trembling lip, she reached for the handle and stepped inside.

Her life was never supposed to be this way. She was born into a solidly middle-class family in Portland. Her father, George, handled the railroad schedules and shipping dockets at Swan Island. Her mother, Helen, taught art and composition at the local high school. Her brother, Tim, seven years older, mostly ignored her, even before departing the stable family home for college. Hannah was a prodigy. She possessed an insatiable appetite for learning. She advanced through school rapidly, owing to a tenacious work ethic and exceptional scholastic abilities. She had advanced several grades due to superior language, comprehension and composition. However, the shy girl had difficulty relating to classroom peers who were a bit older than she.

Hannah studied ballet from the time she was three until a fractured ankle performing the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy ended a promising dance career in her senior year of high school. While recuperating from her injury, Hannah delved into her advanced placement classes with vigor. Under her mother’s guidance, Hannah submitted her senior honors thesis detailing the works of the Dutch painters Johannes Vermeer and Rembrandt van Rijn, which earned her a scholarship to Reed College. For her graduation present, her mother planned a trip to Boston, to a gallery where Helen had once seen a Vermeer and several pieces from Rembrandt. A diagnosis of advanced uterine cancer robbed Helen of the joy she anticipated in sharing the remaining pieces of Rembrandt with her daughter.

Hannah went across town to college beneath the tall oaks at Reed, grateful that only a few miles separated her from Helen. Her youth, relative to the students in her classes, combined with her uneasiness with her mother’s delicate condition, caused Hannah to question her decision to attend college during the first weeks of school. Her measure of uncertainty took a turn for the worse when her parents died in a car accident on Cornelius Pass Road in October. While mired deeply within her profound grief, Hannah watched helplessly as her brother faced disbarment from a prestigious law firm. Those proceedings became a contentious public spectacle, culminating before Christmas Break.

A professor whom she admired for his intelligence, demeanor, and charming disposition, comforted her during the tumultuous period; but he tossed her aside when circumstances changed. While her peers enjoyed themselves in Cabo San Lucas during Spring Break, Hannah slipped away from Reed, searching for a way to make peace in her world. Almost alone, broken in spirit, her esteem shattered despite a significant impersonal negotiable instrument, she went as far west as she could on a tank of gas before reaching Astoria, a community on a peninsula bracketed by the Pacific Ocean, Young’s Bay and the Columbia River. She settled in to the rough town born on the banks of the uncompromising river. She identified with the juxtaposing mixture of grit, beauty, tenacity, splendor, ruggedness, and calm. It was a place where Hannah could make some peace with herself and her choice.

Exactly sixty-two minutes later, Hannah emerged from the VIP room. Her tears competed with the sweat on her cheek and brow.

“Why are you out so soon?” bellowed Virginia.

“An hour,” stated Hannah. “They paid for an hour.”

Virginia Hamilton stalked toward the young woman. “They paid for two.” She pointed her pudgy finger toward the red door. “You get back in there and make me some money!”

“But, the storm…”

“Damn it!” shouted the mercurial owner of the club. “How many times do I have to tell you, honey, I don’t care about no damned storm. Mr. Ischii and his associates don’t care about no storm!”

Customers seated at the tables in the club turned toward the yelling, obese woman. Conversations ceased as the patrons focused their attention toward Virginia and Hannah.

“I told you, Hannah, that my customers have paid for you to entertain them. Now you take your tits and your sweet ass in there and make me some money in that room that Mr. Ischii has paid for!”

“I can’t, Virginia,” pleaded the young woman, clutching her robe tight to her body.

“If you refuse me, Hannah Morgan, don’t bother coming to work tomorrow.”

Hannah pulled her robe more tight around her, steeling the nerve to respond. “So be it,” she stated as she brushed past the woman, making her way to the dressing room.

“Wait!” snapped Virginia, in a tone reserved for intemperate dancers who discounted her orders.

Hannah stopped abruptly in the narrow hallway. Her back faced her employer.

“Where’s my house fee, Hannah!” bellowed Virginia.

Hannah stopped in her tracks.

“You’re not leaving here until I get my cut!”

“I know, Virginia.” Hannah turned to face the older woman, wiping away sweat that concealed her tears.

“Give me my due now!” snarled the woman. “You’re not leaving here until you give me what’s mine!” she snapped.

Embarrassed as much by the one-sided conversation as she was at the means with which she had earned the money, Hannah pulled a wad of green bills from a purse she secreted within the pocket of her robe. She began counting the money as the other dancers milled about, watching with glee.

“Very good, Hannah,” replied the woman, as she showed the young dancer an emerging smile, rewarding her for a hefty commission. The smile soon turned sinister as Virginia snarled, “now you get the hell get out of my club!”

Hannah returned the purse to her robe. She trudged toward the dressing room, ignoring the commotion of ridicule as the other dancers formed a gauntlet along the narrow corridor. Each of the other dancers hurled insults at her. Toward the end of the line, a large dancer blocked her path, making an immovable obstacle to the dressing room. The jeering competitors presented a jealous front at the young woman who was never one of them. They resented her for her charm, her talent, her appearance, and especially her rejection of them and their lifestyle. The other dancers resented the respect paid to her by the men and women who patronized the club. Hannah jostled with the large dancer, under the taunts of the others in the gauntlet. Once inside the dingy room, Hannah steeled her composure, ignoring the continuing insults. She glanced at the clock mounted upon the cobwebbed wall. She was late. She recognized that a shower would just have to wait. Hannah chose instead to concentrate upon a minimum of dressing. She frantically gathered the rest of her clothing and personal items. She stuffed them deep into a bag she hefted over her shoulder. The competitor dancers jeered at her as she pushed her way out of the narrow hallway toward the front of the establishment.

As Hannah raced out into the club, Raymond beckoned her from his stool at the bar.

“I am really late, Raymond,” politely whispered Hannah. “I don’t have time to talk right now.”

“Just a moment,” returned Raymond.

Hannah yielded for the older man out of courtesy. “I really need to leave,” she said, placing her hand upon his shoulder.

Raymond Tigness reached inside his coat pocket, fumbling for something, before withdrawing an envelope and a tootsie pop. “One is for you, Hannah, and the other for Allie.”

Hannah smiled.

Raymond the Regular was a genuinely nice man who seemed to have a polite appreciation of her. “Someday, Hannah, I guarantee you, that you and Allie will live in a place worthy of your beauty and your spirit. This town and this job ain't for you.” He reached for her hand and brought it up to his lips.

Hannah blushed, feeling the warm lips of an innocent kiss from an admirer who appreciated her for more than what she did on the wooden stage.

Suddenly, she felt an anxious electricity that made her hair tingle on the back of her neck. She turned toward the tables to her right, and observed the mysterious man with the olive complexion peering through the dark eyeglasses at her. His riveting gaze made her feel uneasy.

Hannah bent toward Raymond. “Have you ever seen that guy with the eyeshades in here before?” she whispered.

Raymond peeked over the dancer’s shoulder toward the mysterious man.

“Can’t say as I have, Hannah.”

“Neither have I.”

Raymond took the hand of the young woman. “I can walk you out to your car, if you like.”

Hannah smiled. “No, thanks. I’m a big girl now.” She winked at the man as she started to walk away.

“Take care driving home, Hannah,” interrupted Raymond. “The storm of the century is pounding Astoria tonight.”

An immediate sense of dread entered Hannah as she remembered that she no longer had a home.

Raymond read her face, noticing that he had upset her. “Is something wrong?”

Hannah shrugged her shoulders. “My bank accounts were garnished this morning, and Mr. Coombs wouldn’t work with me while I cleared it all up.”

Raymond banged his empty pint on the bar in a fit of disagreement. “That bastard should have never evicted you and Allie,” continued Raymond.

Startled, Hannah emerged from her feeling of disappointment. “How did you know?”

“My little cousin couldn’t handle a man’s job like mine,” Raymond responded. “He had to get his jollies using paper instead of using his hands.”

Hannah nodded, clutching the envelope.

“Evictions are easier than working a real job.”

“I wouldn’t know,” said Hannah. She started to pull away.

“I wondered when that worthless piece of shit would finally pull the trigger on you.” Raymond pointed at the envelope in her hand. “That’s a little something I’ve been saving for a rainy day.

“I can’t accept this, Raymond.”

The man gently took the soft, alluring hand grasping the envelope, and delicately wrapped her fingers around it with his calloused, worn hands. “I insist.” He winked at the young woman. “Just pay me back someday.”

Hannah opened the envelope to find a few green bills secreted within. She smiled at Raymond, as she carefully folded the envelope, and placed it inside her jeans pocket. “Thank-you for thinking about us.”

Raymond pulled her close. “Just get out of here now before Virginia takes her cut.” He winked at the young woman.

Hannah rushed out of the club, peering over her shoulder at the sinister man in dark eyeglasses at the table. As hurried as she was, she nevertheless sensed something evil in his presence.

The wind whipped her 1995 Tempo across Second Street, toward the hills on the south side of town. Rain fell like stones onto the windshield. The wipers furiously attempted to shove aside the remnant. Hannah plied Eighth Street, turning into the teeth of the wind on Franklin, destined for a house just on the corner of Skyline, high atop the hill. The car groaned as it climbed the hill, warring against the awesome wind and the unrelenting rain. At last she reached the house. She silently rejoiced that the porch light still illuminated safety from the storm.

Hannah sprinted across the soaked yard toward the door, hoping that Mrs. Nunez would be reasonable. Before she reached the porch, the door opened to a woman holding a small child by the hand. “You’re late, again, Hannah.”

“I’m really sorry, Mrs. Nunez. I was late at work.”

Mrs. Nunez frowned. “Your work is so demanding, isn’t it?” she asked arrogantly.

“I know I’m late,” pleaded the young woman. “It won’t happen again.”

Mrs. Nunez laughed. “How many times have I heard that line?”

Hannah shrugged her shoulders. “Please, Mrs. Nunez. Just another chance?”

“Don’t bring her back,” interjected the woman, cutting off any effort to reconcile.

The little child standing next to Mrs. Nunez wiped her eyes. Her sleepiness obscured any awareness of the situation.

Mrs. Nunez pushed the sleeping child to Hannah. “I really hope you get yourself together someday Hannah, if only for Allie’s sake.” She pulled a bag from the doorway and tossed it on the porch in front of the young mother before slamming the door and shutting off the porch light. The door closing in her face gave Hannah yet another reason with yet another person to reject her, all serving to make her feel as worthless and rotten as the salmon carcasses littering Young’s Bay with a smell of putrid failure. She clasped the little child tightly against her, and whispered in her ear, “we’re going be alright, Allie. It’s just me and you again.”

Alexandra Grace Morgan was almost five years of age. Tall, slender with auburn locks curling around her ears and brow, she had her mother’s delicate features, calm disposition, and prodigious intellectual attributes. She was extremely shy, talkative only when feeling a sense of comfort in her surroundings, or incipient hunger. She used language sprinkled with proper grammar and syntax, coaxed by her mother. She loved to draw and to make pictures, which Hannah had eagerly conveyed to Raymond, the child’s most ardent admirer.

“Come on, Allie, we have to make a run for it.” Hannah grabbed the bag in one hand, and pulled her coat over her daughter with the other, with the skill and dexterity that only a mother could muster. She raced through the pelting raindrops to her car that idled roughly in the driveway. With the raindrops soaking her skin as she placed her daughter in the car seat, Hannah ignored the howling wind whipping the trees along the roadway as she fastened the clips. She hastened into the driver seat.

“My bed is gonna be warm and comfy tonight.”

Hannah bit her lip, grateful that negotiating a turn produced a spontaneous distraction from responding to her child.

“Will you finish showing me A Ball for Daisy?”

Holding the Ford in the lane as the wind furiously buffeted it produced another spontaneous reason to not respond.

“I like the pictures in A Ball for Daisy.”

“Me, too.”

“Will you show me the pictures when we get home, mommy?”

“No, Allie,” she replied softly. Hannah decided that tonight was not the night to let her daughter know that they no longer had a home. “We’re not going home tonight.”

“Why?”

“We are going stay in a new place, out by the river, so we can watch the storm.”

“Good,” piped Allie. “I like storms.”

“Me, too, honey,” agreed Hannah. She pulled out the tootsie pop. “Raymond says hi.” She handed the tootsie pop into her daughter's eager hands.

As Hannah reached a narrow turn, she bit her lip anxiously, piloting the old Ford down the hill, toward the vast river stretching below. Buffeted by howling wind and blinding rain, Hannah drove slowly toward an old hotel she remembered near Tongue Point. She had stayed there for her first week in Astoria, sketching out a plan for how she would spend her new life caring for herself and another. She recalled that the hotel was old and dingy, but it now promised a comforting refuge that she and Allie needed to ride out the storm, as well as a repeat opportunity to sketch out another life plan. “Plus ça change,” she whispered.

“You’re talking funny again, mommy.”

“Someday I’ll teach you French, and you’ll understand me.”

“I will never understand you, mommy.”

“Why?”

“Because then I will talk funny.”

The young mother smiled, grateful for the conversation, for it took her mind off of the impending homelessness that competed with other negative consequences torturing her and Allie in their immediate futures.

Hannah reached Lawrence Avenue, a shortcut to the hotel along warehouses and wharves interconnected with dense forests. The rain and wind seemed to diminish to a point that Hannah started to relax. “We’re going to be fine,” she muttered, giving herself courage to surmount the storm.

“Are we there yet?” sprang a voice from the back seat.

Hannah smiled. “Almost.”

Suddenly, Hannah heard a cracking noise, and a rush of wind unlike any of the sounds that the storm had produced. From the headlights shining forward from the old Ford, she saw branches of a gigantic tree rushing toward her in an unavoidable burst of speed. Hannah shrieked as she pounded on the brakes to avert the tree. She watched in horror as a branch fell in slow motion, landing upon the hood of her car. She screamed when the branch impacted the vehicle, watching helplessly as the agonizing slow motion tumult of the branch crushed the hood, bringing the car to a bone-shattering stop. Her head marched forward in an inalterable course toward the steering wheel.

Hannah awoke, not knowing if moments or hours had passed. She rubbed her head from the impact with the steering wheel. She remembered her passenger in the back seat.

“Allie, are you hurt?” she called out.

Only silence emerged from the back seat of the crushed car.

“Allie! Allie! Allie!” Ignoring her throbbing head, Hannah screamed as she struggled to rip off her seat belt. A large branch had penetrated the passenger cabin. Wooden shards, tiny glass fragments, and small branches littered the front passenger seat. She grasped through the leaves, shouting at Allie in the back seat, while desperately grabbing at what remained of the front seat in an effort to find her cellphone. Her fingers grappled with something familiar as she slowly recognized that her cellphone had shattered from the impact with a tributary branch. She screamed in the direction of the back seat. Hannah extricated herself from the seatbelt. She examined the back seat, and saw her daughter, sound asleep, spared from any injury.

The wind began to howl again. The trees swung precariously in the wind. The rain began pouring from the sky. Singularly focused upon finding shelter for Allie, Hannah awkwardly groped through the darkness to unfasten the child restraints, keeping constant watch of the fury surrounding her from the raging wind and torrential rain. Her head throbbed. Her knee was sore from contact with the dashboard. She stuffed her pain away as she pulled her daughter to her chest. She ran through the trees that whipped helplessly overhead from the wind. She listened to the cacophony of the wind and feared the unpredictability of the next tree falling. Hannah looked around as she wrapped her coat around her child, seeking a house or a barn or a light signaling a refuge from the storm. Off in the distance, near the river, a shimmering light flickered through the tree branches waving in the wind. Hannah followed the light, noticing a gravel road that led to a warehouse on a pier. She detected that an enormous tree branch had sheared off part of the wall of the warehouse and had ripped a gate in its wake. The gate pounded a post in the torment of the wind. Razor wire danced like silvery serpents in the tempestuous wind, but Hannah determined to make her way toward the warehouse, optimistic that she would avoid the sharp prongs of the wires. She carried Allie through the wind and the rain to the hole in the wall of the warehouse. She steadied herself on the branch that penetrated the building, then pulled herself and her child inside the warehouse.

Darkness engulfed the two intruders. The wind outside muted to a forbidding echo. Hannah followed a route through a series of doors that led through the dark warehouse. She came upon an open door to a room that she guessed was a break room or a kitchen. She shut the door behind her and her daughter, and made a path to the refrigerator in the room. “Are you hungry?” she asked Allie.

“Yes,” she said, putting the tootsie pop in her pocket.

Hannah rummaged around the refrigerator and found a sandwich, some cheese, a package of yoghurt and some bottled water on the top shelf. She didn’t bother examining the lower shelves. Hannah pulled Allie to a seat at the table in the little room. “Let’s eat and then we will go to sleep, because it is very late, Allie.”

“Ok,” replied Allie.

Hannah looked around the room. She found a cabinet that held some silverware in plastic trays. Next, she spied a flashlight laying on a counter, next to the cabinet. She noticed some coats hanging on hooks on a panel across from the silverware cabinet.

“Let’s put this coat on you.”

“No, mommy. I want my coat.”

“This coat is fine, Allie.”

“But I want my coat.”

“Allie, this coat will dry you off, so you can get warm.”

“My coat makes me warmer.”

Arguing with her daughter was pointless. She decided to invoke a sympathy theorem. “If mommy goes outside to get your coat, the wind will blow mommy away.”

“But it didn’t blow you away when you runned in here.”

“Ran, Allie. I ran in here.”

“You didn’t blow away when you ran in here,” corrected her child.

“But I was carrying you, Allie.”

Allie appeared convinced. She reached for the coat in Hannah’s hand.

“I’m going to look around here to see if I can find us a place to sleep.” Hannah placed the food and silverware in front of her child.

“But, what about eating?”

Hannah pulled the top off of the yoghurt. “You start eating, and I’ll come right back.”

“I will leave you some, mommy.”

Hannah ran her fingers delicately through Allie's hair. “You stay here, Allie, while I look around.” Allie nodded as she eagerly ate the yoghurt. Hannah went out of the room to explore. Next to the kitchen, Hannah entered a room with a window facing the river. She surmised that the room belonged to the supervisor of the building, judging from a large wooden table, file cabinets, lamps, and piles of documents stacked in a method known only to the person who sat at that particular desk. To her delight, she discovered a sofa in a corner of the room, across from a heavy wooden desk.

This room, and its condition, reminded her of her father’s office in a shipping warehouse on Swan Island. She recalled accompanying her father to work when she was a little girl. He had always made her feel special as she carried maps and files and documents around his office. But times had changed.

Hannah returned to the kitchen. Finding Allie finishing her sandwich, she wiped the crumbs from her face, and stroked her hair. “I found us a place to sleep, Allie. Follow me.”

“But, Mommy,” exclaimed her child, “I have to brush my teeth.”

Hannah smiled. “We will get the toothbrushes from the car tomorrow, Allie.”

“But I don’t want tooth decay, mommy.” Allie stomped her foot on the linoleum tile covering the floor. “I want my toothbrush!”

A stand-off in the middle of the night, during a ferocious storm, with a tired child, did not enthuse Hannah. Instead of an argument, Hannah took a deep breath, and calculated a new angle. She strolled calmly to the refrigerator. As she opened the door, she glanced at the disputatious child. “I think I saw some tooth decay preventer in this refrigerator, Allie.”

“But I want my toothbrush.”

Hannah perused the Tupperware containers, bottles of catsup, containers of pickles and a few moldy items in some plastic buckets and casks. She made a point of making as much noise as possible, clinking bottles and clacking containers. She peered at her child, now silently watching her fumble through the refrigerator. “Just what I was looking for,” said Hannah with a smile. “A little bottle of tooth decay preventer.” She showed the bottle to Allie. “Now, all I need is a spoon.”

Allie leapt toward a cabinet. “I saw one in here,” she said, as she pulled one open to reveal the small collection of silverware.

“Shall we take this one?” asked Hannah, pulling out a small spoon.

“No, mommy,” argued the child. “I want this one.” She held aloft a tablespoon.

“Is it going to fit?”

Allie shook her head. “You always say I have a big mouth, mommy.”

Hannah stifled a laugh, not wanting to destroy the illusion of seriousness. “That big spoon will do nicely, Allie. This medicine will chase away a lot of tooth decay.”

Allie suddenly changed her attitude. With a beaming smile, she whispered, “you’re funny.”

Hannah carried the bottle to the drawer from which the spoon had emerged. She rustled through the silverware, making as much noise as she could, in search of the perfect implement.

“What kind of medicine is that, mommy?”

Hannah pulled out a metal apparatus, continuing to make as much noise as possible, and attached it to the cap of the bottle. “This medicine is called ale.”

“That’s a funny name.”

“I know, honey, but it’s a short name for a fermented beverage containing hops that conquers tooth decay.”

“That’s a long name.”

“Which is why we call it ale.” Hannah set the opener underneath the cap. When she pulled, the cap exploded off the bottle, producing a stream of frothy liquid lurching from the opening.

Allie squealed with delight. “That medicine makes bubbles!”

Hannah smiled. “That’s what scrubs off the tooth decay, honey.” She poured a tablespoon for her daughter. “Now drink some of this medicine. It will scrub your teeth, and help you to sleep.” She watched Allie contort her face as the cold liquid rolled in her mouth.

Hannah brought the bottle directly to her lips, drawing in a gulp of the ale. The cool bubbles soothed her mouth. She felt the cold droplets course along her tongue and down her throat.

“Why don’t you use the spoon?” interrupted Allie, jolting Hannah from the sensation of the ale.

“My mouth is bigger than your mouth, sweetie.”

Allie rubbed her eyes. “I’m ready for bed.”

“Me, too.”

Hannah held on to the bottle of ale in one hand, and took her child by the other hand, leading her to the sofa in the supervisor’s room next door. She lay her child on the sofa, and covered her with some coats that she took from the rack.

“Go to sleep, Allie.” She stroked the forehead of her daughter while humming a lullaby until sleep quickly overtook her child. She listened to the gentle rhythmic humming of her daughter’s breath, continuing to stroke Allie’s forehead. Tiny sips of ale grew into large gulps of ale as Hannah desperately sought some temporary relief. The ale brought some respite, blurring for a moment the haunting memories of the last twenty-four hours.

Garnished bank accounts to start her day.

Eviction from her apartment.

Leaving her child with a sitter while she exposed her body to paying strangers.

Dancing for drunken men and women, catering to their fantasies.

Driving in a storm, narrowly averting a disastrous wreck as a falling tree demolished her car.

And, now, sleeping in a warehouse that was damaged by storm.

Today was only an accelerated microcosm of her current life, comprising nothing of what she had ever intended. How did this happen? Why did this happen? Would it ever change?

The effects of the ale began to wear off, bringing Hannah to tears as she reflected upon the immediacy of her life, compounded by the immeasurable responsibility her child presented each day.

The first moment that Hannah held her precious child, nearly five years earlier, she had determined to make each day a better one for Allie than the day before. She had focused her ambition on creating a normal life for her daughter. She ignored any thought for herself as she pursued mere survival. Shame evaporated when her eyes met those of her child at the end of each day upon the stage. Allie’s existence produced in Hannah a sense of purpose and a glimmer of hope for a brighter future.

But today had been difficult. Peering around the vacant room, listening to the gale and rainfall, Hannah reflected on the sheer multitude of things that had misplayed. The gentle purr of Allie’s rhythmic breathing clashed with the dangerous circumstances surrounding them. The wind pummeled the warehouse with an invisible hand of power so severe that the boards groaned to keep the roof attached. The tree limbs whipped in an airborne frenzy like serpents. The rain fell in such quantity that the gutters immediately dislodged the water over the rim. As Hannah reflected upon the events of the day, she could not help but view herself as a magnificent failure. Homeless. Broke. Unemployed. Scared, in a warehouse, surrounded by tempest and gale.

At last sleep overwhelmed her tears.

Hannah awoke from her slumber. She heard the storm raging on outside. The trees whistled in the penetrating wind. The gate pummeled against the metal post in the gale. Competing with the wind, however, emerged a soothing sound of a ‘scritch-scratch’ of pencil upon paper. She smiled, seeing that Allie had found a way to occupy herself.

“Good morning, Allie.”

Her daughter did not look up from drawing. “Good morning to you, too.”

Hannah rubbed her eyes, accustoming her vision to the percipient light of dawn entering from the window. “How long have you been awake?”

“A long time.”

Hannah rubbed her temples, trying to summon the energy to arise from the sofa. Instead, she pulled the coats around her as she reclined deeper into the cushions of the sofa. “What are you doing?” she asked, as she massaged her throbbing temple.

Allie lifted her head to respond. “I am coloring a picture for Raymond.” A set of keys on a necklace tapped the desk as Allie wavered on the chair.

“Can I see it?”

Allie climbed off of the chair, bringing a sheet of paper. In her other hand, she dragged something that made a gentle murmur upon the carpet. “Look, mommy.” She handed the sheet of paper to her mother. “Will Raymond like it?”

Hannah squinted her bloodshot eyes to view the picture of a boat sailing on a smooth sea, next to an island with a tree on it, underneath a smiling sun illuminating the island.

“I want to make the boat have a nice day, not like this boat.” Allie handed a large, flat object wrapped in a transparent envelope to her mother.

Hannah felt what appeared to be a canvass with rough edges. She slowly examined the canvass. The image revealed a painting of a boat teetering on its keel. Dark, ominous clouds surrounded the vessel with only a patch of clear sky, a hint of peace, coming from a small corner of the canvass. The tempestuous sea pelted the boat, producing anguished expressions of fear and doubt upon the men. The torment depicted upon their faces suggested an individualized response to the natural forces of the storm surrounding them. Hannah caught her breath. Her fingers trembled as she touched the rough edges of the canvass. She dabbed away moistness on her cheek with her sleeve.

“Mommy,” began the child, “why are you crying?”

Hannah wiped the tear, yet the emotional response she perceived from the painting produced many others.

“Why are you crying, mommy?” repeated Allie, clearly troubled by the strong reaction.

“It’s so beautiful, Allie,” managed Hannah, still transfixed at the painting in her hands.

“No, mommy,” she stammered. “It’s scary, mommy.” Allie hesitated. “The storm in that picture is scary.”

Hannah stared at the painting, half-listening to her child, slowly counting the members of the crew on board the boat. Allie soon joined her, patiently imitating, “…eleven, twelve, thirteen, fourteen.”

“Fourteen what?” asked Allie.

Hannah glanced toward the inscription on the rudder. She recognized it instantly. A misty column of tears slowly glided down her cheek.

“Fourteen what?” repeated Allie. “Why are you crying?”

Hannah struggled to regain her composure. After a moment, she collected herself to offer an explanation that a perspicacious nearly five-year old would understand. “Allie, this is a painting of the most famous storm in the world. There are twelve fishermen in this boat. They are the ones who are scared. Do you see them?” She placed the painting upon the desk. “Step on this chair, and look at them.”

Allie climbed upon the chair and peered at the painting. She pointed at one of the figures in the boat. “That man is sick.”

“Yes,” said Hannah. “Look at the other men. What do you see?”

“All of them are afraid, except this man.” She pointed toward the center of the boat, where a man with a glowing sheen around his face appeared to sleep. His face, relaxed and confident, contrasted from the anguish depicted upon the others.

“He is the leader of the group,” explained Hannah.

“This man holding the rope isn’t scared, either, mommy.” Allie pointed toward the figure in the middle of the boat, looking directly toward her.

“That is the artist who painted this piece.”

Allie studied the scene. “What’s his name?”

“The artist?”

“Yes, mommy.”

“His name is Rembrandt van Rijn.” She omitted the middle name for convenience.

Allie giggled. “That’s a funny name.”

Hannah smiled, agreeing completely with her daughter.

“Allie,” she managed with all the calmness she could muster, “where did you find this painting?”

“In a room out there.” Her child pointed out of the supervisor room.

“Where, exactly, did you find this painting?”

“In a silver box, next to a truck.”

Hannah quivered. “Can you take me to see the silver box?”

“I’m not finished with my picture.”

Hannah carefully smoothed out the transparent envelope that contained the canvass. She caught her breath. “Allie, this is really important. Will you please take me to see the silver box?”

Allie stopped scribbling on her paper. “Ok, mommy.” She put her pencil down. “I will show you a picture with some horsies, too.”

“You mean horses,” corrected Hannah.

“Horses,” repeated Allie. She took her mother’s outstretched hand. “I will show you a picture of a man wearing a funny hat, and another man with a hat like Raymond wears.”

Hannah took a deep breath, preparing herself for what lay ahead. She gently grasped her child’s hand, allowing her daughter to lead through a labyrinthine path toward the central part of the warehouse. As they passed the tree penetrating the warehouse wall, Hannah pulled her sweater tightly around her, eschewing the bitter cold. The sound of wind and rain outside reminded Hannah of the danger they had faced during the night. Allie led her through a sliding door that yielded a room next to the dock. Standing in front of them was a shipping container, a Ford minivan, and a silver box with four wheels. The box, constructed from metal, had a series of compartments with drawers that slid inside. On the top was a handle.

Hannah approached the box, afraid to touch it. She walked around the box, examining it closely. She noticed that most of the compartments were opened. “Allie, did you open any of the pieces of this box?”

Her daughter nodded her head. “All of them, except the one on the very top because I can’t reach it.”

“What did you find?”

“Lots of pictures.”

Hannah gasped as she looked into the interior compartment of the Ford van. Allie had scattered a few paintings on the seat and on the floorboard.

Allie held up a canvass. “This funny picture has a man sitting down next to two funny ladies,” Allie exclaimed.

Hannah caught her breath. “The Vermeer,” she whispered.

“What’s that funny man doing with those ladies, mommy?”

Hannah recovered slightly. “Some people say he is playing the piano, and some people believe he is toying with the two sisters.” She continued absorbing the detail of the painting.

“Why is the man playing with those ladies like a toy?”

Hannah quickly chose to change the subject. “Did you find other things?”

Allie Morgan scratched her head. “I found lots of pictures.” She wandered to the opened door of the Ford van. Hannah observed her daughter pick up a canvass. “Here is one with a man on a horse following another man on a horse.”

“La Sortie de Pesage,” whispered Hannah.

“What?” asked Allie, paying attention to the different language her mother spoke.

“It’s a painting about a racehorse,” answered Hannah.

Allie examined the detail of the drawing. “Why is that man riding the horse into that house, mommy?”

Hannah smiled. “It’s not a house, honey. It is a race track.”

“Oh,” answered her child, innocently. “Like when Raymond goes to Portland to play the ponies?”

“How did you learn about that?”

“Raymond is my friend,” she exclaimed. “Raymond told me he goes to win, place and show with the ponies in Portland.”

Hannah paused, thinking of a retort, but dismissing the only one that immediately came to mind.

Allie returned to the van, placing the first canvass on the floorboard of the back seat, and retrieving another canvass. “I found this picture with a man wearing a funny hat,” continued Allie. She giggled as she pointed to the pipe stove hat.

“Chez Tortoni,” whispered Hannah again, expressing astonishment that she was near to a painting that the world had not seen in two decades.

“Mommy, you’re talking funny again,” teased her child. She toddled toward the box, opened a drawer, and pulled out a pen-and-ink rendering. “Here is my favorite,” she proudly exclaimed, as she held a small drawing above her head. “This funny man has a hat like Raymond.”

Hannah almost fell backward from the breathtaking vision. “The self-portrait of Rembrandt,” she gasped.

“The man in the boat?” asked Allie, whose perception clearly surprised Hannah.

“Yes, Allie,” said Hannah. “It’s Rembrandt again.”

“The boat didn’t sink?”

For a moment, Hannah analyzed the question. “No, Allie, the boat didn’t sink.”

“Good, because storms are scary and Rembrandt is funny.”

Hannah examined the silver box and the paintings that Allie had scattered around the Ford. “Did you take any more of these paintings out of the box?”

“Yes, Mommy. I looked at them, but I didn’t like them.”

Hannah held her breath, concerned with a nagging fear of a possibility of damage.

“I taked them out of the box because I wanted to see them.”

“Took, Allie.”

“Ok, mommy, I took the pictures out of the box.”

“Did you take any of the paintings to any other room in this building?”

“No, mommy.”

Hannah exhaled a breath. Her relief began to grow. “Let’s put all of the paintings back into the box.”

“Ok, mommy.” Flashing an innocent grin, her child pulled each painting together from the Ford, and ran to her mother.

“Somebody lost these pictures,” ventured Allie, as she helped her mother arrange the paintings back into their designated slots within the silver transport box. Hannah locked the items inside their designated spaces within the box. She put the necklace around her neck, and pushed the keys between her shirt and her skin.

Hannah nodded. “Many years ago, some very bad men took these art pieces away from a beautiful building. The good people in the beautiful building were so sad when they found out that the bad people had taken the paintings, that they cried for days and days and days.”

“That’s sad, mommy. Those bad people make me want to cry, too.”

Hannah tussled her child’s hair.

“The people in the beautiful building are still sad that they do not have these beautiful paintings.”

Hannah noticed that one of the paintings lay on a work table. She picked it up, and brought it to Allie, who stood next to the transport box. Hannah removed the keychain necklace from her neck. She placed the key inside the empty storage spot. She pointed to the canvass by Vermeer. “Your grandma, Helen, saw this painting before I was born, Allie. She told me about the beautiful building and the beautiful paintings she had seen there.” Hannah paused while deeply examining the painting. “The bad men took this beautiful painting and others away from the building and hid them in a secret place.”

“Like, in this box?”

“No, Allie,” replied Hannah. “The bad men hid these paintings somewhere, and it looks like the bad men are moving the paintings to another hiding place.”

Allie watched her mother, trying to understand the emotional response she showed.

“Your grandma Helen would be so happy today if she knew that you were the one who found these beautiful paintings.”

Allie Morgan looked at her mother, then looked at the box, then returned her gaze to her mother. Hannah could tell that the child pondered something. “Mommy,” she started, “we gotta take these pictures back to the beautiful building so the good people will be happy.”

Hannah hesitated. “The good people will be very happy to see these paintings again.” She felt uneasy, wondering how she could possibly breathe life to Allie's thought.

Suddenly, Hannah felt a shard of chilling fear pierce her. Somebody, somewhere, would soon return to the warehouse. Their temporary sanctuary existed no longer.

Hannah carefully constructed a plan to rescue the collection from the dockside warehouse. ‘It’s not theft’ she wrestled with herself, as she pondered taking possession of the most famous collection in the world. After all, she convinced herself, the actual crime occurred before the advent of the laptop computer, the fliptop cell phone, and the iPod. The consequences of leaving the collection in the warehouse prolonged the crime and denied the world the opportunity to view the wonderful art. She considered that if she took the paintings, she was not actually engaged in theft because the items had already been stolen by force more than twenty years earlier. She settled upon the concept that she was only restoring the collection to its rightful owner.

Hannah glanced out the window at her car, crushed underneath the enormous tree. ‘Somebody is going to know we were here,’ she reflected, hoping that Allie would not read her uneasiness. She studied her beautiful child before making an intentional decision –- she would return the collection to Boston, to restore the collection to the good people at the Gardner.

An unanticipated recognition suddenly seized her, paralyzing her thoughts. ‘Who would believe a loser like me?’ she asked herself, calculating the reaction of a richly cultivated international art community. ‘I’m dirty,’ she thought, abruptly.

“How do we put the box in the little truck?” called out Allie, interrupting Hannah’s dejection. She glanced at her child, shorter in stature than the silver box she attempted to push toward the Ford van. Hannah battled her self-doubt. Her mind quickly shifted to unsullied acquaintances who might assist in the restoration project.

“Let me have a minute to look at that van, Allie.”

Hannah walked to the Ford van and began an inspection. She opened the glove compartment. Inside lay a black handgun. She quickly pulled the weapon out of the glove compartment and shoved it in the back of her pants. The cool metal against her back sent shivers down her spine. 'I can’t let Allie see this,' she thought. She found no title document for the van. When she glanced toward the rear window, hearing a sound that came from Allie striking the rear of the van with the transport box, she saw a temporary registration sticker with the word ‘diplomat’ attached on the rear window. She resumed her search. Hannah saw a large black bag, similar to the trial briefcase she had bought her brother, on the floorboard next to the driver seat. She pushed the clasps on the bag, which emitted a metallic ‘pop’ that echoed throughout the warehouse. Hannah gasped. Many denominations of green currency lay arranged in neat piles within the bag. Upon the largest pile of currency sat the keys to the vehicle.

Hannah looked out the window of the warehouse. The dawn rays of the obscured sunlight had escaped from the billowing darkness of the subsiding storm. Time, she concluded, worked against her.

“Allie,” she said calmly, “let’s put that box back in the van now.” The two of them gathered two ramps placed haphazardly against the door of the container. The ramps inserted into specially mounted gaps in the bumper of the van.

“Let’s push together, Allie. We can do it,” she urged, as the two of them strained to push the heavy box up the ramps.

“We did it, mommy,” exclaimed Allie, proudly gesturing at the box, as she struggled to regain her breath.

Hannah smiled as she tied the box with strapping rope against the rails of the van to secure the box on its transport. She walked Allie to the rear seat.

“Where’s my car seat?” asked Allie.

Hannah groaned, remembering the seat still remained inside the crushed Tempo underneath the tree outside.