Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

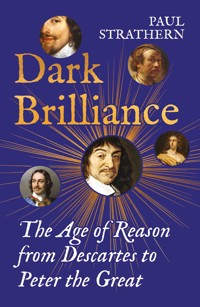

A sweeping history of the Age of Reason, which shows how, although it was a time of progress in many areas, it was also an era of brutality and intolerance, by the author of The Borgias and The Florentines. During the 1600s, between the end of the Renaissance and the start of the Enlightenment, Europe lived through an era known as the Age of Reason. This was a revolutionary period which saw great advances in areas such as art, science, philosophy, political theory and economics. However, all this was accomplished against a background of extreme political turbulence and irrational behaviour on a continental scale in the form of internal conflicts and international wars. Indeed, the Age of Reason itself was born at the same time as the Thirty Years' War, which would devastate central Europe to an extent that would not be seen again until the twentieth century. The period also saw the development of European empires across world and a lucrative new transatlantic commerce began, which brought transformative riches to western European society. However, there was a dark underside to this brilliant wealth: it was dependent upon mass slavery. By exploring all the key events and bringing to life some of the most influential characters of the era, including Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Newton, Descartes, Spinoza, Louis XIV and Charles I, Paul Strathern tells the story of this paradoxical age, while also counting the human cost of imposing the progress and modernity upon which the Western world was built.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 666

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DARK BRILLIANCE

Also by Paul Strathern

The Other Renaissance

The Florentines

The Borgias

Death in Florence

Spirit of Venice

The Artist, the Philosopher and the Warrior

Napoleon in Egypt

The Medici

First published in Great Britain in 2024 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2025 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Paul Strathern, 2024

The moral right of Paul Strathern to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978-1-83895-857-2

Design and typsetting by Carrdesignstudio.com

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To my sister Anne

CONTENTS

Significant Dates During the Age of Reason

Dramatis Personae

Prologue

1 Reason and Rationale

2 Two Italian Artists

3 Spread of the Scientific Revolution

4 The English Civil War and Thomas Hobbes

5 The New World and the Golden Age of Spain

6 Two Transcendent Artists

7 The Money Men and the Markets

8 Two Artists of the Dutch Golden Age

9 The Sun King and Versailles

10 England Comes of Age

11 A Quiet City in South Holland

12 Exploration

13 A Courtly Interlude

14 Spinoza and Locke

15 The Survival and Spread of the Continent of Reason

16 New Realities

17 Logic Personified

18 On the Shoulders of Giants

Epilogue

Notes

Acknowledgements

Illustrations

Index

SIGNIFICANT DATES DURING THE AGE OF REASON

1600

English East India Company founded

1601

Death of Tycho Brahe in Prague; his observations are used by Johannes Kepler to establish the elliptical orbits of the planets

1602

Dutch East India Company (VOC) founded

1603

Death of Elizabeth I after ruling for forty-four years

1606

Willem Janszoon becomes the first European to set foot in Australia

1618–48

Thirty Years’ War

1620

Pilgrim Fathers arrive in North America

1628

William Harvey publishes work on the circulation of the blood

1642

Blaise Pascal invents the adding machine

1642

Outbreak of the English Civil War

1643

Evangelista Torricelli invents the barometer

1650

René Descartes dies in Stockholm

1651

Thomas Hobbes publishes his

Leviathan

1654

Queen Christina abdicates from the throne of Sweden

1665

Great Plague of London

1665

Death of Philip IV of Spain

1666

Great Fire of London

1669

Death of Rembrandt

1671

Gottfried Leibniz invents the calculating machine

1672

Lynching of the De Witt brothers

1673

Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette sail the upper reaches of the Mississippi

1674

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek discovers the microverse

1687

Isaac Newton publishes his

Principia

1703

Peter the Great founds St Petersburg

1715

Death of Louis XIV after a reign of seventy-two years

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Aristotle: Ancient Greek philosopher, lived during the fourth century bc. Much of his (often erroneous) philosophy persisted through the medieval era and beyond, because it was sanctioned by the Roman Catholic Church.

Ashley Cooper, Anthony (Lord Shaftesbury): Powerful political figure in seventeenth-century England, who acted as a benefactor for John Locke.

Aubrey, John: His gossipy but revealing Brief Lives carries much informal information about his seventeenth-century English contemporaries.

Bacon, Francis: A great mind, far ahead of his time, who championed an experimental approach to science.

Becher, Johann: German-born intellectual. His mind was a curious blend of genius and conman.

Boyle, Robert: Anglo-Irish scientist, whose experimental approach meant he is recognized by many as the founder of modern chemistry.

Brahe, Tycho: Danish astronomer, renowned for his vast practical knowledge of the stars, all obtained with the naked eye.

Bruno, Giordano: Visionary scientist and philosopher who was burned at the stake by the Church for promulgating ‘heretical ideas’.

Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi da: Brilliant Italian artist in the chiaroscuro style, whose turbulent lifestyle led him to murder and eventually be murdered.

Cardinal Mazarin: Powerful political figure and diplomat during the reign of Louis XIV.

Castiglione, Baldassare: Wrote The Courtier, a book outlining the etiquette and manners recommended for courtiers.

Cervantes, Miguel de: Spanish author of Don Quixote.

Charles I, King of England: Deposed by parliament, lost the ensuing Civil War and was then beheaded.

Christina, Queen: Powerful, intellectual and wilful queen of Sweden, who renounced her throne.

Colbert, Jean-Baptiste: First minister of France during the reign of Louis XIV. Encouraged the arts and sciences – especially Huygens.

Copernicus, Nicolaus: Polish priest and astronomer who posited the solar system, i.e. claiming that the earth was not the centre of the universe as decreed by the Church.

Cromwell, Oliver: A leader of the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War, who eventually became ruler of England.

Cruz, Juana Inés de la: Extraordinarily talented woman whose talents and intellect were largely overlooked, as she lived in Mexico.

Descartes, René: Regarded by many as the first modern philosopher. Also a supremely talented scientist and mathematician.

Dryden, John: Gifted poet who was forced to compromise as England switched between Catholic and Protestant rule.

El Greco: Greek-born artist who came to prominence in Spain. His ‘distorted’ figures are now seen as wonders of spiritual expression.

Elizabeth I, daughter of Henry VIII: Became queen of England during its great but turbulent emergence as a European power.

Euclid: Ancient Greek mathematician from Alexandria, whose work

Elements, written around 300 bc, influenced mathematicians throughout Europe.

Ferdinand II & III: Holy Roman Emperors, amongst the most powerful rulers in Europe.

Fermat, Pierre de: French mathematician and friend of Pascal.

Flamsteed, John: Scientist who became England’s first Astronomer Royal.

Galen: Greek physician who flourished in Rome during the second century. His often-erroneous medicine was regarded as sacrosanct by the Church.

Galileo Galilei: Born in Florence during the sixteenth century, regarded as the father of modern science.

Gentileschi, Artemisia: Supremely talented baroque painter, who was raped by the artist Agostino Tassi.

Graunt, John: The father of modern statistics.

Guzmán, Gaspar de (Count-Duke of Olivares): Notoriously incompetent chief minister to Philip IV of Spain.

Halley, Edmund: Scientist in London during the time of Newton. Halley’s Comet is named after him.

Harvey, William: Highly skilled English physician who was the first to correctly demonstrate the circulation of the blood.

Henry VIII: Ruler of England during the sixteenth century; father of Elizabeth I.

Hobbes, Thomas: English writer whose Leviathan revolutionized political thinking.

Hooke, Robert: Multi-talented English scientist.

Huygens, Christiaan: Supreme Dutch scientist who invented the first modern clock.

Janszoon, Willem: Dutch sailor for VOC who became the first European to set foot in Australia.

Jolliet, Louis: French explorer, who along with Jacques Marquette was the first to travel through the North American interior.

Kepler, Johannes: German astronomer who used Brahe’s observations to plot the elliptical orbits of the planets.

La Varenne, François Pierre: French chef who is widely regarded as the founding father of modern French cuisine.

Leibniz, Gottfried: German scientist and rational philosopher who invented calculus independently of Newton.

Leopold I: Holy Roman Emperor.

Locke, John: English philosopher who launched empiricism.

Louis XIV: The Sun King, who ruled France from Versailles.

Lully, Jean-Baptiste: Italian-born French composer.

Mandeville, Bernard: Dutch-born physician whose pioneering work on political economy, The Fable of the Bees, caused a scandal.

Marquette, Father Jacques: French Jesuit explorer, who along with Jolliet was the first to travel through the North American interior.

Medici, Marie de’: Descendant of the famous Florentine banking family who became queen of France.

Melani, Atto: Italian-born castrato singer who flourished in France.

Mersenne, Father Marin: French mathematician who circulated works by great scientists and philosophers from his monastic cell in Paris.

Milton, John: Finest English poet of his time, best known for his Paradise Lost.

Molière: Stage name of the great French dramatist best known for his satire Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme.

Montaigne, Michel de: French philosopher best known for his far-reaching Essays.

Monteverdi, Claudio: Italian musician and composer, who excelled in sacred and secular music, especially opera.

Mustafa Pasha, Kara: Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire who led the Siege of Vienna.

Newton, Isaac: Supreme mathematician and scientist of his age, best known for his work on gravity.

Oldenburg, Henry: German-born scientist who became secretary to the Royal Society in London. Corresponded with scientists throughout Europe.

Pascal, Blaise: Outstanding French mathematician and scientist, who abandoned science for religion.

Pepys, Samuel: English author of the most comprehensive diary of the period, which covers his time as a rising naval administrator.

Peter the Great: Tsar of Russia who attempted to modernize his country; founder of St Petersburg.

Petty, William: Maverick English surveyor of Ireland who produced pioneering ideas of political economy.

Philip IV: Ruler of Spain during its Golden Era.

Poussin, Nicolas: French painter.

Purcell, Henry: English composer.

Racine, Jean: Preeminent French dramatist, famed for his use of language.

Rembrandt van Rijn: Dutch artist now famed for his supreme self-portraits.

Rubens, Peter Paul: Flamboyant Flemish artist and diplomat, the best-known painter of his time.

Spinoza, Baruch: Dutch rationalist philosopher of Portuguese Jewish descent.

Tasman, Abel: Dutch explorer after whom Tasmania is named.

Torricelli, Evangelista: Italian student of Galileo whose inventions include the barometer.

van Dyck, Anthony: Dutch-born artist who flourished as a portrait painter in London during the reign of Charles I.

van Leeuwenhoek, Antonie: Pioneer Dutch observer of the microscopic world.

Velázquez, Diego: Supreme artist at the court of King Philip IV of Spain.

Vermeer, Johannes: Dutch artist who lived in Delft. His supreme gift was never properly recognized during his lifetime.

Witt, Johan de: Dutch politician and friend of Spinoza, who was lynched after he took power.

Wren, Christopher: English polymath who is now best remembered as the architect of St Paul’s Cathedral.

DARK BRILLIANCE

PROLOGUE

DURING THE 1600S, BETWEEN the end of the Renaissance and the start of the Enlightenment, Europe lived through an era known as the Age of Reason. This was a period that saw widespread advances in the arts and sciences. Artists such as Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Van Dyck flourished across the continent. Likewise, scientists such as Newton, Huygens and Pascal continued the Scientific Revolution instigated during the Renaissance by Galileo. Philosophy advanced through rationalists such as Descartes and Spinoza, as well as empiricists such as John Locke, whose ideas would later play a formative role in the American Constitution. At the same time, society began to investigate its own workings. Political theory took on a more profound aspect with Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes. Ideas on economics emerged from such disparate figures as the maverick Englishman Sir William Petty and the French mercantilists who advised Louis XIV, the Sun King, on how to run France.

Yet this was an age of unreason almost as much as it was an age of reason. The above accomplishments took place against a background of extreme political turbulence and irrational behaviour on a continental scale. These took the form of internal conflicts and international wars, as well as more localized manifestations – such as outbreaks of ‘witchcraft’ and the sadistic measures taken against the women deemed responsible. In just the length of a biblical lifetime – ‘threescore years and ten’ – the puritan Pilgrim Fathers who had emigrated to the New World in order to practise their religion in freedom underwent an outbreak of mass hysteria. The result was the notorious Salem witch trials. And by now, the ‘land of liberty’ was also beginning to participate in another form of unreason: the transatlantic slave trade.

These are far from being the only major anomalies of the era, which might justifiably be called the Age of Reason and Unreason. Indeed, the Age of Reason itself was born in Europe at the same time as the greatest outbreak of mass violence yet witnessed on that continent. This was the Thirty Years’ War, a brutal conflict which would devastate central Europe to an extent that would not be seen until the outbreak of the two world wars some three centuries later. Yet, out of this very same war came the Peace of Westphalia, a treaty which formulated the idea of the independent nation-state, a concept that remains a cornerstone of international politics to this day. The Thirty Years’ War was followed by the English Civil War, which was the beginning of the end for the divine right of kings, at least in Britain. It was such turbulence that prompted Hobbes to write his Leviathan. Indeed, many of the greatest works and advances of the Age of Reason were to be inspired (or provoked) by the unreason that gripped Europe.

In some cases, leading figures themselves incorporated both aspects of this divided era. Perhaps none more so than the Italian artist Caravaggio, whose often-violent scenes dramatically capture effects of light and darkness, both literal and metaphorical – a conflict that frequently flared in his own brawling life, during which he committed murder and may even have been murdered himself.

This age also saw the development of European empires across the globe. The English and the Dutch East India Companies were pioneers of intercontinental trade with Asia, ousting the earlier Portuguese trader-explorers. In the process, these companies would develop financial instruments – shares and stock markets – which many regard as the beginnings of modern capitalism. But the subtlety and ingenuity of these rational structures contrast strongly with the grotesque barbarism exhibited by these same companies towards the indigenous populations of India and Indonesia. At the same time, a lucrative new transatlantic commerce opened with the New World. The silver mines of South America, the sugar plantations of the Caribbean, and the cotton trade with the southern colonies of North America all brought transformative riches to western European society. Yet there was a dark underside to this brilliant new wealth: it was dependent upon mass slavery.

This book is intended to illustrate such paradoxes, which were present right from the beginnings of our progressive era. Previous narratives of the Age of Reason have usually concentrated on the rational aspect and the advances of this period. But what precisely is meant by the term ‘reason’? It was viewed then, much as it still is today, as a method of thought which progresses by logical steps towards a proven conclusion. Reason’s use of logic to establish a hitherto-unknown certainty is perhaps best illustrated by its offshoot, mathematics. Here, the entire system is based upon a series of self-evident axioms, upon which all are agreed. Like Euclidean geometry this builds up, step by step, to create an edifice of such certainty and abstract beauty that it is viewed as one of humanity’s finest achievements. The rapture inspired by such a system is well expressed by the twentieth-century mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell:

At the age of eleven, I began Euclid, with my brother as tutor. This was one of the great events of my life, as dazzling as first love. I had not imagined there was anything so delicious in the world. From that moment until I was thirty-eight, mathematics was my chief interest and my chief source of happiness.

Not until the turn of the twentieth century was this sublime aspect of reason replaced, at least to a certain extent. Only then did another offshoot of philosophy, namely psychology, begin to discover that human reason is in reality based upon a far murkier world of instinctive impulses and dark irrational drives. Freud’s unconscious mind is but one manifestation of this not wholly scientific discovery of a world beyond reason.

It now becomes clear that this darker aspect too was part of the Age of Reason, from which our western progressive, liberal, democratic world derives. And now this ‘free’ world is faced with the prospect of placing limits upon itself, in order for the world itself to survive our activities – which have led to climate change, pollution, and the general degradation of our planet. Given such circumstances, it is worth examining precisely how such ‘rational’ progress began. Can we learn from our rational origins – in both their sublime and their darker aspects? Can we discover from this founding myth how our rational world will be able to limit itself in order to preserve the very world we inhabit? Can the world that untrammelled progress has done so much to create, and at the same time destroy, survive itself?

In order to survive, rational progress will inevitably be forced to ration itself. A telling pun. As some commentators have observed, not wholly with irony: if ever there were a time for communism to be invented, it is now! Does this mean that we must inevitably accept a command economy – socialism, no less? It is worth remembering that socialism – especially in its egalitarian aspect – was during the past centuries the great hope of so many enlightened thinkers. Eventually the dream soured and the command economy degenerated into the command of dictatorship. But this would be a later development – a deviation from the original progressive idea that came into being during the Age of Reason, the era which would give birth to western civilization. If this is to endure, what lessons are to be learned from the Age of Reason and Unreason upon which our modern world is founded?

CHAPTER 2

TWO ITALIAN ARTISTS

ITALY REMAINED COMPARATIVELY UNSCATHED during the religious wars which devastated so much of Europe during the early decades of the 1600s. According to the contemporary British historian Diarmaid MacCulloch, ‘Italy was less inclined to the ideals of the Reformation to begin with, and lacked the anti-clerical sentiment that was present in other parts of Europe’. He ascribes this to the widespread participation of the laity in Italian religious life, especially in such organizations as religious guilds, confraternities and oratories.

On the other hand, individuals who publicly proclaimed heretical ideas were liable to fall foul of the Roman Inquisition. Amongst these was the Neapolitan-born Franciscan friar Giordano Bruno, a scientist whose ideas were both far ahead of his time and way behind. In particular, he extended the Copernican view of the solar system to the entire universe, insisting that the stars were also like the sun and had their own orbiting planets. Yet interwoven with such advanced scientific ideas was a curious hermeticism involving Thoth, the Ancient Egyptian god of wisdom, and the moon. Such heresies led to him being burned at the stake in Rome in 1600. Thirty-three years later, it was Galileo’s terror of suffering the same fate which led to him renouncing the Copernican views that he knew to be correct.

Meanwhile, although armies were raised in Italy during this period, their soldiers had little taste for actual combat. The experience of Odoardo Farnese, Duke of Parma, appears to have been typical: ‘Desertion, it seems, was a reality of life more than battle was. Large engagements of entire armies were rare in Italy; a skirmish that killed a few dozen men was on the bloody side. By contrast, Odoardo lost half his army to desertion before he reached his allies’ camp, some 1,500 men in total. Deserters would often be recruited by the other side, and some crossed the lines repeatedly in search of signing bonuses.’

Italy itself may have enjoyed comparative calm during these years, but the same cannot be said for the lives of two leading Italian artists of this period. Namely, the baroque painter and fugitive murderer Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, and the pioneering woman painter Artemisia Gentileschi, who suffered rape, the theft of her works, and even judicial torture by thumbscrew in order to determine the truth of her evidence.