Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

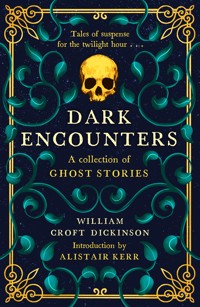

Tales of suspense for the twilight hour... Dark Encounters is a collection of classic and elegantly unsettling ghost stories. A spine-tingling collection, these tales are set in the brooding landscape of Scotland, with an air of historic authenticity – often referring to real events, objects and people. From a demonic text that leaves its readers strangled to the murderous spectre of a feudal baron, this is a crucial addition to the long and distinguished cannon of Scottish ghost stories. For those who seek out the unnerving, the unknown and the unexplainable, Dark Encounters is guaranteed to raise the hair on the back of your neck. This edition features a rare story – 'The MacGregor Skull' – which was the last story every written by the author and posthumously serialised in the Scotsman in 1963.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 286

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dark Encounters

Dark Encounters

A Collection of Ghost Stories

Introduction byAlistair Kerr

First published in Great Britain in 1963 by Harvill Press.This edition published in 2017 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

Introduction copyright © Alistair Kerr

‘The MacGregor Skull’ was first published by The Scotsman in December 1963 and is reproduced here with their kind permission,© The Scotsman Publications Ltd.

Illustrations by James Hutcheson

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders of material reproduced in this book. We would be pleased to rectify any omissions in subsequent editions should they be drawn to our attention.

ISBN 978 1 84697 408 3eBook ISBN 978 0 85790 950 3

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Typeset by 3btype.com, Edinburgh

Contents

Introduction by Alistair Kerr

1 The Keepers of the Wall

2 Return at Dusk

3 The Eve of St Botulph

4 Can These Stones Speak?

5 The Work of Evil

6 The Return of the Native

7 Quieta non Movere

8 Let the Dead Bury the Dead

9 The Castle Guide

10 The Witch’s Bone

11 The Sweet Singers

12 The House of Balfother

13 His Own Number

14 The MacGregor Skull

Notes

A Note on the Author of the Introduction

Introduction

William Croft Dickinson

Scotland is famous for its ghostly tales and traditions, so who better than a former Professor of Scottish History at the University of Edinburgh to present them to a modern readership? William Croft Dickinson has many claims to distinction, but he was also a master of writing spine-chilling – occasionally macabre – stories of the supernatural. He introduces us to his friends and colleagues: historians, scientists, archaeologists and antiquaries, and we share their occult adventures. These are often frightening; sometimes life-threatening, as in Return at Dusk, and occasionally fatal, as in The Eve of St Botulph.

For serious students and aficionados of Scottish history, William Croft Dickinson (1897–1963) needs no introduction. He was arguably the most distinguished twentieth-century historian of Scotland. As John Imrie recalled in his 1966 memoir, Dickinson was the author, co-author or editor of many books on Scottish history, including the New History of Scotland. He edited for publication a large number of primary sources; especially old court books and burgh records, one of which was The Fife Sheriff Court Book. These records give a fascinating contemporary picture of Scottish society and culture. He was (to date) the longest-serving Fraser Professor of Scottish History and Palaeography at the University of Edinburgh, occupying that Chair from 1944 until his death in 1963. A few months before he died he received the distinction of Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE) for his services to the discipline of history.

Outside the university Dickinson served on the Scottish Records Office Advisory Council, as a Trustee of the National Library of Scotland, as a member of the former Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS) and on the Councils of the Scottish History Society and the Stair Society, which is concerned with promoting knowledge of the history of Scots law. In the words of his successor, Professor Gordon Donaldson, ‘His services to Scottish history were many, but none of them surpassed in importance his work on this Review’. The periodical in question was The Scottish Historical Review, in which Dickinson’s first published work had appeared in 1922 and which he had revived and refounded in 1947.

Dickinson, however, was more than just a brilliant academic historian. He was also a first-rate university administrator; these two accomplishments do not necessarily go together. He was an accomplished lecturer and raconteur. He was also a man of action: Dickinson’s MA degree course began in 1915 but he did not graduate, with a first in history, until 1921: the First World War interrupted his studies at St Andrews. In 1916 he volunteered for service with the Royal Highland Regiment (RHR), usually known as the Black Watch. He was later commissioned in the Machine Gun Corps. His courage and leadership won him the Military Cross for ‘conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty’ in an action near Ypres in 1917. Dickinson remained something of the old soldier thereafter. He attributed his formidable organisational and administrative skills to his army training. While most of his students found him a sympathetic and even inspirational teacher, he was especially friendly to former servicemen, many of whom he taught after the Second World War.

In the inter-war period Dickinson held teaching posts at the London School of Economics (LSE) while continuing to visit Scotland to attend relevant conferences and to write articles and books on Scottish history. He spent most of the Second World War until 1944 as the LSE’s Librarian. In that year he took up his Professorial Chair in Edinburgh.

Despite his many admirable qualities, Dickinson had his critics; for a start, he was by no means politically correct. His English Nonconformist upbringing had influenced him to take a perceptibly Protestant partisan approach to some historical topics, including the Scottish Reformation. This was one of his favourite subjects, on which he lectured pungently and with verve. Reportedly there was once a walk-out by Roman Catholic students in protest at some of his remarks. Dickinson’s first ghost story, published in Blackwood’s Magazine, seems to show empathy with the seventeenth-century Presbyterian Covenanters, which Scottish Episcopalians and Catholics might not necessarily share. It is nonetheless an excellent ghost story.

Second, Dickinson chose to write fiction, including ghost stories, as well as history. Some of his colleagues disapproved of his fiction writing; it is not entirely clear why. The reason may be that many historians prefer to read factual accounts of what really happened rather than imaginary ones describing what might, could or ought to have occurred, and it must be admitted that the historic reality is sometimes more interesting and bizarre than any novelist’s imagination; you literally could not invent it. Moreover they do not like to appear to endorse popular superstitions and other unverified traditions, even by indirect association.

Third, Dickinson was undeniably English, without any known Scots ancestry. This could have counted against him, at least in the early days. He had been born in Leicester and educated at Mill Hill prior to his studies at St Andrews. He nevertheless knew far more about Scottish history than most birthright Scots: he taught the subject, researched it and wrote extensively about it. Despite this, even now lecturers and historians are apt occasionally to say and write that ‘Dickinson was a great authority on Scottish History, although he was in fact English’, as though that were slightly incongruous. Yet English people lecturing in Scottish universities – and vice-versa – are hardly unusual: would they have made that point if he had been lecturing and writing about, for example, African or Ancient History? In reality Dickinson had become thoroughly Scots at an early stage. His first year at St Andrews was probably the start of his love affair with Scotland and its past. His wartime service, initially with the Black Watch, helped the process of assimilation.

Dickinson seems to have belonged to a particular type of Englishman – perhaps more common in the past than now – who, often from an early age, identifies strongly and inexplicably with another people or culture. In some cases the identification is so strong as almost to suggest the possibility of reincarnation; of having genuinely belonged to that nation in a past life. This type, in cases where the country of their elective affinity was Scotland, could sometimes be encountered serving in the old Highland Infantry Regiments, like the Black Watch, which they had joined, inter alia, in order to wear the kilt. Other examples of this phenomenon include the late Dr Patrick Barden, who was born in Eastbourne but who became a distinguished Scot, a well-known herald painter and a breeder of pedigree Highland cattle; Hugh Dormer DSO, who had a visceral attachment to France, where he was killed in 1944; and Captain Robert Nairac GC, whose deep emotional involvement with Ireland was a factor in his murder there in 1977.

Dickinson’s interest in writing fiction received encouragement as a result of his marriage. In 1930 he married Florence Tomlinson, the daughter of H.M. Tomlinson, novelist, journalist, and biographer of Norman Douglas. Their only daughter, Susan Dickinson, would become a woman of letters, a publisher and a collector and editor of ghost stories, including her father’s.

Dickinson wrote three novels for children: Borrobil (1944), The Eildon Tree (1947) and The Flag from the Isles (1951). They received critical acclaim and have been compared to the children’s novels of Dickinson’s contemporaries C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, although they are now less well known than the Narnia books or The Hobbit. In subject matter they were closer to Rosemary Sutcliffe’s historical novels; like them, Dickinson’s books were intended to awaken an interest in history in their young readers. For an older age group he wrote Two Students at St Andrews 1711–1716 (1952), a delightful book, which is thinly disguised biography and draws heavily on family letters, diaries and other contemporary sources.

Historical novels for younger readers are one thing: many young people have been inspired to study the subject, having first read historical fiction by Kipling, G.A. Henty or Rosemary Sutcliffe, so they arguably serve a useful purpose. Ghost stories are another matter; some scholars perceive them as not quite intellectually respectable and as belonging to a literary demimonde. At best they may be a hobby-genre for the diversion of serious writers like Dickens or Henry James. Dickinson did not agree; in his view ghost stories, legends and superstitions were of legitimate interest to historians, forming part of the historical narrative and providing insights into the popular culture of the period. His interest in ghost stories was stimulated by the folk legends that he unearthed in the course of his researches and travels around Scotland. Dickinson’s opinion shows how authentically Scots he had become: Scots, like other Celts, tend to treat the paranormal or supernatural as part of the natural order of things. Belief in such phenomena as the second sight is not confined to poorly educated people living in remote rural areas; it seems still to be widespread. Appropriately, the Koestler Parapsychology Unit, which studies alleged psychic phenomena among other things, has since 1985 been based within the University of Edinburgh.

That being so, it is not surprising that there should be an ancient and respectable tradition of composing ghost stories in Scotland. It goes back to pre-literate days, when a brilliant storyteller, especially if he were also a poet or minstrel, was equally welcome in the peasant’s hut or the nobleman’s castle. That tradition survived well within living memory: for example, it was common for older family members to tell ghost stories, or recite ghostly poems, to their children, grandchildren, nephews and nieces around the fire at Christmas and on other winter nights, to give them a pleasurable fright. Even after most of the population had become literate, this custom continued; as recently as the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many published ghost stories were clearly intended to be read aloud, especially at Christmas.

Because of this rich tradition, many of Scotland’s finest authors have tried their hand at writing ghost stories. Two of the most spine- chilling ones ever written, The Tapestried Chamber and Wandering Willie’s Tale, came from the pen of no less a wordsmith than Sir Walter Scott. Others who have done so include Robert Burns, as author of Tam O’Shanter; James Hogg (the Ettrick Shepherd); Mrs Margaret Oliphant, author of The Open Door and other stories; Robert Louis Stevenson; Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (born in Edinburgh and a graduate of the University of Edinburgh, albeit of Irish descent); John Buchan, George Mackay Brown and, unexpectedly, Muriel Spark. Ian Rankin, the author of the Rebus detective novels, has his moments of supernatural spookiness, too. To these might be added Algernon Blackwood, who was born in London and later moved to Canada but studied at Edinburgh (he left the university without a degree) and who set at least one of his eerie tales in Edinburgh. By choosing to write ghost stories, Dickinson placed himself firmly within a well-established Scottish literary tradition. All of his ghost stories take place within his adopted country of Scotland.

The next question is: what stimulated Dickinson to start writing ghost stories? The timing may offer a clue. His first one, entitled ‘A Professor’s Ghost Story’, appeared in Blackwood’s Magazine in 1947, three years after Dickinson had moved to Edinburgh, and it attracted favourable comment. Six years later, in 1953, it was reissued under a new name as the title story in a collection of four ghost stories: The Sweet Singers and Three Other Remarkable Occurrents, published by Oliver & Boyd and illustrated with atmospheric engravings by Joan Hassall. Copies of this book, its cover decorated with an austerely attractive postwar design, are uncommon and collectable. The flattering publisher’s note explains that:

We have come to expect much from our scholars and scientists, but it is seldom that we can greet them on common ground. Here we have a group of ghost stories having a background such as only the scholar can provide. Neat and compact, told with great charm and an undoubted flair, these stories make us realize that old shades can have new mystery when related to our present day and age.

Each has its own ‘atmosphere’ – a word that has a fatal attraction for the antiquary in ‘The Eve of St Botulph’. Each is based upon some known fact or episode in Scotland’s past; but in each the past disturbs the present by a ‘Return at Dusk’ in some questionable shape.

The opening story, ‘The Sweet Singers’, which has as its background the imprisonment of the Covenanters on the Bass Rock, was widely acclaimed when printed some six years ago in Blackwood’s Magazine.

The second story, which is not mentioned in the publisher’s note, is ‘Can These Stones Speak?’. It is set in an unnamed Scottish university town, which might be Aberdeen or St Andrews, and involves a horrible episode of time travel by an academic, who unwillingly witnesses the immurement – the walling-in – of a live, and presumably sexually incontinent, nun during the Middle Ages. The fourth and last story, ‘Return at Dusk’, is in many readers’ view the most frightening. The Second World War is in progress and the army has requisitioned an old Scottish castle for a secret project. A young officer is posted to the castle, innocently unaware that he is descended from the noble family who formerly lived there and that waiting for him is the vengeful ghost of an hereditary enemy. The scene is now set for supernatural mayhem and Dickinson does not disappoint.

From their dates of publication, it seems that his return to Scotland, or at any rate the research that he undertook after his arrival, stimulated Dickinson to start writing his ghost stories. He would discover many sinister tales in the course of his travels all over Scotland on behalf of the RCAHMS, but in truth he did not need to look far beyond his own workplace and home area. Edinburgh, according to ghost hunters, is the most haunted city in the UK apart from London, which is considerably larger.

There are many Edinburgh ghost tales; they keep the operators of ‘ghost tour’ companies gainfully employed during the summer months. The castle is haunted; the palace is haunted. So are many other places. According to legend, the unlucky belated pedestrian risks encountering a tall, black-cloaked man in the costume of a bygone age, whose carved walking-stick hops ahead of him down the pavement, any time after midnight in the West Bow. That ancient thoroughfare is near both the university and George IV Bridge, where Dickinson bought his pipe tobacco from Macdonald the tobacconist. The ghost is the shade of Major Thomas Weir (1599–1670), an evil seventeenth-century commander of the Town Guard, who escorted Montrose to the scaffold and was later executed in his turn as a self-confessed warlock and murderer, having previously been regarded as an exceptionally devout Presbyterian. (He may also have been an original of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde; Robert Louis Stevenson was familiar with his story.) A Victorian anatomist in a black frock-coat frequents the former Medical School at night. Greyfriars, the University Church, has one of the most interesting and numinous graveyards in the UK. Many famous and notorious people lie there; I hesitate to write “repose”. They include Sir George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh (1636/38–1691), nicknamed ‘The Bluidy Mackenzie’, who supposedly does not rest quietly in his grand mausoleum. Mackenzie was in reality a distinguished lawyer, a highly cultured and much maligned man who backed the wrong political horse in 1688, but in popular myth he has become the demonic Scots equivalent of Judge Jefferies of the Bloody Assize, who is also the subject of ghost stories.

Sometimes the ghosts can become a positive nuisance; for example, according to Sir Walter Scott, the exasperated owners of Major Weir’s former residence had it pulled down in 1830 because it had become a liability. The building was so disagreeably haunted that latterly nobody would live in it, not even if they were paid to do so.

The Dickinsons settled in Fairmilehead, which is now a leafy suburb but was then on the extreme southernmost edge of Edinburgh and still almost rural, with working farms nearby. There they generously entertained his students, although getting to Fairmilehead involved the undergraduates in a long journey by tram – latterly by bus – or bike from central Edinburgh. Outside the city boundary, but still within easy reach of Fairmilehead, were two of Scotland’s most famous haunted locations: Woodhouselee, an old aristocratic country house, now owned by the university’s Department of Agriculture, and Roslin Chapel and Castle.

Woodhouselee is said to be haunted, among others, by the ghost of Lady Anne Sinclair, a former owner’s wife, who was evicted with her infant child in midwinter on the order of the then Regent of Scotland, James Stewart, Earl of Moray. They perished. It is said that their ghosts haunt the site and their screams can still be heard. Interestingly, the tragedy actually took place at Old Woodhouselee, several miles away and now an insignificant ruin. Many of its stones, however, were recycled to build the present Woodhouselee. The ghosts reportedly clung to the stones and continued to haunt the later house. In revenge, Lady Anne’s widower, James Hamilton of Bothwellhaugh, stalked the Regent, finally ambushing him in Linlithgow in 1570. He fired a single shot at the Regent, leaving him with fatal wounds, and fled on horseback. This was the first recorded assassination by firearm.

Roslin is the scene of several authentic traditional ghost stories, one of which is related in Scott’s poem Rosabelle, while another involves a gigantic spectral wolfhound, the Mauthe Dog, as well as more recent spurious legends invented by Dan Brown for The Da Vinci Code; a novel whose flagrant historical inaccuracies would have driven Dickinson up the wall.

It is likely that more than one writer influenced Dickinson’s ghost stories, but the most obvious influence is that of Montague Rhodes James (M.R. James, 1862–1936), the author of Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, which is considered to include some of the most accomplished and terrifying ghost stories in English, including certain ones, like ‘Count Magnus’ and ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’, which have become internationally famous. Ghost Stories of an Antiquary has never gone out of print. Many of the stories have been adapted for film, television, radio or stage performance. Among other appointments, James served as Provost of King’s College, Cambridge (1905–18) and of Eton College (1918–36). Dickinson seems to have enjoyed James’s stories. Given that he was teaching in London during the interwar years, he could have met James, who survived until 1936, but I have seen no evidence that he ever did so; James latterly lived a fairly reclusive existence at Eton. Dickinson had, however, visited Cambridge; it is possible that he became acquainted there with some of James’s friends and former colleagues. A few clues in his stories might imply this.

There are undoubted similarities between James’s and Dickinson’s style and content. This has led some critics to regard Dickinson as little more than a member of James’s ‘school’, writing in careful and derivative imitation of his master. That does not do justice to Dickinson’s originality, although both authors used an elegant, understated and scholarly style, as though they were narrating genuine historical events for well-educated and informed readers. Both could faultlessly reproduce the prose of past eras. The most terrifying conclusions are seldom spelled out; the reader is often left to work out what must have happened and the penny can take a few moments to drop. Both authors tend to use realistic contemporary settings, at least at the start of their stories. They may subsequently travel back in time. In several Dickinson stories the narrative begins with a group of academics reminiscing in front of the fire in the Edinburgh University Staff Club, which was then located in the Old College. Something suddenly prompts one of them to recount a curious tale . . . In M.R. James’s stories the academics’ conversation takes a similar turn, but the location is the High Table or Combination Room of an ancient Cambridge College.

Both authors have a tendency to involve real people, objects, places and historic events in their ghost fiction, which adds to its air of authenticity. In Dickinson’s case one story, ‘The Witch’s Bone’, centres on a magical relic or talisman which is kept in a museum. The National Museum of Scotland possesses such a bone and, although it is not on display, Dickinson evidently knew of it and wrote a story about it. In ‘The Sweet Singers’ mention is made of a real rare book, Jehovah Jireh (1643), a copy of which is held by the University Library. Another rare book, allegedly held in the same library, appears in ‘The Work of Evil’. I have not sought it out; it is apparently a magical treatise that brings early death to people foolish enough to consult it.

Although Dickinson gave the real locations of some of his stories – ‘The Eve of St Botulph’ takes place among the ruins of Dundrennan Abbey, for example – in other stories he does not. Readers can have fun trying to work out the location in these cases. ‘Quieta non Movere’, aka ‘The Black Dog of Wolf ’s Craig’, is in fact set at Fast Castle in East Lothian, but Sir Walter Scott had renamed Fast Castle ‘Wolf ’s Craig’ in his novel The Bride of Lammermuir, so Dickinson decided to use that name. Joan Hassall’s illustrations and hints dropped by Dickinson himself suggest that he had the picturesque Craigievar Castle in mind for the castle in ‘Return at Dusk’, although this building – formerly a Forbes family residence and now a National Trust for Scotland property – was never requisitioned by the army. It is, however, home to several ghosts and is the scene of one particular ghost legend that resembles the terrifying legend in ‘Return at Dusk’. Although Craigievar was inhabited and therefore not open to the public until after 1963, the year of Dickinson’s death, he evidently visited it and learned about their legend from the Forbes family or from local people.

There are important differences between James’s and Dickinson’s work. They belonged to different generations, having been born thirty-five years apart. A vast gulf of experience separated them because Dickinson served in the Great War and James, who was fifty-two in 1914, did not. James’s historical consciousness stopped at the latest in about 1910. Although he lived until 1936 and even after 1918 he continued to improve and edit his stories for republication; occasionally writing, or starting to write, new ones, James took no account of the changes that had happened in England since August 1914. Some of his stories take place as long ago as the seventeenth or eighteenth, but for the most part they happen in the later nineteenth or early twentieth, centuries. England is seated amid honour and plenty; still the richest country on Earth. The country houses are intact; their old families still usually live in them, although nouveaux riches occasionally rent or acquire them. Following some alarming psychic disturbance, they sometimes end by wishing that they had not. Dons and clergymen occupy an honoured position in society. The strong pound Sterling gives gentlemen antiquaries a favourable exchange rate, allowing them to travel at leisure and in comfort around an unspoiled Europe, where their researches, begun in all innocence, are apt to place them in danger. Trains are frequent and reliable; characters living in the depths of the country can easily ‘run up to London’ for a day in order to consult a book in a library, visit the British Museum or talk to an expert. France, Germany and the Low Countries are easily accessible; Scandinavia and other regions seem remote.

By contrast, only a few of Dickinson’s stories take place earlier than the Second World War, although they often have echoes from an earlier period, which can suddenly come back to life and may prove lethal. The main action normally happens in the 1940s, 1950s or the very early 1960s. Dickinson’s characters tend to have served in one or both World Wars. Academics now live frugally and pass their holidays playing golf , hill-walking or on archaeological digs in Scotland.

Dickinson lived into the early computer age and was aware of its possibilities; the University of Edinburgh was in the forefront of the development of artificial intelligence and no doubt the latest developments were excitedly discussed in the University Staff Club. He wrote at an interesting moment in the development of the supernatural story: when it started to embrace modern science, including computers and psychology. The distinction between ghost stories and science fiction was becoming slightly blurred. Thus he bridges the gap between M.R. James and modern writers like Ray Russell and Stephen King.

In one of the last of Dickinson’s ghost stories, ‘His Own Number’ (1963), related by a professor of geography, an evil spirit becomes computer-literate and predicts the precise location and grid reference of a technician’s death, which it causes. There is a comparable and apparently authentic computer ghost story – or urban legend – about one of the older Cambridge Colleges. Using a computer, the ghost issues warnings and threats which are more explicit than those in ‘His Own Number’. To date it has reportedly killed two people who disregarded them and the college has banned any further research on the subject: as a result, I have been unable to discover when the alleged hauntings are supposed to have begun. If it should prove that they started after 1963, clearly Dickinson could not have been aware of them or have used them in his story, but it is still an intriguing coincidence. Details may be found in Cambridge College Ghosts by Geoff Yeates (Jarrold, 1994).

Although Dickinson’s admirers consider that, at his best, he was as good as M.R. James, their posthumous literary fortunes have been different. William Croft Dickinson’s reputation as a Scottish historian remains immense, while his ghost stories, despite their merits, are now largely forgotten. By contrast M.R. James has achieved international fame on the basis of Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, while his important work as a mediaevalist and biblical scholar, including an invaluable English edition of the Apocryphal New Testament, is unknown to most people. This may irritate his ghost but on the other hand, until the copyright expired in 2007, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary and the various adaptations for stage and cinema must have been a wonderful source of revenue for his estate.

While M.R. James or his literary agent had marketed Ghost Stories of an Antiquary professionally, collecting them into two volumes, later into one, and bringing out new improved editions, that did not happen to Dickinson’s ghost stories. This may reflect the fact that, as the holder of a Professorial Chair and having many other commitments, he simply did not have much time to devote to promoting his works of fiction. After he published The Sweet Singers and Three Other Remarkable Occurrents in 1953, no further collections appeared until Dark Encounters, which Dickinson edited on his deathbed and which brought together almost all of Dickinson’s ghost stories. It was published posthumously by Harvill Press in 1963.

In the interim Dickinson continued to write ghost stories; they appeared in magazines and in the Christmas issues of The Scotsman. Dickinson had undertaken to write a ghost story for that Edinburgh newspaper every year, starting in 1957. He did so until 1963; his last story, ‘The MacGregor Skull’, was published posthumously that year. The invitation to provide the annual Christmas ghost story was flattering but, as December began to draw near, inspiration sometimes proved elusive; the story, however, had to be written. The quality of Dickinson’s last stories is uneven; a few seem slightly to lack spontaneity. Nevertheless the series was judged to have been a great success. It continued for many years after Dickinson’s death, with other well-known writers, such as George Mackay Brown, writing the ghost stories. An obvious drawback to publication in a periodical was that the stories were read and admired but the magazine or newspaper was later discarded and the story forgotten.

A further possible reason for the stories’ eclipse may be that Dickinson set all of them in Scotland, so they might have become unfairly pigeon-holed in critics’ and publishers’ minds as ‘Scottish interest only’. That ought not to be counted against them, but by contrast M.R. James’s tales take place in England – especially his beloved East Anglia – France, Sweden, Denmark and Germany. This may have given them a wider appeal.

‘The MacGregor Skull’ was missed out of Dark Encounters in 1963, probably through an oversight. It was omitted again in 1984, when Dark Encounters was republished by Wendover Goodchild with an introduction by Susan Dickinson. No further editions have appeared, although individual Dickinson stories have occasionally been included in anthologies of ghost stories, some of which Susan Dickinson edited; for example, in The Armada Book of Ghost Stories.

Now that you know something of the author’s distinguished career, your next question is likely to be: ‘Have his stories stood the test of time?’ I think so: the proof of the pudding is in the eating. A few years ago I was house-sitting for a friend, alone in an old Georgian house in an ancient cathedral town. One gloomy evening, when there was nothing of interest on television, I made the grave error of reading some of Dickinson’s ghost stories, which I had not read for many years, from my host’s extensive library of detection, mystery and horror. I found that they still had the power to raise the hair on the back of my neck; especially ‘Return at Dusk’. I did not get much sleep that night.

A new edition of Dark Encounters has long been overdue: I feel honoured to have been invited to write the introduction to these powerful stories. Enjoy them!

The Keepers of the Wall

The Keepers of the Wall

‘I SEE THAT someone has discovered a number of skeletons beneath the foundations of a wall and has brought forward the old idea that they were put there so that their ghosts could hold up the wall.’

‘And why not?’ interposed Henderson. ‘It was long thought that burying a body under a wall would help to hold the wall secure.’

‘Didn’t Gordon Childe find something like that at Skara Brae?’ queried Drummond.

‘Yes,’ Henderson confirmed. ‘He found the skeletons of two old women at the foot of one of the walls; but he made only a suggestion that possibly they had been buried there so that their ghosts could hold up the wall. A guess, if you like. But a good guess.’

‘I could tell you of a much more modern instance,’ put in Robson, our new Professor of Mediaeval Archaeology. And I noticed that he spoke hesitantly. ‘A sixteenth-century instance. Ghosts to hold up a wall. Perhaps even ghosts to gather the living to help them in their task,’ he added slowly. ‘Don’t ask me to explain what I mean by that. I just don’t know. All I know is that recently I had a terrifying experience on the west coast – an experience that still makes me frightened of visiting ancient ruins by night.’

‘I once had a terrifying experience myself,’ said Drummond, quietly. ‘You’ll find at least one listener who’ll understand. And the oftener you tell a tale, the less it haunts you.’

‘Well, perhaps I’ll find some of your relief, Drummond, by telling you the story of my night in the castle of Dunross – in March of this year, just before I came to Edinburgh to take up my chair.’