Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

"IMAGINE A PERSON, TALL, LEAN, AND FELINE, HIGH-SHOULDERD, WITH A BROW LIKE SHAKESPEARE AND A FACE LIKE SATAN..." LONDON, 1913 — the era of Sherlock Holmes, Dracula, and the Invisible Man. A time of shadows, secret societies, and dens filled with opium addicts. Into this world comes the most fantastic emissary of evil society has ever known... FU-MANCHU "Fu-Manchu is the undisputed king of all evil masterminds." — Jonathan Maberry, NY Times bestselling author of Assassin's Code FAH LO SUEE - DAUGHTER OF FU-MANCHU As far as the world knows, Fu-Manchu is dead, leaving a vacuum within the league of assassins known as the Si-Fan. Into the void steps the daughter of the devil, whose machinations are every bit as deadly as those of her infamous father. AFTERWORD BY LESLIE S. KLINGER (THE ANNOTATED SANDMAN BY NEIL GAIMAN)

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 302

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

“Without Fu-Manchu we wouldn’t have Dr. No, Doctor Doom or Dr. Evil. Sax Rohmer created the first truly great evil mastermind. Devious, inventive, complex, and fascinating. These novels inspired a century of great thrillers!”

Jonathan Maberry, New York Times bestselling author of Assassin’s Code and Patient Zero

“The true king of the pulp mystery is Sax Rohmer—and the shining ruby in his crown is without a doubt his Fu-Manchu stories.”

James Rollins, New York Times bestselling author of The Devil Colony

“Fu-Manchu remains the definitive diabolical mastermind of the 20th Century. Though the arch-villain is ‘the Yellow Peril incarnate,’ Rohmer shows an interest in other cultures and allows his protagonist a complex set of motivations and a code of honor which often make him seem a better man than his Western antagonists. At their best, these books are very superior pulp fiction… at their worst, they’re still gruesomely readable.”

Kim Newman, award-winning author of Anno Dracula

“Sax Rohmer is one of the great thriller writers of all time! Rohmer created in Fu-Manchu the model for the super-villains of James Bond, and his hero Nayland Smith and Dr. Petrie are worthy stand-ins for Holmes and Watson… though Fu-Manchu makes Professor Moriarty seem an under-achiever.”

Max Allan Collins, New York Times bestselling author of The Road to Perdition

“I grew up reading Sax Rohmer’s Fu-Manchu novels, in cheap paperback editions with appropriately lurid covers. They completely entranced me with their vision of a world constantly simmering with intrigue and wildly overheated ambitions. Even without all the exotic detail supplied by Rohmer’s imagination, I knew full well that world wasn’t the same as the one I lived in… For that alone, I’m grateful for all the hours I spent chasing around with Nayland Smith and his stalwart associates, though really my heart was always on their intimidating opponent’s side.”

K. W. Jeter, acclaimed author of Infernal Devices

“A sterling example of the classic adventure story, full of excitement and intrigue. Fu-Manchu is up there with Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, and Zorro—or more precisely with Professor Moriarty, Captain Nemo, Darth Vader, and Lex Luthor—in the imaginations of generations of readers and moviegoers.”

Charles Ardai, award-winning novelist and founder of Hard Case Crime

“I love Fu-Manchu, the way you can only love the really GREAT villains. Though I read these books years ago he is still with me, living somewhere deep down in my guts, between Professor Moriarty and Dracula, plotting some wonderfully hideous revenge against an unsuspecting mankind.”

Mike Mignola, creator of Hellboy

“Fu-Manchu is one of the great villains in pop culture history, insidious and brilliant. Discover him if you dare!”

Christopher Golden, New York Times bestselling co-author of Baltimore: The Plague Ships

THE COMPLETE FU-MANCHU SERIES

BY SAX ROHMER

Available now from Titan Books:

THE MYSTERY OF DR. FU-MANCHU

THE RETURN OF DR. FU-MANCHU

THE HAND OF FU-MANCHU

Coming soon from Titan Books:

THE MASK OF FU-MANCHU

THE BRIDE OF FU-MANCHU

THE TRAIL OF FU-MANCHU

PRESIDENT FU-MANCHU

THE DRUMS OF FU-MANCHU

THE ISLAND OF FU-MANCHU

THE SHADOW OF FU-MANCHU

RE-ENTER FU-MANCHU

EMPEROR FU-MANCHU

THE WRATH OF FU-MANCHU AND OTHER STORIES

DAUGHTER OFFU-MANCHU

SAX ROHMER

TITAN BOOKS

DAUGHTER OF FU-MANCHU

Print edition ISBN: 9780857686060

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857686725

Published by Titan Books A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd 144 Southwark St London SE1 0UP

First edition: September 2012

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First published as a novel in the UK by William Collins & Co. Ltd, 1931 First published as a novel in the US by Doubleday, Doran, 1931

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

The Authors Guild and the Society of Authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 2012 The Authors Guild and the Society of Authors

Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

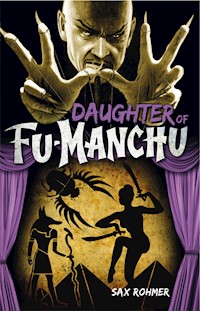

Frontispiece illustration by John Richard Flanagan, detail from an illustration for “Fu Manchu’s Daughter,” first appearing in Collier’s Weekly, May 17 1930. Special thanks to Dr. Lawrence Knapp for the illustrations as they appeared on “The Page of Fu-Manchu” - www.njedge.net/~knapp/FuFrames.htm

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the United States.

Contents

Title Page

Part One

Chapter One: The Living Death

Chapter Two: Rima

Chapter Three: Tomb of the Black Ape

Part Two

Chapter Four: Fah Lo Suee

Chapter Five: Nayland Smith Explains

Chapter Six: The Council of Seven

Part Three

Chapter Seven: Kâli

Chapter Eight: Swâzi Pasha Arrives

Chapter Nine: The Man from El-Khârga

Part Four

Chapter Ten: Abbots Hold

Chapter Eleven: Dr. Amber

Chapter Twelve: Loro of the Si-Fan

“She continued to watch me. I tried to hate her. But her eyes caressed me, and I was afraid—horribly afraid of this witch-woman who had the uncanny power which was Circe’s, of stealing men’s souls.”

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

THE LIVING DEATH

Just in sight of Shepheard’s I pulled up.

I believe a sense of being followed is a recognized nervous disorder. But it was one I had never experienced without finding it to be based on fact.

Certainly what had occurred was calculated to upset the stoutest nerves. To lose an old and deeply respected friend, and in the very hour of the loss to be confronted by a mystery seemingly defying natural laws, is a test of staying power which any man might shirk.

I had set out for Cairo in a frame of mind which I shall not attempt to describe. But this damnable idea that I was spied upon— followed—asserted itself in the first place on the train.

In spirit still back in camp beside the body of my poor chief, I suddenly became conscious of queer wanderers in the corridor. One yellow face in particular I had detected peering in at me, which possessed such unusual and dreadful malignity that at some point just below Beni Suef I toured the cars from end to end determined to convince myself that those oblique squinting eyes were not a product of my imagination. Several times I had fallen into a semi-doze, for I had had no proper sleep for forty-eight hours.

I failed to find the yellow horror. This had disturbed me, because it made me distrust myself. But it served to banish my sleepiness. Reinforced with a stiff whisky-and-soda, I stayed very widely awake as the train passed station after station in the Nile Valley and drew ever nearer to Cairo.

The squinting eyes did not reappear.

Then, having hailed a taxi outside the station, I suddenly became aware, in some quite definite way, that the watcher was following again. In sight of Shepheard’s I pulled up, dismissed the taxi, and mounted the steps to the terrace.

Tables were prepared for tea, but few as yet were occupied. I could see no one I knew, but of this I was rather glad.

Standing beside one of those large ornamental vases at the head of the steps, I craned over, looking left along Sharia Kamel. I was just in time. My trick had its reward.

A limousine driven by an Arab chauffeur passed in a flash.

But the oblique squinting eyes of its occupant stared up at the balcony. It was the man of the train. I had not been dreaming.

I think he saw me, but of this I couldn’t be sure. The car did not slacken speed and I lost sight of it at the bend by Esbekiyeh Gardens.

A white-robed, red-capped waiter approached. Mentally reviewing my condition and my needs, I ordered a pot of Arab coffee. I smoked a pipe, drank my coffee, and set out on foot for the club. Here I obtained the address I wanted…

In a quiet thoroughfare a brass plate beside a courtyard entrance confirmed its correctness. In response to my ring a Nubian servant admitted me. I was led upstairs and without any ceremony shown into a large and delightfully furnished study.

The windows opened on a balcony draped with purple blossom and overhanging the courtyard where orange trees grew. There were many books and the place was full of flowers. In its arrangement, the rugs upon the floor, the ornaments, the very setting of the big writing table, I detected the hand of a woman. And I realized more keenly than ever what a bachelor misses and the price he pays for his rather overrated freedom.

My thoughts strayed for a moment to Rima, and I wondered, as I had wondered many many times, what I could have done to offend her. I was brought back sharply when I met the glance of a pair of steady eyes regarding me from beyond the big writing table.

The man I had come to see stood up with a welcoming smile. He was definitely a handsome man, gray at the temples and well set up. His atmosphere created an odd sense of security. In fact my first impression went far to explain much that I had heard of him.

“Dr. Petrie?” I asked.

He extended his hand across the table and I grasped it.

“I’m glad you have come, Mr. Greville,” he replied. They sent me your message from the club.“ His smile vanished and his face became very stern. “Please try the armchair. Cigars in the wooden box, cigarettes in the other. Or here’s a very decent pipe mixture”— sliding his pouch across the table.

“Thanks,” I said; “a pipe, I think.”

“You are shaken up,” he went on—“naturally. May I prescribe?”

I smiled, perhaps a little ruefully.

“Not at the moment. I have been rather overdoing it on the train, trying to keep myself awake.”

I filled a pipe whilst trying to muster my ideas. Then, glancing up, I met the doctor’s steady gaze; and:

“Your news was a great shock to me,” he said. “Barton, I know, was one of your oldest friends. He was also one of mine. Tell me— I’m all anxiety to hear.”

At that I began,

“As you may have heard, Dr. Petrie, we are excavating what is known as Lafleur’s Tomb at the head of the Valley of the Kings. It’s a queer business and the dear old chief was always frightfully reticent about his aims. He was generous enough when a job was done and shared the credit more than fairly. But his sense of the dramatic made him a bit difficult. Therefore, I can’t tell you very much about it. But two days ago he shifted the quarters, barred all approaches to the excavation, and generally behaved in a way which I knew from experience to mean that we were on the verge of some big discovery.

“We have two huts, but nobody sleeps in them. We are a small party and under canvas. But all this you will see for yourself—at least, I hope I can count on you? We shall have to rush for it.”

“I am coming,” Dr. Petrie replied quietly. “It’s all arranged. God knows what use I can be. But since he wished it…”

“Some time last night,” I presently went on, “I heard, or thought I heard, the chief call me: ‘Greville! Greville!’ His voice seemed strange in some way. I fell out of bed (it was pitch dark), jumped into slippers, and groped along to his tent.”

I stopped. The reality and the horror of it stopped me. But at last:

“He was dead,” I said. “Dead in his bed. A pencil had dropped from his fingers and the scribbling block which he used for notes lay on the floor beside him.”

“One moment,” Dr. Petrie interrupted me. “You say he was dead. Was this impression confirmed afterwards?”

“Forester, our chemist,” I replied sadly, “is an M.R.-C.P. though he doesn’t practise. The chief was dead. Sir Lionel Barton—the greatest Orientalist our old country has ever produced, Dr. Petrie. And he was so alive, so vital, so keen and enthusiastic.”

“Good God!” Dr. Petrie murmured. “To what did Forester ascribe death?”

“Heart failure—a quite unsuspected weakness.”

“Unaccountable! I could have sworn the man had a heart like an ox. But I am becoming somewhat puzzled, Mr. Greville. If Forester certified death from syncope, who sent me this?”

He passed a telegram across the table. I read it in growing bewilderment:

Sir Lionel Barton suffering catalepsy. Please come first train and bring antidote if any remains.

I stared at Petrie, then:

“No one in our camp sent it!” I said.

“What!”

“I assure you. No member of our party sent this message.”

I saw that it had been delivered that morning and had been handed in at Luxor at Six A.M. I began to read it aloud in a dazed way. And, whilst I was reading, a subdued but particularly eerie cry came from the courtyard. I stopped. It startled me. But its effect upon Dr. Petrie was amazing. He sprang up as though a shot had been fired in the room and leaped towards the open window.

“What was it?” I exclaimed.

Whilst the cry had not resembled any of the many with which I was acquainted in the land where the vendor of dates, of lemonade, of water, of a score of commodities has each his separate song, yet, though weird, it was not in itself definitely horrible.

Petrie turned, and:

“Something I haven’t heard for ten years,” he replied—and I saw with concern that he had grown pale—“which I had hoped never to hear again.”

“What?”

“The signal used by a certain group of fanatics of Burma loosely known as Dacoits.”

“Dacoits? But Dacoity in Burma has been dead for a generation!”

Petrie laughed.

“I made that very statement twelve years ago,” he said. “It was untrue then. It is untrue now. Yet there isn’t a soul in the courtyard.”

And suddenly I realized that he was badly shaken. He was not the type of man who was readily unnerved, and I confess that the incident—trivial though otherwise it might have seemed— impressed me unpleasantly.

“Please God I am mistaken,” he went on, walking back to his chair—“I must have been mistaken.”

But that he was not, suddenly became manifest. The door opened and a woman came in, or rather—ran in.

I had heard men at the club rave about Dr. Petrie’s wife, but the self-chosen seclusion of her life was such that up to this present moment I had never set eyes on her. I realized now that all I had heard was short of the truth. It is fortunate that modern man is unaffected by the Troy complex; for she was, I think, quite the most beautiful woman I had ever seen in my life. I shall not attempt to describe her, for I could only fail. But, seeing that she had not even noticed my existence, I wondered, as men will sometimes wonder, by what mystic chains Dr. Petrie held this unreally lovely creature.

She ran to him and he threw his arms about her.

“You heard it!” she whispered. “You heard it!”

“I know what you are thinking, dear,” he said. “Yes, I heard it. But after all it isn’t possible.”

He looked across, at me, and suddenly his wife seemed to realize my presence.

“This is Mr. Shan Greville,” Petrie went on, “who brings me very sad news about our old friend, Sir Lionel Barton. I didn’t mean you to know, yet. But…”

Mrs. Petrie conquered her fears and came forward to greet me.

“You are very welcome,” she said.

She spoke English with a faint fascinating accent.

“But your news—do you mean—”

Into the beautiful eyes watching me I saw the strangest expression creeping. It was questioning, doubting; fearful, analytical. And suddenly Mrs. Petrie turned from me to her husband, and:

“How did it happen?” she asked.

As she spoke the words, I thought she seemed to be listening.

Briefly, Dr. Petrie repeated what I had told him, concluding by handing his wife the mysterious telegram.

“If I may interrupt for a moment,” I said, taking out my pocket case, “Sir Lionel must have written this at the moment of his fatal seizure. You see—it tails off. It was scribbled on the block which lay beside him. It was what brought me to Cairo.”

I handed the pencilled message to Petrie. His wife bent over him as he read aloud, slowly:

“Not dead… Get Petrie… Cairo… amber… inject…”

She was facing me as he read—her husband could not see her face. But he saw the telegram slip from her fingers to the carpet.

“Kara!” he cried. “My dear! What is it?”

Her wonderful eyes, widely opened, were staring past me through the window out into the courtyard; and:

“He is alive!” she whispered. “O God! He is alive!”

I wondered if she referred to Sir Lionel; when suddenly she turned to Petrie, clutching the lapels of his coat and speaking eagerly, fearfully.

“Surely you understand? You must understand. That cry in the garden and now—this! It is the Living Death! It is the Living Death! He knew before it claimed him. ‘Amber—inject.’” She shook Petrie with a sudden passionate violence. “Think!… The flask is in your safe.”

And, watching Petrie’s face, I realized that what had been unintelligible to me, to him had brought light.

“Merciful heavens!” he cried, and now I saw positive horror leap to his eyes. “Merciful heavens! I can’t believe it—I won’t believe it.”

He stared at me, a man distracted; and:

“Sir Lionel believed it,” his wife said. “He wrote it. This is what he means.”

And now I remembered those hideous oblique eyes which had looked in at me during my journey. I remembered the man in the car who had passed me at Shepheard’s. Dacoits! Bands of Burmese robbers! I had thought of them as scattered. Apparently they were associated—a sort of guild. Sir Lionel knew the Far East almost better than he knew the Near East. So, suddenly I spoke—or rather I cried the words aloud:

“Do you mean, Mrs. Petrie, that you think he’s been murdered?”

Dr. Petrie interrupted, and his reply silenced me.

“It’s worse than that,” he said.

If I had come to Cairo bearing a burden of sorrow, I thought, looking from the face of my host to the beautiful face of his wife, that my story had brought their happy world tumbling about them in dust.

The train to Luxor was full, but I had taken the precaution of booking accommodation before leaving the station. And, as I was later to learn, I had been watched!

I was frankly out of my depth. That Petrie was deeply concerned for his wife, who seemed now to be the victim of a mysterious terror, he was quite unable to conceal. The object locked in the safe referred to by Mrs. Petrie proved to be a glass flask sealed with wax and containing a very small quantity of what might, from its appearance, have been brandy. However, the doctor packed it up with care and placed it in his professional bag before leaving.

This, together with the feverish state of excitement into which I seemed to have thrown his household, was sufficiently mystifying. Coming on top of a tragedy and a sleepless night, it was almost the last straw.

Petrie explored the train as though he expected to find Satan in person on board.

“Are you looking for my cross-eyed man?” I asked.

“I am,” he returned grimly.

And somehow, as his steady glance met mine, it occurred to me that he was hoping, and not fearing, to see the oblique-eyed spy. It dawned upon me that his fears were for his wife, left behind in Cairo, rather than for us. What in heaven’s name was it all about?

However, I was too far gone to pursue these reflections, and long before the attendant had come to make the bed I fell fast asleep.

I was awakened by Dr. Petrie.

“I prescribe dinner,” he said.

Feeling peculiarly cheap, I managed to make myself sufficiently presentable for the dining car, and presently sat down facing my friend, of whom I had heard so much and whom the chief had evidently regarded as a safe harbour in a storm.

A cocktail got me properly awake again and enabled me to define where troubled dreams left off and reality began. Petrie was regarding me with an expression compounded of professional sympathy and personal curiosity; and:

“You have had a desperately trying time, Greville,” he said. “But you can’t have failed to see that you have exploded a bombshell in my household. Now, before I say any more on the latter point, please bring me up to date. If there’s been foul play, is there anyone you could even remotely suspect?”

“There is certainly a lot of mystery about our job,” I confessed. “I know for a fact that Sir Lionel’s rivals—I might safely call them enemies—have been watching him closely—notably Professor Zeitland.”

“Professor Zeitland died in London a fortnight ago.”

“What!”

“You hadn’t heard? We had the news in Cairo. Therefore, he can be ruled out.”

There was a short interval whilst the waiter got busy, and then:

“As I remember poor Barton,” Petrie mused, “he was always surrounded by clouds of strange servants. Are there any in your camp?”

“Not a soul,” I assured him. “We’re a very small party. Sir Lionel, myself, Ali Mahmoud, the headman, Forester, the chemist—I have mentioned him before; and the chief’s niece, Rima; who’s our official photographer.”

I suppose my voice changed when I mentioned Rima; for Petrie stared at me very hard, and:

“Niece?” he said. “Odd jobs women undertake nowadays.”

“Yes,” I answered shortly.

Petrie began to toy with his fish. Clearly his appetite was not good. It was evident that repressed excitement held him—grew greater with every mile of our journey.

“Do you know Superintendent Weymouth?” he asked suddenly.

“I’ve met him at the club,” I replied. “Now that you mention it, I believe Forester knows him well.”

“So do I,” said Petrie, smiling rather oddly. “I’ve been trying to get in touch with him all day.” He paused, then:

“There must be associations,” he went on. “Some of you surely have friends who visit the camp?”

That question magically conjured up a picture before my mind’s eye—the picture of a figure so slender as to merit the description serpentine, tall, languorous; I saw again the brilliant jade-green eyes, voluptuous lips, and those slim ivory hands nurtured in indolence… Madame Ingomar.

“There is one,” I began—I was interrupted.

The train had begun to slow into Wasta, and high above those curious discords of an Arab station, I had clearly detected a cry:

“Dr. Petrie! A message for Dr. Petrie.”

He, too, had heard it. He dropped his knife and fork and his expression registered a sudden consternation.

As Petrie sprang to his feet, a tall figure in flying kit came rushing into the dining car, and:

“Hunter!” Petrie exclaimed. “Hunter!”

I, too, stood up in a state of utter bewilderment.

“What’s the meaning of this?” Petrie went on.

He turned to me, and:

“Captain Jameson Hunter, of Imperial Airways,” he explained— “Mr. Shan Greville.”

He turned again to the pilot.

“What’s the idea, Hunter?” he demanded.

“The idea is,” the airman replied, grinning with evident enjoyment, “that I’ve made a dash from Heliopolis to cut you off at Wasta! Jump to it! You’ve got to be clear of the train in two minutes!”

“But we’re in the middle of dinner!”

“Don’t blame me. It’s Superintendent Weymouth’s doing. He’s standing by where I landed the bus.”

“But,” I interrupted, “where are we going?”

“Same place,” said the airman, grinning delightedly. “But I can get you there in no time, save you the Nile crossing and land you, I believe, within five hundred yards of the camp. Where’s your compartment? You have to run for your things or leave them on the train. It doesn’t matter much.”

“It does,” I said. I turned to Petrie. “I’ll get your bag. Fix things with the attendant and meet me on the platform.”

I rushed out of the dining car, observed in blank astonishment by every other occupant. Our compartment gained, I nearly knocked over the night attendant who was making the bed. Dr. Petrie’s bag I grabbed at once. Coats, hats, and two light suitcases were quickly bundled out. I thrust some loose money into the hand of the badly startled attendant and made for the exit.

Petrie’s bag I managed to place carefully on the platform. The rest of the kit I was compelled to throw out unceremoniously—for the train was already in motion. I jumped off the step and looked along the platform.

Far ahead, where the dining car had halted, I saw Petrie and Jameson Hunter engaged apparently in a heated altercation with the station master. Heads craned through many windows as the Luxor express moved off.

And suddenly, standing there with the baggage distributed about me, I became rigid, staring—staring—at a yellow, leering face which craned from a coach only one removed from that we had occupied.

The spy had been on the train!

I was brought to my senses by a tap on the arm. I turned. An airways mechanic stood at my elbow.

“Mr. Greville,” he said, “is this your baggage?”

I nodded.

“Close shave,” he commented. He began to pick up the bags. “I think I can manage the lot, sir. Captain Hunter will show you the way.”

“Careful with the black bag!” I cried. “Keep it upright, and for heaven’s sake, don’t jolt it!”

“Very good, sir.”

Hatless, dinnerless, and half asleep I stood, until Jameson Hunter, Dr. Petrie, and the station master joined me.

“It’s all settled,” said Hunter, still grinning cheerfully. “The station master here was rather labouring under the impression that it was a hold-up. I think he’s been corrupted by American movies. Well, here we go!”

But the station master was by no means willing to let us go. He was now surrounded by a group of subordinates, and above the chatter of their comments I presently gathered that we must produce our tickets. We did so, and pushed our way through the group. Further official obstruction was offered… when all voices became suddenly silent.

A big man, wearing a blue serge suit, extraordinarily reminiscent of a London policeman in mufti, and who carried his soft hat so that the moonlight silvered his crisp white hair, strolled into the station.

“Weymouth!” cried Petrie. “This is amazing! What does it mean?”

The big, genial man, whom I had met once or twice at the club, appeared to be under a cloud. His geniality was less manifest than usual. But the effect of his arrival made a splendid advertisement for the British tradition in Egypt. The station master and his subordinates positively wilted in the presence of this one-time chief inspector of the Criminal Investigation Department now in supreme command of the Cairo detective service.

Weymouth nodded to me, a gleam of his old cheeriness lighting the blue eyes; then:

“I don’t begin to think what it means, Doctor,” he replied, “but it was what your wife told me.”

“The cry in the courtyard?”

“Yes. And the telegram I found waiting when I got back.”

“Telegram?” Petrie echoed. He turned to me. “Did you send it, Greville?”

“No. Do you mean, Superintendent, you received a telegram from Luxor?”

“I do. I received one today.”

“So did I,” said Petrie, slowly. “Who, in sanity’s name, sent those telegrams, Greville?”

But to that question I could find no answer.

“It’s mysterious, I grant,” said Weymouth. “But whoever he is, he’s a friend. Mrs. Petrie thinks—”

“Yes,” said Petrie, eagerly.

Weymouth smiled in a very sad way, and:

“She always knew in the old days,” he added. “It was uncanny.”

“It was,” Petrie agreed.

“Well, over the phone tonight she told me—”

“Yes?”

“She told me she had the old feeling.”

“Not—?”

“So I understood, Doctor. I didn’t waste another minute. I phoned Heliopolis and by a great stroke of luck found Jameson Hunter there with a bus, commissioned to pick up an American party now in Assouan. He was leaving in the morning, but I arranged with him to leave tonight.”

“Moonlight is bad for landing unless one knows the territory very well,” Jameson Hunter interrupted. “Fortunately I knew of a good spot outside here, and I know another just behind Der-el-Bahari. If we crash, it will be a bad show for Airways.”

We hurried out to where a car waited, Dr. Petrie personally carrying the bag with its precious contents; and soon, to that ceaseless tooting which characterizes Egyptian drivers, we were dashing through the narrow streets with pedestrians leaping like hares from right and left of our course.

Outside the town we ran into a cultivated area, but only quite a narrow belt. Here there was a road of sorts. We soon left this and were bumping and swaying over virgin, untamed desert. On we went, and on, in the bright moonlight. I seemed to have stepped over the borderline of reality. The glorious blaze of stars above me had become unreal, unfamiliar. My companions were unreal—a dream company.

All were silent except Jameson Hunter, whose constant ejaculations of “Jumping Jupiter!” when we took an unusually bad bump indicated that he at least had not succumbed to that sense of mystery which had claimed the rest of us.

On a long, gentle slope dangerously terminated by a ravine, the plane rested. Our baggage was quickly transferred from the car and we climbed on board. A second before the roar of the propeller washed out conversation:

“Hunter,” said Weymouth, “stretch her to the full. It’s a race to save a man from living death…”

CHAPTER TWO

Rima

It was bumpy traveling and I had never been a good sailor. Jameson Hunter stuck pretty closely to the river but saved miles, of course, on the many long bends, notably on that big sweep immediately below Luxor, where, leaving the Nile Valley north of Farshût, we crossed fifty miles of practically arid desert, heading east-southeast for Kûrna.

I was in poor condition, what with lack of sleep and lack of meals; and I will not enlarge upon my state of discomfort beyond saying that I felt utterly wretched. Sometimes I dozed; and then Rima’s grave eyes would seem to be watching me in that maddeningly doubtful way. Once I dreamed that the slender ivory hands of Madame Ingomar beckoned to me…

I awoke in a cold perspiration. Above the roar of the propeller I seemed to hear her bell-like, hypnotic voice…

Who was this shadowy figure, feared by Petrie, by his wife—by Weymouth? What had he to do with the chief’s sudden death? Were these people deliberately mystifying me, or were they afraid to tell me what they suspected?

Forester was convinced that Barton was dead. I could not doubt it. But in the incomprehensible message scribbled at the last, Petrie seemed to have discovered a hope which was not apparent to me. Weymouth’s words had reinforced it.

“A race to save a man from living death.”

Evidently he too, believed… believed what?

It was no sort of problem for one in my condition, but at least I had done my job quicker than I could have hoped. Luck had been with me.

Above all, my own personal experience proved that there was something in it. Who had sent the telegrams? Who had uttered that cry in the courtyard? And why had I been followed to Cairo and followed back? Thank heaven, at last I had shaken off that leering, oblique-eyed spy.

Jameson Hunter searched for and eventually found the landing place which he had in mind—a flat, red-gray stretch east of the old caravan road.

I was past reliable observation, but personally I could see nothing of the camp. This perhaps was not surprising as it nestled at the head of a wâdi, represented from our present elevation by an irregular black streak.

However, I was capable of appreciating that the selected spot could not be more than half a mile west of it. Hunter brought off a perfect landing, and with a swimming head I found myself tottering to the door.

When I had scrambled down:

“Wait a minute,” said Petrie. “Ah, here’s my bag. You’ve been through a stiff time, Greville. I am going to prescribe.”

His prescription was a shot of brandy. It did me a power of good.

“If we had known,” said Hunter; “some sandwiches would have been a worthy effort. But the whole thing was so rushed—I hadn’t time to think.”

He grinned cheerfully.

“Sorry my Phantom-Rolls isn’t here to meet us,” he said. “Someone must have mislaid it. It’s a case of hoofing, but the going’s good.”

Carrying our baggage, we set out in the moonlight. We had all fallen silent now, even Jameson Hunter. Only our crunching footsteps broke the stillness. I think there is no place in the world so calculated to impress the spirit of man as this small piece of territory surrounding those two valleys where the quiet dead of Egypt lie. At night, when the moon sails full, he would be a pitiful soul who, passing that way, failed to feel the touch of eternity.

For my own part, as familiar landmarks appeared, a dreadful unrest compounded of sorrow and hope began to take possession of me. Above all, selfishly no doubt, I asked myself again and again— had Rima returned?

We were not expected until morning when the Cairo train arrived. Consequently I was astounded when on mounting the last ridge west of the wâdi I saw Forester hurrying to meet us. Of course, I might have known, had I been capable of associating two ideas, that the sound of our approach must have aroused the camp.

Forester began to run.

Bad news casts a long shadow before it. I forgot my nausea, my weariness. It came to me like a revelation that something fresh had occurred—something even worse than that of which I had carried news to Cairo.

I was not alone in my premonition. I saw Weymouth grasp Petrie’s arm.

Forester began shouting:

“Is that you, Greville? Thank God you’ve come!”

Now, breathless, he joined us.

“What is it?” I asked. “What else has happened?”

“Only this, old man,” he panted. “We locked the chief’s body in the big hut, as you remember. I had serious doubts about notifying the authorities. And tonight about dusk I went to… look at him.”

He grasped me by both shoulders.

“Greville!” Even in the moonlight I could see the wildness in his eyes. “His body had vanished.”

“What!” Weymouth yelled.

“There isn’t a trace—there isn’t a clue. He’s just been spirited away!”

“If only Nayland Smith could join us,” said Weymouth.

Dr. Petrie, looking very haggard in the lamplight, stared at him.

“The same thought had just crossed my own mind,” he replied. “I am due to sail for England on Thursday. I had been counting the days. He’s meeting me in…”